Abstract

PACAP is a critical regulator of long-term catecholamine secretion from the adrenal medulla in vivo, however the receptor or pathways for Ca2+ entry triggering acute and sustained secretion have not been adequately characterized. We have previously cloned the bovine adrenal chromaffin cell PAC1 receptor that contains the molecular determinants required for PACAP-induced Ca2+ elevation and is responsible for imparting extracellular Ca2+ influx-dependent secretory competence in PC12 cells. Here, we use this cell model to gain mechanistic insights into PAC1hop-dependent Ca2+ pathways responsible for catecholamine secretion. PACAP-modulated extracellular Ca2+ entry in PC12 cells could be partially blocked with nimodipine, an inhibitor of L-type VGCCs and partially blocked by 2-APB, an inhibitor and modulator of various transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. Despite the co-existence of these two modes of Ca2+ entry, sustained catecholamine secretion in PC12 cells was exclusively modulated by 2-APB-sensitive calcium channels. While IP3 generation occurred after PACAP exposure, most PACAP-induced Ca2+ mobilization involved release from ryanodine-gated cytosolic stores. 2-APB sensitive Ca2+ influx, and subsequent catecholamine secretion was however not functionally related to intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and store depletion. The reconstituted PAC1hop-expessing PC12 cell model therefore recapitulates both PACAP-induced Ca2+ release from ER stores and extracellular Ca2+ entry that restores PACAP-induced secretory competence in neuroendocrine cells. We demonstrate here that although bPAC1hop receptor occupancy induces Ca2+ entry through two independent sources, VGCCs and 2-APB sensitive channels, only the latter contributes importantly to sustained vesicular catecholamine release that is a fundamental characteristic of this neuropeptide system. These results emphasize the importance of establishing functional linkages between Ca2+ signaling pathways initiated by pleotrophic signaling molecules such as PACAP, and physiologically important downstream events, such as secretion, triggered by them.

Keywords: PACAP, Calcium, Secretion, Chromaffin, PC12, 2-APB

1. Introduction

Since the discovery and cloning of the six major splice variants of the pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) type -1 receptors (PAC1) [1,2] significant progress has been made in understanding the signal transduction mechanisms of these G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) in relation to Ca2+ signaling. Elucidating the receptor-specific mechanisms of PACAPs action are of particular importance because PACAP participates in both acute and sustained effects at various synapses, and these are likely to have differential effects on regulation of homeostasis in vivo. Therefore acute catecholamine release from chromaffin cells in vivo [3-5] and in culture evoked by either acetylcholine or PACAP occurs within a few seconds-minutes, via a mechanism that requires calcium influx through voltage-dependent calcium channels [6-11]. This mechanism most likely underlies acute responses, such as the flight-or-fight reflex mediated at the adrenomedullary synapse from the so-called primed readily releasable pool (RRP) of vesicles in chromaffin cells [12-14]. A second and longer phase of PACAP-dependent secretion occurs within several minutes to hours, and may involve secretion from a second, RRP-independent releasable pool of vesicles in chromaffin cells [14] that is mechanistically controlled though voltage-independent calcium channels [9]. This second, sustained phase of catecholamine secretion is of great importance physiologically, as it is this phase of secretion that is presumably responsible for survival during prolonged hypoglycemia [15] and for the long-term, PACAP-dependent adrenomedullary catecholamine response to psychogenic stressors [16].

In addition to PACAP-evoked extracellular Ca2+ influx, PACAP modulates Ca2+ release from intracellular endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stores [1,6,7,15. Early characterization studies of the PAC1 receptor variants potentially responsible for evoking PACAP-dependent Ca2+ signaling suggested that the PAC1hop and PAC1null, but not the PAC1hip variant of this receptor, were coupled to both adenylate cyclase activation through Gs, and activation of phospholipase C presumably through Gq. This assumption was based on the ability of PACAP to increase total inositol phosphate accumulation in heterelogous cells lines expressing the receptor variants, which in turn predicted regulation of Ca2+ release from InsP3R-sensitive ER stores by PACAP [2]. Tanaka and colleagues additionally revealed using real-time fluorometric monitoring of cytosolic Ca2+, the ability of PACAP to regulate Ca2+ release mainly from ryanodine receptorgated intracellular Ca2+ stores [7] despite simultaneous generation of inositol phosphates in adrenal chromaffin cells [17].

The complexity of PACAP-mediated Ca2+ signaling has been an obstacle to understanding how PACAP- mediated Ca2+ entry and subsequent stimulation of secretion through its various receptors actually occurs in vivo. Despite earlier reports of a specific PAC1 isoform mediating calcium influx distinct from the PAC1hop isoform found in chromaffin cells [18], we have since demonstrated that the PAC1hop isoform alone can support calcium influx when transfected into a PC12 cell line that is otherwise not competent for sustained PACAP secretion [11].

In this study we employed this cell line, PC12+bPAC1hop, to study reconstituted PACAP-mediated intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and extracellular Ca2+ influx to study the functional links among these various modes of intracellular calcium elevation, and their role in mediating sustained catecholamine secretion. We demonstrate for the first time the ability of PACAP to trigger extracellular Ca2+ influx through 2-APB-sensitive, Ca2+ channels, and that this mode of calcium entry is responsible for sustained catecholamine secretion mediated through the PAC1hop receptor, the major form of PAC1 expressed in chromaffin cells, sympathetic neurons, and in the central nervous system.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

PACAP-38 was purchased from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (Mountain View, CA). 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), U-73122, U-73343, ryanodine and ET-18-OCH3 (Edelfosine), were obtained from Calbiochem-EMD Biosciences. ω-Conotoxin MVIIC, ω-Conotoxin GVIA, nimodipine, mibefradil dihydrochloride hydrate, ATP and cinnarizine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All tissue culture reagents were obtained from Invitrogen unless specified otherwise.

2.2. Cell Culture

PC12-G rat pheochromocytoma cells [19] were cultured in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 7.5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Hyclone, UT), 7.5% horse serum (Bio-Whittaker-Cambrex, MD), 25 mM HEPES, 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin and 2 mM glutamine. PC12-G cells stably expressing the bPAC1hop receptor (PC12+bPAC1hop) were created as previously described [11]. Briefly, lipofectamine2000™ (Invitrogen, CA) was used to transfect PC12-G cells with the bovine PAC1 receptor (bPAC1hop) and stably transfected cells were selected and maintained in media supplemented with 500 μg/ml G418. All cells were used between passages 6 and 25.

2.3. Measurement of single cell [Ca2+]i

Measurement of [Ca2+]i in PC12 cells was performed by monitoring fura-2 fluorescence as previously described. Briefly, 400,000 PC12-G or PC12+bPAC1hop cells were seeded onto 1.5 cm diameter glass coverslip slides (Assistent, Germany) coated with 0.5 mg/ml poly-L-lysine 24h prior to imaging. Fura-2 loading was carried out by incubating cells with 4 μM Fura-2-AM (Invitrogen, Molecular Probes, OR) in Krebs-Ringer buffer (KRB) containing (in mM) 125 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 Na2HPO4, 1 MgSO4, 1 CaCl2, 5.5 glucose and 20 HEPES, pH 7.3 for 22 min at room temperature followed by a further 22 min wash in Fura-2-free KRB prior to imaging. Cells on coverslips mounted onto a custom built perfusion chamber were alternatively excited at 340 nm and 380 nm, and emitted light was collected at 510 nm every 2 sec. The ratiometric fluorescence of Fura-2 served as a measure of [Ca2+]i as previously described [11]. All experiments were conducted following a standard experimental paradigm, as follows. Cells were perfused with KRB for 60 sec to establish a stable baseline, and then with KRB containing PACAP or other secretagogues at the specified concentrations followed by a final 60 sec KRB wash unless specified otherwise. Pharmacological inhibitors were administered 30 min prior to secretagogue treatment and included in all subsequent washes and treatments at the specified concentrations. Ca2+−free experiments were conducted utilizing Ca2+ free KRB buffer supplemented with 100 μM EGTA. The collected data were obtained as averages from 3-15 experiments, each comprising 2-3 slides from which approximately 30 cells were selected for individual [Ca2+]i measurements.

2.4. Total Inositol Phosphate Measurements

Labeling and detection of total inositol phosphates in PC12 cells was based on a previously described procedure [20] with the following modifications. Briefly PC12-G cells or PC12+bPAC1hop cells were plated at a density of 180,000 cells/well in 0.1 mg/ml poly-L-lysinecoated 24 well plates and allowed to adhere overnight. Inositol phospholipids were labeled by incubating cells in the presence of 1 μCi myo-[3H]-inositol (30 Ci/mmol) (Amersham) in complete culture media for 24h. Unincorporated radioactivity was then removed by washing cells with KRB containing 0.1% BSA supplemented with 20 mM LiCl2, to prevent metabolism of newly formed inositols, then pre-incubated for an additional 30 min at 37° C in the same buffer prior to agonist stimuation for 60 minutes at 37°C. Treatments were terminated and cells lysed by incubation in ice-cold KRB containing 6% perchloric acid and 20 mM LiCl2 for 60 min under constant agitation at 4°C. The cell lysates were then neutralized with a pre-determined volume of 1 N KOH and 20 mM HEPES and the 3H-labelled inositols in the aqueous phase were extracted with an equal volume of pre-prepared Dowex AG 1X1- 8 (100-200 formate form) resin (Bio-Rad). Total inositol phosphates eluted from the resin with 1.2 M ammonium formate and 0.1 M formic acid solution were then counted in a liquid scintillation counter. Values are the ±S.E.M of triplicate wells performed over at least 3 independent experiments. The statistical difference between control and treatment groups was determined using T-test using the GRAPHPAD PRISM program (GraphPad Software 4.0).

2.5. [3-H]-Norepinephrine uptake and release studies

The uptake and release of [3H]-norepinephrine in PC12-G or PC12+PAC1hop cells was carried out as previously described [11]. Cells loaded with 1 μCi/well of Levo-[7-3H]-norepinephrine (1 mCi/ml, Perkin Elmer, USA) for 4h in complete media at 37°C were washed with PBS and pre-incubated for 30 min at 37°C in the presence or absence of pharmacological inhibitors or vehicle in KRB prior to addition of 100 nM PACAP-38 or 55 mM KCl. Following stimulation for 30 min at 37°C the level of radioactivity in secretion buffer and cell lysates was determined by liquid scintillation counting and analyzed as previously described [11]. The statistical difference between control and treatment groups was determined using one-way analysis of variance by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests using the GRAPHPAD PRISM program (GraphPad Software 4.0).

3. Results

3.1. Reconstitution of PACAP-induced Ca2+ elevation and catecholamine secretion in bPAC1hop-expressing PC12 cells

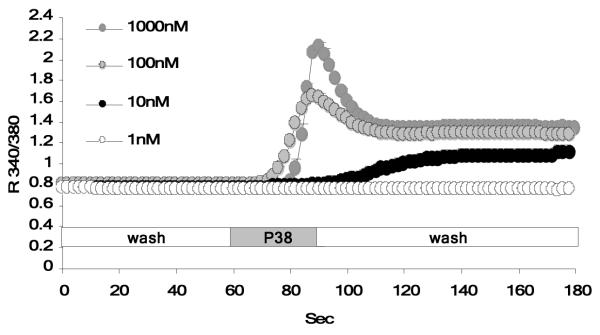

As previously reported, wild type PC12 cells display a small but distinct elevation in intracellular Ca2+ after exposure to PACAP. Stable expression of PAC1hop in PC12 cells, at similar levels to PAC1hop expression in BCCs, results in the acquisition of a significant PACAP-evoked Ca2+ response. The PACAP-evoked Ca2+ response measured in these cells can be dissociated into two main components (Figure 1): an initial rapid peak that transitions into a lower magnitude plateau phase, that is maintained well after removal/wash-out of PACAP. Exposure of PC12+bPAC1hop cells to 100 nM PACAP, was sufficient to stimulate maximal PAC1hop receptor-mediated calcium transients. A lower dose of PACAP (10 nM) resulted in suboptimal Ca2+ transients (Figure 1), while a higher supramaximal dose (1000 nM) did not further increase Ca2+ levels in PC12+bPAC1hop cells. This confirms that 100 nM of PACAP, used in our current and previous studies, results in maximal Ca2+ stimulation required for functional catecholamine secretion in PC12 cells.

Figure 1. Expression of the bPAC1hop receptor in PC12 cells facilitates PACAP-evoked Ca2+ transients.

Exposure of PC12+bPAC1hop cells to increasing concentrations of PACAP evokes Ca2+ elevation that occurs in two distinct phase; an initial rapid peak that transitions into a lower magnitude sustained plateau phase. Treatment of cells with 100 nM PACAP, resulted in optimal Ca2+ transients, with a lower, 10 nM dose of PACAP failing to significantly induced Ca2+ transients while higher doses did not further increase PACAP-evoked Ca2+ transients in PC12+bPAC1hop cells.

3.2. PACAP-evoked Ca2+ influx occurs partially through dihydropyridine-sensitive, L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) but is not a major component of sustained catecholamine secretion

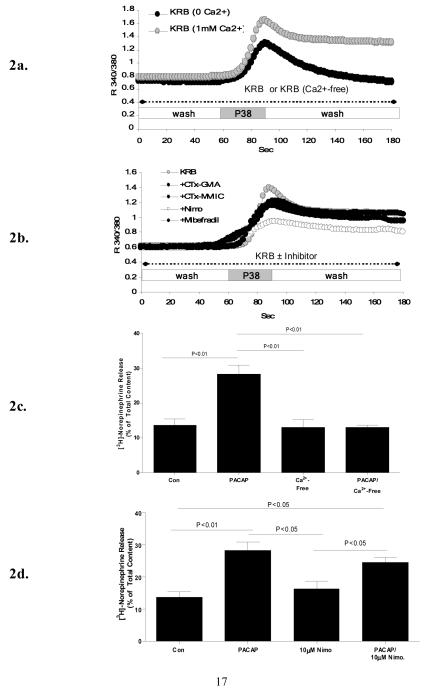

As we have previously reported and reconfirmed in the current studies, exposure of PC12+bPAC1hop cells to 100 nM PACAP-38 in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, indicates that the first phase of PACAP-induced Ca2+ elevation involves release of Ca2+ from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stores and the later sustained phase occurs via extracellular Ca2+ influx (Figure 2a) that is essential in reconstituting secretory competence in these neuroendocrine cells (Figure 2c). Secretion in PC12 cells was monitored via release of previously accumulated 3H-norepinephrine over a period of 30 minutes, to over come the smaller RRP size described in PC12 versus bovine chromaffin cells [21]. Our previous studies characterizing PACAP-evoked Ca2+ signaling in bovine chromaffin cells in primary culture demonstrate inhibition of PACAP-evoked Ca2+ influx by the general cation influx inhibitor D600, but only partially by the L-type calcium channel inhibitor nimodipine, with acute [11,15], but not prolonged secretion inhibited by L-type calcium channel blockade [22]. To assess whether similar mechanisms are utilized in PC12 cells, PACAP-evoked Ca2+ mobilization was monitored in the presence of pharmacological inhibitors of VGCCs. Pretreatment of PC12+bPAC1hop cells with 10 μM nimodipine, prior and during PACAP treatment, also only partially blocked PACAP-stimulated Ca2+ influx (Figure 2b). The same concentration of nimodipine completely blocked Ca2+ influx driven by 55 mM KCl depolarization in PC12+bPAC1hop cells (results not shown). The remaining dihydropyridine-insensitive Ca2+ influx was not sensitive to blockade of N-type (1 μM ω-CTx GV1A), P/Q-type (1 μMω-CTx MVIIC) and T-type (30 μM mibefradil) VGCCs (Figure 2b). In parallel studies, pre-treatment of cells with 10 μM nimodipine for 30 minutes prior to and during PACAP-stimulation, only had a partial inhibitory effect on PACAP-evoked catecholamine secretion (Figure 2d), indicating that PACAP-evoked Ca2+ influx through L-type VGCCs does not support sustained catecholamine secretion in PC12+bPAC1hop cells.

Figure 2. PACAP modulates Ca2+ influx through L-type VGCCs but does not utilize this source of Ca2+ to drive secretion in PC12+bPAC1hop cells.

In the absence of extracellular Ca2+, PACAP-induced Ca2+ elevation is transient and rapidly returns to resting levels to demonstrate that PACAP-evokes both intracellular and extracellular Ca2+ mobilization (a). PACAP-evoked extracellular Ca2+ influx was partially blocked by the L-type VGCC channel inhibitor Nimodipine (10 μM) which could not be further attenuated by blocking N-type (1 μM ω-CTx GV1A), P/Q-type (1 μMω-CTx MVIIC) and T-type (30 μM mibefradil) VGCCs (b). This source of bPAC1hop receptor reconstituted extracellular Ca2+ influx is an essential requirement of PACAP-evoked catecholamine release in PC12 cells (c) however treatment of PC12+bPAC1hop cells with 10 μM nimodipine for 30 minutes prior and during PACAP-stimulation failed to block PACAP-evoked catecholamine release suggesting that PACAP-modulated Ca2+ current through L-type VGCCs does not drive sustained secretion in PC12 cells (d).

3.3. PACAP stimulation of total inositol phosphate production in bPAC1hop expressing PC12 cells

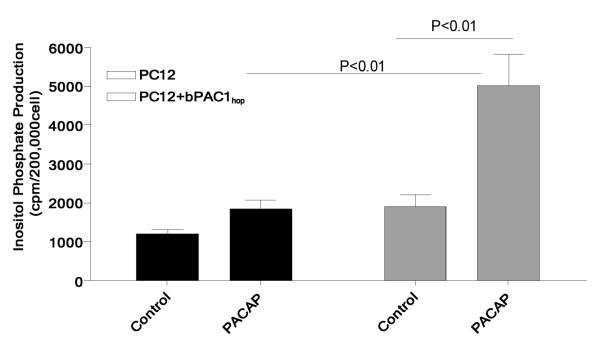

To examine the possible mechanism and source of PACAP-induced intracellular cytosolic Ca2+ in PC12 cells, the ability of PACAP to stimulate inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (InP3) generation was determined in PC12 and PC12+bPAC1hop cells. Cells were treated with 100 nM PACAP and total inositol phosphate production was measured. 100 nM PACAP failed to stimulate the production of total inositol phosphates in PC12 cells pre-loaded with myo-[3H]-inositol (Figure 3), while expression of the bPAC1hop receptor in PC12 cells resulted in a significant increase in the number of total labeled inositols after exposure to 100 nM PACAP (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Expression of the bPAC1hop receptor in PC12 cells induces PACAP-mediated inositol phosphate production.

Stimulation of PC12+bPAC1hop cells with an equivalent dose of 100 nM PACAP shown to cause large Ca2+ transients in PC12 cells resulted in a significant production of total inositol phosphates that was not observed in control PC12 cells or nonstimulated PC12+bPAC1hop cells.

3.4. Relationship between PACAP-evoked IP3 generation and Ca2+ release from cytosolic stores

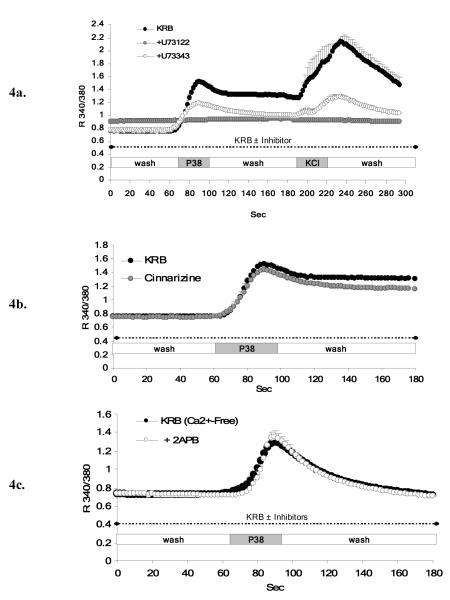

Stimulation of PC12+bPAC1hop cells with PACAP in the presence of 10 μM U73122, an inhibitor of PLC, completely blocked PACAP-induced Ca2+ elevations in PC12 cells (Figure 4a). However, the same concentration of U73122 also inhibited K+-induced depolarization indicating non-specific (non PLC-related) actions of U73122. As shown in Figure 4a, 10 μM U73343, an inactive analogue that does not inhibit PLC, also attenuated both PACAP- and K+-induced Ca2+ elevation in PC12 cells, albeit less than U73122, suggesting PLC-independent effects of the two structurally related compounds in PC12 cells. A second PLC-inhibitor, edelfosine (ET-18-OCH3) could not be used to evaluate PLC-IP3 receptor mediated Ca2+ release in PC12 cells, due to short-term toxicity at the doses reported to be effective for PLC inhibition (unpublished personal observation).

Figure 4. Characterization of PACAP-evoked Ca2+ release from IP3 receptor gated-intracellular Ca2+ stores in PC12+bPAC1hop cells.

To establish whether PACAP-induced intracellular Ca2+ release occurs through PLC-InsP3-senistive cytoplasmic stores, PC12+bPAC1hop cells where pre-incubated with the PLC inhibitor U73122 (10 μM) prior and during PACAP-treatment. U73122 completely abolished PACAP-evoked intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and influx (a), however the same dose of U73122 also blocked 55 mM KCl-mediated depolarization that occurs totally independent of intracellular stores in PC12 cells (a). The non-specific actions of U73122 was confirmed by the ability of the structurally related control peptide, U73343, that does not block PLC, to also attenuate PACAP and KCl stimulated Ca2+ transients in PC12 cells. We next employed cinnarizine, a reported inhibitor of the IP3 receptor, that is activated subsequent to PLC-mediated InsP3 generation. Treatment of PC12+bPAC1hop cells with 30 μM cinnarizine, prior and during PACAP treatment, failed to attenuate the initial transient rise in intracellular Ca2+ while very slightly reducing the amplitude of the plateau phase attributed to PACAP-evoked extracellular influx (b). Application of reported IP3 receptor antagonist, 2-APB (10 μM), in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, to isolate only intracellular Ca2+ mobilization, also failed to block PACAP-induced release of cytosolic Ca2+ (c).

Since known PLC inhibitors could not reliably be used in PC12 cells to assess the role of Gq-PLC-IP3-mediated pathways for Ca2+ mobilization, we examined the effect of blocking the InsP3 receptor itself, downstream of PLC activation, on Ca2+ mobilization. Treatment of PC12+bPAC1hop cells with 30 μM cinnarizine, an IP3 receptor antagonist, failed to reduce the initial transient rise in PACAP-evoked Ca2+, attributed to release from intracellular stores. Cinnarizine slightly reduced the magnitude of the plateau phase, consistent with the reported ability of cinnarizine to partially block Ca2+ conductance through various VGCCs [23] (Figure 4b). Treatment of PC12+bPAC1hop cells with 10 μM 2-APB, a cell permeable IP3 receptor antagonist, in Ca2+-free KRB, failed to block PACAP-induced calcium mobilization in calcium-free medium (Figure 4c). This concentration of 2-APB was active to block IP3-mediated calcium release in PC12 cells, since it completely blocked ATP-dependent calcium mobilization in these cells (data not shown).

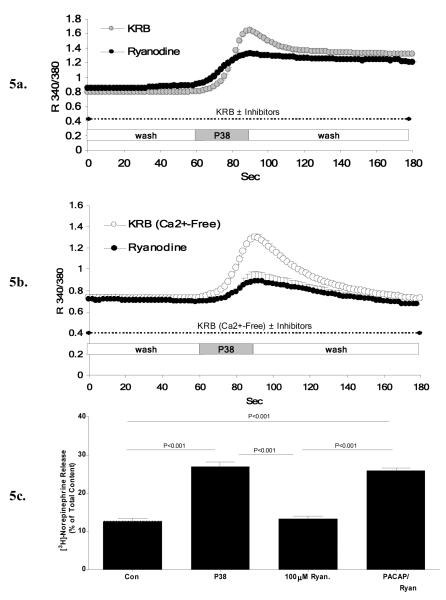

3.5. Inhibition of PACAP-induced, Ca2+ release from ryanodine-gated intracellular stores and PACAP-induced catecholamine secretion in bPAC1hop expressing PC12 cells

To test the ability of PACAP to release intracellular Ca2+ through activation of the ryanodine receptor as previously reported in chromaffin cells [7,17], PC12 cells were pre-incubated for at least 30 minutes with 100 μM ryanodine, a concentration known to reduce the open probability of the ryanodine receptor, prior to and during PACAP-induced Ca2+ measurements. In the presence of extracellular Ca2+, ryanodine prevented the initial transient rise in PACAP-evoked Ca2+ release without changing the plateau phase that is driven by extracellular Ca2+ influx (Figure 5a). The ability of ryanodine to block PACAP-stimulated release of Ca2+ from ER stores was confirmed by removing extracellular Ca2+ to exclude influx, revealing the ability of ryanodine to block a major portion of PACAP-induced Ca2+ elevation in PC12+bPAC1hop cells (Figure 5b). As demonstrated in Figure 5c, similar experimental conditions using 100 μM of ryanodine prior to and during PACAP-exposure did not block PACAP-evoked catecholamine release in PC12 cells, suggesting that ryanodine-receptor mediated depletion of cytoplasmic stores does not appear to be functionally related to PACAP-induced calcium influx responsible for catecholamine secretion in PC12+bPAC1hop cells.

Figure 5. PACAP-evoked Ca2+ release from ryanodine receptor gated-intracellular Ca2+ stores is not related to PACAP-evoked sustained secretion in PC12+bPAC1hop cells.

To test the ability of PACAP to regulate the release of intracellular Ca2+ through activation of ryanodine-gated stores as previously reported, PC12-bPAC1hop cells were pre-incubated with high levels of ryanodine (100 μM) known to reduce the open probability of the ryanodine receptor. The presence of 100 μM ryanodine blocked the initial transient rise in Ca2+ following PACAP-exposure without affecting the overall amplitude of the proceeding plateau phase attributed to Ca2+ influx (a). This finding was confirmed in studies carried out in the absence of intracellular Ca2+ to isolate only intracellular Ca2+ release. Under these conditions, ryanodine significantly blocked PACAP-induced Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (b). PACAP-evoked catecholamine release in PC12+bPAC1hop cells in the presence of 100 μM ryanodine, under identical conditions described above, failed to block PACAP-induced sustained catecholamine secretion.

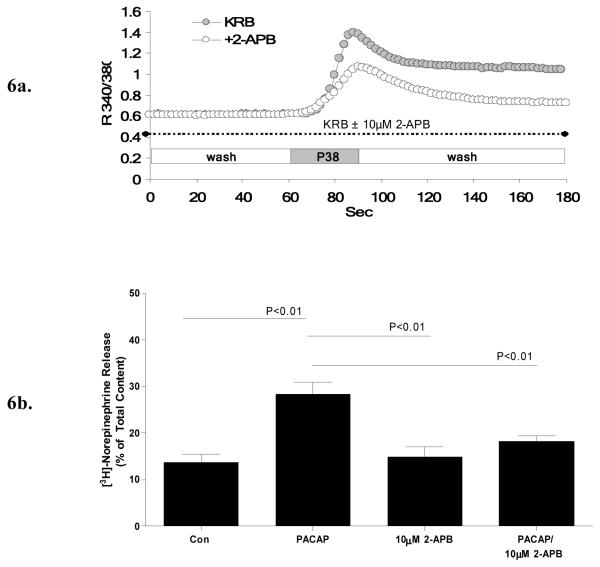

3.6. 2-APB inhibits both PACAP-induced Ca2+ influx and PACAP-evoked catecholamine release

Employing 2-APB as a pharmacological tool to investigate PACAP–induced Ca2+ mobilization from IP3-receptor gated ER stores also provided key insights into the nature of the second source of PACAP-mediated Ca2+ influx. Pre-treatment of PC12+bPAC1hop cells with 2-APB (10 μM), prior to and during PACAP-treatment in KRB containing Ca2+, reduced the magnitude of the plateau phase, attributed to PACAP-evoked Ca2+ influx, to near resting levels in PC12+bPAC1hop cells without affecting the initial transient rise in Ca2+ (Figure 6a). Application of this same concentration of 2-APB, to PC12+bPAChop cells after establishment of the PACAP-evoked Ca2+ influx (plateau phase), also inhibited Ca2+ conductance across the plasma membrane, confirming direct actions of the inhibitor on Ca2+ channels in the open conformation (results not shown). Pre-treatment of cells for 30 minutes with 10 μM 2-APB prior and during PACAP-exposure also completely blocked PACAP-evoked norepinephrine secretion (Figure 6b). Therefore, PACAP acting on the bPAC1hop receptor in PC12 cells triggers Ca2+ influx through 2-APB-sensitive channels, as well as VGCCs, but selectively utilizes the 2-APB-sensitive channels to drive sustained catecholamine secretion.

Figure 6. 2-APB, an inhibitor of SOCE, blocks both PACAP-evoked Ca2+ influx and PACAP-stimulated catecholamine release in PC12+bPAC1hop cells.

Treatment of PC12+bPAC1hop cells with 10 μM 2-APB, prior and during PACAP-treatment, reduced the amplitude of the PACAP induced plateau phase to near resting levels without effecting the initial transient rise attributed to intracellular Ca2+ release (a). PACAP-evoked norepinephrine secretion in PC12+bPAC1hop cells was also modulated through 2-APB sensitive Ca2+ entry as indicated by the ability of 10 μM 2-APB to block PACAP-evoked catecholamine secretion in PC12 cells (b).

4. Discussion

The ability of PACAP to mediate its biological actions is largely dependent on its ability to transduce cAMP and Ca2+ signals through its cognate G-protein coupled receptor, PAC1hop. Coupling to cAMP generation has been demonstrated for all major PAC1 receptor isoforms, while PACAP-induced Ca2+ influx has been convincingly demonstrated so far to be a property of the PAC1hop receptor, at least for the bovine isoform [11]. Using a cell line, PC12+bPAC1hop, expressing the bovine PAC1hop receptor at levels similar to those expressed in bovine chromaffin cells [11] we have shown that PACAP acting through bPAC1hop mediates a biphasic Ca2+ response consisting of an initial steep rise due to release from intracellular Ca2+ stores, followed by a second lower magnitude, long-lasting phase due to extracellular Ca2+ influx. The ability of PACAP to cause Ca2+ influx coupled to catecholamine and secretory protein/peptide release from large dense core vesicles (LDCVs) and calcium- and cAMP-dependent gene transcription, is a unique feature of this peptide’s signaling properties that allows adaptation during both psychogenic and metabolic stress [16]. In fact, calcium-dependent secretion triggered by PACAP can be further distinguished as occurring in a first acute phase, which is blocked largely by L-type VGCCs or mixture of L-, P/Q- and N-type VGCCs channel inhibitors [8,9] and a second sustained phase, which is insensitive to blockage of VGCCs [9]. This two-phase secretion has been demonstrated in bovine chromaffin cells, where the first phase may last up to one hour and the second for several hours or more [11,22] and in a PC12 cell line that is already PACAP-secretion competent without augmented expression of PAC1hop, in which the first phase lasts several minutes and the second two hours or more [9,24]. Our data shows that although PACAP modulates multiple calcium channels as well as calcium mobilization via the PAC1hop receptor in neuroendocrine cells, the sustained phase of secretion from large dense-core vesicles is coupled to calcium influx through 2-APB-sensitive channels, and that opening of these channels by PACAP is triggered directly, rather than by emptying of intracellular calcium stores.

It is of particular interest that although roughly half of the calcium influx triggered by PACAP is blocked by nimodipine, blockade of L-type calcium channels does not have a correspondingly large effect on PACAP-evoked secretion over a thirty-minute period, although some diminution of secretion is apparent. These findings emphasize that activation of secretion is not correlated with net Ca2+ influx over time, but rather may be associated with different modes of extracellular Ca2+ influx during different phases of secretion. This in turn implies that the PACAP-modulated, 2-APB-sensitive Ca2+ influx in PC12 cells may be in correct spatial proximity to vesicles from which sustained catecholamine release occurs in PC12+bPAC1hop cells, while other modes of calcium entry, such as via T-channel activation, may be critical for more acute catecholamine release [25]. We have previously shown that chronic secretion of met-enkephalin from bovine chromaffin cells is dependent on VGCCs when release is triggered by cell depolarization with potassium, but not when chronic release is triggered by PACAP-27 [22]. However, acute secretion of met-enkephalin from BCCs is at least partially sensitive to L-type calcium channel blockade [11]. These results are consistent with our previous findings that PACAP-evoked calcium influx in bovine chromaffin cells is only partially blocked by total blockade of L-type calcium channels, and completely blocked with the non-VGCC-specific calcium channel blocker methoxyverapamil [26]. Using PC12+bPAC1hop cells, in which the dynamics of calcium elevation can be monitored more conveniently than in bovine chromaffin cells with the single-cell monitoring techniques employed here, we have identified the distinct pharmacological specificity of these channels as sensitive to 2-APB, and revealed the contributions of these channels to overall calcium influx, representing about half of calcium influx stimulated by PACAP, and to sustained catecholamine release, all of which appears to require this class of plasma membrane calcium channels.

In addition to modulating two distinct modes of Ca2+ influx in PC12 cells, PACAP also clearly evoked Ca2+ release from intracellular cytosolic stores. The bulk of this release occurs from ryanodine-gated stores [7] despite simultaneous IP3 generation, as previously reported in bovine chromaffin cells [17]. Although initial PACAP-evoked release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores proceeded by 2-APB sensitive influx mechanistically points towards capacitative or store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCEs), we found that PACAP-dependent Ca2+ influx was not proportionally inhibited with high doses of ryanodine shown to block PACAP-stimulated intracellular Ca2+ release. Parallel norepinephrine secretion studies carried out under identical conditions also failed to block PACAP –evoked catecholamine secretion suggesting that PACAP-evoked Ca2+ entry through 2-APB-sensitive Ca2+ channels is not functionally linked, or at least proportionally correlated with Ca2+ release from ryanodine-gated intracellular cytosolic stores in PC12 cells responsible for mediating secretion.

2-APB is commonly described as a membrane-permeable chemical inhibitor of calcium influx through non-selective cation channels that can be activated secondary to Gq-PLC-IP3-mediated ER Ca2+ depletion. This inhibition has been postulated to occur at two levels: inhibition of InsP3-receptor induced emptying of ER Ca2+ stores which can trigger these non-selective cation channels (hence ‘store-operated’ channels), or direct inhibition of Ca2+ entry through the plasma membrane Ca2+ channels themselves, independently of whether Ca2+ influx is triggered by store emptying or by some other mechanisms [27,28]). 2-APB can indeed block ATP-dependent calcium mobilization in PC12+bPAC1hop cells, presumably via inhibition of IP3-mediated Ca2+ store emptying. In the case of PACAP-dependent Ca2+ influx, 2-APB is a direct inhibitor of PACAP-induced Ca2+ entry, and this inhibition is independent of IP3- or ryanodine receptor-mediated cytosolic store depletion.

The identity of the 2-APB-sensitive Ca2+ channel modulated by PACAP in PC12 cells, and presumably also in chromaffin cells, is presently unknown. However, Birnbaumer and colleagues have documented the ability of 2-APB to block store-independent Ca2+ influx in HEK293T cells overexpressing TRPC3, TRPC6 and TRPC7 family members that could be suggestive of the type of Ca2+ channels regulated by PACAP [28]. Many studies characterizing the mechanisms of SOCC have been carried out using HEK293 cells overexpressing proteins involved in regulating SOCE such as TRPC family members, Orai proteins (iCRAC channels) and the Ca2+ ER sensor, stromal interaction molecule-1 (STIM1), and under these conditions, 2-APB may inhibit calcium influx secondary to calcium release from the ER, via interaction with STIM, Orai, or both [29]. However, Ca2+ influx through 2-APB-sensitive ion channels in PC12+bPAC1hop cells does not appear to require coupling to depletion of intracellular stores, whether triggered by either ryanodine or IP3 receptor-dependent ER Ca2+ depletion. Identification of different protein targets for the apparent action of 2-APB may reflect expression levels of these proteins in non-endocrine compared to endocrine cells. While PACAP-evoked Ca2+ transients in PC12 cells is a net result of ryanodine-receptor gated intracellular Ca2+ release and extracellular influx though two classes of Ca2+ channels, PACAP-evoked sustained catecholamine release is exclusively driven by Ca2+ influx through 2-APB-sensitive ion channels. By coupling to different sources of Ca2+ with alternative physiological processes, neuropeptides such as PACAP can mediate acute effects, in addition to sustained responses required for processes such as secretion-synthesis coupling by not only regulating different sources of calcium but also coupling to different vesicle pools expressed in secretory cells. Since the PAC1hop receptor is the major isoform expressed in central and peripheral tissues, these studies reveal key mechanistic insights into the role of PACAP at different synapses controlled through the complex regulation of multiple signaling pathways, which combined with the ability of the PAC1 receptor to potently activate adenylate cyclase, forms the basis of PACAP-PAC1 receptor-mediated physiology.

Acknowledgements

This is work is supported by National Institute of Mental Health-Intramural Research Program Project ZO1-MH002386-23. Dr Tomris Mustafa and Jamie Walsh additionally supported by the Julius Axelrod Fellowship from the National Institute of Mental Health-Intramural Research Program. We would like to thank Chang-Mei Hsu and David Huddleston for technical assistance (Section on Molecular Neuroscience, NIMH). We also thank Dr Tamas Balla and Dr James T. Russell (NICHD, NIH-Intramural Research Program) for advice and consultation in preparation of this report.

Abbreviations

- AC

adenylate cyclase

- BCCs

bovine chromaffin cells

- Ca2+

calcium

- [Ca2+]i

cytosolic calcium concentration

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modification of Eagle’s Medium

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- IC3

third intracellular loop

- ICS

intracellular stores

- InsP3

inositol triphosphate

- KRB

Krebs-Ringer Buffer

- LDCVs

large-dense core vesicles

- Na+

sodium

- PACAP

pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide

- PAC1

PACAP-preferring type-1 receptor

- PC12

rat pheochromocytoma

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLC

phospholipase C

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase PCR

- SOCE

store-operated calcium entry

- SOCC

store-operated calcium channel

- TRP

transient receptor potential

- VGCCs

voltage-gated calcium channels

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Spengler D, Bweber C, Pantaloni C, Hlsboer F, Bockaert J, Seeburg PH, Journot L. Nature. 1993;365:170–175. doi: 10.1038/365170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pisegna JR, Wank SA. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:17267–17274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Geng G, Gaspo R, Trabelsi F, Yamaguchi N. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1997;42:R1339–R1345. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.4.R1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fukushima Y, Hikichi H, Mizukami K, Nagayama T, Yoshida M, Suzuki-Kusaba M, Hisa H, Kimura T, Satoh S. Am. J. Physiol. Regul.Integrative Comp. Physiol. 2001;281:R1562–R1567. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.5.R1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fukushima Y, Nagayama T, Kawashima H, Hikichi H, Yoshida M, Suzuki-Kusaba M, Hisa H, Kimura T, Satoh S. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2001;281:R495–R501. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.2.R495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Isobe K, Hakai T, Takuwa Y. Endocrinology. 1993;132:1757–1765. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.4.8384995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tanaka K, Shibuya I, Nagamoto T, Yamasha H, Kanno T. Endocrinol. 1996;137:956–966. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.3.8603609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].O’Farrell M, Marley PD. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1997;356:536–542. doi: 10.1007/pl00005088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Taupenot L, Mahata M, Mahata SK, O’Connor DT. Hypertension. 1999;34:1152–1162. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.5.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sakai Y, Hashimoto H, Shintani N, Ichibori A, Tomimoto S, Tanaka K, Hirose M, Baba A. Regul. Pept. 2002;109:149–153. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mustafa T, Grimaldi M, Eiden LE. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8079–8091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609638200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Palfrey HC, Artalejo CR. Neuroscience. 1998;83(4):969–89. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00453-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Duncan RR, Greaves J, Wiegand UK, Matskevich I, Bodammer G, Apps DK, Shipston MJ, Chow RH. Nature. 2003;422(6928):176–80. doi: 10.1038/nature01389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].García AG, García-De-Diego AM, Gandía L, Borges R, García-Sancho J. Physiol Rev. 2006;86(4):1093–131. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hamelink C, Lee HW, Grimaldi M, Eiden LE. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:5310–5320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05310.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Stroth N, Eiden LE. Neuroscience. 2010;165(4):1025–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tanaka K, Shibuya I, Uezono Y, Ueta Y, Toyohira Y, Yanagihara N, Izumi F, Kanno T, Yamashita H. J. Neurochem. 1998;70:1652–1661. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70041652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chatterjee TK, Sharma RV, Fisher RA. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:32226–32232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rausch DM, Iacangelo AL, Eiden LE. Mol. Endocrinol. 1988;2:921–927. doi: 10.1210/mend-2-10-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Grimaldi M, Cavallaro S. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:2767–2772. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ninomiya Y, Kishimoto T, Yamazawa T, Ikeda H, Miyashita Y, Kasai H. EMBO. 1997;16(5):929–34. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hahm SH, Hsu CM, Eiden LE. J Mol Neurosci. 1998;11(1):43–56. doi: 10.1385/JMN:11:1:43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kochegarov AA. Cell Calcium. 2003;33(3):145–62. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(02)00239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Taupenot L, Mahata SK, Wu H, O’Connor DT. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:863–876. doi: 10.1172/JCI1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kuri B, Chan S-A, Smith CB. J. Neurochem. 2009;110:1214–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hamelink C, Tjurmina O, Damadzic R, Young SW, Weihe E, Lee H-W, Eiden LE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:461–466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012608999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Iwasaki H, Mori Y, Hara Y, Uchida K, Zhou H, Mikoshiba K. Receptors Channels. 2001;7(6):429–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Liao YEC, Abramowitz J, Flockerzi V, Zhu MX, Armstrong DL, Birnbaumer L. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2895–2900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712288105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].DeHaven WI, Smyth JT, Boyles RR, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:19265–19273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801535200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]