Abstract

A 39-year-old man with poliosis of his lower eyelid lashes visited our clinic. He reported that his symptoms began with a few central lashes and then spread along the adjacent lashes during the ensuing 2 weeks. A pigmented nevus, approximately 4 mm in diameter, was identified just above the white lashes without surrounding skin depigmentation. No specific findings were identified with regard to the patient's general health or serologic and radiologic testing. Excisional biopsy of the pigmented nevus was performed. On histopathologic examination, infiltration of the dermis by numerous lymphocytes and melanophages was observed. The poliosis was ultimately diagnosed as a presenting sign of the halo phenomenon in the regressive stage of a melanocytic nevus.

Keywords: Halo nevus, Halo phenomenon, Poliosis

Poliosis (derived from polios, meaning gray) is defined as a localized area of hypopigmented hair caused by a reduction or absence of melanin in a group of follicles. Acquired poliosis of the eyelashes has been described in several ophthalmic conditions, including blepharitis, sarcoidosis, sympathetic ophthalmia, herpes zoster, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome, vitiligo, tuberous sclerosis, post-irradiation, and with topical administration of prostaglandin F2 analogues [1-5]. We encountered a case of unilateral poliosis not associated with any of these ophthalmic conditions. The case proved to be an unusual presentation of a halo nevus. To the best of our knowledge this is the first such case reported regarding the eyelid.

Case Report

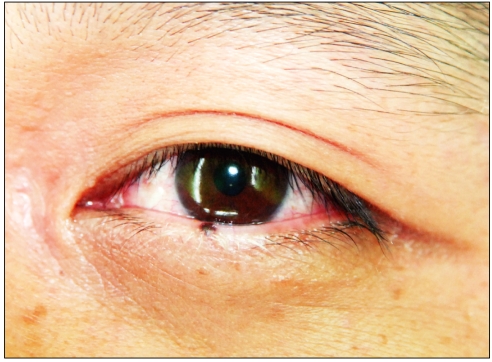

A 39-year-old man visited our clinic with a 2-week history of whitening of the eyelashes of his left lower lid. The patient reported that this started with 1 to 2 lashes on the central part of his eyelid and that adjacent eyelashes subsequently became involved over the next few days. Otherwise the patient was in excellent health with no significant medical history; he had no known drug allergies and was on no chronic medications. There was no associated family history of vitiligo, poliosis, or autoimmune disorders such as VKH or sarcoidosis. On examination, a pigmented skin nevus, approximately 4 mm in diameter, was noted above a patch of white eyelashes on the central aspect of the left lower eyelid (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Poliosis with a melanocytic nevus on the central eyelid.

According to the patient, the nevus had existed and remains unchanged since childhood. No other abnormalities of the eyelid were noted and there was no vitiligo or signs of periocular inflammation.

His visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes and there were no significant findings in the anterior segment or fundus. Serological tests for autoimmunity (antinuclear, antimitochondrial, and antismooth muscle antibodies) were negative and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing failed to demonstrate types HLA-DR4 or Dw53. Radiological examination of the chest and lumbar spine revealed no abnormalities. No organism was isolated from swabs collected from the patient's eyelid.

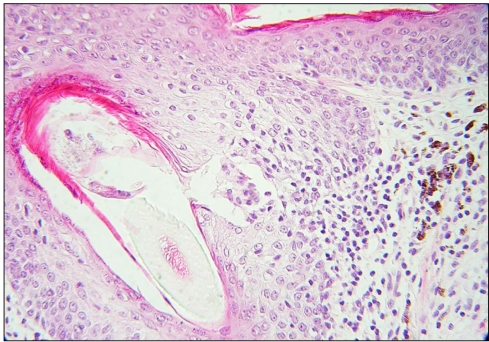

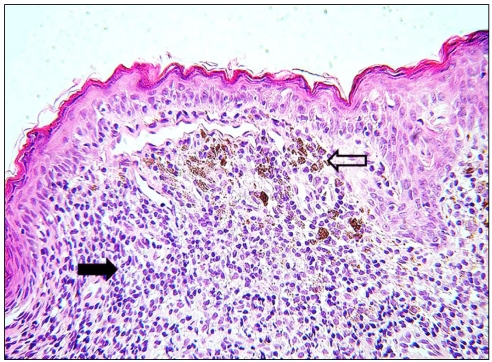

Excisional biopsy of the central eyelid, including the pigmented nevus and white eyelashes, was performed. On histopathologic examination, the nevus cells appeared unremarkable and showed no evidence of malignancy. Marked deficiency of melanocytes in the hair follicles was visible as compared with the normal overlying epidermis (Fig. 2). Infiltration of inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes and macrophages, was observed in the dermis (Fig. 3, arrow). Numerous melanocytic cells were observed at the dermo- epidermal junction (Fig. 3, open arrow). The final histopathologic diagnosis was a melanocytic halo nevus undergoing regression.

Fig. 2.

No melanocytes are seen in the hair follicles, while melanocytes are observed in the overlying epidermis (H&E, ×40).

Fig. 3.

Melanocytes (open arrow) in the dermis display maturation with progressive descent, much of the dermal component is obscured by a dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (arrow) (H&E, ×40).

Discussion

The majorities of halo nevi are acquired compound melanocytic nevi and appear in childhood and early adolescence. The site of predilection is the trunk and the back, especially when there are multiple lesions [6].

Patients with halo melanocytic nevi usually seek medical attention when their pigmented lesions develop a rim of depigmentation. Over time, halo nevi undergo specific changes. In stage I, the central nevus remains brown in color or its pigment can disappear leading to a pink-colored papule (stage II). Then the central papule disappears, leading to a circular area of depigmentation (stage III). Finally, the depigmented area may repigment (stage IV), leaving no trace of its existence [7].

The underlying pathophysiology of the halo phenomenon is not well understood, but may possibly be the result of an immune response leading to nevus cell destruction.

There are several theories regarding the pathogenesis of halo nevi. Some authors suggest an autoimmune response directed against antigenic changes of dysplastic nevi while others regard it as an autoimmune phenomenon against melanocytes, as occurs in vitiligo [8,9]. However, cellular and antibody-mediated immune mechanisms seem to be heavily involved in both theories and it is now well accepted that the inflammatory response is predominantly lymphocytic in nature, often with the addition of a small number of melanophages [10].

There are four histologic forms of halo nevi described: (a) inflammatory halo nevus, (b) noninflammatory nevus, (c) halo nevus without halo or halo nevus phenomenon, and (d) halo dermatitis around a melanocytic nevus (Mayerson's nevus) [11]. A halo nevus without the halo phenomenon is very rare and can only be diagnosed by histology.

There have been only a few reports regarding unusual clinical features of halo nevi. Zack et al. [12] and Kageshita et al. [13] described spontaneous regression of congenital nevi without the development of the halo phenomenon. Sotiriadis et al. [6] reported one case of a halo nevus without the halo phenomenon which developed on the trunk of a 5-year-old girl. They reported pathologic findings of a thin epidermis with marked orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and dense lymphocytic infiltration intermingled with melanocytes; these findings were consistent with the diagnosis of a halo nevus.

A T-cell-mediated autoimmune response leading to melanocyte destruction with resultant poliosis and associated halo nevi in VKH disease has been suggested. However, our case exhibited no evidence of autoimmune disease and no halo phenomenon or vitiligo [6].

In our case only histopathologic findings, such as infiltration of lymphocytes and melanophages, suggested the regression phase of the melanocytic halo nevus. Total loss of melanocytes in eyelash follicles may be an isolated sign of the halo phenomenon without depigmentation of the skin.

Despite an in-depth review of the literature, we did not encounter documentation of poliosis without skin depigmentation in a halo nevus. The only reports of halo nevi of the eyelids were accompanied by vitiligo, not poliosis. Also, a case of poliosis with a conjunctival melanoma has been described [14].

One possible, though very unlikely, explanation for the presence of poliosis without skin depigmentation occurring in this case may be a predilection of melanin-rich hair follicles for immunologic reactivity. It is not possible for us to state with certainty why this may have occurred in the setting of a halo nevus undergoing regression, although it is very likely that the inflammation resulted from an exaggerated cell-mediated immune response.

In conclusion, we herein present a case of a halo nevus with poliosis of the eyelashes as the only sign of the halo phenomenon. No such cases have previously been reported. Further analysis is needed to elucidate the mechanism of spontaneous regression of a halo nevus without depigmentation.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Bertolino AP, Freedberg IM. Hair. In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al., editors. Dermatology in general medicine. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. pp. 671–696. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moorthy RS, Inomata H, Rao NA. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39:265–292. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goto H, Rao NA. Sympathetic ophthalmia and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1990;30:279–285. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199030040-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagoner MD, Albert DM, Lerner AB, et al. New observations on vitiligo and ocular disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:16–26. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(83)90450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CS, Wells J, Craig JE. Topical prostaglandin F(2 alpha) analog induced poliosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:965–966. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sotiriadis D, Lazaridou E, Patsatsi A, et al. Does halo nevus without halo exist? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1394–1396. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnhill RL, Fitzpatrick TB, Fandrey K, editors. Color atlas and synopsis of pigmented lesions. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1995. pp. 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mihara M, Nakayama H, Aki T, et al. Cutaneous nerves in cafe au lait spots with white halos in infants with neurofibromatosis: an electron microscopic study. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:957–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnhill RL, Llewellyn K. Benign melanocytic neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, editors. Dermatology. London: Mosby; 2003. p. 1770. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Murphy GF, et al. Halo nevus. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, Murphy GF, editors. Lever's histopathology of the skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 747–749. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elder D, Elenitsas R. Benign pigmented lesions and malignant melanoma. In: Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky C, Johnson B Jr, editors. Lever's histopathology of the skin. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zack LD, Stegmeier O, Solomon LM. Pigmentary regression in a giant nevocellular nevus: a case report and a review of the subject. Pediatr Dermatol. 1988;5:178–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1988.tb01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kageshita T, Inoue Y, Ono T. Spontaneous regression of congenital melanocytic nevi without evidence of the halo phenomenon. Dermatology. 2003;207:193–195. doi: 10.1159/000071794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerra-Tapia A, Isarria MJ. Periocular vitiligo with onset around a congenital divided nevus of the eyelid. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:427–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]