Abstract

The aim of the present study was to characterize the antigenic specificity of the humoral immune response made by cats infected with the feline hemoplasma, Mycoplasma haemofelis. A crude M. haemofelis antigen preparation was prepared from red blood cells (RBCs) collected from a cat at the time of a high level of bacteremia. Plasma samples were collected from six cats before and after experimental infection with M. haemofelis, with regular sampling being performed from 15 to 149 or 153 days postinfection (dpi). Preinfection RBC membrane ghosts were prepared from these six cats and used to identify erythrocyte proteins that may have contaminated the M. haemofelis antigen preparation. The M. haemofelis antigen preparation comprised 11 protein bands. The immunodominant bands on Western blotting with infected cat plasma had molecular masses of 78, 68, 60, 48, and 38 kDa. Most cats (n = 5) had plasma antibody that reacted with at least one band (always including the one of 68 kDa) at 15 dpi, and all cats were seroreactive by 29 dpi. The maximum number of antibodies from an individual animal specific for an antigen was identified in plasma collected from 57 to 99 dpi. Contamination of the M. haemofelis antigen preparation with RBC membrane proteins was observed. The contaminating RBC proteins had molecular masses of from 71 to 72 kDa (consistent with band 4.2) and 261 and 238 kDa (consistent with spectrin), and these were recognized by all plasma samples. A range of M. haemofelis antigens is recognized by cats infected experimentally with the organism. These represent possible targets for immunoassays, but care must be taken to prevent false-positive results due to host protein contamination.

Feline infectious anemia is caused by the feline hemotropic mycoplasmas, also known as hemoplasmas, which are wall-less, epicellular, erythrocytic bacteria that have not yet been cultured in vitro. Three species of feline hemoplasmas which differ in their pathogenicities exist: Mycoplasma haemofelis, “Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum,” and “Candidatus Mycoplasma turicensis” (6, 20, 21, 28, 29). M. haemofelis is the most pathogenic species, and infection with this organism often results in severe hemolytic anemia in the absence of underlying immunocompromise. An immunological mechanism may be involved in the lysis of red blood cells (RBCs), as positive Coombs’ (direct antiglobulin) tests, indicating the presence of erythrocyte-bound antibodies, have been reported in previous studies of hemoplasma infections in a number of species, including cats (5, 7, 13, 27).

The inability to culture feline hemoplasmas, including M. haemofelis, in vitro has limited the development of protein-based diagnostic immunoassays. Studies investigating the Mycoplasma proteins recognized by the immune system of infected cats (1), pigs (Mycoplasma suis) (12), and mice (Mycoplasma haemomuris) (23) have used organisms isolated from the blood of acutely infected animals as the source of antigen. M. haemofelis-infected cats have been shown to have serum antibodies reactive with five major M. haemofelis antigens with molecular masses of 150, 52, 47, 45, and 14kDa. These antibodies were identified in serum samples collected between 14 and 60 days postinfection (dpi) (1).

We have recently investigated the kinetics and outcomes of experimental infection with each of the feline hemoplasma species, including M. haemofelis (26, 27). As part of those studies, plasma samples were collected for 22 weeks following M. haemofelis infection, to enable more extensive characterization of proteins recognized by the immune system of infected cats and to attempt to determine whether autoantibodies specific for erythrocyte membrane antigens were induced by the infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cats and samples.

Seven barrier-maintained, specific-pathogen-free-derived domestic shorthaired cats (7 months old, n = 6; 2 years old, n = 1; neutered males, n = 4; entire females, n = 3) were used in this study. All cats were experimentally infected with M. haemofelis; and details of the experimental procedures, the inoculating doses administered, and infection monitoring procedures have been described previously (26, 27). The cats were designated HF1, HF2, HF4, HF6, HF8, HF12, and HF14, with the discontinuous numbering being due to the inclusion of additional cats in the parallel studies mentioned previously (26, 27). Briefly, infection of the cats was carried out by obtaining heparinized blood from barrier-maintained donor cats chronically infected with M. haemofelis. The blood type of the donor cats and all recipients was predetermined to be type A (RapidVet-H blood typing cards; DMS Laboratories Inc., NJ). Fresh blood was collected from the donors and injected intravenously into the recipients. These inocula comprised 2 ml of heparinized blood (infective doses, 7.21 × 107 copies for cat HF14 and 1.55 × 108 M. haemofelis copies for the other cats), given via preplaced cephalic intravenous catheters within 5 min of collection from the donors. All procedures and experiments described were undertaken under a project license approved under the United Kingdom Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

As described previously (26, 27), EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples were regularly collected from all cats and subjected to real-time PCR (quantitative PCR [qPCR]) to confirm that M. haemofelis infection was absent before inoculation and present postinfection (26, 27). Seven days before infection (day −7), on the day of infection (day 0), and approximately every 2 weeks thereafter until day 149 (cat HF2) or 153 (cats HF1, -4, -6, -8, and -12), an additional 1-ml volume of EDTA-anticoagulated blood was collected from each cat and centrifuged (2,200 × g, 3 min), and the plasma was removed and stored at −20°C until use. A pooled plasma sample was made by mixing an equal volume of the preinfection plasma samples collected during the study. Plasma samples from EDTA-anticoagulated blood (the RBCs were used for other purposes, e.g., Coombs’ test) were used in order to minimize the total volume of blood collected from the animals and to comply with the terms of the study's project license.

Antigen preparation. (i) M. haemofelis.

Whole blood was obtained from cat HF14 at a time of the presence of a high M. haemofelis blood copy number, as determined by qPCR (4 × 109 M. haemofelis copies/ml, 11 dpi) (26). At the time of euthanasia, once deep general anesthesia had been induced with intravenous pentobarbitone, approximately 100 ml of blood was collected into Alsever's solution (1:1, vol/vol; Sigma-Aldrich Ltd., Poole, Dorset, United Kingdom) by cardiac puncture prior to completion of the anesthetic overdose. M. haemofelis was isolated from the blood using the methods described by Hoelzle et al. (9, 12). Briefly, RBCs were sedimented by centrifugation at 600 × g for 10 min, the plasma and buffy coat were aspirated, and the RBCs were washed and centrifuged in an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.15 M, pH 7.4). The PBS and remaining buffy coat were aspirated, and the wash was repeated twice more. The final packed, washed RBCs were incubated in PBS containing 0.15% Tween 20 and 3% (wt/vol) EDTA and then incubated for 30 min at ambient temperature in a vertical shaker (speed, 150 rpm) to dislodge the M. haemofelis. The debris and erythrocytes were pelleted by centrifugation at 600 × g for 10 min, and the resultant supernatant was centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to pellet the M. haemofelis. The supernatant was removed, the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml PBS, the mixture was centrifuged through 20% sodium diatrozoate meglumine and diatrozoate sodium (76% Urografin; Bayer plc, Newbury, Berkshire, United Kingdom) at 15,000 rpm for 40 min at 4°C, and the final pellet was resuspended in 1.0 ml PBS.

The resulting M. haemofelis antigen preparation was depleted of any contaminating albumin or IgG using the ProteoExtract albumin/IgG removal kit (Calbiochem, Merck Chemicals Ltd., Nottingham, United Kingdom), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The flowthrough and the wash from the columns were added to a 20K iCON concentrator (Pierce Biotechnology, Fisher Scientific United Kingdom Ltd., Loughborough, Leicestershire, United Kingdom) and centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 1 h. The protein concentration in the retained solution (approximately 1 ml) was measured using a Qubit apparatus (Invitrogen Ltd., Paisley, Scotland) before storage at −80°C.

A similar procedure was attempted using blood from cats infected with “Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum” (4.6 × 107 “Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum” copies/ml, 21 dpi) and “Candidatus Mycoplasma turicensis” (1 × 105 “Candidatus Mycoplasma turicensis” copies/ml, 17 dpi), but insufficient antigen was recovered, even when blood was collected at the peak of the hemoplasma copy number for these species (unpublished observations).

(ii) RBC membrane ghosts.

RBC membrane ghosts were prepared from 1 ml EDTA-anticoagulated blood from the six plasma source cats (HF1, -2, -4, -6, -8, and -12) prior to infection, using the methods described by Barker (3). Briefly, RBCs from 1 ml EDTA-anticoagulated blood were washed six times in 10 volumes of PBS, with aspiration of the supernatant and buffy coat being performed between washes. The RBCs were lysed by adding 10 volumes of ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.6) and pelleted by centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant and opaque buttons of residual leukocytes were removed, using a pipette, leaving the translucent RBC membranes. The membranes were washed a minimum of four times in ice-cold lysis buffer, until the supernatant was clear of hemoglobin. The concentration of protein in the final solution was measured by the Qubit apparatus and stored at −80°C prior to use.

PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was performed using the NuPAGE electrophoresis system (Invitrogen Ltd., Paisley, United Kingdom) under reducing conditions, and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using an XCell minicell and blot module (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. NuPAGE Novex 4 to 12% bis-Tris precast gels, NuPAGE morpholinepropanesulfonic acid running buffer, and NuPAGE LDS (lithiun dodecyl sulfate) sample buffer (all from Invitrogen Ltd.) and the M. haemofelis or RBC membrane antigen (20 μg per well) were used for the investigation of the humoral immune responses. Protein transfer was performed using the NuPAGE transfer buffer (Invitrogen), and a prestained molecular weight standard (All Blue Precision Plus protein standard; Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom) was included on each gel to monitor the transfer efficiency and to allow calculation of the molecular mass. The NuPAGE large protein blotting kit (Invitrogen), which included 3 to 8% Tris-acetate gels, the HiMark prestained high molecular weight protein standard, and 0.45-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose membranes, was used to further investigate the antigenic proteins in the RBC membrane preparations, as this gave better separation of the high-molecular-weight proteins.

After transfer, the nitrocellulose membranes were blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk in TBST (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.6) for 2 h. The membranes were then cut into strips, each including a lane of M. haemofelis antigen and RBC membrane ghosts from the individual cat. The strips were probed overnight with a 1/250 dilution of plasma (collected on days −7, 0, 15, 29, 43, 57, 71, 85, 99, 111, 125, 139, and 149 or 153) in TBST-5% nonfat milk. After the strips were washed, binding of plasma antibody was identified by use of an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-cat IgG H+L Fab′ antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Europe Ltd., Newmarket, Suffolk, United Kingdom) diluted 1/20,000 in TBST-5% nonfat milk and applied for 2 h. The membranes were washed three times with TBST between steps, and all incubations were at room temperature on a rocking platform. Following the final washes, visualization was achieved using a Lumi-Phos WB chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce Biotechnology) and exposure to Kodak Bio-max film (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min.

A negative control, which consisted of omitting the incubation with a plasma sample, was performed to control for reactivity between secondary antibody and the M. haemofelis antigen and RBC membrane ghosts. The pooled plasma sample (10 μl of a 1/100 dilution), incubated with the secondary antibody, was used to identify bands resulting from plasma protein contamination of the antigen preparations.

Images of the Western blots were captured using a document scanner and analyzed using TotalLab TL100 software (Nonlinear Dynamics Limited, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom), in order to allow correction for gel artifacts and comparison of the banding patterns obtained from antigen preparations and different plasma samples.

RESULTS

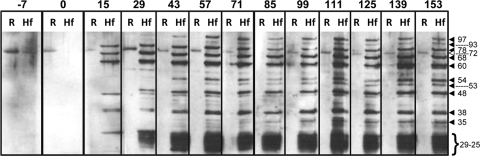

Western blots were performed with RBC membrane ghosts and M. haemofelis antigen preparations using plasma samples collected from six cats infected with M. haemofelis between 0 and 149 or 153 dpi. Antibodies with specificities for 12 different bands in the M. haemofelis antigen preparation (97, 93, 78, 72, 68, 60, 54, 53, 48, 38, 35, and 29 to 25 kDa) and for a 71- to 72-kDa band in the RBC membrane ghosts were induced (Fig. 1). The antibody specific for the 71- to 72-kDa protein identified in the RBC ghosts and the M. haemofelis antigen preparations was present in plasma collected preinfection (days −7 and 0) and postinfection, although the intensity of this band varied when plasma samples taken at different time points were compared for the same animal. This band was not considered to be of M. haemofelis origin and was excluded from the analysis of the immune response to M. haemofelis. None of the 12 preinfection plasma samples contained antibody to any of the other 11 M. haemofelis bands. No protein bands were identified when the secondary antibody alone was incubated with the antigen preparations (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Western blot of RBC membrane antigen (R) and M. haemofelis antigen (Hf) probed with plasma samples (a 1/250 dilution) collected preinfection (days −7 and 0) and postinfection (15, 29, 43, 57, 71, 85, 99, 111, 125, 139, and 153 dpi) from cat HF4. The calculated molecular masses for the major bands (kDa) are shown by arrowheads. The open triangle corresponds to the 71- to 72-kDa band 4.2 protein identified in both RBC and M. haemofelis antigen preparations.

Five of the six cats had developed antibody to at least one M. haemofelis band (which always included the 68-kDa band) at 15 dpi, and all six cats had seroconverted by 29 dpi (Table 1). The maximum number of M. haemofelis bands recognized by individual cats ranged from 8 to 11, with the 78-, 68-, 60-, 48-, and 38-kDa bands being recognized by plasma antibodies from all cats. The same five bands were those that tended to be recognized first. The maximum number of M. haemofelis bands recognized by an individual was in samples collected between 57 and 99 dpi. There was some variation in band intensity with individual plasma samples after this time, but this was not related to any changes in the infection kinetics or clinical parameters in that particular animal (Table 1). The band between 29 and 25 kDa appeared as a single broad band in the majority of cats at most time points, but one cat had reactivity initially (15 dpi) only with the 29-kDa band (Fig. 1) and another had distinct reactivity with bands within the 29- and 25-kDa range at 15 dpi.

TABLE 1.

M. haemofelis antigens recognized during the humoral immune response in six cats experimentally infected with the organism

| Calculated molecular mass (kDa) of antigen band | No. of animals reacting to individual bands at the following dpi: |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −7 | 0 | 15 | 29 | 43 | 57 | 71 | 85 | 99 | 111 | 125 | 139 | 153 | |

| 97 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 93 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 78a | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| 68a | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 60a | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 54 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 53 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 48a | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 38a | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 29, 25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Avg no. of bands detected | 0 | 0 | 3.8 | 5.7 | 6.5 | 8.5 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 8.8 |

These bands were recognized by all cats and tended to be recognized first and were thus considered the major antigenic determinants.

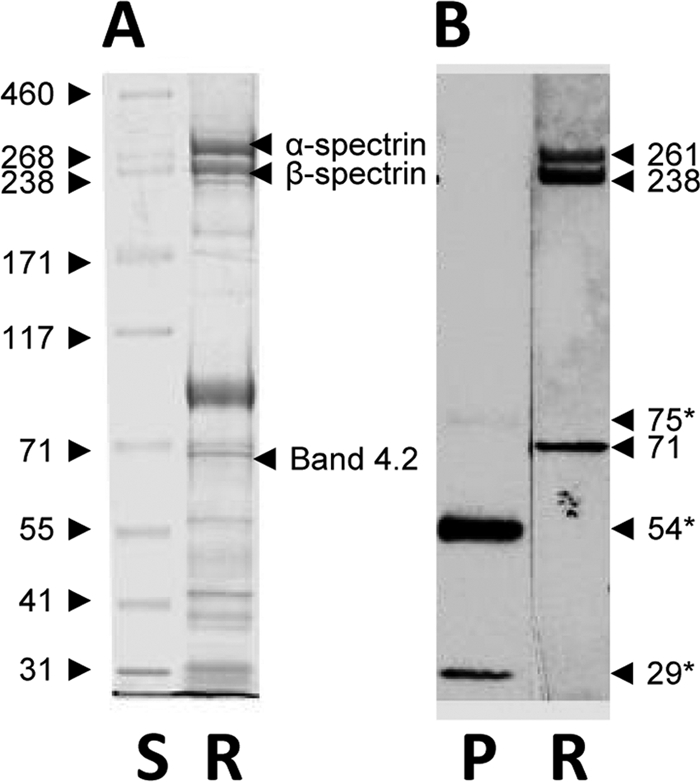

The nature of the 71- to 72-kDa band identified in the M. haemofelis and RBC membrane antigen preparations by both preinfection and postinfection plasma was further examined by comparison of feline RBC membrane proteins separated by PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue, a Western blot of the RBC membrane proteins probed with a pool of the plasma samples used in the study, and the pooled plasma sample probed with the secondary antibody (Fig. 2). Bands at 54 kDa and 29 kDa were identified in the pooled plasma by the secondary antibody, corresponding to the gamma heavy chain of IgG and immunoglobulin light chains. In addition, a faint band was present at 75 kDa, which likely represents some cross-reactivity with the μ heavy chain of IgM. These bands were in contrast to the three bands (261, 238, and 71 kDa) detected in the RBC membrane antigen preparation probed with the plasma pool (Fig. 2) and the 78 individual plasma samples used in the study (data not shown). The high-molecular-mass bands (261 and 238 kDa) likely corresponded to the bands for α- and β-spectrin that were visible on the Coomassie blue-stained RBC membrane ghost gel (Fig. 2). The band at 71 to 72 kDa did not correspond to the faint 75-kDa band detected in the plasma pool but was the same weight as band 4.2 in the Coomassie blue-stained gel.

FIG. 2.

A Coomassie blue-stained polyacrylamide gel (A) of RBC membrane antigen (R) and a Western blot (B) of a pooled plasma sample (lane P; days −7 and 0, all cats) and RBC membrane antigen (lanes R) probed with the pooled plasma sample (1/250 dilution). The molecular mass (kDa) of each protein standard (lane S) is given on the left side. The calculated molecular mass (kDa) of each identified band is given on the right side with the likely RBC membrane proteins corresponding to the bands (3, 24). Three bands (*) were detected in the plasma sample incubated with the secondary antibody alone and correspond to immunoglobulin light chains (29 kDa), the γ heavy chain of IgG (54 kDa), and a faint band corresponding to μ heavy chain of IgM (75 kDa).

DISCUSSION

The study described here has characterized the specificity of the plasma antibody response to M. haemofelis proteins made by cats experimentally infected with M. haemofelis. This humoral immune response was monitored for 22 weeks following infection. To date, M. haemofelis has not been cultured in vitro, and the only means of producing antigen for such studies is by in vivo amplification and isolation from the blood of an infected cat (1). Similar techniques have been applied to the preparation of antigen from M. suis (9, 12) and M. haemomuris (23). Contamination of M. haemofelis antigen preparations with host blood-derived proteins is a recognized problem, and such contaminants may originate from the cellular components (RBCs and white blood cells) and the plasma. In order to maximize the amount of antigen recovered, blood was collected from an experimentally infected cat at the time of the presumptive peak M. haemofelis copy number (11 dpi) and before the onset of anemia and Coombs’ test positivity (27). Blood collected after the onset of anemia and Coombs’ test positivity was susceptible to severe hemolysis during the isolation procedure, resulting in hemoglobin and RBC membrane contamination of the M. haemofelis preparations (unpublished observations). An albumin and IgG depletion step was included in the M. haemofelis antigen preparation procedure, as immunoglobulin contamination of M. suis preparations has been reported (12). Bands consistent with the heavy and light chains from IgG were not detected when the M. haemofelis antigen preparation was incubated with the secondary antibody alone. The present study has used plasma harvested from EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples collected for other assays rather than serum, in order to minimize the volume of blood collected from the animals. No problems with the use of plasma rather than serum in the Western blotting procedure were recognized.

A 71- to 72-kDa protein band was detected in the M. haemofelis and RBC membrane antigen preparations by all pre- and postinfection plasma samples but was not detected when the secondary antibody was used alone. This protein band has a molecular mass equivalent to that for erythrocyte protein band 4.2 (16, 24) and correlated with band 4.2 identified on a Commassie blue-stained polyacrylamide gel of RBC membrane proteins. This band was not of a size that would be consistent with the immunoglobulin light chains or γ or μ heavy chains identified in the blot of the pooled plasma sample. Therefore, reactivity involving the 71- to 72-kDa band was considered the result of contamination of the M. haemofelis antigen preparation by host erythrocyte proteins. These cats also had plasma antibody reactive with α- and β-spectrin in the RBC membrane ghost preparations, and this antibody was present both before and after M. haemofelis infection. These bands were intermittently visible in the Western blots with the M. haemofelis antigen preparation, presumably due to their high molecular weight and inconsistent transfer when the standard blotting system was used. Naturally occurring autoantibodies to erythrocyte cytoskeleton proteins, including the spectrins, have been reported in a number of species, including humans (2, 17) and dogs (4). The human antispectrin antibodies have been shown to cross-react with a protein migrating to an equivalent position as band 4.2 (17). These physiological autoantibodies specific for erythrocyte proteins have a role in the removal of damaged and senescent RBCs (reviewed in reference 15).

The plasma of all cats contained antibody reactive with a broad band with a molecular mass of 25 to 29 kDa. This band appeared to be made up of a number of individual bands of similar sizes when two of the plasma samples collected at 15 dpi were used but was present as a single band with all other positive plasma samples. A similar band was present in previous studies of the antibody responses to M. haemofelis (1) and M. suis (12) and corresponds to the immunoglobulin-containing area identified by two-dimensional SDS-PAGE/Western blotting of M. suis (10). This broad protein band may therefore be composed of host-derived proteins. The size of this protein would be consistent with that of immunoglobulin light chain, but the band was not recognized by the secondary antibody alone. Further work is required to determine the identity of this band.

The major antigenic determinants of M. haemofelis to which infected cats respond serologically had molecular masses of 78, 68, 60, 48, and 38 kDa. All cats produced antibodies reactive with all of these bands by 57 dpi. A previous study found significant reactivity to M. haemofelis determinants with molecular masses of 150, 52, and 14 kDa by 30 dpi (1). Antibodies reactive with M. haemofelis proteins of 53 and 54 kDa were found in the plasma of cats in the present study, but the former specificity was identified in only one cat and the latter was seen in only four cats by 57 dpi, which is the time point closest to the time of collection of the last sample (60 dpi) analyzed in the study by Alleman et al. (1).

Mice infected with M. haemomuris develop serum antibodies to Mycoplasma determinants with molecular masses of 118, 65, 53, 45, and 40 kDa at 42 dpi (23). Pigs infected with M. suis produce antibodies reactive with major M. suis proteins of 70, 45, and 40 kDa and minor proteins of 83, 73, 61, 57, and 33 kDa. In these pigs, antibody specific for the major bands was present as early as 7 dpi and was well established by 14 dpi (12). The variation in the molecular masses of the M. haemofelis determinants detected in our study compared with those from previous studies may be due to the experimental methods used or the hemoplasma species investigated. For instance, the major determinants described in the M. suis study (70, 45, and 40 kDa) may correspond to the M. haemofelis determinants of 68, 48, and 38 kDa described in the present study, but use of different acrylamide gel concentrations (4% to 12% gradient gel versus 10% gel) and buffer systems in the two studies may have resulted in slightly different migration rates, affecting the calculation of molecular mass. Alternatively, these differences may reflect variations between the Mycoplasma species, as they reside in different clades within the hemoplasmas, as determined by 16S rRNA and RNase P phylogenetic analyses (14, 18, 20, 22, 25).

Later studies of the immune response to M. suis identified the 70-kDa protein (HspA1) to be a DnaK-like protein (10) and the 40-kDa protein (MSG1) to be a surface-localized adhesion protein with properties similar to those of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (11). These two proteins may correspond to the 68-kDa protein (HspA1) and 38-kDa protein (MSG1) recognized in the M. haemofelis antigen preparation in the present study. These proteins have been evaluated for use in diagnostic immunoassays (10), and the latter has been evaluated as a potential vaccine candidate (8). A recent study investigating “Candidatus Mycoplasma turicensis” infection found that the majority of cats seroconverted 3 to 4 weeks following infection to a recombinant, partial M. haemofelis MSG1 protein by Western blotting (19). In addition, this study demonstrated reactivity to this recombinant protein in plasma collected from a cat infected with M. haemofelis at 6 weeks postinfection and one infected with “Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum” at 21 weeks postinfection. Therefore, the results of that study agree with the present findings, as five of the cats reported here seroconverted to positivity for the 68-kDa protein by 29 dpi.

The cats whose blood was utilized in the present study for the Western blots developed anemia and had positive Coombs’ test results from 15 to 50 dpi (27). There was no correlation between the M. haemofelis antigenic determinants recognized and the development and subsequent disappearance of RBC-associated antibody. The first occasion on which the Coombs’ test was positive correlated with the day on which the first plasma sample was collected for the analysis described in this study. Disappearance of the RBC-associated antibody did not correlate with the development or loss of reactivity to any particular M. haemofelis antigenic determinant.

The results of the present study demonstrate that a range of Mycoplasma and erythrocyte antigenic determinants are recognized by circulating antibodies in cats with M. haemofelis infection. The autoantibodies directed against the RBC membrane proteins α- and β-spectrin and the protein equivalent to band 4.2 were present in both preinfection and postinfection samples. These likely represent physiological autoantibodies involved in the removal of senescent erythrocytes. It is of note that cats become Coombs’ test positive only postinfection. It remains to be determined whether the erythrocyte-bound antibody (as opposed to the circulating antibody investigated here) is specific for surface M. haemofelis antigens or erythrocyte autoantigens and whether the antigenic specificity of antibody eluted from the erythrocytes of M. haemofelis-infected cats differs from that of the circulating antibody pool.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant no. 077718).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alleman, A. R., M. G. Pate, J. W. Harvey, J. M. Gaskin, and A. F. Barbet. 1999. Western immunoblot analysis of the antigens of Haemobartonella felis with sera from experimentally infected cats. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1474-1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballas, S. K. 1989. Spectrin autoantibodies in normal human serum and in polyclonal blood grouping sera. Br. J. Haematol. 71:137-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker, R. N. 1991. Electrophoretic analysis of erythrocyte membrane proteins and glycoproteins from different species. Comp. Haematol Int. 1:155-160. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker, R. N., T. J. Gruffydd-Jones, C. R. Stokes, and C. J. Elson. 1991. Identification of autoantigens in canine autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 85:33-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bundza, A., J. H. Lumsden, B. J. McSherry, V. E. Valli, and E. A. Jazen. 1976. Haemobartonellosis in a dog in association with Coombs’ positive anaemia. Can. Vet. J. 17:267-270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foley, J. E., and N. C. Pedersen. 2001. ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum,’ a low-virulence epierythrocytic parasite of cats. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:815-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvey, J. W., and J. M. Gaskin. 1978. Abstr. 45th Annu. Meet. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc., p. 117-123.

- 8.Hoelzle, K., S. Doser, M. Ritzmann, K. Heinritzi, A. Palzer, S. Elicker, M. Kramer, K. M. Felder, and L. E. Hoelzle. 2009. Vaccination with the Mycoplasma suis recombinant adhesion protein MSG1 elicits a strong immune response but fails to induce protection in pigs. Vaccine 27:5376-5382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoelzle, L. E., D. Adelt, K. Hoelzle, K. Heinritzi, and M. M. Wittenbrink. 2003. Development of a diagnostic PCR assay based on novel DNA sequences for the detection of Mycoplasma suis (Eperythrozoon suis) in porcine blood. Vet. Microbiol. 93:185-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoelzle, L. E., K. Hoelzle, A. Harder, M. Ritzmann, H. Aupperle, H. A. Schoon, K. Heinritzi, and M. M. Wittenbrink. 2007. First identification and functional characterization of an immunogenic protein in unculturable haemotrophic Mycoplasmas (Mycoplasma suis HspA1). FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 49:215-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoelzle, L. E., K. Hoelzle, M. Helbling, H. Aupperle, H. A. Schoon, M. Ritzmann, K. Heinritzi, K. M. Felder, and M. M. Wittenbrink. 2007. MSG1, a surface-localised protein of Mycoplasma suis is involved in the adhesion to erythrocytes. Microbes Infect. 9:466-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoelzle, L. E., K. Hoelzle, M. Ritzmann, K. Heinritzi, and M. M. Wittenbrink. 2006. Mycoplasma suis antigens recognized during humoral immune response in experimentally infected pigs. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13:116-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann, R., D. O. Schmid, and G. Hoffmann-Fezer. 1981. Erythrocyte antibodies in porcine eperythrozoonosis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2:111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansson, K. E., J. G. Tully, G. Bolske, and B. Pettersson. 1999. Mycoplasma cavipharyngis and Mycoplasma fastidiosum, the closest relatives to Eperythrozoon spp. and Haemobartonella spp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 174:321-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kay, M. 2005. Immunoregulation of cellular life span. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1057:85-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korsgren, C., J. Lawler, S. Lambert, D. Speicher, and C. M. Cohen. 1990. Complete amino acid sequence and homologies of human erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:613-617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lutz, H. U., and G. Wipf. 1982. Naturally occurring autoantibodies to skeletal proteins from human red blood cells. J. Immunol. 128:1695-1699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Messick, J. B., P. G. Walker, W. Raphael, L. Berent, and X. Shi. 2002. ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma haemodidelphidis’ sp. nov., ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma haemolamae’ sp. nov. and Mycoplasma haemocanis comb. nov., haemotrophic parasites from a naturally infected opossum (Didelphis virginiana), alpaca (Lama pacos) and dog (Canis familiaris): phylogenetic and secondary structural relatedness of their 16S rRNA genes to other mycoplasmas. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:693-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Museux, K., F. S. Boretti, B. Willi, B. Riond, K. Hoelzle, L. E. Hoelzle, M. M. Wittenbrink, S. Tasker, N. Wengi, C. E. Reusch, H. Lutz, and R. Hofmann-Lehmann. 2009. In vivo transmission studies of ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma turicensis’ in the domestic cat. Vet. Res. 40:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neimark, H., K. E. Johansson, Y. Rikihisa, and J. G. Tully. 2001. Proposal to transfer some members of the genera Haemobartonella and Eperythrozoon to the genus Mycoplasma with descriptions of ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma haemofelis,’ ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma haemomuris,’ ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma haemosuis’ and ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma wenyonii.’ Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:891-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neimark, H., K. E. Johansson, Y. Rikihisa, and J. G. Tully. 2002. Revision of haemotrophic Mycoplasma species names. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters, I. R., C. R. Helps, L. McAuliffe, H. Neimark, M. R. Lappin, T. J. Gruffydd-Jones, M. J. Day, L. E. Hoelzle, B. Willi, M. Meli, R. Hofmann-Lehmann, and S. Tasker. 2008. RNaseP RNA gene (rnpB) phylogeny of haemoplasmas and other Mycoplasma species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1873-1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rikihisa, Y., M. Kawahara, B. Wen, G. Kociba, P. Fuerst, F. Kawamori, C. Suto, S. Shibata, and M. Futohashi. 1997. Western immunoblot analysis of Haemobartonella muris and comparison of 16S rRNA gene sequences of H. muris, H. felis, and Eperythrozoon suis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:823-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steck, T. L. 1974. The organization of proteins in the human red blood cell membrane. A review. J. Cell Biol. 62:1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tasker, S., C. R. Helps, M. J. Day, D. A. Harbour, S. E. Shaw, S. Harrus, G. Baneth, R. G. Lobetti, R. Malik, J. P. Beaufils, C. R. Belford, and T. J. Gruffydd-Jones. 2003. Phylogenetic analysis of hemoplasma species: an international study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3877-3880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tasker, S., I. R. Peters, M. J. Day, B. Willi, R. Hofmann-Lehmann, T. J. Gruffydd-Jones, and C. R. Helps. 2009. Distribution of Mycoplasma haemofelis in blood and tissues following experimental infection. Microb. Pathog. 47:334-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tasker, S., I. R. Peters, K. Papasouliotis, S. M. Cue, B. Willi, R. Hofmann-Lehmann, T. J. Gruffydd-Jones, T. G. Knowles, M. J. Day, and C. R. Helps. 2009. Description of outcomes of experimental infection with feline haemoplasmas: copy numbers, haematology, Coombs’ testing and blood glucose concentrations. Vet. Microbiol. 139:323-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willi, B., F. S. Boretti, V. Cattori, S. Tasker, M. L. Meli, C. Reusch, H. Lutz, and R. Hofmann-Lehmann. 2005. Identification, molecular characterization, and experimental transmission of a new hemoplasma isolate from a cat with hemolytic anemia in Switzerland. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2581-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willi, B., S. Tasker, F. S. Boretti, M. G. Doherr, V. Cattori, M. L. Meli, R. G. Lobetti, R. Malik, C. E. Reusch, H. Lutz, and R. Hofmann-Lehmann. 2006. Phylogenetic analysis of “Candidatus Mycoplasma turicensis” isolates from pet cats in the United Kingdom, Australia, and South Africa, with analysis of risk factors for infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:4430-4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]