Abstract

The oomycetous, fungus-like, aquatic organism Pythium insidiosum is the causative agent of pythiosis, a life-threatening infectious disease of humans and animals living in tropical and subtropical areas of the world. Common sites of infection are the arteries, eyes, cutaneous/subcutaneous tissues, and gastrointestinal tract. Diagnosis of pythiosis is time-consuming and difficult. Radical excision of the infected organs is the main treatment for pythiosis because conventional antifungal drugs are ineffective. An immunotherapeutic vaccine prepared from P. insidiosum crude extract showed limited efficacy in the treatment of pythiosis patients. Many pythiosis patients suffer lifelong disabilities or die from an advanced infection. Recently, we identified a 74-kDa major immunodominant antigen of P. insidiosum which could be a target for development of a more effective serodiagnostic test and vaccines. Mass spectrometric analysis identified two peptides of the 74-kDa antigen (s74-1 and s74-2) which perfectly matched a putative exo-1,3-ß-glucanase (EXO1) of Phytophthora infestans. Using degenerate primers derived from these peptides, a 1.1-kb product was produced by PCR, and its sequence was found to be homologous to that of the P. infestans exo-1,3-ß-glucanase gene, EXO1. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays targeting the s74-1 and s74-2 synthetic peptides demonstrated that the 74-kDa antigen was highly immunoreactive with pythiosis sera but not with control sera. Phylogenetic analysis using part of the 74-kDa protein-coding sequence divided 22 Thai isolates of P. insidiosum into two clades. Further characterization of the putative P. insidiosum glucanase could lead to new diagnostic tests and to antimicrobial agents and vaccines for the prevention and management of the serious and life-threatening disease of pythiosis.

Oomycetes are a unique group of fungus-like eukaryotic microorganisms that belong to the stramenopiles of the supergroup Chromalveolates and are biochemically and genetically different from true fungi (13, 14, 20). Phylogenetic analysis showed that the oomycetes are more closely related to diatoms and algae (20). Many of the oomycetes are plant pathogens that cause significant agricultural losses each year, while some are capable of infecting humans and animals, including horses, dogs, cats, cattle, sheep, fish, and mosquitoes (13). Finding a way to control the infections caused by the oomycetes is challenging.

Pythium insidiosum is the only oomycete that causes life-threatening infectious disease in humans and animals (mostly horses and dogs). The disease state is called pythiosis, and it is endemic to tropical and subtropical regions (13, 19, 24). In nature, P. insidiosum inhabits swampy areas, where it is present in one of two forms: a right-angle branching mycelium and a biflagellate zoospore (25). The zoospore is a motile asexual morphotype that can germinate to produce mycelia on its natural hosts, such as water plants (25). Infection occurs when zoospores come in contact with humans or animals and invade as germinating hyphae (25). In humans, the most common sites of infection are arteries and eyes (19), while in animals, cutaneous/subcutaneous and gastrointestinal sites predominate (24).

High rates of morbidity and mortality of pythiosis are exacerbated by the lack of early diagnosis and effective treatments (19, 24). Diagnosis by culture identification is time-consuming and limited to experienced clinical laboratories (6, 29). Serological and PCR-based assays have been developed for facilitating the diagnosis of pythiosis (4, 9, 10, 12, 15-18, 26, 27, 34, 39, 42, 43). The PCR-based diagnostic procedure is complicated, and the necessary materials and equipment are not widely available. All of the reported serology-based assays require a crude extract of P. insidiosum as the antigen source. In our experience, batch-to-batch variation in the quality of the crude antigen leads to problems with the reproducibility of the serological assays. For each new antigen preparation, the assay protocol needs extensive reevaluation in regards to antigen concentration, the optimal dilution of the serum samples, cutoff points, and the effective concentration of other reagents before it is suitable for clinical use. In addition, recent reports of false-positive results for some diagnostic tests (12, 15) indicate a problem regarding the specificity of detection of the crude extract antigen. Taken together, these complications indicate an ongoing need for a more reliable and specific antigen source for the development of serological assays.

Use of conventional antifungal agents for treatment of pythiosis is ineffective because the oomycetes lack the drug-targeted ergosterol biosynthesis pathway (19, 38). Surgical removal of the affected organs (i.e., the eye or leg) is the main treatment to control the disease, but it leads to lifelong physical handicaps (19, 24). Despite intensive care, many pythiosis patients die from an advanced and aggressive infection. An immunotherapeutic vaccine prepared from crude extracts of P. insidiosum showed curative rates of up to 60% for horses, 56% for humans, and 33% for dogs with pythiosis (19, 28, 44). Improved outcomes can result from early diagnosis and effective treatment, so these are still important health care goals.

A major immunodominant antigen of P. insidiosum could be a target for development of a more reliable serodiagnostic test, as well as a more effective vaccine, for patients with pythiosis. We recently identified 74- and 34- to 43-kDa major immunodominant antigens in the extracts of P. insidiosum human isolates by Western blot analysis (18). Only the 74-kDa immunodominant antigen was found in all P. insidiosum isolates and recognized by all pythiosis sera tested. Control sera from healthy individuals, patients with thalassemia (a major predisposing factor of pythiosis), and patients with various other infectious diseases failed to react with this 74-kDa immunogen (18), suggesting that this protein is specifically recognized by anti-P. insidiosum antibodies. The Western blot profiles of P. insidiosum extracts (probed with anti-P. insidiosum antibodies) were compared to those of Pythium aphanidermatum and Pythium deliense (which are phylogenetically related to P. insidiosum but which are not pathogenic for humans or animals), as well as those of Conidiobolus coronatus and Rhizopus spp. (which are zygomycetic fungi that share microscopic features with P. insidiosum) (18). The 74- and 34- to 43-kDa immunogens were absent in the Western blot profiles of the nonpathogenic Pythium spp. and zygomycetic fungi tested, suggesting that these immunogens are unique to P. insidiosum. Identification and characterization of these immunogenic proteins and their genes are the first step to explore their functional roles and to develop downstream clinical applications. Here, we report on our use of mass spectrometric (MS) and molecular genetic analyses to identify and characterize the proteins and their encoding genes corresponding to the 74- and 34- to 43-kDa major immunodominant antigens of P. insidiosum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms and antigen preparations.

The 22 clinical isolates of Pythium insidiosum used in this study and clinical details, including the form of pythiosis and the geographic origins of the patients for each isolate, are listed in Table 1 . The method of antigen preparation was that described previously (18). Briefly, P. insidiosum strain P1 was cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar for 3 days at 37°C. Ten small agar pieces, containing hyphal elements, from the growing culture were transferred to 100 ml of Sabouraud dextrose broth and shaken (150 rpm) for 10 days at 37°C. Merthiolate (0.02% [wt/vol]) was added to kill the cultures before they were filtered through a Durapore membrane filter (0.22-μm pore size; Millipore, County Cork, Ireland). The filtered broth containing phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; 0.1 mg/ml) and EDTA (0.3 mg/ml) is referred to as culture filtrate antigen (CFA). The retained hyphal mass was transferred to a mortar in the presence of 25 ml of cold sterile distilled water containing PMSF (0.1 mg/ml) and EDTA (0.3 mg/ml). The hyphal mass was ground on ice and centrifuged at 4,800 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant, referred to as soluble antigen from broken hyphae (SABH), was filtered through a Durapore membrane filter (0.22-μm pore). SABH and CFA were concentrated ∼80-fold using an Amicon Ultra 15 centrifugal filter (10,000 nominal-molecular-weight limit; Millipore, Bedford, MA). The concentrated preparations were stored at −20°C until use.

TABLE 1.

P. insidiosum isolates from Thai patients with pythiosis used in this study

| Clinical isolate | Geographic origin (province) | Form of infection | Reference | GenBank accession no.a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Bangkok | Artery | Personal collection | GU994090 |

| P2 | Lopburi | Artery | Personal collection | GU994091 |

| P3 | Chantaburi | Artery | Personal collection | GU994092 |

| P6 | Nan | Artery | CBS119452 | GU994093 |

| P7 | Ayuthaya | Artery | Personal collection | GU994094 |

| P9 | Lumpang | Artery | CBS119453 | GU994095 |

| P10 | NAb | Cut | CBS673.85 | GU994096 |

| P11 | Saraburi | Cut | Personal collection | GU994097 |

| P15 | Yasothon | Cornea | Personal collection | GU994098 |

| P16 | Saraburi | GIc | Personal collection | GU994099 |

| P17 | Chonburi | Cornea | Personal collection | GU994100 |

| P19 | NA | Cornea | Personal collection | GU994101 |

| P20 | NA | Cornea | Personal collection | GU994102 |

| P22 | Patomthani | Cornea | Personal collection | GU994103 |

| P24 | Supanburi | Artery | Personal collection | GU994104 |

| P25 | Nakornpatom | Artery | Personal collection | GU994105 |

| P27 | NA | Cornea | Personal collection | GU994106 |

| P28 | NA | Artery | Personal collection | GU994107 |

| P29 | NA | Artery | Personal collection | GU994108 |

| P30 | Rachaburi | Artery | Personal collection | GU994109 |

| P32 | NA | Cornea | Personal collection | GU994110 |

| P40 | Pichit | Artery | Personal collection | GU994111 |

Accession number of the putative exo-1,3-ß-glucanase partial gene sequence of each P. insidiosum isolate used in this study.

NA, not available.

GI, gastrointestinal tract.

Serum samples.

Sera from five patients with vascular pythiosis diagnosed by culture identification and serological tests (serum samples T1 to T5) and five healthy blood donors (serum samples C1 to C5) who came to the Blood Bank Division, Ramathibodi Hospital, were used for evaluating the immunoreactivities of the synthetic peptides in this study. All sera were stored at −20°C until use.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE and Western blotting analysis were performed according to the procedures described previously (18). Briefly, ∼15 μg of SABH or CFA was mixed with loading buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 25% glycerol, 2% SDS, 14.4 mM mercaptoethanol, 0.1% bromophenol blue), boiled for 5 min, and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 min. The proteins in the supernatant were separated at 100 V in an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (4% stacking gel, 12% separating gel) on a minigel apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Prestained SDS-PAGE molecular weight standards (Bio-Rad) were run in parallel.

For Western blot analysis, the separated antigens were electrotransferred from SDS-polyacrylamide gels to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad) for 1 h at 100 V. The membranes were blocked with 5% gelatin in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), pH 7.5, and incubated overnight at room temperature with pythiosis serum sample T1 diluted 1:1,000 with antibody buffer (Tris-buffered saline [TBS], pH 7.5, 0.05% Tween 20, 1% gelatin). The membranes were washed twice with washing buffer (TBS, pH 7.5, 0.05% Tween 20) and incubated at room temperature for 2 h with goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (heavy plus light chains) conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Bio-Rad) at a 1:3,000 dilution with antibody buffer. The membranes were washed with washing buffer three times. Signals were developed by adding a fresh mixture of 10 ml of 0.3% 4-chloro-1-naphthol in methanol and 50 ml of TBS with 30 μl of 30% H2O2. The reactions were stopped by immersing the membranes in distilled water. Membranes in which the color developed were immediately photographed.

Mass spectrometric analysis.

SABH and CFA protein bands corresponding to the 43- and 74-kDa immunodominant antigens, separated by one-dimension SDS-PAGE, were excised from a Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gel and cut into 1-mm pieces. Destaining, trypsin in-gel digestion, extraction, and peptide purification were performed using the protocol of Saveliev et al. (37). The peptides were subjected to analysis on a MDS SCIEX 4800 matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-tandem time of flight (MALDI-TOF/TOF) mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) at the Biotechnology Center, University of Wisconsin—Madison. Peptide mass fingerprints (PMFs) were generated and used to match theoretical trypsin-digested proteins in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database using the program MASCOT (37). Some peptide masses for generating de novo amino acid sequence tags by MALDI-TOF/TOF tandem MS/MS analysis were selected. The de novo amino acid sequence of each peptide was compared with the sequences in the NCBI nonredundant protein database (blastp) by BLAST analysis.

Genomic DNA extraction, PCR, and DNA sequencing.

Genomic DNA extraction was performed using the protocol of Pannanusorn et al. (31) or Vanittanakom et al. (43). The 1.1-kb region of the P. insidiosum ß-glucanase gene sequence was amplified by PCR using degenerate primers Pr1 (5′-ACNTTYGARCAYTGGCCNAT-3′) and Pr4 (5′-ARRTGCCARTAYTGRTTRAA-3′). Alternatively, primers Pr7 (5′-ACGTTCGAGCACTGGCCTAT-3′) and Pr10 (5′-AGGTGCCAGTACTGGTTGAA-3′) (which are subset primers of Pr1 and Pr4, respectively, that were derived from the sequence of the putative exo-1,3-ß-glucanase gene, EXO1, of Phytophthora infestans) were used to amplify the glucanase DNA sequences of some P. insidiosum isolates. The amplifications were carried out in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing 200 ng genomic DNA, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1 μM each primer, and 1 μl of Elongase DNA polymerase mixture (Invitrogen) in 1× Elongase buffer (ratio of buffer A/buffer B = 1:4). Amplifications were performed in a MyCycler thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) with the following cycling temperatures: denaturation at 94°C for 2.5 min for the first cycle and 30 s for subsequent cycles, annealing for 30 s at 40°C, and elongation for 1.5 min at 68°C for a total of 35 cycles, followed by a final extension for 10 min at 68°C. The PCR products were assessed for amount and size by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Direct sequencing of PCR products was performed using the BigDye Terminator (version 3.1) cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). Primers Pr1, Pr7, and Pr46 (5′-ACCTCATGTCCAAGAAGCTCAACG-3′) were used to obtain the forward sequences; and primers Pr4, Pr10, and Pr43 (5′-CGCGCATAAAGTCGAGCCAGAA-3′) were used for the reverse sequence. Automated sequencing was carried out using an ABI 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems), and the sequences were analyzed using the Applied Biosystems sequencing software.

Synthetic peptides and ELISA.

Synthetic peptides s74-1 (WTSIASTQPVGTTTFEHWPIR) and s74-2 (FLTLEEQCDWAFNQYWHLNR) (≥95% pure) were purchased from BioSynthesis Inc. (Lewisville, TX). Each peptide was dissolved in sterile distilled water. The s74-1 and s74-2 peptides were diluted to a final concentration of 0.1 μg/ml in 50 mM phosphate buffer with 0.6 M NaCl (pH 5.6) or 50 mM acetate buffer with 0.6 M NaCl (pH 2.6). Each peptide was used to coat a 96-well polystyrene plate (100 μl/well; Costar; Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY) at 4°C overnight. Unbound antigens were removed by four washes with washing buffer (0.1 M Tris-NaCl buffer with 0.1% Tween). Serum samples from pythiosis patients and blood donors were diluted 200-fold in 0.15 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2) with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (PBS-BSA) and added to wells in triplicate (100 μl/well), and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and washed four times. Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG Fcγ antibody (AffiniPure; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) was diluted 100,000-fold in PBS-BSA and added to each well (100 μl/well), and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After unbound conjugate antibody was washed four times, 100 μl of tetramethylbenzidine solution (galactomannan enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] kit; Bio-Rad) was added to each well. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl of 1.5 N H2SO4 to each well. The optical densities at 450 and 650 nm were measured with an ELISA reader (Behring Diagnostic).

Phylogenetic analysis.

The putative partial gene sequences of the exo-1,3-ß-glucanases of all P. insidiosum isolates (Table 1) were aligned by using the ClustalW program (11), and the alignments were manually edited. The phylogenetic tree of the P. insidiosum glucanase gene sequences and the P. infestans EXO1 sequence (set as the outgroup for rooting) was generated by the neighbor-joining (NJ) algorithm in the Phylip program and drawn using the Treeview program (30). The reliability of the inferred trees was tested using bootstrap resampling with 1,000 replicates (7).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All 22 P. insidiosum putative exo-1,3-β-glucanase sequences derived in this study have been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers GU994090 to GU994111 (Table 1).

RESULTS

Mass spectrometric analysis revealed that the 74-kDa antigen is ß-glucanase.

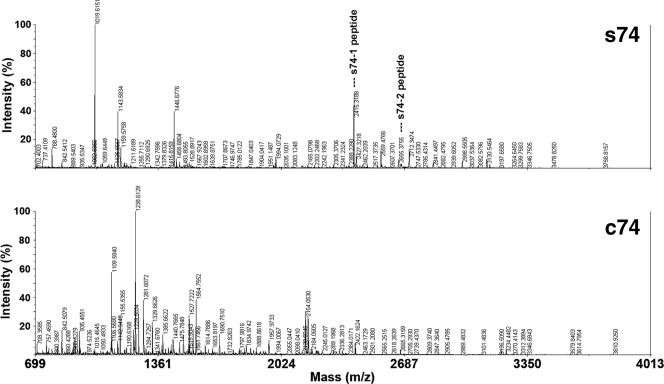

Two abundant antigenic proteins, namely, s74 and c74, corresponding to the 74-kDa major immunodominant bands of SABH and CFA, respectively (18), were excised from a one-dimension SDS-polyacrylamide gel to use for PMF by mass spectrometric analysis following trypsin digestion. Comparison of the PMFs of the s74 and c74 antigens did not reveal any significant spectrum similarity (Fig. 1). The peptide masses of each PMF were used to search for theoretical trypsin-digested proteins in the NCBI nonredundant database; and two peptide masses of the s74 antigen, 2,415.3 (relative intensity, 34%) and 2,671.4 (relative intensity, 3%), matched two peptides, WTSIASTQPVGTTTFEHWPIR (s74-1 peptide) and FLTLEEQCDWAFNQYWHLNR (s74-2 peptide), of a putative exo-1,3-ß-glucanase (EXO1) from the plant-pathogenic oomycete P. infestans (GenBank accession number AAM18483) (Fig. 1). The s74-1 and s74-2 peptides were matched to amino acid positions 278 to 298 and 634 to 653 of P. infestans EXO1, respectively. The de novo sequence of the s74-1 peptide determined by MS/MS analysis showed the same amino acid sequence predicted by the initial MS analysis. For the PMFs generated for the c74 protein, no peptide mass matched that of any protein in the NCBI database. Some of the c74 peptide masses with strong relative intensities (i.e., 1,109.6, 1,155.5, 1,238.6, 1,281.6, 1,564.8, and 2,154.1) underwent de novo sequencing by MS/MS analysis. The de novo amino acid sequences obtained (Table 2) were subjected to BLAST analysis of the sequences in the NCBI database, but none of them matched any protein. Another abundant protein, namely, s43, corresponding to the 43-kDa immunodominant band of SABH (18), was isolated from the SDS-polyacrylamide gel and was subjected to the MS and MS/MS analyses. Neither the PMF of this peptide nor the de novo sequences of selected peptide masses with strong intensity (i.e., 1,842.8, 1,859.8, and 2,153.0; Table 1) matched any protein in the NCBI database.

FIG. 1.

Peptide mass fingerprints of s74 and c74 immunodominant proteins of P. insidiosum after isolation from one-dimension SDS-polyacrylamide gels, in-gel tryptic digestion, and MS analysis. s74-1 and s74-2 were peptides (indicated by the names in the figure) of the s74 protein that matched a putative exo-1,3-ß-glucanase of Phytophthora infestans (EXO1).

TABLE 2.

Peptide mass, relative intensity, and BLAST search result for de novo amino acid sequences of selected peptide masses of s43, s74, and c74 immunodominant proteins

| Protein | Peptide mass | Relative intensity (%) | De novo amino acid sequence | BLAST search result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s74 | 2,415.3 | 34 | WTSIASTQPVGTTTFEHWPIR | Putative exo-1,3-ß-glucanase |

| c74 | 1,109.6 | 55 | QMGLNYNPR | No significant similarity found |

| c74 | 1,155.5 | 27 | QKAGVSMFDR | No significant similarity found |

| c74 | 1,238.6 | 97 | DIAPGMKGMMR | No significant similarity found |

| c74 | 1,281.6 | 36 | IYGLADASMKGR | No significant similarity found |

| c74 | 1,564.8 | 37 | EGDMNSATGAGMVHR | No significant similarity found |

| c74 | 2,154.1 | 25 | KLNVMSGGTTLVTNTAGGG | No significant similarity found |

| s43 | 1,842.8 | 16 | HVIMDDISDGTGKR | No significant similarity found |

| s43 | 1,859.8 | 12 | CGYVDKGMICGKR | No significant similarity found |

| s43 | 2,153.0 | >30 | MNLQGLGATLATANAHPMPAR | No significant similarity found |

Partial DNA sequence of the P. insidiosum ß-glucanase gene.

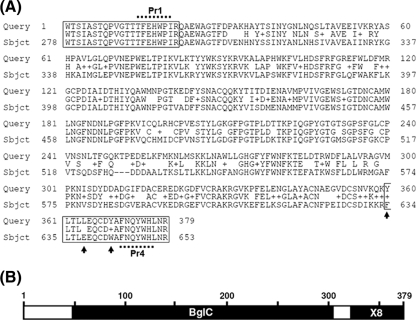

PCR primers were designed from within the reverse-translated amino acid sequences of the s74-1 and s74-2 peptides. Degenerate primer Pr1 (128-fold degeneracy) and Pr4 (64-fold degeneracy) were used to amplify the genomic DNA of P. insidiosum strains P17, P24, and P40 (Table 1), generating an intense 1.1-kb fragment. The DNA sequences of the 1.1-kb PCR product of each strain were analyzed by BLAST analysis of the sequences in the NCBI nucleotide database (blastn). The highest blastn match (identity, 71%; E value, <1e−146) was to a putative exo-1,3-ß-glucanase gene of P. infestans (EXO1; GenBank accession number AF494014). The deduced amino acid sequence (363 amino acids) of the partial putative exo-1,3-ß-glucanase gene of P. insidiosum amplified from strain P17 had in-frame translations with the s74-1 and s74-2 peptides (Fig. 2 A). The amino acid sequence deduced from the PCR product fused with the complete s74-1 and s74-2 peptide sequences (379 amino acids all together) was used for BLAST analysis against the sequences in the NCBI protein database (blastp), and the best match (identity, 73%; positivity, 83%; gap, 0.8%; E value, 8e−170) was an exo-1,3-ß-glucanase protein of P. infestans (EXO1; accession number AAM18483) (Fig. 2A). An NCBI conserved-domain database search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) revealed two conserved domains, BglC and the X8 superfamily (Fig. 2B). Similar results were observed for P. insidiosum strains P24 and P40.

FIG. 2.

Protein alignment and conserved domain of the putative glucanase of P. insidiosum. (A) Alignment of the deduced amino acid of the s74 partial protein of P. insidiosm (query; a 379-amino-acid long protein) and P. infestans EXO1 (subject; positions 278 to 653 of the 745-amino-acid long protein). Boxes at the beginning and at the end of the protein sequence indicate the locations of the s74-1 and s74-2 peptides of P. insidiosum that were predicted by MS analysis, respectively. Dotted lines at the beginning and at the end of the protein sequence indicate the positions of degenerate primers Pr1 and Pr4, respectively. In respect to the s74-2 peptide sequence of P. insidiosum, 3 deduced amino acids at positions 360, 364, and 369 (arrows) were different from the amino acids predicted by MS analysis. (B) Predicted conserved protein domains of the deduced amino acid sequence of the s74 partial protein gene of P. insidiosum.

Immunoreactivity of P. insidiosum ß-glucanase peptides.

Synthetic peptides s74-1 and s74-2 were each used to coat ELISA plates and tested against the serum samples from patients with pythiosis (samples T1 to T5) and controls (samples C1 to C5). Among the pythiosis sera, pythiosis serum samples T1 (hemagglutination [HA] titer [12] = 1:5,120) and T5 (HA titer = 1:40,960) gave remarkably high ELISA signals (1.2 and 0.8, respectively, for s74-1; 1.2 and 1.0, respectively, for s74-2), while pythiosis serum samples T2 (HA titer = 1:2,560), T3 (HA titer = 1:1,280), and T4 (HA titer = 1:1,280) gave weak to moderate ELISA signals (0.4, 0.3, and 0.3, respectively, for s74-1; 0.5, 0.4, and 0.3, respectively, for s74-2). In general, the s74-1 (Fig. 3 A) or the s74-2 (Fig. 3B) peptide gave similar ELISA signal patterns with the different serum samples.

FIG. 3.

Immunoreactivity of s74-1 (A) and s74-2 (B) peptides against pythiosis sera (samples T1 to T5) and control sera (samples C1 to C5) by ELISA. For the s74-1 peptide, the ELISA cutoff point (dashed line; the mean ELISA signal of the control sera plus 2 SDs) is 0.32, and the mean ELISA signals of the pythiosis and control sera are 0.48 (range, 0.26 to 1.17; SD, 0.39) and 0.15 (range, 0.07 to 0.27; SD, 0.09), respectively. For the s74-2 peptide, the ELISA cutoff point is 0.21 and the mean ELISA signal of the pythiosis and control sera are 0.57 (range, 0.33 to 1.22; SD, 0.39) and 0.09 (range, 0.05 to 0.18; SD, 0.06), respectively.

For the s74-1 peptide, the mean ELISA signal of the pythiosis sera was 0.48 (range, 0.26 to 1.17; standard deviation [SD], 0.39), while the mean ELISA signal of the control sera was 0.15 (range, 0.07 to 0.27; SD, 0.09). If a cutoff point of 0.32 (which equals the mean ELISA signal of the control sera plus 2 SDs of the mean) is set, 60% of the pythiosis sera had ELISA signals above this cutoff, but 100% of the control sera had signals below the cutoff (Fig. 3A). For the s74-2 peptide, the mean ELISA signal of the pythiosis sera was 0.57 (range, 0.33 to 1.22; SD, 0.39), while the mean ELISA signal of the control sera was 0.09 (range, 0.05 to 0.18; SD, 0.06). On the basis of the cutoff point of 0.21 (the mean ELISA signal of control sera plus 2 SDs), all pythiosis sera were clearly differentiated from all control sera (Fig. 3B).

Phylogenetic analysis of P. insidiosum ß-glucanase genetic sequences.

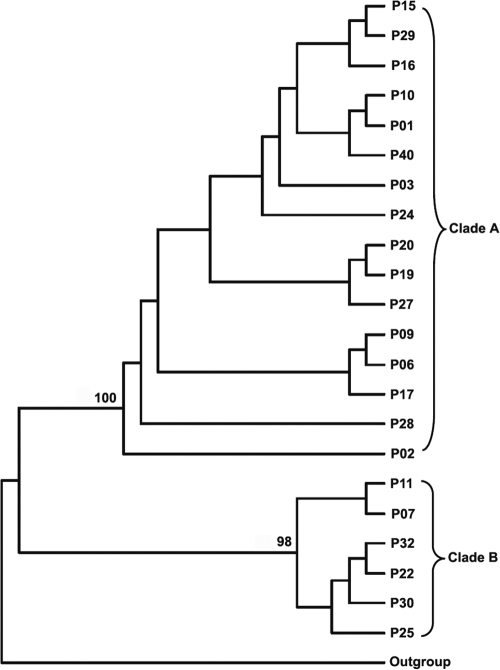

The ß-glucanase gene sequences of 22 P. insidiosum isolates from patients with different forms of pythiosis who lived in different regions of Thailand (Table 1) were successfully amplified and sequenced using primers Pr1 and Pr4 or primers Pr7 and Pr10. These sequences were analyzed for phylogenetic relatedness using the NJ algorithm (setting the P. infestans EXO1 gene as an outgroup for rooting). From this analysis, P. insidiosum can be divided into two phylogenetic groups, clade A and clade B, with 98% and 100% reliability, respectively (Fig. 4). The distributions of the forms of pythiosis and the geographic origins of the patients in the two clades were similar.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of 22 clinical isolates of P. insidiosum, based on partial putative exo-1,3-ß-glucanase DNA sequences, reveals that the organism can be divided into two clades, clade A (n = 16) and clade B (n = 6). P. infestans EXO1 is used as an outgroup for rooting.

DISCUSSION

Several proteins with immunodominant reactivity against pythiosis patient sera were analyzed by mass spectrometry of tryptic digests to determine their protein identities. These analyses included proteins corresponding to the 74- and 43-kDa antigens of P. insidiosum cytoplasmic proteins (SABH; s74 and s43 antigens) and the 74-kDa antigen of secreted proteins (CFA; c74 antigen) (18). The topologies of the PMFs of the s74 and c74 antigens were different (Fig. 1), suggesting that although these antigens coincidentally had the same molecular size (74 kDa) and are major immunodominant antigens, they were not the same protein. For the peptide masses of the s74 antigen, two matches were found by searching for theoretical trypsin-digested proteins in the NCBI nonredundant protein database. These two peptide masses of the s74 antigen, s74-1 and s74-2, had predicted amino acid compositions identical to those of the predicted tryptic peptides of EXO1 of P. infestans, an oomycete member in a genus closely related to Pythium. The s74-1 peptide was selected for de novo sequencing because from the s74 PMF, it had a stronger intensity than the s74-2 peptide (34% and 3%, respectively). The de novo sequence of the 74-1 peptide amino acid sequence perfectly matched that of P. infestans EXO1, confirming that the predicted amino acid sequence of this peptide determined by the MS analysis was correct, and thus, the identity of the s74 protein, a putative glucanase, was confirmed. Some of the strong-intensity peptide masses of c74 and s43 proteins (Table 2) were selected for de novo sequencing. None of these additional de novo sequences matched the sequence of any protein in the protein database; therefore, these peptides may be unique to P. insidiosum.

For P. infestans EXO1 (745 amino acids long), the sequence encompassing the s74-1 and s74-2 peptides and the region in between is predicted to be 376 amino acids, and the length of corresponding DNA sequence is predicted to be 1,128 bp long. This prediction is consistent with the fact that the degenerate primers (Pr1 and Pr4) designed from the s74-1 and s74-2 peptide sequences successfully amplified a 1.1-kb PCR product, and the DNA sequence significantly matched that of P. infestans EXO1 (data not shown). The amino acid sequence deduced from this P. insidiosum DNA sequence had high degrees of identity and similarity to the P. infestans EXO1 peptide over its entire length (Fig. 2A). Searches of NCBI conserved-domain databases revealed that the putative P. insidisoum glucanase had two predicted conserved domains, namely, BglC and X8 (Fig. 2B). These domains are found in proteins involved in carbohydrate transportation, metabolism, and binding. Three consecutive amino acids corresponding to amino acid positions 250 to 252 of the P. insidiosum glucanase were absent in the P. infestans EXO1, making this portion of P. infestans EXO1 a little shorter (Fig. 2A). In respect to the s74-2 peptide sequence derived from the MS analysis, there were 3 discrepant amino acids found in the P. insidiosum deduced amino acid sequences, at positions 360, 364, and 369 (indicated by arrows in Fig. 2A). In spite of this error in the sequence prediction by the MS analysis, the proteomic, molecular genetic, and bioinformatic evidence consistently supports the conclusion that the 74-kDa protein of P. insidiosum is an exo-1,3-ß-glucanase. Glucanases are an interesting group of hydrolytic enzymes that are present in many organisms, including fungi (2, 22, 33). Glucans are major cell wall components that give strength and rigidity to fungal cells, and fungal glucanase hydrolytic activity is necessary in order to remodel the cell wall for hyphal elongation or growth (2, 22, 33). Although putative glucanases have been identified in some oomycetes (8, 23), little is know about their biological and pathological roles. In the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans (21, 35), glucanases have roles in morphogenesis (hyphal formation and growth), pathogenesis (adhesion and hyphal invasion), and host immune responses (stimulation of host immunity).

Although the characterization of the glucanase of P. insidiosum began with a 74-kDa major immunodominant band in the Western blot analysis (18), we sought further evidence for its immunoreactivity. To provide a specific test for immune recognition, an ELISA was developed using either the s74-1 or s74-2 synthetic peptide of the glucanase. The mean ELISA signal for the pythiosis sera was higher than that of the control sera for both the s74-1 and the s74-2 peptides (3.2-fold and 6.3-fold higher, respectively). The ELISA results for individual pythiosis sera were higher than those for all of the control sera in 60% of the cases using the s74-1 peptide and 100% of the cases using the s74-2 peptide (Fig. 3). These results confirm the immunoreactivity of the P. insidiosum glucanase and indicate that the s74-2 peptide is more robustly immunoreactive than the s74-1 peptide in ELISAs. Furthermore, the high ELISA signals for serum samples T1 and T5 correlated with their high HA titers, while the low ELISA signals for serum samples T2, T3, and T4 correlated with the low HA titers of these sera (Fig. 3). Further optimizations of the ELISA by increasing the purity and the concentration of each peptide might improve the assay discrimination power, a factor necessary for development of a serodiagnostic test.

Use of the exo-1,3-ß-glucanase gene sequence of P. insidiosum for phylogenetic analysis revealed two separable groups (clades A and B) of P. insidiosum in Thailand (Fig. 4). This finding is consistent with previous rDNA sequence analyses that also showed two clades for P. insidiosum in Thailand (5, 40, 41). It is noteworthy that for both glucanase- and rDNA-based analyses, there is no correlation of the phylogenetic group with either the geographic distribution or the clinical presentation of pythiosis patients.

Because other oomycetes have ß-glucan as a major cell wall component (20), it is expected that P. insidiosum would as well. The discovery, in P. insidiosum, of a putative glucanase (a glucan-hydrolyzing enzyme, which may be necessary for cell wall remodeling in the fungi [33, 35]) further supports this possibility. The presence of ß-glucan in their cell wall could mean that the oomycetes would be sensitive to a new class of antifungal drugs, the echinocandins (i.e., caspofungin, anidulafungin, and micafungin), whose mechanism of antifungal action is to inhibit cell wall ß-glucan synthesis (1). However, in both in vivo and in vitro experiments, caspofungin failed to adequately control the growth of P. insidiosum (3, 32). The reason for this failure is unknown but could result from differences between the fungal and oomycete glucan synthases or from other differences, such as the uptake, binding, or metabolism of the drug.

In the present study, we have successfully used a proteomic approach to characterize a 74-kDa major immunoreactive antigen of P. insidiosum as a putative exo-1,3-ß-glucanase. Molecular genetic analysis showed that this protein was encoded by a gene sequence homologous to a P. infestans exo-1,3-ß-glucanase gene, EXO1. The P. insidiosum EXO1 DNA sequence can be classified into two phylogenetic groups. Because the s74-1 and s74-2 peptides, representing portions of the P. insidiosum 74-kDa glucanase, were strongly recognized by sera from patients with pythiosis (Fig. 3), they could be new antigenic targets in the development of serodiagnostic tests. The P. insidiosum 74-kDa glucanase could also be tested as a new vaccine candidate in an established animal model of pythiosis (36).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University (to T. Krajaejun), and the Thailand Research Fund (to T. Krajaejun) and a Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. Scholarship from the Thailand Research Fund (to A. Keeratijarut).

We are grateful to Pimpan Tadthong, Piriyaporn Chongtrakool, Piroon Mootsikapun, Angkana Chaiprasert, Nongnuch Vanittanakom, and Ariya Chindamporn for their help, suggestions, as well as material support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 March 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abuhammour, W., and E. Habte-Gaber. 2004. Newer antifungal agents. Indian J. Pediatr. 71:253-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams, D. J. 2004. Fungal cell wall chitinases and glucanases. Microbiology 150:2029-2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, T. A., A. M. Grooters, and G. L. Hosgood. 2008. In vitro susceptibility of Pythium insidiosum and a Lagenidium sp to itraconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole, terbinafine, caspofungin, and mefenoxam. Am. J. Vet. Res. 69:1463-1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, C. C., J. J. McClure, P. Triche, and C. Crowder. 1988. Use of immunohistochemical methods for diagnosis of equine pythiosis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 49:1866-1868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaiprasert, A., T. Krajaejun, S. Pannanusorn, C. Prariyachatigul, W. Wanachiwanawin, B. Sathapatayavongs, T. Juthayothin, N. Smittipat, N. Vanittanakom, and A. Chindamporn. 2009. Pythium insidiosum Thai isolates: molecular phylogenetic analysis. Asian Biomed. 3:623-633. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaiprasert, A., S. Samerpitak, W. Wanachiwanawin, and P. Thasnakorn. 1990. Induction of zoospore formation in Thai isolates of Pythium insidiosum. Mycoses 33:317-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaulin, E., M. A. Madoui, A. Bottin, C. Jacquet, C. Mathé, A. Couloux, P. Wincker, and B. Dumas. 2008. Transcriptome of Aphanomyces euteiches: new oomycete putative pathogenicity factors and metabolic pathways. PLoS One 3:e1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grooters, A. M., and M. K. Gee. 2002. Development of a nested polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection and identification of Pythium insidiosum. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 16:147-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grooters, A. M., B. S. Leise, M. K. Lopez, M. K. Gee, and K. L. O'Reilly. 2002. Development and evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the serodiagnosis of pythiosis in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 16:142-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins, D., J. Thompson, and T. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jindayok, T., S. Piromsontikorn, S. Srimuang, K. Khupulsup, and T. Krajaejun. 2009. Hemagglutination test for rapid serodiagnosis of human pythiosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:1047-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamoun, S. 2003. Molecular genetics of pathogenic oomycetes. Eukaryot. Cell 2:191-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keeling, P. J., G. Burger, D. G. Durnford, B. F. Lang, R. W. Lee, R. E. Pearlman, A. J. Roger, and M. W. Gray. 2005. The tree of eukaryotes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20:670-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keeratijarut, A., P. Karnsombut, R. Aroonroch, S. Srimuang, T. Sangruchi, L. Sansopha, P. Mootsikapun, N. Larbcharoensub, and T. Krajaejun. 2009. Evaluation of an in-house immunoperoxidase staining assay for histodiagnosis of human pythiosis. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 40:1298-1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krajaejun, T., S. Imkhieo, A. Intaramat, and K. Ratanabanangkoon. 2009. Development of an immunochromatographic test for rapid serodiagnosis of human pythiosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:506-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krajaejun, T., M. Kunakorn, S. Niemhom, P. Chongtrakool, and R. Pracharktam. 2002. Development and evaluation of an in-house enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for early diagnosis and monitoring of human pythiosis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 9:378-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krajaejun, T., M. Kunakorn, R. Pracharktam, P. Chongtrakool, B. Sathapatayavongs, A. Chaiprasert, N. Vanittanakom, A. Chindamporn, and P. Mootsikapun. 2006. Identification of a novel 74-kilodalton immunodominant antigen of Pythium insidiosum recognized by sera from human patients with pythiosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1674-1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krajaejun, T., B. Sathapatayavongs, R. Pracharktam, P. Nitiyanant, P. Leelachaikul, W. Wanachiwanawin, A. Chaiprasert, P. Assanasen, M. Saipetch, P. Mootsikapun, P. Chetchotisakd, A. Lekhakula, W. Mitarnun, S. Kalnauwakul, K. Supparatpinyo, R. Chaiwarith, S. Chiewchanvit, N. Tananuvat, S. Srisiri, C. Suankratay, W. Kulwichit, M. Wongsaisuwan, and S. Somkaew. 2006. Clinical and epidemiological analyses of human pythiosis in Thailand. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:569-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon-Chung, K. J. 1994. Phylogenetic spectrum of fungi that are pathogenic to humans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 19:S1-S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.La Valle, R., S. Sandini, M. J. Gomez, F. Mondello, G. Romagnoli, R. Nisini, and A. Cassone. 2000. Generation of a recombinant 65-kilodalton mannoprotein, a major antigen target of cell-mediated immune response to Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 68:6777-6784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin, K., B. M. McDougall, S. McIlroy, J. Chen, and R. J. Seviour. 2007. Biochemistry and molecular biology of exocellular fungal beta-(1,3)- and beta-(1,6)-glucanases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 31:168-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLeod, A., C. D. Smart, and W. E. Fry. 2003. Characterization of 1,3-beta-glucanase and 1,3;1,4-beta-glucanase genes from Phytophthora infestans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 38:250-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendoza, L., L. Ajello, and M. R. McGinnis. 1996. Infection caused by the oomycetous pathogen Pythium insidiosum. J. Mycol. Med. 6:151-164. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendoza, L., F. Hernandez, and L. Ajello. 1993. Life cycle of the human and animal oomycete pathogen Pythium insidiosum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2967-2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendoza, L., L. Kaufman, W. Mandy, and R. Glass. 1997. Serodiagnosis of human and animal pythiosis using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4:715-718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendoza, L., L. Kaufman, and P. G. Standard. 1986. Immunodiffusion test for diagnosing and monitoring pythiosis in horses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 23:813-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendoza, L., and J. C. Newton. 2005. Immunology and immunotherapy of the infections caused by Pythium insidiosum. Med. Mycol. 43:477-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendoza, L., and J. Prendas. 1988. A method to obtain rapid zoosporogenesis of Pythium insidiosum. Mycopathologia 104:59-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page, R. D. M. 1996. TREEVIEW: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 12:357-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pannanusorn, S., A. Chaiprasert, C. Prariyachatigul, T. Krajaejun, N. Vanittanakom, A. Chindamporn, W. Wanachiwanawin, and B. Satapatayavong. 2007. Random amplified polymorphic DNA typing and phylogeny of Pythium insidiosum clinical isolates in Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 38:383-391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereira, D. I., J. M. Santurio, S. H. Alves, J. S. Argenta, L. Pötter, A. Spanamberg, and L. Ferreiro. 2007. Caspofungin in vitro and in vivo activity against Brazilian Pythium insidiosum strains isolated from animals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60:1168-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitson, S. M., R. J. Seviour, and B. M. McDougall. 1993. Noncellulolytic fungal beta-glucanases: their physiology and regulation. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 15:178-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pracharktam, R., P. Changtrakool, B. Sathapatayavongs, P. Jayanetra, and L. Ajello. 1991. Immunodiffusion test for diagnosis and monitoring of human pythiosis insidiosi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:2661-2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandini, S., R. La Valle, F. De Bernardis, C. Macrì, and A. Cassone. 2007. The 65 kDa mannoprotein gene of Candida albicans encodes a putative beta-glucanase adhesion required for hyphal morphogenesis and experimental pathogenicity. Cell. Microbiol. 9:1223-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santurio, J. M., A. T. Leal, A. B. Leal, R. Festugatto, I. Lubeck, E. S. Sallis, M. V. Copetti, S. H. Alves, and L. Ferreiro. 2003. Three types of immunotherapics against pythiosis insidiosi developed and evaluated. Vaccine 21:2535-2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saveliev, S., D. Simpson, W. Daily, C. Woodroofe, D. Klaubert, G. Sabat, R. Bulliet, and K. V. Wood. 2008. Improve protein analysis with the new, mass spectrometry-compatible ProteasMAX™ surfactant. Promega Notes 99:3-7. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schlosser, E., and D. Gottlieb. 1966. Sterols and the sensitivity of Pythium species to filipin. J. Bacteriol. 91:1080-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schurko, A. M., L. Mendoza, A. W. de Cock, J. E. Bedard, and G. R. Klassen. 2004. Development of a species-specific probe for Pythium insidiosum and the diagnosis of pythiosis, J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2411-2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schurko, A. M., L. Mendoza, C. A. Lévesque, N. L. Désaulniers, A. W. de Cock, and G. R. Klassen. 2003. A molecular phylogeny of Pythium insidiosum. Mycol. Res. 107:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Supabandhu, J., M. C. Fisher, L. Mendoza, and N. Vanittanakom. 2008. Isolation and identification of the human pathogen Pythium insidiosum from environmental samples collected in Thai agricultural areas. Med. Mycol. 46:41-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Supabandhu, J., P. Vanittanakom, K. Laohapensang, and N. Vanittanakom. 2009. Application of immunoblot assay for rapid diagnosis of human pythiosis. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 92:1063-1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vanittanakom, N., J. Supabandhu, C. Khamwan, J. Praparattanapan, S. Thirach, N. Prasertwitayakij, W. Louthrenoo, S. Chiewchanvit, and N. Tananuvat. 2004. Identification of emerging human-pathogenic Pythium insidiosum by serological and molecular assay-based methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3970-3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wanachiwanawin, W., L. Mendoza, S. Visuthisakchai, P. Mutsikapan, B. Sathapatayavongs, A. Chaiprasert, P. Suwanagool, W. Manuskiatti, C. Ruangsetakit, and L. Ajello. 2004. Efficacy of immunotherapy using antigens of Pythium insidiosum in the treatment of vascular pythiosis in humans. Vaccine 22:3613-3621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]