Abstract

The opportunistic human pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus is a major cause of fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. Innate immunity plays an important role in the defense against infections. The complement system represents an essential part of the innate immune system. This cascade system is activated on the surface of A. fumigatus conidia and hyphae and enhances phagocytosis of conidia. A. fumigatus conidia but not hyphae bind to their surface host complement regulators factor H, FHL-1, and CFHR1, which control complement activation. Here, we show that A. fumigatus hyphae possess an additional endogenous activity to control complement activation. A. fumigatus culture supernatant efficiently cleaved complement components C3, C4, C5, and C1q as well as immunoglobulin G. Secretome analysis and protease inhibitor studies identified the secreted alkaline protease Alp1, which is present in large amounts in the culture supernatant, as the central molecule responsible for this cleavage. An alp1 deletion strain was generated, and the culture supernatant possessed minimal complement-degrading activity. Moreover, protein extract derived from an Escherichia coli strain overproducing Alp1 cleaved C3b, C4b, and C5. Thus, the protease Alp1 is responsible for the observed cleavage and degrades a broad range of different substrates. In summary, we identified a novel mechanism in A. fumigatus that contributes to evasion from the host complement attack.

Aspergillus fumigatus is the most important airborne fungal pathogen. The frequency of invasive mycoses due to this opportunistic fungal pathogen has increased significantly during the last 2 decades (reviewed in references 7 and 42). In healthy individuals, A. fumigatus conidia are inhaled but the establishment of disease is prevented by the host immune system. Inhaled A. fumigatus conidia are immediately confronted with the host complement system and phagocytic cells. The complement system is activated on the conidial and hyphal surface (26), and this activation results in the cleavage of C3. Cleavage products of this central component of the complement cascade act as opsonins on the surfaces of pathogens and enhance phagocytosis by neutrophils, macrophages, and eosinophils (69). Opsonization with complement proteins is important for phagocytosis of A. fumigatus conidia, the key process in the defense against this pathogen (59).

Activation of the complement system occurs via three pathways: the alternative pathway (AP), the lectin pathway, and the classical pathway. The AP is activated on microbial surfaces and plays a pivotal role in the clearance of microorganisms (70). Progression of the cascade leads to generation of a C5 convertase, which produces inflammatory C5a anaphylatoxins, and also to the formation of terminal complement complexes (TCC), which can form membrane attack complexes (MAC) and hence pores on target surfaces. C3b surface deposition and MAC formation are important for clearance of bacteria but appear to play a minor role in the defense against fungi. The complement activation system is controlled by fluid-phase and cell surface-bound regulators. We and others showed before (2, 62) that A. fumigatus conidia bind factor H (the central human regulator of the AP), FHL-1, and CFHR1. Factor H acts as a cofactor for the plasma serine protease factor I, which mediates the cleavage of C3b (21, 35, 41). This blocks C3 convertase formation and leads to downregulation or termination of the complement cascade. In contrast to conidia, A. fumigatus hyphae do not bind factor H (2). Instead, they activate complement on their surface (26). Until now a single, nonprotein activity in culture supernatant that inhibits opsonization of the fungal surface by complement proteins has been described (65). The nature of this molecule has not been discovered yet. A. fumigatus inhibition of complement activation is important, since activation of the complement cascade causes toxic and damaging effector functions. Although hyphae are too big to become phagocytosed by macrophages, attraction and activation of neutrophils by C3a and C5a still lead to the destruction of hyphae. Therefore, here we analyzed whether A. fumigatus hyphae use additional strategies to interfere with the human complement system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal and bacterial strains.

The ΔakuBKU80 strain is an A. fumigatus strain deficient in nonhomologous end joining (9). The Δalp1 strain, with a deletion of the alp1 gene was derived by transformation of the ΔakuBKU80 strain with a knockout DNA fragment consisting of left and right flanking regions of the alp1 gene and the pyrithiamine resistance cassette as a dominant selection marker. Reconstitution of the Δalp1 mutant strain with the alp1 gene was performed with a plasmid containing the alp1 gene with its promoter and the hygromycin resistance cassette. For transformation of Escherichia coli, strain DH5α (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) or BL21(DE3) (16) was used, as stated. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with 100 μg per ml of ampicillin when required.

Standard molecular biological techniques and oligonucleotides.

Standard techniques for the manipulation of DNA were carried out as described previously (52). Plasmid DNA used for transformation of A. fumigatus was prepared using columns from Peqlab (Erlangen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Chromosomal DNA of A. fumigatus was prepared using the fungal DNA mini kit (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany). For Southern blot analysis, 10 μg of chromosomal DNA of A. fumigatus was cut with NcoI. DNA fragments were separated on a 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel and blotted onto a Hybond N+ nylon membrane (GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany). Labeling of the DNA probe was performed using the PCR digoxigenin (DIG) labeling mix (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). For hybridization and detection of DNA-DNA hybrids, the DIG Easy Hyb and the CDP-Star ready-to-use kit (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Generation of recombinant plasmids.

Left and right flanking regions (1 kb each) of the A. fumigatus alp1 gene were amplified from A. fumigatus chromosomal DNA by PCR using Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Frankfurt, Germany) and the oligonucleotides Alp_LB_for (ATTGCGGCCGCGTGCTCGAATCAGTGC), Alp_LB_rev (ATTGGCCTGAGTGGCCGCGCAGACTCTGACAAGAC), alp_RB_for (ATTGGCCATCTAGGCCCTGCGCAGGGCGAGTC) and alp_RB_rev (CAAACAGGCACCTACGTG), encoding NotI and SfiI sites (underlined), respectively. Both right and left flanking regions were cloned into pCR2.1 vectors, giving pCR2.1_alp1_RB and pCR2.1_alp1_LB, respectively. The orientation of the alp1 right flanking region in the pCR2.1 vector was checked, and a plasmid carrying the SfiI restriction site next to the NotI site of the pCR2.1 vector was used. The plasmids pCR2.1_alp1_RB and pCR2.1_alp1_LB were digested with NotI and SfiI. Plasmid pALptrA, containing the pyrithiamine resistance cassette, was cut with SfiI. The resulting DNA fragments, i.e., alp1_LB and the ptrA cassette, as well as the opened vector pCR2.1_alp1_RB, were gel purified and ligated. The resulting plasmid was designated pCR2.1_Dalp_ptrA. For transformation of A. fumigatus, this plasmid was digested with XhoI to excise the deletion construct consisting of the pyrithiamine resistance cassette flanked by left and right flanking regions of alp1. The plasmid for reconstitution of the alp1 gene in the Δalp1 strain was constructed as follows. alp1, including the 1-kb promoter region, was amplified by PCR using Phusion DNA polymerase with primers alp_RB_for_Bam (GGATCCGAGTCTTACCAGATGGATGGTGG) and alp_RB_rev_Bam (GGATCCCAGATACATACCATCCAAACCC). The DNA fragment was subcloned into a pJET1.2/blunt vector (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany) and excised from the backbone by restriction with BamHI. The DNA fragment was ligated into the BamHI-restricted vector pUChph, which contains the hygromycin resistance cassette. The resulting plasmid, pUChph_alp1+P, was used for transformation.

Transformation of A. fumigatus.

Transformation of A. fumigatus was carried out using protoplasts as described previously (66). When selection for pyrithiamine resistance was applied, 0.1 mg pyrithiamine (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) per liter was added to the agar plates. When clones were selected for hygromycin resistance, the agar plates were supplemented with 240 μg/ml hygromycin (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

A. fumigatus strains and growth conditions.

A. fumigatus wild-type ΔakuBKU80 strain (referred to as wild type below), the Δalp1 mutant strain, and the Δalp1C reconstituted strain were cultivated on Aspergillus minimal medium (AMM) agar plates with 1% (wt/vol) glucose at 37°C for 4 days. AMM consisted of 6 g/liter NaNO3, 1.52 g/liter KH2PO4, 0.52 g/liter KCl, 0.05% (wt/vol) MgSO4, and 1 μl/ml trace element solution (pH 6.5). The trace element solution consisted of 1 g FeSO4·7H2O, 8.8 g ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.4 g CuSO4·5H2O, 0.15 g MnSO4·4H2O, 0.1 g NaB4O7 ·10H2O, 0.05 g (NH4)6Mo7O24·4 H2O, and double-distilled water (ddH2O) to 1,000 ml. Conidia were harvested in sterile water. For protease assays, 100 ml medium was inoculated with 1 × 108 conidia. The medium was either AMM, AMM lacking a nitrogen and carbon source (AMM−N) and supplemented with 10 mM glucose and 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA), AMM−N with 1% (wt/vol) BSA, or AMM−N supplemented with 10 mM glucose and 0.4% (wt/vol) elastin. The cultures were incubated for 1 to 7 days with or without rotation at 37°C. The other medium used was AMM−N supplemented with 2% (vol/vol) normal human serum (NHS) and 5 mM glucose. Fifty milliliters of AMM was inoculated with 1 × 106 conidia/ml and incubated at 37°C with rotation for 72 h for dry weight determination. Elastase secretion was visualized by growing A. fumigatus wild-type, Δalp1, and Δalp1C strains on agar plates containing 0.2% (wt/vol) elastin (Elastin Products Company, Owensville, MO), 0.01% (wt/vol) yeast extract, 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, and 1.5% (wt/vol) agar.

Serum, antibodies, proteins, and protease inhibitors.

NHS was obtained from healthy human donors and stored at −20°C until used. EDTA was added at a concentration of 10 mM (NHS-EDTA). Antibodies used in experiments were polyclonal goat anti-factor H antiserum, polyclonal goat anti-C1q antiserum, polyclonal goat anti-C3 antiserum, polyclonal goat anti-C4 antiserum, polyclonal goat anti-C5 antiserum, and polyclonal goat anti-C4BP antiserum (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated rabbit anti-goat antiserum was obtained from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark). HRP-coupled anti-human IgG antiserum was from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany). Factor H, factor I, and C3b were purchased from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany).

Cofactor assay and complement degradation assays.

Cofactor activity assay of surface-attached regulators was performed as described previously (2). Conidia (2 × 109) either were washed five times with binding buffer or were used directly without further washing steps or after heat inactivation for 10 min at 95°C. Conidia were resuspended in 150 μl binding buffer and were incubated with purified factor H (100 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. Conidia were washed, and C3b (2 μg) and factor I (1 μg) or C3b alone was added. Conidia were incubated for 60 min at 37°C on a shaker. The samples were centrifuged and the supernatants analyzed by Western blotting.

Complement degradation assays were carried out as follows. Three milliliters of culture supernatant of 1- to 7-day-old A. fumigatus cultures was filtered through an 0.8-μm filter to separate conidia and hyphae from the sample. In order to determine the class of the protease responsible for the observed cleavage, 1.56 μl EDTA (0.5 M), 0.15 μl leupeptin (1 mg/ml), 0.15 μl pepstatin, 7 μl aprotinin (5 mg/ml), 1.5 μl phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (1 mg/ml), or 0.5 μl chymostatin (20 mg/ml) was added to the culture supernatant prior to incubation with complement proteins. Three microliters of 1:10 diluted purified C3b, purified factor H, or NHS-EDTA was added to 150 μl filtered culture supernatant. The solution was incubated at 37°C for 60 min. Samples were subjected to reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Western blotting.

Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and cleavage of complement proteins C3, C4, C5, C1q, C4BP, and factor H, as well as IgG, was detected by Western blotting. The membranes were blocked with 2.5% (wt/vol) BSA-phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature and were subsequently incubated with polyclonal goat antiserum specific for C3, C4, C5, C1q, C4BP, or factor H (dilution of 1:1,000 in 2.5% [wt/vol] BSA-PBS-0.1% [vol/vol] Tween 20) for 120 min at room temperature. After five washing steps with PBS-0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20, HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-goat antiserum was added at a dilution of 1:5,000 and the membranes were incubated at room temperature for 60 min. For detection of IgG, membranes were incubated with HRP-coupled human IgG antiserum (dilution of 1:1,000 in 2.5% [wt/vol] BSA-PBS with 0.1% [vol/vol] Tween 20) for 120 min. After five washing steps with PBS-0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20, the proteins were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Applichem, Darmstadt, Germany).

Azocasein assay.

In order to measure the proteolytic activity of culture supernatant, 100 μl culture supernatant was incubated with an azocasein solution (5 mg azocasein in 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.2 M NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.05% [wt/vol] Brij 35) for 90 min at 37°C (10). The reaction was stopped by addition of 150 μl of 20% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid (TCA). After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 8 min and 500 μl of each supernatant was added to 500 μl 1 M NaOH. Absorbance was measured at 436 nm.

Secretome analysis.

Two 500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 150 ml AMM each were inoculated with 1 × 108 wild-type conidia and were incubated for 50 h at 37°C with rotation. The cultures were filtered over Miracloth. Ten milliliters of 100% (wt/vol) TCA was added to 100 ml supernatant of each culture, and the mixtures were incubated at 4°C to complete precipitation. The samples were centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 30 min. The pellets were washed with 1 ml acetone. After evaporation of all residual acetone, 150 μl lysis buffer were added to each sample. The lysis buffer (23) contained 7 M urea, 3 M thiourea, 1% (wt/vol) 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), 1% (vol/vol) Zwittergent, 0.8% (vol/vol) ampholyte, and 40 mM Tris. For protein solubilization, samples were incubated for 10 min in an ultrasonic bath. The protein concentration was measured as described previously (6). Fifty micrograms of protein sample was loaded on each strip by rehydration loading. Seven-centimeter strips with a pI range of 3 to 11 (GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany) were used. Focusing was carried out according to the GE Healthcare guidelines. Prior to second-dimension separation, strips were equilibrated for 15 min in equilibration buffer containing 1% (wt/vol) dithiothreitol (DTT) and subsequently for 15 min in buffer containing 2.5% (wt/vol) iodoacetamide. Second-dimension separation was performed on 12% acrylamide-Tris minigels. After fixation in 7% (vol/vol) acetic acid-30% (vol/vol) methanol for 1 h, gels were stained with colloidal Coomassie blue as described previously (38). Spot detection and analysis were performed with Delta2D software (Decodon, Greifswald, Germany). After excision of protein spots, the tryptic digest was carried out by in-gel digestion modified as described previously (55). Proteins were identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF)/TOF analysis in reflective mode (Bruker Daltics, Germany). Mass spectra were analyzed, and searching was performed using the NCBI Mascot server (MASCOT 2.1.03; Matrix Science, United Kingdom). Hits were regarded as significant with a Mascot score of 0.05.

Overproduction of the Alp1 protease.

AfAlp1 cDNA encoding a truncated Alp1 protein that lacks the 20 amino acids spanning the secretion signal (ΔN20Alp1-cDNA) was synthesized from A. fumigatus mRNA with the gene-specific primer pair AfAlp1tr_f/AfAlp1tr_r (5′ACTGGGATCCGCGCCTGTCCAGGAAACTCGTCGTGC3′/5′ACTGAAGCTTTTAAGCATTGCCATTGTAGGCTAGC3′) by using the BioScript one-step reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) kit from Bioline (Luckenwalde, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The ΔN20Alp1-cDNA was cloned into the BamHI-HindIII site of plasmid pMalC2TEVHapC (16) to give the plasmid pMalC2TEVΔN20Alp1. After transformation of E. coli strain BL21(DE3), the recombinant ΔN20Alp1 protein was overproduced by autoinduction as described elsewhere (16).

Animal experiments.

Female specific-pathogen-free outbred CD-1 mice 5 weeks of age (18 to 22 g; Charles River, Germany) were used for all experiments. The animals were housed in groups of five and cared for in accordance with the principles outlined in the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes. All animal experiments were in compliance with the German animal protection law and were approved by the responsible Federal State authority and ethics committee. Survival experiments following intranasal challenge were carried out as described previously (17). Briefly, mice were immunosuppressed by intraperitoneal injection of cortisone acetate (25 mg/mouse; Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) on days −3 and 0. On day 0 the mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg; Inresa Arzneimittel GmbH, Freiburg, Germany) and xylazine (2 mg/kg; Bayer Vital GmbH, Leverkusen, Germany) and infected intranasally with conidial suspensions containing 1 × 105 conidia in 20 μl PBS. Survival was monitored for 14 days. Immunosuppressed mice inoculated with PBS served as sham-infected controls in all experiments. Mice were examined clinically at least twice daily and weighed individually every day. Animals were considered moribund and sacrificed humanely when they showed rapid weight loss (>20% of body weight at the time of infection), severe dyspnoea, decreased body temperature, or other signs of serious illness.

RESULTS

Complement factor C3b is cleaved by an A. fumigatus endogenous activity.

A. fumigatus conidia bind the human complement regulators factor H, CFHR1, and FHL-1. The bound regulators are active and act as cofactors in the factor I-mediated cleavage of C3b. This effect was observed on washed conidia (Fig. 1A, lane 2). However, when conidia were subjected to this test without washing steps, a different cleavage pattern was observed (Fig. 1A, lane 3). C3b cleavage fragments were smaller than 43 kDa, and cleavage occurred without addition of factor H and factor I. C3b remained intact when conidia were heat inactivated prior to incubation with C3b (Fig. 1A, lane 4). These data suggested the presence of a spore-bound protease or of a mycelial protease that cleaves human C3b.

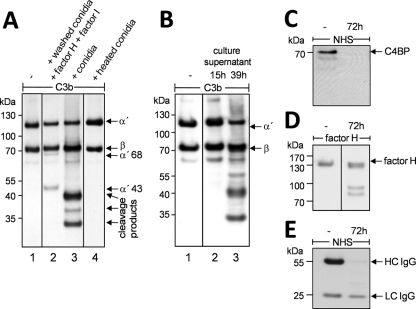

FIG. 1.

Degradation of complement components by A. fumigatus. (A) C3b inactivation on human host tissues is mediated by the human serine protease factor I in conjunction with the cofactor factor H. The degradation products of the α chain (115 kDa) of C3b are 68 kDa and 43 kDa in size (lane 2). When C3b was incubated together with A. fumigatus conidia, C3b was degraded even in the absence of factor I and factor H (lane 3). Incubation of C3b with PBS (lane 1) or heat-inactivated spores (lane 4) left C3b intact. (B) Degradation of C3b by culture supernatant. Samples of culture supernatant were taken after 15 h and 39 h of cultivation of A. fumigatus and were incubated with C3b. Degradation of C3b was analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Degradation products were visible only after incubation in the older culture supernatant (lane 3). (C to E) Degradation of complement regulators and IgG. Culture supernatant of a nonshaking culture incubated for 72 h was incubated with NHS or purified factor H. In controls (−), NHS or factor H was incubated with PBS instead of culture supernatant. Detection of cleavage fragments was performed with polyclonal antiserum directed against C4BP, IgG, or factor H. C4BP (C) and the heavy chains of IgG (E) were absent after incubation with culture supernatant. Factor H (D) was also cleaved but was still detectable.

To test whether the proteolytic activity was derived from spores or mycelia, culture supernatant of A. fumigatus was analyzed for C3b-degrading activity. Culture supernatants of 15- and 39-h-old culture were filtered and subsequently incubated with purified C3b for 30 min. Cleavage of C3b was visualized by Western blotting. In 15-h-old culture supernatant no degradation of C3b occurred, whereas in 39-h-old culture supernatant C3b was efficiently cleaved (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 3). Thus, the degrading activity was likely due to an A. fumigatus secreted protease. To investigate whether this activity specifically cleaves C3b or has a broader activity, the degradation of the complement regulators factor H and C4BP as well as immunoglobulin G was analyzed. Western blotting showed that C4BP was completely degraded by culture supernatant (Fig. 1C) and that factor H was cleaved but still detectable (Fig. 1D). Culture supernatant also cleaved the heavy chain of IgG. This is important for the initiation of the classical pathway and for binding of C1q as well as Fcγ-mediated phagocytosis (Fig. 1E). Thus, cleavage was not limited to C3b. Also, the complement regulators factor H, C4BP, and IgG were efficiently cleaved by culture supernatant of A. fumigatus.

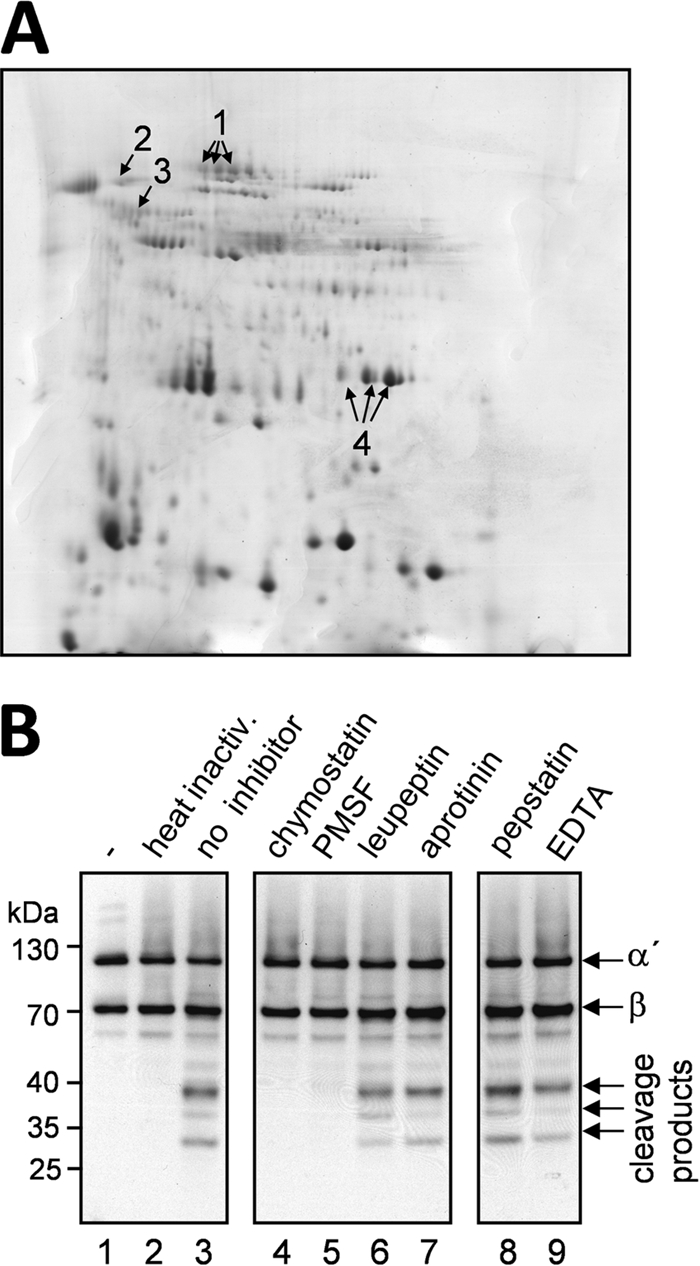

Identification of the C3b-degrading activity of A. fumigatus.

In order to investigate which proteases are secreted during growth in AMM, two-dimensional (2D) gel analysis of the culture supernatant was performed. Culture supernatant was filtered, precipitated, and separated by 2D gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2A). Mass spectrometry analysis of all visible protein spots revealed four secreted proteases which are present during growth in AMM (Fig. 2A, arrows 1 to 4), i.e., a secreted dipeptidyl peptidase (arrow 1), the aspartic type endoprotease AP3 (arrow 2), the aminopeptidase Y (arrow 3), and the alkaline serine protease Alp1 (arrow 4). The last protease was present in large amounts and was found more than once in a row of protein spots, possibly representing differently modified Alp1.

FIG. 2.

Secretome analysis and protease inhibitor studies. (A) Secretome analysis. Proteins in the culture supernatant of a 50-h-old A. fumigatus culture grown in AMM were precipitated with TCA and separated by 2D gel electrophoresis, and all detectable protein spots were subjected to mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. All spots representing proteases are marked with arrows. Arrow 1, secreted dipeptidyl peptidase; arrow 2, aspartic type endoprotease AP3; arrow 3, aminopeptidase Y; arrow 4, alkaline serine protease Alp1. (B) Protease inhibitor studies. Supernatant of a 39-h-old culture of A. fumigatus was incubated with different protease inhibitors prior to incubation with purified C3b. Addition of chymostatin, PMSF, leupeptin, or aprotinin should inhibit serine proteases (lanes 4 to 7). Incubation of supernatant with pepstatin (lane 8) and EDTA (lane 9) should block aspartic acid proteases and metalloproteases, respectively. C3b incubated with PBS (lane 1), with heat-inactivated culture supernatant (lane 2), and with untreated culture supernatant (lane 3) served as controls. Samples were subjected to reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis for the detection of C3b.

Since only four proteases, each belonging to a different protease class, were secreted under the incubation conditions used, protease inhibitor studies were carried out to identify the protease class responsible for C3b degradation. Culture supernatant was treated with protease inhibitors prior to incubation with C3b, and the cleavage pattern was studied by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2B). Pepstatin was added to inhibit aspartic proteases; EDTA was added to inhibit metalloproteases; and leupeptin, aprotinin, PMSF, and chymostatin were added to inhibit serine proteases. Of these protease inhibitors, PMSF and chymostatin inhibited the degradation of C3b by culture supernatant. This inhibition is characteristic of a serine protease with chymotrypsin-like activity. With Alp1, a single protease with these characteristics was present in the culture supernatant.

Absence of C3b degradation in Δalp1 strain culture supernatant.

To elucidate whether Alp1 was the protease responsible for the cleavage of C3b, an A. fumigatus alp1 deletion strain was generated (data not shown). Proteolytic activity present in supernatants of wild-type, Δalp1, and Δalp1C cultures grown in AMM was quantified by cleavage of the chromogenic substrate azocasein. When casein-degrading enzymes are present, the azo dye is released and cannot be precipitated with trichloric acid. This results in an increase of absorbance at 436 nm. Proteolytic activity was detectable in wild-type and Δalp1C supernatants (Fig. 3A). It increased with the age of the culture and was higher after 120 h than after 72 h of incubation (Fig. 3A, bars 1 and 3). No proteolytic activity was detectable in the presence of the inhibitor chymostatin (Fig. 3A, bars 2 and 4). The Δalp1 supernatant showed almost no proteolytic activity (Fig. 3A, bars 5 to 8). Thus, the major proteolytic activity was absent in the Δalp1 strain.

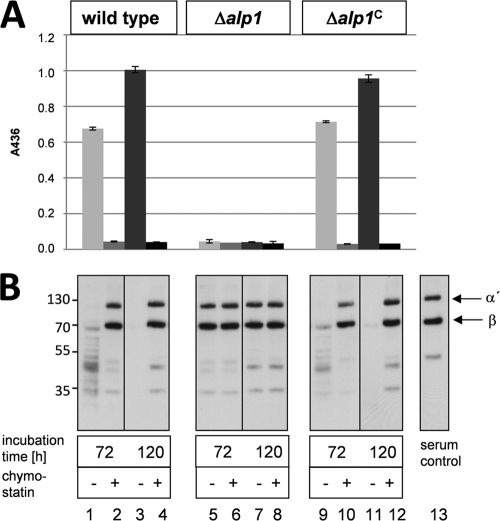

FIG. 3.

Protease activity and C3b degradation after growth in AMM. The wild-type, Δalp1, and Δalp1C strains were grown for 72 h and 120 h in AMM. Samples of the culture supernatants were either assayed directly or preincubated with the protease inhibitor chymostatin. (A) The proteolytic activities of supernatants of all cultures were measured with an azocasein assay. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) C3b degradation by culture supernatants was analyzed by Western blot analysis.

Culture supernatants of wild-type, Δalp1, and Δalp1C cultures were also tested for C3b degradation activity at 72 h and 120 h of incubation (Fig. 3B). C3b was added to filtered wild-type, Δalp1, and Δalp1C culture supernatants. Both the α′ and β chains of C3b were completely degraded by wild-type and Δalp1C supernatants. Addition of the inhibitor chymostatin to the culture supernatant inhibited C3b degradation (Fig. 3B, lanes 2, 4, 10, and 12). Culture supernatant of the Δalp1 mutant strain did not cleave C3b. Both chains remained intact even without the addition of chymostatin (Fig. 3B, lanes 5 to 8). Two faint low-molecular-weight bands were present in wild-type and Δalp1C supernatants after chymostatin treatment as well as in Δalp1 supernatant, indicating a minor residual complement-degrading activity in addition to Alp1. These results identify the A. fumigatus protease Alp1 as the major protease responsible for the degradation of C3b under these conditions.

The Alp1 protease cleaves C3b, C4b, and C5 in vitro.

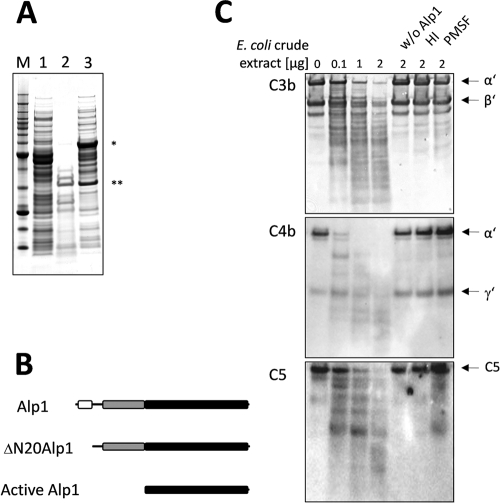

To further provide evidence that Alp1 is able to cleave the immune regulators, we overproduced the truncated protein ΔN20Alp1 in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. The Alp1 protein fused to the maltose binding protein (MPB) was autocatalytically processed during heterologous overproduction by cleaving off the MBP together with a probable peptidase inhibitor sequence (Fig. 4A and B). The processed and active Alp1 version was identified by mass spectrometry and showed a molecular mass of 32 kDa in SDS-PAGE. These results are in accordance with an in silico analysis which was carried out with the search tool at the Pfam database (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/search). The analysis revealed that Alp1 consists of two functional domains. The first domain shows similarity to the peptidase inhibitor I9 protein family (24, 31). This domain is predicted to act as both a temporary inhibitor and a molecular chaperone. Thus, it might facilitate the folding of the nascent protein. The second domain is predicted to encode a peptidase S8 of the subtilase family (48).

FIG. 4.

Presence of active ΔN20Alp1 in E. coli crude extract and cleavage of C3b, C4b, and C5 in vitro. (A) SDS-PAGE demonstrating the autocatalytic activation of MBP-fused ΔN20Alp1 during heterologous expression in E. coli BL21(DE3). Mass spectrometry analysis revealed the cleavage of an N-terminal peptidase inhibitor sequence (*, MBP fused to the Alp1 prepropeptide; **, active Alp1). Lanes: M, molecular weight marker proteins; 1, soluble protein fraction of E. coli BL21(DE3) cells without ΔN20Alp1-encoding vector; 2, soluble protein fraction of ΔN20Alp1-overproducing E. coli BL21(DE3) cells without PMSF; 3, after addition of 2 mM PMSF. (B) Schematic depiction of Alp1 in accordance with SignalP and Pfam. The domains represent the signal peptide (white), the peptidase inhibitor domain (gray), and the peptidase domain (black). (C) Western blot analysis showing the degradation of C3b, C4b, and C5 by increasing concentrations of E. coli BL21(DE3) crude extract containing active processed protease Alp1. As negative controls, Alp1 activity was inactivated by heat (HI) or by the addition of PMSF. Incubation of complement proteins with E. coli BL21(DE3) protein extract (w/o Alp1) did not lead to complement degradation.

We observed that the soluble protein extract of MBP-ΔN20Alp1-producing E. coli BL21(DE3) cells was efficiently degraded by the processed Alp1 protein (Fig. 4A). Since the autocatalytic processing of Alp1 resulted in the cleavage of the MBP fusion tag, no purification procedure based on affinity chromatography could be used for Alp1. Therefore, Alp1-containing crude extract of E. coli BL21(DE3) cells was used for coincubation with C3b, C4b, and C5. As shown in Fig. 4C, increasing concentrations led to complete degradation of all three human complement proteins, i.e., C3b, C4b, and C5. As a negative control, protein extract derived from an E. coli BL21(DE3) strain not producing ΔN20Alp1 was used, which did not lead to any degradation of the complement factors. Similarly, no cleavage occurred when the protease inhibitor PMSF was added to the ΔN20Alp1-containing protein extract or when the protein extract was heat inactivated. These findings confirm that Alp1 degrades the human complement factors C3b, C4b, and C5.

Growth and C3b degradation by the Δalp1 strain on different carbon and nitrogen sources.

The majority of proteases that were secreted when A. fumigatus was grown in AMM were serine proteases like Alp1, whereas on other carbon and nitrogen sources also other proteases were secreted (10). To test whether these proteases also cleave C3b, the wild-type, Δalp1, and Δalp1C strains were grown in four different media. Medium 1 was AMM. Medium 2 contained AMM without a nitrogen and carbon source (AMM−N) and supplemented with 10 mM glucose to support initial growth and 1% (wt/vol) BSA. Medium 3 was AMM−N with 1% (wt/vol) BSA as the sole nitrogen and carbon source. Medium 4 consisted of AMM−N supplemented with 10 mM glucose and 0.4% (wt/vol) elastin.

The dry weight after growth in these media was measured. In AMM, dry weight was the same for all three strains. In medium 3, with BSA and glucose, and in medium 4, with BSA alone, the biomass of the Δalp1 strain was reduced by one-third compared to those of the wild-type strain and the reconstituted strain. In medium 4, with elastin, the Δalp1 strain did not grow well, most probably because of the absence of the major elastase Alp1, and reached only half of the biomass of the wild-type and Δalp1C strains (Fig. 5A).

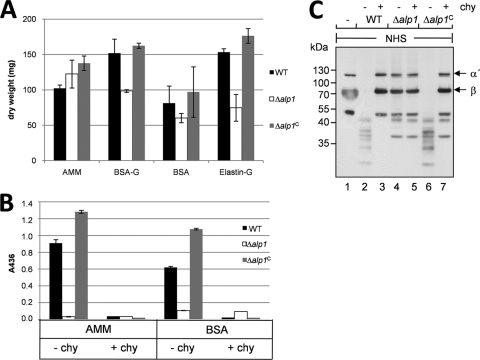

FIG. 5.

Growth and C3b degradation of the Δalp1 strain on different carbon and nitrogen sources. (A) Dry weight measurement after growth in different media. The wild-type (WT), Δalp1, and Δalp1C strains were grown in AMM, AMM−N supplemented with 10 mM glucose and 1% (wt/vol) BSA (BSA-G), AMM−N with 1% (wt/vol) BSA (BSA), or AMM−N with 10 mM glucose and 0.4% (wt/vol) elastin (Elastin-G). Dry weight was measured after 72 h of incubation. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) Protease activity after growth in BSA medium compared to AMM. Protease activity in the culture supernatants after 72 h of incubation was measured with an azocasein assay. Alp1 protease activity was inhibited by addition of chymostatin to the culture supernatants (+chy). (C) Degradation of C3b after growth in BSA medium. The wild-type, Δalp1, and Δalp1C strains were grown in AMM−N with 1% (wt/vol) BSA as the sole carbon and nitrogen source for 67 h. Culture supernatants were incubated with NHS, and C3b cleavage was analyzed by Western blotting.

Protease activity in BSA medium was measured for all strains. Protease-free BSA should promote secretion of metalloproteases (10). However, for the wild-type strain and the reconstituted strain, protease activity in the culture supernatant after growth with BSA was slightly lower than that after growth in AMM (Fig. 5B). This activity was almost completely inhibited by the addition of the inhibitor chymostatin to the culture supernatants of both the wild-type and reconstituted strains. For the Δalp1 strain, secretion of proteases other than Alp1 was expected to promote growth of the fungus in medium containing BSA as the sole nitrogen and carbon source. However, the proteolytic activity of culture supernatant of the Δalp1 strain was six times lower than that of wild-type supernatant (Fig. 5B). The proteases present in the culture supernatant were not inhibited by addition of chymostatin. Apparently, this low protease activity was sufficient to promote growth of the strain up to a level of 65% of the biomass of the wild type. Degradation of BSA, which supported growth, was indirectly seen (Fig. 5C, lanes 1, 3, 4, 5, and 7). The β chain of C3b and the BSA in the medium have the same molecular mass. In a Western blot directed against C3b, the β chain of C3b is therefore visible as a smear (Fig. 5C, lane 1). When BSA in the medium is degraded by proteases, the β chain of C3b is visible by Western blot analysis as a sharp band (Fig. 5C, lanes 4 and 5). The proteases secreted by the Δalp1 strain degraded BSA but did not cleave complement component C3b (Fig. 5C). Therefore, also under these conditions, Alp1 is the major protease of A. fumigatus that cleaves C3b.

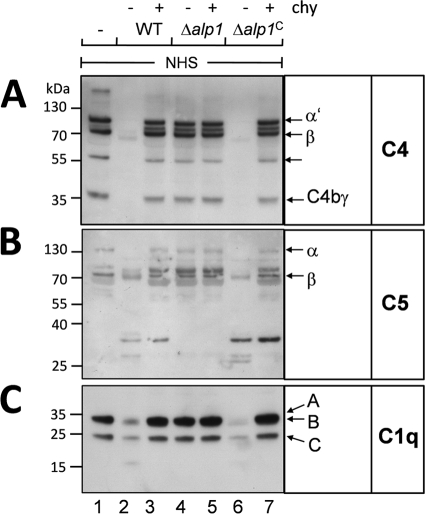

Degradation of complement proteins after growth in AMM.

C3b is an important opsonin, but other complement proteins also have essential functions in the defense against microbes. C5b, a cleavage product of C5, initiates formation of the membrane attack complex at a later stage of complement activation, and C5a represents a potent anaphylatoxin. C1q initiates the classical pathway of complement activation, and C4 is part of the C3 convertase of the classical pathway (12, 63, 64). When culture supernatant of the wild-type or Δalp1C strain was incubated with human serum that contains C4, C5, and C1q, subsequent Western blot analysis showed that C4 (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 and 6) was completely degraded. Degradation of C5 and C1q was also observed but was less prominent (Fig. 6B and C, lanes 2 and 6). Supernatant of the Δalp1 strain did not cleave C4, C5, or C1q (Fig. 6A to C, lanes 4 and 5). In the case of C4, a faint band of 80 kDa was visible after incubation with Δalp1 culture supernatant, but C4 remained mainly intact. These data confirmed the in vitro data obtained with the Alp1 protein produced by E. coli (Fig. 4), showing that degradation of complement proteins by Alp1 is not limited to C3b but also occurs with complement proteins C4, C5, and C1q.

FIG. 6.

Degradation of other complement proteins after growth in AMM. The wild-type, Δalp1, and Δalp1C strains were grown in AMM for 72 h without shaking. Culture supernatant of each strain was either pretreated with chymostatin (chy) or incubated directly with NHS for 60 min. Detection of cleavage fragments was performed by Western blotting with polyclonal antibodies directed against C4 (A), C5 (B), or C1q (C).

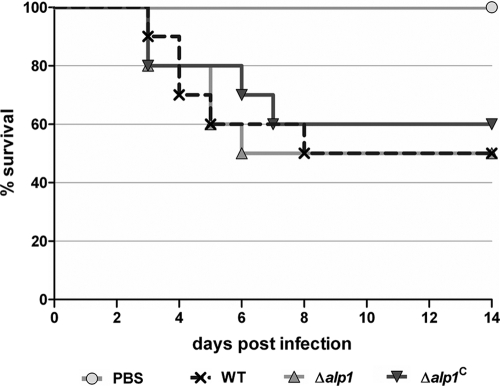

Virulence of the Δalp1 and Δalp1C strains in a cortisone acetate mouse infection model.

A cortisone acetate mouse model was applied to test the virulence of the Δalp1 mutant and to analyze the strain for a possible higher recruitment of neutrophils to the site of infection. Absence of Alp1 should lead to increased activation of complement on the hyphal surface and to elevated levels of anaphylatoxins. Due to the low numbers of neutrophils in a neutropenic mouse model, the impact of the homing of neutrophils on virulence could not be determined in previous studies (37, 58). However, in this cortisone acetate mouse model, the Δalp1 strain also showed no attenuation in virulence (Fig. 7), and no increased infiltration of neutrophils to the site of infection was visible (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Animal experiments. Virulence of the Δalp1 strain as well as the corresponding wild-type and reconstituted strains was tested in a cortisone acetate mouse infection model. Mice (n = 10) were immunosuppressed with cortisone acetate on days −3 and 0 and were infected intranasally with 1 × 105 spores of each strain in a 20-μl total volume. Immunosuppressed mice inoculated with PBS served as controls. Survival was monitored for 14 days.

DISCUSSION

In this study we report a novel mechanism of immune evasion for Aspergillus fumigatus. A. fumigatus secreted Alp1, a protease that efficiently cleaved components of the complement system, i.e., C3, C4, C5, and C1q, as well as IgG, and thus modulates complement activation on the hyphal surface.

The role of the complement system in the defense against A. fumigatus has not been extensively studied, but existing data indicate an important effect of this central host innate immune system. Upon incubation with serum, conidia were opsonized with C3b, which enhanced phagocytosis (61). A white mutant (pksP) of A. fumigatus (20), which was highly attenuated in virulence in a murine infection model (30), bound more C3b molecules per unit of conidial surface area and was subsequently better phagocytosed by macrophages (46, 61). In addition, the pathogenic aspergilli A. fumigatus and A. flavus bound fewer C3 molecules per unit of conidial surface area than did the less pathogenic species A. glaucus, A. nidulans, A. niger, A. ochraceus, A. terreus, A. versicolor, and A. wentii (15). This difference further supports the importance of complement modulation and inhibition for the virulence of pathogenic fungi. The major site of infection for A. fumigatus is the lungs, which represent an environment different from serum. However, all components of both the alternative and the classical pathways are present in human bronchoalveolar liquid (5, 40). Thus, the lungs are a site for complement activation, and inactivation also can occur in vivo since complement regulators are present. Downregulation of the complement cascade by binding of the human host complement regulators factor H, FHL-1, CFHR1, and/or C4BP has been shown for bacterial and fungal pathogens, e.g., A. fumigatus (2, 62), Candida albicans (33, 34), Streptococcus pneumoniae (13), Streptococcus pyogenes (25), Borrelia burgdorferi (1, 14, 27), Borrelia spielmanii (56), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (39, 44, 45), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (28). However, endogenous activities downregulating complement activation have been described for only a few pathogens (for a review, see reference 4). For P. aeruginosa, C3 degradation by the major secreted metalloproteinase elastase was reported (28, 53), and for C. albicans, C3 degradation (22) by a secreted protease was shown. This protease also cleaved the human proteinase inhibitors α2-macroglobulin and α1-proteinase inhibitor and degraded the Fc portion of IgG. Recently, aspartic proteases of C. albicans were shown to cleave C3b, C4b, and C5 (11). Cleavage of C3 and C5 was described for Porphyromonas gingivalis (67; for a review, see reference 57), a bacterium implicated in periodontal disease. Proteases of P. gingivalis also cleaved the C5a receptor on neutrophils (19). The Treponema denticola surface protease dentilisin hydrolyzed the α chain of C3b, thereby producing iC3b (68). The streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B (SpeB) degrades C3 (29, 60). Preincubation of serum with SpeB enhanced resistance of group A streptococci to complement-mediated lysis. A strain lacking SpeB was opsonized with more C3 fragments (29). Infection with the SpeB mutant resulted in migration of neutrophils to the site of infection, which phagocytosed SpeB mutant bacteria, whereas only few neutrophils were recruited in case of infection with the wild type (60). The cysteine protease EhCP1 of the protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica cleaved C3, immunoglobulin G, and pro-interleukin-18 (32). Salmonella enterica produces the surface protease PgtE, which cleaves C3b, C4b, and C5 (47). Recently, interpain A, a cysteine proteinase, was described as an important virulence factor of Prevotella intermedia (43). The protease cleaved C3 and thereby inhibited complement activation via all three pathways and increased serum resistance of P. intermedia.

The A. fumigatus protease Alp1 that we describe here showed a broad proteolytic activity. The degrading activity includes several human complement proteins, such as C3, C4b, C5, C1q, and IgG, as shown using supernatants and also protein extract of an Alp1-overproducing E. coli strain. Thus, proteolytic cleavage was not limited to complement component C3, as described for most proteases (with the exception of PgtE of S. enterica). Cleavage of these proteins was nearly complete so that after incubation hardly any degradation products were visible. The complement regulators factor H and C4BP were also degraded by culture supernatant. Since A. fumigatus hyphae did not bind and employ these molecules for complement inactivation on the hyphal surface, the cleavage of these regulators does not result in a counterproductive effect. The alp1 deletion strain lacked most of the complement-degrading activity. In Δalp1 cultures during growth on human serum, C3 remained intact longer than in wild-type cultures. Other proteases of A. fumigatus seem to act in concert with Alp1 in the degradation of complement proteins. However, Alp1 is the major protease involved in this degradation process.

The A. fumigatus genome contains sequences coding for 56 known or putative proteases (8). Since A. fumigatus is a saprophyte, proteases were thought to be essential for survival in the natural habitat and to be a possible virulence determinant that might enable the fungus to grow in the lungs, a habitat rich in elastin. The secreted (36, 49, 51) and cell wall-attached (50) protease deletion strains of A. fumigatus generated until now grew as invasively as the wild type. Alp1 is a major secreted protease of A. fumigatus and is also secreted during infection of the lungs (49, 58). It exhibits elastase activity and cleaves elastin. However, an alp1-disrupted A. fumigatus strain was as virulent in a cyclophosphamide-based murine infection model as the wild type and showed the same invasive growth (37, 58). Recently, a global protease regulator was identified in A. fumigatus. It governs expression of multiple secreted proteases (Alp1, MEP, Dpp4, CpdS, AFUA_2G17330, and AFUA_7G06220). Culture filtrate from a deletion strain exhibited reduced killing of lung epithelial cells and lysis of erythrocytes. However, as in protease single-deletion strains, the downregulation of multiple proteases had no effect on virulence of the fungus in mouse infection models with either cortisone acetate alone or cyclophosphamide and cortisone acetate (3, 54).

Culture filtrate of A. fumigatus suppresses chemotaxis and O2− release by neutrophils. With an alp1-disrupted strain, this suppression was less prominent and the cells showed more motility and O2− release (18). Here we applied a cortisone acetate mouse model to test the impact of these effects on the virulence of the Δalp1 and Δalp1C strains. In these mice, neutrophils are not depleted as they are in cyclophosphamide-treated mice. Degradation of complement by A. fumigatus should lead to less production of anaphylatoxins and consequently in impaired homing of neutrophils. Such an effect was seen for S. pyogenes protease SpeB (60). However, no increase in neutrophil infiltration was detected for the Δalp1 strain. Despite these data based on animal experiments, the influence of Alp1 might be more subtle than could be measured in these experiments. Secretion of proteases might play a role in a more secluded area such as the central nervous system (CNS). Vogl et al. (62) showed that complement proteins have low abundance in A. fumigatus brain abscesses and that hyphae isolated from liquor showed decreased C3 deposition. This finding could be due to the proposed A. fumigatus complement inhibitor (65). A more recent study by Rambach et al. (45a) suggests that a secreted protease, most likely Alp1, causes complement degradation in cerebral aspergillosis. Our findings corroborate the central role of Alp1 in this cleavage.

In conclusion, we describe a new function for a major protease of A. fumigatus. Alp1 efficiently cleaves important human components of the complement cascade, which leads to downregulation of complement activation at the hyphal surface. Thus, A. fumigatus possesses at least two distinct mechanisms to evade the human complement system: the binding of complement regulators to conidia and the secretion of the protease Alp1 by hyphae.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the “Grundlagenfonds” of the Hans Knöll Institute to A.A.B. and P.F.Z. and by Priority Program 1160 (colonization and infection by human-pathogenic fungi) of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to A.A.B. and P.F.Z.

Editor: G. S. Deepe, Jr.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 May 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alitalo, A., T. Meri, L. Ramo, T. S. Jokiranta, T. Heikkila, I. J. Seppala, J. Oksi, M. Viljanen, and S. Meri. 2001. Complement evasion by Borrelia burgdorferi: serum-resistant strains promote C3b inactivation. Infect. Immun. 69:3685-3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behnsen, J., A. Hartmann, J. Schmaler, A. Gehrke, A. A. Brakhage, and P. F. Zipfel. 2008. The opportunistic human pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus evades the host complement system. Infect. Immun. 76:820-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergmann, A., T. Hartmann, T. Cairns, E. M. Bignell, and S. Krappmann. 2009. A regulator of Aspergillus fumigatus extracellular proteolytic activity is dispensable for virulence. Infect. Immun. 77:4041-4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blom, A. M., T. Hallstrom, and K. Riesbeck. 2009. Complement evasion strategies of pathogens—acquisition of inhibitors and beyond. Mol. Immunol. 46:2808-2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolger, M. S., D. S. Ross, H. Jiang, M. M. Frank, A. J. Ghio, D. A. Schwartz, and J. R. Wright. 2007. Complement levels and activity in the normal and LPS-injured lung. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 292:L748-L759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brakhage, A. A. 2005. Systemic fungal infections caused by Aspergillus species: epidemiology, infection process and virulence determinants. Curr. Drug Targets 6:875-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brock, M. 2008. Physiology and metabolic requirements of pathogenic fungi, p. 63-82. In A. A. Brakhage and P. F. Zipfel (ed.), The mycota. VI. Human and animal relationships. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany.

- 9.da Silva Ferreira, M. E., M. R. Kress, M. Savoldi, M. H. Goldman, A. Hartl, T. Heinekamp, A. A. Brakhage, and G. H. Goldman. 2006. The akuB(KU80) mutant deficient for nonhomologous end joining is a powerful tool for analyzing pathogenicity in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot. Cell 5:207-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gifford, A. H., J. R. Klippenstein, and M. M. Moore. 2002. Serum stimulates growth of and proteinase secretion by Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect. Immun. 70:19-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gropp, K., L. Schild, S. Schindler, B. Hube, P. F. Zipfel, and C. Skerka. 2009. The yeast Candida albicans evades human complement attack by secretion of aspartic proteases. Mol. Immunol. 47:465-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gros, P., F. J. Milder, and B. J. Janssen. 2008. Complement driven by conformational changes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:48-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammerschmidt, S., V. Agarwal, A. Kunert, S. Haelbich, C. Skerka, and P. F. Zipfel. 2007. The host immune regulator factor H interacts via two contact sites with the PspC protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae and mediates adhesion to host epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 178:5848-5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hellwage, J., T. Meri, T. Heikkila, A. Alitalo, J. Panelius, P. Lahdenne, I. J. Seppala, and S. Meri. 2001. The complement regulator factor H binds to the surface protein OspE of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8427-8435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henwick, S., S. V. Hetherington, and C. C. Patrick. 1993. Complement binding to Aspergillus conidia correlates with pathogenicity. J. Lab Clin. Med. 122:27-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hortschansky, P., M. Eisendle, Q. Al-Abdallah, A. D. Schmidt, S. Bergmann, M. Thön, O. Kniemeyer, B. Abt, B. Seeber, E. R. Werner, M. Kato, A. A. Brakhage, and H. Haas. 2007. Interaction of HapX with the CCAAT-binding complex—a novel mechanism of gene regulation by iron. EMBO J. 26:3157-3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibrahim-Granet, O., B. Philippe, H. Boleti, E. Boisvieux-Ulrich, D. Grenet, M. Stern, and J. P. Latgé. 2003. Phagocytosis and intracellular fate of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia in alveolar macrophages. Infect. Immun. 71:891-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikegami, Y., R. Amitani, T. Murayama, R. Nawada, W. J. Lee, R. Kawanami, and F. Kuze. 1998. Effects of alkaline protease or restrictocin deficient mutants of Aspergillus fumigatus on human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Eur. Respir. J. 12:607-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jagels, M. A., J. Travis, J. Potempa, R. Pike, and T. E. Hugli. 1996. Proteolytic inactivation of the leukocyte C5a receptor by proteinases derived from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 64:1984-1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jahn, B., A. Koch, A. Schmidt, G. Wanner, H. Gehringer, S. Bhakdi, and A. A. Brakhage. 1997. Isolation and characterization of a pigmentless-conidium mutant of Aspergillus fumigatus with altered conidial surface and reduced virulence. Infect. Immun. 65:5110-5117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Józsi, M., and P. F. Zipfel. 2008. Factor H family proteins and human diseases. Trends Immunol. 29:380-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaminishi, H., H. Miyaguchi, T. Tamaki, N. Suenaga, M. Hisamatsu, I. Mihashi, H. Matsumoto, H. Maeda, and Y. Hagihara. 1995. Degradation of humoral host defense by Candida albicans proteinase. Infect. Immun. 63:984-988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kniemeyer, O., F. Lessing, O. Scheibner, C. Hertweck, and A. A. Brakhage. 2006. Optimisation of a 2-D gel electrophoresis protocol for the human-pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Curr. Genet. 49:178-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kojima, S., T. Minagawa, and K. Miura. 1997. The propeptide of subtilisin BPN′ as a temporary inhibitor and effect of an amino acid replacement on its inhibitory activity. FEBS Lett. 411:128-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotarsky, H., J. Hellwage, E. Johnsson, C. Skerka, H. G. Svensson, G. Lindahl, U. Sjobring, and P. F. Zipfel. 1998. Identification of a domain in human factor H and factor H-like protein-1 required for the interaction with streptococcal M proteins. J. Immunol. 160:3349-3354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozel, T. R., M. A. Wilson, T. P. Farrell, and S. M. Levitz. 1989. Activation of C3 and binding to Aspergillus fumigatus conidia and hyphae. Infect. Immun. 57:3412-3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kraiczy, P., C. Skerka, M. Kirschfink, V. Brade, and P. F. Zipfel. 2001. Immune evasion of Borrelia burgdorferi by acquisition of human complement regulators FHL-1/reconectin and Factor H. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:1674-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunert, A., J. Losse, C. Gruszin, M. Huhn, K. Kaendler, S. Mikkat, D. Volke, R. Hoffmann, T. S. Jokiranta, H. Seeberger, U. Moellmann, J. Hellwage, and P. F. Zipfel. 2007. Immune evasion of the human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa: elongation factor Tuf is a factor H and plasminogen binding protein. J. Immunol. 179:2979-2988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuo, C. F., Y. S. Lin, W. J. Chuang, J. J. Wu, and N. Tsao. 2008. Degradation of complement 3 by streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B inhibits complement activation and neutrophil opsonophagocytosis. Infect. Immun. 76:1163-1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langfelder, K., B. Jahn, H. Gehringer, A. Schmidt, G. Wanner, and A. A. Brakhage. 1998. Identification of a polyketide synthase gene (pksP) of Aspergillus fumigatus involved in conidial pigment biosynthesis and virulence. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 187:79-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li, Y., Z. Hu, F. Jordan, and M. Inouye. 1995. Functional analysis of the propeptide of subtilisin E as an intramolecular chaperone for protein folding. Refolding and inhibitory abilities of propeptide mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 270:25127-25132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melendez-Lopez, S. G., S. Herdman, K. Hirata, M. H. Choi, Y. Choe, C. Craik, C. R. Caffrey, E. Hansell, B. Chavez-Munguia, Y. T. Chen, W. R. Roush, J. McKerrow, L. Eckmann, J. Guo, S. L. Stanley, Jr., and S. L. Reed. 2007. Use of recombinant Entamoeba histolytica cysteine proteinase 1 to identify a potent inhibitor of amebic invasion in a human colonic model. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1130-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meri, T., A. M. Blom, A. Hartmann, D. Lenk, S. Meri, and P. F. Zipfel. 2004. The hyphal and yeast forms of Candida albicans bind the complement regulator C4b-binding protein. Infect. Immun. 72:6633-6641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meri, T., A. Hartmann, D. Lenk, R. Eck, R. Würzner, J. Hellwage, S. Meri, and P. F. Zipfel. 2002. The yeast Candida albicans binds complement regulators factor H and FHL-1. Infect. Immun. 70:5185-5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Misasi, R., H. P. Huemer, W. Schwaeble, E. Solder, C. Larcher, and M. P. Dierich. 1989. Human complement factor H: an additional gene product of 43 kDa isolated from human plasma shows cofactor activity for the cleavage of the third component of complement. Eur. J. Immunol. 19:1765-1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monod, M., S. Paris, D. Sanglard, K. Jaton-Ogay, J. Bille, and J. P. Latgé. 1993. Isolation and characterization of a secreted metalloprotease of Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect. Immun. 61:4099-4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monod, M., S. Paris, J. Sarfati, K. Jaton-Ogay, P. Ave, and J. P. Latgé. 1993. Virulence of alkaline protease-deficient mutants of Aspergillus fumigatus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 106:39-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neuhoff, V., N. Arold, D. Taube, and W. Ehrhardt. 1988. Improved staining of proteins in polyacrylamide gels including isoelectric focusing gels with clear background at nanogram sensitivity using Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 and R-250. Electrophoresis 9:255-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ngampasutadol, J., S. Ram, S. Gulati, S. Agarwal, C. Li, A. Visintin, B. Monks, G. Madico, and P. A. Rice. 2008. Human factor H interacts selectively with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and results in species-specific complement evasion. J. Immunol. 180:3426-3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okroj, M., Y. F. Hsu, D. Ajona, R. Pio, and A. M. Blom. 2008. Non-small cell lung cancer cells produce a functional set of complement factor I and its soluble cofactors. Mol. Immunol. 45:169-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pangburn, M. K., V. P. Ferreira, and C. Cortes. 2008. Discrimination between host and pathogens by the complement system. Vaccine 26(Suppl 8):I15-I21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pfaller, M. A., and D. J. Diekema. 2004. Rare and emerging opportunistic fungal pathogens: concern for resistance beyond Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4419-4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Potempa, M., J. Potempa, T. Kantyka, K. A. Nguyen, K. Wawrzonek, S. P. Manandhar, K. Popadiak, K. Riesbeck, S. Eick, and A. M. Blom. 2009. Interpain A, a cysteine proteinase from Prevotella intermedia, inhibits complement by degrading complement factor C3. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ram, S., D. P. McQuillen, S. Gulati, C. Elkins, M. K. Pangburn, and P. A. Rice. 1998. Binding of complement factor H to loop 5 of porin protein 1A: a molecular mechanism of serum resistance of nonsialylated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Exp. Med. 188:671-680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ram, S., A. K. Sharma, S. D. Simpson, S. Gulati, D. P. McQuillen, M. K. Pangburn, and P. A. Rice. 1998. A novel sialic acid binding site on factor H mediates serum resistance of sialylated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Exp. Med. 187:743-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45a.Rambach, G., D. Dum, I. Mohsenipour, M. Hagleitner, R. Wurzner, C. Lass-Florl, and C. Speth.2010. Secretion of a fungal protease represents a complement evasion mechanism in cerebral aspergillosis. Mol.Immunol. 47:38-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rambach, G., M. Hagleitner, I. Mohsenipour, C. Lass-Florl, H. Maier, R. Würzner, M. P. Dierich, and C. Speth. 2005. Antifungal activity of the local complement system in cerebral aspergillosis. Microbes Infect. 7:1285-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramu, P., R. Tanskanen, M. Holmberg, K. Lahteenmaki, T. K. Korhonen, and S. Meri. 2007. The surface protease PgtE of Salmonella enterica affects complement activity by proteolytically cleaving C3b, C4b and C5. FEBS Lett. 581:1716-1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rawlings, N. D., and A. J. Barrett. 1994. Families of serine peptidases. Methods Enzymol. 244:19-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reichard, U., S. Buttner, H. Eiffert, F. Staib, and R. Ruchel. 1990. Purification and characterisation of an extracellular serine proteinase from Aspergillus fumigatus and its detection in tissue. J. Med. Microbiol. 33:243-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reichard, U., G. T. Cole, T. W. Hill, R. Ruchel, and M. Monod. 2000. Molecular characterization and influence on fungal development of ALP2, a novel serine proteinase from Aspergillus fumigatus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290:549-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reichard, U., G. T. Cole, R. Ruchel, and M. Monod. 2000. Molecular cloning and targeted deletion of PEP2 which encodes a novel aspartic proteinase from Aspergillus fumigatus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290:85-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 53.Schmidtchen, A., E. Holst, H. Tapper, and L. Bjorck. 2003. Elastase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa degrade plasma proteins and extracellular products of human skin and fibroblasts, and inhibit fibroblast growth. Microb. Pathog. 34:47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharon, H., S. Hagag, and N. Osherov. 2009. Transcription factor PrtTp controls expression of multiple secreted proteases in the human pathogenic mold Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect. Immun. 77:4051-4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shevchenko, A., M. Wilm, O. Vorm, and M. Mann. 1996. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68:850-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siegel, C., P. Herzberger, C. Skerka, V. Brade, V. Fingerle, U. Schulte-Spechtel, B. Wilske, P. F. Zipfel, R. Wallich, and P. Kraiczy. 2008. Binding of complement regulatory protein factor H enhances serum resistance of Borrelia spielmanii sp. nov. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 298:292-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Slaney, J. M., and M. A. Curtis. 2008. Mechanisms of evasion of complement by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Front. Biosci. 13:188-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith, J. M., C. M. Tang, S. Van Noorden, and D. W. Holden. 1994. Virulence of Aspergillus fumigatus double mutants lacking restriction and an alkaline protease in a low-dose model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Infect. Immun. 62:5247-5254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sturtevant, J. E., and J. P. Latgé. 1992. Interactions between conidia of Aspergillus fumigatus and human complement component C3. Infect. Immun. 60:1913-1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Terao, Y., Y. Mori, M. Yamaguchi, Y. Shimizu, K. Ooe, S. Hamada, and S. Kawabata. 2008. Group A streptococcal cysteine protease degrades c3 (c3b) and contributes to evasion of innate immunity. J. Biol. Chem. 283:6253-6260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsai, H. F., Y. C. Chang, R. G. Washburn, M. H. Wheeler, and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 1998. The developmentally regulated alb1 gene of Aspergillus fumigatus: its role in modulation of conidial morphology and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 180:3031-3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vogl, G., I. Lesiak, D. B. Jensen, S. Perkhofer, R. Eck, C. Speth, C. Lass-Florl, P. F. Zipfel, A. M. Blom, M. P. Dierich, and R. Würzner. 2008. Immune evasion by acquisition of complement inhibitors: the mould Aspergillus binds both factor H and C4b binding protein. Mol. Immunol. 45:1485-1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walport, M. J. 2001. Complement. First of two parts. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:1058-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walport, M. J. 2001. Complement. Second of two parts. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:1140-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Washburn, R. G., C. H. Hammer, and J. E. Bennett. 1986. Inhibition of complement by culture supernatants of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Infect. Dis. 154:944-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weidner, G., C. d'Enfert, A. Koch, P. C. Mol, and A. A. Brakhage. 1998. Development of a homologous transformation system for the human pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus based on the pyrG gene encoding orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase. Curr. Genet. 33:378-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wingrove, J. A., R. G. DiScipio, Z. Chen, J. Potempa, J. Travis, and T. E. Hugli. 1992. Activation of complement components C3 and C5 by a cysteine proteinase (gingipain-1) from Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis. J. Biol. Chem. 267:18902-18907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamazaki, T., M. Miyamoto, S. Yamada, K. Okuda, and K. Ishihara. 2006. Surface protease of Treponema denticola hydrolyzes C3 and influences function of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Microbes Infect. 8:1758-1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zipfel, P. F., and C. Skerka. 2009. Complement regulators and inhibitory proteins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9:729-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zipfel, P. F., R. Würzner, and C. Skerka. 2007. Complement evasion of pathogens: common strategies are shared by diverse organisms. Mol. Immunol. 44:3850-3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]