Abstract

The mutant prevention concentration (MPC) for ciprofloxacin was determined for two Rhodococcus equi strains. The MPC for both strains was 32 μg/ml, which is above the peak serum concentration of ciprofloxacin obtainable by oral administration in humans. Nine single nucleotide changes corresponding to eight amino acid substitutions in the quinolone resistance-determining regions of DNA gyrase subunits A and B were characterized. Only mutants with amino acid changes in Ser-83 of GyrA were highly resistant (≥64 μg/ml). Our results suggest that ciprofloxacin monotherapy against R. equi infection may result in the emergence of ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants.

Rhodococcus equi, a facultative intracellular Gram-positive coccobacillus phylogenetically related to the genus Mycobacterium, is a known cause of suppurative pneumonia and ulcerative enteritis in 1- to 3-month-old foals (24). R. equi is also known as an important pathogen of immunosuppressed human patients (27). Recently, fluoroquinolones have been used in humans and have also been used on an experimental basis to treat horses for R. equi infection (8, 17, 25). Although the majority of clinical isolates of R. equi from previous surveillance studies were reported to be susceptible to fluoroquinolones (1, 16, 21), treatment failures and fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates have been reported (12, 19, 22).

The development of bacterial resistance has been hypothesized to be due in part to the use of antibiotics at therapeutic doses that usually block only the growth of susceptible wild-type cells (5, 6). However, under these conditions, the concentration may be too low to eliminate the small numbers of spontaneous drug-resistant mutants in the population of infecting bacteria. Drug-resistant mutants in the infecting population were hypothesized to be enriched during growth within a drug concentration range known as the mutant selection window (MSW) (5, 6). The lower boundary of the MSW is the MIC99 of the drug. The upper boundary consists of the mutant prevention concentration (MPC), defined as the drug concentration that inhibits the growth of the subpopulation of cells that are the least susceptible due to spontaneous single-step mutants in the population. Experimentally, MPC is the lowest drug concentration that prevents mutant bacterial colony formation from ≥1010 CFU (4). This suggests that maintaining antibiotic concentrations above the MPC throughout therapy may reduce the chance for enrichment of single-step resistance mutants and selection of high-level resistance. A higher level of resistance would be a rare event since it would require the acquisition of two or more spontaneous mutations by bacterial cells.

Niwa et al. (20) previously reported on the association between fluoroquinolone resistance and a single amino acid substitution in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of DNA gyrase subunit A gene (gyrA) of R. equi. However, susceptibility was determined only at a single drug concentration, and the diversity of the mutant population was not examined over a variable range of ciprofloxacin concentrations using a large number of cells. Therefore, in order to determine the risk of selecting for ciprofloxacin resistance and to correlate mutations with a resistance phenotype in R. equi, we determined the MPC and characterized the diversity of ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants by DNA sequence analysis of the QRDR in the target genes encoding DNA gyrase subunit A (gyrA) and subunit B (gyrB).

R. equi strain W5234 was isolated from an HIV-positive patient, and R. equi strain ATCC 6939T was isolated from a lung abscess of a foal (14). R. equi cells were grown in brain heart infusion broth (Becton Dickinson and Co., LePont de Claix, France) for 48 h at 35°C with vigorous shaking, harvested by centrifugation, and then resuspended in 20 ml of fresh brain heart infusion broth. The numbers of CFU/ml were determined by plating serial 10-fold dilutions on drug-free Columbia blood agar base plates (Becton Dickenson and Co.). At least 1 × 1010 cells were applied onto five Columbia blood agar base plates containing various concentrations of ciprofloxacin (USP, Rockville, MD). The agar plates were examined for the emergence of ciprofloxacin-resistant colonies after incubation at 35°C for 4 days. The MIC99 was determined after individual ciprofloxacin-resistant colonies were counted. The fraction of resistant colonies recovered from the agar plates was plotted against the drug concentration, and the MPC was determined. The MICs of ciprofloxacin for parent strains and mutants were determined by the broth microdilution method using cation-supplemented Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco, Detroit, MI) according to the guidelines of the current NCCLS/CLSI M24-A standard (2). At least two ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants were selected at each concentration. Mutants were confirmed by a combination of two passages on an agar plate whose drug concentration was the same as that upon which the mutant was selected and one passage on a drug-free agar plate. Each experiment was carried out twice.

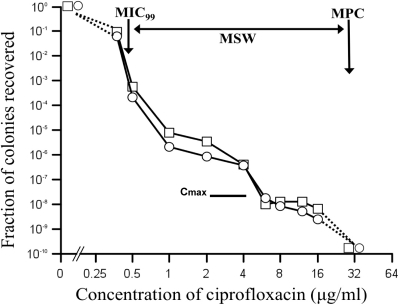

Figure 1 shows the MSW of ciprofloxacin for two R. equi strains (double arrow). The number of colonies recovered dropped gradually until reaching a plateau at approximately 1 to 4 μg/ml and then dropped a second time at higher drug concentrations. The MIC, MIC99, and MPC (Fig. 1, vertical arrows) of both W5234 and ATCC 6939T were 0.5, 0.42, and 32 μg/ml, respectively. In comparison, the Cmax for ciprofloxacin, the maximum concentration that can be achieved in serum, is 2.5 to 4.4 μg/ml (4, 13). The AUC24, the area under the concentration-time curve from 0 h to 24 h, is 24 μg·h/ml (26). The AUC24/MPC and AUC24/MIC ratios for both strains of R. equi were 0.75 h and 48 h, respectively. In comparison, an increase in resistance was observed when the AUC24/MIC ratio ranged between 20 and 150 h in a rabbit model of infection by Staphylococcus aureus (3), and the greatest increase in fluoroquinolone resistance was observed at an AUC24/MIC ratio of 24 to 62 h (7). With fluoroquinolones, an AUC24/MPC ratio ranging between 20 and 70 restricts the emergence of resistance mutants (6). The low AUC24/MPC ratio of 0.75 obtained for both isolates of R. equi again indicates the potential to enrich the mutant population. Together, our results suggest that monotherapy using ciprofloxacin against R. equi infection may be of high risk for the emergence of ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants since the obtainable therapeutic doses clearly remain within the MSW. Similarly, resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during levofloxacin monotherapy has been reported (9, 23). These results indicate that careful use of fluoroquinolones for the treatment of infection with R. equi and monitoring of MICs during the administration of ciprofloxacin should be considered.

FIG. 1.

Effect of ciprofloxacin concentration on recovery of single-step ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants. R. equi ATCC strain W6939T (open squares) and R. equi strain W5234 (open circles) were applied to Columbia blood agar base agar plates supplemented with ciprofloxacin and then incubated for 4 days. Cell survival is shown as the fraction of ciprofloxacin-resistant colonies relative to the number of CFU applied to ciprofloxacin-free plates. The small downward arrow indicates the MIC99, whereas the larger downward arrow indicates the mutant prevention concentration (MPC) for ciprofloxacin. The horizontal double arrow shows the mutant selection window. Cmax is denoted by the thick horizontal line.

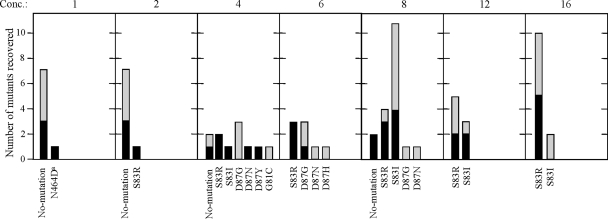

To determine the correlation between ciprofloxacin susceptibility and genetic variation, the parent strains and ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants were characterized by sequence analysis of the QRDR of gyrA and gyrB as described previously (20). Totals of 36 and 38 ciprofloxacin-resistant colonies were obtained from R. equi strains W5234 and ATCC 6939T, respectively, at the ciprofloxacin concentrations shown in Fig. 2. The correlation between each amino acid substitution and the ciprofloxacin concentration is presented in Table 1. Nine nucleotide mutants corresponding to seven different amino acid substitutions denoted as mutant types I to VII in gyrA were observed in 56 of 74 mutants. Importantly, high-level resistance (MIC of ≥64 μg/ml), was observed only for mutants harboring amino acid substitutions at Ser-83. These mutants were isolated from plates containing a relatively high level of ciprofloxacin (≥12 μg/ml) but not at a lower drug concentration. The high level of ciprofloxacin resistance in mutants with amino acid substitutions at Ser-83 suggests that this amino acid may play an important function in reducing the affinity of the active site of DNA gyrase to quinolones (11). Mutants with an intermediate level of resistance (8 μg/ml to 32 μg/ml) were also identified (Table 1). These mutants were obtained from plates with lower ciprofloxacin concentrations of 8 to 16 μg/ml. A single amino acid substitution, Asn-464 to Asp, was detected in the QRDR of gyrB. The Asn-464 to Asp mutation in the QRDR of gyrB has been previously observed in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (18). In 18 of 74 resistant colonies, nucleotide changes were not observed in the QRDR of either the gyrA or gyrB gene of W5234 and ATCC 6939T (Table 1). Two of 18 non-gyrase mutants had an intermediate MIC of 16 to 32 μg/ml, whereas 16 of 18 mutants showed low levels of resistance. Resistance in non-gyrase mutants may be due to an alteration of membrane permeability or the activation of efflux pumps, whereas high levels of resistance were only associated with substitutions in the target enzyme (21, 29). Alternatively, resistance to ciprofloxacin in the non-gyrase mutants may be due to mutations in the genes for topoisomerase IV (parC and parE) that were previously identified as a target for fluoroquinolones (6, 11, 18, 26); however, parC and parE have not been identified in other mycolic acid-containing bacteria phylogenetically related to R. equi (10, 28). Overall, resistant mutants detected in the wild-type population were diverse and may be a clinically relevant reservoir following enrichment within the MSW.

FIG. 2.

Effect of ciprofloxacin concentration on the diversity of ciprofloxacin-resistant R. equi mutations. Each section shows the resistance mutation alleles recovered from agar plates supplemented with the indicated concentration of ciprofloxacin (μg/ml). Vertical bars indicate the number of mutants analyzed; black bars represent mutants derived from R. equi W5234, and gray bars represent mutants derived from R. equi ATCC 6939T. All amino acid substitutions were in GyrA except N464Da, derived from an amino acid substitution in GyrB.

TABLE 1.

Correlation among amino acid substitutions in GyrA and GyrB, concentrations of ciprofloxacin on which mutants were selected, and MICs

| Mutation type | Amino acid substitutiona in: |

Concn of drug | Resultb using strain: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W5234 (MIC, 0.5μg/ml) |

ATCC 6939T (MIC, 0.5μg/ml) |

||||||

| GyrA | GyrB | No. of mutants isolated | MIC (μg/ml) or range | No. of mutants isolated | MIC (μg/ml) or range | ||

| I | Ser-83 to Arg | ND | 16 | 5 | 64 | 5 | 32-64 |

| 12 | 2 | 64 | 3 | 128 | |||

| 8 | 3 | 32-64 | 1 | 64 | |||

| 6 | 3 | 32-64 | 0 | NA | |||

| 4 | 2 | 32 | 0 | NA | |||

| 2 | 1 | 8 | 0 | NA | |||

| II | Ser-83 to Ile | ND | 16 | 0 | NA | 2 | 64 |

| 12 | 2 | 64 | 1 | 128 | |||

| 8 | 4 | 32-64 | 7 | 32-128 | |||

| 4 | 1 | 32 | 0 | NA | |||

| III | Asp-87 to Gly | ND | 8 | 0 | NA | 1 | 16 |

| 6 | 1 | 16 | 2 | 16 | |||

| 4 | 0 | NA | 3 | 8 | |||

| IV | Asp-87 to Asn | ND | 8 | 0 | NA | 1 | 32 |

| 6 | 0 | NA | 1 | 16 | |||

| 4 | 1 | 16 | 0 | NA | |||

| V | Asp-87 to His | ND | 6 | 0 | 16 | 1 | 16 |

| VI | Asp-87 to Tyr | ND | 4 | 1 | 8 | 0 | NA |

| VII | Gly-81 to Cys | ND | 4 | 0 | NA | 1 | 8 |

| VIII | ND | Asn-464 to Asp | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | NA |

| IX | ND | ND | 8 | 2 | 16-32 | 0 | NA |

| 4 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 4 | |||

| 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2-4 | |||

| 1 | 3 | 2-4 | 4 | 1-4 | |||

The first amino acid represents the wild-type amino acid, and the second amino acid represents the mutant amino acid occurring at that position. Numbering of the amino acid residues in GyrA and GyrB for the mutants analyzed in this study was according to those of E. coliGyrA (GenBank accession no. CAA68611) and GyrB (GenBank accession no. BAA20341). ND, not detected.

NA, not applicable.

In this study, we investigated the potential risk for the emergence of ciprofloxacin resistance in R. equi by determining its MSW. Molecular characterization of the mutations associated with ciprofloxacin phenotypes may provide an important adjunct diagnostic tool for patient management to reduce the emergence of resistance. Although fluoroquinolones are still effective and requisite agents against most clinical strains of R. equi infection of humans and horses, further study will be needed for better dosing regimens of ciprofloxacin, or a combination of agents, to treat R. equi infection while preventing the emergence of resistant mutants.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank sequence accession numbers for the partial nucleotide sequences of the gyrA and gyrB ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants isolated in this study are GQ468775 to GQ468790 and GQ369761 to GQ369763, respectively.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 May 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bowersock, T. L., S. A. Salmon, E. S. Portis, J. F. Prescott, D. A. Robison, C. W. Ford, and J. L. Watts. 2000. MICs of oxazolidinone for Rhodococcus equi strains isolated from humans and animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1367-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CLSI/NCCLS. 2003. Susceptibility testing for mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes. Approved standard M24-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 3.Cui, J., Y. Liu, R. Wang, W. Tong, K. Drlica, and X. Xhao. 2006. The mutant selection window in rabbits infected with Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 194:1601-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong, Y., X. Zhao, B. N. Kreiswirth, and K. Drlica. 2000. Mutant protection concentration as a measure of antibiotic potency: studies with clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2581-2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drlica, K. 2003. The mutant selection window and antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:11-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drlica, K., and X. Zhao. 2007. Mutant selection window hypothesis updated. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:681-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Firsov, A. A., S. N. Vostrov, I. Y. Lubenko, K. Drlica, Y. A. Portnoy, and S. H. Zinner. 2003. In vitro pharmacodynamic evaluation of the mutant selection window hypothesis using four fluoroquinolones against Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1604-1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giguere, S., and J. F. Prescott. 1997. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Rhodococcus equi infections in foals. Vet. Microbiol. 56:313-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ginsburg, A. S., S. C. Woowine, N. Hooper, W. H. Benjamin, Jr., W. R. Bishai, S. E. Dorman, and T. R. Sterling. 2003. The rapid development of fluoroquinolone resistance in M. tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 349:1977-1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillemin, I., V. Jarlier, and E. Cambau. 1998. Correlation between quinolone susceptibility patterns and sequences in the A and B subunits of DNA gyrase in Mycobacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2084-2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopkins, K. L., R. H. Davies, and E. J. Threlfall. 2005. Mechanisms of quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli and Salmonella: recent developments. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 25:358-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsueh, P. R., C. C. Hung, L. J. Teng, M. C. Yu, Y. C. Chen, H. K. Wang, and K. T. Luh. 1998. Report of invasive Rhodococcus equi infections in Taiwan, with an emphasis on the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:370-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Israel, D., G. Gillum, M. Turik, K. Harvey, J. Ford, H. Dalton, M. Towle, R. Echols, A. H. Heller, and R. Polk. 1993. Pharmacokinetics and serum bactericidal titers of ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin following multiple oral doses in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:2193-2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magnusson, H. 1923. Spezifische infektiose Pneumonie beim Fohlen. Ein neuer Eiterreger beim Pferd. Arch. Wiss. Prakt. Tierhelkd. 50:22-28. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reference deleted.

- 16.McNeil, M. M., and J. M. Brown. 1992. Distribution and antimicrobial susceptibility of Rhodococcus equi from clinical specimens. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 8:437-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moretti, F., E. Quiros-Roldan, S. Casari, P. Viale, A. Chiodera, and G. Carosi. 2002. Rhodococcus equi: pulmonary cavitation lesion in patient infected with HIV cured by levofloxacin and rifampicin. AIDS 16:1440-1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mouneimne, H., J. Robert, V. Jarlier, and E. Cambau. 1999. Type II topoisomerase mutations in ciprofloxacin-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:62-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munoz, P., J. Palomo, J. Guinea, J. Yanez, M. Giannella, and E. Bouza. 2008. Relapsing Rhodococcus equi infection in a heart transplant recipient successfully treated with long-term linezolid. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 60:197-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niwa, H., S. Hobo, and T. Anzai. 2006. A nucleotide mutation associated with fluoroquinolone resistance observed in gyrA of in vitro obtained Rhodococcus equi mutants. Vet. Microbiol. 115:264-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niwa, H., S. Hobo, T. Anzai, and T. Higuchi. 2005. Antimicrobial susceptibility of 616 Rhodococcus equi strains isolated from tracheobronchial aspirates of foals suffering from respiratory disease in Japan. J. Equine Sci. 16:99-104. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordmann, P., E. Rouveix, M. Guenounou, and M. H. Nicolas. 1992. Pulmonary abscess due to a rifampin and fluoroquinolone resistant Rhodococcus equi strain in a HIV infected patient. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 11:557-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perlman, D. C., W. M. El Sadr, L. B. Heifets, E. T. Nelson, J. P. Matts, K. Chirgwin, N. Salomon, E. E. Telzak, O. Klein, B. N. Kreiswirth, J. M. Musser, and R. Hafner for the Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS 019 and the AIDS Clinical Trials Group 222 Protocol Team. 1997. Susceptibility to levofloxacin of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from patients with HIV-related tuberculosis and characterization of a strain with levofloxacin monoresistance. AIDS 11:1473-1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prescott, J. F. 1991. Rhodococcus equi: an animal and human pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:20-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scotton, P. G., E. Tonon, M. Giobbia, M. Gallucci, R. Rigoli, and A. Vaglia. 2000. Rhodococcus equi nosocomial meningitis cured by levofloxacin and shunt removal. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:223-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Bambeke, F., J. M. Michot, J. Van Eldere, and P. M. Tulkens. 2005. Quinolones in 2005: an update. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11:256-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstock, D. M., and A. E. Brown. 2002. Rhodococcus equi: an emerging pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:1379-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao, X., and K. Drlica. 2002. Restricting the selection of antibiotic-resistant mutant bacteria: measurement and potential use of the mutant selection window. J. Infect. Dis. 185:561-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou, J., Y. Dong, X. Zhao, S. Lee, A. Amin, S. Ramaswamy, J. Domagala, J. M. Musser, and K. Drlica. 2000. Selection of antibiotic-resistant bacterial mutants: allelic diversity among fluoroquinolone-resistant mutations. J. Infect. Dis. 182:517-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]