Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the pharmacokinetics and safety of voriconazole after intravenous (i.v.) administration in immunocompromised children (2 to 11 years old) and adults (20 to 60 years old) who required treatment for the prevention or therapy of systemic fungal infections. Nine pediatric patients were treated with a dose of 7 mg/kg i.v. every 12 h for a period of 10 days. Three children and 12 adults received two loading doses of 6 mg/kg i.v. every 12 h, followed by a maintenance dose of 5 mg/kg (children) or 4 mg/kg (adults) twice a day during the entire study period. Trough voriconazole levels in blood over 10 days of therapy and regular voriconazole levels in blood for up to 12 h postdose on day 3 were examined. Wide intra- and interindividual variations in plasma voriconazole levels were noted in each dose group and were most pronounced in the children receiving the 7-mg/kg dose. Five (56%) of them frequently had trough voriconazole levels in plasma below 1 μg/ml or above 6 μg/ml. The recommended dose of 7 mg/kg i.v. in children provides exposure (area under the concentration-time curve) comparable to that observed in adults receiving 4 mg/kg i.v. The children had significantly higher Cmax values; other pharmacokinetic parameters were not significantly different from those of adults. Voriconazole exhibits nonlinear pharmacokinetics in the majority of children. Voriconazole therapy was safe and well tolerated in pediatric and adult patients. The European Medicines Agency-approved i.v. dose of 7 mg/kg can be recommended for children aged 2 to <12 years.

Voriconazole (VRC) is an extended-spectrum triazole antifungal agent structurally derived from fluconazole with activity against a wide variety of yeasts and molds (4, 5, 8-11, 22). The drug is increasingly used in pediatric patients, but only a few studies have reported on the safety and pharmacokinetics of VRC in children (13, 19, 29, 30). These studies showed that there exist important pharmacokinetic differences between adults and children. VRC displays nonlinear pharmacokinetics in adults (14, 24, 25) but has linear pharmacokinetics in children receiving standard adult doses of 3 and 4 mg/kg every 12 h (30). The linearity was based on an 11-patient single-dose study of immunocompromised children (aged 2 to 11 years) and a 28-patient multiple-dose study of two age cohorts (2 to 6 and 6 to 11 years). Exposures were similar at 4 mg/kg in children and 3 mg/kg in adults. This observation likely reflects the higher elimination capacity of pediatric patients due to a greater ratio of liver mass to body mass than that of adults. To avoid clinical failures in children because of potentially subtherapeutic levels, higher per-kilogram doses of the drug are required in children to achieve exposures similar to those achieved in adults (26).

In order to determine a dosing regimen that achieves comparable drug exposure levels in children and adults, a population pharmacokinetic analysis evaluated plasma VRC concentration-time data from a total of 82 patients aged 2 to <12 years. Data from the two above-mentioned studies (single and multiple doses of 3 and 4 mg/kg body weight) and data from a two-cohort, multiple-dose, intravenous (i.v.)-to-oral (p.o.) dosing switch study (4, 6, and 8 mg/kg body weight) were included in the analysis (13). Simulation outcomes suggest that exposure levels achieved with 7 mg/kg i.v. twice a day or 200 mg p.o. twice a day in pediatric patients aged 2 to <12 years are comparable to exposure levels observed in adult patients receiving approved dosing regimens. The dosage difference between adult and pediatric populations is a result of the different degrees of nonlinearity in VRC pharmacokinetics exhibited by the two groups. Due to a higher Michaelis-Menten constant in children than in adults, nonlinear elimination became principally apparent at higher doses for pediatric patients than for adults (13). In 2005, 3 years after preliminary approval by the European Union, new dosing recommendations for children aged 2 to <12 years (7 mg/kg i.v. twice a day or 200 mg p.o. twice a day) were established, despite the fact that this particular dose was not actually tested in the three pharmacokinetic studies that formed the basis of the simulation.

In a retrospective study, a total of 207 VRC concentrations were measured in 46 children aged 0.8 to 20.5 years (19). Most (90%) of them received VRC p.o. (doses of 2.0 to 12.9 mg/kg body weight). Eight children received VRC i.v. (doses of 3.4 to 10.5 mg/kg body weight). Simulations predicted that an i.v. dose of 7 mg/kg or a p.o. dose of 200 mg twice daily would achieve a trough level of >1 μg/ml in most patients, but with a wide range of possible concentrations.

We conducted an open-label, multicenter, parallel-group study to investigate the pharmacokinetics and safety profile of the parenteral formulation of VRC in immunocompromised children (aged 2 to <12 years) with a higher VRC dose per kg body weight than for adults (aged 20 to 60 years) with recommended dosing. We started to determine the plasma pharmacokinetics in pediatric patients with an i.v. dose of 5 mg/kg following the primary study protocol until October 2005 (n = 3) and after that with the newly European Medicines Agency(EMA)-approved i.v. dose of 7 mg/kg (n = 9).

(This study was presented at the 50th annual German Society for Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology conference in Mainz, Germany, on 10 to 12 March 2009 [abstract 460].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical trial.

The study was an open-label, multicenter, parallel-group study of pediatric and adult patients designed to determine the safety and pharmacokinetics of the parenteral formulation of VRC. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their guardians, in the case of minors, before they were enrolled in this study. The trial was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Universities of Leipzig and Halle and conducted in compliance with the 1996 revisions to the Declaration of Helsinki and national and local regulations.

Subjects.

Twelve children and 12 adults (male or female) with hematological malignancies who required treatment for the prevention or therapy of systemic fungal infections were included at Leipzig and Halle hospitals from April 2005 to November 2008. The study patients suffered from multiple comorbidities and received multiple medications. The most commonly prescribed medications prior to study entry and during the study included antibiotics, antivirals, anticancer drugs, diuretics, gastrointestinal drugs, and analgesics. Patients were excluded from the study if they received potent inducers or inhibitors of hepatic enzymes (see inclusion and exclusion criteria). Most of the patients required concomitant VRC and proton pump inhibitor therapy for duodenal and gastric ulcers, erosive esophagitis, or gastroesophageal reflux disease. All of the adult patients and six children concomitantly received the ulcer-healing drug esomeprazole. The effect of omeprazole coadministration with p.o. VRC has been studied before in healthy subjects (31). The steady-state Cmax and area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) of VRC increased by about 15% and 40%, respectively. No VRC dose adjustment was recommended.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Children aged 2 to <12 years and adults aged 20 to <60 years who required treatment for the prevention or therapy of systemic fungal infections were eligible for this study. An invasive fungal infection was classified as proven, probable, or possible according to European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Mycosis Study Group definitions published in 2002 (1). Patients were also eligible for the study when two of the following criteria were fulfilled: (i) persistent fever for >72 h refractory to appropriate broad-spectrum antibacterial treatment, (ii) neutropenia (<500 neutrophils/mm3), (iii) radiological or sonographic evidence of invasive Aspergillus or Candida infection (typical radiologic shadows or a halo sign or air crescent sign on computed tomography), and/or (iv) blood samples positive for Aspergillus or Candida antigen.

Patients were excluded from the study if they were pregnant or lactating or if they were allergic to azole antifungal agents. Patients were ineligible for the study if they had received rifampin, rifabutin, carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, nevirapine, efavirenz, or barbiturates within 14 days prior to study entry because these are potent inducers of hepatic enzymes and would result in undetectable levels of VRC. Patients were also ineligible for the study if they had been receiving or were dependent on the following drugs at least 24 h prior to study entry: terfenadine, cisapride, pimozide, and astemizole (due to the possibility of heart rate-corrected QT interval prolongation); quinidine, ergotamine, sirolimus, saquinavir, amprenavir, nelfinavir, delarvirdine, ritonavir, and sulfonylureas. Patients with severe hypokalemia (below 3.2 mmol/liter) were excluded too, but if their potassium levels could be corrected to >3.2 mmol/liter, the patients were eligible. The following liver function test (LFT) or renal function test abnormalities also led to the exclusion of patients: aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and γ-glutamyltransferase (γ-GT) levels higher than three times the upper limit of normal (ULN); alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and total bilirubin levels higher than two times the ULN, and a creatinine clearance of <60 ml/min. Patients were also ineligible for the study if they had any other condition which, in the opinion of the investigator, would make the patient unsuitable for enrolment.

Treatment.

VRC was supplied as a 10-mg/ml infusate in sulfobutylether-β-cyclodextrin sodium salt for a 1-h i.v. infusion. The patients were divided into three treatment groups. Nine children received a VRC dose of 7 mg/kg i.v. every 12 h (group A, n = 9) over the entire study period. Until October 2005, children were treated following the primary study protocol with two loading doses of 6 mg/kg i.v. every 12 h, followed by a maintenance dose of 5 mg/kg i.v. every 12 h (group B, n = 3). Adults received an i.v. loading dose of 6 mg/kg every 12 h for two doses. I.v. loading doses were followed by an i.v. maintenance dose of 4 mg/kg every 12 h (group C, n = 12).

Plasma pharmacokinetic sampling.

The pharmacokinetics of VRC were determined by analysis of the plasma drug levels obtained throughout the study's duration. Venous blood samples (sufficient to provide a minimum of 0.6 ml of plasma) were collected in lithium heparin tubes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany; 1.2-ml monovette for children and 2.7-ml monovette for adults). On days 2 to 11, the blood samples were collected immediately before the morning infusion (trough levels). On day 3 (steady state), additional blood samples were taken for up to 12 h after the start of the 1-h infusion at the following intervals for the quantification of plasma VRC pharmacokinetics: 1.08, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 8, and 12 h (group A) and 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 8, and 12 h (groups B and C). The blood samples were collected via peripheral lines or via a double-lumen venous catheter after adequate flushing. The samples were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min within 60 min postcollection and stored at −20°C until analysis.

Safety assessments and criteria.

Safety was monitored throughout the study. All adverse events that occurred during treatment were recorded daily. Adverse events were evaluated regarding their severity (mild, moderate, severe, or life threatening). The severity of each adverse event was determined by the clinical staff and study monitor based on direct observation and interview of the subject. Measurements of vital signs (blood pressure and pulse) were conducted daily. Routine clinical laboratory tests and hematology and clinical chemistry analyses were performed with blood samples taken at screening and before the morning dose at least on days 1, 4, 7, and 10.

Analytical methods.

The concentrations of VRC in plasma samples were determined using a high-performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) technique as described previously (17). The method involves the addition of an internal standard (UK-115794), followed by organic solvent extraction from alkaline plasma with n-hexane-ethyl acetate (3:1, vol/vol). Chromatographic separation was carried out with a reversed-phase HPLC column (LUNA 5μ C18 100A, 250 by 3.0 by 5 mm; Phenomenex Aschaffenburg, Germany) protected by a C18 guard column (4 by 2.0 mm; Phenomenex Aschaffenburg, Germany) with a mobile phase consisting of 0.01 M potassium dihydrogen phosphate buffer (containing 0.01 M N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine [TEMED] as a modifier; the pH was adjusted to 6.8 with phosphoric acid) and acetonitrile (55:45, vol/vol). Fluorescence was measured with emission and excitation wavelengths set at 372 and 254 nm, respectively. The assay was linear through a range of 0.1 to 10 μg/ml using a 0.3-ml sample volume. The intra- and interday precision levels were all below 6.1% for plasma. The accuracy percentages ranged from 96% to 108%. The mean percent VRC recovery was 86% ± 4%. The limit of quantitation was set at the lowest calibration standard value (0.1 μg/ml).

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

Pharmacokinetic parameters derived from the concentration data were calculated for each individual subject in each dosing group by the use of noncompartmental methods with the commercially available software WinNonlin (Version 5.2.1; Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA).

Of the plasma concentration-time data on day 3 of therapy, the following pharmacokinetic parameters were included: the maximum drug concentration in plasma (Cmax), the time to the maximum drug concentration in plasma (tmax), the average drug concentration in plasma (Cavg; computed as AUC0-12 h/τ, where τ is the dosing interval), the AUC from 0 to 12 h (AUC0-12 h, calculated by the linear trapezoidal rule), the dose-normalized AUC0-12 h (calculated as AUC0-12 h/dose), the terminal elimination phase rate constant (λz; estimated by log-linear regression analysis using the last three or four data points located on the terminal log-linear phase), the terminal elimination phase half-life (t1/2; calculated as 0.693/λz), the total body clearance at steady state (CLss; calculated as dose/AUC0-12 h), the volume of distribution at steady state (Vss; calculated as mean residence time × CL), and the accumulation index (calculated as 1/[1 − e−(λz·τ)]).

Statistical analysis.

The mean plasma trough levels over 10 days of therapy in all subjects and the mean pharmacokinetic values on day 3 in groups A, B, and C are presented as geometric means (to minimize the effects of extreme values) and ranges. The intra- and interindividual variability of pharmacokinetic values are expressed as percent coefficients of variation (CVs). To compare the AUC0-12 h and the accumulation index between children receiving 7 mg VRC/kg (group A, n = 9) and adults (group C, n = 12), the unpaired t test was used. The Mann-Whitney rank-sum test was used for between-group comparisons of Cmax, CLss, and trough levels. A two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered significant. To assess the correlation between the trough VRC levels in plasma and the levels of AST, ALT, ALP, γ-GT, and total bilirubin in children, as well as in adults, linear regression analysis (least-squares regression) was used. Results are presented as coefficients of determination (R2). All calculations were carried out with SigmaStat 3.5 and Sigma Plot 8.0 (Systat Software GmbH, Erkrath, Germany).

RESULTS

Patient demographics.

The children were aged 2 to 11 years with a mean age of 7 years, and the adults were aged 25 to 58 years with a mean age of 44 years. All patients had serious underlying conditions, including hematologic malignancy, and undergoing allogeneic or autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. At baseline, neutropenia (<500 × 106 cells/liter) was observed in 11 children and 7 adults. Twenty-two subjects completed the study and were fully evaluable. One adult and one child (group B) discontinued participation in the study on day 9 due to a clinically significant elevation of bilirubin (more than four times the ULN; adult) and discharge from the hospital (child), respectively. The pharmacokinetic analysis was based on 477 samples obtained from 24 subjects: the 12 pediatric subjects (a total of 229 samples) and the 12 adults (a total of 248 samples). Table 1 shows the patients' characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 24 patients in this study

| Characteristic | Children (n = 12) | Adults (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age, yr (range) | 6.8 (2-11) | 44.2 (25-58) |

| Mean body wt, kg (range) | 24.2 (13-41) | 79.8 (61-111) |

| No. of males/females | 8/4 | 8/4 |

| No. of VCR plasma specimens | 229 | 248 |

| Median no. of plasma levels per patient (range) | 19 (18-22) | 20 (19-22) |

| No. with following indications for VCR therapy: | ||

| Prophylaxis | 1 | 5 |

| Therapy | 11 | 7 |

| Possible invasive fungal infection | 1 | 2 |

| Neutropenia at baseline | 11 | 7 |

| Persistent fever during neutropenia | 10 | 1 |

| No. with following underlying conditions: | ||

| Leukemia | 8 | 7 |

| Lymphoma | 1 | 5 |

| Blastoma | 2 | |

| Solid tumor | 1 | |

| No. with following types of transplant: | ||

| Allograft | 1 | |

| Autograft | 4 | |

| No. with adverse event leading to discontinuation of therapy | 1 |

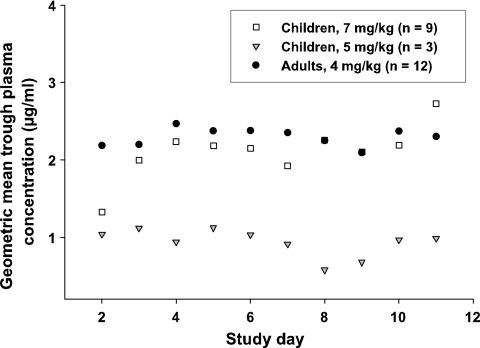

Plasma trough levels over 10 days.

The trough concentrations ranged from <0.1 to 16.3 μg/ml in children and from 0.3 to 9.5 μg/ml in adults. The plasma trough levels in children receiving the EMA-approved i.v. dose of 7 mg/kg were not significantly different from the values obtained in adults receiving a dose of 4 mg/kg i.v. (geometric mean plasma trough concentrations, 2.2 μg/ml versus 2.3 μg/ml, respectively, P = 0.056). The average values for trough levels in children with a VRC dose of 5 mg/kg were substantially lower than the values obtained in the other two groups (geometric mean plasma trough concentration, 0.9 μg/ml). Figure 1 illustrates the mean plasma trough levels over 10 days of therapy in children (group A and B) and adults (group C). Visual inspection of the trough level data suggested that a steady state was reached on day 2 in adults and on day 3 in children (group A). The administration of a loading dose to adults accounts for the quicker achievement of steady-state plasma trough values.

FIG. 1.

Geometric mean trough concentrations of VRC in plasma of children and adults over 10 days of therapy.

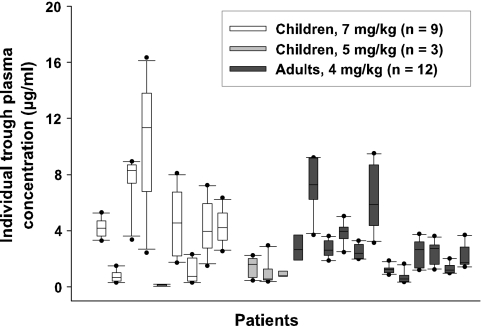

Trough concentrations varied substantially over the study period in some patients (CV ranges: group A, 15 to 72%; group B, 33 to 91%; group C, 20 to 61%). The individual trough VRC concentrations in plasma over 10 days of therapy in all of the patients are illustrated in Fig. 2. For example, patient 4, a 3-year-old child suffering from acute leukemia, showed an initial trough VRC level of 2.4 μg/ml (day 2), which rose progressively to 16.3 μg/ml (day 8) and fell back to 11.7 μg/ml (day 11) (CV, 41%). Variations in plasma trough levels between patients were also substantial in all dosage groups (CVs: group A, 87%; group B, 63%; group C, 73%).

FIG. 2.

Box plot of VRC trough levels in 24 patients over 10 days of therapy (thick bar, median level; box, interquartile range; whiskers, minimum and maximum levels; dot, outlier).

Three children in group A, all of the children in group B, and three adults showed plasma trough levels below 1.0 μg/ml. Plasma trough levels above 6.0 μg/ml occurred in five children in group A and in two adults. Very low and potentially subtherapeutic levels of VRC were detected in a 2-year-old child suffering from acute myeloid leukemia (patient 5), which was treated with 7 mg/kg i.v. every 12 h. The plasma trough concentrations ranged from <0.1 to 0.16 μg/ml over the study period. The child received VRC to prevent an invasive fungal infection. No breakthrough fungal infection was recorded.

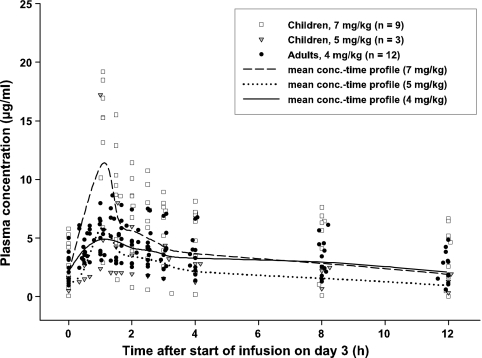

Pharmacokinetic parameters on day 3.

Figure 3 shows the individual and geometric mean plasma concentration-time profiles of VRC in children and adults on day 3. In the majority of the subjects, the maximum plasma VRC concentrations generally occurred at the end of the 1-h infusion and ranged from 2.4 to 19.2 μg/ml in children and from 3.1 to 7.5 μg/ml in adults. The geometric mean maximum and average plasma VRC concentrations in children receiving doses of 7 mg/kg i.v. (group A) were higher than those of adult patients receiving 4 mg/kg (mean Cmax, 11.4 versus 5.4 μg/ml; mean Cavg, 4.1 versus 3.2 μg/ml, respectively). There was a statistically significant difference in the Cmax levels (P = 0.012). The pharmacokinetic parameters are listed in Table 2 .

FIG. 3.

Individual and geometric mean concentration-time profiles of VRC in plasma of children and adults on day 3.

TABLE 2.

Individual and mean pharmacokinetic parameters on day 3 and plasma trough levels over 10 days of therapy in children and adultsa

| Patient no. or group | VRC dose (mg/kg) | Genderb | Age (yr) | Trough level (μg/ml) over 10 days (range) | Cmax (μg/ml) | tmax (h) | Cavg (μg/ml) | AUC0-12h (μg·h/ml) | t1/2 (h) | Vss (ml/kg) | CLss (ml/h/kg) | Accumulation index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | M | 7.8 | 4.16 (3.3-5.3) | 10.1 | 1.0 | 6.7 | 80.7 | 13.3 | 1,594 | 87.1 | 2.1 |

| 2 | 7 | F | 5.8 | 0.64 (0.3-1.5) | 13.1 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 28.2 | 3.7 | 953 | 248.3 | 1.1 |

| 3 | 7 | M | 10.9 | 7.40 (3.4-8.9) | 19.2 | 1.1 | 8.9 | 106.6 | 21.2 | 1,816 | 65.7 | 3.1 |

| 4 | 7 | F | 3.3 | 9.18 (2.4-16.3) | 15.3 | 1.1 | 7.8 | 94.0 | 29.2 | 2,947 | 74.5 | 4.0 |

| 5 | 7 | F | 2.3 | >0.1 (0-0.2) | 2.9 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 4.7 | 3.1 | 3,311 | 1,483.1 | 1.1 |

| 6 | 7 | M | 7.8 | 3.92 (1.7-8.1) | 16.9 | 1.1 | 7.3 | 87.4 | 16.9 | 1,770 | 80.1 | 2.6 |

| 7 | 7 | F | 10.2 | 0.87 (0.3-2.3) | 5.9 | 1.1 | 3.1 | 36.9 | 7.7 | 1,987 | 189.5 | 1.5 |

| 8 | 7 | M | 7.8 | 3.88 (1.5-7.2) | 18.5 | 1.1 | 5.3 | 63.1 | 9.1 | 1,166 | 110.9 | 1.7 |

| 9 | 7 | M | 5.2 | 4.06 (2.5-6.3) | 15.2 | 1.1 | 6.6 | 79.1 | 20.1 | 2,322 | 88.4 | 2.9 |

| 10 | 5 | M | 7.9 | 1.19 (0.4-2.2) | 4.8 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 33.9 | 14.6 | 2,871 | 148.1 | 2.3 |

| 11 | 5 | M | 7.1 | 0.75 (0.4-3.0) | 2.4 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 12.6 | 4.2 | 2,240 | 396.8 | 1.2 |

| 12 | 5 | M | 5.7 | 0.90 (0.7-1.6) | 17.2 | 1.0 | 3.5 | 41.5 | 7.2 | 902 | 120.5 | 1.5 |

| 13 | 4 | F | 41.9 | 2.52 (1.1-4.2) | 7.3 | 2.6 | 5.2 | 62.5 | 6.9 | 675 | 63.9 | 1.4 |

| 14 | 4 | M | 45.3 | 6.99 (3.7-9.2) | 8.6 | 1.4 | 6.3 | 76.0 | 17.7 | 1,293 | 52.6 | 2.7 |

| 15 | 4 | F | 49.3 | 2.68 (1.9-3.6) | 3.1 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 28.2 | 18.8 | 3,775 | 141.8 | 2.8 |

| 16 | 4 | F | 58.3 | 3.73 (2.5-5.0) | 7.5 | 1.3 | 3.7 | 44.8 | 28.1 | 3,321 | 89.3 | 3.9 |

| 17 | 4 | M | 50.7 | 2.44 (2.0-3.3) | 6.2 | 1.0 | 4.8 | 57.0 | 45.7 | 4,047 | 69.8 | 6.0 |

| 18 | 4 | M | 37.3 | 5.91 (3.1-9.5) | 6.7 | 1.3 | 4.8 | 57.2 | 24.2 | 2,503 | 69.5 | 3.4 |

| 19 | 4 | M | 33.3 | 1.20 (0.9-1.9) | 3.8 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 24.7 | 8.4 | 1,714 | 162.3 | 1.6 |

| 20 | 4 | M | 33.5 | 0.58 (0.3-1.6) | 3.9 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 18.2 | 7.3 | 1,793 | 218.6 | 1.5 |

| 21 | 4 | M | 46.4 | 2.19 (1.2-3.8) | 6.5 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 47.5 | 18.4 | 1,999 | 83.3 | 2.8 |

| 22 | 4 | M | 57.3 | 2.30 (1.2-3.6) | 4.9 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 28.2 | 13.9 | 2,430 | 139.2 | 2.2 |

| 23 | 4 | F | 25.1 | 1.25 (1.0-2.0) | 4.3 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 26.3 | 6.9 | 1,422 | 151.9 | 1.4 |

| 24 | 4 | M | 52.5 | 2.03 (1.4-3.7) | 5.3 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 36.4 | 9.0 | 1,342 | 110.0 | 1.7 |

| Children | 7 | 6.8c (2.3-10.9) | 2.16 (0.0-16.3)d | 11.4 (2.9-19.2) | 1.1 (1.0-1.1) | 4.1 (0.4-8.9) | 49.3 (4.7-106.6) | 10.9 (3.1-29.2) | 1,852 (953-3,311) | 141.9 (65.7-1,483.1) | 2.0 (1.1-4.0) | |

| Children | 5 | 6.9c (5.1-7.9) | 0.93 (0.4-3.0)e | 5.8 (2.4-17.2) | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) | 2.2 (1.1-3.5) | 26.1 (12.6-41.5) | 7.7 (4.2-14.6) | 1,796 (902-2,871) | 192.1 (120.5-396.8) | 1.6 (1.2-2.3) | |

| Adults | 4 | 44.2c (25.1-58.3) | 2.30 (0.3-9.5)f | 5.4 (3.1-8.6) | 1.1 (0.5-2.6) | 3.2 (1.5-6.3) | 38.7 (18.2-76.0) | 14.3 (6.9-45.7) | 1,957 (675-4,047) | 103.0 (52.6-218.6) | 2.4 (1.4-6.0) |

All mean values are geometric means, except those marked by footnote c.

M, male; F, female.

Arithmetic mean.

n = 89.

n = 28.

n = 118.

The AUC0 to 12 h values ranged from 4.7 to 106.6 μg·h/ml in children and from 18.2 to 76.0 μg·h/m in adults. The geometric mean AUC of pediatric patients with a VRC dose of 7 mg/kg was higher than that of adults, but the difference was not statistically significant (AUC0 to 12 h, 49.3 versus 38.7 μg·h/ml, respectively; P = 0.068). The average AUCs of children with a VRC dose of 5 mg/kg were substantially lower than the values obtained in the other two groups (geometric mean AUC0 to 12 h, 26.1 μg·h/ml).

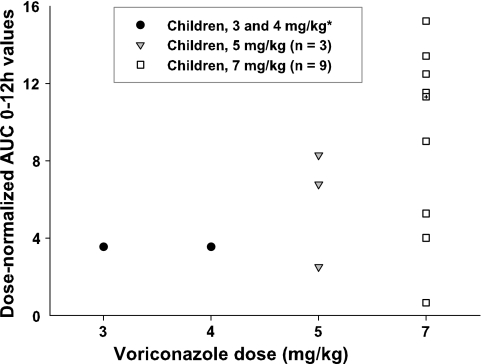

In each dose group, wide interindividual AUC variations were noted, with the CVs ranging from 43% in adults to 53% in children. Figure 4 shows the individual dose-normalized AUCs (AUC0 to 12 h/dose) on day 3 for VRC in children with 5 and 7 mg/kg i.v., as well as the dose-normalized median AUCs in children with 3 and 4 mg/kg i.v. (data from reference 30). We observed an increase in the dose-normalized AUCs in seven children with the 7-mg/kg dose (range, 1.5- to 4.3-fold increases) and in two children with the 5-mg/kg dose (range, 1.9- to 2.3-fold increases). Trough concentrations ranged from 1.6 to 5.8 μg/ml (day 3) in these children, and the degree of nonlinearity was dependent on the plasma VRC level. The plasma trough levels in the other three children (patients 2, 5, and 11) were below 0.8 μg/ml (day 3). Compared to the children receiving doses of 3 and 4 mg/kg, no higher-than-proportional increase in exposure was observed in these three children.

FIG. 4.

Individual dose-normalized AUCs (AUC0-12 h/dose) of VRC in children receiving 5 and 7 mg/kg i.v. and dose-normalized median AUCs in children receiving 3 and 4 mg/kg i.v. (*, data from reference 30; +, dose-normalized median AUC in children receiving 7 mg/kg i.v.).

Body weight-normalized VRC clearance in children with 7 mg/kg i.v. exceeded that in adults (geometric mean CLss, 142 versus 103 ml/h/kg), but the values did not differ significantly (P = 0.594). The accumulation of VRC was at the highest level in adults, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.493). Interindividual variability was 170% for CLss, 64% for t1/2, and 39% for Vss in children (group A) and 45% for CLss, 67% for t1/2, and 48% for Vss in adults.

Adverse events.

Adverse reactions during the study period were usually mild to moderate and occurred less frequently in children. The most commonly reported adverse events included visual, digestive tract, and neurological events and hepatic abnormalities (Table 3). Two children and four adults experienced at least one adverse visual event. A total of 35 cases of possibly drug-related visual disturbance (enhanced/altered visual perception, blurred vision, abnormal color vision, and abnormal brightness of vision) were reported in these subjects.

TABLE 3.

Adverse events during VRC therapy in 24 patients

| Type of event | No. of children with dose of: |

No. of adults with dose of 4 mg/kg (n = 12) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 mg/kg (n = 9) |

5 mg/kg (n = 3) |

|||||

| 1-2a | 3-4 | 1-2 | 3-4 | 1-2 | 3-4 | |

| Visual | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Digestive tract | ||||||

| Diarrhea | 3 | 1 | 8 | 1 | ||

| Vomiting | 7 | 2 | 5 | 2 | ||

| Nausea | 3 | 1 | 7 | 2 | ||

| Neurologic | ||||||

| Headache | 2 | 3 | 3 | |||

| Confusion | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Hepatic | ||||||

| AST level ≥2.5 times ULN | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| ALT level ≥2.5 times ULN | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| γ-GT level ≥2.5 times ULN | 3 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 2 | |

| ALP level ≥2.5 times ULN | 2 | |||||

| Bilirubin level ≥1.5 times ULN | 3 | |||||

Severity levels: 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe; 4, life threatening.

A 37-year-old man suffering from Hodgkin's disease (patient 17) and a 50-year-old man suffering from multiple myeloma (patient 18) experienced confusion during VRC therapy. The geometric mean trough levels in these two adults over 10 days of therapy were 2.4 and 5.9 μg/ml, respectively.

Nine children and 11 adults developed abnormal liver functions (AST, ALT, γ-GT, or ALP levels ≥2.5 times the ULN or bilirubin levels ≥1.5 times the ULN) during study therapy. We did not detect a strong correlation between VRC concentrations and LFT levels in children (R2 values: AST, 0.07; ALT, 0.0; ALP, 0.09; bilirubin, 0.11; γ-GT, 0.38) and adults (R2 values: AST, 0.10; ALT, 0.05; ALP, 0.15; bilirubin, 0.02; γ-GT, 0.04).

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the pharmacokinetics and safety profile of the parenteral formulation of VRC in immunocompromised children (aged 2 to <12 years) receiving a higher VRC dose than adults (aged 20 to 60 years). To our knowledge, this paper is the first to describe intensive pharmacokinetic data on children receiving the EMA-approved i.v. dose of 7 mg/kg.

There are very limited concentration-effect data on VRC in children, and an efficient and safe therapeutic range of VRC doses is still under debate. On the basis of currently available data, Brüggemann et al. (3) suggested the use of a therapeutic range of 1 to 6 μg/ml for VRC plasma trough concentrations. Pascual et al. (20) reported that a lack of response was more frequently observed in patients with drug levels below 1 μg/ml. In a retrospective study of children (aged 0.8 to 20.5 years), a pharmacodynamic association between a VRC trough level of >1 μg/ml and survival was found (19).

The geometric mean plasma trough concentrations were above the in vitro MICs for most fungal pathogens in children receiving the EMA-approved i.v. dose of 7 mg/kg and also in adults (2.2 and 2.3 μg/ml, respectively). However, three children (patients 2, 5, and 7) and one adult (patient 20) frequently showed plasma trough levels below 1 μg/ml. Low plasma trough concentrations were also observed in all three children who were treated with a VRC dose of 5 mg/kg. Two children (patients 3 and 4) and two adults (patients 14 and 18) frequently showed plasma trough levels above 6 μg/ml. The higher plasma drug levels in children were not related to the occurrence of further side effects, but the small number of pediatric patients (n = 12) does not allow one to draw definite conclusions.

VRC therapy was safe and well tolerated in pediatric and adult patients. The most commonly reported adverse events in children and adults included visual, digestive tract, and neurological events and hepatic abnormities. The frequency of abnormal LFT results was relatively high; however, the events were mostly mild to moderate in severity and only in the case of one adult (patient 13) did they lead to the discontinuation of VRC therapy after 9 days of treatment due to a clinically significant elevation of the serum bilirubin level (more than four times the ULN). In accordance with the results of previous studies (15, 27), we did not detect a strong correlation between VRC concentrations and LFT levels. The occurrence of confusion during VRC therapy might be more frequent in the presence of higher VRC levels (2, 12, 20, 32). Two adults (patients 17 and 18) became confused during VRC therapy. Their geometric mean trough levels over the study therapy period were 2.4 and 5.9 μg/ml, respectively.

It is known that VRC exhibits nonlinear pharmacokinetics in adults due to saturation of its metabolism with a higher-than-proportional increase in exposure observed with an increasing dose (14, 23-25). In contrast to adults, children showed linear elimination after multiple 3- and 4-mg/kg i.v. doses (30). Compared to the values obtained in the children receiving a 3- or 4-mg/kg dose, the increases in the trough levels and AUCs in most of the children with an i.v. dose of 7 mg/kg were higher than proportional. Our data indicate that VRC exhibits nonlinear pharmacokinetics in the majority of children treated with an i.v. dose of 7 mg/kg, possibly due to the saturation of its metabolism, as is the case in adults.

VRC is characterized by a wide intra- and interindividual variability in drug exposure (AUC). An approximately 100-fold interpatient variability has been reported for the antifungal agent (6). We measured the trough levels in 12 children and 12 adults during 10 days of therapy. The drug was administered i.v. every 12 h, and the dose was based on bodyweight. We can therefore exclude VRC variability due to variable absorption of the drug, different dosing per kilogram of body weight, and different times of level checking. Nevertheless, we observed a large intra- and interindividual variability in the pharmacokinetics of VRC in children and adults. This may be due to many factors, such as gender, age, different degrees of nonlinearity in the pharmacokinetics of VRC in different individuals, variable metabolism due to genetic polymorphism or elimination capacity, and/or drug interactions. The highest level of variability in the pharmacokinetic parameters was observed in the children receiving 7-mg/kg doses. The interpatient variability of trough levels in children and adults over 10 days of therapy was 87- and 73-fold, respectively, in our study. In both groups, we found the lowest level of variability of the trough levels on day 2 (CVs: children, 55%; adults, 33%), while the highest variability was reported on day 8 (CVs: children, 104%; adults, 88%).

Depending on the high variability of VRC, the optimal dose of VRC may differ significantly from one child to another. In a report by Destino et al. (7), doses as high as 13.4 mg/kg every 12 h were required to obtain trough concentrations of 0.2 μg/ml in a 4-year-old boy. We found plasma trough concentrations as low as <0.1 μg/ml and as high as 16.3 μg/ml in a 2- and a 3-year-old girl, respectively. Both were treated with the EMA-approved i.v. dose of 7 mg/kg.

We suppose that the occurrence of low plasma drug levels will be even more pronounced in pediatric patients 2 to <12 years of age who are treated p.o. with the recommended dose of 200 mg VRC twice a day, since oral bioavailability is dependent on meals and moreover, compared to adults, it is reduced in children (13, 19). Simulations predict that the EMA-approved i.v. dose of 7 mg/kg will achieve a trough level above 1 μg/ml in >50% of children, but the EMA-approved p.o. dose of 200 mg twice a day, which applies to all ages, will achieve this target level in only 25 to 50% of children (18).

Large variations in VRC pharmacokinetics may be associated with decreased efficacy or with toxicity (20). Therapeutic drug monitoring of VRC levels should be considered, especially in pediatric patients (21). It has been demonstrated that in patients with invasive mycoses, therapeutic VRC monitoring and individualized dose adjustments could improve the efficacy and safety outcomes (20). In the guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of aspergillosis published in 2008, the measurement of serum drug levels, especially in patients receiving oral therapy, is recommended for some patients, either to monitor for potential toxicity or to document adequate drug exposure, especially in progressive infection (28). Recently, we demonstrated that monitoring of VRC in saliva is a useful and suitable alternative to the monitoring of plasma drug levels (16). Especially in pediatric and ambulatory patients, when blood drawing is difficult, salivary monitoring may play an important role because the collection of saliva is an easy, noninvasive, and painless procedure and can be carried out by the patient or by his or her parent.

In conclusion, the present study contributes to the limited knowledge of the pharmacokinetic properties and safety of VRC in children 2 to <12 years old who received the EMA-approved i.v. dose of 7 mg/kg. VRC was well tolerated by both pediatric and adult patients. We showed that nonlinear pharmacokinetics were apparent in most of the children following doses of 7 mg/kg, possibly due to saturation of VRC metabolism. The recommended dose of 7 mg/kg in children provides exposure (AUC) comparable to that observed in adults. The pharmacokinetic parameters in these children were not significantly different from the values obtained in adults receiving a maintenance dose of 4 mg/kg i.v., with the exception of significantly higher Cmax values in children. Intra- and interpatient variability in the plasma VRC levels in children and adults was generally high and most pronounced in children. Based on the observed variability, therapeutic monitoring of VRC levels should be considered, especially in pediatric patients. The results of this study suggest that a VRC dose of 7 mg/kg i.v. can be recommended for children aged 2 to <12 years.

Acknowledgments

Financial support and the drug for this study were provided by Pfizer Pharma GmbH (Berlin, Germany) and are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ascioglu, S., J. H. Rex, B. de Pauw, J. E. Bennett, J. Bille, F. Crokaert, D. W. Denning, J. P. Donnelly, J. E. Edwards, Z. Erjavec, D. Fiere, O. Lortholary, J. Maertens, J. F. Meis, T. F. Patterson, J. Ritter, D. Selleslag, P. M. Shah, D. A. Stevens, and T. J. Walsh. 2002. Defining opportunistic invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients with cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplants: an international consensus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:7-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd, A. E., S. Modi, S. J. Howard, C. B. Moore, B. G. Keevil, and D. W. Denning. 2004. Adverse reactions to voriconazole. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:1241-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brüggemann, R. J. M., J. P. Donnelly, R. E. Aarnoutse, A. Warris, N. M. A. Blijlevens, J. W. Mouton, P. E. Verweij, and D. M. Burger. 2008. Therapeutic drug monitoring of voriconazole. Ther. Drug Monit. 30:403-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clancy, C. J., and M. H. Nguyen. 1998. In vitro efficacy and fungicidal activity of voriconazole against Aspergillus and Fusarium species. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 17:573-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuenca-Estrella, M., J. R. Rodríguez-Tudela, E. Mellado, J. V. Martínez-Suárez, and A. Monzón. 1998. Comparison of the in-vitro activity of voriconazole (UK-109,496), itraconazole and amphotericin B against clinical isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 42:531-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denning, D. W., P. Ribaud, N. Milpied, D. Caillot, R. Herbrecht, E. Thiel, A. Haas, M. Ruhnke, and H. Lode. 2002. Efficacy and safety of voriconazole in the treatment of acute invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:563-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Destino, L., D. A. Sutton, A. L. Helon, P. L. Havens, J. G. Thometz, R. E. Willoughby, Jr., and M. J. Chusid. 2006. Severe osteomyelitis caused by Myceliophthora thermophila after a pitchfork injury. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 5:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espinel-Ingroff, A. 1998. In vitro activity of the new triazole voriconazole (UK-109,496) against opportunistic filamentous and dimorphic fungi and common and emerging yeast pathogens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:198-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espinel-Ingroff, A., E. Canton, D. Gibbs, and A. Wang. 2007. Correlation of Neo-Sensitabs tablet diffusion assay results on three different agar media with CLSI broth microdilution M27-A2 and disk diffusion M44-A results for testing susceptibilities of Candida spp. and Cryptococcus neoformans to amphotericin B, caspofungin, fluconazole, itraconazole, and voriconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:858-864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espinel-Ingroff, A., K. Boyle, and D. J. Sheehan. 2001. In vitro antifungal activities of voriconazole and reference agents as determined by NCCLS methods: review of the literature. Mycopathologia 150:101-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.George, D., P. Miniter, and V. T. Andriole. 1996. Efficacy of UK-109496, a new azole antifungal agent, in an experimental model of invasive aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:86-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imhof, A., D. J. Schaer, U. Schanz, and U. Schwarz. 2006. Neurological adverse events to voriconazole: evidence for therapeutic drug monitoring. Swiss Med. Wkly. 136:739-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlsson, M. O., I. Lutsar, and P. A. Milligan. 2009. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of voriconazole plasma concentration data from pediatric studies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:935-944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarus, H. M., J. L. Blumer, S. Yanovich, H. Schlamm, and A. Romero. 2002. Safety and pharmacokinetics of oral voriconazole in patients at risk of fungal infection: a dose escalation study. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 42:395-402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lutsar, I., M. R. Hodges, K. Tomaszewski, P. F. Troke, and N. D. Wood. 2003. Safety of voriconazole and dose individualization. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:1087-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michael, C., U. Bierbach, K. Frenzel, T. Lange, N. Basara, D. Niederwieser, C. Mauz-Körholz, and R. Preiss. 2010. Determination of saliva trough levels for monitoring voriconazole therapy in immunocompromised children and adults. Ther. Drug Monit. 32:194-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michael, C., J. Teichert, and R. Preiss. 2008. Determination of voriconazole in human plasma and saliva using high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 865:74-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neely, M., T. Rushing, A. Kovacs, R. Jelliffe, and J. Hoffman. 2009. Voriconazole population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in children, abstr, 1488, p. 18. In Abstracts of the Annual Meeting of the Population Approach Group in Europe. http://www.page-meeting.org/default.asp?abstract=1488.

- 19.Neely, M., T. Rushing, A. Kovacs, R. Jelliffe, and J. Hoffman. 2010. Voriconazole pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:27-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pascual, A., T. Calandra, S. Bolay, T. Buclin, J. Bille, and O. Marchetti. 2008. Voriconazole therapeutic drug monitoring in patients with invasive mycoses improves efficacy and safety outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:201-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasqualotto, A. C., M. Shah, R. Wynn, and D. W. Denning. 2008. Voriconazole plasma monitoring. Arch. Dis. Child. 93:578-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perfect, J. R., K. A. Marr, T. J. Walsh, R. N. Greenberg, B. Dupont, J. Torre-Cisneros, G. Just-Nubling, H. T. Schlamm, I. Lutsar, A. Espinel-Ingroff, and E. Johnson. 2003. Voriconazole treatment for less-common, emerging, or refractory fungal infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:1122-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Purkins, L., N. Wood, K. Greenhalgh, D. E. Malcolm, D. O. Stuart, and D. Nichols. 2003. The pharmacokinetics and safety of intravenous voriconazole—a novel wide-spectrum antifungal agent. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 56:2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purkins, L., N. Wood, K. Greenhalgh, M. J. Allen, and S. D. Oliver. 2003. Voriconazole, a novel wide-spectrum triazole: oral pharmacokinetics and safety. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 56:10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purkins, L., N. Wood, P. Ghahramani, K. Greenhalgh, M. J. Allen, and D. Kleinermans. 2002. Pharmacokinetics and safety of voriconazole following intravenous- to oral-dose escalation regimens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2546-2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinbach, W. J., and D. K. Benjamin. 2005. New antifungal agents under development in children and neonates. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 18:484-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan, K., N. Brayshaw, K. Tomaszewski, P. Troke, and N. Wood. 2006. Investigation of the potential relationships between plasma voriconazole concentrations and visual adverse events or liver function test abnormalities. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 46:235-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsh, T. J., E. J. Anaissie, D. W. Denning, R. Herbrecht, D. P. Kontoyiannis, K. A. Marr, V. A. Morrison, B. H. Segal, W. J. Steinbach, D. A. Stevens, J. van Burik, J. R. Wingard, and T. F. Patterson. 2008. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:327-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh, T. J., I. Lutsar, T. Driscoll, B. DuPont, M. Roden, P. Gharamani, M. Hodges, A. H. Groll, and J. R. Perfect. 2002. Voriconazole in the treatment of aspergillosis, scedosporiosis, and other invasive fungal infections in children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 21:240-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh, T. J., M. O. Karlsson, T. Driscoll, A. G. Arguedas, P. Adamson, X. Saez-Llorens, A. J. Vora, A. C. Arrieta, J. Blumer, I. Lutsar, P. Milligan, and N. Wood. 2004. Pharmacokinetics and safety of intravenous voriconazole in children after singe- or multiple-dose administration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2166-2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wood, N., K. Tan, L. Purkins, G. Layton, J. Hamlin, D. Kleinermans, and D. Nichols. 2003. Effect of omeprazole on the steady-state pharmacokinetics of voriconazole. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 56:56-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zonios, D. I., J. Gea-Banacloche, R. Childs, and J. E. Bennett. 2008. Hallucinations during voriconazole therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47:e7-e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]