Abstract

Most Burkholderia pseudomallei strains are intrinsically aminoglycoside resistant, mainly due to AmrAB-OprA-mediated efflux. Rare naturally occurring or genetically engineered mutants lacking this pump are aminoglycoside susceptible despite the fact that they also encode and express BpeAB-OprB, which was reported to mediate efflux of aminoglycosides in the Singapore strain KHW. To reassess the role of BpeAB-OprB in B. pseudomallei aminoglycoside resistance, we used mutants overexpressing or lacking this pump in either AmrAB-OprA-proficient or -deficient strain 1026b backgrounds. Our data show that BpeAB-OprB does not mediate efflux of aminoglycosides but is a multidrug efflux system which extrudes macrolides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, acriflavine, and, to a lesser extent, chloramphenicol. Phylogenetically, BpeAB-OprB is closely related to Pseudomonas aeruginosa MexAB-OprM, which has a similar substrate spectrum. AmrAB-OprA is most closely related to MexXY, the only P. aeruginosa efflux pump known to extrude aminoglycosides. Since BpeAB-OprB in strain KHW was also implicated in playing a major role in export of acylated homoserine lactone (AHL) quorum-sensing molecules and in expression of diverse virulence factors, we explored whether this was also true in the strain 1026b background. The results showed that BpeAB-OprB was not required for AHL export, and mutants lacking this efflux system exhibited normal swimming motility and siderophore production, which were severely impaired in KHW bpeAB-oprB mutants. Biofilm formation was impaired in 1026b Δ(amrRAB-oprA) and Δ(amrRAB-oprA) Δ(bpeAB-oprB) mutants. At present, we do not know why our BpeAB-OprB susceptibility and virulence factor expression results with 1026b and its derivatives are different from those previously published for Singapore strain KHW.

Efflux pumps of the resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) family play a pivotal role in intrinsic and acquired drug resistance of many Gram-negative pathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa (reviewed in references 19 and 30), Acinetobacter baumannii (11, 40), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (46, 47), and others. Burkholderia pseudomallei is the etiologic agent of melioidosis (6, 42), a rare but serious disease endemic to Southeast Asia, Northern Australia, and other parts of the tropics around the world (10). Treatment of melioidosis is challenging (43) and is complicated by the bacterium's intrinsic antibiotic resistance. Although genome analysis revealed numerous antibiotic resistance mechanisms (16), they have not yet been well studied. The genomes of strain K96243 and other sequenced strains encode at least 10 RND pumps (16, 18). Of these, only two have been characterized in detail. AmrAB-OprA of strain 1026b was shown to confer high-level resistance to aminoglycosides and macrolides (27). BpeAB-OprB of strain KHW was reported to mediate efflux of aminoglycosides and macrolides (5) as well as to play an important role in virulence and quorum sensing (3, 4). Specifically, BpeAB-OprB was shown to mediate efflux of the aminoglycosides gentamicin and streptomycin, the macrolide erythromycin, and the dye acriflavine (5). In strain KHW, this pump is also required for optimal production of biofilms, siderophores, and phospholipase C (4). Finally, excretion of acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) quorum-sensing molecules is dependent on BpeAB-OprB function (3, 4). Using a surrogate P. aeruginosa strain, we recently showed that a third pump, BpeEF-OprC, mediates efflux of chloramphenicol and trimethoprim (17), and its properties in B. pseudomallei are currently being studied in our laboratory. During these studies, we noticed that a 1026b derivative missing AmrAB-OprA was aminoglycoside susceptible, despite the fact that it expressed BpeAB-OprB. Since this finding is contrary to what was previously published about this pump in strain KHW, we decided to study the expression and antibiotic resistance profile of this pump in strain 1026b, using defined mutants. Our results indicate that in strain 1026b, BpeAB-OprB does not mediate efflux of aminoglycosides but extrudes other antibiotics, including fluoroquinolones, clindamycin, macrolides, and tetracyclines. Of these, doxycycline is of therapeutic importance for melioidosis. Strain 1026b BpeAB-OprB mutants were not impaired in extrusion of AHLs, swimming motility, or siderophore production, but AmrAB-OprA BpeAB-OprB mutants were impaired in biofilm formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

Escherichia coli DH5α (21) was used for routine cloning experiments. Other bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were routinely grown at 37°C in Luria broth, Lennox (LB) (34), or on LB agar purchased from Mo Bio Laboratories (Carlsbad, CA). Casamino Acids (CAA) medium contained 0.5% CAA (Difco Laboratories, Livonia, MI) and 0.4 mM MgCl2 in water and was prepared as previously described (35). Deferrated CAA medium was prepared by Chelex-100 (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) treatment (35). Strains containing temperature-sensitive (Ts) plasmid derivatives or Ts alleles were grown at 30°C (permissive temperature) or 42°C (nonpermissive temperature). Antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 15 μg/ml gentamicin, 35 μg/ml kanamycin, and 25 μg/ml zeocin for E. coli; and 1,000 μg/ml kanamycin and 2,000 μg/ml zeocin for wild-type B. pseudomallei. For Δ(amrRAB-oprA) B. pseudomallei efflux pump mutants, gentamicin, kanamycin, and zeocin were used at 15 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml, and 100 μg/ml, respectively. Antibiotics were purchased from the following manufacturers: carbenicillin was from Duchefa Biochemie via Gold Biotechnology, St. Louis, MO; ciprofloxacin was from LKT Laboratories, St. Paul, MN; gentamicin was from EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA; spectinomycin was from Miomol Research Laboratories via VWR International, West Chester, PA; zeocin was from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; and all others were from Sigma, St. Louis, MO.

TABLE 1.

B. pseudomallei strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or propertiesa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| B. pseudomallei strains | ||

| 1026b | Wild-type strain; clinical isolate | 12 |

| Bp50 | 1026b with Δ(amrRAB-oprA)::FRT | 7 |

| Bp58 | Bp50 with ΔbpeR::FRT | This study |

| Bp173 | Bp58 with mini-Tn7T | This study |

| Bp174 | Bp58 with mini-Tn7T-bpeR+ | This study |

| Bp175 | Bp58 with mini-Tn7T-P1-bpeR+ | This study |

| Bp207 | Bp50 with Δ(bpeAB-oprB)::FRT | This study |

| Bp216 | Bp207 with mini-Tn7T | This study |

| Bp227 | 1026b with Δ(bpeAB-oprB)::FRT | This study |

| Bp250 | Bp207 with mini-Tn7T-bpeA+B+-oprB+ | This study |

| Bp340 | 1026b with Δ(amrRAB-oprA) | This study |

| Bp400 | Bp227 with Δ(amrRAB-oprA) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| p34E-Tp1 | Apr Tpr; source of P1 promoter | 13 |

| pEXKm5 | Kmr; allele replacement vector optimized for Burkholderia spp. | 22 |

| pWSK29 | Apr; low-copy-number cloning vector | 41 |

| pUC18T-mini-Tn7T-Km-FRT | Apr Kmr; mobilizable mini-Tn7 base vector | 7 |

| pUC18T-mini-Tn7T-Zeo-FRT | Apr Zeor; mobilizable mini-Tn7 base vector | 7 |

| pFKM2 | Apr Kmr; source of FRT-nptII-FRT cassette | 7 |

| pFLPe2 | Zeor; curable Flp recombinase expression vector | 7 |

| pFLPe4 | Kmr; curable Flp recombinase expression vector | 7 |

| pFZE1 | Apr Zeor; source of FRT-PEM7-ble-FRT cassette | 7 |

| pPS856 | Apr Gmr; source of FRT-aacC1-FRT cassette | 15 |

| pPS1615 | Cmr; fosmid clone with a 35.5-kb 1026b DNA chromosomal insert containing the bpeR-bpeAB-oprB region | M. Jacobs, University of Washington |

| pPS2009 | Apr; pWSK29 with EcoRI fragment from pPS1615 containing the bpeR-bpeAB-oprB region | This study |

| pPS2254 | Apr Zeor; pGEM-T Easy (Promega, Madison, WI) with Δ(amrRAB-oprA)::FRT-PEM7-ble-FRT allele | This study |

| pPS2296 | Apr Zeor; pGEM-T Easy with ΔbpeR::FRT-PEM7-ble-FRT recombinant DNA fragment | This study |

| pPS2321 | Apr; pGEM-T Easy with bpeR+ | This study |

| pPS2323 | Apr Kmr; pUC18T-mini-Tn7T-Km-FRT with bpeR+ | This study |

| pPS2333 | Apr; pGEM-T Easy with P1-bpeR+ | This study |

| pPS2339 | Apr Zeor; pUC18T-mini-Tn7T-Zeo-FRT with P1-bpeR+ | This study |

| pPS2411 | Apr Gmr; pGEM-T Easy with Δ(bpeAB-oprB)::FRT-aacC1-FRT recombinant DNA fragment | This study |

| pPS2412 | Apr Kmr; pGEM-T Easy with Δ(bpeAB-oprB)::FRT-nptII-FRT recombinant DNA fragment | This study |

| pPS2482 | Apr Zeor; pUC18T-mini-Tn7T-Zeo-FRT with bpeA+B+-oprB+ 5′ region | This study |

| pPS2502 | Apr Zeor; pUC18T-mini-Tn7T-Zeo-FRT with bpeA+B+-oprB+ | This study |

| pPS2551 | Apr; pPS2254 with Δ(amrRAB-oprA) and FRT-PEM7-ble-FRT deleted | This study |

| pPS2557 | Kmr; pEXKm5 with Δ(amrRAB-oprA)-containing fragment from pPS2551 | This study |

Abbreviations: Ap, ampicillin; Cm, chloramphenicol; Gm, gentamicin; Km, kanamycin; Zeo, zeocin. All chromosomal mini-Tn7 insertions used in this study are located at the glmS2-associated attachment site (7). PEM7 is a synthetic prokaryotic promoter.

DNA and genetic methods.

Published procedures were employed for manipulation of DNA and transformation of E. coli (32). DNA fragments were purified from agarose gels by use of a Fermentas DNA extraction kit (Glen Burnie, MD). Colony PCR with B. pseudomallei was performed as previously described (7). Custom oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Isolation of chromosomally integrated mini-Tn7 elements followed by Flp-mediated selection marker excision was performed using previously published procedures (7, 8). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the methods and primer sets described by Kumar et al. (18), with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were grown at 37°C in LB medium to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm, ∼0.7). Total RNA was extracted from 1 ml of culture by using an RNeasy Mini kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). One microgram of RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase I from Fermentas, and cDNA was synthesized using Invitrogen SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix for quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). qRT-PCR was performed with an iQ5 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), using Invitrogen's SYBR GreenER qPCR SuperMix for iCycler. Primers were designed using the OligoPerfect primer design tool from Invitrogen. The primers used were bpeR-RT-F and bpeR-RT-R for bpeR, bpeB-F1-RT and bpeB-R1-RT for bpeB, and Bp23S-F and Bp23S-R for the 23S rRNA housekeeping control (primer sequences are listed in Table 2). Melting curve analysis was performed on all reactions to rule out secondary products and primer dimer formation. Standard curves were constructed using a series of DNA concentrations of extracted chromosomal DNA from a 1026b culture.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)a |

|---|---|

| bpeR-RT-F | GCGAAATCCTGATCTGGTG |

| bpeR-RT-R | TGAACAGGATGCTGAACACG |

| bpeB-F1-RT | GGCCTCGACAACTTCCTGTA |

| bpeB-R1-RT | TTGTTCTGCACCTGAACCTG |

| Bp23S-F | GTAGACCCGAAACCAGGTGA |

| Bp23S-R | CACCCCTATCCACAGCTCAT |

| bpeR-UP-For | CGTCGTACTGCTGCTTGCTG |

| bpeR-UP-Rev-GM | tcagagcgcttttgaagctaattcgCTTCCTCCTTCGTGCGTCTG |

| bpeR-DN-For-GM | aggaacttcaagatccccaattcgGATGCGCAAGGACGACTGAG |

| bpeR-DN-Rev | ACACGAGACGCACGCTGAAC |

| GmFRT-UP | cgaattagcttcaaaagcgctctga |

| GmFRT-DN | cgaattggggatcttgaagtacct |

| bpeR-check-For | CAGACGCACGAAGGAGGAAG |

| bpeR-check-Rev | CTCAGTCGTCCTTGCGCATC |

| bpeA-For | GTACGAGCGCCTATCTGGTC |

| bpeA-Rev-FRT | aggaacttcaagatccccaattcgGCTCTCGACCACCCAGTTCT |

| oprB-For-FRT | tcagagcgcttttgaagctaattcgAGATCGCGCTGAAGAACAAC |

| oprB-Rev | CTCTGGATCGCCTTCTCGTA |

| bpeR-For primer | GGAGGGAAATCAGCAGAGAC |

| bpeR-Rev primer | CGTCACGTGAGTTTCGCGAC |

| bpeR-SOEing-For | ATGGCCAGACGCACGAAGGAG |

| bpeR-SOEing-Rev | CGTCACGTGAGTTTCGCGAC |

| P1-SOEing-For-EcoRV | GGGATATCGAATTCACGAACCCAGTTGAC |

| P1-bpeR-SOEing-Rev | CTCCTTCGTGCGTCTGGCCATGTCGAATCCTTCTTGTGAATC |

Uppercase letters denote chromosome- or plasmid-specific sequences, and lowercase letters denote FRT cassette-specific sequences.

Mutant construction.

Gene disruption by deletion of bpeR and bpeAB-oprB was performed using a previously described DNA fragment transformation method (7, 37). Briefly, using 5 to 50 ng of chromosomal or plasmid DNA templates, three partially overlapping DNA fragments, representing flanking DNA segments and a fragment encoding an antibiotic resistance marker, were PCR amplified separately using Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and then spliced together by overlap extension PCR. For bpeR, the amplified fragments were an 883-bp bpeR upstream fragment, amplified with primers bpeR-UP-For and bpeR-UP-Rev-GM; an 875-bp bpeR downstream fragment, amplified with primers bpeR-DN-For-GM and bpeR-DN-Rev; and a 776-bp zeocin resistance-encoding ble fragment from pFZE1 (7), amplified using GmFRT-UP and GmFRT-DN. These fragments were combined in a second PCR, and after gel purification, the resulting recombinant, 2,485-bp DNA fragment was cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega, Madison, WI), which yielded pPS2296. The plasmid-borne deletion was transferred to the B. pseudomallei Bp50 genome by a previously described DNA fragment transformation method (7, 37). Zeocin-resistant transformants were selected on LB-zeocin plates. Deletion of the bpeR gene was confirmed by colony PCR with primers bpeR-check-For and bpeR-check-Rev, using a previously described procedure (7). Finally, an unmarked ΔbpeR::FRT deletion mutant was obtained by Flp-mediated excision of the zeocin resistance marker, using pFLPe4 (7). The presence of ΔbpeR::FRT was verified by colony PCR using the aforementioned bpeR primers.

The bpeAB-oprB deletion mutants of Bp50 and 1026b, i.e., Bp207 and Bp227, respectively, were isolated using the same methods, except that the following DNA fragments were used (described for Bp207, with deviations for Bp227 isolation indicated in parentheses). A 905-bp bpeA upstream fragment was amplified using primers bpeA-For and bpeA-Rev-FRT, a 956-bp oprB downstream fragment was amplified using oprB-For-FRT and oprB-Rev, and a 1,054-bp aacC1 fragment was amplified from pPS856 (a 1,420-bp nptII fragment was amplified from pFKM2), using GmFRT-UP and GmFRT-DN. These fragments were combined in a second PCR, and after gel purification, the resulting recombinant, 2,866-bp (3,232-bp) DNA fragment was cloned into pGEM-T Easy, which yielded pPS2411 (pPS2412). The plasmid-borne deletion was transferred to the B. pseudomallei Bp50 (1026b) chromosome, gentamicin (kanamycin)-resistant transformants were selected on LB-gentamicin (LB-kanamycin) plates, and the deletion of bpeAB-oprB was confirmed by colony PCR using primers bpeA-For and oprB-Rev. Finally, the unmarked Δ(bpeAB-oprB)::FRT deletion mutant Bp207 (Bp227) was obtained by Flp-mediated excision of the gentamicin (kanamycin) resistance marker, using pFLPe4 (pFLPe2).

For construction of the Δ(amrRAB-oprA) mutant Bp340, containing the same amrRAB-oprA deletion as Bp50, but without the FRT scar, a 1,124-bp XhoI fragment was deleted from pPS2254 to remove the FRT-ble-FRT cassette, creating pPS2551. Next, a 1,329-bp EcoRI fragment of pPS2551 containing Δ(amrRAB-oprA) with flanking sequences was ligated into the EcoRI site of pEXKm5 (22), resulting in pPS2557. This plasmid was electroporated into 1026b, and transformants were selected on LB plates containing 1,000 μg/ml kanamycin and 50 μg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide (X-Gluc; Gold Biotechnology). Kanamycin-resistant, blue merodiploids were resolved by streaking colonies on yeast tryptone (YT) (22) plates containing 15% sucrose and X-Gluc. Colonies growing on these plates were screened for gentamicin sensitivity, and the amrRAB-oprA deletion was confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing. To create the Δ(amrRAB-oprA) Δ(bpeAB-oprB) double mutant Bp400, the Δ(amrRAB-oprA) allele contained on pPS2557 was transferred to the Bp227 chromosome by the method outlined above for construction of Bp340.

Construction of mini-Tn7 elements for bpeR expression and complementation.

Mini-Tn7 constructs were engineered in which bpeR was expressed from either its native promoter or the strong P1 integron promoter (13). To obtain a construct in which bpeR was expressed from its native promoter, a 1,129-bp DNA fragment containing the bpeR gene and its predicted (Neural Network Promoter Prediction [www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html]) promoter was amplified from chromosomal DNA of 1026b, using bpeR-For primer, bpeR-Rev primer, and Hi-Fi Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). The gel-purified PCR product was cloned into pGEM-T Easy, which yielded pPS2321. Finally, a 1,149-bp EcoRI fragment from pPS2321, containing the bpeR gene with the predicted promoter, was ligated into the EcoRI site of pUC18T-mini-Tn7T-Km-FRT, which yielded pPS2323. To obtain a construct in which bpeR was expressed from the P1 promoter, an 892-bp DNA fragment containing the bpeR gene was amplified from chromosomal DNA of 1026b by using primers bpeR-SOEing-For and bpeR-SOEing-Rev and Hi-Fi Taq polymerase. A 399-bp DNA fragment containing the P1 promoter was amplified from the p34E-Tp1 plasmid by using primers P1-SOEing-For-EcoRV and P1-bpeR-SOEing-Rev. These fragments were combined in a second PCR, and after gel purification, the resulting recombinant, 1,270-bp DNA fragment was cloned into pGEM-T Easy, which yielded pPS2333. A 1,266-bp EcoRI fragment containing the P1-bpeR fusion from pPS2333 was then ligated into the EcoRI site of pUC18T-mini-Tn7T-Zeo-FRT, which yielded pPS2339.

Construction of a mini-Tn7 element expressing bpeAB-oprB.

An 11,933-bp EcoRI fragment of pPS1615 containing bpeR-bpeAB-oprB was ligated into the EcoRI site of the low-copy-number plasmid pWSK29 (41), which yielded pPS2009. The bpeAB-oprB region from pPS2009, without bpeR, was then transferred to a mini-Tn7 delivery vector in two steps. First, a 3,916-bp EcoRV-BamHI fragment of pPS2009, containing the 5′ region of bpeAB-oprB with the predicted promoter, was ligated between the NruI and BamHI sites of pUC18T-mini-Tn7T-Zeo-FRT, which yielded pPS2482. Second, a 3,339-bp BamHI fragment of pPS2009, containing the 3′ region of bpeAB-oprB, was ligated into the BamHI site of pPS2482, which yielded pPS2502.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

MICs were determined in Mueller-Hinton broth (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) by the 2-fold broth microdilution technique following Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (9). The MICs were recorded after incubation at 37°C for 24 h.

Bioassays.

To assess AHL production, B. pseudomallei strains were grown in 2 ml LB broth at 37°C for 24 h. Cells were removed from the overnight culture by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge at full speed at room temperature for 1 min. The supernatant was saved and filter sterilized. AHLs were detected using the Agrobacterium tumefaciens NTL4/pZLR4 reporter strain (23). An overnight culture of NTL4/pZLR4 grown at 30°C in LB broth containing 30 μg/ml gentamicin was diluted 100-fold in the same medium. One milliliter of this diluted culture was combined with 1 ml of filter-sterilized B. pseudomallei culture supernatant, and the mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 24 h. β-Galactosidase activities in chloroform-SDS-permeabilized cells were then measured and calculated as previously described (25). All assays were performed in triplicate.

Siderophore production in cell-free supernatants was assessed using a previously described chemical assay (33). B. pseudomallei strains were grown in 2 ml of deferrated CAA medium for 24 h at 37°C, and cell densities were determined by reading the absorbance at 600 nm (A600). Cells were removed from the overnight cultures by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge at full speed (1 min, room temperature). For the assay, 100 μl of culture supernatant was added to 900 μl of chrome azurol S assay solution, and the mixture was incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The absorbance was read at 630 nm (A630). Siderophore activity was expressed as the change in A630 readings (ΔA630) between the test samples and the sample blank (deferrated CAA medium without cells) and was normalized for cell density by being expressed as a ratio of ΔA630 to A600. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Biofilm formation was assayed using the method described by O'Toole and Kolter (29), with minor modifications. Cells from a 2-ml bacterial culture grown in LB medium overnight at 37°C were diluted 1:100 in 2 ml LB medium. Three 100-μl aliquots of the diluted culture were added to three separate wells of a Falcon 96-well flexible polyvinylchloride U-bottomed plate (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Blank wells contained LB medium only. After incubation of the plate for 20 h at 37°C, nonadhering planktonic cells were removed and the wells washed twice with water. Adherent cells were stained with 125 μl of 1% (wt/vol) crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min at room temperature and then washed three times with water. Residual stain was dissolved by sequentially adding two 100-μl aliquots of 95% (vol/vol) ethanol. The resulting 200 μl of dye solution was then transferred to a fresh 96-well plate for measurement of the A595, using a Synergy HT multimode microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT). All assays were performed in triplicate.

To assess swimming motility, 5 μl of overnight culture grown in LB medium at 37°C was spotted onto LB medium containing 0.3% agar. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 20 h before measurement of the diameters of the swimming zones.

RESULTS

Strain 1026b BpeAB-OprB does not mediate efflux of aminoglycosides.

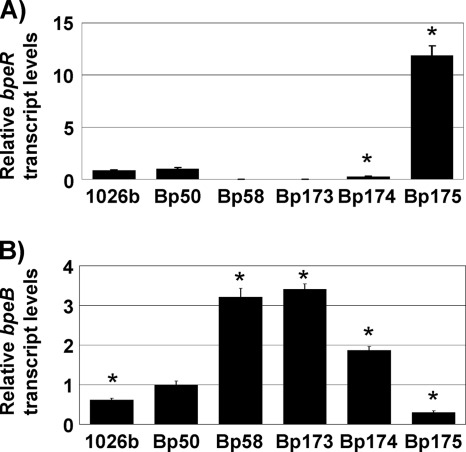

While studying efflux pump gene function in B. pseudomallei, we constructed defined efflux pump deletion strains. In the course of these studies, we noted—in concordance with previous studies (27)—that the 1026b Δ(amrRAB-oprA) mutant Bp50 was highly susceptible to the aminoglycosides gentamicin, kanamycin, spectinomycin, and streptomycin and, to a lesser degree, the macrolides clarithromycin and erythromycin (Table 3), despite the fact that this strain expressed elevated levels of bpeB compared to those in 1026b (Fig. 1 B). In contrast, deletion of bpeAB-oprB from 1026b did not reveal any significant susceptibility differences between the wild type and mutant Bp227 (Table 3). This suggested that in wild-type cells, either BpeAB-OprB does not mediate efflux of aminoglycosides or its expression levels are too low for detection of susceptibility differences. The latter is unlikely, since Bp50 did not show any decreased resistance to antibiotics, for instance, fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines, which are substrates of both AmrAB-OprA and BpeAB-OprB, as shown here for the first time.

TABLE 3.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of B. pseudomallei strainsa

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1026b | Bp50 | Bp227 | Bp58 | Bp173 | Bp174 | Bp175 | Bp207 | Bp216 | Bp250 | |

| Gentamicin | 512 | 2 | 256 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Kanamycin | 64 | 4 | 64 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Spectinomycin | 2,048 | 64 | 1,024 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| Streptomycin | >2,048 | 16 | 2,048 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Clarithromycin | 128 | 8 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Erythromycin | 128 | 8 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Clindamycin | >4,096 | 4,096 | 2,048 | >4,096 | >4,096 | >4,096 | 512 | 128 | 128 | 4,096 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.5 |

| Norfloxacin | 4 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 4 |

| Ofloxacin | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 1 |

| Doxycycline | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.25 |

| Tetracycline | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.13 |

| Chloramphenicol | 8 | 8 | 4 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Carbenicillin | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 |

| Ceftazidime | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Acriflavine | 32 | 16 | 16 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 16 |

The genotypes of the tested strains were as follows: Bp50, 1026b Δ(amrRAB-oprA); Bp58, Bp50 ΔbpeR; Bp173, Bp58 with mini-Tn7T; Bp174, Bp58 with mini-Tn7T expressing bpeR from its own promoter; Bp175, Bp58 with mini-Tn7T expressing bpeR from the P1 promoter; Bp207, Bp50 Δ(bpeAB-oprB); Bp216, Bp207 with mini-Tn7T; Bp227, 1026b Δ(bpeAB-oprB); Bp250, Bp207 with mini-Tn7T expressing 1026b bpeAB-oprB from its own promoter.

FIG. 1.

bpeR and bpeB transcript levels in wild-type, deletion, and complemented strains. mRNA levels in LB-grown mid-log cultures of the indicated strains were determined with bpeR- and bpeB-specific primer sets. Data were normalized using the 23S rRNA gene as the housekeeping control. (A) bpeR transcript levels relative to those found in Bp50 were determined for the following strains: wild-type 1026b, its Δ(amrRAB-oprA) derivative Bp50, and its Δ(amrRAB-oprA) ΔbpeR derivative Bp58. Bp173, Bp174, and Bp175 are Bp58 mutants containing an empty mini-Tn7 vector, a mini-Tn7 element expressing bpeR from its own promoter, and a mini-Tn7 element expressing bpeR from the constitutive P1 promoter, respectively. Asterisks mark bpeR mRNA levels that are statistically significantly different (according to t test) from those detected in 1026b. (B) bpeB transcript levels in the same strains as above relative to the levels found in Bp50. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Error bars represent standard deviations. Asterisks mark bpeB mRNA levels that are statistically significantly different (according to t test) from those detected in Bp50.

Derepression and hyperrepression of BpeAB-OprB confirm negative regulation and reveal new pump substrates.

It was previously shown that bpeAB-oprB expression is repressed by the product of the divergently transcribed bpeR gene (4). To assess the effects of increased BpeAB-OprB expression on antibiotic resistance in the Δ(amrRAB-oprA) background, we mutated bpeR in strain Bp50. As expected, no bpeR mRNA was detectable in the bpeR mutant, Bp58 (Fig. 1A), and bpeB transcripts in the mutant were increased 6- and 3-fold compared to those in strains 1026b and Bp50, respectively (Fig. 1B). MIC determinations revealed that Bp58 did not mediate efflux of any of the aminoglycosides tested, but resistance to macrolides (clarithromycin and erythromycin), fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, and ofloxacin), tetracyclines (doxycycline and tetracycline), and acriflavine was significantly (4-fold) increased, while resistance to chloramphenicol was only marginally (2-fold) increased (Table 3). Compared to those for strain 1026b, the MICs for doxycycline and chloramphenicol were only marginally (2-fold) increased and therefore clinically nonsignificant. Although single-copy complementation with bpeR expressed from its own promoter in Bp174 was incomplete, i.e., it neither raised bpeR mRNA levels to those seen in Bp50 (Fig. 1A) nor resulted in bpeB mRNA levels reduced to those seen in Bp50 (Fig. 1B), susceptibility to all of these antibiotics was markedly decreased (Table 3). Hyperrepression by BpeR overproduced by expression of its structural gene from the strong P1 promoter in Bp175 resulted in high levels of bpeR mRNA (Fig. 1A) and in bpeB mRNA levels lower than those observed in the wild type or Bp50 (Fig. 1B). The severely reduced BpeAB-OprB expression resulted in hypersusceptibility to macrolides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, and acriflavine and susceptibility to clindamycin and chloramphenicol. In contrast, susceptibility to all aminoglycosides remained the same as that observed in Bp50, Bp58, or Bp173, which is Bp58 with an empty mini-Tn7 insertion. These data confirmed the previous observation that BpeAB-OprB mediates efflux of erythromycin and acriflavine and revealed new substrates, namely, other macrolides, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, and tetracyclines.

BpeAB-OprB mutants are hypersusceptible to structurally unrelated drugs.

To test the notion that BpeAB-OprB was responsible for the observed resistance to macrolides, clindamycin, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, and acriflavine, the bpeAB-oprB operon was deleted from Bp50 and the susceptibilities to these drugs for the resulting Δ(amrRAB-oprA) Δ(bpeAB-oprB) strain, Bp207, were assessed. It is evident that this strain is hypersusceptible to macrolides, clindamycin, fluoroquinolones, and tetracyclines and susceptible to chloramphenicol and acriflavine (Table 3). Again, susceptibility to aminoglycosides remained the same as that observed in the parental Δ(amrRAB-oprA) strain, Bp50. Finally, complementation of the Bp207 Δ(bpeAB-oprB) deletion mutant with a chromosomally integrated copy of bpeA+B+-oprB+ expressed from its endogenous promoter restored macrolide, clindamycin, fluoroquinolone, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and acriflavine MICs to levels similar to those observed in Bp50. Complementation did not restore aminoglycoside resistance. MICs for Bp216 containing the vector control were the same as those for Bp207.

BpeAB-OprB mutants are not deficient in acylated homoserine lactone excretion and exhibit normal virulence factor production but are impaired in biofilm formation in an AmrAB-OprA background.

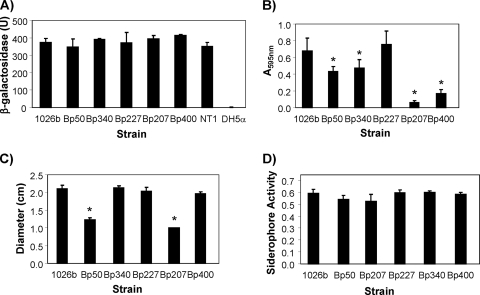

Using strain KHW, it was previously shown that BpeAB-OprB of this strain is required for AHL production and secretion (3, 4). Because AHLs play crucial roles in regulation of virulence factor synthesis, it is perhaps not too surprising that B. pseudomallei KHW BpeAB-OprB mutants showed not only reduced virulence factor production but also reduced cell adherence and penetration, as well as reduced virulence, in the Caenorhabditis elegans infection model (4). We therefore assessed AHL secretion and production of selected virulence factors in our B. pseudomallei strain 1026b-derived mutants. All strains tested, including the Δ(bpeAB-oprB) single and Δ(amrRAB-oprA) Δ(bpeAB-oprB) double mutants, secreted similar amounts of AHLs (Fig. 2 A). All strains tested also produced normal levels of siderophores (Fig. 2D). The Δ(amrRAB-oprA) strain Bp50 and its Δ(bpeAB-oprB) derivative Bp207 showed a statistically significant reduction in swimming motility compared to 1026b (Fig. 2C), as well as a biofilm defect (Fig. 2B). We thought that this was probably due to a mysterious growth defect of Bp50 and its Bp207 derivative. (Bp50 and Bp207 grow slightly slower in rich media and markedly slower in minimal media than the parental strain 1026b and other 1026b-derived mutants.) To test this notion, we tested two other Δ(amrRAB-oprA) derivatives of 1026b, Bp340 and Bp400, which did not exhibit the mysterious growth defect. These analyses revealed that AmrAB-OprA and BpeAB-OprB were not required for normal swimming motility (Fig. 2C), but while the biofilm formation defects were less severe than those observed with Bp50 and Bp207, the mutants lacking either only AmrAB-OprA (Bp340) or both AmrAB-OprA and BpeAB-OprB (Bp400) still formed significantly less biofilm than did 1026b (Fig. 2B). This was consistent with both efflux pumps being important for normal biofilm formation. Curiously, however, biofilm formation was not impaired in Bp227, missing only BpeAB-OprB. It should be noted that the growth defect of Bp50 and its derivatives had no effect on antibiotic resistance, since susceptibility profiles of Bp50 and Bp340, as well as those of Bp207 and Bp400, were identical (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Production of acylated homoserine lactones and selected virulence factors in B. pseudomallei efflux mutants. The following strains were analyzed: 1026b, wild type; Bp50 and Bp340, Δ(amrRAB-oprA) derivatives of 1026b; Bp207 and Bp400, Δ(amrRAB-oprA) Δ(bpeAB-oprB) derivatives of 1026b; and Bp227, a Δ(bpeAB-oprB) derivative of 1026b. For AHL production assays, the positive control was A. tumefaciens strain NT1/pTiC58 ΔaccR and the negative control was E. coli DH5α. (A) AHL production was measured as AHL-stimulated β-galactosidase activity, using the A. tumefaciens indicator strain NT4/pZLR4, as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Biofilm formation was assayed using adhesion to polystyrene, followed by crystal violet staining and measuring the amount of solubilized dye at 595 nm. (C) Swimming motility was assessed by inoculation of LB-0.3% agar plates, followed by measurement of diameters of the resulting migration zones. (D) Total siderophore activity was measured using a universal chrome azurol S siderophore assay. Data shown are from experiments performed in triplicate and on three separate occasions. Errors bars represent standard deviations. Asterisks indicate levels of biofilm formation and swimming motility that are statistically significantly different (according to t test) from those detected in 1026b.

DISCUSSION

Among the RND efflux pumps encoded by B. pseudomallei (at least 10), AmrAB-OprA of strain 1026b (27) and BpeAB-OprB of strain KHW (5) are the only systems that have previously been characterized in some detail. According to previous studies, these efflux pumps share some substrates, most notably aminoglycosides and macrolides. In concordance with previous studies (27), we noticed that AmrAB-OprA-deficient mutants of 1026b are aminoglycoside susceptible, despite the fact that they contain BpeAB-OprB. To assess this apparent discrepancy, we set out to use a set of defined mutant strains of 1026b to study the expression of AmrAB-OprA and BpeAB-OprB and their relative contributions to resistance to diverse antimicrobials. Our data show the following. (i) BpeAB-OprB is expressed at significant levels in wild-type B. pseudomallei 1026b. (ii) BpeAB-OprB shares substrates with AmrAB-OprA, e.g., acriflavine, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and tetracyclines, some of which had previously not been associated with these pumps. Both efflux pumps thus contribute to intrinsic resistance to these antibiotics. (iii) BpeAB-OprB expression is derepressed in a bpeR mutant and hyperrepressed in a BpeR-overproducing strain. (iv) As previously shown for strain KHW, BpeAB-OprB of 1026b extrudes erythromycin and acriflavine. However, in contrast to what was previously described for KHW, strain 1026b BpeAB-OprB does not mediate efflux of aminoglycosides. Use of defined mutants and MIC determinations in a Δ(amrRAB-oprA) background identified chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, and tetracyclines as additional BpeAB-OprB substrates. This is the first report of B. pseudomallei resistance mechanisms for these three classes of antibiotics. Doxycycline is a clinically significant antibiotic, but the level of resistance caused by BpeAB-OprB is probably not clinically significant, since strains expressing this pump still respond to treatment.

At present, we do not know why our BpeAB-OprB susceptibility results with 1026b and its derivatives are different from those previously obtained with and published for Singapore strain KHW. Sequence alignments of KHW BpeA, BpeB, and OprB amino acid sequences with the corresponding sequences from six other B. pseudomallei strains revealed 100% identity of KHW BpeB to those from 1026b and four other strains (with a single K956N change in strain K96243). For the first 396 amino acids, KHW BpeA is 100% identical to 1026b BpeA. Curiously, the sequence of KHW BpeA then diverges completely from those of the BpeA proteins of the six other strains, which are identical and of the same length (420 amino acids versus 429 amino acids in KHW). With the exception of histidine 451, which is a glutamine in the OprB proteins of the six other strains, the 472 amino acids of KHW OprB are identical to those in five of the six other strains. However, all other OprB proteins are 514 amino acids long, with identical carboxy termini. While in the absence of further experimentation we cannot rule out that the KHW BpeA and OprB changes could be the cause of an altered substrate profile, this seems unlikely, as substrate binding and specificity are mediated and determined by the RND transporter component rather than the membrane fusion or outer membrane channel proteins (44, 45). Our findings are not strain specific, as we recently showed that lack of expression or deletion of AmrAB-OprA in three different Thai isolates is the molecular basis for the observed aminoglycoside susceptibility of these strains (38), despite the fact that BLAST searches of the genome sequence of one of these strains (www.mggen.nau.edu/MGGen_research.html) revealed the presence of the bpeAB-oprB genes. However, at present, we do not know whether BpeAB-OprB is functional in this strain. Complementation with an amrA+B+-oprA+ operon from 1026b restored high-level aminoglycoside resistance to all amrAB-oprA mutant strains studied to date. Furthermore, studies with AmrAB-OprA and BpeAB-OprB from the closely related species Burkholderia thailandensis also showed that AmrAB-OprA, but not BpeAB-OprB, is responsible for high-level aminoglycoside resistance of wild-type B. thailandensis (2, 39; L. A. Trunck and H. P. Schweizer, unpublished observations). Lastly, while it contains BpeAB-OprB (BMA_0315-BMA_0316-BMA_0317), the closely related Burkholderia mallei strain ATCC 23344 lacks the AmrAB-OprA system, which likely contributes to its aminoglycoside susceptibility (28, 36).

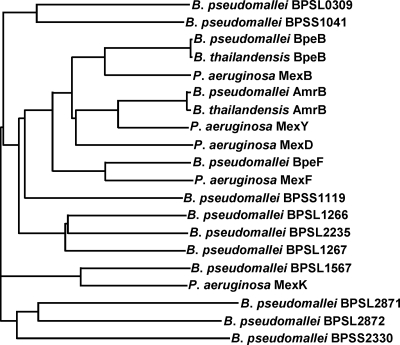

Aminoglycosides are generally not good substrates for RND efflux pumps. For example, in P. aeruginosa only one of 12 RND pumps, MexXY-OprM, extrudes aminoglycosides (24, 26). Phylogenetic analyses using the BpeB sequence as a query revealed that this transporter is most closely related to P. aeruginosa MexB (Fig. 3). MexB is the membrane transporter of the MexAB-OprM system, which does not mediate efflux of aminoglycosides but has a substrate spectrum that closely matches that of BpeAB-OprB (20, 24, 31), with the exception of certain β-lactam antibiotics, e.g., carbenicillin, which are substrates of MexAB-OprM but not BpeAB-OprB. Conversely, AmrB is most closely related to P. aeruginosa MexY, and both the AmrAB-OprA and MexXY-OprM pumps mediate efflux of aminoglycosides. These analyses are in complete agreement with our substrate specificity studies. Two Burkholderia cenocepacia efflux pumps, BCAS0591-BCAS0592-BCAS0593 and BCAL2822-BCAL2821-BCAL2820, are related to BpeAB-OprB, and preliminary data suggested that they may play a role in aminoglycoside resistance (1, 14). Deletion of the BCAL2822-BCAL2821-BCAL2820 genes from a wild-type strain resulted in 2- and 4-fold reductions of gentamicin and tobramycin resistance, respectively (1). Overexpression of the BCAS0591-BCAS0592-BCAS0593 genes from a plasmid and a strong promoter in E. coli resulted in a 16-fold increase in resistance to streptomycin (14). Interestingly, deletion of the BCAL1674-BCAL1675-BCAL1676 pump, which is most closely related to AmrAB-OprA, from wild-type B. cenocepacia had no effect on gentamicin and tobramycin susceptibilities (1).

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic relationships of RND transporters from B. thailandensis E264, B. pseudomallei K96243, and P. aeruginosa PAO1. Phylogenetic relationships were determined using ClustalW (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw/).

As mentioned above, BpeAB-OprB was not only implicated in B. pseudomallei KHW multidrug resistance but also played a crucial role in AHL production and export, most notably in those of octanoyl-homoserine lactone (C8-HSL) (3, 4). This is a crucial finding, because AHLs play pivotal roles in regulation of diverse virulence factors and other physiological processes. We therefore assessed expression and/or production of some of the factors previously shown to be dependent on the presence of a functional BpeAB-OprB system. These included AHL production, biofilm formation, siderophore production, and swimming motility. With the exception of biofilm formation, which was significantly more impaired in the AmrAB-OprA BpeAB-OprB double mutants than in any of the other strains, indicating a possible contributing role of BpeAB-OprB in the Δ(amrAB-oprA) mutant background but not in the wild-type background, none of the other factors tested were dependent on the presence of a functional BpeAB-OprB system. Again, we presently do not know why our BpeAB-OprB virulence factor production results with 1026b and its derivatives are different from those previously obtained with and published for Singapore strain KHW.

Unfortunately, at the time of these studies, strain KHW was not available for comparisons. Our findings illustrate the importance of availability of strains for comparative studies, which is especially paramount for a genetically diverse species such as B. pseudomallei.

Acknowledgments

H.P.S. was supported by NIH NIAID grant U54 AI065357.

We thank Heather Blair for constructing pPS2009; M. Jacobs, University of Washington, for providing a fosmid clone containing the B. pseudomallei 1026b bpeAB-oprB region; and Patrick Tan and Tannistha Nandi from the Genome Institute of Singapore for sharing unpublished KHW sequence data.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 May 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buroni, S., M. R. Pasca, R. S. Flannagan, S. Bazzini, A. Milano, I. Bertani, V. Venturi, M. A. Valvano, and G. Riccardi. 2009. Assessment of three resistance-nodulation-cell division drug efflux transporters of Burkholderia cenocepacia in intrinsic antibiotic resistance. BMC Microbiol. 9:200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burtnick, M. N., A. J. Bolton, P. J. Brett, D. Watanabe, and D. E. Woods. 2001. Identification of the acid phosphatase (acpA) gene homologues in pathogenic and non-pathogenic Burkholderia spp. facilitates TnphoA mutagenesis. Microbiology 147:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan, Y. Y., H. S. Bian, T. M. Tan, M. E. Mattmann, G. D. Geske, J. Igarashi, T. Hatano, H. Suga, H. E. Blackwell, and K. L. Chua. 2007. Control of quorum sensing by a Burkholderia pseudomallei multidrug efflux pump. J. Bacteriol. 189:4320-4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan, Y. Y., and K. L. Chua. 2005. The Burkholderia pseudomallei BpeAB-OprB efflux pump: expression and impact on quorum sensing and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 187:4707-4719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan, Y. Y., T. M. C. Tan, Y. M. Ong, and K. L. Chua. 2004. BpeAB-OprB, a multidrug efflux pump in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1128-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng, A. C., and B. J. Currie. 2005. Melioidosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:383-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi, K.-H., T. Mima, Y. Casart, D. Rholl, A. Kumar, I. R. Beacham, and H. P. Schweizer. 2008. Genetic tools for select agent compliant manipulation of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:1064-1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi, K. H., J. B. Gaynor, K. G. White, C. Lopez, C. M. Bosio, R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, and H. P. Schweizer. 2005. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat. Methods 2:443-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2006. M7-A7. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, 7th ed. CLSI, Wayne, PA.

- 10.Currie, B. J., D. A. B. Dance, and A. C. Cheng. 2008. The global distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and melioidosis: an update. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102(Suppl. 1):S1-S4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damier-Piolle, L., S. Magnet, S. Bremont, T. Lambert, and P. Courvalin. 2008. AdeIJK, a resistance-nodulation-cell division pump effluxing multiple antibiotics in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:557-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeShazer, D., P. Brett, R. Carlyon, and D. Woods. 1997. Mutagenesis of Burkholderia pseudomallei with Tn5-OT182: isolation of motility mutants and molecular characterization of the flagellin structural gene. J. Bacteriol. 179:2116-2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deshazer, D., and D. E. Woods. 1996. Broad-host-range cloning and cassette vectors based on the R388 trimethoprim resistance gene. Biotechniques 20:762-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guglierame, P., M. R. Pasca, E. De Rossi, S. Buroni, P. Arrigo, G. Manina, and G. Riccardi. 2006. Efflux pump genes of the resistance-nodulation-division family in Burkholderia cenocepacia genome. BMC Microbiol. 6:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoang, T. T., R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, A. J. Kutchma, and H. P. Schweizer. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holden, M. T. G., R. W. Titball, S. J. Peacock, A. M. Cerdeno-Tarraga, T. P. Atkins, L. C. Crossman, T. L. Pitt, C. Churcher, K. L. Mungall, S. D. Bentley, M. Sebaihia, N. R. Thomson, N. Bason, I. R. Beacham, K. Brooks, K. A. Brown, N. F. Brown, G. L. Challis, I. Cherevach, T. Chillingworth, A. Cronin, B. Crossett, P. Davis, D. DeShazer, T. Feltwell, A. Fraser, Z. Hance, H. Hauser, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, K. E. Keith, M. Maddison, S. Moule, C. Price, M. A. Quail, E. Rabbinowitsch, K. Rutherford, M. Sanders, M. Simmonds, S. Songsivilai, K. Stevens, S. Tumapa, M. Vesaratchavest, S. Whitehead, C. Yeats, B. G. Barrell, P. C. F. Oyston, and J. Parkhill. 2004. Genomic plasticity of the causative agent of melioidosis, Burkholderia pseudomallei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:14240-14245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar, A., K.-L. Chua, and H. P. Schweizer. 2006. Method for regulated expression of single-copy efflux pump genes in a surrogate Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain: identification of the BpeEF-OprC chloramphenicol and trimethoprim efflux pump of Burkholderia pseudomallei 1026b. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3460-3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar, A., M. Mayo, L. A. Trunck, A. C. Cheng, B. J. Currie, and H. P. Schweizer. 2008. Expression of resistance-nodulation-cell division efflux pumps in commonly used Burkholderia pseudomallei strains and clinical isolates from Northern Australia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102(Suppl. 1):S145-S151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar, A., and H. P. Schweizer. 2005. Bacterial resistance to antibiotics: active efflux and reduced uptake. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 57:1486-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, X. Z., H. Nikaido, and K. Poole. 1995. Role of mexA-mexB-oprM in antibiotic efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1948-1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liss, L. 1987. New M13 host: DH5αF′ competent cells. Focus 9:13. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez, C. M., D. A. Rholl, L. A. Trunck, and H. P. Schweizer. 2009. Versatile dual-technology system for markerless allele replacement in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:6496-6503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo, Z. Q., S. Su, and S. K. Farrand. 2003. In situ activation of the quorum-sensing transcription factor TraR by cognate and noncognate acyl-homoserine lactone ligands: kinetics and consequences. J. Bacteriol. 185:5665-5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masuda, N., E. Sakagawa, S. Ohya, N. Gotoh, H. Tsujimoto, and T. Nishino. 2000. Substrate specificities of MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ and MexXY-OprM efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3322-3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 26.Mine, T., Y. Morita, A. Kataoka, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 1999. Expression in Escherichia coli of a new multidrug efflux pump, MexXY, from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:415-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore, R. A., D. DeShazer, S. Reckseidler, A. Weissman, and D. E. Woods. 1999. Efflux-mediated aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:465-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nierman, W. C., D. DeShazer, H. S. Kim, H. Tettelin, K. E. Nelson, T. Feldblyum, R. L. Ulrich, C. M. Ronning, L. M. Brinkac, S. C. Daugherty, T. D. Davidsen, R. T. Deboy, G. Dimitrov, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. L. Gwinn, D. H. Haft, H. Khouri, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, Y. Mohammoud, W. C. Nelson, D. Radune, C. M. Romero, S. Sarria, J. Selengut, C. Shamblin, S. A. Sullivan, O. White, Y. Yu, N. Zafar, L. Zhou, and C. M. Fraser. 2004. Structural flexibility in the Burkholderia mallei genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:14246-14251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Toole, G. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 28:449-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poole, K. 2005. Efflux-mediated antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:20-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poole, K., K. Krebes, C. McNally, and S. Neshat. 1993. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: evidence for involvement of an efflux operon. J. Bacteriol. 175:7363-7372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 33.Schwyn, B., and J. B. Neilands. 1987. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 160:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sezonov, G., D. Joseleau-Petit, and R. D'Ari. 2007. Escherichia coli physiology in Luria-Bertani broth. J. Bacteriol. 189:8746-8749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sokol, P. A. 1986. Production and utilization of pyochelin by clinical isolates of Pseudomonas cepacia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 23:560-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thibault, F. M., E. Hernandez, D. R. Vidal, M. Girardet, and J. D. Cavallo. 2004. Antibiotic susceptibility of 65 isolates of Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei to 35 antimicrobial agents. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:1134-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thongdee, M., L. A. Gallagher, M. Schell, T. Dharakul, S. Songsivilai, and C. Manoil. 2008. Targeted mutagenesis of Burkholderia thailandensis and Burkholderia pseudomallei through natural transformation of PCR fragments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2985-2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trunck, L. A., K. L. Propst, V. Wuthiekanun, A. Tuanyok, S. M. Beckstrom-Sternberg, J. S. Beckstrom-Sternberg, S. J. Peacock, P. Keim, S. W. Dow, and H. P. Schweizer. 2009. Molecular basis of rare aminoglycoside susceptibility and pathogenesis of Burkholderia pseudomallei clinical isolates from Thailand. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 3:e0000519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ulrich, R. L., H. B. Hines, N. Parthasarathy, and J. A. Jeddeloh. 2004. Mutational analysis and biochemical characterization of the Burkholderia thailandensis DW503 quorum-sensing network. J. Bacteriol. 186:4350-4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vila, J., S. Marti, and J. Sanchez-Cespedes. 2007. Porins, efflux pumps and multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59:1210-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, R. F., and S. R. Kushner. 1991. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene 100:195-199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiersinga, W. J., T. van der Poll, N. J. White, N. P. Day, and S. J. Peacock. 2006. Melioidosis: insights into the pathogenicity of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:272-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wuthiekanun, V., and S. J. Peacock. 2006. Management of melioidosis. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 4:445-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu, E. W., J. R. Aires, and H. Nikaido. 2003. AcrB multidrug efflux pump of Escherichia coli: composite substrate-binding cavity of exceptional flexibility generates its extremely wide substrate specificity. J. Bacteriol. 185:5657-5664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu, E. W., G. McDermott, H. I. Zgurskaya, H. Nikaido, and D. E. Koshland, Jr. 2003. Structural basis of multiple drug-binding capacity of the AcrB multidrug efflux pump. Science 300:976-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang, L., X.-Z. Li, and K. Poole. 2000. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: involvement of a multidrug efflux system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:287-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang, L., X.-Z. Li, and K. Poole. 2001. SmeDEF multidrug efflux pump contributes to intrinsic multidrug resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3497-3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]