Abstract

Previously, an unexplained subcellular localization was reported for a functional fluorescent protein fusion to the response regulator OmpR in Escherichia coli. The pronounced regions of increased fluorescence, or foci, are dependent on OmpR phosphorylation and do not occupy fixed, easily identifiable positions, such as the poles or mid-cell. Here we show that the foci are due to OmpR-YFP (yellow fluorescent protein) fusion binding to specific sites in the chromosome. To identify positions of foci and quantify their fluorescence intensity, we used a simple system to tag virtually any chromosomal location with arrays of lacO or tetO. The brightest foci colocalize with the OmpR-regulated gene ompF, which is strongly expressed under our growth conditions. When we increased OmpR-YFP phosphorylation by stimulating the EnvZ/OmpR system with procaine, we observed a small increase in OmpR-YFP fluorescence at ompF and a significant increase at the OmpR-regulated gene ompC. This supports a model of hierarchical binding of OmpR to the ompF and ompC promoters. Our results explain the inhomogeneous distribution of OmpR-YFP fluorescence in cells and further demonstrate that for a transcription factor expressed at wild-type levels, binding to native sites in the chromosome can be imaged and quantified by fluorescence microscopy.

Several fluorescence microscopy studies of transcription factors in bacteria have revealed tantalizing evidence of subcellular localization of these proteins (1, 3, 11, 16, 26, 31). However, in most cases the biological significance and underlying mechanism of localization are not well understood. At least part of the difficulty in interpreting the distribution of intracellular fluorescence is due to the lack of readily available landmarks within the bacterial cytoplasm. Here we extend standard tools for tagging the Escherichia coli chromosome to demonstrate that fluorescent foci formed by a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) fusion to the transcription factor OmpR colocalize with specific genes. We also show that these foci are likely due to occupation of OmpR binding sites on the DNA and therefore provide a means for studying OmpR binding to native sites in vivo.

The response regulator OmpR and its partner, histidine kinase EnvZ, are a particularly well-characterized two-component system. The signals that directly stimulate EnvZ have not been established; however, changes in extracellular osmolarity by inner membrane impermeable osmolytes, treatment with some lipophilic compounds such as procaine, and expression of small membrane protein MzrA can activate the EnvZ/OmpR system (7, 10, 23, 27, 28, 30). The best-studied OmpR-regulated genes in E. coli are ompF and ompC, which encode the classical porins (7, 27). At high levels of OmpR phosphorylation (OmpR-P), ompF transcription is repressed and ompC transcription is activated. The expression of these genes has been used to infer changes in OmpR phosphorylation and to study EnvZ/OmpR signaling under various physiological conditions.

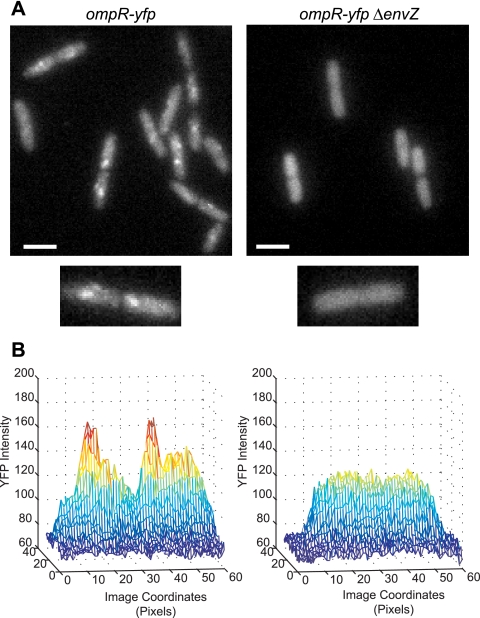

Previously, a subcellular localization was reported for a functional fluorescent protein fusion of YFP or green fluorescent protein (GFP) to OmpR in E. coli (3). In cells expressing OmpR-YFP at roughly wild-type levels, most of the fluorescence appears uniformly distributed throughout the cytoplasm. However, on top of this diffuse background, distinct foci of fluorescence are clearly visible (3) (Fig. 1). Under conditions associated with increased OmpR phosphorylation, the intensity and number of foci increase. Furthermore, they disappear completely under conditions of low OmpR-P (e.g., in envZ deletion strains) (Fig. 1) (3). These foci do not appear at fixed, easily identifiable cellular positions, such as the poles or mid-cell, and they can be eliminated by overexpression of unlabeled OmpR (3). Taken together, prior work suggested that the foci are due to a phosphorylation-dependent increased local concentration or clustering of OmpR-YFP. However, the significance and origin of these foci were not understood.

FIG. 1.

Fluorescence micrographs of live cells displaying OmpR-P-dependent foci of OmpR-YFP fluorescence. (A, left panel) EAL97 (ompR-yfp+). (A, right panel) EPB238 (ompR-yfp+ ΔenvZ). Scale bars represent 2 μm. Cells were grown in minimal glucose medium. (B) Three-dimensional representations of the intensity distributions for the single cells shown in panel A, displayed as a function of image coordinates. For comparison purposes, the images were normalized to have the same average cellular fluorescence.

In this work, we tested the hypothesis that the foci are due to OmpR-YFP binding to the chromosome. The ompF and ompC regulatory regions contain four and three OmpR binding sites, respectively; each site is bound by an OmpR dimer (13, 15, 17, 20, 29). We hypothesized that binding of multiple OmpR-YFP molecules at these sites could produce observable foci. To test this, we marked specific sites in the E. coli chromosome with lac and tet operators, using a simple system for integrating these markers. We show that fluorescent foci are indeed observable at ompF and ompC and are dependent on the presence of OmpR binding sites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

E. coli strains were grown at 37°C, except when propagating plasmids with temperature-sensitive origins of replication (pEL8 and pCP20), which was carried out at 30°C. Plasmids containing the oriR6Kγ origin of replication were propagated in the pir+ E. coli strain PIR2 (Invitrogen). The plasmids and strains used in this work are listed in Table 1 .

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| MG1655 | E. coli Genetic Stock Center, CGSC no. 7740 | |

| BW25113 | 6 | |

| EPB238 | MG1655 Ψ(ompR+-yfp+) ΔenvZ Δ(lacI-lacA)::FRT | 3 |

| EPB273a | MG1655 Ψ(ompR+-yfp+) envZ::kan attλ::(envZ+cat) Φ(ompC+-cfp+) Φ(ompF+-yfp+) | E. Batchelor and M. Goulian, unpublished |

| EPB240 | MG1655 Ψ(ompR+-yfp+) ΔenvZ Δ(lacI-lacA)::FRT attλ::(envZ+cat) | 3 |

| EAL62 | EPB240 ΔompC::(lacO)n | This study |

| EAL70 | EPB240 ΔompF::(lacO)n | This study |

| EAL73 | EPB240 Δ(lacI-lacA)::(lacO)n | This study |

| EAL97 | EPB240 attλ::(envZ+ Δcat::FRT) | This study |

| EAL105 | EAL97 ΔompF::(tetO)n ΔompC::(lacO)n | This study |

| EAL111 | EAL97 Δ[(F1-F4)-ompF]::(tetO)n ΔompC::(lacO)n | This study |

| EAL112 | EAL97 Δ[(F1-F4)-ompF]::(tetO)n Δ[(C1-C3)-ompC]::(lacO)n | This study |

| EAL113 | EAL97 ΔompF::(tetO)n Δ[(C1-C3)-ompC]::(lacO)n | This study |

| EAL81 | BW25113 Δ([(C1-C3)-ompC]::(FRT-kan-FRT) | This study |

| EAL85 | BW25113 ΔompF::(tetO)n Δ(lacI-lacA)::(lacO)n | This study |

| EAL96 | BW25113 Δ[(F1-F4)-ompF]::(FRT-kan-FRT) | This study |

| JW0912 | BW25113 ΔompF::(FRT-kan-FRT) | 2 |

| JW2203 | BW25113 ΔompC::(FRT-kan-FRT) | 2 |

| PIR2 | F− Δlac169 rpoS(Am) robA1 creC510 hsdR514 endA recA1 uidA(ΔMluI)::pir | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| p306tetO224 | (tetO2)n | K. Nasmyth via J. Dworkin |

| pAS02 | pCAH63 Δ(Psyn1-uidAf) tetR+ Φ(tetA+-MCS)a | 3 |

| pCAH63 | oriR6Kγ cat attPλPsyn1-uidAf | 12 |

| pCE40 | oriR6Kγ kan-FRT lacZ+lacY+ | 9 |

| pCP20 | λpR-FLP λcI857+ori(Ts) bla cat | 5 |

| pEB55 | pCAH63 Δ(Psyn1-uidAf) ompR101envZ+ | 3 |

| pEB96 | pBAD18 Para-Ψ(cfp+-lacI+) | 3 |

| pEB127 | Contains (lacO)256 isolated from pSV2-DHFR-8.32b | E. Batchelor and M. Goulian, unpublished |

| pEL5 | oriR6Kγ [tetO2]n FRT cat | This study |

| pEL7 | pBAD18 Para-[Ψ(cfp+-lacI+) Ψ(tetR+-mcherry+)] | This study |

| pEL8 | pCP20 Δcat | This study |

| pEL9 | pCAH63 Δ(Psyn1-uidAf) ompR101 envZ+ Δcat::(FRT-kan-FRT) | This study |

| pRSETb-mcherry | mcherry+ | R. Tsien |

| pSE1 | oriR6Kγ kan-FRT (lacO)256 | This study |

MCS, multiple-cloning site.

For details, see reference 24.

Construction of the CFP-LacI and TetR-mCherry expression plasmid pEL7.

The Tn10 tetR gene was amplified from plasmid pAS02 (3) using the primers 5′-CGAGCCGTCGACAGGAAACAGACCATGTCTAGATTAGATAAAAG-3′ and 5′-CAGTTAGGTACCAGACCCACTTTCACATTTAAG-3′ and digested with SalI and KpnI. The mCherry gene was amplified from pRSETb-mcherry using primers 5′-GAATTAGGTACCGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGG-3′ and 5′-GGCCTCAAGCTTTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATG-3′ and digested with KpnI and HindIII. The above two fragments were ligated to SalI- and HindIII-digested pEB96 (3). The resulting plasmid, pEL7, expresses cfp-lacI and tetR-mcherry translational fusions under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter.

Construction of the tetO array insertion plasmid pEL5.

An array of tetO2 operators was isolated from p306tetO224 by digesting the plasmid with SacI and KpnI. This was ligated to a fragment of pCAH63 (12) (containing cat and oriR6Kγ) that was amplified using the primers 5′-GCATTAGAGCTCGAAGTTCCTATTCTCTAGAAAGAATAGGAACTTCGCAGCAGGGAGGCAAACAATG-3′ (the FLP recombination target [FRT] site is underlined) (9) and 5′-TGTTCGAGCACGAAGCAGACC-3′ and digested with SacI and KpnI. A clone with approximately 100 copies (∼4 kb) of tetO2 repeats was designated pEL5.

Construction of the lacO array insertion plasmid pSE1.

A fragment containing approximately 10 kb of lacO repeats was cut from pEB127 (E. Batchelor and M. Goulian, unpublished data) by digestion with SalI and BamHI and ligated to a fragment of pCE40 (9) (containing FRT, kan, and oriR6Kγ) that was amplified using the primers 5′-CAGGATCCCGTCGTCAGGTGAATG-3′ and 5′-GAGTCGACGGCGATTAAGTTGGGTAACG-3′. A clone with a size consistent with approximately 10 kb of lacO repeats was designated pSE1.

Construction of pEL8, a Δcat derivative of pCP20.

The cat gene in pCP20 (5) was deleted by digestion with SmaI and NcoI, treatment with T4 DNA polymerase to blunt the ends, and ligation of the DNA. The resulting plasmid, pEL8, no longer confers chloramphenicol resistance but is otherwise isogenic with pCP20.

Chromosomal integration of pEL5 and pSE1.

Plasmids were integrated into chromosomal FRT using a protocol similar to that described in reference 9. To integrate pEL5, a strain containing a chromosomal FRT site and plasmid pEL8 was transformed with pEL5 by electroporation and grown on LB plates containing 15 μg/ml chloramphenicol at 37°C. Selected colonies were streaked on LB-chloramphenicol and grown at 37°C. Colonies were then restreaked on LB without antibiotic and grown at 37°C and in parallel streaked on LB with 50 μg/ml ampicillin and grown at 30°C to test for loss of pEL8. The plasmid pSE1 was integrated by essentially the same procedure, except in some cases pCP20 was used for expression of FLP recombinase instead of pEL8, and selective plates consisted of LB agar with 20 μg/ml kanamycin. Insertions in ompF and ompC were constructed in the Keio Collection strains JW0912 and JW2203 (2) or, for the case of OmpR binding site deletions, in the strains EAL81 and EAL96. The insertions in lac were constructed in strain EPB238 (3). Integrated plasmids were moved by P1 transduction, using 35 μg/ml kanamycin or 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol for selection.

Deletion of OmpR binding sites at ompF and ompC.

A deletion of ompC and the three upstream OmpR binding sites was constructed by lambda Red-mediated recombination as in reference 6. The primers 5′-GTGCTGTCAAATACTTAAGAATAAGTTATTGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC-3′ and 5′-CGCAGGCCCTTTGTTCGATATCAATCGAGAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′ were used to amplify the FRT-kan-FRT cassette from pKD13. The underlined sequences in the primers denote sequence upstream of the OmpR binding sites and downstream of the ompC gene, respectively. The PCR product was transformed by electroporation into BW25113/pKD46 as in reference 6, and the deletion was verified by PCR, resulting in strain EAL81.

To delete ompF and the four upstream OmpR binding sites, the same procedure was used as outlined above, but with the primers 5′-TCAAGCAATCTATTTGCAACCCCGCCATAAATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC-3′ and 5′-GAACTGGTAAACGATACCCACAGCAACGGTGGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′, which removes the OmpR binding sites F1 to F4, through to the last 7 amino acids of ompF. The underlined sequences in the primers denote sequences upstream of the OmpR binding sites and the end of ompF, respectively. This strain was named EAL96.

Construction of EAL97.

EPB240 contains the chloramphenicol-resistant plasmid pEB55 integrated at the lambda phage attachment site. The cat antibiotic resistance gene in this integrated plasmid was deleted by lambda Red-mediated recombination with an FRT-kan-FRT cassette, which was amplified from pKD4 (6) using the primers 5′-ATATCCCAATGGCATCGTAAAGAACATTTTGAGGCATTTCAGTCAGTTGCGCTGGAGCTGCTTCGAA-3′ and 5′-ATGAACCTGAATCGCCAGCGGCATCAGCACCTTGTCGCCTTGCGTATAATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG-3′. The underlined sequences in the primers denote sequences in the cat gene. The resulting integrated plasmid (which now confers kanamycin resistance) was moved into a clean EPB240 background by P1 transduction. The kan cassette was then removed using pEL8, resulting in EAL97.

Microscopy.

Cultures were grown overnight to saturation in minimal A medium (19) containing 0.2% glucose and 50 μg/ml ampicillin for plasmid maintenance, when necessary. Cultures were then diluted at least 1:1,000 into the same medium. Where indicated, procaine was added when the optical density at 600 nm reached approximately 0.1. To induce production of LacI-CFP and TetR-mCherry, arabinose was added to 10 mM.

Microscopy was performed on live cells at 37°C essentially as described in reference 3, except that the objective lens was Olympus UPLFLN 100XO2PH (100×, numerical aperture of 1.3, with a phase ring). In addition, a cube containing a Chroma HQ575/50X excitation filter, HQ640/50 M dichroic, and Q610 LP emission filter was used for mCherry fluorescence imaging. A phase-contrast image was first acquired, followed by a 750-ms YFP image, followed by a 400-ms CFP image, and finally a 400-ms mCherry image as indicated.

Image analysis.

Image analysis was based on methods previously outlined in reference 3, with the exception that phase-contrast images were used to identify cell boundaries. To find the brightest OmpR-YFP focus in a cell, the software identified the brightest pixel in the YFP image, subject to the restriction that the pixel value must be at least 2 standard deviations above the average cellular fluorescence and also above a preset value of 55. These restrictions were chosen to minimize false positives. The location of the OmpR-YFP focus was determined by computing the center of mass of a 5-by-5 array of pixels centered on this maximum. To identify the positions of (at most) four CFP-LacI foci, pixel values were required to be above 100 and restricted to at least 1.8 standard deviations above the mean. The CFP maxima were required to be separated by at least 3.5 pixels to be scored as separate foci. For mCherry fluorescence analysis, similar conditions were used, but with the restrictions that the pixel values were greater than 200 and 1.9 standard deviations above cellular background. Fewer than four foci were identified if the top four maxima did not all pass the restrictions on pixel value.

To determine the YFP fluorescence in the neighborhood of CFP-LacI and TetR-mCherry foci, up to four maxima were identified in the CFP and mCherry images, and their positions were determined by the procedure described above. For each of these maxima, the software searched for the brightest YFP pixel within a 5-by-5 array of pixels centered on the CFP or mCherry maximum. A 5-by-5 array of pixels centered on this YFP maximum was then fit to a Gaussian function, C0 exp (−C1 × r2) + C2, as in reference 3. C0, C1, and C2 are fitting parameters, and r is the radius from the center of the array. The amplitude of this fit, C0, was used as the measure of the local fluorescence.

For the data in Fig. 4C, we discarded cells that lacked distinct foci. This was determined for each cell by performing a Gaussian fit, as described above, centered on the brightest YFP pixel. From visual inspection of images, distinct foci were determined to be those for which the quantity C1 was within the range 0.35 to 2.3.

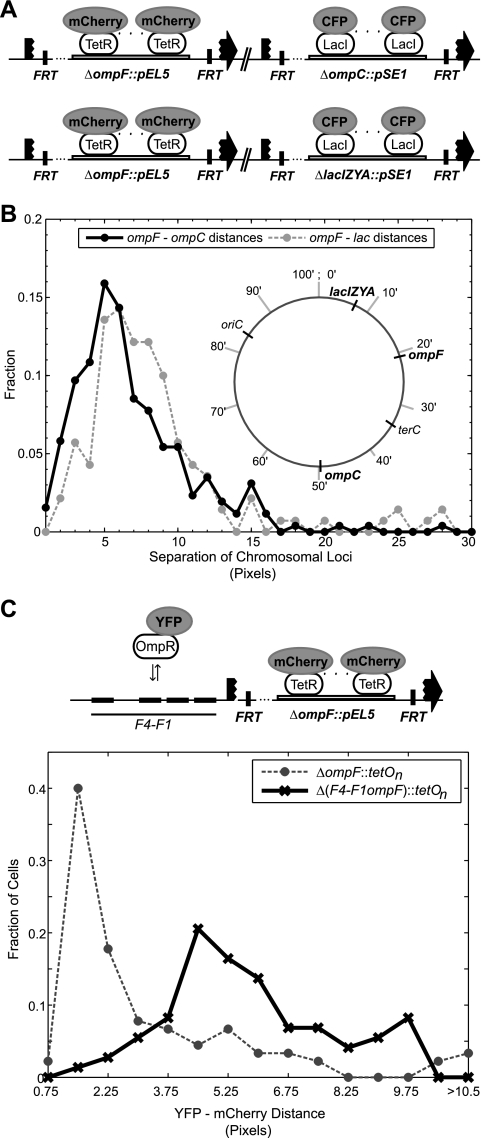

FIG. 4.

(A) Constructs integrated in the chromosome at ompF and ompC (EAL105) or ompF and lac (EAL85) to simultaneously image two loci. CFP-LacI and TetR-mCherry were expressed from pEL7. (B) Distribution of distances between chromosomal labels. (Inset) Chromosomal map positions of the three loci. The distributions give an ompF-ompC mean separation of 6.3 pixels ≈ 0.5 μm and an ompF-lac mean separation of 7.3 pixels ≈ 0.6 μm. In addition, approximately 13% of the distances between ompF and ompC and 10% of the distances between ompF and lac fall within 2.25 pixels, the cutoff distance used to score for colocalization (see text for details). (C) Effect of deleting the OmpR binding sites at ompF (F1 to F4) on the localization of the brightest OmpR-YFP spot. Histograms of distances between the brightest OmpR-YFP spot and the closest ompF chromosomal location (labeled with TetR-mCherry) in strains ± OmpR binding sites F1 to F4. The percentages of OmpR-YFP spots colocalizing (out to 2.25 pixels) with the nearest chromosomal locus are approximately 60% and 4% for the strains with and without sites F1 to F4, respectively. The strains are EAL105 (F1 to F4 intact) and EAL111 (F1-to-F4 deletion). CFP-LacI and TetR-mCherry were expressed from pEL7. To confine the analysis to the ompF locus, we excluded cells in which ompF and ompC (labeled with CFP-LacI) fell within 3.5 pixels of each other. Cells were further restricted to those with distinct foci, as described in Materials and Methods. This resulted in 136 distances from 182 cells of EAL105 and 73 distances from 196 cells of EAL111.

For Fig. 5 and 6, cells for which ompF and ompC loci fell within a drift radius of each other were discarded as follows. For each CFP or mCherry maximum in a given cell, the software reported the distance to the nearest maximum in the other fluorescence channel. CFP and mCherry maxima whose separations were within the drift radius of a chromosomal location over the longest time scale of image sequence collection were discarded as not being sufficiently well separated. Fluorescence intensities were normalized across different days using the parameter C0 from Gaussian fits to YFP fluorescence at random locations that were at least a distance of 5 pixels from the CFP-LacI and TetR-mCherry foci. We required random locations to fall within the region that was typically occupied by ompF and ompC, which was roughly the middle 70% of the major and minor axes. More precisely, we required the major and minor axis coordinates to fall within the region that is occupied by ompF and ompC 98% of the time (determined empirically for each growth condition). These Gaussian fits to random locations were used to background subtract and rescale the data. Images for figures were prepared using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). Images in Fig. 1 were normalized to the same average cellular fluorescence. Brightness and contrast levels were identical for all of the images in Fig. 1 and were adjusted in Fig. 2B and 3 to maximize visibility of localized fluorescence.

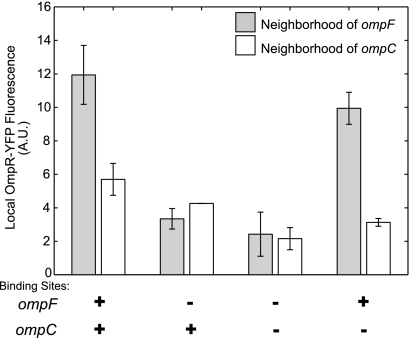

FIG. 5.

Quantification of OmpR-YFP fluorescence at chromosomal locations. Shown is OmpR-YFP fluorescence (arbitrary units [A.U.]) in the neighborhoods of ompF and ompC, in the presence or absence of OmpR binding sites. The local YFP fluorescence was determined from a Gaussian fit in the neighborhood of either ompF (gray bars) or ompC (white bars), as described in Materials and Methods. The data represent the mean and range of two independent experiments. Each mean value was computed from at least 130 measurements. From left to right, the strains are EAL105, EAL111, EAL112, and EAL113. CFP-LacI and TetR-mCherry were expressed from pEL7.

FIG. 6.

Effects of EnvZ/OmpR stimulation on OmpR-YFP fluorescence at ompF and ompC. (A) Effect of procaine on ompF and ompC transcription measured in the ompF-yfp and ompC-cfp reporter strain EPB273a. (B) Local OmpR-YFP fluorescence in the neighborhood of ompF (left) or ompC (right) ± 10 mM procaine. OmpR-YFP fluorescence was determined as in Fig. 5. The data represent the means and ranges of two experiments. The strains are EAL105, EAL111 (deletion of F1 to F4), and EAL113 (deletion of C1 to C3).

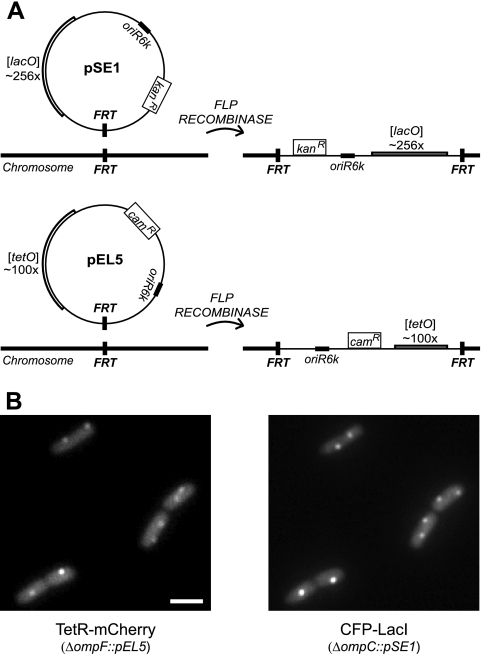

FIG. 2.

A system for inserting arrays of lac operators (lacO) and tet operators (tetO) into chromosomal FRT sites. (A) Plasmids pSE1 and pEL5 contain an oriR6Kγ origin of replication, a selectable marker conferring chloramphenicol or kanamycin resistance, and an FRT site, which is recognized by the FLP recombinase. Plasmid construction details are in Materials and Methods. (B) Fluorescence micrographs of cells containing both tetO and lacO arrays (TetR-mCherry fluorescence [left] and CFP-LacI fluorescence [right]). The strain EAL105 has pSE1 inserted at ompC and pEL5 inserted at ompF. (The plasmids were integrated into separate strains and then moved by P1 transduction.) TetR-mCherry and CFP-LacI were expressed from the plasmid pEL7. The scale bar represents 2 μm.

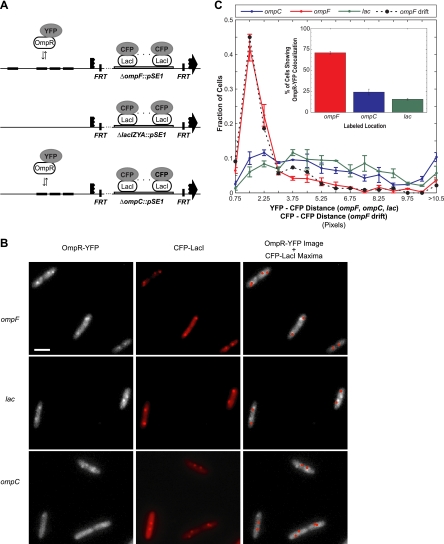

FIG. 3.

OmpR-YFP localization at ompF, ompC, and lac. (A) Constructs integrated in the chromosome at ompF (EAL70), ompC (EAL62), or lacI-lacA (EAL73) to assay colocalization with OmpR-YFP foci. The regulatory regions upstream of ompF and ompC have 4 and 3 OmpR binding sites, respectively. Each site is bound by an OmpR dimer. (B) Images of OmpR-YFP (left), CFP-LacI (middle), and OmpR-YFP, with the CFP-LacI local maxima from the middle image identified by red dots (right) for the three different strains described in panel A. LacI-CFP was expressed from pEB96. Scale bar represents 2 μm. (C) Colocalization of chromosomal loci with the brightest OmpR-YFP spot in each cell. Histograms of distances between the brightest OmpR-YFP spot and the closest labeled chromosomal location (CFP-LacI) in strains with labels at ompF, ompC, or lacI-lacA. The drift of the ompF locus (CFP-LacI) over 2 s is also shown for comparison (see text for discussion). Based on the drift distribution, colocalization was defined to be a YFP-CFP distance of less than 2.25 pixels. (Inset) Percentage of cells where OmpR-YFP is counted as colocalizing with a given gene locus. Each distribution represents the means of two independent experiments, and the bars denote the range. For each experiment, the distribution was determined from at least 130 cells. Strains and growth conditions are as in panel B. One pixel = 80 nm.

Porin transcription fluorescence assay.

CFP fluorescence expressed from the ompC promoter and YFP fluorescence expressed from the ompF promoter, for cultures growing with or without procaine, were determined by following the procedures described in reference 3.

RESULTS

A simple system for inserting lacO and tetO arrays into the chromosome.

To facilitate the targeted insertion of lac and tet operators into the chromosome, we constructed conditionally replicative plasmids: one containing arrays of lacO repeats (24) and a kanamycin resistance gene and the other containing tetO repeats (18) and a chloramphenicol resistance gene (Fig. 2A). These plasmids also contain recognition sequences (FRT sites) for the FLP recombinase. The plasmids can therefore be stably integrated into FRT sites in the E. coli chromosome by expressing FLP (9). Chromosomal FRT sites can be easily engineered in many organisms: e.g., by lambda Red-mediated recombination (6). For E. coli K-12, strains are available with an FRT site inserted in virtually any nonessential gene (2). Therefore, with this system one can easily target arrays of operators to almost any location in the E. coli chromosome and move the subsequent construct to other strain backgrounds by P1 transduction. Additionally, both lacO and tetO repeats can be moved into the same strain to simultaneously label two chromosomal locations (Fig. 2B).

Colocalization of OmpR-YFP foci with chromosomal loci.

To determine if the brightest OmpR-YFP foci colocalize with either ompF or ompC, chromosomal lacO repeats were inserted in place of ompF, ompC, or lacI-lacA (as a negative control) in a strain containing an ompR-yfp translational fusion (Fig. 3A). CFP-LacI was expressed from a plasmid. A comparison of sample CFP and YFP fluorescence images is shown in Fig. 3B. From visual inspection, a significant number of the OmpR-YFP foci show striking colocalization with ompF. The foci appear to be occasionally colocalized with ompC, as shown in the uppermost cell in Fig. 3B, third row. Colocalization with the lacI-lacA region, which has not been reported to have adjacent OmpR binding sites, appears to be less frequent. To quantitatively analyze the extent of colocalization, we developed software to identify the position of the brightest OmpR-YFP spot in each cell and determine its distance from the nearest CFP-LacI spot. The resulting histogram (Fig. 3C) is consistent with impressions from visual inspection of the images: the brightest OmpR-YFP foci show striking colocalization with ompF and relatively little colocalization with lacI-lacA and ompC.

For the microscope used in these experiments, there was a time lag of approximately 2 s between the acquisition of CFP and YFP images. This complicates the analysis of colocalization as individual chromosomal loci move within the cell over this time interval. Over the same time interval, the boundaries of cells do not show detectable motion, indicating that the observed motion is not due to drift of the sample. To characterize the drift of a chromosomal location, two successive CFP images of a field of cells were acquired 2 s apart. When repeated over many fields, the resulting distributions of displacements were found to be similar for the ompF, ompC, and lacI-lacA regions. The distribution for ompF is shown in Fig. 3C (dashed line). Seventy-three percent of the points in this distribution correspond to an ompF drift of less than 2.25 pixels (∼180 nm). We therefore chose a cutoff of 2.25 pixels as a conservative criterion for colocalization of OmpR-YFP and CFP-LacI foci. Thus, CFP and YFP fluorescence maxima were scored as colocalized if they were separated by a distance less than or equal to 2.25 pixels.

With this colocalization criterion, approximately 70% of the brightest OmpR-YFP foci colocalize with ompF, compared with approximately 15% colocalization with lacI-lacA (Fig. 3C, inset). The ompC locus shows an intermediate amount of colocalization with the brightest OmpR-YFP foci, at about 23%. Furthermore, we note that the distribution of ompF drift distances shows remarkable agreement with the distribution of distances between ompF locations and the brightest OmpR-YFP foci (Fig. 3C, compare red solid lines and black dashed lines). This indicates that the most prominent OmpR-YFP spots are in the vicinity of ompF.

Proximity of ompF to ompC and lacI-lacA.

The porin genes ompF and ompC, which share several common regulators, are separated by approximately 1,300 kb and are roughly symmetrically located around terC (Fig. 4B, inset). The lac locus is roughly half the distance to ompF (630 kb). To analyze the extent of ompF colocalization with ompC and lac, ompF was labeled with tetO repeats and ompC or lac was labeled with lacO repeats (Fig. 4A). Analysis of the distances between the chromosomal labels indicates that, with the same colocalization criteria described above, roughly 13% of the ompF labels colocalize with an ompC label and roughly 10% colocalize with a lac label (Fig. 4B). This suggests a significant fraction of the lac and ompC colocalization with OmpR-YFP in Fig. 3C can be accounted for by the colocalization of these loci with ompF.

OmpR-YFP colocalization is OmpR binding site dependent.

To test if the colocalization of the brightest OmpR-YFP foci with ompF is due to OmpR binding, we deleted the OmpR binding sites F1 to F4 upstream of ompF. This resulted in a marked shift in the distribution of distances between ompF and the brightest OmpR-YFP foci when compared with the corresponding distribution in a strain with the binding sites intact (Fig. 4C). In particular, deletion of the binding sites caused the brightest OmpR-YFP foci to fall farther from ompF on average; approximately 4% of the foci colocalize with ompF in the binding site deletion strain, whereas approximately 60% colocalize with ompF when the binding sites are intact (Fig. 4C). From visual inspection, we found that deletion of F1 to F4 resulted in many cells that did not show clear OmpR-YFP foci. This observation formed the basis for the analysis in the following sections. We also note that in Fig. 4C we restricted the analysis to only those cells with distinct foci (see Materials and Methods and the legend to Fig. 4C).

OmpR-YFP fluorescence at ompF and ompC is OmpR binding site dependent.

The OmpR-YFP foci correspond to a local increase in fluorescence (Fig. 1B). By studying their positions, we found the brightest foci are usually in the vicinity of ompF. In addition, this colocalization depends on adjacent OmpR binding sites. To further explore the association of OmpR-YFP with these sites, we measured the YFP fluorescence in the neighborhoods of ompF and ompC.

When ompF and ompC are spatially well separated, deletion of the OmpR binding sites at ompF should decrease the OmpR-YFP fluorescence at ompF, while leaving the fluorescence at ompC unchanged. To test this, and also to determine whether there is a similar effect at ompC, we compared four strains, with intact OmpR binding sites at ompF and ompC, a deletion of the sites at ompF, Δ(F1-F4), a deletion of the sites at ompC, Δ(C1-C3), or a deletion of both sets of sites, Δ(F1-F4) Δ(C1-C3). Fluorescence images were analyzed to determine the local YFP fluorescence in the neighborhood of ompF and ompC (see Materials and Methods for details).

When the binding sites at ompF were deleted, the fluorescence at ompF decreased but had relatively little effect on the fluorescence at ompC (Fig. 5). The effect of deleting binding sites at ompC, on the other hand, was relatively weak. When the binding sites at both ompF and ompC were deleted, the local OmpR-YFP fluorescence was comparable for the two locations. This suggests the average OmpR-YFP occupancy at the ompC promoter is lower than the occupancy at ompF under the growth conditions used in these experiments (minimal glucose medium). We also note that ompC transcription under these growth conditions is relatively low but can be significantly increased by stimulating the EnvZ/OmpR system with procaine (Fig. 6 A, right panel). If the increased ompC transcription from procaine stimulation were due to significantly increased OmpR binding to the ompC promoter, then we should also observe increased OmpR-YFP fluorescence at ompC. This is indeed the case, as is evident in Fig. 6B (right panel). Treatment with 10 mM procaine resulted in local fluorescence at ompC that was comparable to the level of ompF in untreated cells (Fig. 6B, compare left and right panels) Furthermore, the increase in local fluorescence at ompC was eliminated when the OmpR binding sites C1 to C3 were deleted. Procaine stimulation also produced an increase in fluorescence at ompF. The fold change is lower than for ompC, but the overall levels of fluorescence are higher (Fig. 6B, left panel). Procaine stimulation has the effect of repressing ompF transcription (Fig. 6A, left panel), as expected from higher levels of OmpR-YFP phosphorylation.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that the observed subcellular localization of OmpR-YFP results from OmpR-YFP binding specific sites in the chromosome. The wild-type expression level of OmpR-YFP gives considerable diffuse fluorescence in the cytoplasm, which would make single-molecule imaging difficult (Fig. 1). Single molecules of LacI-YFP have been imaged, but this required very low fluorescent protein expression levels (∼3 repressors/cell) (8). From our results, it appears that the multiple binding sites upstream of the porin genes ompF and ompC (which are maximally occupied by 8 and 6 OmpR molecules, respectively) can give sufficiently high local concentrations of OmpR-YFP to be easily detected by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1). The physical separation of ompF and ompC (Fig. 4B) made it possible to study the fluorescence, and therefore infer the relative extent of OmpR-YFP binding, at these locations individually.

Deletion of binding sites at ompF resulted in a marked decrease in local OmpR-YFP fluorescence (Fig. 5 and 6B). A similar effect was observed at ompC under conditions of EnvZ stimulation with procaine (Fig. 6B). In addition, treatment of cells with procaine resulted in a measurable local increase in OmpR-YFP at ompF and ompC. This suggests that the OmpR binding sites at these loci are not fully occupied in the absence of procaine treatment. We also note that when both binding sites at ompF and ompC were deleted, additional OmpR-YFP foci were evident, particularly when cells were treated with procaine (data not shown). It seems likely that these foci reflect OmpR-YFP binding at other OmpR-regulated genes in the chromosome. Further exploration of this question would require testing other OmpR-regulated genes for colocalization, which may require a more complete characterization of the OmpR regulon in E. coli.

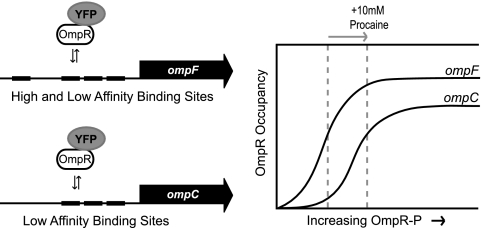

A model of hierarchical OmpR binding at the porin promoters has been proposed to account for the differential regulation of ompF and ompC (21, 25). In this model, the ompF regulatory region contains high- and low-affinity binding sites for OmpR-P and the ompC region contains only low-affinity sites (Fig. 7). OmpR-P primarily binds the high-affinity sites (at ompF) when its concentration is low. With increasing OmpR-P, additional binding occurs at the low-affinity sites (at ompF and ompC). Occupation of the high-affinity sites results in activation of ompF transcription. Occupation of the low-affinity sites results in repression of ompF and activation of ompC transcription. This model is consistent with in vitro studies reporting hierarchical and cooperative binding at the porin promoters (4, 14, 22).

FIG. 7.

Model of hierarchical OmpR-P binding at ompF and ompC. The regulatory region for ompF has a mixture of high-affinity and low-affinity OmpR binding sites; ompC only has low-affinity sites. A sketch of the resulting occupancy of the ompF and ompC promoters as a function of OmpR-P is shown on the right. The dashed lines represent OmpR-P occupancy, consistent with our observations for growth ± 10 mM procaine.

Based on the following observations, our data provide in vivo support for the above model. First, for the growth conditions used here—minimal glucose medium with or without procaine—we observed more OmpR-YFP at ompF than at ompC. This is consistent with greater overall OmpR-YFP binding at ompF. Second, stimulation of the EnvZ/OmpR system with procaine produced a larger fold change in fluorescence at ompC than at ompF (Fig. 6B), indicating the relative increase in OmpR-YFP binding at ompC is greater than at ompF when OmpR phosphorylation is greatly increased. Such behavior is consistent with a larger proportion of low-affinity OmpR binding sites at ompC than at ompF. A sketch of these observations, interpreted in the context of the hierarchical binding model, is shown in Fig. 7.

Our work demonstrates that the fluorescently labeled transcription factor OmpR-YFP, expressed at roughly wild-type levels, can be imaged binding native chromosomal loci. By quantifying this fluorescence localization at labeled sites of interest, we were able to study OmpR activity in live cells. This method may be applicable to the study of other transcription factors for which functional fluorescent protein fusions are available. We note that the quantification of fluorescence does not depend on the existence of distinct foci. However, it is necessary to know the approximate location where the transcription factor binds. The method is likely to be particularly useful at loci containing multiple binding sites, where the fluorescence of bound transcription factor is most likely to give a significant signal. We also developed a simple system for inserting arrays of lac and tet operators into chromosomal FRT sites. By using these constructs in conjunction with the Keio Collection of E. coli deletion strains, one can readily insert lacO and tetO arrays at virtually any location of the chromosome. The large collection of marked strains that can be rapidly constructed by this method will be useful for studies of other DNA binding proteins and aspects of chromosome organization.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NSF grant MCB0615957 (to M.G.). E. A. Libby was also supported by NIH Bacteriology training grant T32 AI060516.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 May 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Azam, T. A., S. Hiraga, and A. Ishihama. 2000. Two types of localization of the DNA-binding proteins within the Escherichia coli nucleoid. Genes Cells 5:613-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba, T., T. Ara, M. Hasegawa, Y. Takai, Y. Okumura, M. Baba, K. A. Datsenko, M. Tomita, B. L. Wanner, and H. Mori. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batchelor, E., and M. Goulian. 2006. Imaging OmpR localization in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1767-1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergstrom, L. C., L. Qin, S. L. Harlocker, L. A. Egger, and M. Inouye. 1998. Hierarchical and co-operative binding of OmpR to a fusion construct containing the ompC and ompF upstream regulatory sequences of Escherichia coli. Genes Cells 3:777-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherepanov, P. P., and W. Wackernagel. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158:9-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egger, L. A., H. Park, and M. Inouye. 1997. Signal transduction via the histidyl-aspartyl phosphorelay. Genes Cells 2:167-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elf, J., G. W. Li, and X. S. Xie. 2007. Probing transcription factor dynamics at the single-molecule level in a living cell. Science 316:1191-1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellermeier, C. D., A. Janakiraman, and J. M. Slauch. 2002. Construction of targeted single copy lac fusions using lambda Red and FLP-mediated site-specific recombination in bacteria. Gene 290:153-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerken, H., E. S. Charlson, E. M. Cicirelli, L. J. Kenney, and R. Misra. 2009. MzrA: a novel modulator of the EnvZ/OmpR two-component regulon. Mol. Microbiol. 72:1408-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffith, K. L., M. M. Fitzpatrick, E. F. Keen III, and R. E. Wolf, Jr. 2009. Two functions of the C-terminal domain of Escherichia coli Rob: mediating “sequestration-dispersal” as a novel off-on switch for regulating Rob's activity as a transcription activator and preventing degradation of Rob by Lon protease. J. Mol. Biol. 388:415-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haldimann, A., and B. L. Wanner. 2001. Conditional-replication, integration, excision, and retrieval plasmid-host systems for gene structure-function studies of bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 183:6384-6393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang, K. J., and M. M. Igo. 1996. Identification of the bases in the ompF regulatory region, which interact with the transcription factor OmpR. J. Mol. Biol. 262:615-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang, K. J., C. Y. Lan, and M. M. Igo. 1997. Phosphorylation stimulates the cooperative DNA-binding properties of the transcription factor OmpR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:2828-2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang, K. J., J. L. Schieberl, and M. M. Igo. 1994. A distant upstream site involved in the negative regulation of the Escherichia coli ompF gene. J. Bacteriol. 176:1309-1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitagawa, M., T. Ara, M. Arifuzzaman, T. Ioka-Nakamichi, E. Inamoto, H. Toyonaga, and H. Mori. 2005. Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA Res. 12:291-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maeda, S., and T. Mizuno. 1990. Evidence for multiple OmpR-binding sites in the upstream activation sequence of the ompC promoter in Escherichia coli: a single OmpR-binding site is capable of activating the promoter. J. Bacteriol. 172:501-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michaelis, C., R. Ciosk, and K. Nasmyth. 1997. Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell 91:35-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY.

- 20.Mizuno, T., M. Kato, Y. L. Jo, and S. Mizushima. 1988. Interaction of OmpR, a positive regulator, with the osmoregulated ompC and ompF genes of Escherichia coli. Studies with wild-type and mutant OmpR proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 263:1008-1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pratt, L. A., and T. J. Silhavy. 1995. Porin regulon of Escherichia coli, p. 105-127. In J. A. Hoch and T. J. Silhavy (ed.), Two-component signal transduction. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 22.Rampersaud, A., S. L. Harlocker, and M. Inouye. 1994. The OmpR protein of Escherichia coli binds to sites in the ompF promoter region in a hierarchical manner determined by its degree of phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 269:12559-12566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rampersaud, A., and M. Inouye. 1991. Procaine, a local anesthetic, signals through the EnvZ receptor to change the DNA binding affinity of the transcriptional activator protein OmpR. J. Bacteriol. 173:6882-6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinett, C. C., A. Straight, G. Li, C. Willhelm, G. Sudlow, A. Murray, and A. S. Belmont. 1996. In vivo localization of DNA sequences and visualization of large-scale chromatin organization using lac operator/repressor recognition. J. Cell Biol. 135:1685-1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russo, F. D., and T. J. Silhavy. 1991. EnvZ controls the concentration of phosphorylated OmpR to mediate osmoregulation of the porin genes. J. Mol. Biol. 222:567-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sciara, M. I., C. Spagnuolo, E. Jares-Erijman, and E. Garcia Vescovi. 2008. Cytolocalization of the PhoP response regulator in Salmonella enterica: modulation by extracellular Mg2+ and by the SCV environment. Mol. Microbiol. 70:479-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slauch, J. M., and T. J. Silhavy. 1996. The porin regulon: a paradigm for the two-component regulatory systems, p. 383-417. In E. C. C. Lin and A. S. Lynch (ed.), Regulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Chapman & Hall, New York, NY.

- 28.Taylor, R. K., M. N. Hall, and T. J. Silhavy. 1983. Isolation and characterization of mutations altering expression of the major outer membrane porin proteins using the local anaesthetic procaine. J. Mol. Biol. 166:273-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsung, K., R. E. Brissette, and M. Inouye. 1989. Identification of the DNA-binding domain of the OmpR protein required for transcriptional activation of the ompF and ompC genes of Escherichia coli by in vivo DNA footprinting. J. Biol. Chem. 264:10104-10109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villarejo, M., and C. C. Case. 1984. envZ mediates transcriptional control by local anesthetics but is not required for osmoregulation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 159:883-887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werner, J. N., E. Y. Chen, J. M. Guberman, A. R. Zippilli, J. J. Irgon, and Z. Gitai. 2009. Quantitative genome-scale analysis of protein localization in an asymmetric bacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:7858-7863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]