Abstract

We show that dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) inhibits Salmonella hilA expression and that this inhibition is stronger under anaerobiosis. Because DMSO can be reduced to dimethyl sulfide (DMS) during anaerobic growth, we hypothesized that DMS was responsible for hilA inhibition. Indeed, DMS strongly inhibited the expression of hilA and multiple Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1)-associated genes as well as the invasion of cultured epithelial cells. Because DMSO and DMS are widespread in nature, we hypothesize that this phenomenon may contribute to environmental sensing by Salmonella.

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is a human pathogen that causes self-limiting gastroenteritis that can develop into life-threatening infections in immunocompromised individuals. The infection begins through ingestion of contaminated food or water. Following its ingestion, S. Typhimurium attaches to intestinal epithelial cells and induces cytoskeletal rearrangements that result in their engulfment. Once inside host cells, S. Typhimurium modifies the phagosome to allow bacterial survival and replication in an otherwise hostile environment. These two major accomplishments by S. Typhimurium are attributed to two independent type 3 secretion systems encoded within Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) and SPI-2. These secretion machineries serve to inject effector proteins directly into the host cell cytosol, where they function to subvert host defenses. SPI-1 is required for the invasion of nonphagocytic cells, whereas SPI-2 is involved in survival under the harsh conditions encountered in the phagosome (9, 12, 13).

The invasion of host cells by S. Typhimurium is controlled by a complex cascade of regulatory proteins. One of the major players in the control of invasion gene expression is the OmpR/ToxR-type transcriptional regulator HilA (17). The expression of hilA is affected by a plethora of factors, and it is generally accepted that hilA represents a central hub through which environmental conditions can be sensed and translated into the regulation of genes responsible for host cell invasion (1, 6, 16). Multiple cues affecting the expression of hilA have been identified to date. For instance, hilA expression is affected by osmolarity, pH, and oxygen tension (1). It has been hypothesized that the ability to sense such cues might provide S. Typhimurium the advantage of recognizing the host environment and adapting accordingly (1). Given the complexity of the host environment, it is reasonable to imagine that many other cues are sensed by S. Typhimurium during infection and that the bacteria could take advantage of this process.

DMSO inhibits hilA expression.

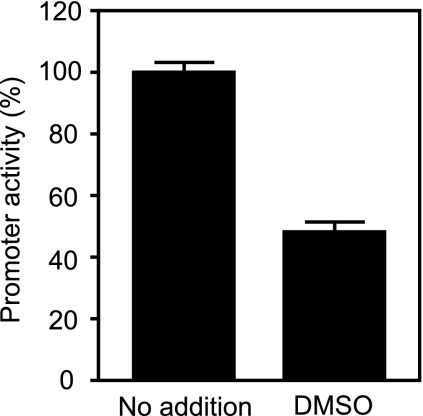

We initiated this study by screening a library of compounds to identify inhibitors of S. Typhimurium virulence gene expression. To do so, we used a reporter strain containing a fusion between the promoter of hilA and a gene encoding the green fluorescent protein (gfp). To construct promoter fusions, the entire intergenic region between hilA and its upstream neighboring gene was PCR amplified using chromosomal DNA from the streptomycin-resistant S. Typhimurium strain SL1344 (27) as template and PfuTurbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sequences of the primers used are available upon request. The PCR products were purified, digested with SacI and BamHI, and ligated into similarly digested pFPV25 plasmid by use of standard cloning procedures (20). BamHI and T4 DNA ligase were obtained from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). SacI was obtained from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Purification of chromosomal DNA, plasmids, and PCR products was done using Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) kits according to the manufacturer's recommendations. pFPV25 contains a promoterless gfp gene downstream of a multicloning site and confers carbenicillin resistance (24). While testing the chemical library using the hilA reporter strain, we serendipitously identified the solvent in which the compounds were resuspended, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), as an inhibitor of hilA expression. To measure the effect of DMSO on gene expression, mid-logarithmic-phase cultures of S. Typhimurium SL1344 containing the reporter plasmid were subcultured to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05 in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing 100 μg/ml of carbenicillin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 275 mM DMSO (≥99.9% pure; Sigma-Aldrich). To avoid degradation, DMSO was used within 5 months of purchase. After 4 h of incubation at 37°C with shaking at 225 rpm, the cultures had reached the late logarithmic phase of growth and the OD and fluorescence were measured using a 96-well plate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). As shown in Fig. 1, growth in the presence of DMSO inhibited hilA expression by approximately 52%.

FIG. 1.

DMSO inhibits hilA expression. The activity of the hilA promoter in cultures grown in the presence of 275 mM DMSO is shown as a percentage of the activity in cultures grown in the absence of DMSO. The results shown represent the averages for five replicates. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means.

The inhibition of hilA expression is more pronounced under anaerobic conditions.

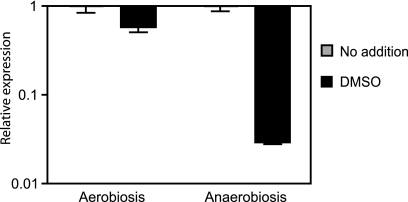

To investigate if the inhibition of hilA expression observed using our reporter system represented a real reduction in hilA transcript levels, we compared the levels of hilA transcript in the absence and presence of DMSO through real-time PCR (RT-PCR). Additionally, in order to investigate whether the inhibition of hilA by DMSO could be observed under other physiological conditions, we compared the effects of DMSO on hilA transcript levels during aerobic and anaerobic growth. Aerobic growth was achieved essentially as described above. For anaerobic growth, overnight cultures of S. Typhimurium were diluted 1:200 and allowed to grow for 18 h. Anaerobiosis was achieved using the GasPak EZ anaerobe container system (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and anaerobic jars. Cultures were incubated with shaking (150 rpm) to facilitate gas exchange. After incubation, RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and RT-PCR were performed using Qiagen kits according to the manufacturer's instructions. RT-PCR was done using 40-cycle runs on the Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) 7500 system. The results were normalized using the expression levels of the housekeeping gene gapA, encoding the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase enzyme (19). Confirming our reporter studies, DMSO inhibited hilA expression by 42% (1.7-fold inhibition) (Fig. 2), suggesting that the phenomenon observed is a consequence of decreased hilA transcript levels. Interestingly, when S. Typhimurium was grown anaerobically, inhibition of hilA by DMSO was extremely more pronounced; under anaerobiosis, hilA was inhibited over 97% by DMSO (34.2-fold inhibition) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

The effect of DMSO on hilA expression is more pronounced during anaerobic growth. Transcript levels of hilA in cultures grown in the absence or presence of 275 mM DMSO were assessed by RT-PCR. Transcript levels from cultures without DMSO were normalized to 1, and the results from cultures grown in the presence of DMSO were normalized accordingly. In the absence of DMSO, hilA was expressed at relatively high levels; the average numbers of cycles required for hilA detection were 18.6 for aerobic and 20.1 for anaerobic cultures. For comparison purposes, gapA detection occurred after 16.2 cycles during aerobic growth and after 19 cycles during anaerobic growth. The results shown represent the averages for five (aerobiosis) or six (anaerobiosis) replicates. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means.

DMS is a stronger inhibitor of invasion gene expression.

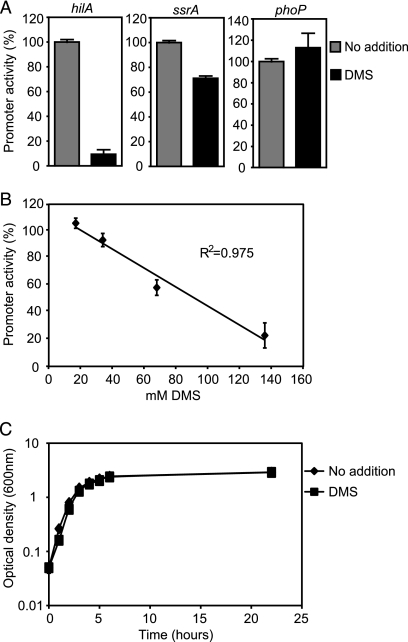

DMSO can be used as an electron acceptor by multiple bacterial species when grown anaerobically, generating dimethyl sulfide (DMS) (28, 29). Due to the fact that the inhibition of hilA by DMSO was sharply accentuated by anaerobic growth, we hypothesized that the real culprit in the inhibition of hilA was DMS and not DMSO. To investigate this, we measured the expression of hilA using the reporter strain grown in the presence or absence of 135 mM DMS (≥99% pure; Sigma-Aldrich). For this experiment, cultures were treated as described for experiments with DMSO. To avoid degradation, DMS was used within 5 months of purchase. In agreement with our hypothesis, we noticed that DMS caused a much greater inhibition of hilA expression than DMSO, even though the concentration used was less than half of that used for DMSO (Fig. 3 A). To us, this suggests that the effect of DMSO on hilA expression observed could be due to low levels of DMSO reduction, and therefore DMS production, by aerobically grown S. Typhimurium. As controls, we also measured the effect of DMS on the expression of ssrA and phoP, two other major virulence factor regulators (8, 10, 14, 18, 25), and showed that they are mostly unaffected by DMS. Also, in order to determine if there is a direct correlation between the levels of DMS present in the culture medium and hilA inhibition, we compared levels of hilA expression in cultures grown with different amounts of DMS. As shown in Fig. 3B, there is a linear relationship between the levels of DMS present in the cultures and the inhibition of hilA expression, showing that the effect of DMS on hilA expression is dose dependent. Additionally, in order to ensure that the inhibition of hilA is not a consequence of an effect of DMS on bacterial growth, we followed the growth of S. Typhimurium for several hours in the absence or presence of DMS by monitoring the ODs of cultures. Inoculation of cultures and OD measurements were performed as described above. Our results showed that DMS has no appreciable effect on bacterial growth (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

DMS inhibits hilA expression. (A) The expression of hilA in bacterial cultures grown in the absence or presence of 135 mM DMS using the reporter strain was measured. The results are shown as percentages of the activity of cultures grown in the absence of DMS and represent the averages for three (ssrA and phoP) or eight (hilA) replicates. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. (B) The effect of DMS on hilA expression is dose dependent. The activity of the reporter strain in the presence of the indicated DMS concentrations was monitored and is shown as percentage of the activity of cultures grown in the absence of DMS. The results shown represent the averages for six replicates. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means. (C) The effect of DMS on hilA expression is not due to an effect on bacterial fitness. Growth of S. Typhimurium in the absence or presence of 135 mM DMS was monitored over time through optical density (600 nm) measurements. The results shown represent the averages for five replicates. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means.

DMS inhibits the expression of multiple SPI-1-related genes.

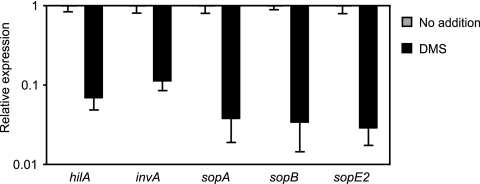

As previously mentioned, hilA is the major regulator of SPI-1 and associated effectors (1, 6, 16). To confirm that the effect of DMS on hilA expression impinges upon the expression of SPI-1-associated genes, we performed RT-PCR to compare the transcript levels of hilA, invA, sopA, sopB, and sopE2 (13) from S. Typhimurium cultures grown in the absence and presence of DMS. As expected, the expression of all SPI-1-related genes was strongly inhibited by DMS (Fig. 4), confirming that DMS can exert a negative effect on the expression of multiple invasion genes.

FIG. 4.

DMS inhibits multiple SPI-1-associated genes. Transcript levels of SPI-1-associated genes in cultures grown in the absence or presence of 135 mM DMS were assessed by RT-PCR. Transcript levels from cultures without DMS were normalized to 1, and the results from cultures grown in the presence of DMS were normalized accordingly. In the absence of DMS, all genes were expressed at relatively high levels; the average numbers of cycles required for detection were 18.7 for hilA, 24.1 for invA, 17.2 for sopA, 14.3 for sopB, and 15.9 for sopE2. For comparison purposes, gapA detection occurred after 16.2 cycles. The results shown represent the averages for five replicates. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means.

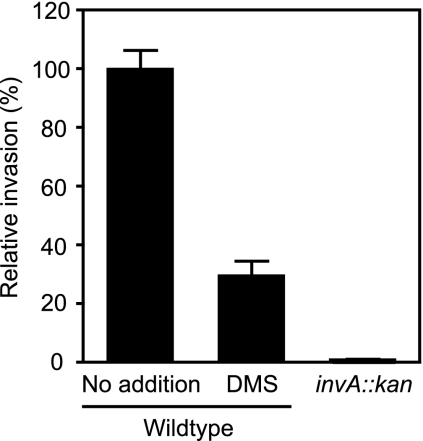

DMS inhibits host cell invasion by S. Typhimurium.

HilA is the master regulator of SPI-1, which carries genes that allow S. Typhimurium to actively invade host cells. To investigate whether or not the inhibition of hilA and SPI-1-related genes by DMS is reflected in the invasiveness of S. Typhimurium, we performed invasion assays and compared the abilities of bacterial cells grown in the absence and presence of the compound to invade cultured epithelial cells. HeLa cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with a high glucose concentration, 4 mM l-glutamine, and sodium pyruvate (HyClone, Waltham, MA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone), 1% nonessential amino acids (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) and 1% GlutaMAX (Gibco). Cells were seeded 24 h before infection in 24-well plates at a density of 7 × 104 cells per well. Inoculation of S. Typhimurium cultures was done as previously described. For invasion assays, cells in late-logarithmic-phase growth were spun down and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove DMS-containing medium and diluted in tissue culture medium. HeLa cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 10 for 10 min at 37°C and 5% CO2. Subsequently, cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 in growth medium containing 50 μg/ml gentamicin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h 50 min. After a total of 2 h of infection, HeLa cells were washed once with PBS and lysed in 250 μl of 1% Triton X-100 (BDH, Yorkshire, United Kingdom), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich). Serial dilutions were plated on LB plates containing 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). As we expected, growth in the presence of DMS causes a reduction in the invasion of cultured epithelial cells of over 70% (Fig. 5). As a control, we tested an invasion-deficient (invA::kan) mutant (7) and showed that its invasion was drastically reduced, as expected.

FIG. 5.

DMS inhibits S. Typhimurium host cell invasion. Invasion was assessed through a standard gentamicin protection assay (see text). The invasions of host cells were compared using S. Typhimurium cultures grown in the absence or presence of 135 mM DMS. The result for an invasion-deficient (invA::kan) mutant is shown for comparison. The results shown represent the averages for eight (wild-type) or three (mutant) replicates. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means.

Concluding remarks.

DMSO and DMS are widespread in nature and are important components of the global sulfur cycle, with DMS being the most abundant volatile sulfur compound in the atmosphere. DMS is produced by terrestrial and marine organisms and quickly evaporates to the atmosphere, where it can undergo photochemical oxidation to become DMSO. DMSO then returns to Earth in rain (3, 5). The biological significance of DMSO and DMS is mostly unknown. However, both of these compounds can be produced and degraded by a large array of microbes (11, 28, 29). DMS can be produced from various molecules, such as DMSO, methionine, S-methylmethionine, methanethiol, and dimethylsulfoniopropionate, most of which can be directly linked to bacterial amino acid metabolism (4, 21-23). Some of these reactions rely on the activity of DMSO reductase enzymes, which are present in several bacterial species. Of interest, the S. Typhimurium genome encodes several DMSO reductases (Comprehensive Microbial Resource [http://cmr.jcvi.org/tigr-scripts/CMR/CmrHomePage.cgi]), although the reason for the maintenance of such enzymes in spite of evolutionary pressures remains unknown. The invasion of epithelial cells is a hallmark of infection by S. Typhimurium and is mediated by virulence genes located on SPI-1 as well as effectors that are secreted through the SPI-1 secretion system but located outside this pathogenicity island (12, 13). A major modulator of transcription of SPI-1-associated genes is HilA, which plays a central role in sensing environmental cues and controlling the expression of virulence genes in response to such cues (1, 16, 17). Here, we show that DMS inhibits invasion gene expression in S. Typhimurium. Bacterial growth in the presence of this compound inhibits the expression of hilA as well as SPI-1-related genes, whereas other S. Typhimurium virulence genes, such as ssrA and phoP, are largely unaffected. Besides affecting invasion gene expression, DMS also inhibits S. Typhimurium invasion of cultured epithelial cells. It is important to mention that millimolar concentrations of the compound were required to achieve such effects. This suggests that DMS does not act as a microbial bona fide signal but, rather, as an environmental chemical cue. Whether DMS achieves millimolar concentrations in niches occupied by S. Typhimurium is unknown. However, this may be possible in environments where DMS is produced and diffusion is limited. Interestingly, some of the bacterial species known to produce DMS are found in the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and other animals, suggesting that S. Typhimurium may encounter this compound during the colonization of hosts (15, 26). In fact, DMS can be found in the feces and urine of mammals (23). Our study unveiled an additional level of environmental sensing and response by S. Typhimurium through regulation of hilA. Although at this point the exact significance of DMS(O) sensing by S. Typhimurium is unknown, the maintenance of multiple DMSO reductases in this organism suggests that the capacity to respire DMSO must offer a selective advantage under certain conditions. In fact, DMSO respiration has previously been shown to affect the virulence of a bacterial pathogen (2). Our study may be a step toward understanding the biological significance of microbial DMSO respiration and DMS production.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to the anonymous scientists who reviewed the manuscript for their insightful comments and constructive criticism.

This work was funded by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of Canada. L.C.M.A. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. M.M.C.B. is supported by a graduate scholarship from the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. S.D.A. is supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Human Frontier Science Program. R.B.R.F. is funded by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. B.B.F. is an HHMI International Research Scholar and a University of British Columbia Peter Wall Distinguished Professor.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bajaj, V., R. L. Lucas, C. Hwang, and C. A. Lee. 1996. Co-ordinate regulation of Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes by environmental and regulatory factors is mediated by control of hilA expression. Mol. Microbiol. 22:703-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baltes, N., I. Hennig-Pauka, I. Jacobsen, A. D. Gruber, and G. F. Gerlach. 2003. Identification of dimethyl sulfoxide reductase in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and its role in infection. Infect. Immun. 71:6784-6792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentley, R., and T. G. Chasteen. 2004. Environmental VOSCs—formation and degradation of dimethyl sulfide, methanethiol and related materials. Chemosphere 55:291-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilous, P. T., and J. H. Weiner. 1985. Dimethyl sulfoxide reductase activity by anaerobically grown Escherichia coli HB101. J. Bacteriol. 162:1151-1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charlson, R. J., J. E. Lovelock, M. O. Andreae, and S. G. Warren. 1987. Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulphur, cloud albedo and climate. Nature 326:655-661. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellermeier, J. R., and J. M. Slauch. 2007. Adaptation to the host environment: regulation of the SPI1 type III secretion system in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:24-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galan, J. E., and R. Curtiss III. 1991. Distribution of the invA, -B, -C, and -D genes of Salmonella typhimurium among other Salmonella serovars: invA mutants of Salmonella typhi are deficient for entry into mammalian cells. Infect. Immun. 59:2901-2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galan, J. E., and R. Curtiss III. 1989. Virulence and vaccine potential of phoP mutants of Salmonella typhimurium. Microb. Pathog. 6:433-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grassl, G. A., and B. B. Finlay. 2008. Pathogenesis of enteric Salmonella infections. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 24:22-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groisman, E. A., E. Chiao, C. J. Lipps, and F. Heffron. 1989. Salmonella typhimurium phoP virulence gene is a transcriptional regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:7077-7081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanlon, S. P., R. A. Holt, G. R. Moore, and A. G. McEwan. 1994. Isolation and characterization of a strain of Rhodobacter sulfidophilus: a bacterium which grows autotrophically with dimethylsulphide as electron donor. Microbiology 140:1953-1958. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen-Wester, I., and M. Hensel. 2001. Salmonella pathogenicity islands encoding type III secretion systems. Microbes Infect. 3:549-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haraga, A., M. B. Ohlson, and S. I. Miller. 2008. Salmonellae interplay with host cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:53-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hensel, M., J. E. Shea, S. R. Waterman, R. Mundy, T. Nikolaus, G. Banks, A. Vazquez-Torres, C. Gleeson, F. C. Fang, and D. W. Holden. 1998. Genes encoding putative effector proteins of the type III secretion system of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 are required for bacterial virulence and proliferation in macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 30:163-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horinouchi, M., K. Kasuga, H. Nojiri, H. Yamane, and T. Omori. 1997. Cloning and characterization of genes encoding an enzyme which oxidizes dimethyl sulfide in Acinetobacter sp. strain 20B. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 155:99-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones, B. D. 2005. Salmonella invasion gene regulation: a story of environmental awareness. J. Microbiol. 43:110-117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, C. A., B. D. Jones, and S. Falkow. 1992. Identification of a Salmonella typhimurium invasion locus by selection for hyperinvasive mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:1847-1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller, S. I., A. M. Kukral, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1989. A two-component regulatory system (phoP phoQ) controls Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:5054-5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson, K., T. S. Whittam, and R. K. Selander. 1991. Nucleotide polymorphism and evolution in the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (gapA) in natural populations of Salmonella and Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:6667-6671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 21.Sreekumar, R., Z. Al-Attabi, H. C. Deeth, and M. S. Turner. 2009. Volatile sulfur compounds produced by probiotic bacteria in the presence of cysteine or methionine. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 48:777-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka, K., and K. Nakamura. 1964. Metabolism of S-methylmethionine. I. Bacterial degradation of S-methylmethionine. J. Biochem. 56:172-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tangerman, A. 2009. Measurement and biological significance of the volatile sulfur compounds hydrogen sulfide, methanethiol and dimethyl sulfide in various biological matrices. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 877:3366-3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valdivia, R. H., and S. Falkow. 1996. Bacterial genetics by flow cytometry: rapid isolation of Salmonella typhimurium acid-inducible promoters by differential fluorescence induction. Mol. Microbiol. 22:367-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valdivia, R. H., and S. Falkow. 1997. Fluorescence-based isolation of bacterial genes expressed within host cells. Science 277:2007-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiner, J. H., R. A. Rothery, D. Sambasivarao, and C. A. Trieber. 1992. Molecular analysis of dimethylsulfoxide reductase: a complex iron-sulfur molybdoenzyme of Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1102:1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wray, C., and W. J. Sojka. 1978. Experimental Salmonella typhimurium infection in calves. Res. Vet. Sci. 25:139-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zinder, S. H., and T. D. Brock. 1978. Dimethyl sulfoxide as an electron acceptor for anaerobic growth. Arch. Microbiol. 116:35-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zinder, S. H., and T. D. Brock. 1978. Dimethyl sulphoxide reduction by micro-organisms. J. Gen. Microbiol. 105:335-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]