Abstract

In this study, the carotenoid biosynthetic pathways of Brevibacterium linens DSMZ 20426 were reconstructed, redesigned, and extended with additional carotenoid-modifying enzymes of other sources in a heterologous host Escherichia coli. The modular lycopene pathway synthesized an unexpected carotenoid structure, 3,4-didehydrolycopene, as well as lycopene. Extension of the novel 3,4-didehydrolycopene pathway with the mutant Pantoea lycopene cyclase CrtY2 and the Rhodobacter spheroidene monooxygenase CrtA generated monocyclic torulene and acyclic oxocarotenoids, respectively. The reconstructed β-carotene pathway synthesized an unexpected 7,8-dihydro-β-carotene in addition to β-carotene. Extension of the β-carotene pathway with the B. linens β-ring desaturase CrtU and Pantoea β-carotene hydroxylase CrtZ generated asymmetric carotenoid agelaxanthin A, which had one aromatic ring at the one end of carotene backbone and one hydroxyl group at the other end, as well as aromatic carotenoid isorenieratene and dihydroxy carotenoid zeaxanthin. These results demonstrate that reconstruction of the biosynthetic pathways and extension with promiscuous enzymes in a heterologous host holds promise as a rational strategy for generating structurally diverse compounds that are hardly accessible in nature.

Carotenoids, which are produced by many microorganisms and plants, belong to a class of pigment chemicals found in nature. These structurally diverse pigments have different biological functions such as coloration, photo protection, light-harvesting, and precursors for many hormones (3, 22). Carotenoids are commercially used as food colorants, animal feed supplements and, more recently, as nutraceuticals and as cosmetic and pharmaceutical compounds (19). Currently, only a few carotenoids can be produced commercially by chemical synthesis, fermentation, or isolation from a few abundant natural sources (13). The increasing industrial importance of carotenoids has led to renewed efforts to develop bioprocesses for large-scale production of a range of carotenoids, including lycopene, β-carotene, and more structurally diverse carotenoids (17, 21, 30, 31, 34). Interestingly, a recent study showed that carotenoids with more diverse structures tend to have higher biological activity than simple structures (1).

Previously, in vitro evolution altered the catalytic functions of the carotenoid enzymes phytoene desaturase CrtI and lycopene cyclase CrtY (Fig. 1) and produced novel carotenoid structures of tetradehydrolycopene and torulene in Escherichia coli (27). Furthermore, these in vitro evolved pathways and redesigned C30 carotenoid biosynthetic pathways were successfully extended with additional, wild-type carotenoid modifying enzymes and evolved enzymes (21), generating novel carotenoid structures (26).

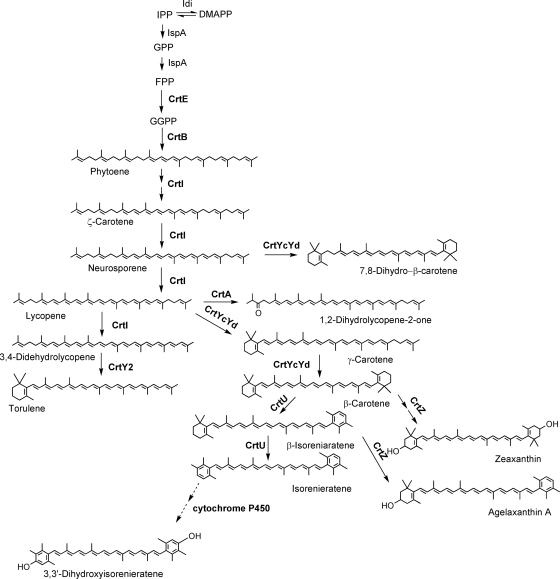

FIG. 1.

Reconstructed and redesigned B. linens carotenoid biosynthetic pathway in the heterologous host E. coli. Carotenogenic enzymes of B. linens, P. ananatis, and R. capsulatus, which were used for the biosynthetic pathway reconstruction, are indicated by boldface letters. Idi (IPP isomerase), IspA (FPP synthase), CrtE (GGPP synthase), CrtB (phytoene synthase), CrtI (phytoene desaturase), CrtYcYd (lycopene cyclase), CrtU (β-carotene desaturase), CrtZ (β-carotene hydrolase), CrtY2 (mutant lycopene cyclase), and CrtA (spheroidene monooxygenase). B. linens 3,3′-dihydroxyisorenieratene biosynthesis is indicated by dashed arrows.

Beside in vitro evolution (23, 34), combinatorial biosynthesis with carotenoid-modifying enzymes in a heterologous host has often been used to generate structurally novel carotenoids (24, 32). This combinatorial biosynthetic approach basically relies on the functional coordination of pathway enzymes from different sources in a heterologous host (5, 19, 35). Carotenogenic enzymes tend to be promiscuous in their substrate specificity (33) and show unexpected/hidden activities (20) when expressed in heterologous host microorganisms. One example is the unusual activity of diapophytoene desaturase CrtN in E. coli, which resulted in structurally novel compounds (20). Therefore, utilizing the promiscuity of carotenogenic enzymes makes combinatorial biosynthesis one of the most powerful strategies to generate structurally novel carotenoids that cannot be accessed in nature.

Yellow colored Brevibacterium linens is commonly used as a food colorant by the cheese industry (15). Interestingly, B. linens is known to synthesize aromatic ring-containing carotenoids, isorenieratene and its hydroxy derivatives (6, 7, 16). They are produced by seven carotenogenic enzymes expressed in B. linens: GGPP synthase CrtE, phytoene synthase CrtE, phytoene desaturase CrtI, lycopene cyclase CrtYcYd, β-carotene desaturase CrtU, and the cytochrome P450 (Fig. 1). Even though the carotenoid biosynthetic pathways of B. linens have been recently studied (6, 10), there have been no systematic functional study of downstream enzymes such as lycopene cyclase CrtYcYd in the biosynthetic pathway of B. linens in a heterologous environment.

Therefore, in the present study, for the first time we reconstructed, redesigned, and rationally extended the B. linens carotenoids biosynthetic pathway in E. coli to investigate the flexibility of the pathway enzymes in a heterologous host. Using this approach, we obtained an unexpected structure 3,4-didehydrolycopene, 7,8-dihydro-β-carotene, torulene, and the asymmetric carotenoid, agelaxanthin A, from engineered B. linens carotenoid pathways in E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gene cloning.

crtE, crtB, crtI, crtYcYd, crtU, ORF10 encoding cytochrome P450 of B. linens DSMZ 20426, crtA of Rhodobacter capsulatus DSMZ 1710, and crtZ of Pantoea ananatis (formerly Erwinia uredovora) DSMZ 30080 were amplified by PCR using a 5′ primer containing a XbaI restriction enzyme site followed by an optimized Shine-Dalgarno sequence (underlined) and a start codon (indicated in boldface; 5′-AGGAGGATTACAAAATG-3′), and a 3′ primer containing a EcoRI or NotI restriction enzyme site at its 5′ end (see the supplemental material). PCR products were purified by using a PCR product purification kit (Intron, Korea) or a gel extraction kit (Intron, Korea) and digested with the corresponding restriction enzymes (New England Biolabs). Purified insert DNAs were ligated into corresponding restriction enzyme sites of the plasmid pUCM, which had a modified constitutive lac promoter and new restriction enzyme sites (XbaI, AvaI, XmaI, SmaI, EcoRI, NcoI, NotI, and ApaII). pUCM is a high-copy-number plasmid pUC19 derivative that is devoid of the lacZ fragment region using PCR primers (5′-CCG GAA TTC CCA TGG GCG GCC GC TGC GGT ATT TTC TCC-3′ and 5′-CCG GAA TTC CCC GGG CGC TCT AGA CGC TCA CAA TTC CAC ACA-3′). To assemble a lycopene biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli, crtE was subcloned into the BamHI and HindIII sites of pACYC184, resulting in pACM-EBL; crtB was subcloned into the BamHI site of pACYC184, resulting in pACM-BBL; and crtI was subcloned into the HindIII site of pACYC184, resulting in pACM-IBL by amplification of the genes together with the modified constitutive lac-promoter, using primers that introduce corresponding restriction enzyme sites at both ends (Table 1) . Next, the crtB module from pUCM-BBL was subcloned into pACM-EBL to generate plasmid pACM-EBL-BBL, which express CrtE and CrtB together. Similarly, the crtI module from pUCM-IBL and the crtB module from pUCM-BBL were subcloned into pACM-EBL and pACM-IBL to generate two plasmids: pACM-EBL-IBL expressing CrtE and CrtI together and pACM-BBL-IBL expressing CrtB and CrtI together. The functionality of the resulting synthetic modules consisting of two genes was examined by complementation with the third gene, for example, complementing CrtE on pUCM-EBL with a synthetic module of CrtB and CrtI on pACM-BBL-IBL. Finally, the third crtI gene was functionally assembled into pACM-EBL-BBL, resulting in the plasmid pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL. To reconstruct the β-carotene biosynthesis pathway, crtYcYd was subcloned into the PpuMI site of pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL, resulting in pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL. Amplification of genes was performed by using the Vent polymerase (New England Biolabs), and the T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) was used for the ligation reaction.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant properties | Source or referencea |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| B. linens | C40 carotenoid pathway | DSMZ 20426 |

| P. ananatis | C40 carotenoid pathway | DSMZ 30080 |

| R. capsulatus | C40 carotenoid pathway | DSMZ 1710 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC19 | Cloning vector; inducible lac promoter, Ap | NEB |

| pUCM | Cloning vector modified from pUC19; constitutive lac promoter, Ap | This study |

| pACYC184 | Cloning vector, Cm | NEB |

| pUCM-EBL | Constitutively expressed crtE gene of B. linens | This study |

| pUCM-BBL | Constitutively expressed crtB gene of B. linens | This study |

| pUCM-IBL | Constitutively expressed crtI gene of B. linens | This study |

| pUCM-YBL | Constitutively expressed crtY gene of B. linens | This study |

| pUCM-UBL | Constitutively expressed crtU gene of B. linens | This study |

| pUCM-P450BL | Constitutively expressed cytochrome P450 gene of B. linens | This study |

| pUCM-ZPAN | Constitutively expressed crtZ gene of P. ananatis | This study |

| pUCM-ARC | Constitutively expressed crtA gene of R. capsulatus | This study |

| pUC-crtY2 | Constitutively expressed in vitro evolved crtY2 gene | 27 |

| pUC19-UBL-P450 | Inducibly expressed both crtU and cytochrome P450 gene of B. linens | This study |

| pUC19-UBL-ZPAN | Inducibly expressed both crtU of B. linens and crtZ gene of P. ananatis | This study |

| pACM-EBL | Constitutively expressed crtE gene of B. linens on pACYC184 | This study |

| pACM-BBL | Constitutively expressed crtB gene of B. linens on pACYC184 | This study |

| pACM-IBL | Constitutively expressed crtI gene of B. linens on pACYC184 | This study |

| pACM-EBL-BBL | Constitutively expressed crtE and crtB genes of B. linens on pACYC184 | This study |

| pACM-EBL-IBL | Constitutively expressed crtE and crtI genes of B. linens on pACYC184 | This study |

| pACM-BBL-IBL | Constitutively expressed crtB and crtI genes of B. linens on pACYC184 | This study |

| pAC-crtE-crtB-crtI14 | Constitutively expressed crtE, crtB, and crtI14 genes of P. ananatis produce 3,4,3′,4′-tetradehydrolycopene, as well as lycopene | 27 |

| pAC-crtE-crtB-crtI | Constitutively expressed crtE, crtB, and crtI genes of P. ananatis to produce lycopene | 27 |

| pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL | Constitutively expressed crtE, crtB, and crtI genes of B. linens on pACYC184 to produce lycopene | This study |

| pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL | Constitutively expressed crtE, crtB, crtI, and crtY genes of B. linens on pACYC184 to produce β-carotene | This study |

NEB, New England Biolabs.

Culture growth and isolation of carotenoids.

For carotenoid production, recombinant E. coli SURE cells harboring the carotenogenic plasmids were cultivated in 100 ml of Terrific Broth (TB) medium supplemented with the appropriate selective antibiotics chloramphenicol (50 μg/ml) and/or ampicillin (100 μg/ml) for 48 h at 30°C with 250 rpm. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation (4°C, 4,000 rpm) and extracted repeatedly with a total volume of 15 ml of acetone until all visible pigments were extracted. After centrifugation (4°C, 4,000 rpm), the colored supernatants were pooled and reextracted with an equal volume of hexane after the addition of an equal volume of double-distilled water. All extracts were passed through sodium sulfate (anhydrous; BioBasic) for dehydration, subjected to silica gel chromatography, and eluted with 100% hexane. The color fractions were then dried under nitrogen gas and resuspended with 0.5 ml of acetone. After centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 20 min), extracts were filtered (0.45-μm-pore-size GHP membrane; Pall) to remove fine particles.

Analysis of carotenoids.

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis was performed for the initial analysis under a 100% hexane solvent system (17). For oxygenated carotenes, a acetone-hexane (40:60) solvent system was used. A total of 20 μl of the collected color fractions were applied to a Zorbax eclipse XDB-C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm; Agilent Technologies) and typically eluted under isocratic conditions with a solvent system containing 80% acetonitrile, 15% methanol, and 5% isopropanol at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1 using an Agilent 1200 high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) system equipped with a photodiode array detector. For the elution of oxygenated carotenes, the mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile-H2O (90:10) for 20 min, followed by a gradient to acetonitrile-methanol-isopropanol (80:15:5) at 50 min. For structural elucidation, carotenoids were identified using a combination of HPLC retention times, absorption spectra, and mass fragmentation spectra. Mass fragmentation spectra were monitored in a mass range of m/z 200 to 800 on a liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS; Waters) equipped with an electron spray ionization (ESI) interface.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Functional assembly of B. linens lycopene and β-carotene synthetic modules in E. coli.

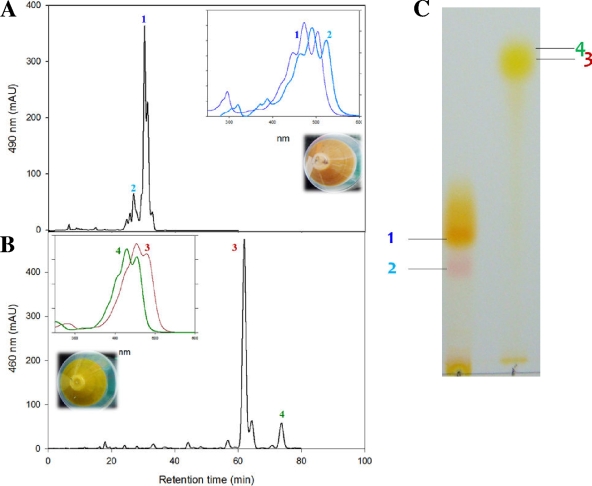

When plasmid pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL was transformed into E. coli cells, the transformants turned reddish, indicating successful formation of reddish lycopene in vivo. When crude carotenoid extracts of the reddish cells were analyzed by TLC and HPLC, another small peak in addition to lycopene was detected in the HPLC chromatogram (Fig. 2 A). This new peak corresponded to the reddish spot on the TLC plate (Fig. 2C). Based on its polarity, UV/Vis absorption property (λmax = 460, 491, and 523 nm) and relative molecular mass (M+ at m/z = 534.69), the new carotenoid was identified as 3,4-didehydrolycopene, which has 13 conjugated double bonds (CDB) in its backbone. The ratio of 3,4-didehydrolycopene to lycopene was 1:5.6 based on the peak area calculated by using Agilent ChemStation software. Formation of 3,4-didehydrolycopene was further confirmed by complementing two dissected lycopene pathway modules. All E. coli cells with a combination of pACM-EBL-BBL + pUCM-IBL, pACM-BBL-IBL + pUCM-EBL, or pACM-EBL-IBL + pUCM-BBL produced 3,4-didehydrolycopene, as did E. coli (pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL) (data not shown). These results indicate that 3,4-didehydrolycopene is one of the end products of the reconstructed B. linens lycopene pathway.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of recombinant E. coli cells engineered with reconstructed B. linens carotenoid biosynthetic pathways. HPLC analyses of crude extracts of E. coli(pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL) (A) and E. coli(pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL) (B) were carried out, as well as TLC analysis (C). The following carotenoids were identified: peak 1, lycopene (λmax = 447, 473, and 503; [M+H]+ at m/z = 537.75); peak 2, 3,4-didehydrolycopene (λmax = 460, 491, and 523; M+ at m/z = 534.69); peak 3, β-carotene (λmax = 427, 453, and 481; M+ at m/z = 536.86); peak 4, 7,8-dihydro-β-carotene (λmax = 403, 429, and 453; M+ at m/z = 539). Insets show the recorded absorption spectra for individual peaks and pelleted cells of recombinant E. coli.

The bacterial phytoene desaturase CrtI introduces CDBs into colorless phytoene to neurosporene (9 CDBs), lycopene (11 CDBs), or 3,4-didehydrolycopene (13 CDBs) with three-, four-, or five-step desaturation reactions, respectively (25). Wild-type five-step-desaturase CrtI, which is capable of producing 3,4-didehydrolycopene, is very rare in nature, whereas four-step -desaturase CrtI, which is capable of producing lycopene, such as Pantoea-derived CrtI, and three-step-desaturase CrtI, which is capable of producing neurosporene, such as Rhodobacter-derived CrtI or Staphylococcus-derived CrtN, are common in nature (18). It is known that fungi Neurospora crassa phytoene desaturase Al-1 has the ability to catalyze the stepwise introduction of up to five double bonds into phytoene and produce 3,4-didehydrolycopene, which is further transformed into torulene (11). Formation of the rare 3,4-didehydrolycopene was also reported as an intermediate in an in vitro evolved 3,4,3′,4′-tetradehydrolycopene pathway utilizing the mutant Pantoea CrtI14 even though 3,4-didehydrolycopene was not directly detected (27). Interestingly, purified Pantoea CrtI could produce a small amount of fully conjugated 3,4,3′,4′-tetradehydrolycopene under certain in vitro conditions (8). The major carotenoids synthesized in B. linens are isorenieratene and its hydroxy compounds, which came from lycopene containing 11 CDBs in its backbone (12, 15). However, in a heterologous E. coli, B. linens CrtI introduces 13 CDBs in phytoene unlike the original host strain B. linens (15). This result suggests that heterologously expressed B. linens CrtI may show altered activity than expected. This has been previously suggested, however, until now, there has only been limited experimental data supporting this hypothesis.

TLC, HPLC, and LC/MS analysis of the crude extracts of β-carotene producing E. coli(pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL) were performed. As expected, β-carotene (λmax = 427, 453, and 481 nm; M+ at m/z = 536.69) was the dominant compound, and there was no accumulation of lycopene (Fig. 2B), indicating that four heterologously expressed enzymes—CrtE, CrtB, CrtI, and CrtYcYd—were functionally assembled in E. coli. Interestingly, in addition to the main peak corresponding to β-carotene, a small peak was also detected in the HPLC chromatogram, corresponding to a compound that was lighter yellow than β-carotene on the TLC plate (Fig. 2C). This compound (λmax = 403, 429, and 453 nm; [M+H]+ m/z = 539) was found to be 7,8-dihydro-β-carotene, which is a neurosporene-derivative that contains a β-ionone ring at both ends (Fig. 1). CrtY from P. ananatis and LCY from the plant Capsicum annuum are reported to be able to produce 7,8-dihydro-β-carotene from neurosporene (29). Unlike common lycopene cyclase, heterodimeric B. linens CrtYcYd consisting of two genes, crtYc and crtYd, showed low amino acid sequence homology with other lycopene cyclases (16).

Extension of 3,4-didehydrolycopene pathway with a mutant lycopene cyclase CrtY2 and a spheroidene monooxygenase CrtA in E. coli.

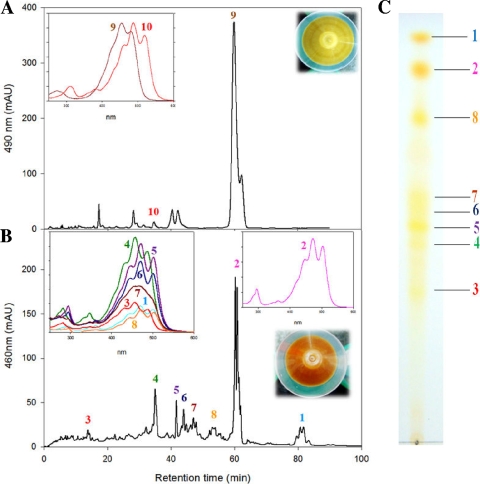

As shown in Fig. 2B, no 3,4-didehydrolycopene-derivative torulene was detected, indicating that 3,4-didehydrolycopene was not a substrate for wild-type B. linens lycopene cyclase CrtYcYd. Thus, the engineered 3,4-didehydrolycopene synthetic pathway was extended by incorporating the mutant Pantoea lycopene cyclase CrtY2 in E. coli. The mutant Pantoea CrtY2 was generated by in vitro evolution and used to produce torulene in 3,4,3′,4′-tetradehydrolycopene/lycopene-producing E. coli (27). Coexpression of mutant CrtY2 on pUC-CrtY2 in 3,4-didehydrolycopene/lycopene-producing E. coli(pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL) resulted in the formation of torulene (λmax = 460, 488, and 520 nm; [M+H]+ at m/z = 535.86) as a minor product and β-carotene as a major product (Fig. 3 A).

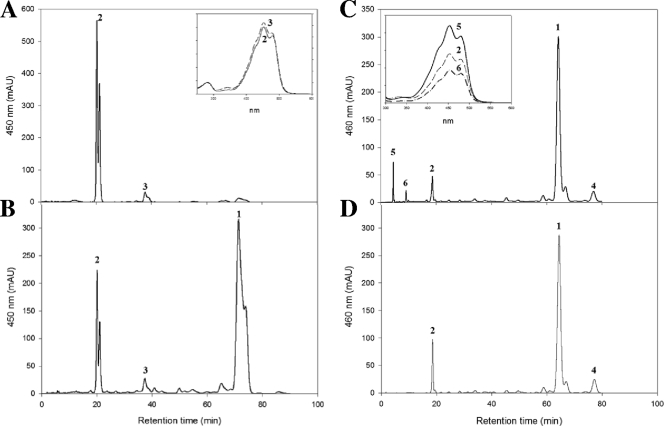

FIG. 3.

Analysis of extension of the reconstructed lycopene/3,4-didehydrolycopene pathway with a mutant CrtY2 or CrtARC. HPLC analysis of the reconstructed lycopene/didehydrolycopene pathway with a mutant lycopene cyclase CrtY2 (A) and a spheroidene monooxygenase CrtARC (B) in E. coli was carried out, as well as TLC (C). The following carotenoids were identified: peak 1, lycopene (λmax = 447, 473, and 503; [M+H]+ at m/z = 537.75); peak 2, 1,2-dihydrolycopene-2-one (λmax = 443, 469, and 500; [M+H]+ at m/z = 553.74); peak 9, β-carotene (λmax = 427, 453, and 481; M+ at m/z = 536.86); peak 10, torulene (λmax = 460, 488, and 520 nm; [M+H]+ at m/z = 535.86); peaks 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 were unidentified polar carotenoids. Insets show the recorded absorption spectra for individual peaks and pelleted cells of recombinant E. coli.

The spheroidene monooxygenase CrtA from Rhodobacter strains had been known to catalyze the asymmetrical introduction of one keto-group at the C2 position of spheroidene (2) and CrtA from Rubrivivax gelatinosus known to produce symmetrical 2,2′-diketospirilloxanthin (14). However, our recent study showed that CrtA is more promiscuous and able to introduce one or two keto-groups into acyclic carotenoid structures such as lycopene and 3,4,3′,4′-tetradehydrolycopene (17). However, extension of the wild-type or engineered 3,4-didehydrolycopene pathway has never been examined using CrtA. Therefore, the catalytic promiscuity of CrtA in the engineered 3,4-didehydrolycopene pathway in E. coli was examined. Coexpression of CrtA on pUCM-ARC in 3,4-didehydrolycopene/lycopene-accumulating E. coli(pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL) produced acyclic xanthophylls 1,2-dihydrolycopene-2-one (λmax = 443, 469, and 500 nm; [M+H]+ at m/z = 553.74) (16) as a main product and several polar compounds (Fig. 3B). The minor polar compounds had a very similar UV/Vis absorption spectra to lycopene and neurosporene (see insets in Fig. 3B), indicating that they may be oxolycopene or neurosporene derivatives. However, this could not be conclusively verified because only low amounts of the compounds were observed in the cell extracts, which made the structural analysis difficult. A similar profiling pattern was observed in our previous study (17), where extension of the 3,4,3′,4′-tetradehydrolycopene/lycopene pathway with CrtA produced 1,2-dihydrolycopene-2-one and phillipsiaxanthin, which is a dihydroxy-diketo derivative of 3,4,3′,4′-tetradehydrolycopene, as main products.

Extension of B. linens β-carotene synthetic module in E. coli.

P. ananatis carotene hydroxylase CrtZ was used for directed extension of the engineered B. linens β-carotene pathway in E. coli. When P. ananatis CrtZPAN was coexpressed in E. coli(pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL), hydroxylated β-carotene zeaxanthin (λmax = 424, 453, and 480; [M+H]+ at m/z = 569.8) was produced without the accumulation of β-carotene (Fig. 4 A). It has been reported that most P450 monooxygenases are not active in prokaryotes, but CYP175A1 (P450 monooxygenase) from Thermus thermophilus was shown to be functional in E. coli, and this enzyme introduced hydroxyl groups into the β-ionone rings of β-carotene, producing zeaxanthin (4).

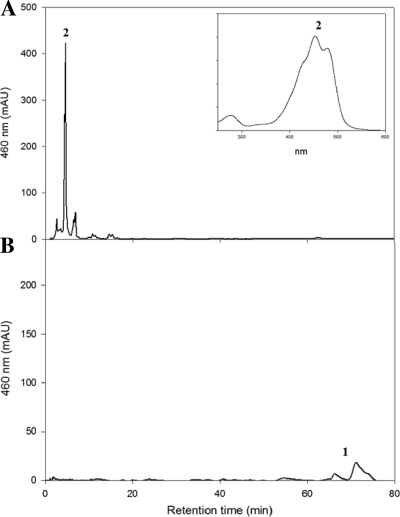

FIG. 4.

Functional analysis of cytochrome P450 in E. coli cells producing β-carotene. Carotenoid profiles of β-carotene-producing recombinant E. coli cells expressing the background plasmid pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL with pUCM-ZPAN (A) and pUCM-P450 (B) are shown. The following carotenoids were identified: peak 1, β-carotene (λmax = 427, 453, and 481; M+ at m/z = 536.69); and peak 2, zeaxanthin (λmax = 424, 453, and 480; [M+H]+ at m/z = 569.8). The inset shows the recorded absorption spectra for individual peaks.

B. linens was reported to have a P450-dependent cytochrome monooxygenase, which catalyzes the hydroxylation of aromatic rings of isorenieratene, resulting in 3-hydroxyisorenieratene and 3,3′-dihydroxyisorenieratene (6). We therefore examined whether B. linens P450 monooxygenase was active on a non-natural substrate β-carotene in heterologous E. coli. When B. linens P450 monooxygenase was constitutively expressed on pUCM-P450BL in E. coli(pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL), hydroxylated β-carotene zeaxanthin was not detected (Fig. 4B), indicating that B. linens P450 monooxygenase could not use β-carotene as a substrate. It might be due to the lack of a cofactor. We then examined whether B. linens P450 monooxygenase could use a natural substrate isorenieratene to produce hydroxy isorenieratene in a heterologous E. coli.

To test this, the reconstructed β-carotene pathway was further extended by coexpressing B. linens carotene desaturase CrtU on pUCM-UBL in E. coli(pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL). CrtU is known to desaturate β-ionone rings of β-carotene and simultaneously transfer a methyl group to form an aryl carotenoid, isorenieratene, in B. linens. As expected, β-carotene produced in E. coli was converted to isorenieratene (λmax = 427, 453, and 481 nm; M+ at m/z = 528.91) as the major product and a small amount of a β-isorenieratene-like compound (λmax = 427, 453, and 481 nm) was also produced (Fig. 5 A). Next, the isorenieratene synthetic pathway was further extended by exploiting the B. linens P450 monooxygenase to generate 3-hydroxyisorenieratene and 3,3′-dihydroxyisorenieratene. When P450 monooxygenase and CrtU on pUCM-UBL-P450BL were simultaneously coexpressed in β-carotene-producing E. coli(pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL), isorenieratene and β-isorenieratene-like compounds were produced in addition to a large amount of β-carotene (Fig. 5B). Incomplete conversion of β-carotene into isorenieratene indicates that P450 monooxygenase expression negatively affected the function of CrtU or decoupled the optimal coordination of CrtU with other carotenogenic enzymes. To reduce the metabolic burden caused by the high level of expression of P450 monooxygenase and CrtU, the inducible lac promoter-containing pUC19 was used instead of the constitutive lac promoter-containing pUCM. Without induction, the expression of carotenogenic enzymes on pUC19 is enough to produce carotenoids in E. coli.

FIG. 5.

HPLC analysis of β-carotene and its derivatives produced by engineered E. coli. HPLC analysis of reconstructed β-carotene and its derivative pathways in E. coli(pUCM-UBL) (A), E. coli(pUCM-UBL-P450) (B), E. coli(pUC19-UBL-ZPAN) (C), or E. coli(pUC19-UBL-P450) (D) was performed. The following carotenoids were identified: peak 1, β-carotene (λmax = 427, 453, and 481; M+ at m/z = 536.69); peak 2, isorenieratene (λmax = 427, 453, and 481; M+ at m/z = 528.91); peak 3, β-isorenieratene (λmax = 427, 453, and 481); peak 4, 7,8-dihydro-β-carotene (λmax = 403, 429, and 453; [M+H]+ at m/z = 539); peak 5, zeaxanthin (λmax = 424, 453, and 480; [M+H]+ at m/z = 569.8); and peak 6, agelaxanthin A (λmax = 424, 453, and 480; [M+H]+ at m/z = 548.77). Insets show the recorded absorption spectra for individual peaks.

When P450 monooxygenase and CrtU on pUC19-UBL-P450BL was simultaneously coexpressed without induction in β-carotene-producing E. coli(pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL), isorenieratene was produced as a major product, accumulating a large amount of β-carotene (Fig. 5C). The carotenoid profile observed in pUC19-UBL-P450BL + pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL was similar to the profile observed in pUCM-UBL-P450BL + pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL. Next, active CrtZPAN was coexpressed instead of P450 monooxygenase with CrtU because P450 monooxygenase appeared to be inactive in E. coli. When CrtZPAN and CrtU on pUC19-UBL-ZPAN were simultaneously coexpressed without induction in β-carotene-producing E. coli(pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL), zeaxanthin, isorenieratene, and a new compound were detected with the accumulation of β-carotene (Fig. 5D). The new compound was identified as agelaxanthin A (λmax = 427, 453, and 481 nm; M+ at m/z = 548.77), which has one aromatic ring and a hydroxy group in the β-ionone ring (Fig. 1). One of the most interesting results was the formation of agelaxanthin A because it is a very rare structure with asymmetric ends (28) and is primarily present in marine sponges (9). The asymmetric structure of agelaxanthin A could be generated by a sequential or simultaneous reaction of CrtU and CrtZPAN in E. coli(pUC19-UBL-ZPAN + pACM-EBL-BBL-IBL-YBL). If agelaxanthin A was generated by a simultaneous reaction between both CrtU and CrtZPAN, CrtU and CrtZPAN would have to recognize less than half molecule of β-carotene, and then hold one end of β-carotene at the active site of each enzyme until the reaction was finished. In the case of a sequential reaction for agelaxanthin A generation, CrtU or CrtZPAN would have to form functional multimers and release its intermediate compound, for example, β-isorenieratene for CrtU or β-cryptoxanthin for CrtZPAN, from the active site of each enzyme and take up a non-natural intermediate compound, for example, β-isorenieratene for CrtZPAN. Although these are a probable mechanism, it is very difficult to conclusively know the reaction sequence for agelaxanthin A. However, agelaxanthin A formation using CrtU and CrtZPAN demonstrates that combinatorial biosynthesis can generate asymmetric carotenoid structures that are hardly accessible without directed evolution.

In conclusion, the present study showed for the first time that the B. linen lycopene, β-carotene, and isorenieratene pathways were functionally expressed in a synthetic module in E. coli. Interestingly, B. linen phytoene desaturase (CrtI) unexpectedly produced 3,4-didehydrolycopene in addition to lycopene in E. coli. Using the combinatorial biosynthesis, 7,8-dihydro-β-carotene, torulene and asymmetric dicyclic carotenoid agelaxanthin A were obtained. These results demonstrate that reconstruction of biosynthetic pathways and extension with promiscuous enzymes in a heterologous host holds promise as a powerful strategy for generating structurally diverse compounds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea grants funded by the Korean Government (2009-0071135 and NRF-2009-C1AAA001-2009-0093062). This study was also supported by the Priority Research Centers Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (2009-0093826) and by an Ajou University research fellowship of 2009.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 June 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrecht, M., S. Takaichi, S. Steiger, Z. Y. Wang, and G. Sandmann. 2000. Novel hydroxycarotenoids with improved antioxidative properties produced by gene combination in Escherichia coli. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:843-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong, G. A., M. Alberti, F. Leach, and J. E. Hearst. 1989. Nucleotide sequence, organization, and nature of the protein products of the carotenoid biosynthesis gene cluster of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol. Gen. Genet. 216:254-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong, G. A., and J. E. Hearst. 1996. Genetics and molecular biology of carotenoid pigment biosynthesis. FASEB J. 10:228-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blasco, F., I. Kauffmann, and R. D. Schmid. 2004. CYP175A1 from Thermus thermophilus HB27, the first β-carotene hydroxylase of the P450 superfamily. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 64:671-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Boer, A. L., and C. Schmidt-Dannert. 2003. Recent efforts in engineering microbial cells to produce new chemical compounds. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 7:273-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dufosse, L., and M. C. De Echanove. 2005. The last step in the biosynthesis of aryl carotenoids in the cheese ripening bacteria Brevibacterium linens ATCC 9175 (Brevibacterium aurantiacum sp. nov.) involves a cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase. Food Res. Int. 38:967-973. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dufosse, L., P. Mabon, and A. Binet. 2001. Assessment of the coloring strength of Brevibacterium linens strains: spectrocolorimetry versus total carotenoid extraction/quantification. J. Dairy Sci. 84:354-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraser, P. D., N. Misawa, H. Linden, S. Yamano, K. Kobayashi, and G. Sandmann. 1992. Expression in Escherichia coli, purification, and reactivation of the recombinant Erwinia uredovora phytoene desaturase. J. Biol. Chem. 267:19891-19895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garson, M. J., V. Partali, S. e. Liaaen-Jensen, and I. L. Stoilov. 1988. Isoprenoid biosynthesis in a marine sponge of the Amphimedon genus: incorporation studies with [1-14C]acetate, [4-14C]cholesterol, and [2-14C]mevalonate. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 91:293-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyomarc'h, F., A. Binet, and L. Dufosse. 2000. Production of carotenoids by Brevibacterium linens: variation among strains, kinetic aspects and HPLC profiles. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24:64-70. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hausmann, A., and G. Sandmann. 2000. A single five-step desaturase is involved in the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway to beta-carotene and torulene in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 30:147-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh, L. K., T. C. Lee, C. O. Chichester, and K. L. Simpson. 1974. Biosynthesis of carotenoids in Brevibacterium sp. KY 4313. J. Bacteriol. 118:385-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson, E., and W. Schroeder. 1995. Microbial Carotenoids. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 53:119-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakitani, Y., R. Fujii, Y. Hayakawa, M. Kurahashi, Y. Koyama, J. Harada, and K. Shimada. 2007. Selective binding of carotenoids with a shorter conjugated chain to the LH2 antenna complex and those with a longer conjugated chain to the reaction center from Rubrivivax gelatinosus. Biochemistry 46:7302-7313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohl, W., H. Achenbach, and H. Reichenbach. 1983. The pigments of Brevibacterium linens: aromatic carotenoids. Phytochemistry 22:207-210. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krubasik, P., and G. Sandmann. 2000. A carotenogenic gene cluster from Brevibacterium linens with novel lycopene cyclase genes involved in the synthesis of aromatic carotenoids. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263:423-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, P. C., A. Z. R. Momen, B. N. Mijts, and C. Schmidt-Dannert. 2003. Biosynthesis of structurally novel carotenoids in Escherichia coli. Chem. Biol. 10:453-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, P. C., and C. Schmidt-Dannert. 2002. Metabolic engineering toward biotechnological production of carotenoids in microorganisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 60:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee, P. C., Y. G. Yoon, and C. Schmidt-Dannert. 2009. Investigation of cellular targeting of carotenoid pathway enzymes in Pichia pastoris. J. Biotechnol. 140:227-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, P. C., C. Salomon, B. Mijts, and C. Schmidt-Dannert. 2008. Biosynthesis of ubiquinone compounds with conjugated prenyl side chains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:6908-6917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mijts, B. N., P. C. Lee, and C. Schmidt-Dannert. 2005. Identification of a carotenoid oxygenase synthesizing acyclic xanthophylls: combinatorial biosynthesis and directed evolution. Chem. Biol. 12:453-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mijts, B. N., P. C. Lee, and C. Schmidt-Dannert. 2004. Engineering carotenoid biosynthetic pathways. Methods Enzymol. 388:315-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romero, P. A., and F. H. Arnold. 2009. Exploring protein fitness landscapes by directed evolution. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:866-876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandmann, G. 2002. Combinatorial biosynthesis of carotenoids in a heterologous host: a powerful approach for the biosynthesis of novel structures. Chembiochem 3:629-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandmann, G. 2009. Evolution of carotene desaturation: the complication of a simple pathway. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 483:169-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt-Dannert, C., P. C. Lee, and B. N. Mijts. 2006. Creating carotenoid diversity in Escherichia coli cells using combinatorial and directed evolution strategies. Phytochem. Rev. 5:67-74. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt-Dannert, C., D. Umeno, and F. H. Arnold. 2000. Molecular breeding of carotenoid biosynthetic pathways. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:750-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimada, A., Y. Ezaki, J. Inanaga, T. Katsuki, and M. Yamaguchi. 1981. Partial synthesis of aromatic carotenoids, tedanin, agelaxanthin a, tethyatene, and renieratene. Tetrahedron Lett. 22:773-774. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takaichi, S., G. Sandmann, G. Schnurr, Y. Satomi, A. Suzuki, and N. Misawa. 1996. The carotenoid 7,8-dihydro-Ψ end group can be cyclized by the lycopene cyclases from the bacterium Erwinia uredovora and the higher plant Capsicum annuum. Eur. J. Biochem. 241:291-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tao, L., S. Picataggio, P. E. Rouvière, and Q. Cheng. 2004. Asymmetrically acting lycopene β-cyclases (CrtLm) from non-photosynthetic bacteria. Mol. Genet. Genomics 271:180-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tao, L., H. Yao, and Q. Cheng. 2007. Genes from a Dietzia sp. for synthesis of C40 and C50 β-cyclic carotenoids. Gene 386:90-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tobias, A. V., and F. H. Arnold. 2006. Biosynthesis of novel carotenoid families based on unnatural carbon backbones: a model for diversification of natural. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids. 1761:235-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Umeno, D., and F. H. Arnold. 2004. Evolution of a pathway to novel long-chain carotenoids. J. Bacteriol. 186:1531-1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umeno, D., A. V. Tobias, and F. H. Arnold. 2005. Diversifying carotenoid biosynthetic pathways by directed evolution. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69:51-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ye, R. W., H. Yao, K. Stead, T. Wang, L. Tao, Q. Cheng, P. L. Sharpe, W. Suh, E. Nagel, D. Arcilla, D. Dragotta, and E. S. Miller. 2007. Construction of the astaxanthin biosynthetic pathway in a methanotrophic bacterium Methylomonas sp. strain 16a. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 34:289-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.