Abstract

Surface samples of the 2007 Microcystis bloom occurring in Copco Reservoir on the Klamath River in Northern California were analyzed genetically by sequencing clone libraries made with amplicons at three loci: the internal transcribed spacer of the rRNA operon (ITS), cpcBA, and mcyA. Samples were taken between June and October, during which time two cell count peaks occurred, in mid-July and early September. The ITS and cpcBA loci could be classified into four or five allele groups, which provided a convenient means for describing the Microcystis population and its changes over time. Each group was numerically dominated by a single, highly represented sequence. Other members of each group varied by changes at 1 to 3 nucleotide positions, while groups were separated by up to 30 nucleotide differences. As deduced by a partial sampling of the clone libraries, there were marked population turnovers during the season, indicated by changes in allele composition at both the ITS and cpcBA loci. Different ITS and cpcBA genotypes appeared to be dominant at the two population peaks. Toxicity (amount of microcystin per cell) and toxigenic potential (mcyB copy number) were lower during the second peak, and the mcyB copy number fell further as the bloom declined.

Toxic freshwater cyanobacterial blooms, commonly caused by Microcystis, are of current concern in many parts of the world because of their effects on drinking water, water-based recreation, and watershed ecology (5, 7). Microcystis cells are able to produce microcystin, a nonribosomally synthesized cyclic heptapeptide hepatotoxin with potent inhibitory activity against mammalian protein phosphatases (27) whose synthesis is directed by the 55-kb mcy gene cluster (25). The Microcystis genus exhibits worldwide occurrence, although the extent of genetic differentiation between or within geographical regions is currently uncertain due to a relatively sparse database, in spite of a growing number of studies (1, 2, 9, 11, 26, 28, 29).

Only a few studies to date have used gene-specific tools to investigate the changes in the Microcystis population structure throughout the development of a bloom season. In some instances, there has been little indication of major population changes. Thus, the proportion of toxigenic (mcyB+) Microcystis was stable over the course of two consecutive bloom seasons in Lake Wannsee (Berlin, Germany) (17). The internal transcribed spacer of the rRNA operon (ITS) genotype, as assessed by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and sequencing, was also stable in Lake Volkerak (Netherlands) during 2001 (15). In contrast, studies of other lakes have observed changes in the Microcystis genotypes and in the proportion of potentially toxigenic cells during a bloom season (3, 15, 21, 31, 32). A better understanding of the population changes that occur during the development of toxic blooms is important in understanding their ecology and in assessing whether it might be feasible to manage Microcystis blooms in order to minimize toxicity.

Copco Reservoir is a lake formed by a hydroelectric dam on the Klamath River in northern California. Beginning in 2004, highly toxic blooms dominated by Microcystis have developed between June and November (10, 13). Most studies of Microcystis blooms have been conducted in lakes with low in- and outflows. Copco Reservoir sits on a major river with normal through-flows of 1,000 to 3,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) during bloom season, although much of this flow occurs below the epilimnion, resulting in a surface water residence time of 20 to 25 days during summer (13). The consequences of toxic blooms in the reservoir may be carried to downstream reaches of the river, since elevated Microcystis levels have been present downstream of Copco Reservoir (14). We report here the results of a survey of the genotypic structure of the Microcystis population in Copco Reservoir during the 2007 bloom season. Major population shifts evident at the ITS and cpcBA loci coincided with the replacement of toxigenic with nontoxigenic strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and DNA extraction.

Water samples (250 ml), including floating scum, were collected as surface grabs by the Department of Natural Resources of the Karuk Tribe of Northern California from site CR01 in Copco Reservoir. CR01 is situated at a water depth of about 25 m near the dam at 41.982° latitude, −122.328° longitude, river mile 198.6. At one date (13 June 2007), the sample was taken from the nearby shore (CRCC, Copco Cove ramp).

One sample collected from the top 3.5 m of the water column at site MDT (42.385° latitude, −121.927° longitude) of Upper Klamath Lake (UKL) (18), 55 miles upstream of Copco Reservoir (provided by the U.S. Geological Survey [USGS]), was included in the analysis. UKL is a shallow, well-mixed lake (90% of the lake is less than 4 m deep) that experiences persistent summer blooms of nontoxic Aphanizomenon flos-aquae; low levels of toxic Microcystis are commonly present.

Samples from both lakes were provided to us as splits from ongoing water quality-monitoring programs at Copco Reservoir and Upper Klamath Lake. Water quality data from both sites and all sampling dates are available at Karuk Tribe (http://karuk.us/dnr/documentation.php) and USGS (http://or.water.usgs.gov/projs_dir/klamath_ltmon/) websites. Samples were shipped to the laboratory on ice and processed within 4 days of collection. Five to 25 ml of sample was filtered onto glass-fiber disks (Whatman GF/C) stacked on 0.2-μm Supor membrane filters (Pall) and frozen until extraction. The glass-fiber filters were used in all subsequent DNA extractions, and the 0.2-μm filters were archived. No green coloration was detected on the 0.2-μm filters for any of the samples analyzed during this study. DNA was extracted as previously described (20). Briefly, frozen glass-fiber filters were ground and exposed to lysozyme (1 mg/ml), SDS (0.4%), and proteinase K (0.2 mg/ml) before double extraction with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol.

DNA analysis.

The ITS, cpcBA, and mcyA loci were PCR amplified with primers designed for cyanobacterial specificity, with products cloned for clone library analysis. The primers were ITS (481- to 491-bp amplicons), CS1F (GYCACGCCCGAAGTCRTTAC) and ULR (CCTCTGTGTGCCTAGGTATC) (12); cpcBA (623-bp amplicons), PCBF (GGCTGCTTGTTTACGCGACA) and PCAR (CCAGACCACCAGCAACTAA) (20); and mcyA (246- to 252-bp amplicons), mcyA-Cd1F (AAAATTAAAAGCCGTATCAAA) and mcyA-Cd1R (AAAAGTGTTTTATTAGCGGCTCAT) (8). All PCR mixtures were in 25 μl with a 1- to 10-ng DNA template, Platinum Taq high-fidelity buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM concentrations of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 200 nM concentrations of the forward and reverse primers, and 1.25 units Platinum Taq high-fidelity polymerase (Invitrogen). Reactions were conducted for 30 cycles with 56°C annealing and 68°C extension steps for 30 s each, with a final 5-min extension at 72°C. PCR products were detected by ethidium bromide staining after electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels.

Quantitative PCR targeting Microcystis-specific cpcBA and mcyB genes was conducted using primers and TaqMan probes as described previously (17). Reaction mixtures (25 μl) consisted of 12.5 μl of Maxima Probe qPCR master mix (Fermentas), 900 nM concentrations of each primer and 250 nM probe, and 5 ng of genomic DNA as the template. Cycle conditions were 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min, in an ABI 7500 real-time PCR machine. For each gene, a plasmid containing the target sequences amplified from Copco Reservoir Microcystis DNA was constructed. Dilutions of these plasmids and of DNA extracted from reference Microcystis aeruginosa cultures UTEX 2385 (microcystin producing) and UTEX 2386 (microcystin nonproducing) (UTEX Culture Collection of Algae) were used as standards. Dilutions of UTEX 2385 DNA were used to generate standard curves that were included in each run. All reactions were conducted in triplicate and in the linear response range.

The cpcBA, ITS, and mcyA amplicons were cloned using a pGEM kit from Promega and chemically competent Top10 One Shot Escherichia coli cells from Invitrogen. Selected colonies were screened by colony PCR using either the cpcBA or ITS primer pairs. Colonies that gave positive PCR products were grown overnight in 2× yeast tryptone (YT) plus carbenicillin to generate plasmid preparations (Purelink quick miniprep kit; Invitrogen). Insert DNA sequences were confirmed by two-way sequencing and submitted to GenBank.

Population diversity parameters were estimated with Arlequin v3.11 (nucleotide diversity) (6) and Fastgroup II (Shannon index) (33) set for 100% similarity. Rarefaction curves (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) showed that sampling was incomplete to various degrees, as is common for clone library analysis of multiple samples (23). Maximum parsimony network analysis was performed using the statistical parsimony program TCS v1.21 (4).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The insert DNA sequences were assigned GenBank accession numbers GU249152 to GU249302.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Transition from high to low toxicity during development of the Microcystis bloom during 2007.

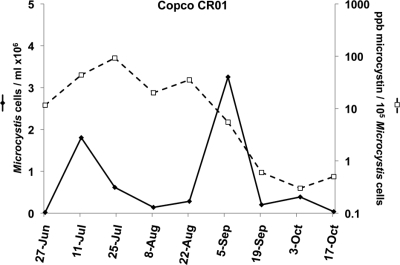

Surface samples were collected near the dam of Copco Reservoir throughout the 2007 bloom season, at CR01 from July through October, and at CRCC (Copco Cove boat ramp) on 27 June. Microscopic phycological analysis and microcystin toxin analyses (by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) were obtained by the Karuk Tribe (results summarized in reference 14). The cyanobacterial bloom was dominated by Microcystis at all times, with small appearances of Aphanizomenon and Anabaena. There were two peaks in Microcystis accumulation at CR01, an early peak measured on 11 July and a larger peak centered on the first week of September (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Progress of the Microcystis bloom in Copco Reservoir in 2007. Microcystis cell counts (⧫) and microcystin content (□) in surface samples taken at site CR01 at the indicated dates were assessed by microscopic phycological analysis and enumeration. Microcystin (extracellular plus intracellular) was determined by ELISA. Cell counts and toxin determinations were conducted with splits of the same samples, some of which were the same samples genetically analyzed in this study. Data were derived from reference 14.

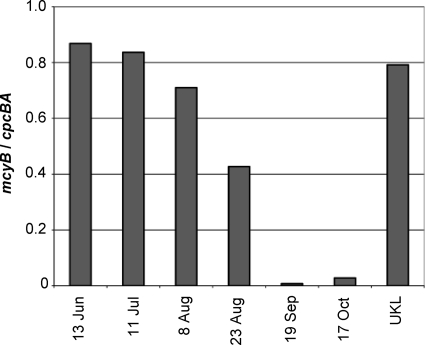

The reported amount of microcystin present per Microcystis cell fell over 100-fold at CR01 during the course of the bloom, with the greatest decline occurring in the period spanning the last week of August and the first half of September (Fig. 1). This coincided with the peak of the bloom. The decline in toxin per cell coincided with a decrease in the toxigenic potential of the Microcystis bloom, as measured by the ratio of mcyB to cpcBA gene copy number (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Loss of the mcyB gene during the 2007 bloom season in Copco Reservoir. Quantitative PCR was used to determine the relative copy numbers of the Microcystis-specific mcyB and cpcBA loci (average from three experiments). Samples were taken from Copco Reservoir at the indicated dates and from the MDT8 site in Upper Klamath Lake (UKL) on 21 August 2007.

Large-scale population turnover in Copco Reservoir indicated by analysis of the ITS alleles present.

Clone libraries representing cyanobacterial ITS amplicons were constructed for several time points to obtain a picture of the genetic makeup of the Microcystis population. One hundred fifty-five full-length sequences of the 481- to 491-bp Microcystis ITS sequence were obtained, among which were 61 different sequences. There were no matches to these sequences in the GenBank database.

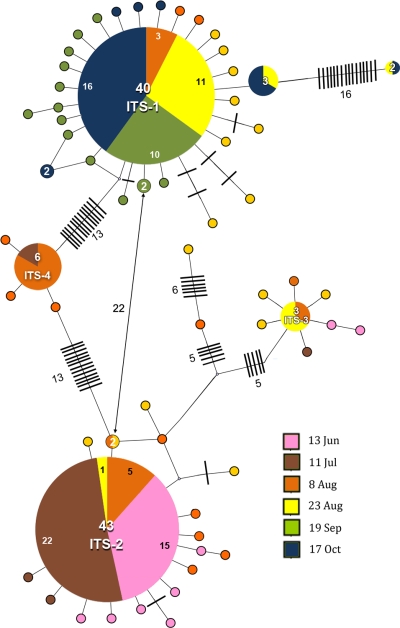

An initial phylogenetic analysis of the ITS sequences suggested classification into four sequence groups. This was confirmed by construction of a maximum parsimony network (Fig. 3), which also revealed the makeup of each sequence group and their relationships to each other. Groups 1 to 4 are dominated by abundant single sequences (termed most-abundant sequences [MAS]) with an array of rare closely related sequences differing from the MAS by 1 or, in a few cases, 2 or 3 nucleotides (Fig. 3). Groups 1 to 4 are well separated genetically, with between 9 and 30 nucleotide differences separating the MAS of each group. Only three sequences did not fit into the four groups. Classification of sequences into groups thus provides a convenient framework for analyzing the population changes occurring throughout the season.

FIG. 3.

Relationships between ITS genotypes collected from a 2007 Microcystis bloom in Copco Reservoir. The maximum parsimony network created with the TCS version 1.21 program (4) from all sequences generated from clone libraries made from the June through October samples separates the ITS sequences into four allele groups. The larger circles represent the MAS genotypes of each group, which are identified by name. The areas of circles are roughly proportional to the number of times a sequence was found, which is also indicated by the numbers entered within the larger circles. The number of nucleotide differences between two genotypes is the sum of steps on the shortest connecting path, summing crosshatches, intervening genotypes, and junction nodes (small circles). Sampling times are color coded as indicated in the legend. MAS GenBank accession numbers are as follows: ITS-1, GU249289; ITS-2, GU249253; ITS-3, GU249225; ITS-4, GU249216.

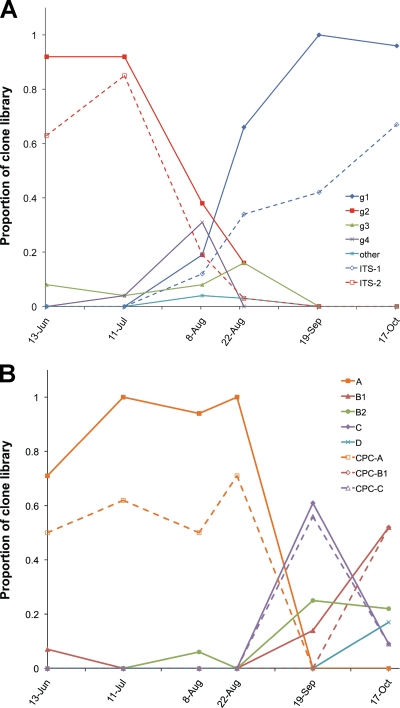

Genotype diversity statistics estimated from ITS clone libraries made from the samples from different time points (Table 1) indicate overall low diversity, with a diversity peak for the August samples. Maximum-parsimony networks for clone libraries made from each sample (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) confirm a simple predicted population structure, with more diversity present during August. Changes in the ITS alleles across the bloom season are shown in Fig. 4 A, which plots the relative contributions of ITS alleles from groups 1 to 4 for each time point. Group 2 sequences were predominant early, during June and July, with the group 2 MAS (ITS-2) accounting for up to 92% of the sequences analyzed. In contrast, group 1 sequences were predominant late in the season, during September and October (Fig. 4A), and a single sequence was again a large part of that population (up to 67% for ITS-1). The shift from predominantly group 2 sequences coincided with the decline of the early (June/July) bloom (Fig. 1), while the second bloom peak seemed to correspond to the ascendency of group 1 sequences, which persisted beyond the bloom decline in mid-September. High levels of toxicity (Fig. 1) and the presence of the mcyB gene (Fig. 2) were associated with the early, but not the late, peak. A variety of sequences was recovered in the August clone libraries, during the period between group 2 and group 1 dominance.

TABLE 1.

Diversity of clone libraries made from each sample

| Clone library and sample date | No. of clones | No. of genotypes | No. of clones of most-abundant genotype (MAS)a | Nucleotide diversityb | Shannon indexc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | |||||

| Copco | |||||

| 13 June | 24 | 10 | 15 (ITS-2) | 0.005 ± 0.003 | 1.27 |

| 11 July | 26 | 5 | 22 (ITS-2) | 0.004 ± 0.003 | 0.48 |

| 8 August | 26 | 13 | 5 (ITS-2) | 0.029 ± 0.015 | 2.22 |

| 5 (ITS-4) | |||||

| 23 August | 32 | 21 | 11 (ITS-1) | 0.031 ± 0.016 | 1.93 |

| 19 September | 23 | 14 | 10 (ITS-1) | 0.003 ± 0.002 | 0.70 |

| 17 October | 24 | 7 | 16 (ITS-1) | 0.005 ± 0.003 | 0.73 |

| UKL | |||||

| 21 August | 17 | 9 | 9 (ITS-2) | 0.053 ± 0.027 | 1.08 |

| cpcBA | |||||

| Copco | |||||

| 13 June | 14 | 7 | 7 (CPC-A) | 0.014 ± 0.007 | 0.90 |

| 11 July | 21 | 9 | 13 (CPC-A) | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 1.29 |

| 8 August | 16 | 9 | 8 (CPC-A) | 0.007 ± 0.004 | 1.12 |

| 23 August | 17 | 6 | 12 (CPC-A) | 0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.44 |

| 19 September | 17 | 15 | 4 (CPC-B2) | 0.014 ± 0.007 | 1.87 |

| 17 October | 23 | 6 | 12 (CPC-B1) | 0.022 ± 0.011 | 1.19 |

| UKL | |||||

| 21 August | 19 | 4 | 16 (CPC-A) | 0.013 ± 0.007 | 0.61 |

FIG. 4.

Changes in ITS and cpcBA allele populations during the 2007 bloom season in Copco Reservoir. (A) The relative abundances of the members of ITS sequence groups 1 to 4 are plotted across the bloom season; poorly clustered sequences GU249218 and GU249219 are represented as “other.” The June sample was from site CRCC, and all others were from CR01. The dashed lines report the relative abundances of the MAS genotypes belonging to groups 1 and 2 (ITS-1 and ITS-2, respectively). (B) The relative abundances of the members of cpcBA sequence groups A to D are plotted across the bloom season. The dashed lines report the relative abundances of the MAS genotypes belonging to groups A, B1, and C (CPC-A, CPC-B1, and CPC-C, respectively).

Different timing of population shifts suggested by analysis at the cpcBA locus.

A similar clone library analysis was conducted for cpcBA amplicons. One hundred thirty-two full-length sequences of the 623-bp Microcystis cpcBA amplicon were recovered, representing 46 different sequences. Several of these matched sequences that were recently reported from Copco Reservoir or its sister impoundment, Iron Gate Reservoir (19), and identical sequences were also present in GenBank from worldwide sources such as Spain, Japan, Israel, and Switzerland.

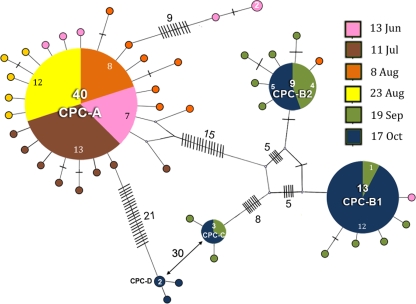

Analysis of the cpcBA locus generally paralleled the results from the ITS analysis, indicating an allele population similarly low in diversity (Table 1) and dominated by four sequence groups, A, B1, B2, and C, with a minor group, D (Fig. 5) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Only two sequences did not fit into these five groups. Identical cpcBA sequences recently reported from Copco Reservoir (19) belonged mostly to groups A, B2, and C. As deduced from the ITS analysis, large population shifts are also indicated from cpcBA analysis, but the timing is different (Fig. 4B). Group A sequences were predominant in clone libraries made from June through 23 August, after which time they were replaced by a mixture of sequences from the other groups. Because the mcyB copy number was very low in the September and October samples (Fig. 2), most of the group B1, B2, C, and D cpcBA alleles would be expected to derive from nontoxigenic Microcystis strains.

FIG. 5.

Relationships between cpcBA genotypes collected from a 2007 Microcystis bloom in Copco Reservoir. The maximum parsimony network created from all sequences generated from clone libraries made from June through October separates the cpcBA genotypes into five allele groups. Details are as in Fig. 3. MAS GenBank accession numbers are as follows: CPC-A, GU249203; CPC-B1, GU249162; CPC-B2, GU249171; CPC-C GU249154; CPC-D, GU249176.

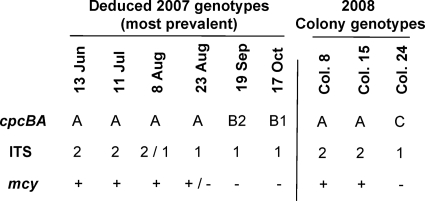

The major population switch indicated by cpcBA alleles thus occurred between 23 August and 19 September, and the period of greatest cpcBA diversity occurred during September and October (Fig. 4B). This contrasts with major shifts in ITS alleles between 11 July and late August, with apparent ITS diversity highest during August (Fig. 4A). Analysis of the two loci thus reveals population transitions that are more complex than indicated by either locus alone. Because of the dominance of certain allele groups in most samples, and incorporating our analyses of relative mcyB levels (Fig. 2), we can infer the predominant 3-locus genotypes (ITS/cpcBA/mcy) of Microcystis present at different sampling times in Copco Reservoir (Fig. 6). Most importantly, because the transition from the dominant early genotype occurred at different times for the ITS and cpcBA loci, there seem to be strains present in the Copco system that reflect recombination between these genes. Thus, cpcBA group A strains with either group 2 or group 1 ITS alleles seem to be present, and these are both probably mcy+. Similarly, it appears that ITS group 1 strains can have cpcBA group A, C, or B1 alleles; these may all be nontoxic, except perhaps the group A members (Fig. 6). Such complexities have not previously been revealed in Microcystis populations, which have usually been studied for a single locus outside the mcy gene cluster.

FIG. 6.

Microcystis genotypes in Copco Reservoir. The predicted genotypes at the three analyzed loci for most of the population at the 2007 sampling times are indicated at left. Mixed populations were present on 8 August and 23 August. The determined genotypes of three isolated colonies taken from Copco Reservoir on 15 July 2008 (colonies 8 and 15) or 5 August 2008 (colony 24) are given at right. The amplicon sequences derived from these colonies matched exactly the MAS of the indicated sequence groups.

Gene linkages such as those hypothesized in Fig. 6 must be verified by direct means, such as genetic analysis of single cells or clonal colonies (11). No colonies were isolated from the 2007 Copco Reservoir bloom, but three colonies from the 2008 bloom were shown to have cpcBA-A ITS-2 mcy+ and cpcBA-C ITS-1 mcy-negative genotypes (Fig. 6). These correspond to postulated genotypes that were prevalent during 2007. This type of colony analysis coupled with population analysis at more than one locus (such as cpcBA and ITS) is needed to obtain a full picture of the population dynamics of a bloom.

Transitions in Microcystis blooms from initial high toxicity to low toxicity have been observed previously, involving a variety of lake types (3, 15, 31, 32). Among these, the study by Briand et al. (3) of Grangent Reservoir, a major dam on a large river, is the case most closely resembling that of Copco Reservoir. On the other hand, bloom seasons without major changes in toxicity have been reported from other lakes (15, 17). More studies are necessary to determine the lake-specific and seasonal influences that govern such population changes.

Allele differentiation at the mcyA locus.

Clone libraries of mcyA amplicons were analyzed for the Copco Reservoir samples taken at three time points, 11 July, 23 August, and 19 September. About 10 amplicons were fully sequenced from each clone library, revealing seven different sequences. Sequence GU249297 was the most prevalent, found 10 times for 11 July and 5 times for 23 August. This sequence (and four other cloned sequences) encodes an McyA protein with Thr-Phe appearing between amino acids Lys-1610 and Ser-1611 of McyA encoded by M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 (GenBank accession number AM778952). mcyA genes with this Lys-Ser dipeptide were first reported from the Great Lakes (1, 22) and remain uncommon in the database. Our study and a recent report (19) show that this mcyA variant is common in the Klamath watershed, suggesting a wider distribution in the United States.

A single sequence found in the 23 August library encoded a Thr-Trp dipeptide at the above location of the McyA protein. Similar sequences were recently reported from Copco Reservoir (19) and from Florida (30).

A final distinct mcyA sequence lacked the additional dipeptide (as in M. aeruginosa PCC 7806; AF183408); this sequence was the most prevalent clone (found eight times) in the 19 September library. Four closely related sequences were also found, mostly during September 2007, in another study of Copco Reservoir (19).

The Upper Klamath Lake Microcystis population is closely related to the early season Copco population.

ITS, cpcBA, and mcyA amplicon clone libraries were analyzed for a single sample from Upper Klamath Lake (UKL) collected on 21 August 2007. Sequences identical to those found in Copco Reservoir dominated each library. Thus, ITS-2 was found in 9 of 17 clones (53%), group 2 was represented in 13 of 17 clones (76%), and group 1 and 3 sequences accounted for 2 of 19 clones (12%) each. In the cpcBA library, CPC-A was found in 12 of 19 clones (63%), and group A sequences accounted for 16 of 19 clones (84%). The remaining sequenced clones were 1 from group B2 and 2 related to group B1. Seven ITS and 5 cpcBA sequences not found in the Copco Reservoir libraries were recovered from UKL; all 8 mcyA clones sequenced were identical to the most-prevalent sequence found in the Copco Reservoir clone libraries (GU249297).

The sequence groups represented in the UKL sample suggested the presence of a bloom similar to the early bloom present in Copco Reservoir during June (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). This is the period when toxicity was high in Copco (Fig. 1), and a high mcyB-to-cpcBA gene copy ratio was indeed measured for the UKL sample (Fig. 2). The coexistence of several genotypes in UKL and Copco Reservoir, separated by about 80 river km, may not be surprising. However, the two lakes and their bloom characteristics are very different, a situation that a priori may be expected to favor different genotypes. UKL is a relatively high-altitude (1,260 m), large shallow lake that is dominated by annual nontoxic Aphanizomenon blooms, while Copco Reservoir is an impoundment on a major river situated at a lower altitude (800 m) and in a canyon, thereby exposing it to higher summer temperatures. A recent study of Microcystis blooms on a major river in France showed that blooms in different impoundments on the same river do not necessarily equilibrate (23). A major variable in whether blooms are transported to inoculate sites downstream of a reservoir may be the depth at which water is released relative to the location of the bloom in the water column (23).

Potential for genetic group-specific monitoring and population studies.

Description of the Microcystis population in terms of the small number of sequence groups that dominate the network maps of Fig. 3 and 5 has facilitated the recognition of the inferred population changes that may have occurred during 2007 (Fig. 4). It also offers the potential to develop nucleic acid probes for group-specific detection to aid in population monitoring. For pragmatic reasons, our study did not involve a complete sampling of clone libraries, but inclusion of sequences of the same cpcBA and mcyA amplicons from the 2007 Copco Reservoir bloom water samples collected in another recent study (19) supported our classification into discrete allele groups (not shown). Only a few sequences do not fall into the groups we have described in this study.

Previous authors have classified alleles present in Microcystis blooms into genotype groupings (3, 15, 24, 32). However, this is the first indication from two loci (ITS and cpcBA) that a Microcystis bloom is comprised of well-separated allele groups that are dominated by single genotypes. ITS analyses of Microcystis blooms on the Loire River (France) have also indicated a simple population structure (3, 23), suggesting that a simplified group-based description may be more generally applicable. Group-specific PCR or hybridization assays may provide a convenient and economical approach to the monitoring of Microcystis populations that provides valuable insight into population structure. Such an approach is widely used in other fields for single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping (16). This approach would likely need an initial inventory of the major allele groups present in a given study area and would also need to incorporate controls for detecting the emergence of novel sequences that fall outside the known allele groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Susan Corum of the Karuk Tribe of California in collecting Copco Reservoir samples and of Mary Lindenberg and Tamara Wood of the U.S. Geological Survey in collecting the UKL sample. We thank Andrea McHugh for assisting in the laboratory and Joe Eilers and Richard Raymond for discussions.

This work was supported by Oregon Sea Grant award NA060AR4170010.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 June 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allender, C. J., G. R. LeCleir, J. M. Rinta-Kanto, R. L. Small, M. F. Satchwell, G. L. Boyer, and S. W. Wilhelm. 2009. Identifying the source of unknown microcystin genes and predicting microcystin variants by comparing genes within uncultured cyanobacterial cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:3598-3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bittencourt-Oliveira, M. C., M. C. Oliveira, and C. J. S. Bolch. 2001. Genetic variability of Brazilian strains of the Microcystis aeruginosa complex (Cyanobacteria/Cyanophyceae) using the phycocyanin intergenic spacer and flanking regions (cpcBA). J. Phycol. 37:810-818. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briand, E., N. Escoffier, C. Straub, M. Sabart, C. Quiblier, and J. F. Humbert. 2009. Spatiotemporal changes in the genetic diversity of a bloom-forming Microcystis aeruginosa (cyanobacteria) population. ISME J. 3:419-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clement, M., D. Posada, and K. A. Crandall. 2000. TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol. Ecol. 9:1657-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dittmann, E., and C. Wiegand. 2006. Cyanobacterial toxins—occurrence, biosynthesis and impact on human affairs. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 50:7-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Excoffier, L., G. Laval, and S. Schneider. 2005. Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Bioinform. Online 1:47-50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falconer, I. R. (ed.). 2005. Cyanobacterial toxins of drinking water supplies: cylindrospermopsins and microcystins. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 8.Hisbergues, M., G. Christiansen, L. Rouhiainen, K. Sivonen, and T. Borner. 2003. PCR-based identification of microcystin-producing genotypes of different cyanobacterial genera. Arch. Microbiol. 180:402-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humbert, J. F., D. Duris-Latour, B. L. Berre, H. Giraudet, and M. J. Salencon. 2005. Genetic diversity in Microcystis populations of a French storage reservoir assessed by sequencing of the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer. Microb. Ecol. 49:308-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacoby, J. M., and J. Kann. 2007. The occurrence and response to toxic cyanobacteria in the Pacific Northwest, North America. Lake Reserv. Manage. 23:123-143. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janse, I., W. E. Kardinaal, M. Meima, J. Fastner, P. M. Visser, and G. Zwart. 2004. Toxic and nontoxic Microcystis colonies in natural populations can be differentiated on the basis of rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3979-3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janse, I., M. Meima, W. E. Kardinaal, and G. Zwart. 2003. High-resolution differentiation of cyanobacteria by using rRNA-internal transcribed spacer denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6634-6643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kann, J., and E. Asarian. 2007. Nutrient budgets and phytoplankton trends in Iron Gate and Copco Reservoirs, California, May 2005-May 2006. Final technical report to the State Water Resources Control Board, Sacramento, CA. Karuk Tribe of California, Department of Natural Resources, Orleans, CA.

- 14.Kann, J., and S. Corum. 2009. Toxigenic Microcystis aeruginosa bloom dynamics and cell density/chlorophyll a relationships with microcystin toxin in the Klamath River, 2005-2008. Karuk Tribe Department of Natural Resources, Orleans, CA. http://www.klamathwaterquality.com/documents/2009/2008_Karuk_Toxic_Cyanobacteria_summary.pdf.

- 15.Kardinaal, W. E., I. Janse, M. Kamst-van Agterveld, M. Meima, J. Snoek, L. R. Mur, J. Huisman, G. Zwart, and P. M. Visser. 2007. Microcystis genotype succession in relation to microcystin concentrations in freshwater lakes. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 48:1-12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim, S., and A. Misra. 2007. SNP genotyping: technologies and biomedical applications. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 9:289-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurmayer, R., and T. Kutzenberger. 2003. Application of real-time PCR for quantification of microcystin genotypes in a population of the toxic cyanobacterium Microcystis sp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6723-6730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindenberg, M. K., G. Hoilman, and T. M. Wood. 2009. Water quality conditions in Upper Klamath and Agency Lakes, Oregon, 2006. U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2008-5201. U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA.

- 19.Moisander, P. H., P. W. Lehman, M. Ochiai, and S. Corum. 2009. Diversity of Microcystis aeruginosa in the Klamath River and San Francisco Bay delta, California, U.S.A. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 57:19-31. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neilan, B. A. 2001. Genomic polymorphisms and the diversity of oxygenic phototrophs, p. 75-90. In P. A. Rochelle (ed.), Environmental molecular microbiology: protocols and applications. Horizon Scientific Press, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 21.Rinta-Kanto, J. M., E. A. Konopko, J. M. DeBruyn, R. A. Bourbonniere, G. L. Boyer, and S. W. Wilhelm. 2009. Lake Erie Microcystis: relationship between microcystin production, dynamics of genotypes and environmental parameters in a large lake. Harmful Algae 8:665-673. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rinta-Kanto, J. M., and S. W. Wilhelm. 2006. Diversity of microcystin-producing cyanobacteria in spatially isolated regions of Lake Erie. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5083-5085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabart, M., D. Pobel, D. Latour, J. Robin, M. J. Salencon, and J. F. Humbert. 2009. Spatiotemporal changes in the genetic diversity in French bloom-forming populations of the toxic cyanobacterium, Microcystis aeruginosa. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1:263-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanabe, Y., F. Kasai, and M. M. Watanabe. 2009. Fine-scale spatial and temporal genetic differentiation of water bloom-forming cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa: revealed by multilocus sequence typing. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1:575-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tillett, D., E. Dittmann, M. Erhard, H. von Dohren, T. Borner, and B. A. Neilan. 2000. Structural organization of microcystin biosynthesis in Microcystis aeruginosa PCC7806: an integrated peptide-polyketide synthetase system. Chem. Biol. 7:753-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tillett, D., D. L. Parker, and B. A. Neilan. 2001. Detection of toxigenicity by a probe for the microcystin synthetase A gene (mcyA) of the cyanobacterial genus Microcystis: comparison of toxicities with 16S rRNA and phycocyanin operon (phycocyanin intergenic spacer) phylogenies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2810-2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Apeldoorn, M. E., H. P. van Egmond, G. J. Speijers, and G. J. Bakker. 2007. Toxins of cyanobacteria. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 51:7-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vareli, K., G. Pilidis, M.-C. Mavrogiorgou, E. Briasoulis, and I. Sainis. 2009. Molecular characterization of cyanobacterial diversity and yearly fluctuations of microcystin loads in a suburban Mediterranean lake (Lake Pamvotis, Greece). J. Environ. Monit. 11:1506-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye, W., X. Liu, J. Tan, D. Li, and H. Yang. 2008. Diversity and dynamics of microcystin-producing cyanobacteria in China's third largest lake, Lake Taihu. Harmful Algae 8:637-644. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yilmaz, M., E. J. Phlips, and D. Tillett. 2009. Improved methods for the isolation of cyanobacterial DNA from environmental samples. J. Phycol. 45:517-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida, M., T. Yoshida, Y. Takashima, N. Hosoda, and S. Hiroishi. 2007. Dynamics of microcystin-producing and non-microcystin-producing Microcystis populations is correlated with nitrate concentration in a Japanese lake. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 266:49-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshida, M., T. Yoshida, Y. Takashima, R. Kondo, and S. Hiroishi. 2005. Genetic diversity of the toxic cyanobacterium Microcystis in Lake Mikata. Environ. Toxicol. 20:229-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu, Y., M. Breitbart, P. McNairnie, and F. Rohwer. 2006. FastGroupII: a web-based bioinformatics platform for analyses of large 16S rDNA libraries. BMC Bioinformatics 7:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.