Abstract

Grapevine fanleaf virus (GFLV) and Arabis mosaic virus (ArMV) from the genus Nepovirus, family Secoviridae, cause a severe degeneration of grapevines. GFLV and ArMV have a bipartite RNA genome and are transmitted specifically by the ectoparasitic nematodes Xiphinema index and Xiphinema diversicaudatum, respectively. The transmission specificity of both viruses maps to their respective RNA2-encoded coat protein (CP). To further delineate the GFLV CP determinants of transmission specificity, three-dimensional (3D) homology structure models of virions and CP subunits were constructed based on the crystal structure of Tobacco ringspot virus, the type member of the genus Nepovirus. The 3D models were examined to predict amino acids that are exposed at the external virion surface, highly conserved among GFLV isolates but divergent between GFLV and ArMV. Five short amino acid stretches that matched these topographical and sequence conservation criteria were selected and substituted in single and multiple combinations by their ArMV counterparts in a GFLV RNA2 cDNA clone. Among the 21 chimeric RNA2 molecules engineered, transcripts of only three of them induced systemic plant infection in the presence of GFLV RNA1. Nematode transmission assays of the three viable recombinant viruses showed that swapping a stretch of (i) 11 residues in the βB-βC loop near the icosahedral 3-fold axis abolished transmission by X. index but was insufficient to restore transmission by X. diversicaudatum and (ii) 7 residues in the βE-αB loop did not interfere with transmission by the two Xiphinema species. This study provides new insights into GFLV CP determinants of nematode transmission.

The transmission of a virus from one plant to another is a key step in the virus life cycle. For a majority of plant viruses, transmission is dependent upon vectors, mostly arthropods, soil-inhabiting nematodes, and plasmodiophorids (13, 15). A successful transmission depends on the competency of the vector to acquire virions, bind them to specific retention sites, and release them in a recipient plant. Virus transmission by a vector is often characterized by some degree of specificity; it can be broad or narrow, but it is a prominent feature for numerous plant viruses and their vectors (2). The viral determinants engaged in vector transmission involve the coat protein (CP) that either binds directly to vector ligands or associates with nonstructural viral proteins, like a helper component (HC), to create a molecular bridge between virions and the vector (25, 44). For both strategies, only a very limited number of amino acids on either the CP or the HC contribute to the transmission process and to vector specificity.

For the aphid-transmitted Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV; genus Cucumovirus, family Cucumoviridae), the CP is the sole viral determinant of transmission (10, 12), and a negatively charged loop of eight residues located on the surface of virions is directly involved in vector interactions (19, 26). For potyviruses such as Tobacco vein mottling virus (TVMV), the CP and HC are both involved in transmission by aphids. The amino acid motifs DAG located near the N terminus of the CP, KITC located near the N terminus of the HC-Pro, and PTK located into the central part of the HC-Pro are essential for transmission (35). For Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV; genus Caulimovirus, family Caulimoviridae), a single amino acid change in protein P2, which acts as HC, is sufficient to abolish aphid transmission (24). In the case of nematode-transmitted viruses, a single mutation in the HC protein 2b of Pea early-browning virus (PEBV; genus Tobravirus, unassigned family) is sufficient to prevent transmission (38). Similarly, a 15-amino-acid deletion at the C terminus of the CP abolishes transmission of PEBV (22). For members of the genus Nepovirus in the family Secoviridae, little information is available on viral determinants that govern nematode transmission (21). Transmission assays of pseudorecombinants between Raspberry ringspot virus (RpRSV) and Tobacco black ring virus (TBRV) showed the involvement of RNA2-encoded proteins and suggested a role of the CP in transmission specificity (reviewed in reference 3). Based on sequence alignments, the residue in position 219 of the RpRSV CP was proposed to be exposed at the surface of particles and involved in nematode transmission (33). However, no experimental evidence is available to confirm these hypotheses. Thus, our knowledge of the viral determinants of nepovirus transmission is rather scarce.

Grapevine fanleaf virus (GFLV) and Arabis mosaic virus (ArMV), two closely related species of the genus Nepovirus, family Secoviridae (31, 32), are responsible for a severe degeneration of grapevines that occurs in most vineyards worldwide (3). GFLV and ArMV have a bipartite RNA genome and share a similar genome organization, as well as a relatively high level of sequence similarity (39). The RNA1 of both viruses encodes replication and protein maturation functions, and the RNA2 encodes a protein involved in RNA2 replication, which is referred to as a homing protein (2AHP), the movement protein (2BMP) and the coat protein (2CCP) (3; see also Fig. 4). The nematode transmission of GFLV and ArMV illustrates the type of extreme specificity that can exist between vectors and viruses (8). GFLV is transmitted exclusively by Xiphinema index and ArMV is transmitted specifically by X. diversicaudatum. The transmission specificity of GFLV (4) and ArMV (23) maps to their respective 2CCP, but no information is available on 2CCP residues involved in vector interactions.

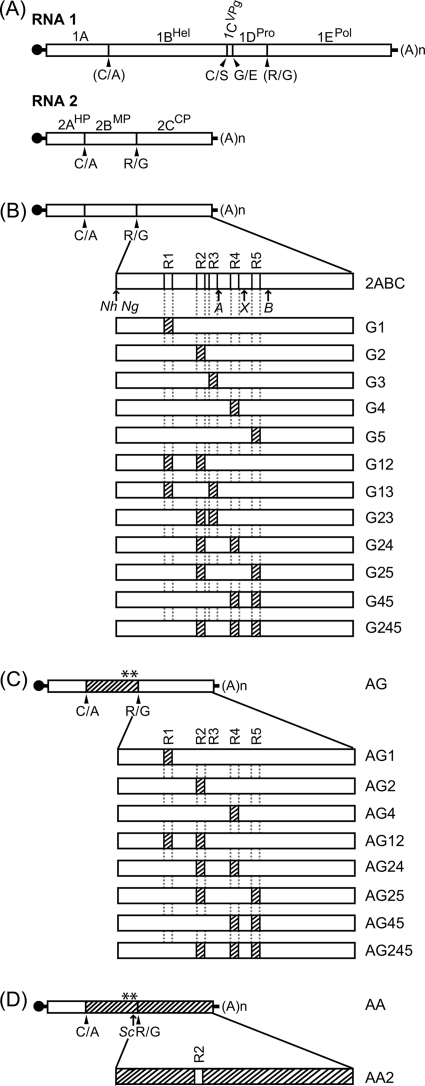

FIG. 4.

Schematic representation of GFLV chimeric RNA2 used in the present study. (A) Genetic organization of GFLV-F13 RNA1 and RNA2. Open boxes indicate open reading frames. The 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions are denoted by a single line, and the VPg is represented by a black circle. Arrowheads point out the polyprotein cleavage sites. Dipeptides shown in parentheses were suggested based on sequence analysis but have not been demonstrated experimentally. The name of the processed proteins is given on top of the boxes: Hel, putative helicase; VPg, viral protein genome linked; Pro, protease; Pol, polymerase; HP, putative homing protein; MP, movement protein; and CP, coat protein. (B to D) Chimeric RNA2 molecules generated by swapping regions R1 to R5 between GFLV and ArMV in a full GFLV RNA2 genetic background (B); in a partial GFLV RNA2 genetic background for which protein 2BMP is of ArMV origin, except amino acids 343 and 347 (−6 and −2 upstream of the R/G cleavage site between proteins 2BMP and 2CCP), which are of GFLV origin (asterisks above protein 2BMP) (C); or in a partial GFLV RNA2 genetic background, where proteins 2CCP and 2BMP are of ArMV origin, except amino acids 343 and 347 (D). Hatched boxes designate ArMV sequences. Restriction sites used for cloning are positioned with arrows: Nh, NheI (nt 2050 to 2055); Ng, NgoMIV (nt 2054 to 2059); A, Acc65I (nt 2678 to 2683); X, XmaI (nt 2852 to 2857); B, BglII (nt 3055 to 3060); and Sc, SacI (nt 2023 to 2028).

The main objective of our study was to delineate 2CCP amino acids involved in GFLV transmission by X. index and advance our knowledge of molecular features of nepovirus transmission. Three-dimensional (3D) homology-based models of GFLV virions and CP subunits were constructed by using the 3.5-Å crystal structure of Tobacco ringspot virus (TRSV) as a template (9). TRSV is the type member of the genus Nepovirus to which GFLV and ArMV belong (32) and is transmitted by the nematode X. americanum. From our structural models, residues predicted to be exposed at the external capsid surface, highly conserved among GFLV isolates but divergent between GFLV and ArMV isolates, were identified and selected for a reverse-genetics approach to determine their involvement in vector transmission. Our results indicate that a stretch of 11 residues predicted in the βB-βC loop of the CP B domain is essential for X. index-mediated transmission of GFLV. To our knowledge, this represents the first description of structural amino acids essential for nepovirus transmission by nematodes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus strains.

GFLV strain F13 (41) and ArMV strain S (16) were isolated from naturally infected grapevines and propagated in Chenopodium quinoa, a systemic host for both viruses. The sequence of the two genomic RNAs of both virus strains is determined (20, 28, 34; C. Ritzenthaler et al., unpublished). Full-length cDNA clones of GFLV-F13 RNA1 (plasmid pMV13) and RNA2 (plasmid pVec2ABC) are available for in vitro synthesis of transcripts (40). ArMV-S was used as a control in nematode transmission assays, and a cDNA of ArMV-S RNA2-U (20) was used in mutagenesis experiments.

GFLV 3D structure model building.

A protein/protein BLAST (1) search for potential structural templates was conducted using the query GFLV-F13 CP sequence (GI 25013721, 504 amino acids) against sequences available in the Protein Data Bank. CLUSTAL X (36) alignment was restricted to GFLV-F13, ArMV-S (GI 757527, 505 amino acids) and TRSV (GI 3913279; 513 amino acids) sequences. The structure described in TRSV 1A6C was used as a template for GFLV model building using MODELLER (30). Alignment was then refined by hand to accommodate structural constraints revealed by the 3D model. Putative surface residues of GFLV were considered to be those that aligned with the surface residues identified for TRSV by Chandrasekar and Johnson (9). Hexamers were built rather than isolated monomers because virus capsids are highly constrained by high symmetry, extensive contacts between monomers, and the fact that approximately one-third of the total accessible surface residues are predictably buried by direct neighbors.

The GFLV CP amino acid stretches presumably involved in transmission by X. index were identified by combining information from the GFLV capsid 3D model, the surface residues identified by Chandrasekar and Johnson (9), and the alignment of 219 GFLV and 20 ArMV CP sequences (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Sequences were aligned with AlignX (Vector NTI).

Development of chimeric GFLV RNA2.

Plasmid pVec2ABC carrying a full-length cDNA copy of GFLV-F13 RNA2 was used as a template to develop chimeric 2CCP genes (6). For cloning purposes, an Acc65I restriction site was introduced into pVec2ABC from positions 2678 to 2683 (nucleotide positions are given according to the GFLV-F13 RNA2 sequence, GenBank accession no. NC_003623) by site-directed PCR-mediated mutagenesis. The plasmid generated was named pVecAcc65I2ABC. Introducing Acc65I modified the nucleotide but not the amino acid composition of the wild-type GFLV-F13 2CCP.

Previous work showed that functional GFLV/ArMV RNA2 recombinants can be produced, providing a functional interaction between proteins 2BMP and 2CCP is maintained for cell-to-cell movement (5, 6). Mutations affecting regions R1 (nucleotides [nt] 2284 to 2302), R2 (nt 2609 to 2640), R4 (nt 2819 to 2842), and R5 (nt 2937 to 2965) of the GFLV 2CCP gene were produced by primer overlap extension mutagenesis (14), using the primers described in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The mutation affecting region R3 (nt 2666 to 2677) only required one PCR step because of the presence of the Acc65I restriction site into the reverse primer. Each PCR was carried out as described previously (4), except that the annealing time was reduced to 45 s at 60°C and the elongation time was adapted to the size of the PCR products. DNA amplicons obtained by PCR were digested with appropriate restriction enzymes (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and cloned into the corresponding sites in pVecAcc65I2ABC to yield pVecAcc65I2ABCG1, pVecAcc65I2ABCG2, pVecAcc65I2ABCG3, pVecAcc65I2ABCG4, and pVecAcc65I2ABCG5 (a “G” as a subscript indicates the GFLV origin of the 2CCP, and 1 to 5 indicate the mutated regions R1 to R5, respectively). For simplicity, transcripts and recombinant viruses derived from this series of constructs are referred to as G1, G2, G3, G4, and G5.

To produce mutants carrying combinations of regions R1, R2, and R3, chimeric plasmids pVecAcc65I2ABCG1 and pVecAcc65I2ABCG2 were used as the matrix for a second primer overlap—or single—PCR mutagenesis, and the resulting PCR fragments were cloned into pVecAcc65I2ABC, using NgoMIV and Acc65I to produce pVecAcc65I2ABCG12, pVecAcc65I2ABCG13 and pVecAcc65I2ABC23 (12, 13, and 23 as subscripts indicate the combination of the mutated regions 1 and 2, 1 and 3, and 2 and 3, respectively). For simplicity, transcripts and recombinant viruses derived from this second series of constructs are referred to as G12, G13, and G23.

To produce mutants carrying further combinations of swapped regions, mutant plasmids pVecAcc65I2ABCG1, pVecAcc65I2ABCG2, pVecAcc65I2ABCG3, pVecAcc65I2ABCG4, and pVecAcc65I2ABCG5 were digested with appropriate restriction enzymes (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), and restriction fragments containing the mutated region(s) were cloned sequentially into plasmids encoding a GFLV 2CCP gene already carrying a mutation (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). For simplicity, transcripts and recombinant viruses derived from this third series of constructs are referred to as G24, G25, G45, and G245.

Plasmid pVec2ABU-4-9C was engineered earlier (4) from pVec2ABU9C (6) to produce chimeric RNA2 constructs for which gene 2CCP is of GFLV origin and gene 2BMP is of ArMV origin, except amino acids in positions −2 and −6 upstream of the R/G cleavage site that remain of GFLV origin (4) in order to maintain a functional interaction between proteins 2BMP and 2CCP for systemic plant infection (6). Plasmid pVec2ABU-4-9C was renamed in the present study as pVec2ABACG (an “A” as a subscript indicates the chimeric nature of protein 2BMP). The complete CP coding sequence of G1, G2, G4, G12, G24, G25, G45, and G245 was cloned into plasmid pVec2ABACG by using the appropriate restriction enzymes (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) to produce pVec2ABACG1, pVec2ABACG2, pVec2ABACG4, pVec2ABACG12, pVec2ABACG24, pVec2ABACG25, pVec2ABACG45, and pVec2ABACG245, respectively. For simplicity, transcripts and recombinant viruses derived from this third series of constructs are referred to as AG1, AG2, AG4, AG12, AG24, AG25, AG45, and AG245.

Plasmid pVec2ABU-6CU (4) was used in the present study to introduce CP gene region R2 of GFLV origin in an ArMV CP gene and renamed as pVec2ABACA (an “A” as a subscript indicates the chimeric nature of protein 2BMP and the ArMV nature of protein 2CCP). Mutagenesis of CP region R2 and cloning into pVec2ABACA to yield pVec2ABACA2 was performed as described in Table S1 in the supplemental material. For simplicity, transcripts derived from this construct are referred to as AA2.

The integrity of the 21 GFLV chimeric RNA2 clones produced for the present study was verified by DNA sequencing.

In vitro transcription of GFLV cDNA clones and mechanical inoculation of plants.

GFLV RNA1 and RNA2, as well as GFLV chimeric RNA2, were obtained by in vitro transcription (6) and were mechanically inoculated into C. quinoa. Recombinant viruses were propagated in Nicotiana benthamiana by using crude sap of infected C. quinoa leaves as inoculum. Virus infection was assessed in uninoculated apical leaves of test plants two to 3 weeks postinoculation by double-antibody sandwich (DAS)-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with γ-globulins specific to GFLV and ArMV (42). Samples were considered positive if their optical densities at 405 nm (OD405s) were at least three times those of healthy controls after 120 min of substrate hydrolysis.

Functionality of GFLV chimeric RNA2 in Chenopodium quinoa protoplasts.

The functionality of chimeric RNA2 transcripts was evaluated by transfecting C. quinoa protoplasts in the presence of GFLV RNA1 transcripts. Viral RNA replication and encapsidation were assessed by RNase protection experiments, as described previously (6), except that riboprobes used for Northern hybridization corresponded to nt 4623 to 5810 of RNA1 (5′ half of gene 1EPOL) and nt 233 to 1006 of RNA2 (gene 2AHP).

Nematode transmission tests.

Nematode transmission assays were performed with N. benthamiana for X. index (4) and C. quinoa for X. diversicaudatum (23). Transmission assays used a minimum of five to six plants and were performed at least twice, except for G1 and AG1, which were tested only once. Synthetic GFLV, i.e., RNA derived from pMV13 and pVecAcc65I2ABC, referred to as 2ABC, and wild-type ArMV-S were used as controls in transmission assays with X. index and X. diversicaudatum. The presence of GFLV and ArMV was assessed in leaves of source plants by DAS-ELISA (4, 23).

Detection of GFLV and ArMV in nematodes.

The presence of GFLV and ArMV was verified in nematodes by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) with a GFLV/ArMV consensus reverse primer EVAGR (5′-GGCAAGTGTGTCCAAAGGAC-3′) and a GFLV-specific forward primer GF (5′-ATGTGGAAGAGGACGGAAGT-3′) or an ArMV-specific forward primer AF (5′-GTTACATCGAGGAGGATG-3′) to amplify 860- and 849-bp specific fragments, respectively (11).

Characterization of GFLV chimeric 2CCP gene progeny.

The progeny of chimeric GFLV RNA2 was characterized in infected plants by immunocapture (IC)/RT-PCR (5, 6) with the primers 208 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and 398 (5′-TGGGARARYRTNGAGGAAC-3′) that allow complete sequencing of the CP open reading frame. Sequences were analyzed with ContigExpress (Vector NTI).

RESULTS

Construction of a GFLV homology-based 3D model and search for surface residues potentially involved in X. index transmission.

To identify GFLV 2CCP amino acids involved in the transmission by X. index, we hypothesized that candidate residues are likely exposed at the external surface of virions, which are different between GFLV and ArMV isolates but highly conserved among GFLV isolates. The latter criterion was not considered absolute because no information is available on nematode transmissibility of most of the 219 GFLV and 20 ArMV variants for which CP sequences are available in GenBank (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

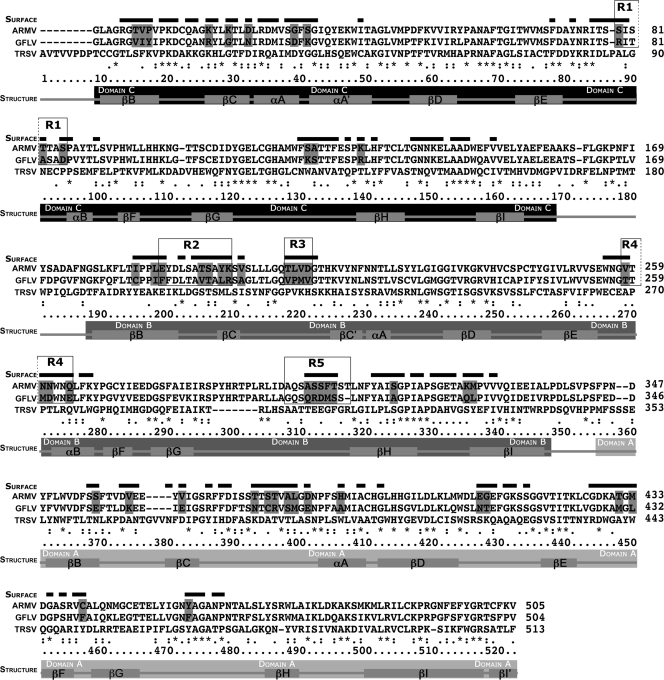

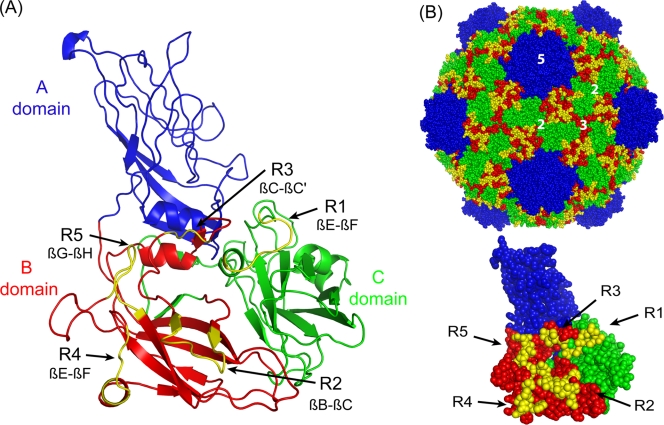

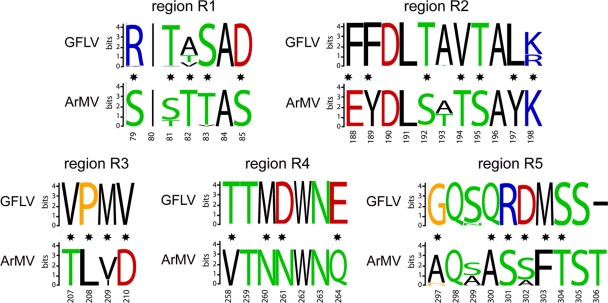

In the absence of a resolved structure for GFLV and ArMV, a 3D structural model of GFLV virions was constructed by examining Protein Data Bank for potential structural templates using the query GFLV-F13 CP sequence. The closest structural template to the GFLV CP was the CP of TRSV (PDB-ID: 1A6C) (9) with 25% sequence identity, 43% sequence similarity, and a score of 219 positive residues out of 513 for the crystal structure. CLUSTAL X alignments between GFLV-F13, ArMV-S, and TRSV were generated as indicated in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1). This alignment slightly differed from the one described previously (9). We considered putative surface residues of GFLV to be those that aligned with the surface residues identified for TRSV by Chandrasekar and Johnson (9). 3D homology models of GFLV virion and CP subunit constructed from the crystal structure of TRSV are presented in Fig. 2. The virion icosahedral lattice is of a pseudo T=3 symmetry and one CP consists of three trapezoid shaped β-barrel domains referred to as the C, B, and A domains from the N to the C termini, as shown previously for TRSV (9). Of the 156 nonconserved residues between GFLV-F13 and ArMV-S, 59 amino acids were predicted to be exposed at the external surface of the CP (highlighted in gray in Fig. 1), and nearly half of those (27 of the 59) clustered within the central B domain. Considering this high number of divergent surface residues, we restricted our reverse-genetics approach to areas with the highest concentration of divergent residues rather than to single isolated residues. Five regions (R1 to R5) ranging from 4 to 11 residues and displaying between 0 (region R3) and 57% (region R4) amino acid sequence identity between GFLV and ArMV were identified and selected for mutagenesis experiments (Fig. 3). The five candidate regions all located to predicted loops connecting β sheets within the B domain, except region R1 that mapped to the C domain (Fig. 1 and 2). The five CP regions were highly conserved within 219 GFLV or 20 ArMV variants (Fig. 3). When displayed in GFLV CP tertiary and quaternary structure models, the five regions mapped close together, with R1 closest to R3 and R2 closest to R5 (Fig. 2). The five regions surrounded a small depression between the 5-fold and 3-fold axes of the virion (Fig. 2). Importantly, no direct contact of the selected regions between the different subunits could be deduced from our 3D models, suggesting that the selected regions are unlikely to be involved in the CP-CP interactions necessary for virion assembly or stability.

FIG. 1.

Map of GFLV predicted surface residues potentially involved in X. index transmission. Refined CLUSTAL X alignment of the CP residues of TRSV (GI 3913279), GFLV-F13 (GI 25013721), and ArMV-S (GI 757527). The secondary structure of the TRSV atomic model is shown below the alignment. Surface residues of TRSV identified previously (9) are indicated by horizontal bars above the sequences. Predicted surface residues that are different between GFLV and ArMV are highlighted in gray. Boxes delineate regions 1 (R1), 2 (R2), 3 (R3), 4 (R4), and 5 (R5) used for inverse genetics studies because corresponding predicted surface residues are poorly conserved between GFLV and ArMV.

FIG. 2.

Homology-based model of GFLV and 2CCP regions targeted for mutagenesis. (A) Ribbon representation of the GFLV CP deduced from the TRSV crystal structure (PDB ID 1A6C). The predicted A, B, and C structural domains are indicated in blue, red, and green, respectively. The five regions selected for mutational analysis due to their predicted surface location and divergence between GFLV and ArMV appear in yellow. Regions R2, R3, R4, and R5 are located in loops in the B domain, whereas region R1 is located in the C domain βE-βF loop. (B) A space-filling model of GFLV particle quaternary structure viewed down the icosahedral 2-fold axis (top) and GFLV 2CCP subunit tertiary structure (bottom) showing the close proximity of regions R1 to R5. The icosahedral 5-fold, 3-fold, and 2-fold axes (labeled as 5, 3, and 2, respectively) are labeled for one icosahedral asymmetric unit (top). The figures were generated using PYMOL (www.pymol.org).

FIG. 3.

Logographical representations of the amino acid sequence conservation within CP regions R1 to R5 of GFLV and ArMV. The sequences of 219 GFLV and 20 ArMV variants (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were used to create a logographical representation. The different residues at each position in the GFLV CP amino acid sequences (top of each panel) and the ArMV CP amino acid sequences (bottom of each panel) are scaled according to their frequency. The CP amino acid positions are given on the x axis of each panel. Black stars indicate residues that differ between GFLV and ArMV. The black line at the end of GFLV region R5 (bottom right panel) represents a gap in the GFLV and ArMV 2CCP sequence alignment. Residues are colored according to their biochemical properties: positively charged in blue; negatively charged in red; hydrophobic in black; and polar uncharged in green and the proline, glycine, and cysteine in orange. CP sequence alignments were created by using AlignX (Vector NTI), and logo representations were obtained by using Weblogo (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi).

Engineering of recombinant viruses.

A reverse-genetics approach was used to investigate the involvement of GFLV candidate CP regions R1 to R5 in nematode transmission. Chimeric CP genes were obtained by substituting GFLV residues within regions R1 to R5 by their ArMV counterparts using site-directed mutagenesis of full-length infectious cDNA clones of GFLV RNA2 (40). Regions were substituted individually, in pairs or in triple combination (Fig. 4B). In addition, to circumvent possible defects in systemic movement of recombinant viruses in planta (5, 6), recombinants carrying single or combinations of ArMV CP regions R1 to R5 were also generated in an infectious cDNA clone of GFLV RNA2 for which the GFLV 2BMP gene was replaced by its ArMV counterpart (Fig. 4C), except for Leu343 (position −6 upstream of the R/G cleavage site between proteins 2BMP and 2CCP) and Val347 (position −2 upstream of the R/G cleavage site) of protein 2BMP that remained of GFLV origin to maintain infectivity (4, 6). Altogether, 21 CP recombinants were generated, 12 in a full GFLV RNA2 genetic background (Fig. 4B), eight in a partial GFLV RNA2 genetic background that included an ArMV protein 2BMP (Fig. 4C), and one in a partial GFLV RNA2 genetic background that included ArMV proteins 2BMP and 2CCP (Fig. 4D).

Infectivity assays of recombinant viruses in planta.

The infectivity of in vitro-synthesized GFLV RNA1 and chimeric RNA2 transcripts and the ability of the corresponding recombinant viruses to cause systemic plant infection is essential to obtaining infected plant roots for nematode transmission assays. Of the 21 GFLV recombinants tested, only recombinants G1, AG1, G2, and AG2 caused a systemic infection in planta with typical GFLV symptoms and DAS-ELISA-positive uninoculated apical leaves (Table 1). Recombinants exhibited a 2- to 5-day delay in symptom development compared to synthetic wild-type GFLV, i.e., 2ABC. However, this difference nearly vanished upon mechanical reinoculation of C. quinoa with crude sap from initially infected plant tissue, except for recombinant G2, which, for unknown reasons, remained recalcitrant to reinoculation in C. quinoa and N. benthamiana and was therefore omitted from further studies. Recombinant viruses G1, AG1, and AG2 were transferred successfully to N. benthamiana by mechanical inoculation, and the genetic stability and integrity of their RNA2 progeny was confirmed by IC/RT-PCR and sequencing of the CP gene. Importantly, neither reversion to wild-type GFLV sequences nor compensatory mutations in the 2CCP were ever observed.

TABLE 1.

Infectivity of chimeric RNA2 transcripts in the presence of GFLV RNA1

| Transcript | Plant infection |

Protoplast infection |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomsa | DAS-ELISAb | Replicationc | Encapsidationd | |

| 2ABC | + | + | + | + |

| G1 | + | + | + | + |

| G2 | +e | +e | + | + |

| G3 | - | - | + | - |

| G4 | - | - | + | + |

| G5 | - | - | + | - |

| G12 | - | - | + | - |

| G13 | - | - | + | NDf |

| G23 | - | - | + | - |

| G24 | - | - | + | - |

| G25 | - | - | + | - |

| G45 | - | - | + | - |

| G245 | - | - | + | - |

| AG | + | + | + | ND |

| AG1 | + | + | + | ND |

| AG2 | + | + | + | + |

| AG4 | - | - | + | + |

| AG12 | - | - | + | ND |

| AG24 | - | - | + | - |

| AG25 | - | - | + | - |

| AG45 | - | - | + | - |

| AG245 | - | - | + | - |

| AA | + | + | + | ND |

| AA2 | - | - | + | - |

Symptoms of mosaic, vein yellowing, and deformation were observed on apical leaves of C. quinoa after mechanical inoculation with transcripts of GFLV RNA1 and chimeric RNA2. +, Symptoms; -, no symptoms.

Plants tested positive (+) or negative (-) for viruses by DAS-ELISA in three independent experiments 15 days after mechanical inoculation of GFLV RNA1 and chimeric RNA2 transcripts. OD405 values of infected plants were 0.8 ± 0.2 compared to 0.07 ± 0.005 for healthy controls after 120 min of substrate hydrolysis. Positive plants for 2ABC had OD405 values of 1.5 ± 0.2 compared to 0.07 ± 0.005 for healthy controls after 120 min of substrate hydrolysis.

Replication was determined in C. quinoa protoplasts by Northern hybridization analysis after transfection with GFLV RNA1 and chimeric RNA2 transcripts.

Encapsidation was determined by Northern hybridization analysis after RNase protection assays on C. quinoa protoplasts transfected with GFLV RNA1 and chimeric RNA2.

Systemic infection was only observed in a few plants, and recombinant G2 could not be transferred from the initially infected C. quinoa to healthy C. quinoa or N. benthamiana by mechanical inoculation.

ND, not determined.

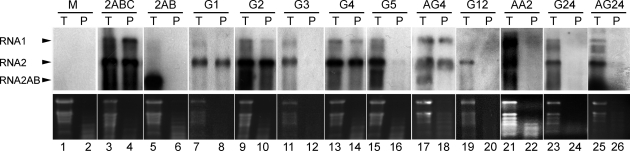

Effect of CP mutations on encapsidation.

The defect in in planta infectivity observed for most recombinant viruses engineered in the present study could result from deficiencies in replication, encapsidation, and/or cell-to-cell movement. To discriminate between these hypotheses, C. quinoa protoplasts were transfected with viral transcripts, and total RNA extracted 72 h posttransfection was analyzed by Northern hybridization using GFLV RNA1 and RNA2 riboprobes. The results showed that all chimeric RNAs were competent for replication (Table 1). After replication in protoplasts, the ability of chimeric protein 2CCP to encapsidate viral RNA was assessed under conditions that allows to distinguish RNase-protected, encapsidated viral RNA (P condition, PIPES buffer) from total, encapsidated, and nonencapsidated viral RNA (T condition, TLES buffer) as described previously (6). As expected, under T condition, progeny viral RNA was detected for all GFLV RNA1 and RNA2 combinations (Fig. 5 and Table 1), indicating that loss of infectivity was not due to replication. Under P condition, the only single recombinants in which progeny viral RNA could be detected were those affecting regions R1, R2, and R4, independently of the origin of the 2BMP gene (G1, G2, G4, AG2, and AG4, Fig. 5 and Table 1), indicating encapsidation of the corresponding viral genomic RNAs. In contrast, no viral RNA protection was observed for recombinants G3 and G5 as for mutant 2AB for which the CP gene is deleted (Fig. 5). RNase protection assays further indicated a deficiency in viral RNA encapsidation for all double or triple recombinants, including the ones combining regions that individually could be exchanged with no effect on encapsidation, i.e., G12, G24, and AG24 (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Finally, no protected RNA could be detected for recombinant AA2 (Fig. 5), showing that even if the ArMV region R2 could be placed in a GFLV 2CCP protein without effect on encapsidation (recombinant G2 and AG2), the reverse swapping was deleterious.

FIG. 5.

Northern blot analysis of viral RNA from transfected C. quinoa protoplasts. Total RNA was extracted to yield both encapsidated and nonencapsidated RNAs (lanes T with odd numbers) or RNase-protected RNAs (lanes P with even numbers). Protoplasts were transfected with transcripts of GFLV RNA1 and transcripts of RNA2: 2ABC (lanes 3 and 4); RNA2 deleted of the entire CP gene, 2AB (lanes 5 and 6); chimeric RNA2 with single region R1 to R5 of ArMV origin: G1 (lanes 7 and 8), G2 (lanes 9 and 10), G3 (lanes 11 and 12), G4 (lanes 13 and 14), G5 (lanes 15 and 16), and AG4 (lanes 17 and 18); chimeric RNA2 with combined substitutions of ArMV origin: G12 (lanes 19 and 20), G24 (lanes 23 and 24), and AG24 (lanes 25 and 26); or chimeric RNA2 with region R2 of GFLV origin in a ArMV 2CCP: AA2 (lanes 21 and 22). M, RNA extracted from mock-inoculated protoplasts (lanes 1 and 2). Viral RNAs were detected by using digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes complementary to GFLV genes 1EPol and 2AHP. The positions of GFLV RNAs indicated with arrowheads on the left (upper panel). (Lower panel) rRNA stained with ethidium bromide.

Effect of CP mutations on transmission by nematodes.

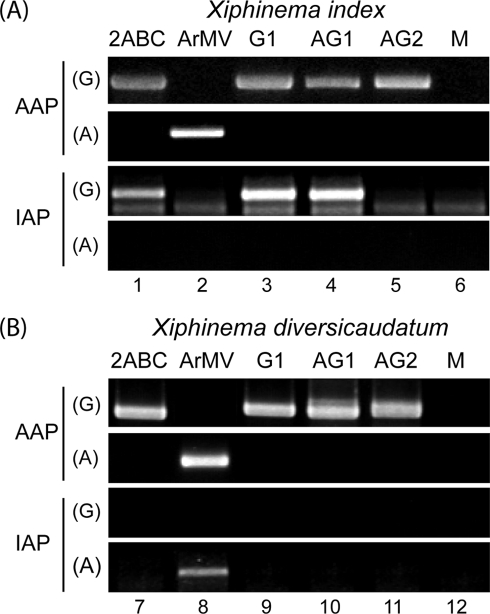

The transmissibility of recombinant viruses that induced systemic plant infection, i.e., G1, AG1, and AG2, by X. index and X. diversicaudatum was evaluated (4, 5). Recombinant AG2 was not transmitted by any of the two Xiphinema species, whereas recombinants G1 and AG1, like synthetic GFLV, were transmitted by X. index but not by X. diversicaudatum (Table 2). ArMV-S was the only virus transmitted by X. diversicaudatum (Table 2). Transmission rates varied between 67 and 100%, which is in complete agreement with previous reports on GFLV and ArMV transmission rates (4, 5). Such differences were statistically not sufficient to indicate possible variations in transmission efficiency between transmitted isolates. Analysis of the RNA2 progeny of recombinants G1 and AG1 in infected bait plants by IC/RT-PCR and sequencing indicated no change in nucleotide sequence relative to the corresponding cDNA clones, confirming the genetic stability of the recombinants. These results are consistent with the notion that CP region R2 is involved in GFLV transmission by X. index and CP region R1 is not essential for transmission specificity.

TABLE 2.

Transmissibility of GFLV recombinants by Xiphinema spp.

| Virus | Transmission (%)a by: |

|

|---|---|---|

| X. index | X. diversicaudatum | |

| 2ABC | 11/14 (79) | 0/23 (0) |

| ArMV-S | 0/30 (0) | 20/26 (77) |

| G1 | 6/9 (67) | 0/15 (0) |

| AG1 | 7/7 (100) | 0/15 (0) |

| AG2 | 0/20 (0) | 0/26 (0) |

| Healthy | 0/19 (0) | 0/14 (0) |

Transmission rates are given as the number of bait plants that reacted positively to GFLV or ArMV antibodies in DAS-ELISA over the total number of plants tested. A total of 200 nematodes were used per virus source plant.

Effect of CP mutations on virus acquisition and retention by nematodes.

The deficiency in nematode-mediated virus transmission could result from a lack of virus acquisition during the acquisition access period (AAP) or a failure of vectors to bind and release virus particles during the inoculation access period (IAP). To verify that nematodes fed on infected roots and ingested viruses, nematode specimens were randomly collected after the AAP and tested for virus presence by RT-PCR. Both vectors, X. index and X. diversicaudatum, ingested recombinants G1, AG1, AG2, synthetic GFLV, and wild-type ArMV independently of their transmission competency (Fig. 6). These results rule out the possibility that transmission failed due to a lack of virus acquisition by nematodes. Similarly, nematodes were tested for virus presence after the IAP to examine retention competency. Recombinants G1 and AG1 were detected in X. index, while recombinant AG2 was undetectable in the two nematode species (Fig. 6). In agreement with the specific transmission of GFLV and ArMV (5), synthetic GFLV was only detected in X. index and wild-type ArMV in X. diversicaudatum (Fig. 6). These RT-PCR results were consistent with our transmission data (Table 2) and confirmed that CP region R2 is required for GFLV retention in X. index, whereas CP region R1 does not seem essential for the specific virus retention by nematodes.

FIG. 6.

Virus detection in X. index and X. diversicaudatum at the end of the AAP and IAP. Thirty X. index (A) and X. diversicaudatum (B) specimens exposed to source plants infected with synthetic GFLV 2ABC (lanes 1 and 7), wild-type ArMV-S (lanes 2 and 8), recombinant G1 (lanes 3 and 9), recombinant AG1 (lanes 4 and 10), recombinant AG2 (lanes 5 and 11) or mock-inoculated plants (M, lanes 6 and 12) were randomly collected and tested by RT-PCR with (G) GFLV- or (A) ArMV-specific primers. DNA products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels.

In summary, CP region R2 is likely exposed at the external surface of virions where it functions as a determinant for GFLV transmission by X. index. Unfortunately, we were not able to test CP region R2 in the transmission of ArMV by X. diversicaudatum, due to defect in encapsidation of the reciprocal recombinant AA2 (Table 1, Fig. 5). The smaller CP gene region R1, which is probably also located at the external surface of particles, had no effect either on encapsidation or transmission of the virus.

DISCUSSION

Limited information is available on viral determinants responsible for nematode-mediated transmission of nepoviruses. Previous studies showed that the specific transmission of GFLV and ArMV by X. index and X. diversicaudatum, respectively, is determined by their respective CPs (4, 23). The identification of CP residues involved in transmission has been hampered by unsuccessful attempts at isolating natural GFLV or ArMV isolates that are deficient in nematode transmission and by a lack of resolved virion structure. In the present study, we investigated the contribution of five GFLV CP regions predicted at the external surface of virions in transmission by X. index following a reverse genetics approach based on the use of GFLV/ArMV chimeric RNA2 molecules. Our results were consistent with region 2 (2CCP amino acids 188 to 198) being essential for GFLV transmission by X. index. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on a CP domain involved in nepovirus transmission by nematodes.

The prediction of the five regions of interest at the surface of the virion was assisted by the construction of a homology based 3D model to minimize the loss of encapsidation that was previously limiting our mutational approach (6). This appeared to be partly successful as three regions (R1, R2, and R4) of the ArMV 2CCP could be inserted in the GFLV 2CCP without affecting encapsidation, showing that the model indeed was able to identify residues likely exposed at the surface of the virus. The usefulness of the model is further shown by the identification of two regions with a contact function; R2 involved in vector transmission and R4 possibly involved in cell-to-cell movement via 2CCP-2BMP interactions, as deduced from the absence of plant infection of the encapsidated mutants G4 and AG4. If confirmed, this would constitute the first hint in the identification of 2CCP residues involved in 2BMP-2CCP interactions for cell-to-cell movement of GFLV. However, the biological validation of our model is only partial since two regions (R3 and R5) could not be exchanged without affecting encapsidation. At this stage, we cannot rule out the possibility that CP function required for inter- or intrasubunit interactions or RNA encapsidation cannot be fulfilled by the ArMV derived amino acids or that our predicted structure of GFLV does not completely match the real structure. To overcome these uncertainties, the crystallographic structure of GFLV would be needed, although it might not be sufficient to unravel transmission determinants, because, by analogy with other icosahedral plant viruses, the dynamics of virus-vector interactions could depend on conformational changes (17, 29).

The defect in encapsidation of some recombinant GFLV variants was not associated with the size of the substituted 2CCP region or the degree of amino acid divergence. Indeed, recombinants carrying a mutated CP region R3 with only four residues were deficient in encapsidation, whereas recombinants affecting CP region R2 spanning over 11 residues encapsidated the corresponding viral RNAs. Also, all CP regions contained conservative and nonconservative amino acid changes. Thus, defects in encapsidation are more likely due to subtle structural changes and variations in thermodynamic properties of CP subunits that may or may not affect the assembly of virions. These subtle changes also likely have a cumulative effect since mutations that are individually not critical for encapsidation (G1, G2, or G4) become deleterious when combined (G12 and G24). Whether these explanations also account for the very poor infectivity of recombinant G2 is unknown.

Assuming that conformational changes occur during transmission, as demonstrated for Cucumber necrosis virus (CNV; genus Tombusvirus, family Tombusviridae [29]), it is not known whether the 11 residues in the βB-βC loop (Fig. 1 and 2) ensure a direct contact between GFLV virions and vector ligands or whether they are involved in a critical conformational structure. Regardless, GFLV CP region R2 is essential but may not be sufficient for transmission. Additional, as-yet-unidentified CP residues outside region R2 could contribute to transmission. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that we could not rule out the implication of CP regions R3, R4 and R5 in transmission due to loss of infectivity of the corresponding recombinants. Also, GFLV CP region R2 per se conferred a loss of transmission by X. index but no gain of transmission by X. diversicaudatum, suggesting a lack of reciprocity in the nature and/or location of CP transmission determinants between GFLV and ArMV. The failure of recombinant AA2 to encapsidate viral RNA, whereas recombinant AG2 was competent for encapsidation, further supports this view since substitutions affecting a priori equivalent CP subdomains did not have the same effect on virus encapsidation. However, we have to keep in mind that CP region R2 of ArMV may not adopt the same conformation within the GFLV CP relative to the ArMV CP and thus may not be recognized by nematode factors that confer transmission specificity.

According to our 3D homology-based GFLV models, CP region R2 overlaps the βB-βC loop within the B domain and sits closest to the βH-βI loop situated near the icosahedral 3-fold axis (Fig. 2). Remarkably, negatively charged residues of the CMV CP βH-βI loop play an essential role in transmission by aphids (19). Similarly, most residues critical for efficient CNV transmission by Olpidium spp. are located near a cavity formed by the particle 3-fold axis (18). It is therefore tempting to speculate that viral determinants necessary for nematode transmission of nepoviruses, aphid transmission of cucumoviruses, and Olpidium transmission of tombusviruses share common features and may be structurally related. Also, the BC and HI loops close to the 3-fold axis have been described to form a ring and suggested to be of importance for TRSV transmission (9). For CPMV, this same region constitutes a major antigenic site, demonstrating its accessibility (9).

GFLV recombinants carrying the CP region R1 predicted in the βE-αB external loop did not affect the transmissibility of recombinant viruses AG1 and G1 by X. index and X. diversicaudatum. Among the five CP regions identified from our GFLV 3D models, CP region R1 is the only one that is located within domain C. It is also the most distant from CP region R2. Since recombinants AG1 and G1 are infectious in planta, region R1 is likely not involved in the specific 2CCP-2BMP or virion-2BMP interactions required for tubule-guided GFLV movement through plasmodesmata (27, 6).

As hypothesized for GFLV (5) and ArMV (5, 23) and as demonstrated for CaMV (37), TVMV (7), and CNV (18), a deficiency in transmission results from the failure of the virus to bind or to be retained by specific vector factors. Whether AG2 fails to be retained in the vector mouthparts (8, 43) needs to be determined. If so, recombinant AG2 would be invaluable to unravel factor(s) involved in GFLV- and ArMV-specific recognition by X. index and X. diversicaudatum, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by a competitive grant from the European Commission (QLK3-CT-2002-02140) and the Ministère de l'Alimentation, de l'Agriculture et de la Pêche (CASDAR project 440). P.S. and P.A.-L. were supported by a fellowship from INRA, Département Santé des Plantes et Environnement, and the Conseil Interprofessionnel des Vins d'Alsace.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 June 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altshul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andret-Link, P., and M. Fuchs. 2005. Transmission specificity of plant viruses by vectors. J. Plant Pathol. 87:153-165. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andret-Link, P., C. Laporte, L. Valat, C. Ritzenthaler, G. Demangeat, E. Vigne, V. Laval, P. Pfeiffer, C. Stussi-Garaud, and M. Fuchs. 2004. Grapevine fanleaf virus: still a major threat to the grapevine industry. J. Plant Pathol. 86:183-195. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andret-Link, P., C. Schmitt-Keichinger, G. Demangeat, V. Komar, and M. Fuchs. 2004. The specific transmission of Grapevine fanleaf virus by its nematode vector Xiphinema index is solely determined by the viral coat protein. Virology 320:12-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belin, C., C. Schmitt, G. Demangeat, V. Komar, L. Pinck, and M. Fuchs. 2001. Involvement of RNA2-encoded proteins in the specific transmission of Grapevine fanleaf virus by its nematode vector Xiphinema index. Virology 291:161-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belin, C., C. Schmitt, F. Gaire, B. Walter, G. Demangeat, and L. Pinck. 1999. The nine C-terminal residues of the grapevine fanleaf nepovirus movement protein are critical for systemic virus spread. J. Gen. Virol. 80:1347-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanc, S., J. J. Lopez-Moya, R. Wang, S. Garcia-Lampasona, D. W. Thornbury, and T. P. Pirone. 1997. A specific interaction between coat protein and helper component correlates with aphid transmission of a potyvirus. Virology 231:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, D. J. F., W. M. Robertson, and D. L. Trudgill. 1995. Transmission of viruses by plant nematodes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 33:223-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandrasekar, V., and J. E. Johnson. 1998. The structure of tobacco ringspot virus: a link in the evolution of icosahedral capsids in the picornavirus superfamily. Structure 6:157-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, B., and R. I. Francki. 1990. Cucumovirus transmission by the aphid Myzus persicae is determined solely by the viral coat protein. J. Gen. Virol. 71:939-944. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demangeat, G., V. Komar, P. Cornuet, D. Esmenjaud, and M. Fuchs. 2004. Sensitive and reliable detection of grapevine fanleaf virus in a single Xiphinema index nematode vector. J. Virol. Methods 122:79-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gera, A., G. Loebenstein, and B. Raccah. 1979. Protein coats of two strains of cucumber mosaic virus affect transmission by Aphis gossypii. Phytopathology 69:396-399. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray, S. M., and N. Banerjee. 1999. Mechanisms of arthropod transmission of plant and animal viruses. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:128-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho, S. N., H. D. Hunt, R. M. Horton, J. K. Pullen, and L. R. Pease. 1989. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77:51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogenhout, S. A., D. Ammar el, A. E. Whitfield, and M. G. Redinbaugh. 2008. Insect vector interactions with persistently transmitted viruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 46:327-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huss, B., B. Walter, and M. Fuchs. 1989. Cross-protection between Arabis mosaic virus and Grapevine fanleaf virus isolates on Chenopodium quinoa. Ann. Appl. Biol. 114:45-60. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kakani, K., R. Reade, and D. Rochon. 2004. Evidence that vector transmission of a plant virus requires conformational change in virus particles. J. Mol. Biol. 338:507-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kakani, K., J. Y. Sgro, and D. Rochon. 2001. Identification of specific cucumber necrosis virus coat protein amino acids affecting fungus transmission and zoospore attachment. J. Virol. 75:5576-5583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu, S., X. He, G. Park, C. Josefsson, and K. L. Perry. 2002. A conserved capsid protein surface domain of Cucumber mosaic virus is essential for efficient aphid vector transmission. J. Virol. 76:9756-9762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loudes, A. M., C. Ritzenthaler, M. Pinck, M. A. Serghini, and L. Pinck. 1995. The 119 kDa and 124 kDa polyproteins of arabis mosaic nepovirus (isolate S) are encoded by two distinct RNA2 species. J. Gen. Virol. 76:899-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacFarlane, S. 2003. Molecular determinants of the transmission of plant viruses by nematodes. Mol. Plant Pathol. 4:211-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacFarlane, S. A., C. V. Wallis, and D. J. Brown. 1996. Multiple virus genes involved in the nematode transmission of pea early browning virus. Virology 219:417-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marmonier, A., P. Schellenberger, D. Esmenjaud, C. Schmitt-Keichinger, C. Ritzenthaler, P. Andret-Link, O. Lemaire, M. Fuchs, and G. Demangeat. 2010. The coat protein determines the specificity of virus transmission by Xiphinema diversicaudatum. J. Plant Pathol. 92:275-279. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreno, A., E. Hebrard, M. Uzest, S. Blanc, and A. Fereres. 2005. A single amino acid position in the helper component of cauliflower mosaic virus can change the spectrum of transmitting vector species. J. Virol. 79:13587-13593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng, J. C., and B. W. Falk. 2006. Virus-vector interactions mediating nonpersistent and semipersistent transmission of plant viruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44:183-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng, J. C., C. Josefsson, A. J. Clark, A. W. Franz, and K. L. Perry. 2005. Virion stability and aphid vector transmissibility of cucumber mosaic virus mutants. Virology 332:397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritzenthaler, C., M. Pinck, and L. Pinck. 1995. Grapevine fanleaf nepovirus P38 putative movement protein is not transiently expressed and is a stable final maturation product in vivo. J. Gen. Virol. 76:907-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritzenthaler, C., M. Viry, M. Pinck, R. Margis, M. Fuchs, and L. Pinck. 1991. Complete nucleotide sequence and genetic organization of grapevine fanleaf nepovirus RNA1. J. Gen. Virol. 72:2357-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rochon, D., K. Kakani, M. Robbins, and R. Reade. 2004. Molecular aspects of plant virus transmission by olpidium and plasmodiophorid vectors. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 42:211-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sali, A., and T. L. Blundell. 1993. Comparative protein modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234:779-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanfaçon, H. 2008. Nepovirus, p. 405-413. In B. W. J. Mahy and M. H. V. Van Regenmortel (ed.), Encyclopedia of virology, 3rd ed., vol. 3. Academic Press, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanfaçon, H., J. Wellink, O. Le Gall, A. Karasev, R. van der Vlugt, and T. Wetzel. 2009. Secoviridae: a proposed family of plant viruses within the order Picornavirales that combines the families Sequiviridae and Comoviridae, the unassigned genera Cheravirus and Sadwavirus, and the proposed genus Torradovirus. Arch. Virol. 154:899-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott, S. W., M. T. Zimmerman, A. T. Jones, and O. Le Gall. 2000. Differences between the coat protein amino acid sequences of English and Scottish serotypes of Raspberry ringspot virus exposed on the surface of virus particles. Virus Res. 68:119-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serghini, M. A., M. Fuchs, M. Pinck, J. Reinbolt, B. Walter, and L. Pinck. 1990. RNA2 of grapevine fanleaf virus: sequence analysis and coat protein cistron location. J. Gen. Virol. 71:1433-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Syller, J. 2006. The roles and mechanisms of helper component proteins encoded by potyviruses and caulimoviruses. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 67:119-130. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uzest, M., D. Gargani, M. Drucker, E. Hebrard, E. Garzo, T. Candresse, A. Fereres, and S. Blanc. 2007. A protein key to plant virus transmission at the tip of the insect vector stylet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:17959-17964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vellios, E., D. J. Brown, and S. A. MacFarlane. 2002. Substitution of a single amino acid in the 2b protein of Pea early-browning virus affects nematode transmission. J. Gen. Virol. 83:1771-1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vigne, E., A. Marmonier, and M. Fuchs. 2008. Multiple interspecies recombination events within RNA2 of grapevine fanleaf virus and Arabis mosaic virus. Arch. Virol. 153:1771-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viry, M., M. A. Serghini, F. Hans, C. Ritzenthaler, M. Pinck, and L. Pinck. 1993. Biologically active transcripts from cloned cDNA of genomic grapevine fanleaf nepovirus RNAs. J. Gen. Virol. 74:169-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vuittenez, M., M. C. Munck, and J. Kuszala. 1964. Souches de virus à haute aggressivité isolées de vignes atteintes de dégenerescence infectieuse. Etudes Virol. Appliquée 5:69-78. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walter, B., and L. Etienne. 1987. Detection of the grapevine fanleaf viruses away from the period of vegetation. J. Phytopathol. 120:355-364. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, S., R. C. Gergerich, S. L. Wickizer, and K. S. Kim. 2002. Localization of transmissible and nontransmissible viruses in the vector nematode Xiphinema americanum. Phytopathol. 92:646-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ziegler-Graff, V., and V. Brault. 2008. Role of vector-transmission proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 451:81-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.