Abstract

Between April 1999 and March 2008, a total of 4,976 stool specimens collected from patients with suspected viral infection through infectious agent surveillance in Aichi, Japan, were tested for the presence of human parechoviruses (HPeVs). We detected HPeVs in 110 samples by either cell culture, reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR), or both. Serotyping either by neutralization test or by nucleotide sequence determination and phylogenetic analysis of the VP1 region and 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) regions revealed that 63 were HPeV type 1 (HPeV-1), followed by 44 HPeV-3 strains, 2 HPeV-4 strains, and 1 HPeV-6 strain. The high nucleotide and amino acid sequence identities of the Japanese HPeV-3 isolates in 2006 to the strains previously reported from Canada and Netherlands confirmed the worldwide prevalence of HPeV-3 infection. Ninety-seven percent of the HPeV-positive patients were younger than 3 years, and 86.2% younger than 12 months. The clinical diagnoses of HPeV-positive patients were gastroenteritis, respiratory illness, febrile illness, exanthema, “hand, foot, and mouth disease,” aseptic meningitis, and herpangina. Among 49 HPeV-positive patients with gastroenteritis, 35 were positive with HPeV-1 and 12 with HPeV-3, and out of 25 with respiratory illness, 11 were positive with HPeV-1 and 14 with HPeV-3. HPeV-3 seemed to be an important etiological agent of respiratory infection of children. While HPeV-1 was detected predominantly during fall and winter, the majority of the HPeV-3 cases were detected during summer and fall. A different pattern of clinical manifestations as well as seasonality suggested that there are different mechanisms of pathogenesis between HPeV-1 and HPeV-3 infections.

Human parechoviruses (HPeVs) are members of the family Picornaviridae and are classified into 14 known genotypes (3, 4, 6, 11, 15, 17, 18, 21, 25, 36, 37, 39). HPeV type 1 (HPeV-1) and HPeV-2, previously known as echovirus 22 (E-22) and 23 (E-23), respectively, were first isolated in 1956. While HPeV-2 infection appears to be rare (2, 13, 20, 29), HPeV-1 is prevalent worldwide. HPeV-3 was recently isolated in our laboratory from a stool specimen of a young child with transient paralysis (18) and has been also reported to be detected in specimens from critically ill children who were reported to have viremia, neonatal sepsis, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (1, 2, 5, 33, 38). HPeV-4 was first reported in 2006 from a stool specimen of a 6-day-old infant with a 2-day history of high fever and poor feeding (4). CT86-8760 (Connecticut/86), formerly typed as E-23 (HPeV-2) by neutralization test (29), was recently reclassified as the fifth type of HPeV (HPeV-5) based on the phylogenetic analysis of the VP1 region (3). Recently, the sixth type of HPeV (HPeV-6) was isolated from cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with Reye syndrome (38). The seventh type of HPeV (HPeV-7) was found in a stool sample from a healthy boy who had close contact with a person who had nonpolio acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) in Pakistan (25). The eight type of HPeV (HPeV-8) was detected by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) in a stool sample from a child with enteritis in Brazil (11). The 14th type of HPeV (HPeV-14) was found in a stool sample from a child in Netherlands (7). The nucleotide sequences of new HPeV strains, i.e., genotypes 9 to 13, have not been published so far.

Several previous studies established and improved the sensitivity of HPeV detection from stool specimens (10, 24, 30), but the full spectrum of clinical manifestations and the epidemiology of HPeV infection, as well as the prevalence and pathogenesis of each HPeV type, still remain undetermined. In an attempt to characterize the epidemiologic and pathogenic aspects of each HPeV serotype, we here report the incidence and clinical features of HPeV infection in children based on the analyses of epidemiological information and stool specimens collected from approximately 5,000 patients visiting pediatric clinics during a recent 10-year period as a routine surveillance system to identify the prevalence of viral pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical specimen collection.

Specimens were collected as part of the National Epidemiological Surveillance of Infectious Diseases, in which 29 medical institutions in the Aichi Prefecture (except for the Nagoya City area) were enrolled as the sentinels for infectious agent surveillance. Between April 1999 and March 2008, a total of 4,976 stool specimens were collected from patients with suspected viral infection (Table 1). All specimens were collected after the parents of the enrolled children had given informed consent. Demographic and clinical information was extracted from the patient record provided by the attending physician for each specimen. The clinical diagnoses of these patients are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Detection of HPeVs in 4,976 fecal samples obtained between April 1999 and March 2008 in Aichi Prefecture, Japan

| Yr | No. of samplesa |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Positive | With: |

||||

| HPeV-1 | HPeV-3 | HPeV-4 | HPeV-6 | |||

| 1999 (April-December) | 748 | 22 (16) | 9 (5) | 13 (11) | 0 | 0 |

| 2000 | 738 | 14 (5) | 11 (5) | 3 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| 2001 | 263 | 7 (4) | 4 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| 2002 | 274 | 10 (8) | 5 (3) | 5 (5) | 0 | 0 |

| 2003 | 327 | 10 (1) | 6 (1) | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 2004 | 482 | 13 (10) | 10 (8) | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| 2005 | 528 | 12 (8) | 12 (8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2006 | 837 | 16 (16) | 1 (1) | 14 (14) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| 2007 | 674 | 6 (6) | 5 (5) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| 2008 (January-March) | 105 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 4,976 | 110 (74) | 63 (37) | 44 (34) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

Numbers in parenthesis indicate the number of cell culture-positive samples.

TABLE 2.

Detection of HPeVs in fecal samples from patients with various clinical manifestations

| Clinical symptom | No. (%) of patients with: |

No. (%) of patients tested | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPeV | HPeV-1 | HPeV-3 | HPeV-4 | HPeV-6 | ||

| Gastroenteritis | 49 (44.5) | 35 (55.6) | 12 (27.3) | 2 | 0 | 2,204 (44.3) |

| Respiratory illness | 25 (22.7) | 11 (17.5) | 14 (31.8) | 0 | 0 | 735 (14.8) |

| Undifferentiated febrile illness | 14 (12.7) | 8 (12.7) | 6 (13.6) | 0 | 0 | 190 (3.8) |

| Exanthema | 10 (9.1) | 6 (9.5) | 4 (9.1) | 0 | 0 | 106 (2.1) |

| Hand-foot-mouth disease | 7 (6.4) | 2 (3.2) | 5 (11.4) | 0 | 0 | 274 (5.5) |

| Aseptic meningitis | 4 (3.6) | 1 (1.6) | 3 (6.8) | 0 | 0 | 249 (5) |

| Herpangina | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 193 (3.9) |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,025 (20.6) |

| Total | 110 (100) | 63 (100) | 44 (100) | 2 | 1 | 4,976 (100) |

Virus isolation from stool specimens and serotyping.

Feces were diluted with veal infusion broth to 10% (wt/vol) suspensions and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was inoculated onto HeLa and Vero cells and observed for up to 2 weeks, followed by subpassage to fresh cells for an additional 2-week observation for the presence of cytopathic effects (CPE). Following the emergence of CPE, serotyping of each virus isolate was performed by neutralization test (26) using type-specific antisera, i.e., anti-HPeV-1 (Harris strain) distributed from the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan, and anti-HPeV-3 (A308/99 strain) prepared in this laboratory as pooled guinea pig immune serum.

RT-PCR and sequencing.

Nucleic acid was extracted directly from the sample stool suspension prepared as described above and also from the supernatant of inoculated cell cultures using either the QIAamp viral RNA (DNA) mini kit (Qiagen) or the High Pure viral RNA kit (Roche) according to each manufacturer's instructions.

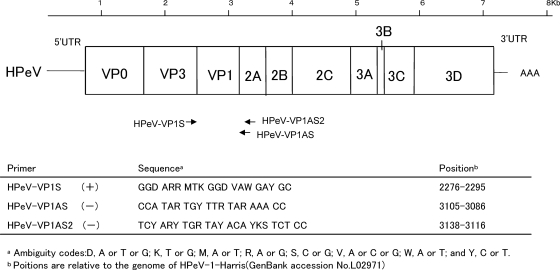

RT-PCR was performed using the one-step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturer. For amplification of part of the 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR), the HPeV PCR ev22 (+) and (−) primer pair (19) was used. In addition, the amplification of the nucleotides in the VP1 region was performed using the following primers designed by comparison of the six known HPeV serotypes (Fig. 1): a forward primer with a sequence of 5′-GGD ARR MTK GGD VAW GAY GC-3′ (HPeV-VP1S), a reverse primer with a sequence of 5′-CCA TAR TGY TTR TAR AAA CC-3′ (HPeV-VP1AS), and a nested-PCR reverse primer with a sequence of 5′-TCY ARY TGR TAY ACA YKS TCT CC-3′ (HPeV-VP1AS2). The cycling conditions were as follows: 50°C for 30 min; 95°C for 1 min; 35 cycles consisting of 94°C for 1 min, 42°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 90 s; and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Amplicons were detected by 0.5% Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) agarose gel electrophoresis and staining with ethidium bromide.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the parechovirus genome and locations of the primer sites.

All samples from gastroenteritis patients were tested for the detection of norovirus (22), rotavirus (16), and adenovirus (34) using PCRs, which were performed according to the previously published protocols.

Selected PCR-amplified products were purified and introduced into a pGEM-T vector (Promega). The DNA sequence was determined with an automated DNA sequencer (model 4000; Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE). Each serotype was determined by the comparison of the nucleotide sequence with the available HPeV sequences from GenBank using the Genetyx program (Genetix, New Milton, Hampshire, United Kingdom).

Phylogenetic tree analysis.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of amplified VP1 regions were aligned with those of representative HPeV strains by using the Genetyx and Neighbor software package of the Phylip program in the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) package. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the unweighted pair group method with averages (UPGMA) in the same package. The following nucleotide sequences were obtained from GenBank: HPeV-1 (Harris strain), L02971; HPeV-1 (BNI-788st strain), EF051629; HPeV-2 (Williamson strain), AJ005695; HPeV-3 (A308-99 strain), AB084913; HPeV-3 (Can82853-01 strain), AJ889918; HPeV-4 (K251176-02 strain), DQ315670; HPeV-4 (T75-4077 strain), AM235750; HPeV-5 (Connecticut/86-6760 strain), AF055846; HPeV-5 (T92-15 strain), AM235749; HPeV-6 (NII561-2000 strain), AB252582; HPeV-6 (BNI-67-03 strain), EU024629; HPeV-7 (PAK5045 strain), EU556224; HPeV-8 (BR217 2006 strain), EU716175; HPeV-14 (451564 NL,2004 strain), FJ373179; Ljungan virus, AF327920; and published isolates for HPeV-1 and HPeV-3.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the HPeV strains reported in this paper were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers AB300926 to AB300986 and AB469777 to AB469782.

RESULTS

Detection of HPeVs in clinical specimens.

Out of 4,976 samples, 110 (2.2%) were positive for HPeVs either by RT-PCR using primers for the 5′UTR region alone or by both virus isolation and RT-PCR (Table 1).

HPeVs were isolated from 74 of 4,976 samples (1.5%). All culture-positive samples were also positive by RT-PCR as described below. Out of 110 samples that were positive for 5′UTR amplification, 62 were also positive for VP1 amplification and were typed as described in the next section. Among 38 samples that were negative for VP1 amplification, 5 of them were positive for HPeV isolation, i.e., 1 HPeV-1 strain and 4 HPeV-3 strains. The remaining 33 were identified as 23 HPeV-1 strains and 10 HPeV-3 strains using 5′UTR sequences with 100% bootstrap support for the standard strain and isolations identified by neutralizing test. In addition, 5′UTR amplicons from the five VP1-negative specimens mentioned above were also typed accordingly.

Of 74 isolates, 71 (95.9%) could be typed by the neutralization test using the antisera against HPeV-1 and HPeV-3; 37 (50%) typed as HPeV-1 and 34 (45.9%) as HPeV-3. The serotypes of the remaining three isolates were determined as HPeV-4 (two isolates) and HPeV-6 (one isolate) by molecular characterization. HPeV nucleotide sequences were detected in 110 of 4,976 samples (2.2%) by RT-PCR. Of 110 amplicons, 63 (57.2%) were typed as HPeV-1, 44 (40%) were HPeV-3, 2 were HPeV-4, and 1 was HPeV-6.

Copathogens were also found in 8 (10.8%) of 74 samples positive for HPeV isolation. Out of these eight samples, two were positive for norovirus genotype II, and the remaining six samples were positive for one of the following viruses: enterovirus 71, norovirus genotype I, group A rotavirus, adenovirus 2, adenovirus 41, or coxsackievirus A8 (Cox.A8). Enterovirus 71 was isolated from a patient with hand, foot, and mouth disease; Cox.A8 was from a patient with herpangina; and the remaining six were from patients with gastroenteritis.

Genome sequence determination and phylogenetic analysis of the VP1 region.

Out of 4,976 samples, amplification of the VP1 region by RT-PCR was successful for 72 samples (1.4%), all of which were also positive for 5′UTR amplification. The nucleotide sequences of these amplicons were determined and utilized for serotyping as described below.

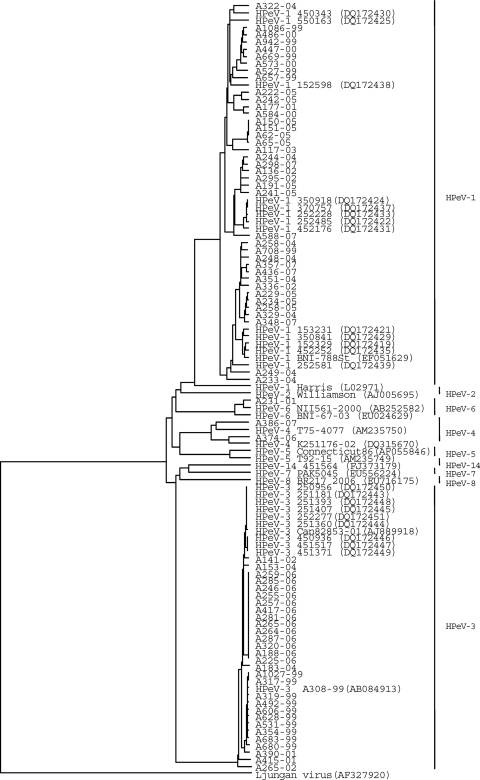

Serotypes were determined based on the nucleotide sequence of the entire VP1 region. A phylogenetic tree was constructed with these data and also with the partial nucleotide sequences of the published strains (Fig. 2). Our HPeV-1 isolates (n = 39) were only 73.4 to 78.6% similar to the prototype Harris strain and formed several clusters, and they were related to those recent clinical isolates reported from Netherlands and Germany. Nucleotide sequences of HPeV-1 isolates comprising different clusters showed a 16.5% difference from each other. Clustering was independent from chronological and geographical distribution, seasonality of sample collection, or clinical manifestations.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of HPeV isolates and prototype based on nucleotide sequences of the VP1 region. The corresponding gene sequences of previously reported Canadian, Dutch, and German isolates are also included. The dendrograms were generated by evolutionary distances, as computed by UPGMA. The isolates reported in this study are indicated by the isolate number and the year (e.g., A322-04).The Canadian isolate is indicated by Can82853-01.The Germany isolate is indicated by BNI-788St. The Dutch isolates are indicated by GenBank accession numbers DQ172419 to DQ172450.

All 29 HPeV-3 sequences determined in this study were related not only to the prototype A308-99 but also to the isolates reported from Canada and Netherlands. These strains showed 91.4 to 100% identity to each other and formed the same branch of the VP1 tree, indicating a common ancestor prevalent in the world.

The intratypic nucleotide (amino acid) similarity in the VP1 regions of HPeV-1, HPeV-3, HPeV-4, and HPeV-6 were 64 to 72% (62 to 81%), 64 to 70% (62 to 77%), 67 to 71% (65 to 78%), and 65 to 71% (67 to 81%), respectively.

Demographic features of HPeV-positive patients.

The age at the specimen sampling was known for 106 of the 107 HPeV-positive patients, with the mean age being 12.9 months. All 63 children positive for HPeV-1 were younger than 5 years (except for the one unknown), and 55 (87.3%) were less than 1 year, with an average of 13 months; similarly, all 44 who were positive for HPeV-3 were younger than 6 years of age, and 38 (86.3%) were less than 1 year, with an average of 12.1 months.

The male-to female ratios were 2.4 to 1 (44 versus 18) for patients with HPeV-1 and 1.32 to 1 (25 versus 19) for HPeV-3. The male-to-female ratio for all of the stool samples was 1.3 to 1 (2,818 versus 2,144, except for 14 unknown).

Clinical manifestations in HPeV-positive patients.

From stool specimens collected from pediatric outpatients, HPeV was isolated every year from 1999 to 2007, most frequently in 1999 (22) and least frequently in 2007 (6) (Table 1). The clinical diagnoses of these 110 HPeV-positive patients are summarized in Table 2. The most common diagnosis was gastroenteritis, followed by respiratory illness, unspecified febrile illness, exanthema, “hand, foot, and mouth disease,” aseptic meningitis, and herpangina. Among the 63 patients who were positive for HPeV-1, 35 (55.6%) were diagnosed as having gastroenteritis and 11 (17.5%) as having respiratory illness. In contrast, of 44 HPeV-3-positive patients, 14 (31.8%) had respiratory illness, followed by 12 (27.3%) with gastroenteritis.

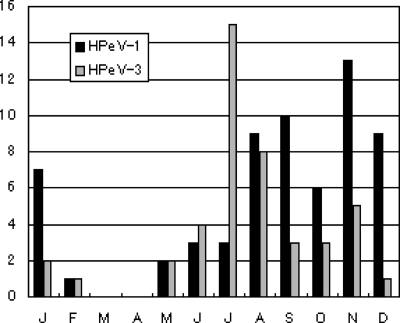

Overall, both HPeV-1 and -3 were detected almost throughout the year, but a certain distinct seasonality was observed for both serotypes. Fifty-four (85.7%) out of 63 HPeV-1-positive samples were collected from August to January, and 33 of them (33/54, 61%) were associated with gastrointestinal symptoms. In comparison, HPeV-3 appeared a couple of months earlier than HPeV-1, and 38 (86.4%) of 44 HPeV-3-positive samples were collected during June to November (Fig. 3). In particular, 11 (91.7%) of 12 HPeV-3-positive specimens associated with gastrointestinal symptoms were collected during July and November.

FIG. 3.

Histogram of monthly distribution of RT-PCR-positive clinical cases for HPeV between 1999 and 2008.

The two HPeV-4 strains were detected in August and November, respectively, both from samples derived from patients with gastroenteritis. HPeV-6 was detected in one sample which had been collected in June from a patient with herpangina and also positive for Cox.A8.

DISCUSSION

HPeVs have been classified into six serotypes based on neutralization test or molecular identification, and at least three new serotypes (HPeV-7, -8, and -14) have been identified (3, 4, 6, 7, 11, 15, 17, 18, 25, 39). Clinical manifestations that have been associated with HPeV infections include gastroenteritis, respiratory diseases, aseptic meningitis, encephalomyelitis, AFP, lymphadenopathy, myocarditis, hemolytic uremic syndrome, neonatal sepsis-like syndromes with necrotizing enterocolitis, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), notably in young children (1-15, 18, 19, 23-25, 27, 28, 32, 33, 35, 39). We therefore tested stool specimens collected from children visiting pediatric clinics with suspected viral infections between 1999 and 2008 for HPeV-3 as well as the other HPeVs, and we detected HPeV in 110 (2.2%) of 4,976 samples by RT-PCR. To our knowledge, this is the first description of routine surveillance findings in which a new and improved method directed specifically for detection of all six types of HPeVs has been applied.

To determine the efficiency of current molecular diagnostic methods using HPeV VP1 and/or 5′UTR sequences obtained by RT-PCR (2, 5, 18, 19, 30), we performed RT-PCR which detects HPeV-1, -3, -4, and -6 simultaneously, in parallel with conventional virus isolation using Vero and HeLa cell culture. We evaluated the incidence over a full year by RT-PCR testing and cell culture. We conclude that the RT-PCR method as well as cell culture can be recommended as the primary diagnostic tool for HPeV infections, using confirmation by cell culture for isolation of copathogens and new strains that are untypeable by using the sequences of RT-PCR products.

In addition, we designed a new RT-PCR primer that amplifies the VP1 regions of all six known serotypes of HPeV. Phylogenetic analysis using the VP1 region was possible for 72 of 110 HPeV RNA-positive samples (65.5%). There were 33 samples from which the VP1 sequence could not be amplified by the current RT-PCR protocol, and these were typed by comparing 5′UTR sequences to those of the standard strain/isolate with 100% bootstrap support. As 5′UTR sequences tend to be highly conserved and therefore not entirely suitable for serotyping (31, 38), development of a more sensitive RT-PCR protocol for the VP1 region is required. Still, molecular typing methods have been established to circumvent practical problems associated with traditional serum neutralization and provide indispensable supporting data for serotyping. In this study, two HPeV-4 isolates and one HPeV-6 isolate that were not neutralized with anti HPeV-1, -2, and -3 sera were typed solely by the molecular methods described above. Viral genomic sequences should also be useful for the identification of previously unreported genotypes. They also provide essential information for the determination of specific molecular target sequences for virus identification.

By phylogenetic analysis of HPeV-1, each of our HPeV-1 isolates belonged to several clusters, with no specific temporal or geographic patterns. In contrast to the case for HPeV-1, we could identify close similarity between HPeV-3 strains (Fig. 2).

Of the 110 children positive for HPeVs, HPeV-3 was second most important pathogen, following HPeV-1. As reported previously for samples from Europe (5) and North America (2), we confirmed that HPeVs are associated not only with gastroenteritis but also with respiratory illness in young children. While HPeV-1 was most prevalent in patients with gastroenteritis, representing almost 55.6% of the cases, HPeV-3 seems to be responsible not only for gastroenteritis but also, or more notably, for respiratory symptoms.

Whereas HPeV-1 did not seem to be involved in central nervous system (CNS) infections, HPeV-3 has been reported to be associated with sepsis-like illness, CNS involvement, or cases of SIDS (1, 33). While we could not determine the involvement of HPeV-3 in these serious clinical situations, it should be noted that HPeV-3 was detected in nine samples from unrelated patients, six with febrile illness and three with aseptic meningitis. Although HPeV was detected throughout the year, we noticed a different pattern of seasonality between HPeV-1 and HPeV-3, suggesting different pathogeneses of these two serotypes.

All HPeV-positive samples obtained in this study were from children who were 6 years or younger, with the majority (96/109, 88.1%) being younger than 1 year of age. Previous seroepidemiology revealed that the proportion of seropositive individuals increases rapidly with age, reaching 75 to 100% by 6 years of age in this area for both HPeV-1 and HPeV-3 (18). These results suggested that both HPeV-1 and -3 are endemic and that most HPeV infections occur in the pediatric population. More HPeV infections were observed in male than in female patients. In particular, HPeV-1 was detected in males 2.5 times more than in females, indicating a need to further investigate if there is any different susceptibility between the sexes.

HPeV-4 was recently isolated from a stool specimen of a 6-day-old patient with fever and poor feeding and no history of specific gastrointestinal or respiratory symptoms in Netherlands. In our study, the two HPeV-4 strains, A374-06 and A386-07, were both isolated from patients with gastroenteritis, aged 2 months and 1 year, respectively. Adenovirus 2 was also detected from the stool sample with A386-07. HPeV-6 was first reported from a cerebrospinal fluid specimen of a patient with Reye syndrome in Niigata, Japan (NII561-2000 in Fig. 2) (39). In this study, the HPeV-6 isolate (A231-01) was isolated from the stool of an 11-month-old patient with herpangina, whose throat swab was positive for Cox.A8. Since we detected only two HPeV-4 strains and one HPeV-6 strain in this 9-year surveillance, both HPeV-4 and -6 are either less related to disease manifestations or less prevalent, or both, in the Aichi area than HPeV-1 and -3. Further research, especially on both case- and sentinel-based surveillances, is needed to clarify the prevalence and etiological importance of each serotype of HPeV in the general population.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abed, Y., and G. Boivin. 2005. Molecular characterization of a Canadian human parechovirus (HPeV)-3 isolate and its relationship to other HPeVs. J. Med. Virol. 77:566-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abed, Y., and G. Boivin. 2006. Human parechovirus infections in Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:969-975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Sunaidi, M., C. H. Williams, P. J. Hughes, D. P. Schunurr, and G. Stanway. 2007. Analysis of a new human parechovirus allows the definition of parechovirus types and the identification of RNA structural domains. J. Virol. 81:1013-1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benschop, K. S. M., J. Schinkel, M. E. Luken, P. J. M. Broek, M. F. Beersma, N. Menelik, H. W. Eijk, H. L. Zaaijer, C. M. VandenBroucke-Grauls, M. G. Beld, and K. C. Wolthers. 2006. Fourth human parechovirus seyotype. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:1572-1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benschop, K. S. M., J. Schinkel, R. P. Minnaar, D. Pajkrt, L. Spanjerberg, H. C. Kraakman, B. Berkhout, H. L. Zaaijer, M. G. Beld, and K. C. Wolthers. 2006. Human parechovirus infections in Dutch children and the association between serotype and disease severity. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42:204-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benschop, K. S. M., G. Stanway, and K. C. Wolthers. 2008. New human parechoviruses: six and counting, p. 53-74. In W. M. Scheld, S. M. Hammer, and J. M. Hughes, (ed.), Emerging infections 8. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 7.Benschop, K., X. Thomas, C. Serpenti, R. Molenkamp, and K. Wolthers. 2008. High prevalence of human parechovirus (HPeV) genotypes in the Amsterdam region and identification of specific HPeV variants by direct genotyping of stool samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3965-3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birenbaum, E., R. Handsher, J. Kuint, R. Dagan, B. Raichman, E. Mendelson, and N. Linder. 1997. Echovirus type 22 outbreak associated with gastro-intestinal disease in a neonatal intensive care unit. Am. J. Perinatol. 14:469-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coller, B. A. G., N. M. Chapman, M. A. Beck, M. A. Pallansch, C. J. Gauntt, and S. M. Tracy. 1990. Echovirus 22 is an atypical entrovirus. J. Virol. 64:2692-2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corless, C. E., M. Guiver, R. Borrow, V. Edward-Jone, A. J. Fox, E. B. Kaczmarski, and K. J. Mutton. 2002. Development and evaluation of ‘real-time’ RT-PCR for the detection of enterovirus and parechovirus RNA in CSF and throat swab samples. J. Med. Virol. 67:555-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drexler, J. F., K. Grywna, A. Stocker, P. S. Almeida, T. C. Medrado-Ribeiro, M. Eschbach-Bludau, N. Petersen, H. da Costa-Ribeiro, Jr., and C. Drosten. 2009. Novel human parechovirus from Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:310-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrnst, A., and M. Eriksson. 1993. Epidemiological features of type 22 Echovirus infection. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 25:275-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehrnst, A., and M. Eriksson. 1996. Echovirus type 23 observed as a nosocomial infection in infants. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 28:205-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Figueroa, J. P., D. Ashley, D. King, and B. Hull. 1989. An outbreak of acute flaccid paralysis in Jamaica associated with echovirus type 22. J. Med. Virol. 29:315-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghazi, F., P. J. Hughes, T. Hyypia, and G. Stanway. 1998. Molecular analysis of human parechovirus type 2 (formerly echovirus 23). J. Gen.Virol. 79:2641-2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gouvea, V., R. I. Glass, P. Woods, K. Taniguchi, H. F. Clark, B. Forrester, and Z.-Y. Fang. 1990. Polymerase chain reaction amplification and typing of rotavirus nucleic acid from stool specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:276-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyypia, T., C. Horsnell, M. Maaronen, M. Khan, N. Kalkkinen, P. Auvinen, L. Kinnunen, and G. Stanway. 1992. A distinct picornavirus group identified by sequence analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:8847-8851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito, M., T. Yamashita, H. Tsuzuki, N. Takeda, and K. Sakae. 2004. Isolation and identification of a novel human parechovirus. J. Gen.Virol. 85:391-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joki-Korpela, P., and T. Hyypia. 1998. Diagnosis and epidemiology of echovirus 22 infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joki-Korpela, P., and T. Hyypia. 2001. Parechovirus. A novel group of human picornavirus. Ann. Med. 33:466-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King, A. M. Q., F. Brown, P. Christian, T. Hovi, T. Hyypia, N. J. Knowles, S. M. Lemon, P. D. Minor, A. C. Palmenberg, T. Skern, and G. Stanwey. 1999. Picornaviridae in virus taxonomy, p. 657-673. In C. Regenmortel, M. Fauquet, D. H. L. Bishop, C. H. Calisher, E. B. Carsten, M. K. Estes, S. M. Lemon, J. Maniloff, M. A. Mayo, D. J. McGeoch, C. R. Pringle, and R. B. Wickner (ed.), Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, New York, NY.

- 22.Kojima, S., T. Kageyama, S. Fukushi, F. B. Hoshino, M. Shinohara, K. Uchida, K. Natori, N. Takeda, and K. Katayama. 2002. Genogroup-specific PCR primers for detection of Norwalk-like viruses. J. Virol. Methods 100:107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koskiniemi, M., R. Paetau, and K. Linnavuori. 1989. Severe encephalitis associated with disseminated echovirus 22 infection. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 21:463-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Legay, V., J. J. Chhomel, and B. Lina. 2002. Specific RT-PCR procedure for the detection on human prechovirus type I genome in clinical samples. J. Virol. Methods 102:157-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, L., J. Victoria, A. Kapoor, A. Naeem, S. Shaukat, S. Sharif, M. M. Alam, M. Angez, S. Z. Zaidi, and E. Delwart. 2009. Genomic characterization of novel human parechovirus type. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:288-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melnick, J. L., H. A. Wenner, and C. A. Phillips. 1979. Enteroviruses, p. 471-534. In E. H. Lennette and N. J. Schmidt (ed.), Diagnostic procedures for viral, rikettsial and chlamydial infections, 5th ed. American Public Health Association, Washington, DC.

- 27.Muir, P., U. Kammerer, K. Koru, M. N. Mulders, T. Doyry, B. Weissbrich, R. Kandolf, G. M. Cleator, and A. M. Vanloon. 1998. Molecular typing of enteroviruses: current status and future requirements. The European Union concerted action on virus meningitis and encephalitis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1:202-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakao, T., and R. Miura. 1970. ECHO virus type 22 infection in a premature infant. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 102:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, and M. A. Pallansch. 1998. Complete sequence of echovirus 23 and its relationship to echovirus 22 and other human enterovirus. Virus Res. 56:217-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, and M. A. Pallansch. 1999. Specific detection of echovirus 22 and 23 in cell culture supernatants by RT-PCR. J. Med. Virol. 58:178-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, D. R. Kilpatrick, and M. A. Pallansch. 1999. Molecular evolution of the human enteroviruses: correlation of serotype with VP1 sequence and application to picornavirus classification. J. Virol. 73:1941-1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schnurr, D., M. Dondero, M. Holland, and J. Connor. 1996. Characterization of echovirus 22 variants. Arch.Virol. 141:1749-1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sedmack, G., and J. Jentzen. 2005. Human parechovirus type3 (HPeV-3) association with three infant deaths in Wisconsin from September 2003 through August 2004, abstr. T-22. Abstr. Assoc. Public Health Lab.Infect. Dis. Conf., Orlando, FL, 2 to 4 March 2005.

- 34.Shimada, Y., T. Ariga, Y. Tagawa, K. Aoki, S. Ohno, and H. Isiko. 2004. Molecular diagnosis of human adenoviruses D and E by a phylogeny-based classification method using a partial hexon sequence. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1577-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanway, G., N. Kalkkinen, M. Roivainen, F. Ghazi, M. Khan, M. Smyth, O. Meurman, and T. Hyypia. 1994. Molecular and biological characteristics of echovirus 22, a representative of a new picornavirus group. J. Virol. 68:8232-8238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanway, G., and T. Hyypia. 1999. Parechoviruses. J. Virol. 73:5249-5254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanway, G., P. Joki-Korpela, and T. Hyypia. 2000. Human parechoviruses. Biology and clinical significance. Rev. Med. Virol. 10:57-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thoelen, L., E. Moes, P. Lemey, S. Mostmans, E. Wollants, A. M. Lindberg, A. M. Vandamme, and M. V. Ranst. 2004. Analysis of the serotype and genotype correlation of VP1 and the 5′noncoding region in an epidemiological survey of the human enterovirus B species. J. Clin.Microbiol. 42:963-971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watanabe, K., M. Oie, M. Higuchi, M. Nishikawa, and M. Fujii. 2007. Isolation and characterization of novel human parechovirus from clinical samples. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13:889-895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]