Abstract

Most Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variants (SCVs) are auxotrophs for menadione, hemin, or thymidine but rarely for CO2. We conducted a prospective investigation of all clinical cases of CO2-dependent S. aureus during a 3-year period. We found 14 CO2-dependent isolates of S. aureus from 14 patients that fulfilled all requirements to be considered SCVs, 9 of which were methicillin resistant. The clinical presentations included four cases of catheter-related bacteremia, one complicated by endocarditis; two deep infections (mediastinitis and spondylodiscitis); four wound infections; two respiratory infections; and two cases of nasal colonization. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing showed that the 14 isolates were distributed into 4 types corresponding to sequence types ST125-agr group II (agrII), ST30-agrIII, ST34-agrIII, and ST45-agrI. An array hybridization technique performed on the 14 CO2-dependent isolates and 20 S. aureus isolates with normal phenotype and representing the same sequence types showed that all possessed the enterotoxin gene cluster egc, as well as the genes for α-hemolysin and δ-hemolysin; biofilm genes icaA, icaC, and icaD; several microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMM) genes (clfA, clfB, ebh, eno, fib, ebpS, sdrC, and vw); and the isaB gene. Our study confirms the importance of CO2-dependent SCVs of S. aureus as significant pathogens. Clinical microbiologists should be aware of this kind of auxotrophy because recovery and identification are challenging and not routine. Further studies are necessary to determine the incidence of CO2 auxotrophs of S. aureus, the factors that select these strains in the host, and the genetic basis of this type of auxotrophy.

Small-colony variants (SCVs), formerly designated “G” (gonidial) variants or dwarf colonies, constitute a naturally occurring, slow-growing subpopulation of bacteria with distinctive phenotypic characteristics and pathogenic traits (25). Although SCVs have been described in a wide range of bacterial genera and species and recovered from different clinical specimens, including abscesses and soft tissues, blood and bone, joints, and the respiratory tract, those of Staphylococcus aureus have been most extensively studied (14). Most of these SCVs are auxotrophs for menadione, hemin, or thymidine, while others are occasionally identified as auxotrophs for CO2 (14).

Although the prevalence of SCVs of S. aureus in clinical specimens in a general microbiology laboratory has been estimated to be around 1% (1), SCVs are recovered more frequently from certain groups of patients such as those with cystic fibrosis (14, 15). A recent study determined the prevalence of SCVs to be 17% among cystic fibrosis patients who carried S. aureus (2). These SCVs were thymidine auxotrophs, a characteristic related to long-term exposure to prophylactic treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (2, 23). Several investigators have also shown that SCVs of S. aureus can often be recovered from cultures of patients who have been exposed to gentamicin or other aminoglycosides (11, 14). Hemin- and menadione-auxotrophic S. aureus SCVs have been recovered from patients with osteomyelitis who were treated with gentamicin (23). SCVs of S. aureus have also been recovered from patients with device-related infections (17). In general, the characteristics of SCVs facilitate persistence and recurrence of infections (7, 13, 14, 24). Moreover, clinical cases of endocarditis, bacteremic pneumonia, and abscesses due to strains of CO2-dependent staphylococcus producing dwarf colonies have rarely been described in the medical literature (16, 19-21).

After observing S aureus SCVs in two patients who were hospitalized in the same surgical ward, we noted that both cases were likely to have been caused by nosocomial transmission of a strain of S. aureus that was auxotrophic for CO2. After that, we decided to conduct a prospective study of all clinical cases caused by CO2-dependent S. aureus. Here we describe the clinical characteristics of the cases that we identified together with the phenotypic and genetic characterization of the SCVs isolated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and chart review.

This study was conducted at the Hospital Universitario Doce de Octubre, a 1,300-bed tertiary care facility that comprises two separate buildings, one for children and the other for adults. This public hospital provides specialized health care to a population of approximately 550,000 residents in southern Madrid, Spain. All patients with CO2-dependent SCV isolates of S. aureus that were recovered between 2006 and May 2009 were included in the study. We reviewed the medical charts from each of these patients and collected demographic, clinical, and microbiological data.

Microbiology.

Staphylococcus aureus SCVs were identified as slow-growing, pinpoint, nonpigmented, nonhemolytic colonies after 24 to 48 h of incubation in air on Trypticase soy agar with 5% sheep blood. All isolates that were morphologically consistent with SCVs of S. aureus were subcultured on sheep blood agar at 37°C and incubated both aerobically and in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. In order to generate an anaerobic atmosphere, we used Genbox anaer (bioMérieux, Lyon, France). Identification tests comprised agglutination with Staphaurex Plus (Remel Europe, United Kingdom), coagulase analysis, and the Wider system (Soria Melguizo, Madrid, Spain). Confirmation of identification was done by sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed with Wider panels (Soria Melguizo, Madrid, Spain) (3), based on the broth microdilution method, and was interpreted using the criteria of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (5). Disk diffusion analysis was also performed at 35°C for oxacillin and cefoxitin, in air and in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. All S. aureus SCV isolates underwent PCR analysis for the mecA gene (12).

Auxotrophy testing was done as previously described (7). Briefly, auxotrophy for hemin was tested using standard commercial disks, and that for thymidine and menadione was tested by impregnating disks with 15 μl of thymidine (Fluka Biochemika) at 100 μg/ml or menadione (Sigma Aldrich) at 10 μg/ml on Mueller-Hinton agar, respectively.

Molecular typing and microarray-based genotyping.

Molecular characterization of isolates was performed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) following DNA extraction and digestion with SmaI according to previously described methods (4). Computer-assisted analysis of electropherograms was carried out with Bionumerics software (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). A 1.8% tolerance was used for comparisons of DNA patterns. Additionally, methicillin-resistant isolates of S. aureus (MRSA) underwent PCR characterization of the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) (12). All S. aureus SCV isolates were analyzed by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) as described previously (6), and sequence types (STs) were assigned by using the MLST website (http//www.mlst.net).

DNA microarrays based on the ArrayTube platform were run according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clondiag, Jena, Germany). The array used in this study covers 334 target sequences comprising allelic variants of approximately 185 distinct genes that include species markers, antimicrobial resistance genes, exotoxins, and genes encoding microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs) of the host, as well as the SCCmec cassette, capsule, and agr group typing markers (9, 10).

RESULTS

Case reports and clinical characteristics. (i) Case 1.

A 67-year-old man, with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), was admitted to the hospital for elective surgery of gastric adenocarcinoma on 30 July 2006. On the eighth postoperative day, the patient presented with fever of unknown origin and two sets of blood cultures were drawn from a central venous catheter (CVC) and peripheral vein. Positive cultures yielded Gram-positive cocci in pairs and tetrads. The patient was treated empirically with vancomycin, and the CVC was removed. A transesophageal echocardiogram revealed vegetations on the mitral valves with abscess formation. The patient was diagnosed with mitral endocarditis and catheter-associated bacteremia, and rifampin and levofloxacin were added to the treatment. Positive blood samples were subcultured on sheep blood agar at 35°C in an aerobic atmosphere and on chocolate agar at 35°C with 5% CO2. Aerobically grown culture plates examined the next day showed nonpigmented, nonhemolytic microcolonies of a diameter of approximately 0.1 mm. However, in an environment of 5% CO2, the colonies grew with typical staphylococcal morphology. Both aerobic and microaerophilic isolates were identified as S. aureus and were resistant to methicillin, levofloxacin, erythromycin, and clindamycin. On the 13th day, a mitral valve replacement was performed, but the patient finally died 15 days after cardiac surgery.

(ii) Case 2.

A 59-year-old man, with a history of arterial hypertension and obesity, was admitted to the surgery department with a recent diagnosis of unresectable colorectal cancer on 17 July 2006. He had surgery 2 days later for terminal colostomy but presented with signs of necrosis of the stoma. The patient needed surgical reintervention for a new colostomy 6 days later. On the 34th day, his abdominal wound exhibited seropurulent secretion, and he started antimicrobial treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and metronidazole. Culture of the abdominal wound was performed 3 days later. After 48 h of aerobic incubation at 37°C, the primary isolates on sheep blood agar showed several colony morphologies, although nonpigmented, nonhemolytic, pinpoint colonies predominated. Gram staining of different colonies showed that they were all Gram-positive cocci and all exhibited catalase activity. Subculture of pinpoint colonies onto sheep blood agar in 5% CO2 led to reversion to a pigmented hemolytic colony morphology, while subculture in an aerobic atmosphere continued to yield the same atypical microcolonies. The isolates were identified as S. aureus and were resistant to methicillin, levofloxacin, erythromycin, and clindamycin.

Both the above patients were hospitalized in the same ward in adjacent rooms when they were infected. MRSA isolates from the two patients had identical PFGE patterns (Fig. 1), and further epidemiological investigation showed that case 2 could be the index case for MRSA transmission to case 1 through the health care workers attending the ward.

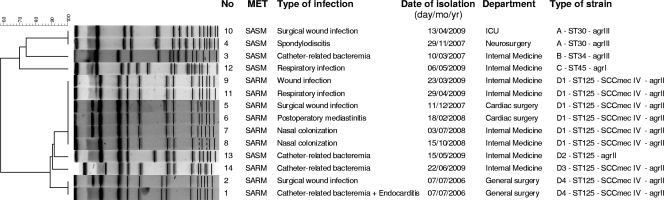

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram based on PFGE patterns of CO2-dependent small-colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus. ICU, intensive care unit; MET, methicillin; SASM, S. aureus susceptible to methicillin; SARM, S. aureus resistant to methicillin. The type of strain was defined by PFGE, ST, SCCmec, and agr typing.

After these two cases, CO2-dependent S. aureus SCV isolates were obtained from another 12 patients. Among the total of 14 cases, the mean age of the patients was 66.2 years (standard deviation [SD], 17.69) and nine (64.3%) were male. Twelve cases (85.7%) were considered hospital-associated infections, and seven (50%) had previously received antibiotics. Twelve patients (85.7%) were considered to have clinical infections while two had only nasal colonization. Two patients died of causes directly related to their CO2-dependent S. aureus infections. Selected clinical characteristics of the patients with CO2-dependent S. aureus SCVs are shown in Fig. 1.

Microbiological characteristics of CO2-dependent S aureus SCVs.

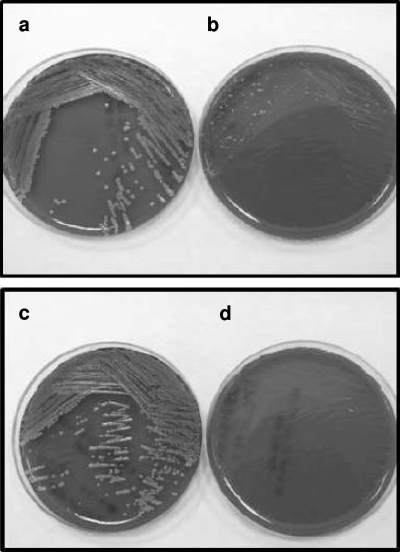

During the study period 14 clinical isolates of S. aureus SCVs were obtained, the microbiological characteristics of which are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2. Primary isolates of CO2-dependent S. aureus after incubation for 24 h in an aerobic atmosphere showed some variability in appearance. In five cases (35.7%), cultures exhibited a very scant growth of only microcolonies, while in another six cases (42.9%) cultures had a heterogeneous appearance with microcolonies surrounding others of normal phenotype. In three cases (21.4%) there was no growth under aerobic conditions. All SCVs reverted to a normal phenotype after incubation in 5% CO2 for 18 h. All SCVs grew anaerobically. The stability of the SCV phenotype was low, and all SCVs reverted to a normal morphology after 3 to 6 subcultures under aerobic conditions. With regard to coagulase activity, four isolates were negative at 4 h, but all were positive at 18 h of incubation. Three isolates were misidentified, two as Staphylococcus epidermidis and one as Micrococcus spp. All isolates were identified as S. aureus by DNA sequence analysis. The susceptibility to methicillin was also correctly reported by broth microdilution and by diffusion disk agar (with the exception of one SCV isolate) as evidenced by the presence of the mecA gene in all isolates identified as MRSA.

TABLE 1.

Microbiological characteristics of CO2-dependent Staphylococcus aureus

| Isolate no. | Growth and appearance of the culturea | Hemolysis (TSBA)a | Pigmenta | % of SCVs isolated in primary culture | Stability of SCVs on cultureb | Reversion to normal morphology when supplemented with: |

Coagulase reactionc |

Wider identification and methicillin resistance (% probability) | Susceptibility to methicillin by diffusion disks (mm and category)d |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | Hemin | Menadione | Thymidine | 2 h | 4 h | 18 h | Oxacillin | Cefoxitin | |||||||

| 1 | 6/10, heterogeneous | Yes, few colonies | Yes, few colonies | 70 | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Pos | Pos | Pos | MRSA (99.9) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) |

| 2 | 1/10, homogeneous | No | No | 100 | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Neg | Neg | Pos | MRSA (99.9) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) |

| 3 | 3/10, heterogeneous | No | No | 80 | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Pos | Pos | Pos | MSSA (99.7) | No growth | No growth |

| 4 | 2/10, heterogeneous | No | No | 80 | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Pos | Pos | Pos | MSSA (99.8) | 22 (S) | 29 (S) |

| 5 | 1/10, homogeneous | No | No | 100 | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Neg | Neg | Pos | MRSA (99.9) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) |

| 6 | 3/10, heterogeneous | Yes, few colonies | Yes, few colonies | 70 | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Pos | Pos | Pos | MRSA (99.8) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) |

| 7 | No growth | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Neg | Pos | Pos | Micrococcus sp. (94.8) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | |||

| 8 | 1/10, homogeneous | No | No | 100 | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Neg | Pos | Pos | MRSA (99.9) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) |

| 9 | 1/10, homogeneous | No | No | 100 | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Neg | Pos | Pos | MRSA (99.3) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) |

| 10 | No growth | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Neg | Neg | Pos | S. epidermidis (99.8) | 26 (S) | 29 (S) | |||

| 11 | No growth | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Neg | Pos | Pos | S. epidermidis (99.8) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) | |||

| 12 | 1/10, homogeneous | No | No | 100 | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Neg | Pos | Pos | MSSA (99.9) | 27 (S) | 29 (S) |

| 13 | 2/10, heterogeneous | No | Yes, few colonies | 70 | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Pos | Pos | Pos | MSSA (99.9) | 23 (S) | 25 (S) |

| 14 | 7/10, heterogeneous | Yes | Yes | 50 | Low | Yes | No | No | No | Neg | Neg | Pos | MRSA (99.9) | 0 (R) | 0 (R) |

Characteristics of growth in Trypticase soy blood agar (TSBA) after 24 h of incubation at 35°C in an aerobic atmosphere. Growth is scored as 0 to 10, with 10 being growth of the culture on TSBA at 35°C in 5% CO2.

After 3 to 6 subcultures, the SCVs reverted to a normal phenotype.

Pos, positive; Neg, negative.

R, resistant; S, susceptible.

FIG. 2.

Blood agar plates of two pairs of Staphylococcus aureus isolates (plates a and b and plates c and d) that show the normal (a and c) and the small-colony variant (b and d) phenotypes.

Molecular characteristics of CO2-dependent S. aureus SCVs.

In order to determine if a specific clone of SCV S. aureus was being disseminated in our hospital, the 14 isolates that we obtained were subjected to SmaI-PFGE and MLST. PFGE typing showed that the 14 isolates were distributed into 4 PFGE types that were arbitrarily designated A, B, C, and D, with 4 related subtypes within D (D1 to D4). The characterization of each isolate by MLST and SCCmec typing (for MRSA isolates) demonstrated that they belonged to 4 different STs: ST125-SCCmec IV (9 MRSA isolates and 1 methicillin-susceptible S. aureus [MSSA] isolate), ST30 (2 MSSA isolates), ST34 (1 MSSA isolate), and ST45 (1 MSSA isolate) (Fig. 1).

In order to investigate whether there were differences between the genetic composition of CO2-dependent S. aureus and that of those strains that exhibit the normal phenotype, we performed microarray hybridization analysis. The 14 CO2-dependent isolates and 20 S. aureus isolates with normal phenotype and which belonged to the same STs were analyzed to identify antibiotic resistance determinants and characterize the presence or absence of genes encoding a variety of different virulence factors (Table 2 ). Among the genetic markers analyzed, none were present in all isolates with the normal phenotype that were not also present in the CO2-dependent S aureus isolates and vice versa. All isolates, independent of phenotype, had in common the enterotoxin gene cluster egc (seg, sei, sem, sen, seo, and seu); α-hemolysin; δ-hemolysin; biofilm genes icaA, icaC, and icaD; several MSCRAMM genes (clfA, clfB, ebh, eno, fib, ebpS, sdrC, and vw); and the isaB gene. However, 8 of 10 clinical isolates of CO2-dependent S. aureus SCVs belonging to ST125 more frequently had a full-length (untruncated) version of the hemolysin gene compared with 0/8 with normal phenotype. Furthermore, these CO2-dependent isolates were all negative for genes encoding entA, sak, chp, and scn, while seven of the isolates with normal phenotype were positive for these genes and one was positive for sak and scn. Another difference was that only 1 of 10 CO2-dependent isolates had the β-lactamase operon (blaZ, blaI, and blaR), while this operon was present in 6 of 8 isolates with normal morphological phenotype (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Antibiotic resistance determinants and virulence factors in Staphylococcus aureus with SCVs and normal phenotype

| Gene category and name | Gene product or function | Result for MLST sequence type and auxotrophya |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST125 |

ST30 |

ST34 |

ST45 |

||||||

| CO2 (n = 10) | No (n = 8) | CO2 (n = 2) | No (n = 6) | CO2 (n = 1) | No (n = 2) | CO2 (n = 1) | No (n = 4) | ||

| Resistance genotype | |||||||||

| mecA | Methicillin, oxacillin, and all beta-lactams, defining MRSA | 9/10 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| blaZIR | Beta-lactamase operon | 1/10 | 6/8 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ermC | Macrolide, lincosamide, streptogramin | 3/10 | 2/8 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| msrA | Macrolide | − | 5/8 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| mpbBM | Macrolide | − | 5/8 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| aadD | Aminoglycoside (tobramycin, neomycin) | 6/10 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| aphA | Aminoglycoside (kanamycin, neomycin) | − | 5/8 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| sat | Streptothricin | − | 5/8 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| tetK | Tetracycline | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| tetE efflux | Tetracycline efflux protein (putative transport protein) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| cat | Chloramphenicol | − | 1/8 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| fosB | Putative marker for fosfomycin, bleomycin | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| qacC | Unspecific efflux pump | − | 1/8 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Virulence genotype | |||||||||

| tst-1 | Toxic shock syndrome toxin | − | − | 1/2 | 4/6 | + | + | − | − |

| entA | Enterotoxin A | − | 7/8 | + | 2/6 | − | − | − | − |

| entA-320E | Enterotoxin A, allele from 320E | − | − | 1/2 | 1/6 | − | − | − | − |

| entA-N315 | Enterotoxin A, allele from N315 | − | 7/8 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| entC | Enterotoxin C | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| entH | Enterotoxin H | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| entL | Enterotoxin L | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| egc cluster | Enterotoxins from seg, sei, sem, sen, seo, and seu | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| PVL | Panton-Valentine leukocidin | − | − | − | 1/6 | − | − | − | − |

| lukF | γ-Hemolysin, component B | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| lukS | γ-Hemolysin, component C | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 1/4 |

| hlgA | γ-Hemolysin, component A | 7/10 | + | − | 2/6 | − | + | − | + |

| lukD | Leukocidin D component | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| lukE | Leukocidin E component | 8/10 | 7/8 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| lukX | Leukocidin/hemolysin toxin family protein | 6/10 | 7/8 | 1/2 | 4/6 | + | + | − | + |

| hla | α-Hemolysin (alpha toxin) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| hld | δ-Hemolysin | 9/10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| hlb | β-Hemolysin (phospholipase C) | 1/10 | 4/8 | − | 3/6 | − | + | − | − |

| Untruncated hlb | β-Hemolysin (phospholipase C/untruncated) | 8/10 | − | − | 2/6 | − | 1/2 | − | − |

| sak | Staphylokinase | − | + | + | 4/6 | + | 1/2 | + | + |

| chp | Chemotaxis inhibitory protein (CHIPS) | − | 7/8 | + | 3/6 | + | 1/2 | + | + |

| scn | Staphylococcal complement inhibitor | − | + | + | 4/6 | + | 1/2 | + | + |

| aur | Aureolysin | 9/10 | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| aur (other than 252) | Aureolysin, allele from other than MRSA252 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| aur-MRSA252 | Aureolysin, allele from MRSA252 | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| splA | Serine protease A | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| splB | Serine protease B | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| splE | Serine protease E | − | − | + | 4/6 | + | + | − | − |

| sspA | Glutamyl endopeptidase/V8 protease | 9/10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| sspB | Staphopain B | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| sspP | Staphopain A (staphylopain A) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Capsule/biofilm | |||||||||

| Capsule 5 | Capsule type 5 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Capsule 8 | Capsule type 8 | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| icaA, icaC, icaD | Intercellular adhesion proteins A and C, biofilm PIAb synthesis protein D | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| MSCRAMMs/adhesion factors | |||||||||

| bbp-all | Bone sialoprotein-binding protein | + | 7/8 | + | 5/6 | + | 1/2 | − | + |

| clfA-all | Clumping factor A | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| cna | Collagen-binding adhesin | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| ebh-all | Cell wall-associated fibronectin-binding protein | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Gene category and name | Protein | Result for MLST sequence type and auxotrophya |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST125 |

ST30 |

ST34 |

ST45 |

||||||

| CO2 (n = 10) | No (n = 8) | CO2 (n = 2) | No (n = 6) | CO2 (n = 1) | No (n = 2) | CO2 (n = 1) | No (n = 4) | ||

| eno | Enolase, phosphopyruvate hydratase | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| fib | Fibrinogen-binding protein | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| fib-MRSA252 | Fibrinogen-binding protein, allele from MRSA252 | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | 3/4 |

| ebpS | Cell wall-associated fibronectin-binding protein | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| fnbA-all | Fibronectin-binding protein A | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| fnbB-COL+Mu50+MW2 | Fibronectin-binding protein B, allele from COL/Mu50/MW2 | + | + | − | 1/6 | − | − | + | + |

| fnbB-Mu50 | Fibronectin-binding protein B, allele from Mu50 | + | + | − | 1/6 | − | − | − | + |

| map | Major histocompatibility complex class II analog protein | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| sdrC-all | Ser-Asp-rich fibrinogen-binding, bone sialoprotein-binding protein C | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| sdrD-COL+MW2 | Ser-Asp-rich fibrinogen-binding, bone sialoprotein-binding protein D | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| sdrD-Mu50 | Ser-Asp-rich fibrinogen-binding, bone sialoprotein-binding protein D, allele from Mu50 | 8/10 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| sdrD-other | Ser-Asp-rich fibrinogen-binding, bone sialoprotein-binding protein D, allele from other | − | − | + | 4/6 | + | + | − | − |

| sdrD-other than 252 + 122 | Ser-Asp-rich fibrinogen-binding, bone sialoprotein-binding protein D, allele from other than MRSA252/RF122 | + | + | + | 5/6 | + | + | − | + |

| vwb-all | von Willebrand factor-binding protein | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| vwb-MRSA252 | von Willebrand factor-binding protein, allele from MRSA252 | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| vwb-Mu50 | von Willebrand factor-binding protein, allele from MU50 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| sasG | S. aureus surface protein G | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Immunoevasion and miscellaneous | |||||||||

| isaB | Immunodominant antigen B | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| mprF | Probable lysylphosphatidylglycerol synthetase (defensin resistance) | 7/10 | + | 1/2 | 5/6 | + | + | − | − |

| isdA | Heme/transferrin-binding protein | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| lmrP | Putative transporter protein | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

In cases where the gene was not present in all isolates, data are shown as number of isolates with the gene present/total number of isolates.

PIA, polysaccharide intercellular adhesin.

Among CO2-dependent S. aureus isolates, besides the variability in PFGE patterns, STs, and agr groups (I, II, and III), we also identified variability (presence or absence) in the antibiotic determinant genes (mecA and blaZIR), β-hemolysin, enterotoxin A, and the genes encoding staphylokinase (sak), chemotaxis inhibitory protein (chp), and staphylococcal complement inhibitor (scn). Overall, the CO2-dependent isolates presented several differences in their array hybridization patterns, with the exception of isolates 1 and 2, which exhibited identical patterns.

DISCUSSION

We have recently observed isolates of S. aureus growing as dwarf colonies or showing heterogenous appearance in culture, with satellite growth of microcolonies around others of apparently normal phenotype. These clinical isolates comply with all the requisites to be defined as SCVs of S. aureus. We demonstrated that 14/14 (100%) of the clinical isolates that we recovered over a 3-year period which exhibited this phenotype were CO2 auxotrophs. Previous studies have demonstrated that SCVs are most frequently associated with menadione and thiamine deficiency, and only occasionally have they been reported to exhibit CO2 dependency (14). The stability of the microcolony phenotype in our isolates was low, and all reverted to a normal colony morphology after several subcultures. This suggests that the exhibition of this phenotype is governed at the level of gene expression, rather than by the presence or absence of one or more specific genes.

The real incidence of infection/colonization by CO2-dependent S. aureus is unknown. While our data suggest that the prevalence of these strains is low, with only 14 isolates in a period of almost 3 years, this may represent an underestimation of the true rate of new infections because not all cultures are incubated in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. CO2 SCVs are characterized by fastidious growth characteristics and an atypical, small-colony morphology (nonpigmented and nonhemolytic colonies) that may be entirely overlooked in mixed cultures. When they are recognized, SCVs may still be misidentified as coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, and susceptibility test results can be difficult to interpret. To reduce the potential of missing these isolates, it is important to observe the microbiological characteristics of colonies on plates incubated in a CO2 atmosphere and to extend conventional cultures to at least 72 h. Nasal samples used to detect MRSA colonization are usually inoculated on mannitol-salt agar and incubated in an aerobic atmosphere for 48 h. Therefore, colonization with CO2-dependent S. aureus can be missed if incubation is not extended and plates are not supplemented with CO2. We recommend incubating at least one agar plate in a CO2 atmosphere for all samples with suspicion of S. aureus. Some authors also suggest using Columbia blood agar and chromogenic agar media for recovery and identification of S. aureus SCV auxotrophs for thymidine (8). On the other hand, SCVs also present a challenge with regard to susceptibility testing. Errors can occur when these variants are resistant to oxacillin and are tested using disk diffusion methods (14). In these cases, sometimes it is necessary to increase the inoculum of bacteria and to detect the mecA gene by molecular methods (14). SCV isolates may also be obtained from patients with a variety of clinical manifestations, including severe infections such as catheter-related bacteremia, endocarditis, and surgical or respiratory infections in addition to nasal colonization.

In the present study, we identified two patients who were admitted to the same clinical ward and who were infected with the same strain of SCV S. aureus, as demonstrated by MLST, PFGE, and DNA microarray analysis. The secondary case developed catheter-related bacteremia complicated with endocarditis, and the patient finally died in spite of treatment with vancomycin and rifampin and valve replacement. This was an example of nosocomial transmission with important clinical consequences. Although several studies using animal models have indicated that S. aureus SCVs might be less virulent than strains with the normal phenotype, as determined by measurement of lethal doses and fatality rates, under the right conditions, SCVs can persist for long periods, thereby facilitating recurrent infections and clinical complications (14). Some authors propose that the formation of SCVs is a strategy used by the bacterium to resist antibiotic therapy by becoming a facultative intracellular pathogen (25). Compared to typical S. aureus strains, SCVs show increased uptake by host cells, as well as resistance to and reduced stimulation of intracellular host defenses (14, 18).

In order to gain insights into the genetic makeup of CO2-dependent S. aureus SCVs, we first investigated the clonality of these isolates. We observed that SCV isolates were primarily nonclonal in origin, belonging to different sequence types (ST125, ST30, ST34, and ST45). Notably, clones belonging to these STs and exhibiting a normal phenotype were also circulating in our community and hospital. We also studied the antibiotic resistance and virulence determinants of these isolates by using an array hybridization assay. No common pattern of genetic markers was evident, and we found remarkable variability with regard to antibiotic resistance markers, agr groups, SCCmec types, exotoxin genes, capsule types, and MSCRAMM genes. With few exceptions, isolates that belonged to the same ST shared almost the same array hybridization pattern, independent of the phenotype (SCV or not). We found in all SCV isolates belonging to ST125 that the genes encoding entA, sak, chp, and scn were absent, while these genes were present in most isolates with normal phenotype. What accounts for the differences is the fact that these genes are carried by β-hemolysin-converting bacteriophages, which leads to the disruption of the β-hemolysin (22). Probably, any S. aureus strain belonging to any ST can develop SCV CO2 auxotrophy, although we do not know what alterations in bacterial metabolism may cause this type of variant or the genetic mechanism for reversion to a rapidly growing form. In 1970 investigators who studied two strains of CO2-dependent microcolony variants of S. aureus by electron microscopy showed that the cell walls of the isolates when grown in air were thick and irregular (19). In contrast, in a CO2 atmosphere, their ultrastructure appeared to be that of normal staphylococci.

Our study confirms the importance of CO2-dependent SCVs of S. aureus as significant pathogens in a variety of clinical presentations, ranging from severe infections such as catheter-related bacteremia, endocarditis, and surgical or respiratory infection to nasal colonization. Clinical microbiologists must be made aware of this kind of auxotrophy because of the difficulties in isolating these variants by using routine laboratory methods. Nevertheless, further studies will be necessary to understand the true prevalence of CO2 auxotrophs of S aureus, the factors which select this phenotype in the host, and the genetic basis of this type of auxotrophy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tobin Hellyer for reviewing the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI RD06/0008/0011) and by PI07/90239 and PI081520 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acar, J. F., F. W. Goldstein, and P. Lagrange. 1978. Human infections caused by thiamine- or menadione-requiring Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 8:142-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Besier, S., C. Smaczny, C. von Mallinckrodt, A. Krahl, H. Ackermann, V. Brade, and T. A. Wichelhaus. 2007. Prevalence and clinical significance of Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variants in cystic fibrosis lung disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:168-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantón, R., M. Perez-Vazquez, A. Oliver, B. Sánchez del Saz, M. O. Gutierrez, M. Martín-Ferrer, and F. Baquero. 2000. Evaluation of the Wider system, a new computer-assisted image-processing device for bacterial identification and susceptibility testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1339-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaves, F., J. García-Martínez, S. de Miguel, F. Sanz, and J. R. Otero. 2005. Epidemiology and clonality of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus causing bacteremia in a tertiary-care hospital in Spain. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 26:150-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2006. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 16th informational supplement M100-S16. CLSI, Wayne, PA.

- 6.Enright, M. C., N. P. Day, C. E. Davies, S. J. Peacock, and B. G. Spratt. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1008-1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahl, B., M. Herrmann, A. S. Everding, H. G. Koch, K. Becker, E. Harms, R. A. Proctor, and G. Peters. 1998. Persistent infection with small colony variant strains of Staphylococcus aureus in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1023-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kipp, F., B. C. Kahl, K. Becker, E. J. Baron, R. A. Proctor, G. Peters, and C. von Eiff. 2005. Evaluation of two chromogenic agar media for recovery and identification of Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variants. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1956-1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monecke, S., B. Berger-Bächi, G. Coombs, A. Holmes, I. Kay, A. Kearns, H.-J. Linde, F. O'Brien, P. Slickers, and R. Ehricht. 2007. Comparative genomics and DNA array-based genotyping of pandemic Staphylococcus aureus strains encoding Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:236-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monecke, S., P. Slickers, and R. Ehricht. 2008. Assignment of Staphylococcus aureus isolates to clonal complexes based on microarray analysis and pattern recognition. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 53:237-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Musher, D. M., R. E. Baughn, G. B. Templeton, and J. N. Minuth. 1977. Emergence of variant forms of Staphylococcus aureus after exposure to gentamicin and infectivity of the variants in experimental animals. J. Infect. Dis. 136:360-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliveira, D. C., and H. De Lencastre. 2002. Multiplex PCR strategy for rapid identification of structural types and variants of the mec element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2155-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Proctor, R. A., P. van Langevelde, M. Kristjansson, J. N. Maslow, and R. D. Arbeit. 1995. Persistent and relapsing infections associated with small-colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Proctor, R. A., C. von Eiff, B. C. Kahl, K. Becker, P. McNamara, M. Herrmann, and G. Peters. 2006. Small colony variants: a pathogenic form of bacteria that facilitates persistent and recurrent infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:295-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proctor, R. A., and G. Peters. 1998. Small colony variants in staphylococcal infections: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:419-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahman, M. 1977. Carbon dioxide-dependent Staphylococcus aureus from abscess. Br. Med. J. 2(6082):319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seifert, H., H. Wisplinghoff, P. Schnabel, and C. von Eiff. 2003. Small colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus and pacemaker-related infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:1316-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sendi, P., and R. A. Proctor. 2008. Staphylococcus aureus as an intracellular pathogen: the role of small colony variants. Trends Microbiol. 17:54-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slifkin, M., L. P. Merkow, S. A. Kreuzberger, C. Engwall, and M. Pardo. 1971. Characterization of CO2 dependent microcolony variants of Staphylococcus aureus. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 56:584-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spagna, V. A., R. J. Fass, R. B. Prior, and T. G. Slama. 1978. Report of a case of bacterial sepsis caused by a naturally occurring variant form of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 138:277-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spink, W. W., K. Osterberg, and J. Finstad. 1962. Human endocarditis due to a strain of CO2-dependent penicillin-resistant staphylococcus producing dwarf colonies. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 59:613-619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Wamel, W. J., S. H. Rooijakkers, M. Ruyken, K. P. van Kessel, and J. A. van Strijp. 2006. The innate immune modulators staphylococcal complement inhibitor and chemotaxis inhibitory protein of Staphylococcus aureus are located on beta-hemolysin-converting bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 188:1310-1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Eiff, C., D. Bettin, R. A. Proctor, B. Rolauffs, N. Lindner, W. Winkelmann, and G. Peters. 1997. Recovery of small colony variants of Staphylococcus aureus following gentamicin bead placement for osteomyelitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 25:1250-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Eiff, C., G. Peters, and K. Becker. 2006. The small colony variant (SCV) concept—the role of staphylococcal SCVs in persistent infections. Injury 37:S26-S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Eiff, C. 2008. Staphylococcus aureus small colony variants: a challenge to microbiologists and clinicians. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 31:507-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]