Abstract

Multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (MLVA) was performed with 292 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates previously characterized by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, multilocus sequence typing, and staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec typing. Quantitative correspondence analyses showed the best correlation between data when an ≥80% cutoff was applied to MLVA. We confirmed the validity of MLVA for identification of related strains in a polyclonal MRSA population.

The first methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolate was detected in 1961 (8). Since then, MRSA has become one of the most worrisome pathogens worldwide. Many efforts to design an ideal method to type these bacteria and to control their dissemination have been employed (4). Up to now, the gold standard for short-term epidemiological surveillance of S. aureus has been pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (5, 6, 7). However, this method is demanding and time-consuming and needs expensive reagents. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) is the ideal method for long-term epidemiological studies, but its routine application is very unfeasible in clinical laboratories. In 2003, a new method for typing S. aureus strains, multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (MLVA), was applied (18). This technique consists of simultaneous amplification of variable-number tandem repeats of different genes. Several works have tried to determine if MLVA provides enough information to be performed routinely instead of PFGE or MLST in clinical microbiology laboratories (20).

Our aim was to determine if MLVA could predict MRSA clones present in the Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria (HUNSC) that were previously characterized by PFGE, MLST, and staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing (reported here as PFGE/MLST-SCCmec type) (16) and to establish possible criteria of clustering MLVA patterns, looking for high concordance levels. This study expects to validate MLVA to introduce it as a routine typing method in the HUNSC.

The 292 MRSA isolates included in this study belonged to the clones included in Table 2. MLVA was performed as previously described (18) but slightly modified to obtain optimal results and to accelerate the process. The PCR mixture was prepared with 1× reaction buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 1.2 μM each of ClfA-F, ClfA-R, ClfB-F, ClfB-R, SdrCDE-F, and SdrCDE-R primers, 0.5 μM each of Spa-F and Spa-R primers, 1 μM each of Sspa-F and Sspa-R primers, and 0.05 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Bioline). Cycling conditions (MyCycler; Bio-Rad) were 94°C for 5 min, 20 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 58.2°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1.5 min, and finally 72°C for 5 min. To assess reproducibility, 10 randomly chosen isolates of different MLVA types were used for three independent MLVA experiments. The dendrogram obtained by Dice's coefficient with a 1% tolerance value was analyzed using three different cutoffs. Simpson's index of diversity, D (19), was employed to measure the discriminatory powers of MLVA and PFGE/MLST-SCCmec typing (9, 12), and concordance levels between these methods were quantified using two coefficients, adjusted Rand (AR) (11) and Wallace (W) (17, 22), as Carriço et al. suggested (2).

TABLE 2.

Classifications of different MRSA clones obtained by application of 80% and 70% cutoff criteria, indicating the MLVA types and subtypes

| CC | PFGE/MLST-SCCmec type, no. (%) of isolates | No. (name[s]) of PFGE subtypes at >80% cutoff | >80% cutoff |

>70% cutoff |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of MLVA types in CC | MLVA type | No. (name[s]) of MLVA subtypes | Total no. of MLVA types in CC | MLVA type | No. (name[s]) of MLVA subtypes | |||

| 8 | PFGE-A/ST247-IA, 58 (15.59) | 12 (A1 to A12) | 4 | b | 7 (b1 to b7) | 4 | c | 7 (c1 to c7) |

| PFGE-L/ST8-IVA, 1 (0.34) | 1 (L1) | ñ | 1 (ñ1) | i | 1 (i1) | |||

| PFGE-V/ST8-IV, 1 (0.34) | 1 (V1) | o | 1 (o1) | j | 1 (j1) | |||

| PFGE-O/ST239-III, 1 (0.34) | 1 (O1) | g | 1 (g1) | g | 1 (g1) | |||

| 30 | PFGE-B/ST36-II, 164 (55.41) | 9 (B1 to B9) | 2 | a | 8 (a1 to a8) | 1 | a | 9 (a1 to a9) |

| PFGE-F/ST30-IV, 1 (0.34) | 1 (F1) | h | 1 (h1) | |||||

| 5 | PFGE-C/ST125-IVA, 50 (16.89) | 3 (C1 to C3) | 6 | c, d, n | 4 (c1 to c4), 1 (d1), 1 (n1) | 2 | b | 6 (b1 to b3, b5, b6, b8) |

| PFGE-D/ST146-IVA, 8 (2.70) | 1 (D1) | c, d, k, m | 1 (c1), 1 (d1), 1 (k1), 1 (m1) | b, e | 3 (b1, b4, b7), 1 (e2) | |||

| PFGE-D/ST471-IV, 1 (0.34) | 1 (N1) | l | 1 (l1) | e | 1 (e3) | |||

| 22 | PFGE-E/ST22-IV, 5 (1.69) | 2 (E1, E2) | 1 | e | 1 (e1) | 1 | d | 1 (d1) |

| Unknown | PFGE-M/ST80-IV, 1 (0.34) | 1 (M1) | 1 | f | 1 (f1) | 1 | f | 1 (f1) |

| PFGE-U/ST88-IV, 1 (0.34) | 1 (U1) | 1 | i | 1 (i1) | 1 | h | 1 (h1) | |

| Total | 12a | 34 | 16 | 31 | 10 | 32 | ||

Total number of different PFGE/MLST-SCCmec types.

All 292 MRSA isolates were typeable by MLVA. Interestingly, it was possible to optimize the results by running the five pairs of primers in the same reaction, described as a difficult technique (20). Also, the PCRs were performed successfully from cellular suspensions without DNA extraction. The intralaboratory reproducibility of MLVA was very high (100%), as previously noted by other authors (13, 20).

By application of the previously established criterion in which two isolates with any different band were classified as two distinct MLVA types (18), MLVA produced 35 distinct patterns, showing a D value of 71.33% (range, 66.14 to 76.52%). Although PFGE showed a lower value, D of 68.47% (64.07 to 72.88%), the difference was not significant. The isolates were divided into 14 clusters (a to n), and 21 organisms had unique MLVA patterns (ñ to ah). The PFGE-A/ST247-IA, PFGE-B/ST36-II, PFGE-C/ST125-IVA, and PFGE-D/ST146-IVA clones were divided into different MLVA types. All of the PFGE-E/ST22-IV isolates were clustered together, and each sporadic MRSA clone corresponded with one MLVA type. Therefore, we are able to rule out relationships but not to establish them. The quantitative analyses showed low congruence values and even lower values when the PFGE subtypes were considered (Table 1). Tenover et al. obtained similar results with a visual analysis determining if MLVA could predict USA strain PFGE types. Then, they applied the >80% and >75% relatedness cutoff criteria (20). We tested other criteria and the >80% and >70% relatedness cutoffs, as previously proposed (13, 20).

TABLE 1.

Correlation between MLVA using 3 cutoff criteria and different methods for the identification of MRSA clonesa

| Alternate method(s) | Correlation established using MLVA with cutoff of: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One band |

>80% relatedness |

>70% relatedness |

||||

| AR (ratio) | W (%) | AR (ratio) | W (%) | AR (ratio) | W (%) | |

| PFGE type/MLST-SCCmec typing | 0.794 | 98.71 (97.93-99.45) | 0.976 | 98.29 (97.11-99.33) | 0.967 | 96.08 (93.35-98.08) |

| PFGE subtype/MLST-SCCmec typing | 0.644 | 69.21 (61.01-77.38) | 0.696 | 65.86 (58.51-73.12) | 0.688 | 64.62 (57.15-71.59) |

| PFGE type/MLST-SCCmec typing and CC determination | 0.794 | 98.71 (97.93-99.45) | 0.976 | 98.29 (97.11-99.33) | 0.967 | 96.08 (93.35-98.08) |

| PFGE subtype/MLST-SCCmec typing and CC determination | 0.644 | 69.21 (61.01-77.38) | 0.696 | 65.86 (58.51-73.12) | 0.688 | 64.62 (57.15-71.59) |

| CC determination | 0.765 | 100 | 0.957 | 100 | 0.986 | 100 |

Boldface type shows the values indicating the best cutoff criteria to detect MRSA clones previously identified by PFGE/MLST-SCCmec typing and to cluster isolates belonging to the same CC.

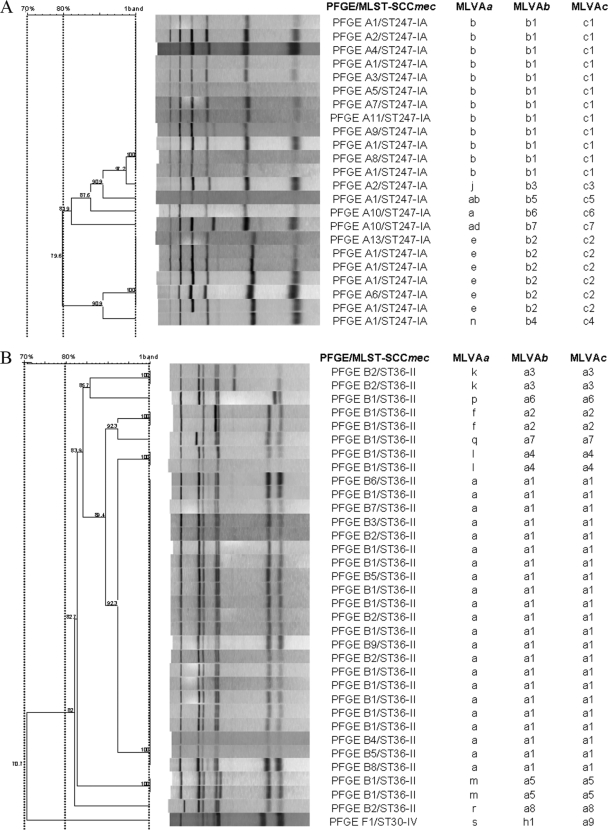

By use of the >80% relatedness cutoff, the number of MLVA types was reduced from 35 to 17, reducing the D value to 61.82% (57.00 to 66.04%). The 17 MLVA types included 5 clusters of >1 organism and 12 unique MLVA patterns (Table 2 ). The PFGE-A/ST247-IA, PFGE-B/ST36-II, and PFGE-E/ST22-IV clones corresponded with the MLVA types b, a, and e, respectively. Therefore, we were successful in grouping MRSA isolates to the same clone, although the distributions of the MLVA subtypes and the PFGE subtypes did not correspond. Subtype A1, the so-called Iberian clone, showed the same MLVA pattern as the other A subtypes (A2 to A13) (Fig. 1), and the same happened with subtypes B1 (Fig. 1) and E1, the so-called EMRSA-16 and EMRSA-15 clones, respectively. Therefore, MLVA could predict the PFGE/MLST-SCCmec types, but it could not distinguish the possible outbreaks of particular PFGE subtypes, being important above all in epidemic clones, such as the Iberian, EMRSA-16, and EMRSA-15 clones, present in our hospital. The quantitative analysis with and without PFGE subtype data demonstrated this observation (Table 1). On the other hand, the PFGE-C/ST125-IVA and PFGE-D/ST146-IVA clones were difficult to distinguish by MLVA, since both clones showed mixed MLVA types c and d (Table 2). These clustering differences of MLVA were observed by Tenover et al., applying the 80% and 75% cutoff criteria, with USA strain PFGE types. For example, USA100 isolates were clustered together in the same MLVA type, whereas USA800 isolates were separated into six different MLVA types. They suggested that the variability of the MLVA patterns may be strain dependent (20). Even so, congruence levels in our study upon application of this criterion were very high (Table 1). Therefore, MLVA typing could be a useful tool to localize and to follow the movement of these MRSA strains inside the hospital and, thus, to reduce the number of nosocomial infections, just as was described previously (3, 10).

FIG. 1.

Classification of the Iberian clone (PFGE-A1/ST247-IA) (A) and the EMRSA-16 clone (PFGE-B1/ST36-II) (B) into different MLVA types and subtypes depending on the cutoff criterion (a, 1 band; b, 80% relatedness; c, 70% relatedness) and relationships to the other PFGE subtypes. The gel images were analyzed with InfoQuest software, version 4.5 (Bio-Rad).

Use of the >70% relatedness cutoff reduced the number of MLVA types from 17 to 11, showing a D of 60.48% (55.92 to 65.04%). The 11 MLVA types included 5 clusters of >1 organism and 6 unique MLVA patterns (Table 2). As with the >80% cutoff, the PFGE-A/ST247-IA, PFGE-B/ST36-II, and PFGE-E/ST22-IV isolates each belonged to a different MLVA type (Fig. 1). However, by use of this less stringent criterion, the single isolate PFGE-F/ST30-IV was clustered together with the PFGE-B/ST36-II isolates, both belonging to clonal complex 30 (CC30). The PFGE-C/ST125-IVA and PFGE-D/ST146-IVA clones were mixed again, except one PFGE-D/ST146-IVA isolate that was clustered together with the PFGE-N/ST471-IV clone, both belonging to CC5 (Table 2). Therefore, the MLVA types represented MRSA isolates with different PFGE/MLST-SCCmec types, which was proven with the quantitative analysis (Table 1). Malachowa et al. determined a good correlation between MLVA and PFGE by applying a 70% cutoff for MLVA but a 75% cutoff for PFGE (13). Nevertheless, we do not agree with the change from an 80% cutoff for PFGE, since it is a justified and internationally accepted criterion (20). In that study, Malachowa et al. found that MLVA (70% cutoff) grouped isolates with the same CC, although with some exceptions. The exception in our study was CC8, where the different strains were not grouped together (Table 2). At a quantitative level, the values obtained in the analysis including the corresponding CCs together with PFGE/MLST-SCCmec types did not vary, while in the analysis comparing MLVA and CCs only, the AR and W values increased to 0.98 and 100%, respectively (Table 1).

Developing an efficient strategy to prevent the dissemination of MRSA clones and to provide optimal treatment for patients is of paramount importance. However, in many hospitals, the resources are not available for PFGE or MLST, techniques par excellence chosen in epidemiological studies. As a result, our aim has been to validate a method described as cheap, fast, and easy to use for analysis of hospital-acquired MRSA. Our efforts validate MLVA as a routine typing technique, reaching an agreement between the efficacy and the efficiency, as Trindade et al. suggested (21). Since the concordance levels between typing methods can vary depending on the collection of isolates, different studies of the correlation of MLVA and other techniques have led to various conclusions (15, 18, 20). In our analysis, MLVA could predict MRSA clones previously identified by PFGE/MLST-SCCmec typing (16), with the highest congruence between both methods achieved when we applied the 80% cutoff criterion. Also, the 70% cutoff criterion could be used to cluster isolates that belong to the same CC. Furthermore, MLVA has been described to provide a solid basis for the assignment of different genetic variants, which is useful information for epidemiological tracking (14).

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the ability of MLVA to distinguish among different MRSA reservoirs and other circulating MRSA strains in the HUNSC. The proven simplicity, low cost, and speed of MLVA enable the performance of routine checkups in patients, mainly via admission screening on surgical wards and in intensive care units, hampering the spread of these strains and therefore reducing the morbidity, mortality, and costs (1, 3, 10).

Acknowledgments

We thank Santiago Basaldua Lemarchand for his mathematical support and Joao Carriço for his helpful availability.

This work was supported partially by grant FIS06/0002 from the Spanish Health Ministry to S.M.-A. We thank the MAPFRE Foundation and COFARTE, a pharmaceutical company from Tenerife, for their founding contributions for the development of this study. B.R.-P. was supported partially by the MAPFRE Foundation and by COFARTE.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 June 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramson, M. A., and D. J. Sexton. 1999. Nosocomial methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus primary bacteremia: at what costs? Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 20:408-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carriço, J. A., C. Silva Costa, J. Melo-Cristino, F. R. Pinto, H. De Lencastre, J. S. Almeida, and M. Ramirez. 2006. Illustration of a common framework for relating multiple typing methods by application to macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2524-2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaberny, I. F., F. Schwab, S. Ziesing, S. Suerbaum, and P. Gastmeier. 2008. Impact of routine surgical ward and intensive care unit admission surveillance cultures on hospital-wide nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in a university hospital: an interrupted time-series analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:1422-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crisóstomo, M. I., H. Westh, A. Tomasz, M. Chung, D. C. Oliveira, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. The evolution of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: similarity of genetic backgrounds in historically early methicillin-susceptible and -resistant isolates and contemporary epidemic clones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:9865-9870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crossley, K., B. Landsman, and D. Zaske. 1979. An outbreak of infections caused by strains of Staphylococcus aureus resistant to methicillin and aminoglycosides. II. Epidemiologic studies. J. Infect. Dis. 139:280-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Helali, N., A. Carbonne, T. Naas, S. Kerneis, O. Fresco, Y. Giovangrandi, N. Fortineau, P. Nordmann, and P. Astagneau. 2005. Nosocomial outbreak of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in neonates: epidemiological investigation and control. J. Hosp. Infect. 61:130-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enright, M. C., D. A. Robinson, G. Randle, E. J. Feil, H. Grundmann, and B. Spratt. 2002. The evolutionary history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:7687-7692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eriksen, K. R., and I. Erichsen. 1963. Clinical occurrence of methicillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Ugeskr. Laeg. 125:1234-1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grundmann, H., S. Hori, and G. Tanner. 2001. Determining confidence intervals when measuring genetic diversity and the discriminatory abilities of typing methods for microorganisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4190-4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang, S. S., D. S. Yokoe, V. L. Hinrichsen, L. S. Spurchise, R. Datta, I. Miroshnik, and R. Platt. 2006. Impact of routine intensive care unit surveillance cultures and resultant barrier precautions on hospital-wide methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:971-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hubert, L., and P. Arabie. 1985. Comparing partitions. J. Classification 2:193-218. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunter, P. R., and M. A. Gaston. 1988. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:2465-2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malachowa, N., A. Sabat, M. Gniadkowski, J. Krzyszton-Russjan, J. Empel, J. Miedzobrodzki, K. Kosowska-Shick, P. C. Appelbaum, and W. Hryniewicz. 2005. Comparison of multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, spa typing and multilocus sequence typing for clonal characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3095-3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melles, D. C., L. Schouls, P. François, S. Herzig, H. A. Verbrugh, A. van Belkum, and J. Schrenzel. 2009. High-throughput typing of Staphylococcus aureus by amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) or multi-locus variable number of tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) reveals consistent strain relatedness. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28:39-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moser, S. A., M. J. Box, M. Patel, M. Amaya, R. Schelonka, and K. B. Waites. 2009. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus discriminates within U. S. A. pulsed-field gel electrophoresis types. J. Hosp. Infect. 71:333-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pérez-Roth, E., F. Lorenzo-Díaz, N. Batista, A. Moreno, and S. Méndez-Álvarez. 2004. Tracking methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones during a 5-year period (1998 to 2002) in a Spanish hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4649-4656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinto, F. R., J. Melo-Cristino, and M. Ramírez. 2008. A confidence interval for the Wallace coefficient of concordance and its application to microbial typing methods. PloS ONE 3:e3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sabat, A., J. Krzyszton-Russjan, W. Strzalka, R. Filipek, K. Kosowska, W. Hryniewicz, J. Travis, and J. Potempa. 2003. New method for typing Staphylococcus aureus strains: multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis of polymorphism and genetic relationships of clinical isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1801-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson, E. H. 1949. Measurement of species diversity. Nature 163:688. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tenover, F. C., R. R. Vaughn, L. K. McDougal, G. E. Fosheim, and J. E. McGowan, Jr. 2007. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat assay analysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:2215-2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trindade, P. A., J. A. McCulloch, G. A. Oliveira, and E. M. Mamizuka. 2003. Molecular techniques for MRSA typing: current issues and perspectives. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 7:32-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace, D. L. 1983. A method for comparing two hierarchical clusterings: comment. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 78:569-576. [Google Scholar]