Abstract

This study examined correlates of early adolescent alcohol and drug use in a community sample of 217 eighth-grade adolescents with behavior problems and from Hispanic/ Latino immigrant families. Structural equation modeling was used to examine relationships of multiple contexts (e.g., family, school, and peers) to alcohol and drug use. Results suggest that conduct disorder in youth with high levels of hyperactivity symptoms, poor school functioning, and peer alcohol and drug use was directly related to early adolescent alcohol and drug use. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder with comorbid conduct disorder and family functioning was indirectly related to early alcohol and drug use through poor school functioning and through peer alcohol and drug use. Results are discussed in terms of possible targets for interventions to prevent alcohol and drug use in Hispanic adolescents.

Rates of lifetime substance use nearly double between eighth grade and the end of high school (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2007). However, findings concerning risk for substance use in Hispanic youth have been inconsistent possibly because of variations in the populations sampled (e.g., school samples vs. community samples and variations across subgroups of Hispanics). Although some studies suggest that middle-school-aged Hispanic youth are at greater risk for substance use than non-Hispanic youth (e.g., Johnston et al., 2007), community studies have found the opposite in youth ages 12 to 17 (e.g., National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2005). Inconsistent findings may also be because of heterogeneity among the Hispanic population; when Hispanic subgroups (e.g., Cubans, Puerto Ricans) are analyzed separately, important variations emerge in rates of substance use (Delva et al., 2005; Wallace et al., 2002).

ATTENTION DEFICIT HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER AND CONDUCT DISORDER AND ALCOHOL AND DRUG USE

Psychiatric disorders particularly attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conduct disorder (CD) have been found to be associated with alcohol and drug use in youth (e.g., Barkley, Fischer, Smallish, & Fletcher, 2004; Fergusson, Horwood, & Ridder, 2007). However, findings from studies examining risk for substance use associated with ADHD have not been consistent, possibly because of differences in the way ADHD was measured (e.g., categorical vs. dimensional), the absence of controls for CD in some studies, and varying ages of youth. When a categorical approach is used to examine risk for alcohol and drug use associated with ADHD, some studies have found that comorbid CD greatly increases risk for alcohol and drug use among youth with ADHD (e.g., Barkley et al., 2005; Fergusson et al., 2007). This link remains even after CD is statistically controlled (e.g., King, Iacono, & McGue, 2004; Szabot et al., 2007). For example, Barkley and colleagues found that, compared to youth with ADHD without CD and to youth without any Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed. [DSM–IV]; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnoses, youth with both ADHD and comorbid CD were at increassed risk for substance use. In studies where youth with ADHD but not CD were compared to nondiagnosed youth, youth ADHD were not at increased risk for alcohol and drug use (Barkley et al., 2004). However, Molina and colleagues (2007) found that adolescents with ADHD aged 15 to 17 years were at increased risk for alcohol use disorder symptoms, whereas no increased risk was found among younger adolescents. In light of these results, it is possible that age may moderate the link between ADHD and substance use.

When risk for substance use is examined by dividing ADHD into its two dimensions, hyperactivity/impulsivity and inattention, both dimensions have been found to be associated with alcohol and drug use. However, the role of CD in increasing these risks remains unclear. Some studies have found that the inattention and hyperactivity dimensions were both associated with drug use disorders after controlling for CD (Molina & Pelham, 2003; Szabot et al., 2007). However, other studies have failed to find an association between ADHD dimensions and alcohol and drug use after controlling for CD (e.g., Burke, Loeber, & Lahey, 2001; Molina, Smith, & Pelham, 1999).

ADHD AND CD AND ALCOHOL AND DRUG USE IN HISPANIC YOUTH

Although a large number of studies have examined the effects of ADHD on risk for substance use, these studies have generally not included large numbers of Hispanic adolescents. It is therefore unclear whether results from these studies generalize to Hispanic adolescents. Given that the Hispanic population is projected to triple in the next 50 years (Bergman, 2004), and given the comparatively high rates of CD and ADHD among Hispanic adolescents (Turner & Gil, 2002), examining risk for substance use in Hispanic adolescents with ADHD, with or without comorbid CD, is an important public health concern.

Family Risk Factors and Early Alcohol and Drug Use

In addition to examining risk for substance use associated with these diagnoses, it is important to identify possible contextual factors (e.g., family, peer, school) that may play important roles in the relationship between ADHD and early adolescent substance use. Family functioning has been found to be important with regard to adolescent substance use, particularly for Hispanic youth (Broman, Reckase, & Freedman-Doan, 2006; Sale et al., 2006) and for youth with ADHD and comorbid CD (Rey, Walter, Plapp, & Denshire, 2000). Among Hispanics (e.g., Mexican, Cuban, and Puerto Rican) in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, family functioning (e.g., parental warmth and family acceptance) was more protective against adolescent drug use for Hispanics than for African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites (Broman et al., 2006).

In contrast, poor family functioning has been found to increase risk for substance use indirectly through increasing risk for CD, for association with deviant peers, and for poor school functioning (e.g., Dishion, Nelson, & Bullock, 2004). For example, for youth both with and without ADHD, poor parental monitoring of peer activities increases risk for alcohol and drug use by increasing risk for affiliation with substance-using peers (Chilcoat & Breslau, 1999). Mothers of youth with ADHD have been found to report poorer family functioning than families of youth without ADHD (Gerdes & Hoza, 2006). Moreover, the same parenting problems that are associated with ADHD and comorbid CD (e.g., ineffective discipline, lack of maternal warmth and involvement; Pfiffner, McBurnett, Rathouz, & Judice, 2005) have also been found to increase risk for substance use in Hispanic youth (Barrera, Biglan, Ary, & Li, 2001). When family functioning of youth with ADHD and CD is compared to that of youth with ADHD but no CD, family functioning has been found to be more positive in youth in the no-CD group. Indeed, families of youth with both ADHD and CD are often characterized by low family cohesion, harsh discipline, inconsistent parenting, low parental monitoring, and high family conflict (e.g., Drabick, Gadow, & Sprafkin, 2006; Rey et al., 2000).

SCHOOL RISK FACTORS AND EARLY ALCOHOL AND DRUG USE

The school context is also crucial both for Hispanic youth, nearly 40% of whom do not complete high school (Bergman, 2007), and for youth with ADHD, who often experience considerable trouble in school (Barkley, Fischer, Smallish, & Fletcher, 2006). The school context includes environmental (e.g., curriculum, school norms), family (e.g., parental involvement in school), and child (e.g., academic functioning, school bonding) factors. Results from past research support the association of these factors with substance use. For example, school-level disapproval of substance use was found to be negatively associated with substance use in a large national sample of adolescents (Kumar, O’Malley, Johnston, Schulenberg, & Bachman, 2004). Similarly, child and family factors (e.g., academic functioning, school bonding, parental involvement in school) have been found to be negatively associated with adolescent alcohol and drug use (Barkley et al., 2006; Biederman et al., 2004). Results from studies with Hispanic youth suggest that school bonding and functioning (e.g., grades, quality of school work, and completion of school work) may be protective against substance use for Cuban and Latin American youth (Pilgrim, Schulenberg, O’Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 2006). As a result, the school context may be particularly important for Hispanic youth and for youth with ADHD, both with and without CD—and possibly especially important for Hispanic youth with ADHD. These school factors may operate by protecting adolescents against association with deviant peers and in turn protecting youth against substance use (Crosnoe, 2002).

Peer Risk Factors and Early Alcohol and Drug Use

For most adolescents, alcohol and drug use generally takes place within the context of the peer group (Fletcher, Darling, & Steinberg, 1995) and deviant peer group affiliation are considered the strongest and most proximal correlates of adolescent alcohol and drug use in youth with and without ADHD (e.g., Dishion et al., 2004; Marshal, Molina, & Pelham, 2003). Indeed, Marshal et al. found that, compared to adolescents without ADHD, adolescents with ADHD were more likely to associate with deviant peers and, in turn, were more likely to use alcohol and drugs. However, this study did not control for the effects of CD. In a subsequent study, Marshal and Molina (2006) controlled for the effect of CD and found that peer substance use mediated the relationship between ADHD and substance use for youth with elevated symptoms of either CD or oppositional defiant disorder, but not for youth without these comorbid diagnoses.

THE PRESENT STUDY

The literature just reviewed suggests that both Hispanic youth and youth with ADHD and comorbid CD often manifest increased risk for alcohol and drug use. Adolescents within both of these categories—Hispanic youth with ADHD and comorbid CD—might therefore be especially in need of preventive interventions. In ascertaining the risks for alcohol and drug use among Hispanic adolescents with ADHD, and in designing alcohol and drug abuse prevention interventions for this population, it may be important to consider multisystemic perspectives such as ecodevelopmental theory (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999) and the social ecology model (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, & Henry, 2000). These approaches propose that risk for problem behaviors, including alcohol and drug use, should be examined across multiple systems such as family, peers, and school.

Based on ecodevelopmental theory, we propose a network of relationships among multiple contexts, ADHD, CD, and early alcohol and drug use. We tested four hypotheses concerning associations of multiple contexts and of ADHD and CD to adolescent alcohol and drug use using a sample of Hispanic adolescents. First, we hypothesized that poor school functioning, ADHD + CD, and peer substance use would be directly related to alcohol and drug use. Second, we hypothesized that the relationship of family functioning to alcohol and drug use would be mediated by ADHD + CD, poor school functioning, and peer alcohol and drug use. Third, we hypothesized that ADHD + CD would be indirectly related to alcohol and drug use through poor school functioning and peer alcohol and drug use. Finally, we hypothesized that the hyperactivity and inattentive dimensions of ADHD would not be associated with alcohol and drug use with CD in the model, but the interaction of hyperactivity and CD would be associated with alcohol and drug use.

METHOD

Participants

The sample presented here consisted of 217 eighth-grade adolescents (63% male) with behavior problems and their parents (84% female) from Hispanic/Latino immigrant families. These families were participating in a randomized prevention trial, and data used in this study are from the baseline assessment (collected prior to randomization to condition).

All of the parents and 56% of the adolescents were born outside the United States. Immigrant adolescents and parents were largely from Honduras (27%), Cuba (21%), or Nicaragua (18%). The remainder of immigrant adolescents and their parents were born in other Central and South American countries. Among adolescents born outside the United States, 36.5% had been living in America for less than 3 years, 45.8% for between 3 and 10 years, and 17.7% for more than 10 years. The median annual family income was between $10,000 and $14,999.

Adolescents were categorized into one of three diagnostic subgroups (ADHD + CD, ADHD without CD, and no ADHD or CD). Youth in all three subgroups may have also been diagnosed with depression and/or anxiety disorders and/or other disorders. Within subgroups (ADHD + CD, ADHD without CD, and no ADHD or CD), 91%, 85%, and 84% also had an anxiety disorder, respectively. Furthermore, 36%, 62%, and 18% also had depression; 0%, 46%, and 40% also had oppositional defiant disorder; and 53%, 35%, and 33% also had other disorders.

Procedures

Participant recruitment

Adolescents and their families were recruited from three large, predominantly Hispanic middle schools located within a single urban low-income school district in Miami-Dade County, Florida. School counselors at each of the participating middle schools were asked to identify Hispanic eighth-grade students whom they believed had at least “mild problems” on at least one of three Revised Behavior Problem Checklist (Quay & Peterson, 1987) subscales: CD, Socialized Aggression, and Attention Problems. Because no prior consent had been obtained from the families at this point, school counselor did not complete forms or provide any information to project staff regarding potential participants. The school counselors gave these students letters to bring home to their parents describing the study. Parents that indicated interest in participating were contacted by study staff, who then scheduled screening and baseline assessment.

During screening, the parent and adolescent were asked to provide informed consent/assent. The screening included a check for inclusion/exclusion criteria and completion of the same three Revised Behavior Problem Checklist subscales. Only adolescents rated by their parents as 1 standard deviation or more above the nonclinical sample normed mean (see Quay & Peterson, 1987) on at least one of the three Revised Behavior Problem Checklist scales were included in the study. All participating adolescents were of Hispanic immigrant origin (at least one parent born in a Spanish speaking country in the Americas), were in the eighth grade at baseline, had an adult primary caregiver who was willing to participate in the study, and lived within the catchment areas of one of the three middle schools included in the study. Adolescents were excluded if (a) the family was planning to move out of the catchment areas of the three schools during the 1-year intervention period, or out of the south Florida area during the remaining 3 years of the study, (b) the adolescent did not assent to participate, or (c) scheduling conflicts prevented parents from participating in intervention sessions.

During recruitment 531 potential participants were identified. Of the 531, 306 either refused (n = 74 or 14%) or did not meet eligibility criteria (n = 232 or 44%). The remaining participants completed a baseline assessment. Eight participants had incomplete data across several measures and were not included in analyses.

Baseline assessments

Parent and adolescent assessments were conducted in the language of their choice (i.e., English and Spanish) using audio computer-assisted self-interviewing methodology (Turner, Rogers, Lindberg, Pleck, & Sonenstein, 1998). Each questionnaire item, along with the response scale, was read to the participant through a set of headphones while she or he sat in front of a laptop computer screen. The participant indicated her or his response by entering the appropriate response on the laptop, after which the system proceeded to the next item. Families were compensated $50 for completing the assessment and $30 for transportation.

Measures

Diagnostic assessment

Parent and adolescent reports on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) predictive scales (DISC-DPS: Lucas et al., 2001) were used to assess ADHD, CD, oppositional defiant disorder, and other DSM–IV Axis I disorders. The DPS consists of 108 parent-report items and 114 adolescent-report items. The DISC-DPS has established cutoffs, which have been found to be predictive of formal psychiatric diagnoses. In the study validating the DISC-DPS against formal psychiatric diagnoses, diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for ADHD ranged from 1.00 to .71 and .90 to .82, respectively (Lucas et al., 2001). Sensitivity and specificity for youth report of CD ranged from 1.00 to .80 and .99 and .76, respectively (Lucas et al., 2001). Additional details about the DISC-P can be found in Lucas et al. 2001.

Family context

Family functioning included 11 indicators (6 adolescent reported and 5 parent reported): parent involvement, discipline, positive parenting, relationship with child, effective communication, family cohesion, and parental monitoring. The Parenting Practices Scale (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Zelli, & Huesmann, 1996) was used to obtain reports of parental involvement (parent: 20 items, α = .82; adolescent: 17 items, α = .87), discipline (parent: 19 items, α = .62), and positive parenting (parent: 9 items, α = .78; adolescent: 9 items, α = .86) and relationship with child (adolescent: 15 items, α = .82). Internal consistency coefficients reported were estimated on the present dataset. The Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale (Barnes & Olson, 1982) was used to obtain parent and adolescent reports (20 items each) of effective communication (α = .77 and .87, respectively) The Family Relations Scale (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Zelli, & Huesmann, 1997) was used to obtain adolescent reports of family cohesion (6 items, α = .83). The Parent Relationship with Peer Group Scale (Pantin, 1996) was used to obtain adolescent (6 items, α = .83) and parent reports (5 items, α = .85) of parental monitoring attempts to actively supervise their adolescents and know their adolescents’ friends.

These measures of family functioning including measures of parental involvement, positive parenting, family cohesion, and effective communication have been found to correlate strongly with one another (adolescent: r = .46–.81; parent: r = .22–.56), to load significantly on a single family functioning construct and to predict, substance use, and conduct problems in other samples of Hispanic adolescents (Schwartz, Mason, Pantin, & Szapocznik, in press, 2008; Schwartz, Pantin, Prado, Sullivan, & Szapocznik, 2005). After controlling for demographic factors, scores on the Parent Relationship with Peer Group Scale have also been found to be significantly related to externalizing symptoms in a sample of middle-school-age Hispanic females (Coatsworth et al., 2002).

School functioning

School functioning was assessed via teacher (i.e., conduct, academic, and effort grades), parent (i.e., school functioning problems), and adolescent (i.e., school functioning problems and bonding) reports. In quarterly report cards, teachers rated the adolescent’s conduct, academic performance, and effort for each class in which the student was enrolled. Academic and conduct grades were measured on a 5-point scale (A=4, B=3, C=2, D=1, and F=0), whereas effort grades were measured on a 3-point scale (1 to 3, with 1 representing the best effort). Academic and conduct grades were reverse coded so that higher scores would reflect poorer functioning. Academic grades have been used in other studies and have been found to be correlated with substance use (Bryant, Schulenberg, O’Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 2003; Mason & Windle, 2001).

Adolescents report of school functioning problems and of bonding to school were gathered using five items from the Youth Self Report (Achenbach, Dumenci, & Rescorla, 2002) and the school bonding subscale (8 items, α = .86) from the People in My Life (Cook, Greenberg, & Kusche, 1995) bonds with school measure. On the Youth Self Report, adolescents responded on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true). The school bonding subscale assesses the extent to which the adolescent enjoys school and feels connected to classmates and teachers and was reverse coded so that higher scores would reflect less bonding to school. Scores on the School Bonding subscale have been found to be negatively associated with teacher rated behavior problems in other samples of preadolescent youth (Murray & Greenberg, 2000, 2001).

Parents reports of their adolescent’s school functioning were assessed using one item from the Revised Behavior Problem Checklist (Quay & Peterson, 1987). Parents indicated the extent to which their “child is truant from school”. Responses were rated on a 3-point scale ranging 0 (no problem), 1 (mild problem), and 2 (severe problem).

Peer context

Peer alcohol and drug use (13 items, α = .90) was measured using “adapted” substance use items from the Monitoring the Future Survey (Johnston et al., 2007). The substance use items were “adapted” by replacing “have you” with “how many of your friends have.” Adolescents were asked how many of their friends have ever used alcohol or any illegal drug in their lifetime. Response choices ranged from 1 (none of them) to 4 (all of them).

Alcohol and drug use

Adolescents’ own alcohol and drug use was measured using 14 items from the Monitoring the Future Survey (Johnston et al., 2007). Scores obtained using this survey have been found to be related to family, peer, and school variables in expected ways (Bryant et al., 2003). Adolescents were asked on how many occasions, if any, they had used alcohol, marijuana, or other illicit substances in their lifetime. For alcohol, adolescents responded on a 7-point Likert scale ranging 0 (never used alcohol), 1 (1–2 times), 2 (3–5 times), 3 (6–9 times), 4 (10–19 times), 5 (20–39 times), and 6 (40 or more). However, adolescents were asked to provide a number corresponding to the number of times they used marijuana and other illicit drug use. Because responses for alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drugs were on different scales (Likert scale vs. open ended), scores from marijuana use and other illicit drug use were recoded to match the scale for alcohol use and summed to arrive at a total score for alcohol and drug use. For example, if a youth answered that s=he had used marijuana 6 times, this was recoded to 3 (where a response of 3 represents 6–9 occasions of use). Substance use scores obtained using this survey have been found to be positively associated with school misbehavior (Bryant, Schulenberg, Bachman, O’Malley, & Johnston, 2000; Bryant et al., 2003) and with peer encouragement of misbehavior (Bryant et al., 2003) in national samples of adolescents.

RESULTS

Data Analytic Strategy

Given small sample size restrictions, we were not able to estimate a full structural equation model with latent constructs. As a result, we estimated the hypothesized path models (i.e., categorical ADHD and dimensional ADHD) with observed composite variables (i.e., factor scores) that were generated using confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) on each of the study constructs (Streiner, 2005). To arrive at a more parsimonious model and to increase degrees of freedom, we reduced the number of paths in the hypothesized models that were not significant at p < .20 (cf. Feaster et al., 2000). Mediational hypotheses were investigated by calculating the bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004) for each of the hypothesized indirect relationships. This method derives a point estimate and 95% an empirical confidence interval (CI) of the products of the pathways involved in the mediation and is more accurate and statistically powerful than more traditional methods of testing for mediation (MacKinnon et al., 2004). If the CI does not include zero, this suggests a significant mediated relationship at the .05 probability level. Finally, guidelines outlined by Holmbeck (2002) were used to examine interactions of ADHD dimensions (hyperactivity and inattention) and CD.

Model fit for the CFA and for the path models was evaluated primarily in terms of the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The chi-square statistic is reported but is not used in interpretation, given that it often indicates significant deviations even when these deviations are quite small (Kline, 2006). CFI values of .95 or greater, and RMSEA values of .06 or less, are indicative of good model fit, (Byrne, 2001). All models were estimated using Mplus release 4.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2007).

Descriptive Statistics and Data Preparation

Fourteen cases had a small amount of missing data. However, Mplus is able to handle the relatively modest amounts of missing data using full-information maximum likelihood estimation, which is appropriate as long as missingness can be assumed to be random (McKnight, McKnight, Sidani, & Figuredo, 2007). Variables that were not normally distributed were transformed by adding one to the total score and taking the natural log function. Correlations among all study variables are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| Family Adol |

Family Parent |

Poor School |

ADHD+CD | No ADHD or CD | Peer Use | Alc & Drug Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Adol | ||||||

| Family Parent | .20** | |||||

| Poor School | −.38*** | −.14* | ||||

| ADHD+CD | −.10 | −.19** | .36*** | |||

| No ADHD/or CD | .07 | .14* | −.16* | −.41*** | ||

| Peer Use | −.20** | .01 | .38*** | .19** | −.02 | |

| Alc & Drug Use | −.18** | −.03 | .44*** | .26*** | −.10 | .48*** |

Note. Family Adol = adolescent report of family functioning; Family Parent = parent report of family functioning; Poor School = poor school functioning; ADHD + CD = attention deficit=hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with comorbid conduct disorder (CD) compared to ADHD without CD; No ADHD or CD = diagnoses other than ADHD and CD compared to ADHD without CD; Peer Use = peer alcohol and drug use.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Three diagnostic subgroups (ADHD + CD, ADHD without CD, and no ADHD or CD) were created. Thirteen youth had CD but not ADHD and were excluded from categorical ADHD analyses because meaningful comparisons could not have been conducted with such a small group. Because prior research (e.g., Barkley et al., 2004) has identified important differences between youth with and without ADHD and between youth with ADHD + CD and with ADHD but without CD, two dummy variables (ADHD + CD and no ADHD or CD) were created and ADHD without CD was used as the reference group. In analyses using ADHD dimensions (i.e., hyperactivity and inattention) a count of symptoms in each ADHD dimension was used.

CFAs

CFAs were used to ascertain the feasibility of collapsing multiple indicators into composite variables. Reliability was calculated using the formula described by Fornell and Larcker (1981). Weighted factor scores were created based on the factor pattern coefficients within each CFA.

Consistent with extant literature on general-population samples (Tein, Roosa, & Michaels, 1994), adolescent and parent report of family functioning were not highly correlated (r = .08–.34) and did not pattern well onto one latent construct. As a result, separate models were estimated, adolescent: χ2 (16) = 26.46, p = .05; CFI = .98, RMSEA = .06, β ranged from −.56 to .79; parent: χ2 (3)= 1.27, p = .745; CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < .001, β ranged from .48 to .82. Reliability for adolescent and parent family functioning was .84 and .74, respectively.

Because the model with school functioning included categorical variables, weighted least square parameter estimates was used as the estimation method, χ2 (10) = 15.93, p = .10; CFI = .99, RMSEA = .05, β ranged from .28 to .88. Reliability was .80. Because the model with adolescent alcohol and drug use included count variables (number of times each substance was used), a poisson model with a maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors and a robust chi-square test statistic (MLR) was used. MLR does not provide chi-square, CFI, or RMSEA to evaluate model fit or standardized β weights.

Path Analytic Model

To test the study hypotheses, we estimated two path models. The first path model examined the relationships of ADHD (entered as a categorical variable as previously above), CD, family functioning, poor school functioning, and peer alcohol and drug use to early adolescent alcohol and drug use. For the second path model, dimensional ADHD (symptoms of hyperactivity and inattention, as previously described) was entered in place of the two dummy coded ADHD variables.

Categorical ADHD

The model provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2 (4) = 3.55, p = .47; CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < .001, and accounted for 5% of variance in ADHD + CD, 3% of variance in no ADHD or CD, 24% of the variance in poor school functioning, 17% of variance in peer alcohol and drug use, and 32% of variance in early adolescent alcohol and drug use. After trimming paths that were not significant at p < .20 (cf. Feaster et al., 2000), the resulting model also fit the data well, χ2 (11) = 5.92, p = .88; CFI= 1.00, RMSEA < .001 (see Figure 1). To explore the contextual relationships within the overall model, we examined the path coefficients for each set of hypothesized direct and indirect relationships. We summarize the results of these analyses next.

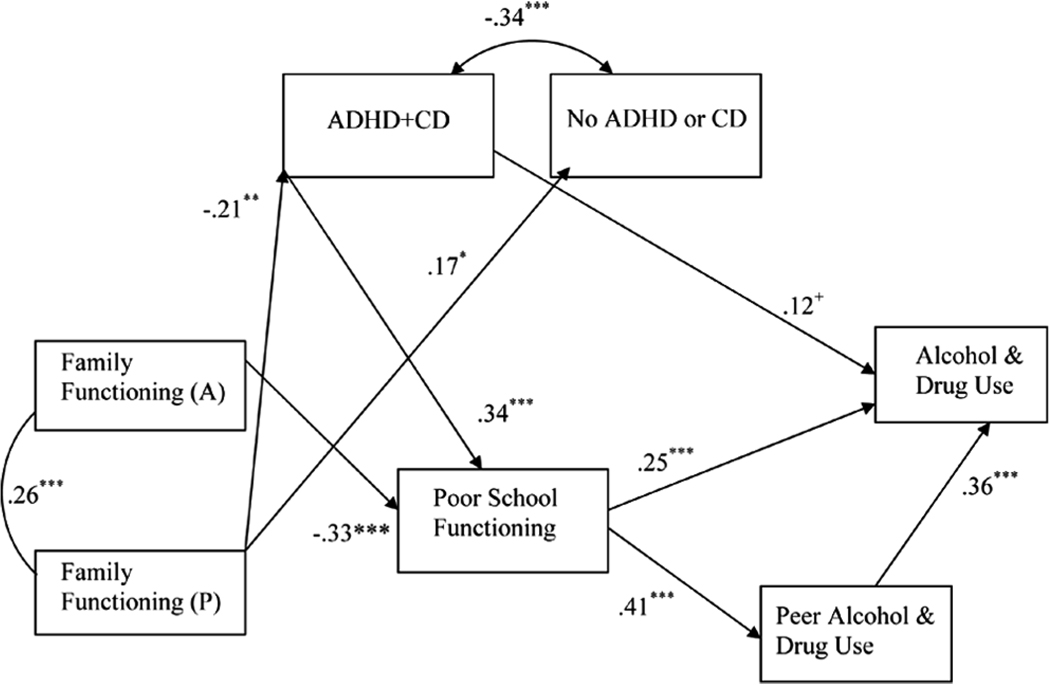

FIGURE 1.

Correlates of early substance use among Hispanic adolescents: ADHD and CD groups (N = 204). Note: Reference group for ADHD + CD and No ADHD or CD is ADHD without CD. 80% confidence intervals around the standardized parameter estimates were calculated, and none include zero. ADHD = attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder; CD = conduct disorder; A = adolescent report; P = parent report. +p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. Model fit: χ2 (11) = 5.92, p = .88; CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < .001.

In these analyses, only poor school functioning (β = .38, p < .001) and peer alcohol and drug use (β = .31, p < .001) were significantly directly related to early alcohol and drug use. Two indirect paths were tested for parent reports of family functioning but were not significant: through ADHD + CD, poor school functioning, and peer alcohol and drug use and through ADHD + CD and poor school functioning. Two indirect paths for adolescent reports of family functioning were tested and found to be significant: through poor school functioning and peer alcohol= drug use (point estimate: −0.01, 95% CI = −0.02 to −0.01) and through poor school functioning (point estimate: −0.02, 95% CI= −0.02 to −0.01). Also, two indirect paths from ADHD + CD were tested for mediation and found to be significant: through poor school functioning and peer alcohol and drug use (point estimate: 0.08, 95% CI = 0.03–0.14) and through poor school functioning (point estimate: 0.15, 95% CI = 0.04 to 0.25).

Dimensional ADHD

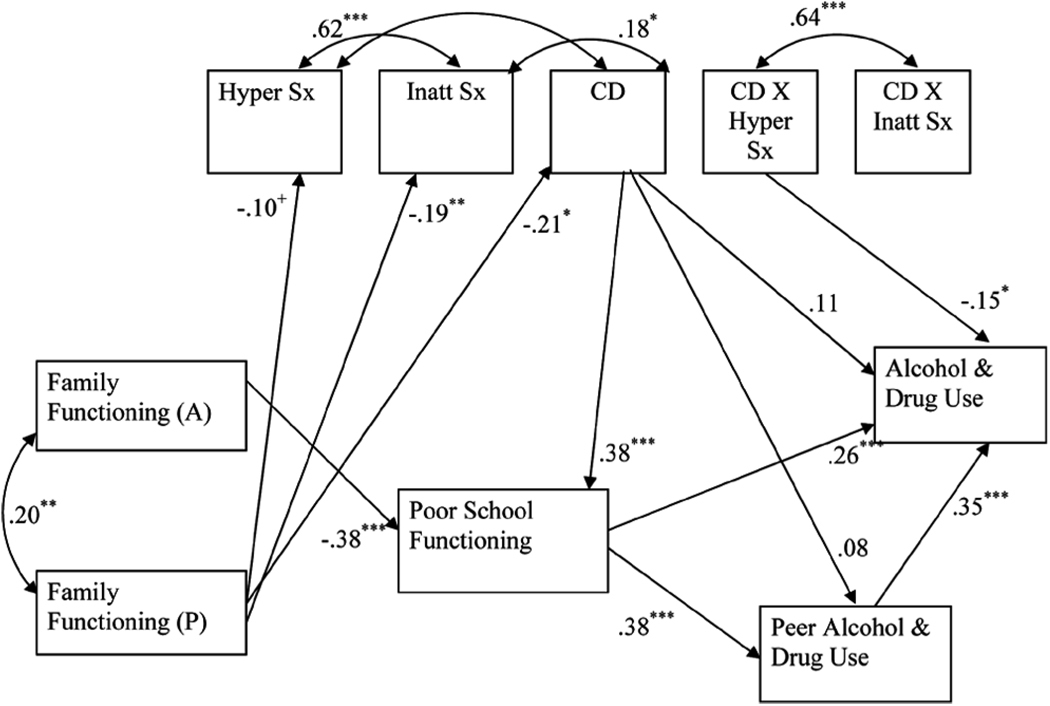

Next, we conducted parallel analyses with a dimensional measure of ADHD. The model provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2(6) = 11.34, p = .08; CFI = .96, RMSEA = .06, and accounted for 1% of the variance in hyperactivity/ impulsivity, 4% of the variance in inattention, 6% of the variance in CD, 30% of the variance in poor school functioning, 22% of the variance in peer alcohol and drug use, and 35% of the variance in early adolescent alcohol and drug use. After reducing the insignificant paths (p < .20), the resulting model also fit the data well, χ2(13) = 16.23, p = .24; CFI = .97, RMSEA = .03 (see Figure 1).

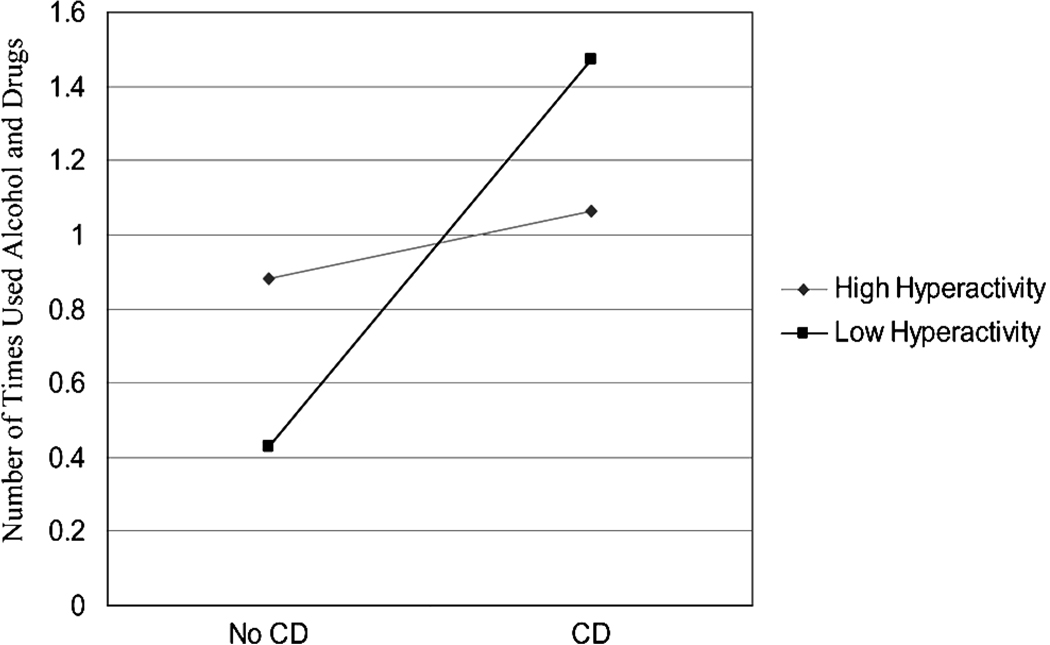

In this dimensional model, only the interaction of hyperactivity and CD was directly associated with adolescent alcohol and drug use (see Figure 2). Hyperactivity, inattention, CD, and the interaction of inattention and CD were not directly associated with adolescent alcohol and drug use. As recommended by Holmbeck (2002), we tested the slope of high (1 SD or more above the mean of hyperactivity symptoms) and low (1 SD or more below the mean of hyperactivity symptoms) hyperactivity symptoms to examine whether these slopes were significantly different from zero. We found that the slope of low hyper-activity symptoms was significant but the slope of high hyperactivity symptoms was not significant. We plotted these two slopes and present them in Figure 3 (Holmbeck, 2002). Results suggest that, among low-hyperactivity youth, CD is associated with increased alcohol and drug use. In contrast, among high-hyperactivity youth, there is little difference in alcohol and drug use among youth with CD versus without CD.

FIGURE 2.

Correlates of early substance use among Hispanic adolescents: ADHD inattention symptoms and ADHD hyperactive/ impulsive symptoms (N = 217). Note: 80% confidence intervals around the standardized parameter estimates were calculated and only CD to peer alcohol and drug use includes zero. ADHD = attention deficit=hyperactivity disorder; A = adolescent report; P = parent report; Hyper Sx = hyperactivity=impulsivity symptoms; Inatt Sx = inattention symptoms; CD = conduct disorder. +p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. χ2 (13) = 16.23, p = .24; CFI = .97, RMSEA = .03. Note. High hyperactivity = 1 SD or more above the mean for hyperactivity symptoms (β = −.13, ns). Low hyperactivity = 1 SD or more below the mean for hyperactivity symptoms (β = .39, p < .01).

FIGURE 3.

Lifetime use of alcohol and drugs and CD in youth with low versus high hyperactivity symptoms. Note: High hyperactivity = 1 SD or more above the mean for hyperactivity symptoms (β = −.13, ns). Low hyperactivity = 1 SD or more below the mean for hyperactivity symptoms (β = .39, p < .01).

DISCUSSION

This study examined the role of ADHD with and without comorbid CD, family, school, and peers in alcohol and drug use among Hispanic early adolescents. We found that poor school functioning and peer alcohol and drug use were directly associated with early alcohol and drug use. These relationships between poor school functioning and alcohol and drug use were anticipated and suggest that the association between school risk factors and early substance use is not completely explained by affiliation with substance using peers. Findings from studies using mainly non-Hispanic White samples indicate that school risk factors may be associated with early substance use through psychosocial factors, including beliefs about the deleterious effects of substance use on future career aspirations (Henry, Swaim, & Slater, 2005). However, these factors were not measured in this study. It would be important to examine whether and how these factors might explain the relationship between school risk factors and early adolescent substance use in Hispanic samples.

The finding that peer substance use was directly related to alcohol and drug use is consistent with much of the extant literature (e.g., Dishion et al., 2004), which has found that the peer context is more proximally related to early substance use, whereas other contexts (e.g., family and school) are less proximal. Possibly the role of the peer context may be of particular importance among youth with ADHD and comorbid CD because they are at greater risk of associating with deviant peers (Marshal et al., 2003) and less likely to associate with prosocial peers (Hoza et al., 2005).

We also found that adolescent report of family functioning was mediated through ADHD + CD, poor school functioning, and peer substance use. Our finding that family functioning indirectly impacted early substance use through association with substance using peers is also consistent with prior work (e.g., Drabick et al., 2006) and extends past research by examining the role of multiple contexts (peer and school) and diagnostic correlates (i.e., ADHD and CD) as possible mediators of the relationship between family functioning and substance use. Decreases in family functioning as evidenced by decreases in parental involvement, behavior management, and parental monitoring have been found to increase the influence of peers on adolescent substance use (Coombs & Paulson, 1988; Dishion et al., 2004). Indeed, findings from past research suggest that youth from families where parents monitor school work less and have fewer rules about peer activities are more likely to use substances (Coombs & Paulson, 1988). The importance of family functioning may be greater among youth with ADHD and CD because poor family functioning tends to co-occur with these disorders (Drabick et al., 2006; Rey et al., 2000), and family strengthening programs may be one way to intervene with adolescents with ADHD and comorbid CD.

The indirect relationship of family functioning with early substance use through poor school functioning is also consistent with previous research on Cuban and Latin American youth (e.g., Pilgrim et al., 2006). Parental involvement has been found to influence school functioning presumably by increasing achievement motivation and self-perception of academic competence. In turn, Cuban and Latin American youth with high levels of school achievement have been found to be at decreased risk for substance use (Bryant et al., 2003; Pilgrim et al., 2006).

We also found that the effects of ADHD + CD were mediated through poor school functioning and peer alcohol and drug use. Youth with ADHD and comorbid CD often evidence lower school achievement and attainment, as well as difficulties in peer relationships (Landau, Milich, & Diener, 1998) and our results suggests that this may also be true for Hispanic adolescents. Barkley and colleagues (Barkley et al., 2006) found that youth with ADHD and comorbid CD had fewer close friends and more trouble keeping friends. Attending to the combination of social and academic difficulties, while highlighting the importance of the school context for increasing risk for early adolescent substance use, provides a potential target for interventions to prevent substance use in adolescents with ADHD and comorbid CD.

Risk for substance use associated with ADHD + CD is a complex issue because results from past research vary by ADHD measurement (i.e., categorical and dimensional). Results from this study are consistent with Marshal and Molina (2006), who found that peer substance use mediated the relationship between ADHD and substance use for youth with elevated symptoms of either CD or oppositional defiant disorder but not for youth without these comorbid diagnoses. These findings suggest that youth with ADHD and comorbid CD are at greater risk for early substance use compared to youth with ADHD and without CD (e.g., Fergusson et al., 2007). However, the significant interaction of hyperactivity symptoms with CD suggests that youth with high levels of hyperactivity symptoms are at increased risk for alcohol and drug use compared to youth with low levels of hyperactivity symptoms irrespective of the presence of CD. Taken together, these results underscore the importance of ADHD and CD in increasing risk for alcohol and drug use among Hispanic youth.

Finally, we found a high rate of comorbidity in our sample, which is not surprising given that youth with conduct problems and ADHD are at increased risk for comorbid anxiety and depression (Biederman et al., 2004; Capaldi, 1991, 1992; Costello et al., 2003). Indeed, the odds ratio for concurrent comorbid anxiety in ADHD youth was found to be 7.7 in a recent study (Costello et al., 2003). In addition, this comorbidity seems to persist into adulthood. The high rate of comorbidity with internalizing disorders in this sample is of concern because depression and anxiety disorders in substance using youth may be associated with poorer prognosis by intensifying psychiatric symptoms, severity of substance use, impairing psychosocial functioning, and interfering with effective engagement in substance treatment (Riggs et al., 1995; Riggs & Whitmore, 1999; Young et al., 1995).

Limitations

Our results should be interpreted in light of several important limitations. First, the sample of youth with ADHD was drawn from the baseline assessment of a randomized clinical trial testing the efficacy of an HIV and substance use prevention intervention. Although all families of behavior problem adolescents in the three participating middle schools were invited to participate, prior studies have identified differences between families who agree to participate in intervention programs and those who do not (e.g., Spoth, Redmond, & Shin, 2001). For example, Spoth and colleagues found that adolescents whose families enrolled in a family-based intervention were more likely to have parents who had greater motivation to participate than were adolescents whose families did not enroll. Because we did not have informed consent prior to screening, we were unable to collect data on students who did not attend the screening appointment. Thus, we are unable to compare participants in the study to students who did not attend the screening or to the population of behavior problem students in the participating schools. Such systematic differences may have influenced the present results in unknown ways.

Second, our study used a cross-sectional design, and the role of context in early substance use was not examined over time. As a result, no causal or directional inferences can be drawn from the results. It is important, therefore, to replicate these results longitudinally.

A third potential limitation is an exclusive reliance on self-report measures for most of the variables in our model (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). Although we include data gathered from multiple reporters (parent- and youth-report) for most variables, the use of independent reports of family functioning (e.g., observational tasks) and of substance use (e.g., biological assays) may have resulted in reduced self-report bias and provided a fairer test of the study’s research questions and hypotheses. In addition, collateral reports from peers on their substance use may also reduce reporting bias in measures of peer substance use (Prinstein & Wang, 2005).

Fourth, our model accounted for 30% of the variance in alcohol and drug use. Although this is considered a “moderate to large” effect size in behavioral research (Cohen, 1988), approximately 70% of the variance remained unaccounted for in the model, suggesting that there are other variables that may also help explain adolescent alcohol and drug use. Indeed, the development of adolescent substance use is viewed as a complex phenomenon involving multiple explanatory factors across time (Randolph, 2004), and much work remains to be done in developing models that explain more variability.

Fifth, our sample was comprised of Hispanic youth with behavior problems, which may have affected our results. As is the case with most referred samples, results from these studies do not necessarily generalize to youth in the community because referred youth present with more pathology (e.g., comorbidity and higher severity of symptoms) than youth found in community samples (Angold, Costello, & Erkanli, 1999). Also, a focus on behavior problems also decreased the amount of variability on some of our variables, which in turn may decrease the amount of variability explained in our dependent measures. (i.e., family functioning, poor school functioning, peer substance alcohol and drug use, and alcohol and drug use).

Focusing on a sample of behavior problem youth also influenced the makeup of our comparison groups. Our sample included only 6 youth with no DSM–IV diagnosis, which was too small a number for meaningful analyses. As a result it is unknown how the Hispanic youth with behavior problems and in most cases at least one DSM–IV diagnosis in our sample compared to other Hispanic youth without a diagnosis or behavior problems.

Finally, our sample of Hispanic youth, which included a large proportion of Cubans and Central Americans, may not be representative of other Hispanic youth because of differences between the Hispanic population in Miami and the U.S. Hispanic population as a whole. Taken together Cubans, Cuban Americans, Dominicans, and South Americans represent 91% of the Miami Hispanic population but only 32% of the U.S. Hispanic population as a whole (Guzman, 2001). In addition, unlike any other major American city, Hispanic Americans (mostly Cuban and Cuban Americans) hold the majority of economic and political power in Miami (Stepick & Stepick, 2002). Nonetheless, the Hispanic-dominated culture of Miami may represent a preview of what other parts of the United States— particularly those with large and rapidly increasing numbers of Hispanics (e.g., Texas, California, and the Southwest)—may look like as the Hispanic population continues to expand. In addition, these results should be considered in light of reported variations in risk for substance use across Hispanic subgroups (e.g., National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2005; Wallace et al., 2002). Our findings should be replicated with samples of Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans, who together represent 75% of the U.S. Hispanic population (Marotta & Garcia, 2003).

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that multiple contexts, as well as ADHD with and without CD, may play an important role in early substance use among Hispanic adolescents. If replicated with larger samples, the findings may also have important implications for interventions targeting multiple contexts. Recent literature reviews of interventions aimed at preventing adolescent substance use suggest that intervention programs that target multiple contexts (e.g., family, school, and peers), and that are delivered to parents as well as to youth, may reduce risk for substance use in adolescence (Lopez et al., 2008). For example, comprehensive programs that combine family-based components (e.g., effective discipline, monitoring and supervision, parent–child closeness and bonding), child-centered intervention components (e.g., attitudes, beliefs, and intentions regarding substance use), school bonding strategies, and peer-based components (bonding to pro-social peers) may be most efficacious/ effective in preventing adolescent substance use.

Among youth with ADHD, the development of CD seems to signal increased risk for substance use. As such, interventions aimed at preventing or treating CD may be useful in reducing risk for later substance use. Several intervention programs have been found to be efficacious in the prevention (e.g., Fast Track; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2002) and treatment (e.g., Helping the Non-Compliant Child; McMahon & Forehand, 2003) of CD and incorporating aspects of these programs into comprehensive preventive interventions may be useful in preventing substance use in youth with ADHD.

Finally, this sample comprised a large number of youth with ADHD and comorbid internalizing disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression). Researchers have begun to suggest that the high rates of comorbidity between conduct problems and internalizing disorders may be due shared risk factors (Caron & Rutter, 1991; Wolff & Ollendick, 2006). Identifying and addressing these risk factors in interventions to reduce risk for substance use seem warranted.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the National Institute of Mental Health grant 5R01MH40859 and National Institute on Drug Abuse grants DA40859 (C. H. Brown, PI), and DA017462 (H. Pantin, PI), as well as our colleagues from the Prevention Science and Methodology Group. We also acknowledge technical assistance provided by Vanessa Madrazo.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Contributor Information

Barbara Lopez, Miller School of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, University of Miami.

Seth J. Schwartz, Miller School of Medicine, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Miami

Guillermo Prado, Miller School of Medicine, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Miami.

Shi Huang, Miller School of Medicine, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Miami.

Eugenio M. Rothe, Robert Stempel School of Public Health, Florida International University

Wei Wang, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of South Florida.

Hilda Pantin, Miller School of Medicine, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Miami.

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA. Samples of youth: Self, parent, and teacher reports. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2002;10(4):194–203. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Angold AC, Costello JE, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. Young adult follow-up of hyperactive children: Antisocial activities and drug use. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:195–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: Adaptive functioning in major life activities. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:192–202. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000189134.97436.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes HL, Olson DH. Parent–adolescent communication scale. In: Olson DH, et al., editors. Family inventories: Inventories used in a national survey of families across the family life cycle. St. Paul: Family Social Science, University of Minnesota; 1982. pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Biglan A, Ary D, Li F. Replication of a problem behavior model with American Indian, Hispanic, and Caucasian youth. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21:133–157. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman M. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce; Census Bureau projects tripling of Hispanic and Asian populations in 50 years; Non-Hispanic whites may drop to half of total population. 2004 Retrieved on September 21, 2007, from http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/population/001720.html.

- Bergman M. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce; Earnings Gap highlighted by census bureau data on educational attainment. 2007 Retrieved September 21, 2007, from http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/education/009749.html.

- Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Doyle AE, Seidman LJ, Wilens TE, Ferrero F, et al. Impact of executive functioning deficits and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on academic outcomes in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:757–766. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL, Reckase MD, Freedman-Doan CR. The role of parenting in drug use among black, Latino and white adolescence. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2006;5:39–50. doi: 10.1300/J233v05n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant AL, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Understanding the links among school misbehavior, academic achievement, and cigarette use: A national panel study of adolescents. Prevention Science. 2000;1:71–87. doi: 10.1023/a:1010038130788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant AL, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. How academic achievement, attitudes, and behaviors relate to the course of substance use during adolescence: A 6-year, multiwave national longitudinal study. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:361–397. [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Loeber R, Lahey BB. Which aspects of ADHD are associated with tobacco use in early adolescence? Journal Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2001;42:493–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: I. Familial factors and general adjustment at Grade 6. Development and Psychopathology. 1991;3:277–300. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: II. A 2-year follow-up at Grade 8. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:125–144. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron C, Rutter M. Comorbidity in child psychopathology: Concepts, issues and research strategies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1991;32:1063–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Pathways from ADHD to early drug use. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1347–1357. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199911000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, McBride C, Briones E, Kurtines W, Szapocznik J. Ecodevelopmental correlates of behavior problems in young Hispanic females. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6:126–143. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Evaluation of the first 3 years of the Fast Track prevention trial with children at high risk for adolescent conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:19–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1014274914287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook ET, Greenberg MT, Kusche CA. People in my in my life: Attachment relationships in middle childhood; Indianapolis, IN: Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Child Development; 1995. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Coombs RH, Paulson MJ. Contrasting family patterns of adolescent drug users and nonusers. Journal of Chemical Dependency Treatment. 1988;1:59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Costello JE, Mustillo M, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R. Academic and health related trajectories in adolescence: The intersection of gender and athletics. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43:317–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delva J, Wallace JM, Jr, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. The epidemiology of alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine use among Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban American, and other Latin American eighth-grade students in the United States: 1991–2002. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:696–702. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.037051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Bullock BM. Premature adolescent autonomy: Parent disengagement and deviant peer process in the amplification of problem behavior. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:515–530. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabick DAG, Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Co-occurrence of CD and depression in clinic-based sample of boys with ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:766–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feaster DJ, Goodkin K, Blaney NT, Baldewicz T, Tuttle RS, Woodward C, et al. Longitudinal psychoneuroimmunological relationships in the natural history of HIV-1 infection: The stressor-support-coping model. In: Goodkin K, Visser A, editors. Psychoneuroimmunology: Stress, mental disorders, and health. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. pp. 179–229. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Conduct and attentional problems in childhood and adolescence and later substance use, abuse and dependence: Results of a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88(1):14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher AC, Darling N, Steinberg L. Parental monitoring and peer influences on adolescent substance use. In: McCord J, editor. Coercion and punishment in long-term perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes AC, Hoza B. Maternal attributions, affect, and parenting in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and comparison families. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:346–355. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry DB. A developmental-ecological model of the relation of family functioning to patterns of delinquency. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2000;16:169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Zelli A, Huesmann LR. The relation of family functioning to violences among inner-city minority youth. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman B. The Hispanic population: Census 2000 Brief. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Swaim RC, Slater MD. Intraindividual variability of schoolbonding and adolescents’ beliefs about the effect of substance use on future aspirations. Prevention Science. 2005;6:101–112. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-3409-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Mrug S, Gerdes AC, Hinshaw SP, Bukowski WM, Gold JA, et al. What aspects of peer relationships are impaired in children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:411–423. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: National results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2006. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007. (NIH Publication No. 07-6202) [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99:1548–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practices of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG. Effects of school-level norms on student substance use. Prevention Science. 2004;3:105–124. doi: 10.1023/a:1015431300471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau S, Milich R, Diener MB. Peer relations of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Reading and Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Difficulties. 1998;14:83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez B, Schwartz SJ, Prado G, Campo AE, Pantin H. Adolescent neurological development and its implications for adolescent substance use prevention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2008;29:5–35. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas CP, Zhang H, Fischer PW, Shaffer D, Regier DA, Narrow WE, et al. The DISC Predictive Scales (DPS): Efficiently screening for diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:443–449. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marotta SA, Garcia JG. Latinos in the United States 2000. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Molina BSG. Antisocial behaviors moderate the deviant peer pathway to substance use in children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:216–226. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Molina BSG, Pelham WE. Childhood ADHD and adolescent substance use: An examination of deviant peer group affiliation as a risk factor. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:293–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Windle M. Family, religious, school and peer influences on adolescent alcohol use: A longitudinal study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:44–53. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight PE, McKnight KM, Sidani S, Figuredo AJ. Missing data: A gentle introduction. New York: Guilford; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Forehand RL. Helping the non-compliant child: Family based treatment for oppositional behavior. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, Pelham WE., Jr Childhood predictors of adolescent substance use in a longitudinal study of children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:497–507. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, Flory K, Hinshaw SP, Greiner AR, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. Delinquent behavior and emerging substance use in the MTA at 36 months: prevalence, course, and treatment effects. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:1028–1040. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180686d96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, Smith B, Pelham WE., Jr Interactive effects of ADHD and CD on early adolescent substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:348–358. [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, Greenberg MT. Children’s relationship with teachers and bonds with school an investigation of patterns and correlates in middle childhood. Journal of School Psychology. 2000;38:423–445. [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, Greenberg M. Relationships with teachers and bonds with school: Social emotional adjustment correlates for children with and without disabilities. Psychology in the Schools. 2001;38:25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. 4th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health. The NSDUH report: Substance use among Hispanic youths. 2005 Retrieved September 21, 2007, from http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k5/Hispanicyouth.html.

- Pantin H. Ecodevelopmental measures of support and conflict for Hispanic youth and families. Miami, FL: University of Miami School of Medicine; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pfiffner LJ, McBurnett K, Rathouz PJ, Judice S. Family correlates of oppositional and CDs in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:551–563. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6737-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim CC, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Mediators and moderators of parental involvement on substance use: A national study of adolescents. Prevention Science. 2006;7:75–89. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Wang SS. False consensus and adolescent peer contagion: Examining discrepancies between perceptions and actual reported levels of friends’ deviant and health risk behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:293–306. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quay HC, Peterson DR. Manual for the Revised Behavior Problem Checklist (RBPC) Coral Gables, FL 33124: University of Miami; 1987. (Available from H.C. Quay, Department of Psychology, P.O. Box 248185) [Google Scholar]

- Randolph KA. The dynamic nature of risk factors for substance use among adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2004;13:33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rey JM, Walter G, Plapp JM, Denshire E. Family environment in attention deficit hyperactivity, oppositional defiant and CDs. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;34:453–457. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Mason CA, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Effects of family functioning and identity confusion on substance use and sexual behavior in Hispanic immigrant early adolescents. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2008;8:107–124. doi: 10.1080/15283480801938440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Mason CA, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Longitudinal relationships between family functioning and identity development in Hispanic adolescents: continuity and change. Journal of Early Adolescence. doi: 10.1177/0272431608317605. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Pantin H, Prado G, Sullivan S, Szapocznik J. Family functioning, identity, and problem behavior in Hispanic immigrant early adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25:392–420. doi: 10.1177/0272431605279843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth RL, Redmond C, Shin C. Randomized trial of brief family interventions for general populations: Adolescent substance use outcomes 4 years following baseline. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:627–642. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepick A, Stepick C. Becoming American, constructing ethnicity: Immigrant youth and civic engagement. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6:246–257. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner DL. Finding our way: An introduction to path analysis. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;50:115–122. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabot CM, Rohde LA, Bukstein O, Molina BSG, Matins C, Ruaro P, et al. Is attention-deficit/hyperactivity tivity disorder associated with illicit substance use disorders in male adolescents? A community-based case-control study. Addiction. 2007;102:1122–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Coatsworth JD. An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In: Glantz M, Hartel CR, editors. Drug abuse: Origins and interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 331–366. [Google Scholar]

- Tein J-Y, Roosa MW, Michaels M. Agreement between parent and child reports on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:341–355. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Zelli A, Heusmann LR. Assessment of family relationship characteristics: A measure to explain risk for antisocial behavior and depression in youth. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:212–223. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Gil AG. Psychiatric and substance use disorders in South Florida: Racial/ethnic and gender contrasts in a young adult cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:43–50. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JC, Ollendick TH. The comorbidity of conduct problems and depression in childhood and adolescence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2006;9:201–220. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Jr, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE, Cooper SM. Tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use: Racial and ethnic differences among U.S. high school seniors, 1976–2000. Public Health Reports. 2002;117 S1:S67–S75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SE, Mikulich SK, Goodwin MB, Hardy J, Martin CL, Zoccolillo MS, Crowley TJ. Treated delinquent boys’ substance use: onset, pattern, relationship to conduct and mood disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;37:149–162. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)01069-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]