Abstract

Robust biomarkers of neurodegeneration are critical for testing of neuroprotective therapies. The clinical applicability of such biomarkers requires sufficient sensitivity to detect disease in individuals. Here we tested the sensitivity of high field (4 tesla) proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) to neurochemical alterations in the cerebellum and brainstem in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1). We measured neurochemical profiles that consisted of 10–15 metabolite concentrations in the vermis, cerebellar hemispheres and pons of patients with SCA1 (N=9) and healthy controls (N=15). Total NAA (N-acetylaspartate + N-acetylaspartylglutamate, tNAA) and glutamate were lower and glutamine, myo-inositol and total creatine (creatine + phosphocreatine, tCr) were higher in patients relative to controls, consistent with neuronal dysfunction/loss, gliotic activity and alterations in glutamate-glutamine cycling and energy metabolism. Changes in tNAA, tCr, myo-inositol and glutamate levels were discernible in individual spectra and the tNAA/myo-inositol ratio in the cerebellar hemipheres and pons differentiated the patients from controls with 100% specificity and sensitivity. In addition, tNAA, myo-inositol and glutamate levels in the cerebellar hemispheres and the tNAA and myo-inositol levels in the pons correlated with ataxia scores (Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia, SARA). Two other biomarkers measured in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of a subset of the volunteers (F2-isoprostanes as a marker of oxidative stress and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) as a marker of gliosis) were not different between patients and controls. These data demonstrate that 1H MRS biomarkers can be utilized to non-invasively assess neuronal and glial status in individual ataxia patients.

Keywords: SCA1, MRS, ataxia, cerebellum, neurochemical profile

Spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) are a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of movement disorders characterized by loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells in combination with neuronal loss in other regions, such as the dentate nucleus and pons.1, 2 Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) was the first SCA for which the genetic defect was uncovered3 and is one of nine polyglutamine disorders identified so far.4 It is caused by the expansion of an unstable CAG repeat that results in a polyglutamine expansion in ataxin-1.2

Although there are currently no treatments for SCAs5, neurodegeneration is reversible in SCA1 mouse models by suppressing the expression of the mutant ataxin-1.6, 7 Successful implementation of such treatments will be facilitated by the establishment of objective, robust biomarkers. Biochemical changes associated with neuronal dysfunction/loss can be quantified by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) and may serve as biomarkers that directly gauge neuronal and glial status. Prior studies implicated MRS as a powerful technique to detect cerebellar biochemical alterations in SCAs.8–10 However, many grouped several SCA subtypes together, resulting in a pathogenically heterogeneous sample. Following the establishment of genetic testing for SCAs, two MRS studies performed at 1.5 tesla (T) reported lower cerebellar N-acetylaspartate (NAA) and NAA/creatine in SCA1.9, 10 At higher fields, MRS enables quantification of 10–18 neurochemicals (“neurochemical profile”).11, 12 Furthermore, metabolites can be quantified with higher precision enabling detection of differences with smaller sample sizes. Therefore, we hypothesized that multiple neurochemical abnormalities that reflect the clinical status would be detectable at 4T in the cerebellum and brainstem of patients with early-to-moderate stage SCA1. We evaluated the specificity and sensitivity of these MRS biomarkers to distinguish patients from controls. We further measured two other biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of a subset of the volunteers to compare to the MRS findings. First, we quantified F2-isoprostanes as markers of oxidative stress13 which has been suggested as a pathogenic factor in polyglutamine diseases14, and also specifically in SCA1.15 Second, we measured glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), which is a gliosis marker.16, 17 Our goal was to compare F2-isoprostane levels to the putative MRS oxidative stress markers glutathione and vitamin C and GFAP levels to the putative MRS gliosis markers myo-inositol and glutamine.

Methods

Patients, control participants and study design

Fifteen healthy volunteers and 11 patients with early-to-moderate stage SCA1 (Table 1), matched for age range, participated in the study after giving written informed consent using procedures approved by the Institutional Review Board: Human Subjects Committee of University of Minnesota. Smoking and diabetes were exclusion criteria as both may cause oxidative damage which could confound our findings. Volunteers were asked to discontinue antioxidant supplements for 3 weeks prior to the study since the most common supplemental antioxidants are eliminated over this time.18, 19

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects, CSF levels of F2-isoprostanes, GFAP, glucose and lactate in 5 patients and 5 controls and spectral quality measures (Values given as counts or as mean ± SD, as appropriate).

| SCA1 (N=11) | Controls (N=15) | P-values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Female/Male) | 4/7 | 8/7 | |

| Age (years) | 55 ± 6 | 52 ± 8 | 0.23 |

| Age of onset (years) | 44 ± 11 | N / A | |

| Disease duration (years) | 11 ± 9 | N / A | |

|

# of CAG triplet repeats in the long allele of ataxin-1 gene |

44 ± 3 (range 40–50) |

N / A | |

| SARA score | 9 ± 4 (N = 11) |

0 ± 0 (N = 10) |

< 0.01 |

| F2-Isoprostanes (pg/mL) | 27 ± 12 | 32 ± 11 | 0.57 |

| GFAP (ng/mL) | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.26 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 61 ± 6 | 57 ± 8 | 0.34 |

| Lactate (mM) | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 0.02 |

| SNR*, vermis | 16 ± 3 | 17 ± 2 | 0.27 |

|

SNR, cerebellar hemispheres |

11 ± 2 | 13 ± 1 | 0.02 |

| SNR, pons | 12 ± 2 | 12 ± 3 | 0.62 |

| Linewidth, vermis (Hz) | 6 ± 1 | 6 ± 1 | 0.53 |

|

Linewidth, cerebellar hemispheres (Hz) |

8 ± 1 | 7 ± 1 | 0.09 |

| Linewidth, pons (Hz) | 7 ± 2 | 8 ± 2 | 0.46 |

| % CSF, vermis | 33 ± 10% | 12 ± 5% | < 0.01 |

|

% CSF, cerebellar hemispheres |

7 ± 6% | 2 ± 1% | 0.02 |

| % CSF, pons | 4 ± 3% | 3 ± 1% | 0.36 |

SNR: signal-to-noise ratio

All subjects underwent MR scanning; a subset of the volunteers also underwent lumbar punctures and was evaluated by a standardized ataxia rating scale (Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia, SARA)20 within one day of MR scanning. MR spectra were acquired from 3 volumes-of-interest (VOI): vermis, cerebellar hemisphere and pons. Vermis and cerebellar hemisphere data were acquired from 9 patients and pons data from 8 patients. Useful MRS data could not be collected from two patients due to restless leg syndrome in one case and claustrophobia in the other. Vermis data were acquired from 13 controls, cerebellar hemisphere data from 11 and pons data from 10. All patients and 10 healthy controls were evaluated by the SARA to seek associations between the MRS markers and clinical status. CSF was obtained 5 from 5 patients and controls by lumbar puncture via the L3-L4 intervertebral space under local anesthesia. Routine cell count, glucose, lactate (Table 1) and protein levels were normal in all CSF samples.

MR protocol

All studies were performed with a 4T magnet (Oxford Magnet Technology, Oxford, UK) with an INOVA console (Varian, Palo Alto, CA) as described before.21 Briefly, sagittal, coronal and transverse multi-slice images were obtained with a fast spin echo sequence (repetition time TR = 4.5 s, echo train length = 8, echo spacing = 15 ms, 9 slices, 2 averages). Proton spectra from the vermis (1.0 × 2.5 × 2.5 cm3), cerebellar hemisphere (1.7 × 1.7 × 1.7 cm3) and pons (1.6 × 1.6 × 1.6 cm3) were acquired with an ultra-short echo stimulated-echo acquisition mode (STEAM) sequence (echo time TE = 5 ms, TR = 4.5 s, 128 averages). Single shot spectra were averaged over 4–8 scans for frequency and phase correction and to exclude those that showed evidence for motion prior to summing. Unsuppressed water spectra were acquired at a series of TE values (TE = 5 – 5000 ms; TR = 15 s for full relaxation) to evaluate the CSF contribution to the VOI.22

Metabolite quantification

Metabolites were quantified using an automated deconvolution program (LCModel)23 as described previously.21 The model spectra for alanine (Ala), aspartate (Asp), ascorbate/vitamin C (Asc), glycerophosphocholine (GPC), phosphocholine (PC), creatine (Cr), phosphocreatine (PCr), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glucose (Glc), glutamine (Gln), glutamate (Glu), glutathione (GSH), myo-inositol (myo-Ins), lactate (Lac), N-acetylaspartate (NAA), N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG), phosphoethanolamine (PE), scyllo-inositol (scyllo-Ins) and taurine (Tau) were generated based on previously reported chemical shifts and coupling constants.24, 25 Macromolecule spectra were acquired using an inversion recovery sequence. Metabolite concentrations were obtained relative to an unsuppressed water spectrum acquired from the same VOI assuming a water content of 72% for cerebellar hemispheres (primarily white matter) and 82% for vermis and pons.26 The metabolite concentrations were corrected for the amount of CSF (obtained by fitting the integrals of the unsuppressed water spectra at different TE values with a biexponential decay22) assuming zero concentration of metabolites in CSF27, except for glucose and lactate. The tissue concentrations of glucose and lactate were obtained based on the % CSF contribution to the VOI and a CSF concentration of 3.2 mM for glucose and 1.8 mM for lactate (Table 1). Metabolites quantified with Cramér-Rao lower bounds (CRLB, estimated error of metabolite quantification) > 50% were classified as not detected. Only metabolites quantified with CRLB ≤ 50% in at least half of the spectra from a brain region were included in the final neurochemical profile. Ala and PE in the vermis, Ala, Asp, PE and scyllo-Ins in the cerebellar hemisphere and Ala, Asp, GABA, Gln and PE in the pons were excluded from final analysis based on these criteria. If the correlation between two metabolites was consistently high (correlation coefficient < −0.5) in a given region, their sum was reported.28 Thus, total creatine (tCr, Cr+PCr) and total choline (tCho, GPC+PC) were reported in all regions and total NAA (tNAA, NAA+NAAG) and Glc + Tau were reported in the cerebellar hemispheres and pons. Therefore, 15 statistically independent concentrations were evaluated in the vermis (NAA, tCr, tCho, myo-Ins, Glu with average CRLB ≤ 7%, Gln, GSH, Tau with average CRLB < 20%, Asc, Asp, GABA, Glc, Lac, NAAG, scyllo-Ins with average CRLB ≤ 35%), 11 in the cerebellar hemispheres (tNAA, tCr, tCho, myo-Ins with average CRLB < 7%, Glu with average CRLB of 11%, Asc, GABA, Gln, GSH, Lac, Glc + Tau with average CRLB < 7 35%) and 10 in the pons (tNAA, tCr, tCho, myo-Ins with average CRLB < 7%, Glu with average CRLB of 12%, Asc, GSH, Lac, scyllo-Ins, Glc + Tau with average CRLB < 35%).

Ataxia rating scale

The SARA consists of 8 quantitative exam features for gait, stance, sitting, speech disturbance and limb kinetic functions20 and yields a composite ataxia score in the range of 0 (no ataxia) − 40 (most severe ataxia).

Isoprostane and GFAP measurements in CSF

CSF was centrifuged to remove cells and the supernatant frozen in aliquots at −80°C. F2-isoprostane levels were measured with a negative ion chemical ionization GC/MS based method as described previously.29, 30 The limit of detection was 10 pg/mL. GFAP levels were assayed by a commercially available ELISA kit which is a biotin labeled antibody based sandwich enzyme immunoassay (BioVendor, LLC, Candler, NC) specific for human GFAP with a limit of detection 0.1 ng/mL. Each sample was assayed in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

MRS data from the two groups were compared using ANCOVA, adjusting for age and gender, for each neurochemical concentration in each region separately. Secondary analyses using a linear mixed model to account for the potential correlation across regions within person were not different from results shown here. Because of a few outliers and skewness for some measures, analyses were repeated using a Wilcoxon test; results were again not different from those shown here. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were used to compute sensitivity and specificity of each neurochemical in distinguishing patients from controls. Linear regression analyses were performed to evaluate the relationship between neurochemical concentrations and ataxia scores. P-values shown have not been adjusted for multiple testing. Measures of spectral quality (signal-to-noise ratio, SNR, and linewidth) and CSF data from the two groups were compared using the two-tailed, unpaired student’s t-test.

Results

Spectral quality in patients and controls

Proton MR spectra with good SNR and spectral resolution were consistently obtained from both patients and controls (Fig. 1). The only difference in spectral quality was a slightly higher spectral linewidth in the cerebellar hemispheres of patients resulting in lower SNR (Table 1). Cerebellar atrophy was apparent by a higher CSF contribution to the vermis and cerebellar hemisphere VOI in patients.

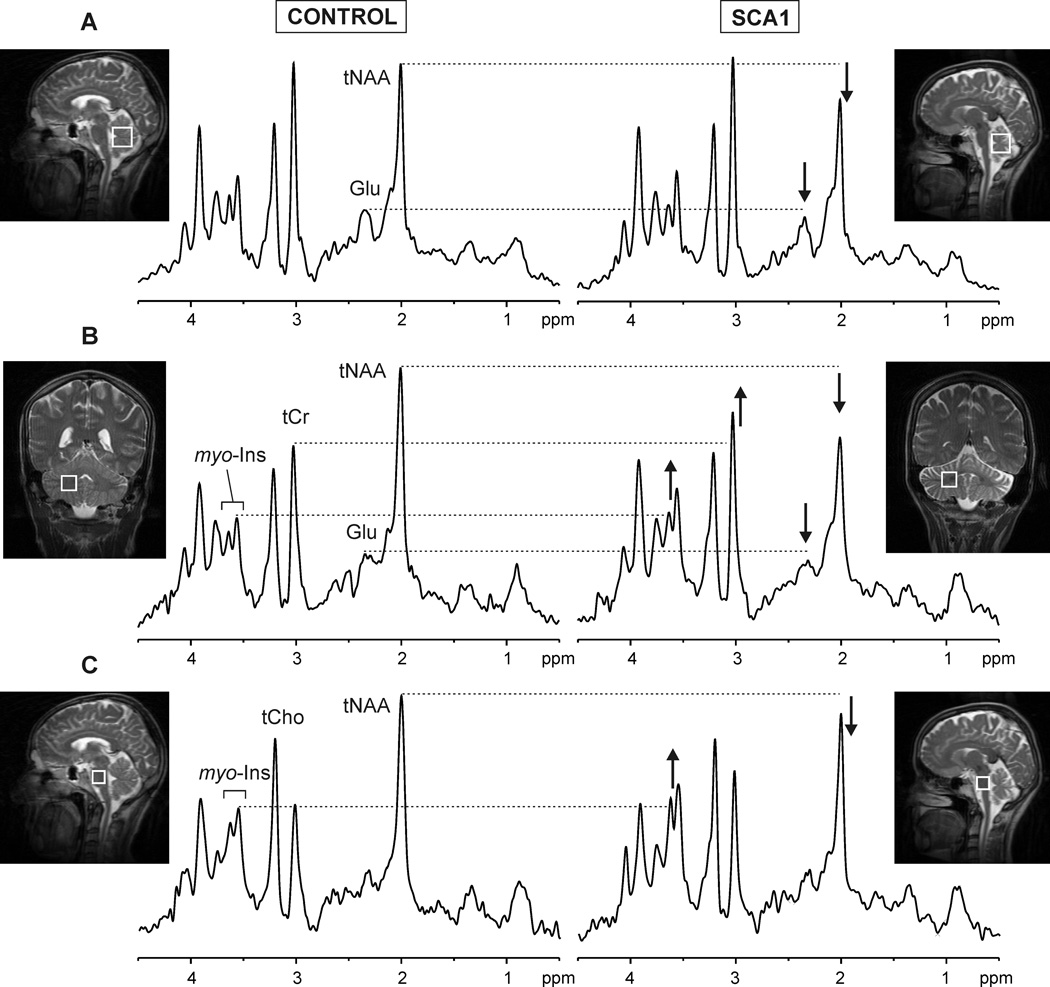

Figure 1. Localized proton MR spectra obtained from the vermis (A), cerebellar hemispheres (B) and pons (C).

Left: healthy volunteer (50 year old male); right: patient with SCA1 (55 year old female). The alterations in total NAA, glutamate, myo-inositol and total creatine visible in the spectra of the patient are shown.

The spectral patterns were characteristic of each of the three brain regions (Fig. 1, left) and the high spectral quality permitted the observation of neurochemical alterations in individual patients (Fig. 1). Specifically, decreased NAA and Glu and increased myo-Ins and tCr relative to controls were discernible in the patient spectra.

Neurochemical alterations in patients with SCA1

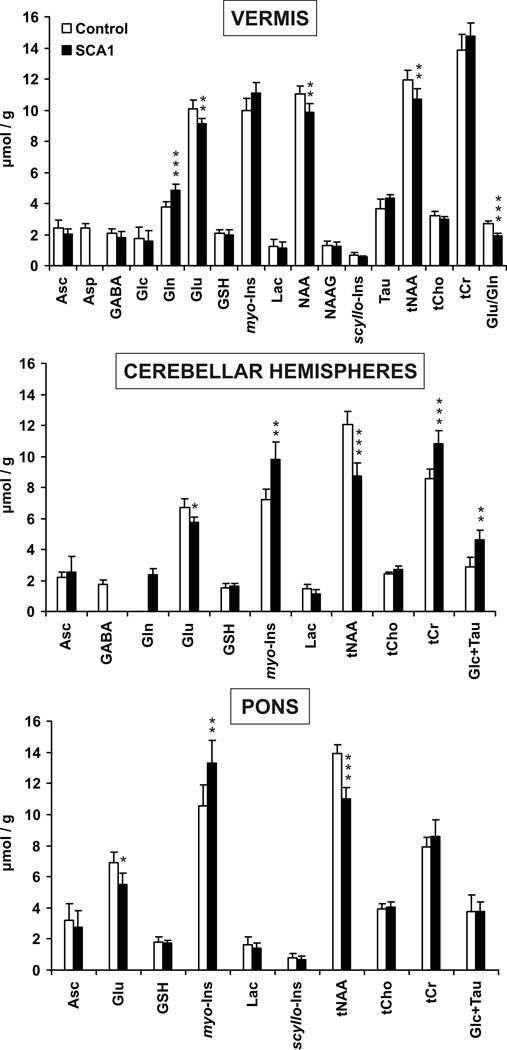

Multiple metabolites were significantly different in patients than controls (Fig. 2). In the vermis, NAA and Glu were lower and Gln higher in patients. The Glu/Gln ratio identified patients with 89% sensitivity and 100 % specificity (no false positives) based on ROC analysis. In addition, trends for lower Asp (p = 0.08) and higher myo-Ins (p = 0.1) were observed in this region and confirmed by quantifying spectra summed over all patients and controls (46% lower Asp, 16% higher myo-Ins in patients). The cerebellar hemispheres were more extensively affected than the vermis based on the significance levels of neurochemical alterations (Fig. 2). Thus, tNAA and Glu levels were lower and myo-Ins, tCr and Glc + Tau were higher here. Interestingly, GABA was not detectable (CRLB > 50%) in most patient spectra and Gln in most control spectra from the cerebellar hemispheres (Fig. 2), and analysis of summed spectra confirmed 32% lower GABA and 44% higher Gln in patients than controls. In the pons, tNAA and Glu were lower and myo-Ins higher in patients. Summed spectra further revealed lower Asp (55%) and higher Gln (125%) levels in the pons of patients than controls.

Figure 2. Neurochemical profiles of control subjects and patients with SCA1.

Only metabolites that were quantified with CRLB ≤ 50% in most subjects in a group are plotted. Error bars are 2 × S.E. (95% C.I.). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Abbreviations are in Methods.

Consistent with unchanged levels of the antioxidants GSH and Asc, there was no difference in F2-isoprostane levels in CSF (Table 1). CSF GFAP levels were also not different between patients and controls (Table 1) despite changes in the putative gliosis markers myo-Ins and Gln in the cerebellum and brainstem. Interestingly though, the patient with the highest GFAP level (2.1 ng/mL) was also the patient with the highest myo-Ins concentration in the vermis and one of the highest myo-Ins levels in the cerebellar hemispheres and pons. The average GFAP level of the remaining 4 patients was identical to that of the controls (0.9 ± 0.1 ng/mL).

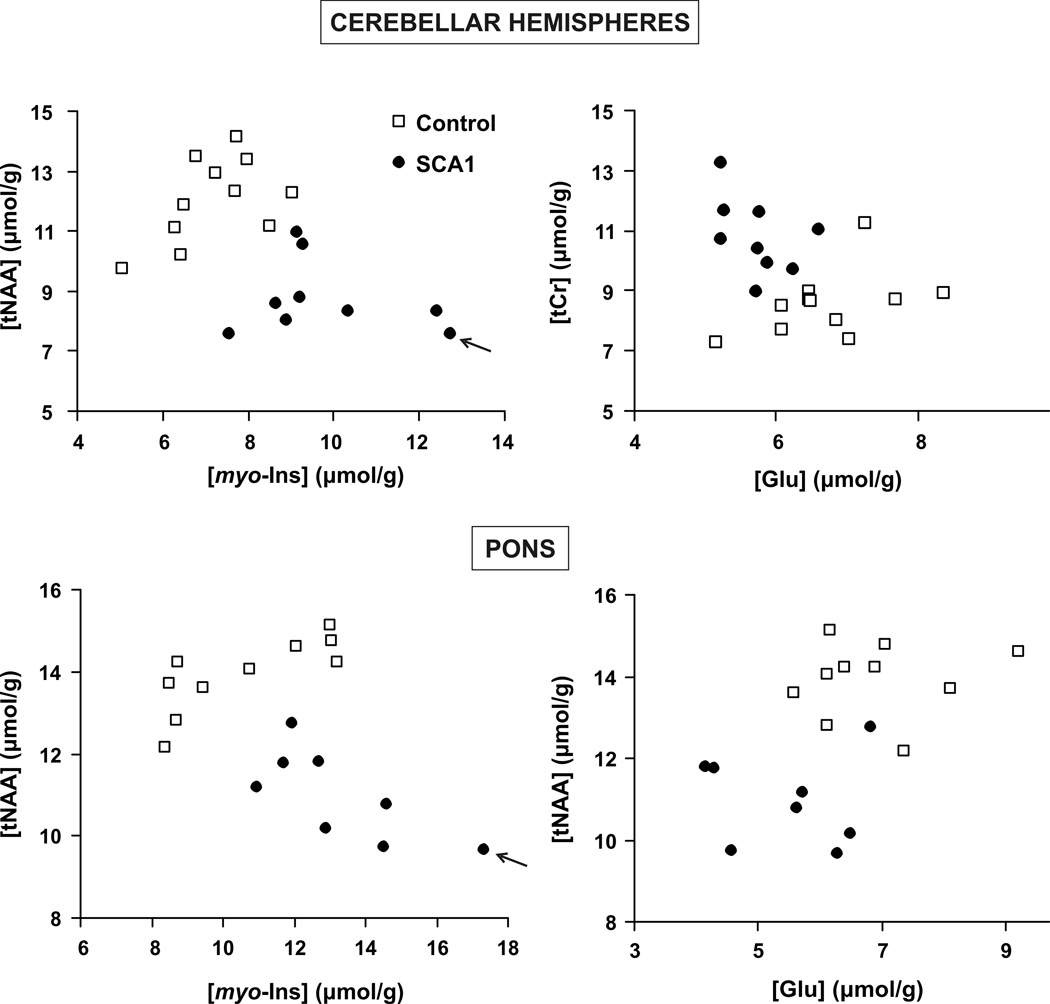

The most robust biomarkers that separated the patients from controls were tNAA, myo-Ins, Glu and tCr in the cerebellar hemispheres and tNAA, myo-Ins and Glu in the pons. Plotting their levels against each other separated the groups with no or almost no overlap (Fig. 3). In fact, the tNAA/myo-Ins ratio in both regions classified the patients with 100% specificity and sensitivity.

Figure 3. Separation of patients with SCA1 from controls based on total NAA, myo-inositol, glutamate and total creatine levels.

The patient with the highest ataxia score (14.5) had the lowest tNAA and highest myo-inositol levels (shown with arrows).

Correlations of neurochemical levels with clinical status

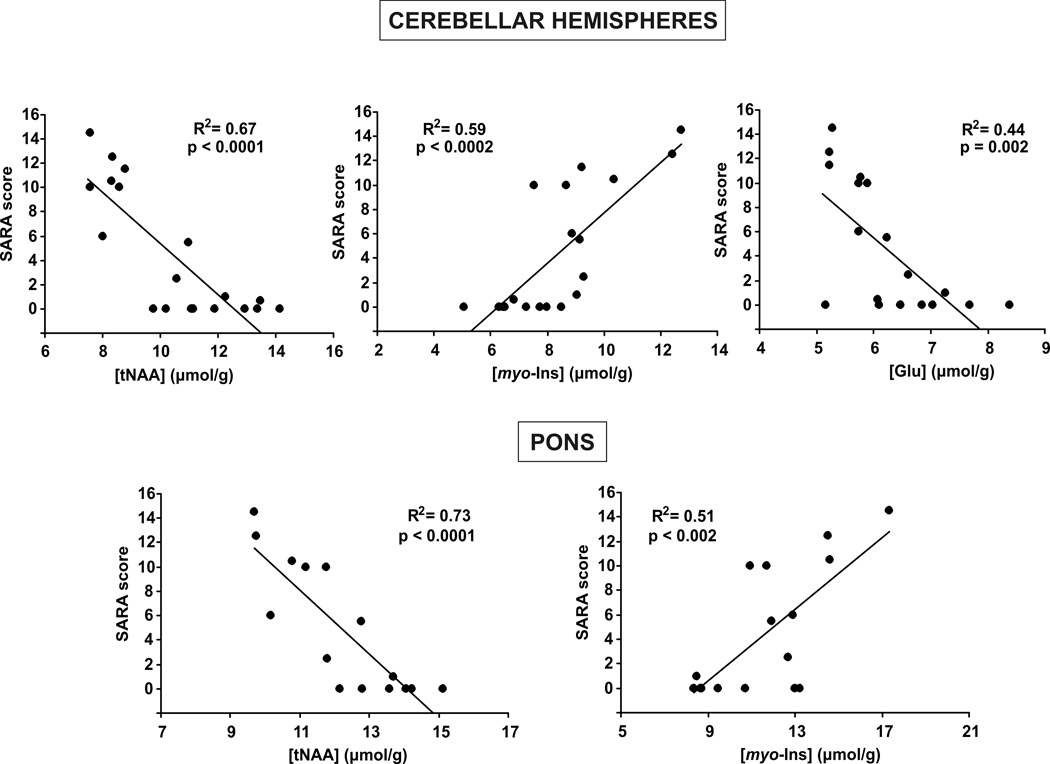

The tNAA, Glu and myo-Ins levels in the cerebellar hemispheres and tNAA and myo-Ins in the pons significantly correlated with the ataxia scores (Fig. 4). These correlations were also apparent when only the patient data (without the controls) were plotted. tNAA displayed the most robust correlations with SARA. These correlations were detectable despite the limited range of disease stage among the patients studied (the highest SARA score was 14.5 of the maximum of 40).

Figure 4. Correlation of neurochemical levels and clinical status.

Concentrations of total NAA, myo-inositol and glutamate in the cerebellar hemispheres and total NAA and myo-inositol in the pons are significantly correlated with the SARA score. Correlation coefficients and significance levels are shown.

Discussion

We report numerous neurochemical alterations in the cerebellum and brainstem of patients with SCA1 relative to healthy controls. By utilizing a 4T MR scanner we were able to detect highly statistically significant changes (Fig. 2), some of which were discernable in spectra from individuals (Fig. 1). tNAA, myo-Ins and Glu levels allowed complete separation of patients from controls (Fig. 3) and correlated with the SARA score indicating their applicability as robust biomarkers in SCAs.

We also investigated two CSF biomarkers because CSF measurements closely reflect biochemical and cellular processes active in the brain. We did not detect any indication for oxidative stress in SCA1 both by F2-isoprostane levels in CSF and the antioxidant levels measured by MRS. On the other hand, gliosis was implied by MRS, but not GFAP levels, except in one patient. Therefore, gliotic activity may need to reach a certain threshold before GFAP levels increase significantly in CSF. Taken together, these data demonstrate the advantage of direct, non-invasive measurements in the brain and suggest that cellular alterations may be too localized to cause changes in CSF.

The MRS approach has the potential to monitor multiple aspects of pathology simultaneously. The most frequently studied MRS biomarker NAA is localized exclusively to neurons and is indicative of both neuronal cell number and viability.31 NAA was decreased in all regions, in agreement with prior MRS studies of cerebellar hemispheres and pons in SCA1.9, 10 The decrease in the cerebellar hemispheres and pons was more substantial than that in the vermis, consistent with a more substantial pathological involvement and atrophy in these regions.8 In fact, the vermis has not been previously studied by MRS in SCA1 as it was thought to be relatively spared.10 In addition, glutamate was decreased and glutamine increased in the vermis of patients (Fig. 2). Glutamate is primarily localized to neurons, with the highest levels in glutamatergic neurons, while glutamine is preferentially localized in glial cells.32 Glutamine levels may increase with gliosis,21, 33 however, myo-inositol, also primarily localized to glial cells34 and typically considered a gliosis marker,21, 33, 35, 36 only showed a trend to increase in the vermis in SCA1. Therefore, the Glu and Gln changes in the vermis are likely indicative of disruptions in glutamate-glutamine cycling, which could result from loss of glutamatergic synapses in the cerebellar cortex, the principal excitatory input to Purkinje cells.

In the cerebellar hemispheres, the decreased tNAA and Glu levels were likely due to the known loss of pontocerebellar and Purkinje cell axons, as well as loss of neurons in the dentate nucleus.37 Astrocytosis is extensive in cerebellar white matter in SCA137 and was indicated by the increased myo-inositol and potentially also by increased creatine38 and glutamine levels. Summed spectra also indicated lower GABA concentrations in SCA1 which may be an indicator of loss of the axons of GABAergic Purkinje cells that contain high levels of GABA.39 The increased creatine levels may also indicate changes in cellular energy metabolism. Decreased cerebellar glucose metabolism in SCA1 was indeed demonstrated using [18F]fluorodeoxy-glucose-PET40 and increased tCr levels were also observed in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease, another CAG triplet repeat disease that involves alterations in energy metabolism.41 A previous MRS study that used VOIs very similar to ours did not find a difference in creatine levels in SCA19. In this study, metabolite levels were not corrected for CSF contribution since the researchers attempted to avoid CSF spaces by careful volume selection. However, we found that CSF contribution to the cerebellar hemisphere VOI was higher in patients than controls, even though this was not apparent on images during volume selection. Therefore metabolite concentrations may have been underestimated in patients in the previous study, at least partly explaining the discrepancy in the creatine findings.

Consistent with extensive neuronal loss and astrocytosis in the pons in SCA1,37 we observed decreased NAA, glutamate and increased myo-inositol. The levels of these metabolites in the pons and cerebellar hemispheres enabled robust separation of patients from controls (Fig. 3). In general, changes in neurochemical levels greater than twice the CRLB can be detected in individual spectra with 95% confidence.28 The mean CRLB of NAA, myo-Ins and Glu in the control spectra were 4, 5–7 and 10–11%, respectively, in the cerebellar hemispheres and pons with differences in patients of up to 37, 77 and 40% relative to controls, substantiating our ability to detect these changes in spectra from individuals (Fig. 1). These metabolites also correlated with the ataxia score (Fig. 4) indicating they are reliable markers of disease progression. This finding is consistent with a similar correlation observed between NAA levels in pons and a different ataxia score in SCA19 and extends the number of neurochemicals that can potentially serve as biomarkers in SCA1.

Other changes observed in summed spectra, e.g. decreased GABA, need to be substantiated further to be utilized as reliable biomarkers, since these analyses do not permit a statistical comparison. Also note that the specificity and sensitivity levels reported here, e.g. 100% for the tNAA/myo-Ins ratio, may be somewhat lower with a larger sample. The SCAs present the ideal test case for the specificity/sensitivity assessment due to the availability of genetic testing as the gold standard for diagnosis. Clearly, MRS would not be utilized diagnostically in SCAs; however, this analysis demonstrates the robustness of these biomarkers. While the current study was performed at a magnetic field not immediately accessible in the clinic, we expect that most of our results will be applicable to 3T, an increasingly available field strength. Two limitations of our study are a small sample size and its cross-sectional nature. To demonstrate that MRS can be used to monitor disease progression and serve as a surrogate marker in clinical trials, longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes are needed.

In conclusion, these data demonstrate the potential for high field MRS to detect neurochemical alterations in SCA1 with high sensitivity. These non-invasive biomarkers are expected to enable monitoring of disease progression and treatment efficacy on an individual patient basis because they provide a more direct assessment of neuronal and glial status than peripheral and even CSF biomarkers.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Center for MR Research for maintaining and supporting the MR system and Anthony Diebes for expert technical help with the isoprostane assay. This work was supported by a grant from the Bob Allison Ataxia Research Center (to G.Ö.) and Jay D. Schlueter Ataxia Research Fund. The 4T TEM coil was built with a grant from the Minnesota Medical Foundation (MMF 3761-9236-07 to G.Ö.). The Center for MR Research is supported by the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) biotechnology research resource grant P41RR008079 and the Neuroscience Center Core Blueprint Award P30NS057091. The General Clinical Research Center is supported by the National Center for Research Resources grant M01 RR00400.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution, D: Interpretation of results;

- Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique;

- 3. Manuscript: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and Critique.

Öz: 1, 2, 3. Hutter: 1B, 1C, 3B. Tkáč: 1C, 1D, 3B. Clark: 1D, 3B. Gross: 1C, 3B. Jiang: 1C, 3B. Eberly: 2, 3B. Bushara: 1A, 1C, 3B. Gomez: 1A, 1C, 1D, 3B.

Full Financial Disclosures of Authors for the Past Year:

Öz: Employment: University of Minnesota. Salary and research support by grants from the NIH (R01 NS035192, R21 NS060253, R21 NS056172, P41 RR008079, R01 HD057064, M01 RR00400), Bob Allison Ataxia Research Center at the University of Minnesota, Minnesota Medical Foundation and DANA Foundation.

Hutter: Employment: University of Minnesota. Salary and research support by grants from the NIH (P30NS057091, R21 NS056172, R01 CA131013) and Bob Allison Ataxia Research Center.

Tkáč Employment: University of Minnesota. Salary and research support by grants from the NIH (P41RR008079, NS35192, NCRR RR00400, R21 AG029582, P01 HD039386) and Huntington Foundation (A-1824).

Clark: Employment: University of Minnesota. Salary and research support by grants from the NIH (R01 NS 22920-13, P30-NS057091, P01NS058901, R21 NS060253).

Gross: Employment: University of Minnesota. Salary and research support by grants from the NIH (R21 NS056172, R01-HL53560-05, 5-41230-G1/R01CA116795, R01 HL093077), University of Alabama, Birmingham and University of CA, San Francisco.

Jiang: Employment: Central South University, Changsha, Hunan. Salary and research support by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30871354, 30710303061, 30400262) and the Key Project in the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No. 08JJ3048).

Eberly: Employment: University of Minnesota. Salary and research support by grants from the NIH (1R21-CA133263, 1R01-AG026392, 1R21-NS060253, 1R01-CA1205090, 1R01- NR009212) and Bob Allison Ataxia Center and contracts from the CDC (S3822) and Henry Jackson Foundation (157423).

Bushara: Employment: University of Minnesota and Minneapolis VA Medical Center. Salary and research support by grants from the Veteran Affairs Administration, NIH (R21 NS056172), Friedreich's Ataxia Research Alliance, Bob Allison Ataxia Research Center and International Essential Tremor Foundation.

Gomez: Employment: University of Chicago. Salary and research support by grants from American Parkinson’s Disease Association, NIH: J.P. Kennedy Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Center, R21 NS056172, and Friedreich's Ataxia Research Alliance (CHOP): Clinical Consortium for Research on Friedreich Ataxia, Mortality in Friedreich Ataxia.

References

- 1.Klockgether T, Dichgans J. The genetic basis of hereditary ataxia. Prog Brain Res. 1997;114:569–576. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63387-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zoghbi HY, Orr HT. Glutamine repeats and neurodegeneration. Ann Rev Neuroscience. 2000;23:217–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orr HT, Chung MY, Banfi S, et al. Expansion of an unstable trinucleotide CAG repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Nat Genet. 1993;4(3):221–226. doi: 10.1038/ng0793-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross CA. Polyglutamine pathogenesis: emergence of unifying mechanisms for Huntington's disease and related disorders. Neuron. 2002;35(5):819–822. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00872-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Prospero NA, Fischbeck KH. Therapeutics development for triplet repeat expansion diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6(10):756–765. doi: 10.1038/nrg1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xia H, Mao Q, Eliason SL, et al. RNAi suppresses polyglutamine-induced neurodegeneration in a model of spinocerebellar ataxia. Nat Med. 2004;10(8):816–820. doi: 10.1038/nm1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zu T, Duvick LA, Kaytor MD. Recovery from polyglutamine-induced neurodegeneration in conditional SCA1 transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24(40):8853–8861. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2978-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viau M, Boulanger Y. Characterization of ataxias with magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2004;10(6):335–351. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerrini L, Lolli F, Ginestroni A, et al. Brainstem neurodegeneration correlates with clinical dysfunction in SCA1 but not in SCA2. A quantitative volumetric, diffusion and proton spectroscopy MR study. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 8):1785–1795. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mascalchi M, Tosetti M, Plasmati R, et al. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in an Italian family with spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Ann Neurol. 1998;43(2):244–252. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfeuffer J, Tkáč I, Provencher SW, Gruetter R. Toward an in vivo neurochemical profile: quantification of 18 metabolites in short-echo-time 1H NMR spectra of the rat brain. J Magn Reson. 1999;141(1):104–120. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tkáč I, Öz G, Adriany G, Ugurbil K, Gruetter R. In Vivo 1H NMR Spectroscopy of the Human Brain at High Magnetic Fields: Metabolite Quantification at 4T vs. 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2009 doi: 10.1002/mrm.22086. DOI 10.1002/mrm.22086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greco A, Minghetti L, Levi G. Isoprostanes, novel markers of oxidative injury, help understanding the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurochem Res. 2000;25(9–10):1357–1364. doi: 10.1023/a:1007608615682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giuliano P, De Cristofaro T, Affaitati A, et al. DNA damage induced by polyglutamine-expanded proteins. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(18):2301–2309. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SJ, Kim TS, Hong S, Rhim H, Kim IY, Kang S. Oxidative stimuli affect polyglutamine aggregation and cell death in human mutant ataxin-1-expressing cells. Neurosci Lett. 2003;348(1):21–24. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallin A, Blennow K, Rosengren LE. Glial fibrillary acidic protein in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with dementia. Dementia. 1996;7(5):267–272. doi: 10.1159/000106891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norton WT, Aquino DA, Hozumi I, Chiu FC, Brosnan CF. Quantitative aspects of reactive gliosis: a review. Neurochem Res. 1992;17(9):877–885. doi: 10.1007/BF00993263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwedhelm E, Maas R, Troost R, Boger RH. Clinical pharmacokinetics of antioxidants and their impact on systemic oxidative stress. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42(5):437–459. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shults CW, Beal MF, Song D, Fontaine D. Pilot trial of high dosages of coenzyme Q10 in patients with Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol. 2004;188(2):491–494. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitz-Hubsch T, du Montcel ST, Baliko L, et al. Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia: development of a new clinical scale. Neurology. 2006;66(11):1717–1720. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219042.60538.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Öz G, Tkáč I, Charnas LR, et al. Assessment of adrenoleukodystrophy lesions by high field MRS in non-sedated pediatric patients. Neurology. 2005;64(3):434–441. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150906.52208.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ernst T, Kreis R, Ross BD. Absolute quantitation of water and metabolites in the human brain. I. Compartments and water. J Magn Reson. 1993;102:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Provencher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30(6):672–679. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Govindaraju V, Young K, Maudsley AA. Proton NMR chemical shifts and coupling constants for brain metabolites. NMR Biomed. 2000;13(3):129–153. doi: 10.1002/1099-1492(200005)13:3<129::aid-nbm619>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tkáč I. Refinement of simulated basis set for LCModel analysis. Proceedings of the 16th Scientific Meeting of the ISMRM; Toronto, Canada. 2008. p. 1624. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegel GJ, editor. Basic neurochemistry: molecular, cellular and medical aspects. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruse T, Reiber H, Neuhoff V. Amino acid transport across the human blood-CSF barrier. An evaluation graph for amino acid concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol Sci. 1985;70(2):129–138. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(85)90082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Provencher SW. LCModel & LCMgui User's Manual. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrow JD, Roberts LJ., 2nd Mass spectrometric quantification of F2-isoprostanes in biological fluids and tissues as measure of oxidant stress. Methods Enzymol. 1999;300:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)00106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gross M, Steffes M, Jacobs DR, Jr, et al. Plasma F2-isoprostanes and coronary artery calcification: the CARDIA Study. Clin Chem. 2005;51(1):125–131. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark JB. N-acetyl aspartate: a marker for neuronal loss or mitochondrial dysfunction. Dev Neurosci. 1998;20(4–5):271–276. doi: 10.1159/000017321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Storm-Mathisen J, Danbolt NC, Rothe F, et al. Ultrastructural immunocytochemical observations on the localization, metabolism and transport of glutamate in normal and ischemic brain tissue. Prog Brain Res. 1992;94:225–241. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61753-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pouwels PJ, Kruse B, Korenke GC, Mao X, Hanefeld FA, Frahm J. Quantitative proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of childhood adrenoleukodystrophy. Neuropediatrics. 1998;29(5):254–264. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brand A, Richter-Landsberg C, Leibfritz D. Multinuclear NMR studies on the energy metabolism of glial and neuronal cells. Dev Neurosci. 1993;15(3–5):289–298. doi: 10.1159/000111347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vrenken H, Barkhof F, Uitdehaag BM, Castelijns JA, Polman CH, Pouwels PJ. MR spectroscopic evidence for glial increase but not for neuro-axonal damage in MS normal-appearing white matter. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53(2):256–266. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kantarci K, Petersen RC, Boeve BF, et al. 1H MR spectroscopy in common dementias. Neurology. 2004;63(8):1393–1398. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000141849.21256.ac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark HB, Orr HT. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1--modeling the pathogenesis of a polyglutamine neurodegenerative disorder in transgenic mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59(4):265–270. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.4.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guerrini L, Belli G, Mazzoni L, et al. Impact of cerebrospinal fluid contamination on brain metabolites evaluation with 1H-MR spectroscopy: a single voxel study of the cerebellar vermis in patients with degenerative ataxias. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30(1):11–17. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J. Glutamate- and GABA-containing neurons in the mouse and rat brain, as demonstrated with a new immunocytochemical technique. J Comp Neurol. 1984;229(3):374–392. doi: 10.1002/cne.902290308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wüllner U, Reimold M, Abele M, et al. Dopamine transporter positron emission tomography in spinocerebellar ataxias type 1, 2, 3, and 6. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(8):1280–1285. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.8.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tkáč I, Dubinsky JM, Keene CD, Gruetter R, Low WC. Neurochemical changes in Huntington R6/2 mouse striatum detected by in vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy. J Neurochem. 2007;100(5):1397–1406. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]