Abstract

While endogenous Myc (c-myc) and Mycn (N-myc) have been reported to be separately dispensable for murine embryonic stem cell (mESC) function, myc greatly enhances induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell formation and overexpressed c-myc confers LIF-independence upon mESC. To address the role of myc genes in ESC and in pluripotency generally, we conditionally knocked out both c- and N-myc using myc doubly homozygously floxed mESC lines (cDKO). Both lines of myc cDKO mESC exhibited severely disrupted self-renewal, pluripotency, and survival along with enhanced differentiation. Chimeric embryos injected with DKO mESC most often completely failed to develop or in rare cases survived but with severe defects. The essential nature of myc for self-renewal and pluripotency is at least in part mediated through orchestrating pluripotency-related cell cycle and metabolic programs. This study demonstrates that endogenous myc genes are essential for mESC pluripotency and self-renewal as well as providing the first evidence that myc genes are required for early embryogenesis, suggesting potential mechanisms of myc contribution to iPS cell formation.

Keywords: Embryonic stem cells, Myc, iPS cells, Pluripotency, Self-renewal

1. Introduction

myc proto-oncogenes encode transcription factors belonging to the superfamily of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLHZ) proteins. The three main myc family members are involved in fundamental normal cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (Meyer and Penn, 2008). Constitutive targeted disruption of c-myc causes embryonic lethality around E10.5 with embryos exhibiting hematopoietic and vascular defects (Davis et al., 1993). c-myc has also been shown to play a pivotal role in B and T cell development (Douglas et al., 2001; Trumpp et al., 2001). Embryos, constitutively lacking N-myc, die before E11.5 and display a host of defects including disrupted neuroectodermal, heart, and lung development (Stanton et al., 1992; Charron et al., 1993; Nagy et al., 1998; Moens et al., 1992). Conditional knockout of N-myc in neural stem and progenitor cells (NSC) leads to a profound disruption of brain growth attributable in part to altered NSC cell cycling (Knoepfler et al., 2002). Although widely expressed in the murine embryo, L-myc appears to be dispensable for embryonic development (Hatton et al., 1996). Together these studies indicate that both c- and N-myc are key regulators of embryogenesis from midgestation onward, but leave open the question of potential roles for myc genes in early embryonic development. Surprisingly, separate disruption of c- and N-myc had no reported effect on mESC biology (Davis et al., 1993; Sawai et al., 1991). The lack of phenotype of the single KOs may be explained by the fact that c- and N-myc appear to be highly redundant (Malynn et al., 2000).

Recently, interest in myc function in stem cells was reignited by studies linking both c- and N-myc to the generation of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Okita et al., 2007; Sridharan et al., 2009), to the regulation of LIF signaling in mESC (Cartwright et al., 2005; Bechard and Dalton, 2009), and to tumor stem cells as well (Wang et al., 2008). iPS cells have subsequently been produced by many other groups (Yamanaka, 2009) and in the course of these studies, although iPS cell production without ectopic c-myc has been reported (Nakagawa et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2007), efficiency was dramatically reduced highlighting an important role for myc in establishing pluripotency. Subsequently, genomics studies have suggested that the reprogramming is inefficient in the absence of ectopic c-myc expression because c-Myc acts to repress fibroblast-specific gene expression, an event that is predicted to be important early in the reprogramming process (Sridharan et al., 2009). Collectively, these findings indicate there are critical, if yet to be fully defined roles for myc genes in self-renewal and pluripotency.

We hypothesized that the single KO studies of c- and N-myc in mESC failed to reveal their functions in ESC due to the remaining presence of the other main myc gene. To test this hypothesis and analyze myc function in ESC as well as in early embryogenesis, we have simultaneously disrupted both c- and N-myc using two novel myc doubly homozygously floxed (c-mycflox/flox; N-mycflox/flox) mESC lines, into which Cre recombinase was introduced. After knockout of c- and N-myc, both cDKO mESC lines exhibited profound disruption of pluripotency and selfrenewal. Our studies demonstrate that loss of c- and N-myc not only triggers growth inhibition due to cell cycle arrest and an increase in apoptosis, but it also strongly induces differentiation into ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm derivatives. Gene expression signatures indicative of more advanced differentiation into a number of lineages including neuronal, sensory organ, and hematopoietic were also evident. c- and N-myc are also essential for early embryogenesis as chimeric embryos formed with microinjected myc DKO mESC most often failed to develop and when they did form, they had very severe defects. These results indicate that myc genes are crucial for maintenance of pluripotency and self-renewal of mESC both in vitro and in vivo, with important implications for iPS cells and tumor stem cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Myc doubly floxed mES cell line generation

Twenty-one blastocysts and eighty-two morula were harvested from either seven 3-week-old or four 6-week-old myc doubly floxed superovulated female mice that had been crossed with myc doubly floxed males. The blastocysts were immediately seeded onto mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in KOSR medium, and the morula were cultured in KSOM medium overnight to attain the blastocyst stage and then seeded onto MEFs. Forty-five of the sixty-eight embryos developed ICM outgrowths that were disaggregated into ESC media and passaged to derive fifteen lines, five of which yielded metaphase spreads that had 80% or greater normal karyotype. Out of five newly generated myc doubly floxed lines, two lines (cDKO2 and cDKO3) were chosen for further analysis.

2.2. Cell culture and retroviral transduction

Cells were grown in ES complete medium consisting of high glucose DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS (HyClone), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 U/ml streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 × Glutamax, 1 × NEAA (Gibco), with 1000 U/ml LIF (ESGRO, Chemicon) on feeder layers of irradiated MEF cells (Millipore). Retroviral work was conducted as described (Takahashi et al., 2007). cDKO-2 and cDKO-3 mESC lines displayed normal morphology, expression of SSEA-1, Oct3/4, Nanog, Alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity, and normal karyotype (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2).

2.3. Genotyping and gene copy number analysis by qPCR

GFP positive mESC were sorted using the inFlux Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences). Genomic DNA was isolated from the sorted ESC using PureLink Genomic DNA purification mini kit (Invitrogen). Genotyping for c- and N-myc was conducted using multiplex PCR with single reactions that can strongly detect WT, floxed, and null alleles. Primers for c- and N-myc are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Real-time qPCR for detection of gene copy number changes was performed using SYBR Green I detection as described (Hoebeeck et al., 2007). Primers are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

2.4. Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphatebuffered saline (PBS) for 20 min. Cells then were stained using mouse anti-SSEA-1 (Chemicon), rabbit anti-GATA6 (Abcam), rabbit anti-alpha smooth muscle Actin (Abcam), mouse anti-α-fetoprotein (R and D systems), mouse anti-TUJ1 (Covance), rabbit anti-Bmp4 (Abcam), rabbit anti-neurogenin3 (Abcam), and Alex-aFluor 546-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocols. AP staining was performed using the alkaline phosphatase substrate kit III (Vector Laboratories). Cells were visualized by a Nikon ECLIPSE 80i fluorescent microscope.

2.5. Flow cytometry

For the analysis of apoptotic cells, mESC were stained for Annexin V-APC (BD Pharmingen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. For the analysis of SSEA-1 expression, cells were incubated with PE-conjugated anti-SSEA-1 antibody (R and D systems) or with PE-conjugated mouse isotype control IgM antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C. FACS analysis was performed using a CyAn ADP flow cytometer (Dakocytomation) and data was analyzed using Summit V 4.3 software. For the cell cycle analysis, mESC were pulsed with 10 μM BrdU (BD Pharmingen) for 30 min. BrdU incorporation assays were performed using the BrdU APC Flow Cytometry kit (BD Pharmingen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. FACS analysis was performed using a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

2.6. Chimeric embryo assays

GFP and GFP-Cre transduced mESC (sorted using the inFlux Cell Sorter, BD Biosciences) were microinjected into early stage embryos (8 cell, morula, or blastocysts), with the stage matched between GFP and GFP-Cre transduced mESC. Total numbers of injected embryos from 2 independent experiments were as follows: WT GFP: 29, WT GFP-CRE: 38, L2 GFP: 30, L2 GFP-CRE: 41, L3 GFP: 45, L3 GFP-CRE: 53. Microinjected embryos were transferred to pseudopregnant females and allowed to develop for 8–9 days before harvesting and microscopic analysis.

2.7. RT-PCR, qPCR, and gene expression analysis

GFP positive mESC were sorted using the inFlux Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences). Total RNA was isolated from the sorted ESC using the RNeasy Plus mini kit (Qiagen, Catalog #74134) as described by the manufacturer. RNA was reverse-transcribed by using Superscript III First strand Synthesis Supermix (Invitrogen). Primer sequences for PCR are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

qPCR assays were performed in triplicate using Invitrogen Express qPCR Supermix with Applied Biosystems Taqman assays on a Roche LightCycler 480. Expression was normalized using Eif4g2 (Nat1). Sample data was analyzed using the comparative Ct method and standard deviation calculated based on Applied Biosystems methods (Bulletin 04371095).

For gene expression analysis, isolated RNA (40 ng/μl) was submitted to the UC Davis Expression Analysis Core for gene expression analysis using the Illumina Sentrix Expression Beadchip (Mouse-6 v.3). Obtained results were analyzed with DAVID 2008 Functional Annotation Bioinformatics Microarray software.

3. Results

3.1. Loss of c- and N-myc disrupts mESC pluripotency, triggering lineage commitment

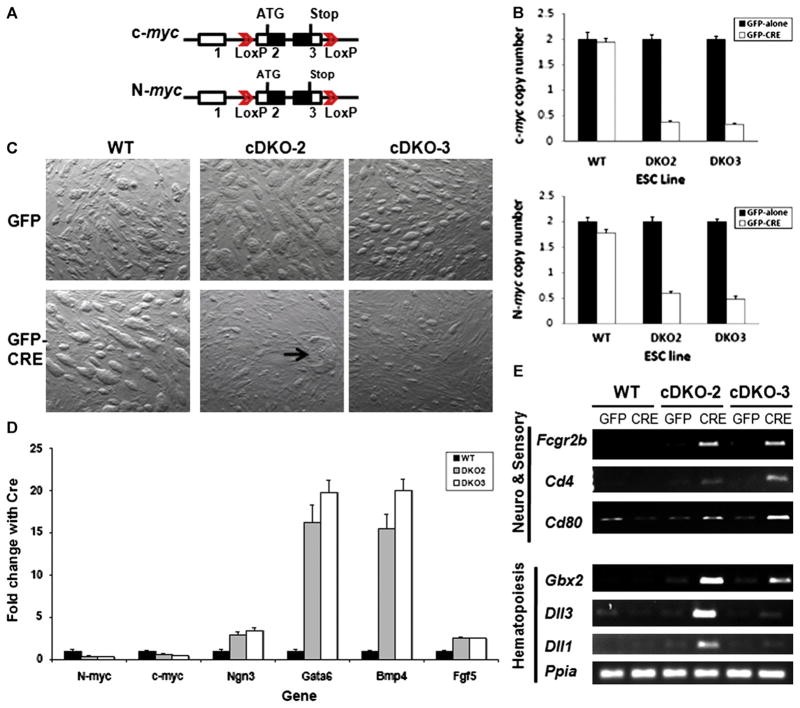

To examine the function of myc genes in mESC self-renewal and pluripotency as well as in early embryogenesis, we created two novel myc doubly homozygously floxed (c-mycflox/flox; N-mycflox/flox; Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. S1A) mESC lines, cDKO-2 and cDKO-3. Both cDKO lines were characterized as having a normal karyotype and pluripotency marker expression prior to use (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2). To produce a double myc knockout (DKO), the cDKO lines were transduced with an MSCV retrovirus containing a GFP-ires-Cre (GFP-Cre) recombinase bicistron. We have used this virus in the past for efficient myc KO in vitro in NSC (Knoepfler et al., 2002). We employed quantitative genomic qPCR to measure c- and N-myc gene copy numbers and found that they were reduced approximately 4-fold in cDKO lines transduced with GFP-Cre, but not in WT lines transduced with GFP-Cre (Fig. 1B). After 5 days of Cre expression, cDKO mESC exhibited a significant inhibition of colony growth (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. S3A and B), while Cre had no discernable effect on WT mESC. Thus, infecting cDKO-2 and cDKO-3 mESC lines with GFP-Cre virus is a very efficient method of conditional myc gene disruption.

Fig. 1.

Loss of c- and N-myc disrupts mESC growth and triggers lineage commitment. (A) Schematic of the floxed c- and N-myc loci. (B) Detection of c- and N-myc gene copy number changes by real-time qPCR. Gene copy numbers for c- and N-myc were normalized using two reference genes, β-actin and Nat1. Error bars are standard deviations. Decreases in c- and N-myc copy numbers had p values of 8.3×10−7 and 7.2×10−7, respectively, in cDKO2, and p values of 1.6×10−7 and 2.4×10−5 in cDKO3, respectively. (C) Phase contrast image of mESC lines in the presence or absence of CRE expression. Arrow denotes differentiated colony. GFP and GFP-Cre denoted cell cultures transduced with MSCV ires-GFP and MSCV Cre-ires-GFP retroviruses, respectively. (D) Real-time qRT-PCR of c-myc, N-myc, and a series of different lineage-specific marker genes in WT and DKO mESC lines. Levels of specific mRNAs measured by qRT-PCR were normalized to the levels of the loading control Nat1. Error bars are standard deviations. Changes in relative expression of N-myc, c-myc, Ngn3, Gata6, Bmp4, and Fgf5 had p values of 7×10−4, 2×10−4, 1×10−3, 8.6×10−5, 9×10−4, and 9.6×10−4, respectively, in cDKO2 and p values of 8.7×10−5, 1.4×10−5, 2.7×10−4, 3.4×10−4, 5.1×10−4, and 1.3×10−3, respectively, in cDKO3. (E) RT-PCR of hematopoietic, neural and sensory organ differentiation markers in mESC of the indicated genotype.

To test whether simultaneous depletion of c- and N-myc disrupts colony growth by impairing pluripotency, we analyzed the expression of differentiation markers in the two cDKO mESC lines by RT-PCR, qRT-PCR, and immunofluorescence analysis. cDKO-2 and cDKO-3 cells transduced with Cre exhibited 3–5 fold decreases in c- and N-myc levels (Fig. 1D). Because Myc RNA and proteins are known to have extremely short half-lives with a typical half-life of approx. 30 min, Myc protein levels in these cells should exhibit similar decreases (Hann and Eisenman, 1984). The myc-deficient cells also showed significant induction of a variety of lineage markers such as Bmp4, gata6, Fgf5, and Ngn3 relative to GFP control transduced mESC (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Figs. S4 A and B).

3.2. Loss of myc drives differentiation-associated gene expression in mESC strongly including expression of hematopoietic and neuronal/sensory organ lineage genes

Microarray gene expression experiments were performed at days 5 and 7 of Cre expression in cDKO lines to capture the dynamic changes in the mESC transcriptome associated with the loss of myc. We found that 437 genes after 5 days of CRE expression and that 688 genes after 7 days of CRE expression were up-regulated at least 1.5-fold in both cDKO mESC lines, but not in the WT cell line. Gene expression profiles of cDKO cell lines revealed a significant increase in expression of differentiation markers such as Ngn3, Fgf5, Bmp4, and gata6, which confirmed our initial RT-PCR and qRT-PCR data (Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Fig. S4A, and Fig. 1D). Importantly, ontological functional annotation analysis (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) of the genes up-regulated in both cDKO-2 and cDKO-3 lines with 5 days of Cre expression revealed upregulation of 15 genes involved in hematopoietic differentiation (p=2.2×10−4) including Vav1, Egr1, and Epas-1 (Supplementary Table S1). The loss of myc also triggered upregulation of 19 transcriptional activators (p=1.2×10−4) including Stat1, Egr1, and Elk3, which are known to drive hematopoietic differentiation (Supplementary Table S1). These data suggest that loss of myc drives mESC to differentiate toward hematopoietic lineages, further supported by analysis of the genes up-regulated in the cDKO cell lines after 7 days of Cre expression. Twelve up-regulated genes were involved in lymphocyte differentiation (p=1.9×10−3) and 26 genes were linked to the regulation of immune system processes (p=1.4×10−2), such as cd4, cd80, and Fcgr2b (Supplementary Table S1). These data also indicate that some mESC show gene expression signatures of progression toward advanced stages of hematopoietic, and more specifically, lymphocytic differentiation. However, due to continued expression of only modestly reduced levels of pluripotency markers such as Oct4, normal, and terminal hematopoietic differentiation is unlikely to fully occur in the cDKO cultures (Supplementary Fig. S4D), fitting with the general absence of other mature lineage markers such as SMA and low levels of TUJ1.

In addition to lymphocyte activation and differentiation, both lines of myc-deficient cells exhibited pronounced activation of markers specific to sensory organ development (p=6.9×10−4), including Dll1, Bmp4, Gbx2, and Fgfr1 genes, as well as genes specific to the lens (Crygc and Crygd) and the inner ear (Cdh23) (Supplementary Table S1). The array data were validated by conventional and qRT-PCR (Fig. 1D and E). Importantly, myc DKO also led to a pronounced upregulation of Wnt pathway genes (p=2×10−3), which can partially substitute for myc activity in iPS cell formation (He et al., 1998; Marson et al., 2008).

3.3. The pattern of genes downregulated with loss of myc suggests important roles in cellular metabolism, chromatin, and Lif signaling

Fewer genes were downregulated in myc-deficient cells than up-regulated: 131 genes were downregulated after 5 days of Cre expression and 255 genes were downregulated after 7 days of Cre expression. Only four genes were downregulated at both 5 and 7 days post-transduction in both cDKO lines: Klhl34, Espn, Gnmt, and, importantly, Lif, encoding the key mESC growth factor. Amongst the genes whose expression was downregulated at either days 5 or 7, but not necessarily both, there was down-regulation of genes involved in cellular chemical homeostasis (p=5.6×10−3) and genes regulating organelle biogenesis (p=4.4×10−2), indicating that myc DKO leads to down-regulation of general metabolic activity in mESC (Supplementary Table S1). The loss of myc also leads to down-regulation of several helicases including Chd1, which regulates open chromatin and pluripotency of ESC, suggesting a role for myc in remodeling of ESC chromatin architecture (Supplementary Table S1) (Gaspar-Maia et al., 2009).

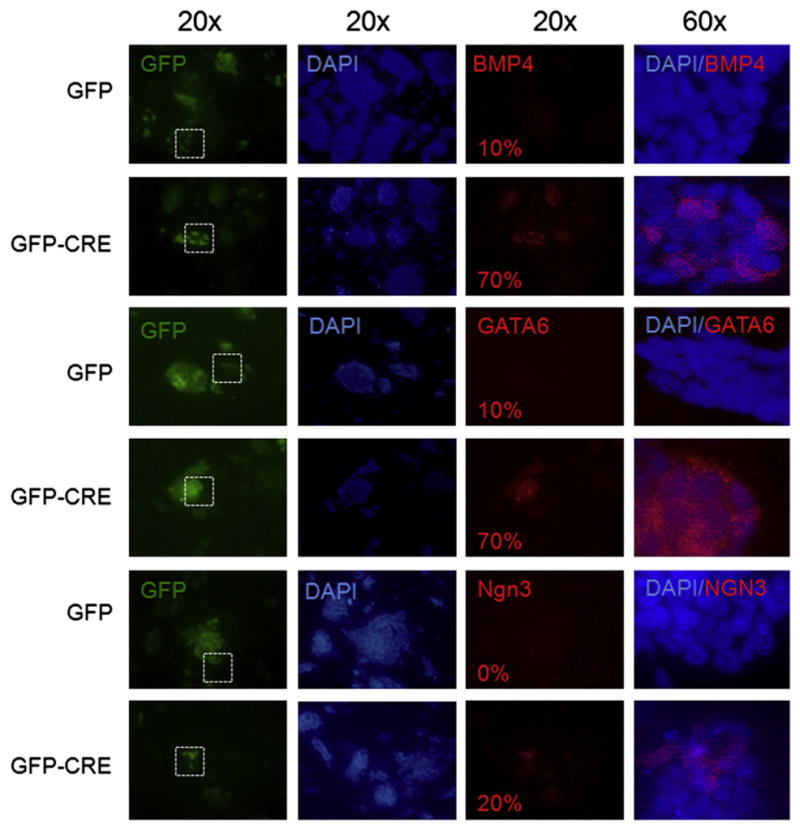

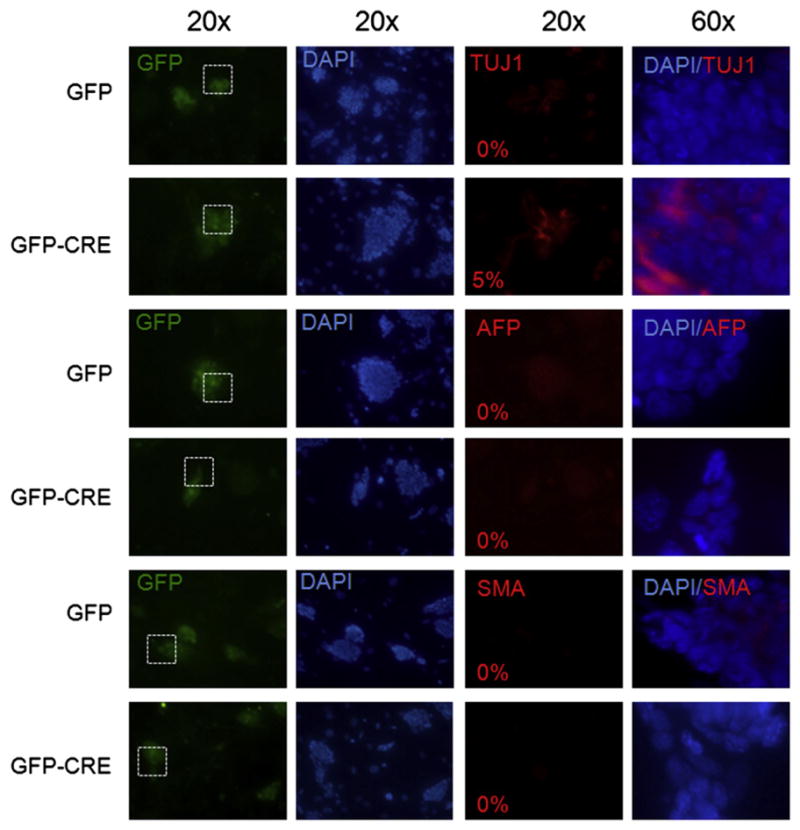

3.4. myc depletion disrupts mESC self-renewal, leading predominantly to the earliest stages of differentiation with rarer fully differentiated cells

Growth inhibition of myc cDKO mESC was accompanied by significant reduction in the expression of the early embryonic stem cell marker, SSEA-1, indicative of the loss of self-renewal (Fig. 2A and B). Similarly, alkaline phosphatase (AP) assays demonstrated a strong decrease in self-renewal in both myc-deficient mESC lines (Fig. 2C and D). Furthermore, approximately 70% of myc-deficient mESC colonies expressed GATA-6 or BMP4 differentiation markers suggesting that the majority of the colonies have entered an early stage of cell determination or differentiation (Figs. 2E and 3). To determine the percentage of differentiating cells upon myc knockdown we analyzed the expression of early (Gata6, Bmp4, and Ngn3) and late (β-TUJ, SMA, and AFP) lineage markers by immunostaining (Figs. 3 and 4). Approximately 70% of myc-deficient cells were expressing Gata6, a transcription factor expressed in primitive endoderm and cardiac mesoderm, and Bmp4, which controls mesoderm differentiation in early differentiating ES cells as well as promotes ectoderm differentiation at the expense of neural ectoderm in more differentiated ES cells (Figs. 2E and 3) (Cai et al., 2008; Peterkin et al., 2003; O’Shea 2004). Approximately 20% of myc-deficient cells expressed Ngn3, which is involved in neuroectoderm differentiation, and is expressed in endocrine progenitor cells (Fig. 3) (Gradwohl et al., 2000). In contrast, there was no detectable expression of the late differentiation markers SMA (smooth muscle cells) and AFP (visceral endoderm), but interestingly 5% of myc-deficient cells expressed TUJ1, a mature neuronal marker (Fig. 4). Although myc disruption triggered expression of differentiation markers, the mRNA levels of pluripotency regulators including Nanog, Oct4, and Rex-1, were not detectably changed (Supplementary Fig. S4C). Protein levels of Sox2 and Oct4, however, did show a modest decrease in cDKO lines after 5 days of CRE expression measured by FACS, indicative of posttranscriptional modulation of pluripotency factor expression (Supplementary Fig. S4D). Nanog levels were unchanged demonstrating that the decreases in Sox2 and Oct4, while moderate, are specific (data not shown). Passaging of myc cDKO mESC infected with GFP-Cre virus demonstrated a significant reduction of GFP+subpopulations, validating the loss of self-renewal (Supplementary Fig. S3A and B), while cDKO mESC transduced with GFP control virus as well as WT cells infected with either GFP or GFP-Cre virus exhibited robust, unaltered self-renewal. Our studies thus demonstrate that c- and N-myc are essential for maintaining mESC self-renewal.

Fig. 2.

myc depletion disrupts mESC pluripotency and self-renewal. (A) Immunofluorescent staining for SSEA-1 (red) and DAPI (blue) in the cDKO-2 mESC line. Arrow marks a representative GFP+colony, negative for SSEA-1. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of SSEA-1 expression in DKO-2 mESC line. mESC were analyzed by FACS for SSEA-1 levels with levels gated and defined as follows: negative (equal to or below levels of expression of isotype specific negative control), low (bottom third), medium (middle third), and high (top third) of SSEA-1 levels. Error bars are standard deviations. N=3. Decreases in high and medium SSEA-1 staining and increases in low and negative SSEA-1 staining had p values of 0.002, 0.005, 0.002, and 0.01, respectively, in cDKO2 and p values of 0.01, 0.002, 0.004, and 0.006 in cDKO3, respectively. (C) Fluorescent and phase contrast images of WT and DKO mESC stained for AP. Arrows denote AP staining in representative GFP-Cre positive colonies. (D) Percentage of self-renewing colonies of WT and DKO mESC lines calculated after alkaline phosphatase assays. Percentage of AP positive colonies in GFP only transduced mESC lines was defined as 100%. The error bars are SD and the data is the mean from three biological replicates (n=3). (E) Percentage of GATA6 positive cells out of GFP positive mESC (GFP alone or GFP-CRE) quantified by immunofluorescent staining for GATA6. The error bars are SD and the data is the mean from three biological replicates (n=3). P values were calculated by two-tail t-test assuming equal variances throughout this figure.

Fig. 3.

myc knockdown stimulates the expression of early differentiation markers. Immunofluorescent staining for the expression of Bmp4, GATA6, and Ngn3 in GFP control and GFP-CRE transduced DKO mESC colonies. Numbers in the bottom left corner indicate the percentage of cells expressing Bmp4, GATA6 or Ngn3 differentiation markers out of GFP positive mESC (GFP alone or GFP CRE). Images taken at 20× magnification show the expression of differentiation markers in mESC colonies, and images taken at 60× magnification show the expression of differentiation markers in individual cells within mESC colonies. White square defines region of 20× field shown in 60× panel.

Fig. 4.

myc-deficient cells do not exhibit widespread expression of late differentiation markers. Immunofluorescent staining for the expression of TUJ1, SMA, and AFP in GFP alone and GFP-CRE transduced DKO mESC colonies. Numbers in the bottom left corner indicate the percentage of cells expressing TUJ1, SMA, or AFP differentiation markers out of GFP positive mESC (GFP alone or GFP CRE). Images taken at 20× magnification show the expression of differentiation markers in mESC colonies, and images taken at 60× magnification show the expression of differentiation markers in individual cells within mESC colonies. White square defines region of 20× field shown in 60× panel.

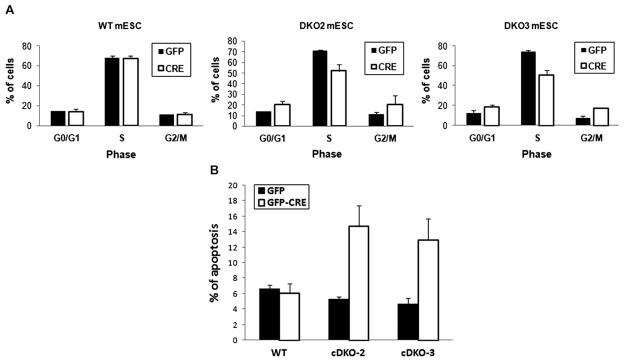

3.5. myc regulates mESC self-renewal through promoting S phase progression

Myc genes have well-characterized roles in cell cycle control and apoptosis in a variety of cell types including somatic stem cells (Wang et al., 2008; de Alboran et al., 2001). Knockdown of c-myc in glioma cancer stem cells also resulted in cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase and increased apoptosis (Wang et al., 2008). While the loss of myc strongly impairs cell cycle progression and self-renewal of somatic stem cells (Knoepfler et al., 2002; Wilson et al., 2004), roles for endogenous myc genes in mESC cell cycle have not previously been directly addressed. Here we found that c- and N-myc play an important role in the maintenance of mESC normal cell cycling. myc cDKO mESC exhibited increased expression of 14 genes involved in the regulation of progression through the cell cycle as early as 5 days of Cre expression (p=1.9×10−2; Supplementary Table S1) including cdkn1c, encoding a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor also called p57, which is essential for TGFβ-induced cell cycle arrest (Scandura et al., 2004), and gadd45g, the G2/M growth arrest gene, a known Myc target (Marhin et al., 1997). The increase in p57 (cdkn1c) and gadd45g expression in myc cDKO cell lines was confirmed by real-time qRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. S5).

We analyzed cell cycle profiles of the myc cDKO cell lines by measuring bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation coupled to the staining of DNA content with 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD). Flow cytometric analysis revealed 27–31% decreases in the fraction of cells in S phase with concomitant increase of the G0/G1 and the G2/M cell populations (Fig. 5A) in the myc cDKO mESC lines. These results indicate that myc facilitates progression through S phase and the G2-M checkpoint in mESC.

Fig. 5.

Myc is required for cell cycle progression and cell survival of mESC. (A) Cell cycle profiles of WT and cDKO mESC lines were obtained by measuring bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation coupled to the staining of DNA content with 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD). Changes in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases had p values of 0.02, 0.003, and 0.08 for cDKO2 and p values of 0.04, 0.0003, and 0.007 in cDKO3, respectively. (B) Percentage of apoptotic cells in GFP positive populations in mESC lines was measured by Annexin-V staining assay. The data are the means of three biological replicates (n=3) and error bars are standard deviations. Increases in apoptosis had p values of 0.004 and 0.006 in cDKO2 and cDKO3, respectively.

3.6. Loss of myc results in a modest increase in apoptosis in mESC

We observed an increase in the expression of genes involved in induction of apoptosis (p=3.8×10−2) in the gene expression patterns associated with the myc cDKO by ontological analysis (Supplementary Table S1). To examine potential links between myc and mESC survival, we measured apoptotic cell populations following the depletion of myc using Annexin V staining. These experiments indicated that loss of myc triggered a 3-fold increase in the levels of apoptosis after 7 days of Cre expression (Fig. 5B), while similar results were obtained at day 5 (not shown). Taken together these results demonstrate a role for myc as a survival factor for mESC, but the absolute levels of apoptosis even in DKO mESC remain relatively low, suggesting the failure of myc DKO mESC to grow is predominantly due to loss of self-renewal and pluripotency. Interestingly, c- and N-myc DKO in hematopoietic stem cells also induces apoptosis, however in a much more pronounced manner than we observed here in mESC (Laurenti et al., 2008).

3.7. c- and N-myc are essential for early embryogenesis

To investigate the role of c- and N-myc in early embryogenesis, chimeric embryo assays were conducted. GFP and GFP-Cre transduced WT and myc cDKO mESC were, in parallel, micro-injected into blastocysts and earlier embryos, followed by transplantation into pseudopregnant hosts (Supplementary Fig S6A). Embryos were harvested for analysis 8–9 days later around midgestation. Microinjection of GFP-Cre transduced WT mESC actually produced more surviving normal midgestational embryos than GFP control transduced WT mESC, and these embryos did not show any developmental abnormalities or reduction in the degree of ESC contribution to embryonic tissues, suggesting that transduction of Cre alone into mESC does not impair self-renewal and pluripotency (Supplementary Fig S6B). In contrast, microinjection of GFP-Cre transduced cDKO-2 mESC failed to produce any midgestational embryos at all (Fig. 6A) from two separate experiments totaling 41 microinjections. Microinjection of control GFP transduced cDKO-2 mESC reproducibly produced embryos an average of 40% of the time, demonstrating the intrinsic ability of cDKO-2 mESC, in the absence of Cre, to contribute normally to embryogenesis. Interestingly, chimeric embryos produced with GFP-Cre transduced cDKO-3 mESC exhibited only about an one third reduction in embryo numbers at midgestation relative to cDKO-3 transduced with GFP control virus, however none of the GFP-Cre cDKO-3 chimeric embryos were morphologically normal (Fig. 6B). Chimeric embryos produced with GFP-Cre transduced cDKO-3 mESC exhibited strongly impaired development overall and an apparent reduced contribution of GFP+mESC to embryonic tissues (Supplementary Fig. S6C).

Fig. 6.

Myc is essential for early embryogenesis. (A) Mean percentage of midgestational chimeric embryos recovered after 8–9 days postinjection in two independent microinjection experiments. The graph represents the percentage of chimeric embryos which were recovered compared to the total number of injected embryos for each cell type (defined as 100%). (B) Representative phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy images of chimeric embryos produced with cDKO-3 mESC transduced with GFP or GFP-Cre virus.

4. Discussion

Recent studies suggest that myc genes are critical for the acquisition (iPS cells) and maintenance (mESC and other stem cells) of stem cell properties, but their potential endogenous functions in self-renewal and pluripotency have not been clearly defined. The possible role of myc genes in early embryogenesis has also been a longstanding open question. Here, we find that endogenous myc genes maintain ESC self-renewal and pluripotency, and are essential for early embryogenesis.

We observed pronounced upregulation of a variety of differentiation markers in the myc DKO mESC at a point where we did not observe significant loss in mRNA levels of transcriptional pluripotency markers such as Oct4 and Nanog. The majority of myc-deficient cells expressed markers of early endoderm and mesoderm differentiation (GATA6 and Bmp4). About 20% of the population of myc-depleted cells expressed neuroectodermal marker Ngn3. However, there was no detectable expression of the more advanced differentiation markers such as AFP and SMA, and only about 5% of cells expressed TUJ1, a marker of more advanced neuronal differentiation. Since GATA6 precedes AFP expression in some endodermal cell types (Morrisey et al., 1998), and Bmp4 is expressed in early differentiating cells, compared to SMA, which is expressed in more differentiated smooth muscle cells, myc-depleted ES cultures thus mostly contain immature endo- and mesodermal precursors rather than fully differentiated cell types. The small population of more fully differentiated cells of neuronal lineage is interesting and suggests that in the absence of Myc, neuronal lineage progression may be unblocked more fully than other types of differentiation.

Myc-deficient mESC thus do not necessarily undergo terminal stages of differentiation to give rise to the fully differentiated progeny, but rather differentiate largely into early progenitor-like cells. Down-regulation of the main pluripotency markers is gradual upon differentiation, and it is likely that in the initial steps of differentiation, pluripotency factors are co-expressed with differentiation markers. Indeed, single-cell transcript analysis of hESC has demonstrated the persistence of pluripotency transcripts in differentiating cells, where multiple markers of differentiation and pluripotency are co-expressed at the single-cell level (Gibson et al., 2009). Together these data suggest that a predominant function for Myc in mESC pluripotency is potent suppression of early stages of differentiation. This notion is consistent with the finding that c-myc does not greatly contribute to the activation of pluripotency regulators in reprogrammed cells (Sridharan et al., 2009). However, we did observe modestly decreased protein levels of Sox2 and Oct4 upon myc disruption, which could be functionally important. This observation also suggests that myc can regulate ESC pluripotency not only through direct regulation of gene expression, but also through posttranscriptional events.

Additional evidence for a role of Myc in the repression of differentiation comes from observations that myc expression is normally downregulated upon induced differentiation of ESC (Sumi et al., 2007), and that overexpression of myc inhibits differentiation of a variety of cell types including hematopoietic and neuronal cells (Amanullah et al., 2000; Su et al., 2006). In addition, recent studies of the reprogramming factors involved in the induction of pluripotency have demonstrated that Myc proteins promote the induction of ESC gene expression programming in part by silencing of the somatic cell expression program (Sridharan et al., 2009). The comparison of gene expression programs operative in ESC and adult tissue stem cells has revealed two predominant gene modules that distinguish ESC and adult tissue stem cells (Wong et al., 2008). The adult tissue stem program has been reported to be downregulated by Myc (Wong et al., 2008). Interestingly, in our study, 55 genes that were up-regulated in both cDKO cell lines belong to the adult tissue stem module. The loss of myc, thus, might lead to ESC differentiation towards adult tissue stem cells, reflecting a loss of pluripotency.

In addition to potential direct suppression of expression of differentiation-associated genes, perhaps via Miz-1 (Wu et al., 2003), Myc activates expression of many genes in mESC. While some activated target genes may in turn suppress differentiation, others likely act to directly maintain self-renewal, including cell cycle and chromatin regulatory genes. The loss of proliferation in the form of cell cycle disruption likely also plays some role in inducing spontaneous differentiation. Importantly, previous work has suggested a key effector role for c-Myc in LIF/STAT3 signaling in mESC since overexpressed c-Myc confers LIF-independence (Cartwright et al., 2005). Our finding that Myc is required for maintaining normal endogenous LIF expression in mESC fits with these previous studies but also suggests a complex positive feedback loop exists between Myc and LIF. Besides LIF, the other genes downregulated by loss of Myc included those involved in multiple aspects of cellular metabolism suggesting a key role for Myc in maintaining a highly active metabolic state that may be essential for mESC self-renewal, which we found to be strictly Myc-dependent. In addition to regulating expression of specific genes, Myc may have a more widespread role in regulating ESC chromatin suggested by studies in somatic stem and tumor cells (Martinato et al., 2008; Cotterman et al., 2008; Knoepfler et al., 2006; Guccione et al., 2006). By modulating the balance of global euchromatin and heterochromatin in ESC, Myc might, therefore, make the epigenome competent for the action of pluripotency factors, which could in turn activate pluripotency and self-renewal programs as well as block differentiation.

In our study we observed a significant ES cell growth inhibition, which, in addition to elevated levels of spontaneous differentiation, could also be attributed to Myc’s ability to control cell cycle progression, cell survival, and general metabolism. Overexpression of Myc or its depletion leads to increased levels of apoptosis, suggesting that tight control of myc expression is obligatory for cell survival (Wang et al., 2008; Sumi et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008). Consistent with this notion, our study has shown that loss of myc leads to a significant decrease in the population of cells in S phase with concomitant increase of the G0/G1 and the G2/M cell populations as well as to elevated levels of apoptosis with concomitant increase in expression of cell cycle inhibitors including gadd45 and p57, as well as genes involved in apoptosis in cDKO mES cells. Interestingly, although there is a considerable decrease in the population of cells in S phase, and myc depletion leads to a significant disruption of ES colony growth, approximately 50% of DKO cells are still in S phase. One of the possible explanations is that Myc depletion triggers a differentiation program in a subset of ES cells each time they are out of S phase, however it is unlikely that DKO cells fully undergo terminal differentiation, which is associated with the entry into G0 phase of the cell cycle. myc-deficient ES cells might give rise to a variety of early progenitor-like partially differentiated cells, which grow more slowly and do not readily form colonies, but are likely still cycling, although their cell cycles are significantly slower than that of undifferentiated ESC with slower transit through all phases of the cell cycle. Cell cycle heterogeneity of partially differentiated cells thus might reconcile observed numbers of cells in S phase and significant colony growth disruption or delay. In addition to the cell cycle, the mechanisms by which myc maintains ESC self-renewal and pluripotency also likely include regulation of microRNAs (miRNA), the noncoding RNAs, which are known to have diverse roles including the regulation of cellular differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis (Ambros, 2004). In ESC, miRNAs control cell cycle progression, differentiation, and lineage determination including hematopoietic and neural differentiation (Chen et al., 2004; Krichevsky et al., 2006; Ivey et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008; Wang and Blelloch, 2009). Indeed, Dicer-null ESC that lack most mature miRNAs cannot differentiate into most lineages (Murchison et al., 2005). Recent data suggest that Myc regulates miRNA expression in a widespread fashion (Chang et al., 2008) and that Myc influences mESC biology at least in part through regulation of miRNA (Lin et al., 2009).

The role of myc genes in early murine embryogenesis has been an open question for more than two decades. While c- and N-myc constitutive knockouts are lethal around midgestation, it has been unclear what role, if any, these genes played in early development. For the first time, our data clearly demonstrate that the early embryo is strongly myc-dependent. We have observed some differences between the chimeric embryos produced by the injections of cDKO-2 (unviable embryos) and cDKO-3 (developmentally abnormal embryos) cell lines, which could be explained by the differences in chimeric contributions between these cell lines. We hypothesize that cDKO-2 injected chimeric embryos have a more severe phenotype (inviable embryos) due to a higher degree of incorporation of this cell line into chimerae, compared to the cDKO-3 cell line in which chimeric contribution is high enough to cause developmental abnormalities, but not high enough to lead to an early embryonic lethality. High-contribution chimeras produced with mutant ES cells tend to display similar defects as homozygous mutant embryos (Douglas et al., 2001; Chamberlain et al., 2008). Chimeric embryos that were almost fully composed of c-Myc−/− ES cells exhibited developmental abnormalities by E10–E11, as reported for c-Myc−/− embryos, whereas chimeras with fewer incorporated c-Myc−/− ES cells developed normally (Douglas et al., 2001). Another possibility is that the cDKO-2 cell line had a more complete loss of myc expression prior to microinjection or more persistent Cre activity after injection, compared to cDKO-3 cell line. Importantly, the differences between cDKO-2 and cDKO-3 ES cell line survival are much less prominent in cell culture, compared to the chimeric embryo assays. This could be explained by the fact that in the embryo (in vivo), there are likely more strict requirements for Myc function in highly pluripotent stem cells, whereas in vitro, in the presence of growth factors and feeder layers, cell lines can more readily survive and perhaps proliferate modestly even with lowered Myc. In addition to embryogenesis, our results also have implications for the mechanisms by which Myc causes cancer, supporting the notion that Myc “locks in” an aberrant pluripotent state rendering tumors resistant to differentiation. This notion is also supported by the recent finding that N-Myc regulates expression of pluripotency genes in neuroblastoma (Cotterman and Knoepfler, 2009).

Our data also suggest that c- and N-myc can partially compensate for each other’s loss or are functionally redundant in ESC and the early embryo. The midgestational lethality of either single constitutive myc knockout reflects the incomplete nature of this compensation or redundancy. Intriguingly, through a placental rescue approach, the function of c-myc during development was recently defined to be predominantly to drive hematopoiesis (Dubois et al., 2008). This finding supports a model in which N-myc plays the more central role in self-renewal and pluripotency of the early embryo itself.

5. Conclusion

Taken together, our findings indicate that self-renewal and pluripotency of mESC as well as pluripotent cells of the early embryo are critically dependent upon myc expression. These findings have important implications for ES and iPS cell biology and regulation of early embryogenesis, but also for tumor stem cells and tumorigenesis. Additional insight into Myc function in highly pluripotent cells and its relevance to cancer await further study, but we propose a model in which Myc directs ESC biology and iPS cell formation through regulation of protein coding and miRNA gene expression to orchestrate general metabolism, pluripotency-related cell cycle machinery, and self-renewal. Myc may also promote a generally euchromatic state important for pluripotency. During tumorigenesis these functions are “locked in” promoting the transformation of normal stem cells into tumor stem cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the UCD Gene Expression Core and Xin Yu Rairdan of the UCD Murine Targeted Genomics Laboratory for their excellent technical help as well as Laura Reinholdt, Anne Czechanski and Jocelyn Sharp for their excellent work in producing the cDKO mESC lines. This work was supported by the following grants to PK (CIRMNew Faculty Award RN2-00922-1, NIH Howard Temin Award K01 CA114400, and the Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Award from the March of Dimes) and NIH RO1 HD37102 to BBK.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.diff.2010.05.001.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit:

References

- Amanullah A, Liebermann DA, Hoffman B. p53-independent apoptosis associated with c-Myc-mediated block in myeloid cell differentiation. Oncogene. 2000;19:2967–2977. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechard M, Dalton S. Subcellular localization of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta controls embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2092–2104. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01405-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai KQ, Capo-Chichi CD, Rula ME, Yang DH, Xu XX. Dynamic GATA6 expression in primitive endoderm formation and maturation in early mouse embryogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2820–2829. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright P, McLean C, Sheppard A, Rivett D, Jones K, Dalton S. LIF/STAT3 controls ES cell self-renewal and pluripotency by a Myc-dependent mechanism. Development. 2005;132:885–896. doi: 10.1242/dev.01670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SJ, Yee D, Magnuson T. Polycomb repressive complex 2 is dispensable for maintenance of embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1496–1505. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TC, Yu D, Lee YS, Wentzel EA, Arking DE, West KM, Dang CV, Thomas-Tikhonenko A, Mendell JT. Widespread microRNA repression by Myc contributes to tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:43–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charron J, Malynn BA, Fisher P, Stewart V, Jeannotte L, Goff SP, Robertson EJ, Alt FW. Embryonic lethality in mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of the N-myc gene. Genes Dev. 1993;6:2248–2257. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science. 2004;303:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotterman R, Knoepfler PS. N-Myc regulates expression of pluripotency genes in neuroblastoma including lif, klf2, klf4, and lin28b. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotterman R, Jin VX, Krig SR, Lemen JM, Wey A, Farnham PJ, Knoepfler PS. N-Myc regulates a widespread euchromatic program in the human genome partially independent of its role as a classical transcription factor. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9654–9662. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AC, Wims M, Spotts GD, Hann SR, Bradley A. A null c-myc mutation causes lethality before 10.5 days of gestation in homozygotes and reduced fertility in heterozygous female mice. Genes Dev. 1993;7:671–682. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Alboran IM, O’Hagan RC, Gartner F, Malynn B, Davidson L, Rickert R, Rajewsky K, DePinho RA, Alt FW. Analysis of C-MYC function in normal cells via conditional gene-targeted mutation. Immunity. 2001;14:45–55. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas NC, Jacobs H, Bothwell AL, Hayday AC. Defining the specific physiological requirements for c-Myc in T cell development. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:307–315. doi: 10.1038/86308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois NC, Adolphe C, Ehninger A, Wang RA, Robertson EJ, Trumpp A. Placental rescue reveals a sole requirement for c-Myc in embryonic erythroblast survival and hematopoietic stem cell function. Development. 2008;135:2455–2465. doi: 10.1242/dev.022707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar-Maia A, Alajem A, Polesso F, Sridharan R, Mason MJ, Heidersbach A, Ramalho-Santos J, McManus MT, Plath K, Meshorer E, Ramalho-Santos M. Chd1 regulates open chromatin and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2009;460:863–868. doi: 10.1038/nature08212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JD, Jakuba CM, Boucher N, Holbrook KA, Carter MG, Nelson CE. Single-cell transcript analysis of human embryonic stem cells. Integr Biol (Cambridge) 2009;1:540–551. doi: 10.1039/b908276j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradwohl G, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Guillemot F. Neurogenin3 is required for the development of the four endocrine cell lineages of the pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1607–1611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guccione E, Martinato F, Finocchiaro G, Luzi L, Tizzoni L, Dall’ Olio V, Zardo G, Nervi C, Bernard L, Amati B. Myc-binding-site recognition in the human genome is determined by chromatin context. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:764–770. doi: 10.1038/ncb1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann SR, Eisenman RN. Proteins encoded by the human c-myc oncogene: differential expression in neoplastic cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:2486–2497. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.11.2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton KS, Mahon K, Chin L, Chiu FC, Lee HW, Peng D, Morgenbesser SD, Horner J, DePinho RA. Expression and activity of L-myc in normal mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1794–1804. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He TC, Sparks AB, Rago C, Hermeking H, Zawel L, Da Costa LT, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science. 1998;281:1509–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoebeeck J, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. Real-time quantitative PCR as an alternative to Southern blot or fluorescence in situ hybridization for detection of gene copy number changes. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;353:205–226. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-229-7:205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey KN, Muth A, Arnold J, King FW, Yeh RF, Fish JE, Hsiao EC, Schwartz RJ, Conklin BR, Bernstein HS, Srivastava D. MicroRNA regulation of cell lineages in mouse and human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoepfler PS, Cheng PF, Eisenman RN. N-myc is essential during neurogenesis for the rapid expansion of progenitor cell populations and the inhibition of neuronal differentiation. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2699–2712. doi: 10.1101/gad.1021202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoepfler PS, Zhang XY, Cheng PF, Gafken PR, McMahon SB, Eisenman RN. Myc influences global chromatin structure. Embo J. 2006;25:2723–2734. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichevsky AM, Sonntag KC, Isacson O, Kosik KS. Specific microRNAs modulate embryonic stem cell-derived neurogenesis. Stem Cells. 2006;24:857–864. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenti E, Varnum-Finney B, Wilson A, Ferrero I, Blanco-Bose WE, Ehninger A, Knoepfler PS, Cheng PF, MacDonald HR, Eisenman RN, Bernstein ID, Trumpp A. Hematopoietic stem cell function and survival depend on c-Myc and N-Myc activity. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:611–624. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, Jackson AL, Guo J, Linsley PS, Eisenman RN. Myc-regulated microRNAs attenuate embryonic stem cell differentiation. EMBO J. 2009;28:3157–3170. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malynn BA, de Alboran IM, O’Hagan RC, Bronson R, Davidson L, DePinho RA, Alt FW. N-myc can functionally replace c-myc in murine development, cellular growth, and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1390–1399. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhin WW, Chen J, Facchini LM, Fornace AJ, Penn LZ. Myc represses the growth arrest gene gadd45. Oncogene. 1997;14:2825–2834. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marson A, Foreman R, Chevalier B, Bilodeau S, Kahn M, Young RA, Jaenisch R. Wnt signaling promotes reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:132–135. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinato F, Cesaroni M, Amati B, Guccione E. Analysis of Myc-induced histone modifications on target chromatin. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer N, Penn LZ. Reflecting on 25 years with MYC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:976–990. doi: 10.1038/nrc2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moens CB, Auerbach AB, Conlon RA, Joyner AL, Rossant J. A targeted mutation reveals a role for N-myc in branching morphogenesis in the embryonic mouse lung. Genes Dev. 1992;6:691–704. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrisey EE, Tang Z, Sigrist K, Lu MM, Jiang F, Ip HS, Parmacek MS. GATA6 regulates HNF4 and is required for differentiation of visceral endoderm in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3579–3590. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchison EP, Partridge JF, Tam OH, Cheloufi S, Hannon GJ. Characterization of dicer-deficient murine embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12135–12140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505479102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy A, Moens C, Ivanyi E, Pawling J, Gertsenstein M, Hadjantonakis AK, Pirity M, Rossant J. Dissecting the role of N-myc in development using a single targeting vector to generate a series of alleles. Curr Biol. 1998;8:661–664. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Okita K, Mochiduki Y, Takizawa N, Yamanaka S. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea KS. Self-renewal vs. differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:1755–1765. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.028100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007 doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterkin T, Gibson A, Patient R. GATA-6 maintains BMP-4 and Nkx2 expression during cardiomyocyte precursor maturation. EMBO J. 2003;22:4260–4273. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawai S, Shimono A, Hanaoka K, Kondoh H. Embryonic lethality resulting from disruption of both N-myc alleles in mouse zygotes. New Biol. 1991;3:861–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scandura JM, Boccuni P, Massague J, Nimer SD. Transforming growth factor beta-induced cell cycle arrest of human hematopoietic cells requires p57KIP2 up-regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15231–15236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406771101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan R, Tchieu J, Mason MJ, Yachechko R, Kuoy E, Horvath S, Zhou Q, Plath K. Role of the murine reprogramming factors in the induction of pluripotency. Cell. 2009;136:364–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton BR, Perkins AS, Tessarollo L, Sassoon DA, Parada LF. Loss of N-myc function results in embryonic lethality and failure of the epithelial component of the embryo to develop. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2235–2247. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X, Gopalakrishnan V, Stearns D, Aldape K, Lang FF, Fuller G, Snyder E, Eberhart CG, Majumder S. Abnormal expression of REST/NRSF and Myc in neural stem/progenitor cells causes cerebellar tumors by blocking neuronal differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1666–1678. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.5.1666-1678.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi T, Tsuneyoshi N, Nakatsuji N, Suemori H. Apoptosis and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells induced by sustained activation of c-Myc. Oncogene. 2007;26:5564–5576. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Okita K, Nakagawa M, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from fibroblast cultures. Nat Protocols. 2007;2:3081–3089. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trumpp A, Refaeli Y, Oskarsson T, Gasser S, Murphy M, Martin GR, Bishop JM. c-Myc regulates mammalian body size by controlling cell number but not cell size. Nature. 2001;414:768–773. doi: 10.1038/414768a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Mannava S, Grachtchouk V, Zhuang D, Soengas MS, Gudkov AV, Prochownik EV, Nikiforov MA. c-Myc depletion inhibits proliferation of human tumor cells at various stages of the cell cycle. Oncogene. 2008;27:1905–1915. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang H, Li Z, Wu Q, Lathia JD, McLendon RE, Hjelmeland AB, Rich JN. c-Myc is required for maintenance of glioma cancer stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Baskerville S, Shenoy A, Babiarz JE, Baehner L, Blelloch R. Embryonic stem cell-specific microRNAs regulate the G1-S transition and promote rapid proliferation. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1478–1483. doi: 10.1038/ng.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Blelloch R. Cell cycle regulation by MicroRNAs in embryonic stem cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4093–4096. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A, Murphy MJ, Oskarsson T, Kaloulis K, Bettess MD, Oser GM, Pasche AC, Knabenhans C, Macdonald HR, Trumpp A. c-Myc controls the balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2747–2763. doi: 10.1101/gad.313104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DJ, Liu H, Ridky TW, Cassarino D, Segal E, Chang HY. Module map of stem cell genes guides creation of epithelial cancer stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:333–344. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Cetinkaya C, Munoz-Alonso MJ, von der Lehr N, Bahram F, Beuger V, Eilers M, Leon J, Larsson LG. Myc represses differentiation-induced p21CIP1 expression via Miz-1-dependent interaction with the p21 core promoter. Oncogene. 2003;22:351–360. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka S. Elite and stochastic models for induced pluripotent stem cell generation. Nature. 2009;460:49–52. doi: 10.1038/nature08180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, SlukvinII R, Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.