Abstract

We studied the effect of prolonged activation of Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) signaling on 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D3)-action in the immortalized human prostate epithelial cell line RWPE1 and its K-Ras transformed clone RWPE2. 1,25(OH)2D3-treatment caused growth arrest and induced gene expression in both cell lines but the response was blunted in RWPE2 cells. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) levels were lower in RWPE2 cells but VDR over-expression did not increase vitamin D-mediated gene transcription in either cell line. In contrast, MAPK inhibition restored normal vitamin D transcriptional responses in RWPE2 cells and MAPK activation with constitutively active MEK1R4F reduced vitamin D-regulated transcription in RWPE1 cells. 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated transcription depends upon the VDR and its heterodimeric partner the Retinoid X Receptor (RXR) so we studied whether changes in the VDR-RXR transcription complex occur in response to MAPK activation. Mutation of putative phosphorylation sites in the Activation Function 1 (AF-1) domain (S32A, T82A) of RXRα restored 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated transactivation in RWPE2 cells. Mammalian two-hybrid and co-immunoprecipitation assays revealed a vitamin D-independent interaction between Steroid Receptor Coactivator-1 (SRC-1) and RXRα that was reduced by MAPK activation and was restored in RWPE2 cells by mutating S32 and T82 in the RXRα AF-1 domain. Our data show that a common contributor to cancer development, prolonged activation of MAPK signaling, impairs 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated transcription in prostate epithelial cells. This is due in part to the phosphorylation of critical amino acids in the RXRα AF-1 domain and impaired co-activator recruitment.

Keywords: Ras; mitogen activated protein kinase; transcription; growth arrest; 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D

Introduction

High vitamin D status has been proposed to protect against epithelial cell cancers of the colon, breast, and prostate (Ahonen et al, 2000; Giovannucci et al, 2006). The biologically active form of vitamin D, 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3) exerts anti-cancer activities through multiple mechanisms including inducing growth arrest, differentiation, and apoptosis as well as inhibiting angiogenesis (Fleet, 2008). Although the 1,25(OH)2D3-sensitive genes responsible for these actions are not known with certainty, activation of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) is required for the growth inhibitory effects of vitamin D in prostate cancer cell lines (Miller et al, 1995; Hedlund et al, 1996).

Ligand-bound VDR forms a heterodimer with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) and targets genes whose promoters contain vitamin D response elements (VDRE) to induce their transcription (Pike et al, 2007). Therefore, any conditions which interfere with the transcriptional activity of 1,25(OH)2D3 will impair its biological actions. With this in mind, there is evidence that molecular events associated with cancer progression may limit the chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic application of 1,25(OH)2D3 and its analogs. Resistance to the anti-carcinogenic effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 has been reported in various tumor cell models including skin (Sebag et al, 1992), breast cancer (Simboli-Campbell et al, 1996), acute myeloid leukemia (Wajchmann et al, 1996), and prostate cancer (Alagbala et al, 2007) cell lines.

Ras activating mutations are some of the most frequent somatic mutations in human cancers (Schubbert et al, 2007). Ras activation leads to the stimulation of the Mitogen Activiated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathway and contributes to cancer progression and development (Shields et al, 2000). In a Japanese cohort, Ki-Ras activating mutations were found in 20–30% of prostate cancer patients (Anwar et al, 1992). While Ki-Ras activating mutations in prostate cancer are less common in the U.S., abnormal activation of the Ras-Raf-MAPK signaling pathway is often detected in prostate cancer and Ras protein staining increases with the severity of the Gleason score of prostate cancer (Viola et al, 1986; Gioeli et al, 1999). Several groups have reported that MAPK activation modulates the transcriptional activity of 1,25(OH)2D3. Solomon et al. reported that in human keratinocytes over-expessing H-Ras, MAPK activation inhibits the vitamin D-induced transactivation of known target genes by causing phosphorylation of RXRα at serine 260 (S260) (Solomon et al, 1999). Similarly, Narayanan et al. compared 1,25(OH)2D3 transcriptional activity among MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells, MG-63 bone cells, and HeLa cervical cancer cells and found that only in cells with RXRα as the predominant isoform was 1,25(OH)2D3 action inhibited by MAPK activation (Narayanan et al, 2004). This suggests that although modulation of the Ras-Raf-MAPK pathway may change the sensitivity of cells to vitamin D, the impact of MAPK on vitamin D action may be cell-type specific.

To determine the mechanism by which constitutive MAPK activation alters vitamin D action in prostate epithelial cells, we utilized RWPE1 cells, an immortalized human prostate epithelial cell, and RWPE2, a Ki-Ras transformed version of RWPE1 with tumorigenic potential (Bello et al, 1997). Our experiments reveal that constitutive activation of MAPK signaling reduces vitamin D-mediated gene transcription and growth inhibition, phosphorylates RXRα, and alters the ability of the RXRα activation functional 1 (AF-1) domain to recruit the p160 transcriptional cofactors family member Steroid Receptor Coactivator-1 (SRC-1).

Materials and Methods

Supplies

Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Defined Keratinocyte-Serum Free Medium (SFM) was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and cell culture plasticware was from Corning-Costar (Cambridge, MA). 1, 25(OH)2 D3 was purchased from Biomol International (Plymouth Meeting, PA). The MEK inhibitor PD98059 was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). 1, 25(OH)2 D3 and PD98059 were dissolved in ethanol and DMSO, respectively and kept in light-protected vials at −80 °C until use.

Cell Culture

RWPE-1 and RWPE-2 cells were obtained from ATCC (CRL-11609 and CRL-11610, respectively) and used between passages 50 and 60. RWPE1 cells are HPV-18-immortalized human prostate epithelial cells while RWPE2 cells are v-Ki-Ras transformed RWPE1 cells (Rhim et al, 1994). Cells were maintained in Defined Keratinocyte-Serum Free medium (SFM) supplemented with growth factors (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and medium was replaced every other day.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were plated at 3 × 104 cells per 35 mm dish in Defined Keratinocyte-SFM medium. One day after plating, cells were treated with medium containing 0 (0.1% ethanol), 1, 10, or 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 (n=3). Media was changed every 2 days until the vehicle control plates of RWPE1 and RWPE2 reached 50% and 60% confluency, respectively. All cells were harvested by trypsin digestion, and live cells were counted on a hemocytometer using a trypan blue exclusion assay. The cell proliferation assay was conducted twice.

RNA isolation and real-time PCR analysis

RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells were plated in 6-well dishes (1.5 × 105 cells per well) and grown in Defined Keratinocyte-SFM medium until cells were 80% confluent. At this point, cells were treated with vehicle control (0.1% ethanol) or medium containing 1, 10, or 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 for 8 hours. Cells were harvested directly into TriReagent (1mL/well) (Molecular Research Center Inc., Cincinnati, OH), RNA was isolated, and reverse transcribed into cDNA (Fleet and Wood, 1999). cDNA samples were analyzed by real-time PCR analysis using the BioRad My iQ Realtime PCR system and the BioRad SYBR Green supermix (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Primers and annealing temperatures are reported elsewhere (Kovalenko et al, 2010). The cycle conditions for the PCR were 1 cycle of 3 minutes at 95 °C and 40 cycles of 30 seconds at 95 °C, 30 seconds at the annealing temperature, and 30 seconds at 72 °C. Expression of specific messages were determined from the threshold cycle (Ct) value using the method of 2−ΔΔCt described elsewhere (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Expression values for specific targets were normalized to GAPDH mRNA expression and data are expressed as arbitrary units. Gene expression studies were conducted twice with three replicate observations per treatment.

Plasmids

Firefly luciferase reporter constructs containing either three copies of the osteopontin VDRE linked to a minimal thymidine kinase promoter (VDRE3-tk-Luc) or the rat CYP24 promoter (−298 to +74 bp containing two functional VDREs) were obtained from Dr. Sunil Nagpal (Lilly Research Laboratory, IN) (Bettoun et al, 2003) and Dr. John L. Omdahl (University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM) (Kerry et al, 1996), respectively. The constitutively active mutant of MEK1 (MEK1R4F) was provided Dr. Melanie Cobb (University of Texas Southwest Medical Center, Dallas, TX) (Robbins et al, 1993). The RXRα expression vector (pCMX-RXRα) was from Dr. Richard Kremer (McGill University, Canada) (Solomon et al, 1999). Vectors used in the mammalian two hybrid assay, i.e. pRF-Luc, pGal4-mouse RXRα ligand binding domain (LBD), pVP16-rat VDR-LBD, pGal4-SRC-1 and pVP16-mouse RXRα-LBD were also provided by Dr. Sunil Nagpal (Bettoun et al, 2003).

Two additional plasmids for two-hybrid assays were constructed in our lab. A pGal4-RXRα AF-1 vector was constructed in multiple steps. First, a 420 bp PCR product encoding the first 135 amino acids of the human RXRα (i.e. the AF-1 domain) was obtained by PCR using the pCMX-RXRα vector as a template using TaqPlus Precision polymerase mixture (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and PCR primers (forward 5′-GAATTCATGGACACCAAACATTTCCTGCCGC-3′ and reverse 5′-AAGCTTGCGCAGATGTGCTTGGTGAAGGAAGCC-3′). PCR fragments were subcloned into the pCR4-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to yield pCR4-TOPO-RXRα AF-1. Next, the AF-1 domain fragment was removed from pCR4-TOPO-RXRα AF-1 by digestion with ECoRI and Hind III (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and the insert was ligated into the pM vector downstream from the Gal4 DNA binding domain (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). To build the pVP16-SRC-1 construct, a 4.2 kb fragment encoding the full length of SRC-1 was obtained by digesting pGal4-SRC-1 with Sma I and Xba I sequentially. The pVP16 vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) was first digested with ECoRI and then the cut ends were filled using Klenow DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The pVP16 vector was next digested with Xba I and the SRC-1 fragment was ligated into that site. The sequences of all vectors obtained by PCR cloning or traditional subcloning were confirmed by direct sequencing at the Purdue Genomics Facility.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Mutant versions of the RXRα expression and mammalian two hybrid assay vectors were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of the parent vectors using the QuikChange XL mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The specific changes induced were Tyrosine 249 to Alanine (Y249A), Serine 260 to Alanine (S260A), Serine 32 to Alanine (S32A), Threonine 82 to Alanine (T82A). The sequence of the RXRα mutants was verified by direct sequencing.

Transient transfection and Luciferase assay

RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells were plated in 24-well plates at the density of 2.5 × 104 cells per well. When cells reached 40% confluency, they were transfected using 1μl lipofectamine, 2.5 μl plus reagents (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 250 ng of pVDRE3-tk-Luc reporter gene or rat CYP24 reporter gene and 1 ng of CMV-Renilla vector (Promega, Madison WI) as a transfection efficiency control. Six hours after transfection, cells were fed with Defined Keratinocyte-SFM medium and cultured for 12 hours. Cells were then treated with vehicle or 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 containing medium for 24 hours. Luciferase activity was determined using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) with a luminometer (TD-20/20, Turner Design). The value is expressed as the ratio of firefly to renilla fluorescence. To examine the role of ERK1/2 in VDRE reporter gene activity, cells were co-transfected with 250 ng of vector expressing a constitutively active MEK1 protein or pre-treated with 10 μM PD98059 for 30 minutes before treatment with 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3. To assess the role of RXRα mutants in 1,25(OH)2D3 transcriptional activity, 1 μg of RXRα mutant vectors (S32A, T82A, Y249A, S260A) were co-transfected. At least two independent experiments were performed for each study and each experiment used at least four replicates per treatment.

Immunodetection of VDR, RXRα, ERK1/2

Whole cell extracts were prepared from 80% confluent cells using the Active Motif Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). Total protein content of samples was determined using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins (50 μg) were resolved on 12.5% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to PVDF membranes and probed with rat anti-chick VDR antibody (Ab9A7, Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO), rabbit anti-RXRα antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit anti-ERK1/2 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), rabbit anti-phospho ERK1/2 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), or mouse anti-beta actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). With the exception of VDR, the membranes were incubated overnight a 1:2,000 dilution of primary antibody prepared in blocking solution followed by a 1:5,000 dilution of horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Specific binding was detected using the Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL). VDR immunodetection was carried out using three antibodies: rat anti-chick VDR antibody Ab9A7 (1:2,000), rabbit anti-rat IgG (1:5,000 dilution, Chemicon, Temecula, CA), and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, (1:20,000 dilution, Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The membrane was incubated with each antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Specific binding was detected using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL). For all membranes chemiluminescence was detected by exposure of the membranes to X-ray Kodak film. The band intensities were recorded by densitometry using a Bio-Rad imaging densitometer and quantified using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The quantity of proteins of interest was standardized for each sample using beta-actin protein levels.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were done as described previously by our group (Cui et al, 2009). Quantification of VDR and RXRa ChIP results from the CYP24 promoter (−252 to −51 bp) and the TRPV6 promoter (−4.3 kb region) were determined from the threshold cycle (Ct) value using the method of 2−ΔΔCt described elsewhere (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Expression values for specific targets were normalized to imput DNA Ct levels and data are expressed as arbitrary units.

Immunoprecipitation of phosphorylated RXRα and co-immunoprecipitation of SRC-1

32P labeling of RXRα

RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells were washed with phosphate-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium. Cells were incubated with phosphate-free DMEM supplemented with 0.5 mCi [32P]-orthophosphate (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH). Three hours later, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and cell lysates were collected (lysis buffer: 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.2 mM Sodium orthovanadate, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablet per 50 ml; (Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland)) and their protein levels quantified using the BioRad protein assay. Human RXRα was immunoprecipitated from 100 μg of whole cell extract using 2 μg of a polyclonal anti-human RXRα antibody (AbD Serotec, #AHP1116, Raleigh, NC) incubated at 4°C overnight. Immune complexes were collected with a 50% slurry of Fastflow protein G (Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburg, PA) in IP buffer (2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris HCl, 1%Triton X, pH=8) for 1 h at 4°C. After washing the beads with IP buffer containing 0.10% SDS, the proteins were released from the bead by incubating the samples with Laemmli buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 1% β-mercaptoethanol, 12 mM EDTA, 0.02% bromophenol blue pH=6.8) for 10 min at 95°C. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated on a 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel (BioRad, Hercules CA) at 120 V for 2 h, dried for 1 h, and analyzed by autoradiography with a Perkin Elmer Cyclone phosphoimager (Downers Grove, IL).

Co-immunoprecipitation of SRC-1 with RXRα

Whole cell extracts were prepared from 80% confluent cells using the Active Motif Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). Total protein content of samples was determined using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). 10 μg of rabbit anti-RXRα antibody (sc-553x, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was incubated with 50 μl Dynabeads-Protein G (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in Citrate-Phosphate buffer (25 mM Citric Acid, 50 mM Na2HPO4, pH 5.0) for 2 hours at room temperature. The mixture was then washed three times with 0.1% Tween-20 Citrate-Phosphate buffer and incubated with 250 μg whole cell extract overnight at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitates were washed 4-times in PBS, boiled for 5 minutes, resolved on 7.5 % SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Blots were probed overnight with a second anti-RXRα (1:2000 dilution) (sc-774x, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), monoclonal anti-phosphoserine, anti-phosphothreonine (1:1,000 dilution) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) or anti-SRC-1 antibodies (1:2000 dilution) (Affinity BioReagents Inc., Golden, Co). After incubation with a 1:5,000 dilution of horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), the specific binding was detected using Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Mammalian two hybrid assay

A mammalian two hybrid assay was used to study the interaction between VDR and RXRα or the coactivator SRC-1 as well as between and RXRα fragments and SRC-1. RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells were cultured in 24-well plates as described above. 250 ng of luciferase reporter vector pFR-Luc (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), 125 ng of target and prey protein expressing vectors, and 1 ng of CMV-Renilla vector were used to transfect cells along with 2μl Lipofectamine and 5 μl plus reagent per well. RWPE1 and RWPE2 express high levels of VDR and RXRα naturally so no third protein is added other than target and prey proteins (e.g. no additional VDR was expressed when SRC-1 by RXRα interactions were studied). 24 hours after transfection cells were treated with vehicle or 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 for 24 hours and the dual Luciferase assay was done. To assess the role of specific amino acid residues in RXRα in the interaction with SRC-1, various mutants of pVP16-RXRα-LBD (S260A) and Gal4-RXRα AF-1 (S32A, T82A) were compared to wild-type RXRα.

Statistical analysis

Data is reported as the means ± SEM. When the plots of predicted values versus residuals demonstrated that the data were not normally distributed a log transformation was conducted before the statistical analysis. The treatment effects in each experiment were compared by one- or two-way ANOVA using the SAS statistical software package (SAS 8.0 Cary, NC). Pairwise comparisons were conducted when appropriate using Fisher’s Protected LSD. Differences between means were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

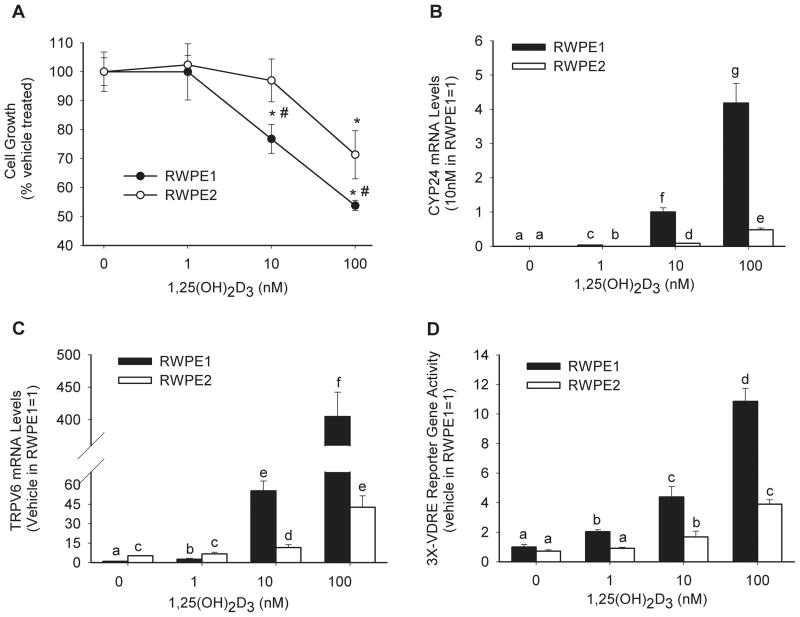

1,25(OH)2D3-induced growth suppression and transcriptional activation are blunted by Ki-Ras transformation

1,25(OH)2D3 dose-dependently suppresses the growth of both RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells (Figure 1A). However, Ki-Ras transformed RWPE2 cells required 10-fold more 1,25(OH)2D3 than the parental line RWPE1 (p< 0.05) to reach a similar level of growth-arrest. 1,25(OH)2D3-induced accumulation of several vitamin D target genes were significantly suppressed in RWPE2 compared to RWPE1: CYP24 (Figure 1B), TRPV6 (Figure 1C), p21, TXNRD1, and P2RY2 mRNA (by 90%, 90%, 46%, 30%, and 80%, respectively at the dose of 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3). Similarly, 1,25(OH)2D3-induced activation of a luciferase reporter gene construct controlled by a promoter with three copies of the osteopontin VDRE (3X-VDRE) was inhibited by 60% at the 100 nM dose in the Ki-Ras transformed cells (p< 0.05, Figure 1D). Similar results were obtained using a −298 to +74 bp rat CYP24 promoter-luciferase reporter gene construct containing two functional VDREs (data not shown). This suggests that the blunted growth inhibitory response to 1,25(OH)2D3 in RWPE2 is at least partially due to decreased VDR-mediated transcriptional activity.

Figure 1. 1,25(OH)2D3-induced actions are blunted in RWPE2 cells.

(A) Cell Growth; Low density cultures of RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells were treated for 5 days with 0–100 nM of 1,25(OH)2D3. Live cells were counted using a trypan blue exclusion assay when vehicle-treated cells reached 50–60% confluency. Data are expressed relative to the value for the non-treated RWPE1 or RPWE2 cells (100%) as mean ± SEM. (n=3 per group). * Significantly different from vehicle-treated (p<0.05). # Significantly different from RWPE2 at the same 1,25(OH)2D3 dose (p< 0.05). (B and C) mRNA Level; 80% confluent cultures of RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells were treated with 0–100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 for 8 hours. Total RNA was isolated and analyzed by real time-PCR for CYP24, TRPV6 and GAPDH mRNA expression. CYP24 and TRPV6 mRNA levels were normalized to GAPDH expression within each sample. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3 per group). Bars with different letter superscripts are significantly different (p< 0.05). (D) Promoter Activation; 40% confluent cultures of RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells were transfected with 250 ng of a minimal 3X-VDRE promoter-firefly luciferase reporter gene and 1 ng of a CMV promoter-renilla luciferase reporter gene. 24 hours later transfected cells were incubated with 0–100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 for 24 hours. Firefly luciferase was normalized to renilla luciferase levels and data are expressed as fold change above vehicle-treated control (mean ± SEM, n=6 per group). Bars with different letter superscripts are significantly different (p< 0.05).

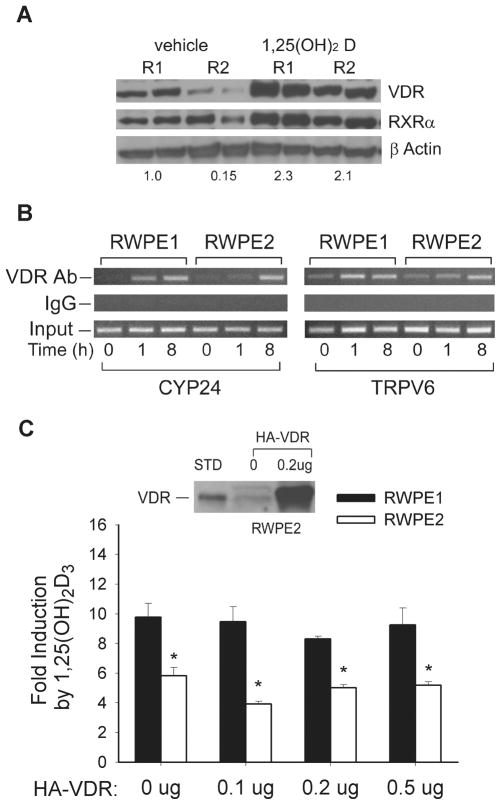

Low VDR and RXRα protein levels do not account for the blunted response of Ki-Ras-transformed RWPE2 cells to 1,25(OH)2D3

Real-time PCR analysis showed that only RXRα and β were expressed in RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells and that RXRα was the predominant form (data not shown). Neither RXRα mRNA (data not shown) nor protein levels were different between RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells. In contrast, both VDR mRNA (56% lower, data not shown) and VDR protein levels were significantly lower in RWPE2 cells (0 h time, Figure 2A). However, treatment of RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells with 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 resulted in equal accumulation of VDR at 8 h post-treatment (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. The role of VDR level on the decreased response of RWPE2 cells to 1,25(OH)2D3.

(A) Western blot analysis of VDR and RXRα; 80% confluent cultures of RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells were treated with 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 for 0 or 8 h. Whole cell extracts were isolated and analyzed for VDR and RXRα protein. was used as a loading control. Values under the picture represent the β-actin-normalized level of VDR protein, (B) Representative gel image of ChIP analysis for 1,25(OH)2D3-induced VDR binding to the CYP24 and TRPV6 promoters; RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells were treated with 10nM 1,25(OH)2D3 for 0, 1, or 8 h. After cross-linking and DNA fragmentation cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies to VDR or IgG. DNA from the immunoprecipitates was isolated and amplified by qPCR using the appropriate primers. (C) Impact of VDR over-expression on vitamin D-induced promoter activity; Insert panel: 0.2 μg of HA-VDR expression vector was transiently transfected into proliferating RWPE2 and VDR protein levels were assessed by Western blot analysis. Lower panel: RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells were transfected with 0–0.5 μg HA-VDR expression vector, 250 ng of a minimal 3X-VDRE promoter-firefly luciferase reporter gene, and 1 ng of a CMV promoter-renilla luciferase reporter gene. 18 h later, transfected cells were incubated with 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 for 24 hours. Firefly luciferase was normalized to renilla luciferase levels and data are expressed as mean fold changes relative to the vehicle treated control (mean ± SEM, n=6 per group). * Significantly different from RWPE1 at the same 1,25(OH)2D3 dose (p<0.05).

ChIP analysis demonstrated that association of VDR with the CYP24 (proximal promoter region) and TRPV6 (−4.3 kb region) gene promoters was observed by 1 h after treatment with 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 in both cell lines but was lower in RWPE2 cells (the input-normalized VDR ChIP value for RWPE2 was 45% lower than the value for RWPE1 based on qPCR, representative gel image Figure 2B). However, an equal amount of VDR was present on these promoters in RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells after 8 hours treatment based on qPCR and input-normalized VDR ChIP values.

To further investigate the role of VDR level in the resistance to 1,25(OH)2D3 in RWPE2, we transiently transfected RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells with a VDR expression vector and performed a reporter gene assay using the 3X VDRE-luciferase reporter gene construct. Although VDR expression was strongly increased (Figure 2C insert) this did not restore the response of RWPE2 cells to 1,25(OH)2D3 (Figure 2C graph).

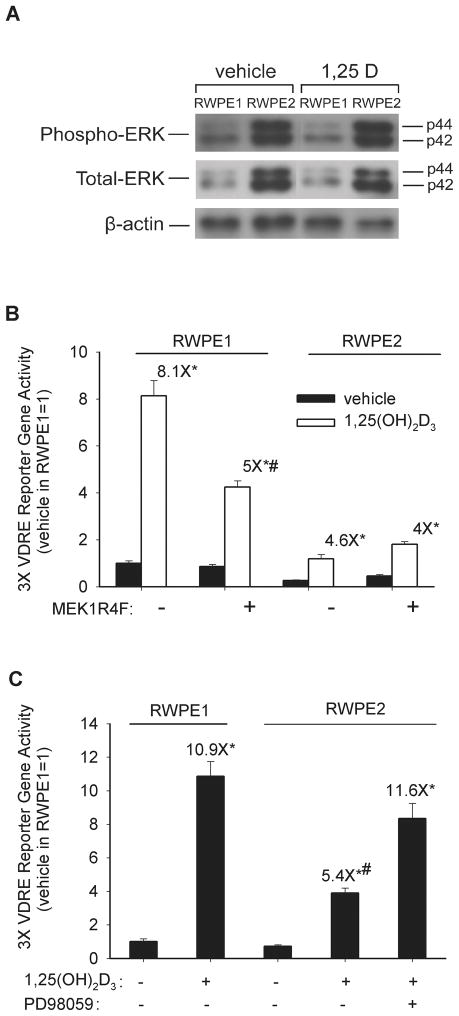

Activated MAPK inhibits 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated promoter activity

Both the total and phosphorylated forms of the MAPK family members ERK1 and ERK2 were up-regulated in Ki-Ras transformed RWPE2 cells (Figure 3A), suggesting prolonged MAPK activation could contribute to the blunted response of RWPE2 cells to 1,25(OH)2D3. We tested this hypothesis in two ways. First, activation of MAPK signaling with transient transfection of a constitutively active MEK1 mutant (MEK1R4F) significantly suppressed 1,25(OH)2D3-induced transcriptional activity in RWPE1 cells (Figure 3B) but not in RWPE2 where the MAPK pathway is already activated. Conversely, inhibition of MEK1 activity with PD98059 restored 1,25(OH)2D3-induced transcriptional activity in Ki-Ras transformed RWPE2 cells to a level comparable to that seen in RWPE1 cells (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Activated MAPK activity reduces the response to 1,25(OH)2D3 in prostate epithelial cells.

(A) ERK1 (p42) and ERK2 (p44) are activated in RWPE2 cells. Proliferating RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells were treated with vehicle or 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 for 8 h. Whole cell extracts were analyzed for total and phospho/active ERK1 and ERK2 as well as β-actin by Western Blot analysis. (B) Constitutively active MEK1 (MEK1R4F) reduces the induction of a 3X-VDRE promoter-firefly luciferase reporter gene by 1,25(OH)2D3 in RWPE1. RWPE1 cells were treated with 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 for 24 hours after transfection with 250 ng constitutively active MEK1 (MEK1R4F) or its empty vector control along with 250 ng 3X-VDRE promoter-firefly luciferase reporter gene and 1 ng of a CMV promoter-renilla luciferase control gene. Firefly luciferase was normalized to renilla luciferase levels and data are expressed as mean fold changes relative to vehicle-treated control (mean ± SEM, n=6 per group). * Significantly different from vehicle-treated control (p<0.05). # Fold change significantly different from empty vector-transfected cell in same line (p<0.05). (C) MEK1/2 inhibition restores the 1,25(OH)2D3 transcriptional response to RWPE2 cells. RWPE2 cells were transfected with the 3X-VDRE-luciferase reporter gene then treated with vehicle or 10 uM PD98059 in the presence or absence of 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 for 24 hours. 1,25(OH)2D3-treated RWPE1 cells are shown as a reference. Firefly luciferase was normalized to renilla luciferase levels and data are expressed as mean fold changes relative to vehicle-treated control (mean ± SEM, n=6 per group). * Significantly different from vehicle-treated control (p<0.05). # Significantly different from the fold change in 1,25(OH)2D3-treated RWPE1 cells (p<0.05).

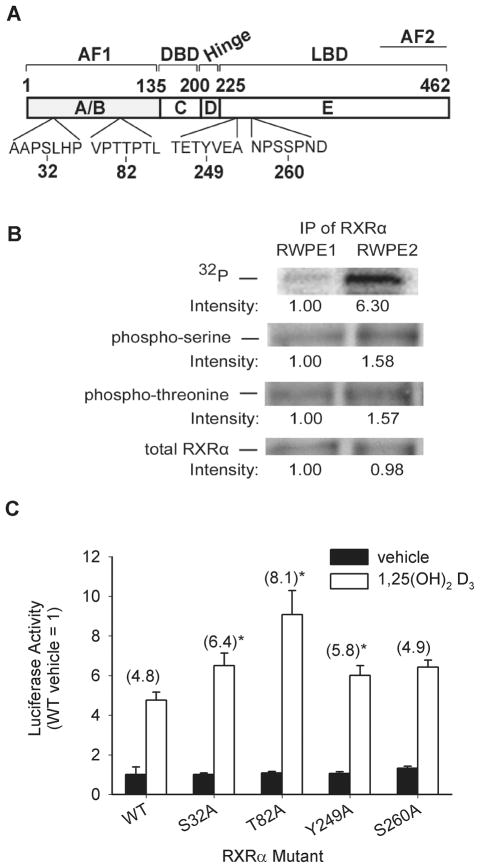

RXRα phosphorylation suppresses 1,25(OH)2D3-induced transcriptional activity

In vitro and cell-free studies have previously shown that four amino acid residues in RXRα can be phosphorylated: serine 32 (S32), threonine 82 (T82), tyrosine 249 (Y249), and serine 260 (S260) (Solomon et al, 1999; Lee et al, 2000; Adam-Stitah et al, 1999) (Figure 4A). We used two independent approaches to determine if RXRα phosphorylation is increased in Ras-transformed RWPE2 cells. First, 32P-labeling shows that RXRα is a phosphoprotein in both RWPE cell lines and that total RXRα phosphorylation is significantly higher in RWPE2 cells (Figure 4B). Second, immunoprecipitation of RXRα and reprobing with anti-phosphoserine and threonine antibodies confirmed that RXRα phosphorylation state is significantly increased in Ki-Ras transformed RWPE2 cells (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. RXRα phosphorylation limits 1,25(OH)2D3-regulated gene expression in RWPE2 cells.

(A) Schematic representation of the functional domains and the major phosphorylation sites previously identified in human RXRα. (B) Phosphorylation RXRα. Phosphorylated RXR was examined in two ways. Following incubation of RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells with 32P-orthophosphate, RXRα was immunoprecipitated from equal amounts of whole cell extracts from the two cells using an anti-RXRα antibody. In a separate experiment, immunoprecipitated proteins were probed for phospho-serine residues, phospho-threonine residues, and total RXRα by Western Blot analysis. Bands were quantified by densitometry. (C) Mutation of putative phosphorylation sites in RXRα influence 1,25(OH)2D3-regulated transcription in RWPE2. Proliferating RWPE2 cells were transfected with 1 μg wild-type (WT) or mutant RXRα expression vectors (S32A, T82A, Y249A, S260A) along with 250 ng 3X-VDRE promoter-firefly luciferase reporter gene and 1 ng of a CMV promoter-renilla luciferase control gene. 12 hours later cells were treated with 0 or 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 for 24 hours. Firefly luciferase was normalized to renilla luciferase levels and data are expressed as fold changes relative to the vehicle-treated control (mean ± SEM, n=6 per group). * Significantly different from the fold 1,25(OH)2D3 induction in WT RXRα vector-transfected cells (p<0.05).

To further investigate the role that RXRα phosphorylation could play in 1,25(OH)2D3-regulated gene transcription, S32, T82, Y249 and S260 were individually mutated to alanine (A) and the influence of these RXRα mutants on induction of the 3X-VDRE-luciferase reporter gene by 1,25(OH)2D3 was studied in RWPE2 cells. Western blot analysis showed that equal amounts of RXRα were expressed when cells were transfected with the WT, S32A, T82A, Y249A, or S260A RXRα expression vectors (data not shown). Transfection of wild-type RXRα into RWPE2 had no effect on VDR-dependent transcriptional activity compared to the empty vector alone (4.7-fold induction with 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment, data not shown). S32A (6.4-fold induction), T82A (8.1-fold), and Y249A (5.8-fold) mutants each increased 1,25(OH)2D3-induced transcriptional activity in RWPE2. In contrast, basal reporter gene expression was increased significantly in cells transfected with the S260A mutant, and only a modest change was observed for vitamin D-induced reporter gene activity (4.9-fold, Figure 4C). These data support the hypothesis that phosphorylation of RXRα at both the AF-1 domain (S32A, T82A) and in the LBD (Y249A, S260) negatively regulates 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated transcription.

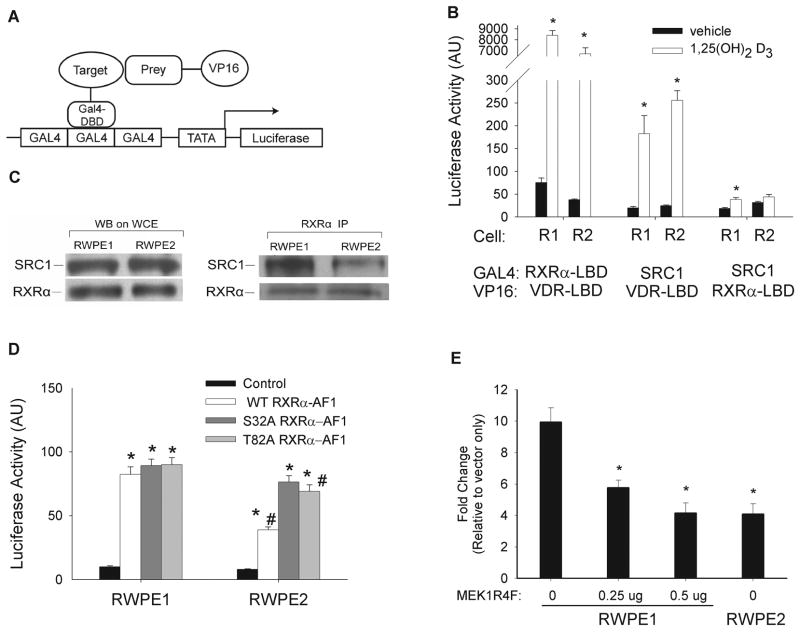

The interaction between SRC-1 and RXRα is impaired in Ki-Ras transformed RWPE2 cells

Using a mammalian two-hybrid assay, we explored the impact of constitutive MAPK activation and RXRα phosphorylation on interactions between RXRα with VDR or with the p160 co-activator family member, SRC-1. As expected, 1,25(OH)2D3-treatment stimulated interactions between RXRα-LBD and VDR-LBD (> 100-fold), SRC-1 and VDR-LBD (9.5-fold), and to a lesser extent, SRC-1 and RXRα-LBD (2.6-fold) in RWPE1 cells (Figure 5B). Although the basal interaction was 50% lower between RXRα-LBD and the VDR-LBD in RWPE2 cells, the fold induction due to 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment was higher in RWPE2 cells (178-fold vs. 111-fold, respectively). The 1,25(OH)2D3-induced interaction between the VDR-LBD and SRC-1 was not altered significantly in RWPE2 cells (9.3 fold in RWPE1 vs. 10.4 fold in RWPE2). The small, vitamin D-induced interaction between SRC-1 and the RXRα-LBD was reduced by 32% in RWPE2 cells as a result of increased reporter gene activity in the vehicle treated control (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. An interaction between SRC-1 and RXRα is impaired in RWPE2 cells.

(A) Schematic representation of the mammalian two hybrid assay system. (B) Interactions between VDR-ligand binding domain (LBD), RXRα-LBD, and SRC-1; RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells were transfected with 250 ng of the Gal4 responsive pRF-Luc vector, 125 ng of target-expressing vector (pGal4-RXRα-LBD or pGal4-SRC-1), 125 ng of prey-expressing vector (pVP16-VDR-LBD or pVP16-RXRα-LBD), and 1 ng CMV promoter-renilla luciferase control vector. 18 hours after transfection cells were treated with 0 or 100 nM 1,25(OH)2D3 for 24 hours. Firefly luciferase was measured and normalized to renilla luciferase levels (mean ± SEM, n=4 per group). * Significantly different from the vehicle control. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation of SRC-1 with RXRα is reduced in RWPE2; Whole cell extracts were prepared from untreated, proliferating RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells. RXRα was immunoprecipitated using an anti-RXRα antibody after which total RXRα and SRC-1 protein was determined in the immunoprecipitate by Western blot. (D) Mutation of putative phosphorylation sites in the AF-1 domain of RXRα influence the SRC-1-RXRα AF-1 interaction. Proliferating RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells were transfected with 250 ng of pRF-Luc vector, 125 ng of VP16-SRC-1 and 125 ng of empty vector (control), WT, or mutant (S32A, T82A) Gal4-mouse RXRα AF-1 expression vectors. 24 hours later reporter gene activity was measured. Firefly luciferase level was measured and normalized to renilla luciferase levels (mean ± SEM, n=6 per group). * Significantly different from the empty GAL4 vector control (p<0.05). # Significantly different from the RWPE1 result. (E) Constitutive MAPK activation reduces the interaction between SRC-1 and RXRα AF-1 domain in RWPE1 cells. Cells were transfected with 250 ng of pRF-Luc vector, 125 ng of VP16-SRC-1, and 125 ng of empty GAL4 vector or WT GAL4-RXRα AF-1 vector, along with 0, 0.25, or 0.5 μg of the constitutively active MEK1R4F vector. The total amount of plasmid DNA was kept constant in each transfection by adding empty MEK1R4F vector to the 0 and 0.25 μg groups. 24 hours later reporter gene activity was measured. Firefly luciferase level was normalized to renilla luciferase level and data are expressed as fold induction relative to empty vector control (mean ± SEM, n=6 per group). * Significantly different from the fold induction in RWPE1 without MEK1R4F transfection (p<0.05).

We observed a significant interaction between the RXRα AF-1 domain and SRC-1 in RWPE1 that was independent of vitamin D treatment (8.2-fold above the empty GAL4 vector control). This interaction was decreased by 43% in RWPE2 cells (Figure 5D) suggesting that it is sensitive to MAPK-dependent phosphorylation events. Consistent with this observation, we found that SRC-1 co-immunoprecipitated with RXRα from extracts of RWPE1 cells and this association was lower in both the total cell lysate (Figure 5C) and the nuclear fraction (data not shown) of Ki-Ras transformed RWPE2 cells with high MAPK activity. This was not due to lower levels of SRC-1 protein in RWPE2 cells; total SRC-1 levels were not different between RWPE1 and RWPE2 cells (Figure 5C).

To test the role of the putative RXRα phosphorylation sites in Ras-mediated suppression of SRC-1-RXRα interactions, mammalian two-hybrid assays were conducted using mutant human RXRα AF-1 (S32A and T82A) and mouse RXRα-LBD constructs (S265A, equivalent to S260 in human). Consistent with the data in Figure 4C, the S265A mutant in mouse RXRα had no impact on the 1,25(OH)2D3-dependent interaction between SRC-1 and the RXRα-LBD (data not shown). In contrast, the S32A mutation in the RXRα AF-1 domain completely rescued the impaired 1,25(OH)2D3-independent interaction between the RXRα AF-1 and SRC-1 in RWPE2 cells while the T82A mutation partially recovered this response (Figure 5D). This suggests that phosphorylation of RXRα AF-1 at these residues is normally repressive. Consistent with this hypothesis, activation of MAPK with a constitutively active MEK1 mutant (MEK1R4F) reduced the interaction between RXRα AF-1 and SRC-1 in RWPE1 cells to the level normally seen in RWPE2 cells (Figure 5E). Taken together, these data suggest that phosphorylation of RXRα AF-1 by activated MAPK inhibits the interaction between SRC-1 and RXRα.

Discussion

Our data show that prolonged, constitutive activation of MAPK signaling, whether in Ki-Ras transformed cells or cells transiently transfected with a constitutively active MEK1 mutant, impairs the genomic actions of 1,25(OH)2D3 in human prostate epithelial cells. Constitutive activation of MAPK signaling has previously been reported to have a negative effect on 1,25(OH)2D3-induced gene transcription in some, but not all reports. For example, while MAPK activity is essential for 1,25(OH)2D3-induced transactivation in MG-63 cells, HeLa cells (Narayanan et al, 2004), and COS-1 kidney cells (Dwivedi et al, 2002), it impairs vitamin D responsiveness in MC3T3-E1 cells (Narayanan et al, 2004), and H-Ras over-expressing keratinocytes (Solomon et al, 1999). Some of these inconsistencies may be due to differences in the intensity and duration of the MAPK signal between normal (low and transient) and Ras-transformed (high and persistent) cells (Roovers and Assoian, 2000). Data from our group using Caco-2 cells supports this hypothesis; transient activation of MAPK signaling with EGF enhances 1,25(OH)2D3-induced gene transcription (Cui et al, 2009) while prolonged activation due to transfection of cells with constitutively active MEK1 impairs it (unpublished data). We have tested several hypotheses to explain the mechanism by which prolonged, constitutive activation of MAPK signaling can impair vitamin D signaling in prostate epithelial cells.

Although we observed that VDR levels are reduced in the Ras-transformed RWPE2 cells, several lines of evidence suggest that this is not the primary cause of vitamin D resistance observed in these cells. First, and most critically, providing RWPE2 cells with additional VDR did not reverse their blunted transcriptional response to 1,25(OH)2D3. In addition, while TRPV6 induction by 1,25(OH)2D3 is impaired in RWPE2 cells, our previous data on 1,25(OH)2D3-induced TRPV6 induction in mouse intestine showed that 50% lower VDR levels in intestine do not alter this effect (Song and Fleet, 2007). Finally, VDR is stabilized equally on the 1,25(OH)2D3-responsive CYP24 and TRPV6 gene promoters in both K-Ras transformed and non-transformed cells suggesting low VDR content doesn’t limit the recruitment of VDR to promoters during the timeframe of our reporter gene assays.

Narayanan et al. previously suggested that the predominant RXR isoform within a cell defines whether activation of MAPK signaling enhances or inhibits 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated gene transcription (Narayanan et al, 2004). Like Solomon et al. (Solomon et al, 1999), they determined that RXRα was the target of MAPK-mediated inhibition; our data are consistent with these reports. Although RXRs are obligatory partners for class II steroid hormone receptors (Brelivet et al, 2004), RXR has traditionally been viewed as a silent partner in the context of VDR, RAR and TR-dependent transcription because RXR does not bind ligand when participating in these heterodimer complexes (Forman et al, 1995). However, Bettoun et al.(Bettoun et al, 2003) found that RXRα can recruit essential coactivators to the VDR-RXR heterodimer through its AF-2 domain where it may then transfer them to VDR. In addition, others have found that RXR is responsible for nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of both the unliganded and ligand-bound VDR (Prufer et al, 2002). The “active partner” model for RXR has been reinforced through studies where RXRα phosphorylation at specific amino acid residues influences co-activator recruitment and nuclear import (Kumar and Thompson, 2003).

Using a variety of cell-free approaches, researchers have found that RXRα can be phosphorylated by several MAPK family members (e.g. ERK1/2, SEK1 and JNK) at sites that reside in the N-terminal AF-1 (S22, S32, S56, S70, T82), and C-terminal LBD domains (Y249, S260) (Solomon et al, 1999; Adam-Stitah et al, 1999; Lee et al, 2000; Bastien et al, 2002; Mann et al, 2005; Bruck et al, 2005; Zimmerman et al, 2006). Our data confirm and extend these observations. We found that RXRα is a phosphoprotein whose total level of phosphorylation, as well as specific phosphorylation at serine and threonine residues, is increased in Ki-Ras transformed cells (Figure 4B). Mutation analysis suggests that phosphorylation at several of these sites in RXRα including S32, T82, and Y249 inhibits ligand-dependent transactivation for various class II receptor partners (Mann et al, 2005; Lee et al, 2000).

The impact of Ras transformation on RXRα phosphorylation and vitamin D action was first studied by Solomon et al. (Solomon et al, 1999). They reported that phosphorylation of S260 in RXRα by MAPK suppresses 1,25(OH)2D3-induced transactivation in H-Ras-overexpressing keratinocytes (Solomon et al, 1999). More recently this group has shown that phoshorylation at S260 impairs recruitment of DRIP205 and other co-activators to the VDR-RXR heterodimer (Macoritto et al, 2008). In hepatocellular carcinoma cells phosphorylation of RXRα at S260 also delays nuclear export and RXRα degradation as well as inhibits RAR-dependent transcription (Matsushima-Nishiwaki et al, 2001). Although we did not directly measure the phosphorylation at these specific amino acid residues (S32, T82, Y249, and S260), we found that S32 and T82 in the AF-1 domain are important for 1,25(OH)2D3-induced gene expression. In contrast, mutation of S260 had a lesser impact on 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated reporter gene activation in prostate epithelial cells. Our observation that S260 in RXRα has a minor role in mediating the effect of Ras on 1,25(OH)2D3 action could be a reflection of the cell system used (prostate epithelial cells versus keratinocytes) or differences in the function or distribution between K-Ras and H-Ras.

We found that the co-activator SRC-1 interacts with RXRα through the AF-1 domain (Figure 5) but that this interaction is not dependent on the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3. SRC-1 binding to RXRα is reduced by over 40% in RWPE2 cells and our mutation analysis suggests that this is because of phosphorylation in the AF-1 domain at S32 and T82. To our knowledge, this is the first report to show that the RXRα AF-1 domain interacts with SRC-1 and that this interaction may be blocked by the AF-1 domain phosphorylation state. However, the points of interaction between SRC-1 and the AF-1 domain, as well as how this binding contributes to the transcriptional activity of RXRα heterodimeric partners like VDR, are not clear at this time. Several groups have reported that the AF-1 and AF-2 domains of nuclear receptors might work synergistically to recruit co-activators (Benecke et al, 2000) (Hittelman et al, 1999). It is interesting to note that VDR has no N-terminal AF-1 domain therefore it directly interacts with SRC-1 only through its AF-2 domain (McInerney et al, 1998). We postulate that the RXRα AF-1 domain works synergistically with the AF-2 domain of ligand-occupied VDR to recruit SRC-1. More studies are required to test this hypothesis. In addition, our current data do not exclude the potential for involvement of other proteins in MAPK-induced resistance to vitamin D (e.g. phosphorylation of co-activators like SRC-1, p300, or mediator 1, as well as VDR). Future studies are needed to examine these alternate hypotheses.

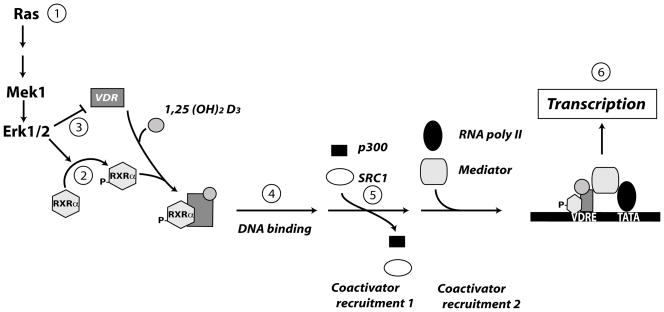

In summary, our data demonstrate that constitutive Ras-MAPK activation impairs 1,25(OH)2D3-regulated gene transcription and that this may be due to phosphorylation of the RXRα AF-1 domain and impaired recruitment of the transcriptional cofactor SRC-1. A model describing the effect of constitutive MAPK signaling on vitamin D-mediated gene transcription is presented in Figure 6. Our data highlights the importance of RXRα as an active player in the anticancer effects of vitamin D. In addition, our data are part of a growing body of literature that indicates the process of carcinogenesis may negatively influence the cellular response to vitamin D metabolites (Chen et al, 2003; Zhuang et al, 1997). Future studies should examine whether Ras-activating mutations can impair the protective effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 in animal models of prostate cancer and also in cancers where these mutations are more common (i.e. colon cancer where 60% of tumors may have a Ras activating mutation).

Figure 6. A model summarizing the impact of constitutive MEK activation on vitamin D regulated gene transcription in prostate epithelial cells.

Constitutive activation of Ras or MAPK signaling is seen in prostate cancer (1) and this leads to phosphorylation of RXRα (2) as well as reduced VDR protein levels (3) in prostate epithelial cells. Reduced VDR levels may account for the delayed binding of VDR to DNA seen in the ChIP assay (4). Co-immunoprecipitation assays and two-hybrid assay reveal that vitamin D-independent binding of the essential co-activator SRC-1 to RXRα is reduced (5). Although recruitment of the mediator complex is critical for vitamin D regulated gene expression, it is not clear whether MAPK activation-mediated RXRα phosphorylation influences this step. The cumulative effect of the changes outlined is a reduction in 1,25(OH)2D3-regulated gene transcription in transformed prostate epithelial cells (6).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Sunil Nagpal, Dr. John Omdahl, Dr. Melanie Cobb and Dr. Richard Kremer for providing reagents.

This work was supported by funds from National Institutes of Health award CA101113 to J.C.F.

Literature Cited

- Adam-Stitah S, Penna L, Chambon P, Rochette-Egly C. Hyperphosphorylation of the retinoid X receptor alpha by activated c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18932–18941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahonen MH, Tenkanen L, Teppo L, Hakama M, Tuohimaa P. Prostate cancer risk and prediagnostic serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels (Finland) Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:847–852. doi: 10.1023/a:1008923802001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagbala AA, Moser MT, Johnson CS, Trump DL, Foster BA. Characterization of Vitamin D insensitive prostate cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:712–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwar K, Nakakuki K, Shiraishi T, Naiki H, Yatani R, Inuzuka M. Presence of ras oncogene mutations and human papillomavirus DNA in human prostate carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5991–5996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien J, Adam-Stitah S, Plassat JL, Chambon P, Rochette-Egly C. The phosphorylation site located in the A region of retinoic X receptor alpha is required for the antiproliferative effect of retinoic acid (RA) and the activation of RA target genes in F9 cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28683–28689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello D, Webber MM, Kleinman HK, Wartinger DD, Rhim JS. Androgen responsive adult human prostatic epithelial cell lines immortalized by human papillomavirus 18. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:1215–1223. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.6.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benecke A, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H. Synergy between estrogen receptor alpha activation functions AF1 and AF2 mediated by transcription intermediary factor TIF2. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:151–157. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettoun DJ, Burris TP, Houck KA, Buck DW, Stayrook KR, Khalifa B, Lu J, Chin WW, Nagpal S. Retinoid X Receptor is a Non-Silent Major Contributor to Vitamin D Receptor-Mediated Transcriptional Activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:2320–2328. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brelivet Y, Kammerer S, Rochel N, Poch O, Moras D. Signature of the oligomeric behaviour of nuclear receptors at the sequence and structural level. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:423–429. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruck N, Bastien J, Bour G, Tarrade A, Plassat JL, Bauer A, Adam-Stitah S, Rochette-Egly C. Phosphorylation of the retinoid x receptor at the omega loop, modulates the expression of retinoic-acid-target genes with a promoter context specificity. Cell Signal. 2005;17:1229–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TC, Wang L, Whitlatch LW, Flanagan JN, Holick MF. Prostatic 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1alpha-hydroxylase and its implication in prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:315–322. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Zhao Y, Hance KW, Shao A, Wood RJ, Fleet JC. Effects of MAPK signaling on 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-mediated CYP24 gene expression in the enterocyte-like cell line, Caco-2. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:132–142. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi PP, Hii CS, Ferrante A, Tan J, Der CJ, Omdahl JL, Morris HA, May BK. Role of MAP kinases in the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced transactivation of the rat cytochrome P450C24 (CYP24) promoter. Specific functions for ERK1/ERK2 and ERK5. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29643–29653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleet JC. Molecular actions of vitamin D contributing to cancer prevention. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleet JC, Wood RJ. Specific 1,25(OH)2 D3-mediated regulation of transcellular calcium transport in Caco-2 cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G958–G964. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.4.G958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman BM, Umesono K, Chen J, Evans RM. Unique response pathways are established by allosteric interactions among nuclear hormone receptors. Cell. 1995;81:541–550. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioeli D, Mandell JW, Petroni GR, Frierson HF, Jr, Weber MJ. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase associated with prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 1999;59:279–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Rimm EB, Hollis BW, Fuchs CS, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Prospective study of predictors of vitamin D status and cancer incidence and mortality in men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:451–459. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund TE, Moffatt KA, Miller GJ. Vitamin D receptor expression is required for growth modulation by 1 alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in the human prostatic carcinoma cell line ALAV-31. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;58:277–288. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(96)00030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hittelman AB, Burakov D, Iniguez-Lluhi JA, Freedman LP, Garabedian MJ. Differential regulation of glucocorticoid receptor transcriptional activation via AF-1-associated proteins. EMBO J. 1999;18:5380–5388. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerry DM, Dwivedi PP, Hahn CN, Morris HA, Omdahl JL, May BK. Transcriptional synergism between vitamin D-responsive elements in the rat 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 24-hydroxylase (CYP24) promoter. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29715–29721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko PL, Zhang Z, Cui M, Clinton SK, Fleet JC. 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D-mediated orchestration of anticancer, transcript-level effects in the immortalized, non-transformed prostate epithelial cell line, RWPE1. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Thompson EB. Transactivation functions of the N-terminal domains of nuclear hormone receptors: protein folding and coactivator interactions. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1–10. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Suh YA, Robinson MJ, Clifford JL, Hong WK, Woodgett JR, Cobb MH, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kurie JM. Stress pathway activation induces phosphorylation of retinoid X receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32193–32199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macoritto M, Nguyen-Yamamoto L, Huang DC, Samuel S, Yang XF, Wang TT, White JH, Kremer R. Phosphorylation of the human retinoid X receptor alpha at serine 260 impairs coactivator(s) recruitment and induces hormone resistance to multiple ligands. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4943–4956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707517200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann KK, Padovani AM, Guo Q, Colosimo AL, Lee HY, Kurie JM, Miller WH., Jr Arsenic trioxide inhibits nuclear receptor function via SEK1/JNK-mediated RXRalpha phosphorylation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2924–2933. doi: 10.1172/JCI23628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima-Nishiwaki R, Okuno M, Adachi S, Sano T, Akita K, Moriwaki H, Friedman SL, Kojima S. Phosphorylation of retinoid X receptor alpha at serine 260 impairs its metabolism and function in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7675–7682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInerney EM, Rose DW, Flynn SE, Westin S, Mullen TM, Krones A, Inostroza J, Torchia J, Nolte RT, Assa-Munt N, Milburn MV, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Determinants of coactivator LXXLL motif specificity in nuclear receptor transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3357–3368. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GJ, Stapleton GE, Hedlund TE, Moffat KA. Vitamin D receptor expression, 24-hydroxylase activity, and inhibition of growth by 1 alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in seven human prostatic carcinoma cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:997–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan R, Tovar SV, Falzon M, Weigel NL. The functional consequences of cross talk between the vitamin D receptor and ERK signaling pathways are cell specific. J Biol Chem. 2004;278:47298–47310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike JW, Zella LA, Meyer MB, Fretz JA, Kim S. Molecular actions of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on genes involved in calcium homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(Suppl 2):V16–V19. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.07s207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prufer K, Schroder C, Hegyi K, Barsony J. Degradation of RXRs influences sensitivity of rat osteosarcoma cells to the antiproliferative effects of calcitriol. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:961–976. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.5.0821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhim JS, Webber MM, Bello D, Lee MS, Arnstein P, Chen LS, Jay G. Stepwise immortalization and transformation of adult human prostate epithelial cells by a combination of HPV-18 and v-Ki-ras. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11874–11878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins DJ, Zhen EH, Cheng MG, Xu SC, Vanderbilt CA, Ebert D, Garcia C, Dang A, Cobb MH. Regulation and Properties of Extracellular Signal-Regulated Protein Kinase-1, Kinase-2, and Kinase-3. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1993;4:1104–1110. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V451104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roovers K, Assoian RK. Integrating the MAP kinase signal into the G1 phase cell cycle machinery. Bioessays. 2000;22:818–826. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200009)22:9<818::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebag M, Henderson J, Rhim J, Kremer R. Relative resistance to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in a keratinocyte model of tumor progression. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12162–12167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields JM, Pruitt K, McFall A, Shaub A, Der CJ. Understanding Ras: ‘it ain’t over ‘til it’s over’. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simboli-Campbell M, Narvaez CJ, Tenniswood M, Welsh J. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces morphological and biochemical markers of apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;58:367–376. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(96)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon C, White JH, Kremer R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibits 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3- dependent signal transduction by phosphorylating human retinoid X receptor alpha. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1729–1735. doi: 10.1172/JCI6871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Fleet JC. Intestinal Resistance to 1,25 Dihydroxyvitamin D in Mice Heterozygous for the Vitamin D Receptor Knockout Allele. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1396–1402. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola MV, Fromowitz F, Oravez S, Deb S, Finkel G, Lundy J, Hand P, Thor A, Schlom J. Expression of ras oncogene p21 in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:133–137. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198601163140301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajchmann HJ, Rathod B, Song S, Xu H, Wang X, Uskokovic MR, Studzinski GP. Loss of deoxcytidine kinase expression and tetraploidization of HL60 cells following long-term culture in 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Exp Cell Res. 1996;224:312–322. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang SH, Schwartz GG, Cameron D, Burnstein KL. Vitamin D receptor content and transcriptional activity do not fully predict antiproliferative effects of vitamin D in human prostate cancer cell lines. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997;126:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(96)03974-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman TL, Thevananther S, Ghose R, Burns AR, Karpen SJ. Nuclear export of retinoid X receptor alpha in response to interleukin-1beta-mediated cell signaling: roles for JNK and SER260. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15434–15440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]