Abstract

Motivation: We have implemented a coalescent simulation program for a structured population with selection at a single diploid locus. The program includes the functionality of the simulator ms to model population structure and demography, but adds a model for deme- and time-dependent selection using forward simulations. The program can be used, e.g. to study hard and soft selective sweeps in structured populations or the genetic footprint of local adaptation. The implementation is designed to be easily extendable and widely deployable. The interface and output format are compatible with ms. Performance is comparable even with selection included.

Availability: The program is freely available from http://www.mabs.at/ewing/msms/ along with manuals and examples. The source is freely available under a GPL type license.

Contact: gregory.ewing@univie.ac.at

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Coalescent simulations are a standard method to generate population samples under various models of evolution. The widely used simulator ms (Hudson, 2002) is a powerful tool for genealogies in general structured populations under neutrality, with high performance and an easy to use interface. However, it does not allow for selection. On the other hand, several programs are available to simulate polymorphism data for a neutral locus linked to a selected site (e.g. Kim and Stephan, 2002; Pennings and Hermisson, 2006b; Spencer and Coop, 2004; Teshima and Innan, 2009), but they do not allow for population structure. Only the specific scenario of selection in a colony population that has split from a large founder population without subsequent migration has been considered (Li and Stephan, 2006; Thornton and Jensen, 2006).

In msms, we implement the functionality of Hudson's ms in a simulator that allows for selection at a single diploid locus with two alleles. For neutral genealogies, the program's usage and assumptions are identical to ms. In particular, msms is compatible with ms in both output format and command-line options. This permits the wide range of tools that work with ms to also work with msms. Complicated models can now have selection added with only small adjustments and by swapping ms with msms. Applications include the power of various tests to detect selective sweeps in structured populations, including adaptation from standing genetic variation and from recurrent mutation (soft sweeps, Hermisson and Pennings, 2005; Pennings and Hermisson, 2006a, b), the genetic footprint of local adaptation and adaptive gene flow after population splits. Extensions beyond previous programs also include the output of joint site-frequency spectra and the possibility of specifying multiple neutral loci. The performance of msms is generally comparable to ms (see the manual for a detailed runtime comparison). Complex population demographies can therefore be studied with selection added, without imposing additional computation time limitations. The name msms refers to the German ‘ “mach” Stichprobe mit Selektion’ (i.e. make sample with selection).

2 METHODS

The coalescent (Hudson, 1983; Kingman, 1982) is a stochastic process to generate genealogies from a population by tracing randomly sampled alleles backwards in time. Population structure, as well as demography and recombination, are readily incorporated into a coalescent framework (for review, Hein et al., 2005; Wakeley, 2008).

To include selection into a simulator based on the coalescent, we extend the approach of (Kaplan et al., 1989) and (Barton et al., 2004) to the case of structured populations. Conditioned on the frequency paths of the beneficial allele in all demes of the metapopulation, ancestral lines of one or several neutral markers linked to the beneficial allele can be followed backward in time. The structured coalescent as described by (Kaplan et al., 1989) is thus structured by both geography and genetic background. It is implemented by a three-step procedure. (i) The first step consists of generating the frequency paths (trajectories) of the selected allele in all demes by multinomial sampling in a Wright–Fisher model for an arbitrary geographical structure. (ii) The second step is the construction of the genealogy at one or several neutral loci using a structured ancestral recombination graph conditioned on the frequency paths. (iii) Finally, neutral mutations are added to the branches of the genealogical tree according to a Poisson process.

Forward simulations: in the current version of the program, the time-forward simulations to generate the trajectory of the selected allele assume selection at a single locus with two alleles A and a. Individuals can be haploid or diploid. For diploids, the fitness values for the three genotypes in deme i are 1+saai, 1+saAi and 1+sAAi, respectively. Selection can differ among demes. Migration from deme j to deme i is defined as the proportion mij of deme i that is made up of migrants from deme j. We let mii = 1−∑j mij, which is the proportion of non-migrants in deme i. Let Ni and ni be the population size and the number of A copies in deme i, respectively, and xi = ni/(2Ni) its frequency. The simulator allows for recurrent mutation at the selected site with rates μ from a → A and ν from A → a. All model parameters (for mutation, selection and migration) can change with time in a step-wise fashion. The simulator further allows for changes in population size and in the number of demes (splits and mergers) in analogy to ms.

Consider a single deme i with proportion xi of the A allele. Selection, mutation and migration occur according to the deterministic recurrence equation

| (1) |

where

| (2) |

| (3) |

Drift is included by binomial sampling of the infinite population. The number ni′ of A copies in the next generation is given by

| (4) |

Simulation runs start with an arbitrary starting frequency x(0) and continue until some stopping condition (e.g. loss or fixation of the A allele) is met.

Coalescent simulations: simulations with recombination according to the ancestral recombination graph (ARG) are carried out conditional on the frequency of the A allele in all demes. In the time before the first origin of A, and after its fixation in all demes (if applicable), the ARG is the standard neutral one (in a structured population). During the selection phase, events of different types (coalescence, mutation at the selected locus, migration and recombination) occur according to a competing Poisson process scheme with rates that depend on the stochastic trajectory of the selected allele. For example, coalescence in the A and a background in deme i occurs at rates proportional to 1/xi(t) and 1/(1−xi(t)), respectively, and migration of the selected allele from j to i (forward in time) at a rate proportional to xj(t)/xi(t). Rates for other events and all details are given in the documentation (Supplementary Material).

The coalescent simulations assume continuous time and events are not linked to discrete generation steps. For high recombination and migration rates, and for low frequencies of the A allele, the time between consecutive events can get smaller than a generation time. To reconcile this with the discrete time-forward simulations, the trajectory of the A allele is treated as a piecewise constant function with (potential) jumps after every generation.

Validation: the simulation program was validated using ms for complex neutral genealogies and for selection in a panmictic population using the simulator by (Pennings and Hermisson, 2006a), which builds on (Kim and Stephan, 2002). No significant deviations were found when comparing marginal allele frequency spectra or the distribution of Tajima's D statistic with a χ2 or Kolmogrorov–Smirnov test. Appropriate analytical results have also been checked and matched.

3 EXAMPLE

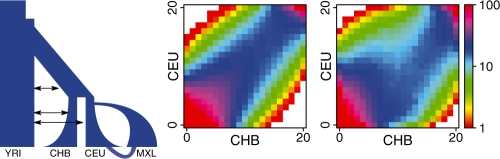

To illustrate the capabilities of the program and its performance, we use the model for human demography with parameters inferred in (Gutenkunst et al., 2009). Example parameters and the program command line for this example are included in the manual. Figure 1 shows pairwise spectra for Europeans and Asians under neutrality and with selection only in the European population. The initial frequency of the beneficial allele is zero, adaptation occurs from recurrent mutation at the selected locus. The run times for 10 000 replicates were 142 s and 156 s for the neutral and the selected case, respectively (using a single core of a 2.2 GHz quad core AMD Opteron processor). Thus, considering selection does not adversely degrade running times permitting a wide range of applications.

Fig. 1.

Demographic model and pairwise joint frequency spectra. The model includes four populations (YRI, CHB, CEU and MXL for African, Asian, European and Mexican, respectively), splits, admixture, migration, growth and bottlenecks. The left and right spectra show the neutral and a selected case, respectively. The scale is counts for each bin.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Peter Pfaffelhuber, Cornelia Borck, Ines Hellmann, Pleuni Pennings and Pavlos Pavlidis for discussions and β-testing the program, and Jayne Ewing for support and proof reading. We thank CIBIV for the use of the computer cluster and other infrastructure support.

Funding: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG); the Vienna Science and Technology Fund (WWTF).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Barton NH, et al. Coalescence in a random background. Ann. Appl. Probab. 2004;14:754–785. [Google Scholar]

- Gutenkunst RN, et al. Inferring the joint demographic history of multiple populations from multidimensional SNP frequency data. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein J, et al. Gene Genealogies, Variation and Evolution: A Primer in Coalescent Theory. 1. New York, USA: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hermisson J, Pennings PS. Soft sweeps: molecular population genetics of adaptation from standing genetic variation. Genetics. 2005;169:2335–2352. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.036947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR. Properties of a neutral allele model with intragenic recombination. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1983;23:183–201. doi: 10.1016/0040-5809(83)90013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR. Generating samples under a Wright-Fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:337–338. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan NL, et al. The “Hitchhiking Effect” revisited. Genetics. 1989;123:887–899. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.4.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Stephan W. Detecting a local signature of genetic hitchhiking along a recombining chromosome. Genetics. 2002;160:765–777. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.2.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingman J.FC. The coalescent. Stochas. Process. Appl. 1982;13:235–248. [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Stephan W. Inferring the demographic history and rate of adaptive substitution in drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennings PS, Hermisson J. Soft sweeps III: the signature of positive selection from recurrent mutation. PLoS Genet. 2006a;2:e186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennings PS, Hermisson J. Soft sweeps II - molecular population genetics of adaptation from recurrent mutation or migration. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006b;23:1076–1084. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer C.CA, Coop G. SelSim: a program to simulate population genetic data with natural selection and recombination. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3673–3675. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teshima K, Innan H. mbs: modifying hudson's ms software to generate samples of DNA sequences with a biallelic site under selection. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton KR, Jensen JD. Controlling the false positive rate in multilocus genome scans for selection. Genetics. 2006;175:737–750. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.064642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeley J. Coalescent Theory: An Introduction. 1. Greenwood Village, Colorado, USA: Roberts & Company Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.