Synopsis

Portal hypertensive gastropathy and gastric antral vascular ectasia may cause gastrointestinal hemorrhage in patients with portal hypertension. While the former presents exclusively in patients with portal hypertension; gastric antral vascular ectasia can also be observed in patients with other conditions. Diagnosis is established with upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, although some cases may require a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. The most frequent manifestation is ferropenic anemia that may become transfusion dependent. Treatment in portal hypertensive gastropathy is focused on portal pressure reducing drugs, mainly non selective beta-blockers while in gastric antral vascular ectasia it is based on endoscopic ablation. More invasive options can be utilized in case of failure of first line therapies, although this should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Keywords: portal hypertensive gastropathy, gastric antral vascular ectasia, portal hypertension, cirrhosis, management

Patients with cirrhosis are at an increased risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage, with the most common source being gastroesophageal varices. However, there are gastrointestinal mucosal lesions typical of cirrhosis that may also bleed in these patients, namely portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) and gastric vascular ectasia (GAVE). These are two clearly distinct mucosal lesions with different pathophysiology, endoscopic appearance, histopathology and treatment (Table 1). PHG, as its name indicates, is associated with the presence of portal hypertension and therefore is only observed in patients with this condition, while GAVE is observed in patients without portal hypertension or liver disease. Nevertheless and despite the differences between both entities, they may lead to similar clinical manifestations, most frequently to symptoms due to chronic ferropenic anemia associated to chronic occult blood loss and only rarely lead to acute, overt gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Table 1.

Differential characteristics between Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy and Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia

| Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy |

Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia |

|

|---|---|---|

| Causal |

Relationship with portal

hypertension |

Coincidental |

| Mainly proximal | Distribution in stomach | Mainly distal |

| + |

Presence in other

territories of GI tract |

- |

| Mosaic pattern + red spots |

Endoscopic findings | Linear pattern + red spots |

| Severe portal hypertensive gastropathy |

Difficult differential

diagnosis |

Diffuse gastric vascular ectasia |

| Dilated capillaries and venules No inflamation |

Pathology | Thrombi Spindle cell proliferation Fibrohyalinosis |

| Portal pressure reducing | Treatment | Endoscopic |

| TIPS/Shunt surgery | Salvage therapy * | Antrectomy and Billroth I |

to be evaluated on an individual basis

SMT: somatostatin; TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic shunt

Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy

Portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) is characterized by more or less typical gastric mucosal lesions presenting in patients with portal hypertension (either pre-hepatic or hepatic). Its typical location is in the gastric fundus and upper body of the stomach although it can affect the whole stomach and even other areas of the gastrointestinal tract, such as the small bowel or the colon 1-8.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of PHG in patients with portal hypertension has been reported to vary between 20% and 80% 1, 9-12. The wide variation in the reported prevalence is most likely due to differences in the study population specifically, the proportion of patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, the severity of the underlying liver disease, and the proportion of patients with previous endoscopic treatment. A higher rate of PHG is observed in patients with more severe liver disease 10, 11 and in patients who have had previous endoscopic treatment with sclerotherapy or endoscopic variceal ligation 1, 9, 12 There is controversy regarding the specific endoscopic technique used for variceal eradication that leads to a higher prevalence of PHG, with some studies showing a higher incidence after sclerotherapy than after ligation and other studies showing a similar incidence with both techniques 13-15. Although many studies have concluded that the presence of PHG is associated with indirect signs of portal hypertension such as the presence of larger varices 1, 11, splenomegaly 10, 11 and low platelet count 11, the studies that evaluated the association between the hepatic venous pressure gradient, a well established method to measure portal pressure 16, and PHG have lead to controversial results. Two studies found no clear relationship between HVPG and PHG 17, 18, while another study found that patients with more severe gastropathy had a higher HVPG than patients with mild or no gastropathy19. These controversial results may be due to selection bias, as all patients who were included in these studies had clinically significant portal hypertension 17, 18. The issue would be clearer if it could be demonstrated that PHG presents only in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension (HVPG ≥ 6mmHg) or only in those with clinically significant portal hypertension (HVPG ≥ 10mmHg). However, such studies are still lacking.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of PHG is unclear although portal hypertension plays a major role. Studies that have evaluated the prevalence PHG have revealed that it is almost exclusively observed in patients with portal hypertension, with or without liver disease 20, 21. PHG was not observed in 100 patients with chronic alcoholism without signs of liver disease or portal hypertension (on ultrasonographic examination) or in 10 patients with cirrhosis without portal hypertension 21. It is not a peptic process, as mucosal changes do not respond to antisecretory drugs and histological changes, predominantly dilated capillaries and venules in the mucosa and submucosa without significant inflammation, are clearly distinct from those typically observed in peptic related disease 22. Nevertheless, it seems that the gastric mucosa has an increased susceptibility to injury by noxious factors, as well as impaired healing 23-26.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PHG, and by extension portal hypertensive enteropathy (similar mucosal changes at other sites of the gastrointestinal tract) is established when the characteristic endoscopic findings are observed in patients with portal hypertension. PHG is classified as mild when only the snake-skin mosaic pattern is present or severe when, in addition to the mosaic pattern, flat or bulging red marks or black-brown spots are observed 27. The clinical relevance of this classification has been established since patients with severe PHG are more likely to have acute bleeding or chronic anemia than patients with mild PHG 11, 28. Furthermore, this classification is reproducible as a fairly good concordance between observers has been shown, especially regarding the mosaic pattern and red marks 28. Similar lesions as the ones observed in the stomach in patients with PHG have been observed in the small bowel 3, 5, 7, 29, 30 and the colon 2, 7.

Some studies have evaluated alternative non-endoscopic methods for the diagnosis of PHG 31, 32 such as MRI or CT although until further evaluation in larger populations is available, endoscopy still remains the chief diagnostic method. In a study evaluating the efficacy of capsule endoscopy in the evaluation of the presence and size of varices, capsule endoscopy was shown to have only moderate sensitivity and specificity for the detection of PHG 33. Future studies should specifically evaluate its efficacy in evaluating not only the presence but also the severity of PHG as capsule endoscopy will be particularly important in the evaluation of lesions in the small bowel.

Natural history

PHG may change with time in an individual patient. Studies that have evaluated the natural history of PHG have described controversial results, possibly due to differences in study population. If only patients with cirrhosis who do not require primary or secondary prophylaxis are included, approximately 30% of patients with mild PHG develop severe PHG during a follow up period ranging from 12 to 103 months11. Only a few cases of improvement in PHG are described. Most of the cases that bleed from PHG occur in patients with de novo PHG or in those with worsening of previous PHG 9, 11. Patients with diffuse lesions are more likely to bleed 9, 12. Patients who have PHG associated to cirrhosis-related portal hypertension have more frequently persistent and progressive PHG (which is more likely to bleed) than patients with PHG related to non-cirrhotic portal hypertension 9. Although, as mentioned above, patients with previous endoscopic therapy (sclerotherapy or endoscopic variceal ligation) have a higher prevalence of PHG 1, 9, 12, the clinical course of the PHG in this context, particularly in non cirrhotic portal hypertension, may be milder and transient 9, 14. Studies that have focused on patients with cirrhosis have not observed differences in severity or course of PHG in patients who develop it spontaneously or after endoscopic therapy 1.

Clinical picture

PHG is mostly asymptomatic but, when symptomatic, it most frequently causes chronic gastrointestinal blood loss and ferropenic anemia. No study has evaluated the prevalence of PHG in cirrhotic patients with chronic anemia. The rate of chronic hemorrhage in patients with PHG ranges between 6-60% in different studies 1, 9, 11, 34. This wide variation is due to a great heterogeneity in the patient population included in the different studies, from patients without cirrhosis 9 to patients with cirrhosis and severe PHG 34. Chronic bleeding from PHG is suspected in a patient with portal hypertension and chronic ferropenic anemia and its presence is confirmed upon thorough examination of the whole gastrointestinal tract including upper endoscopy, colonoscopy and evaluation of the small bowel which is most easily done with capsule endoscopy.

Although PHG may bleed acutely leading to hematemesis and/or melena, this accounts for only a minority of cases of acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. In a study that included 250 patients with cirrhosis presenting with GI hemorrhage in whom a source could be identified, PHG accounted for only 5% of the cases, with varices (57%) and peptic disease (17%) being the most frequent sources 35. Studies that evaluate the probability of bleeding from PHG report an incidence between 2.5-30% 1, 9, 11, 34, with the greatest incidence observed in patients with severe PHG 9, 11, 34. Diagnosis of acute hemorrhage from PHG is established when active bleeding from gastropathy lesions or non-removable clots overlying these lesions is observed or when there is PHG and no other cause of acute bleeding can be demonstrated after thorough evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract.

Management

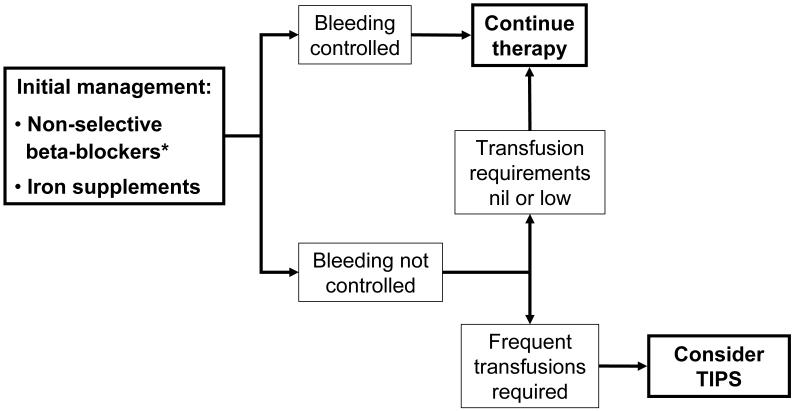

Treatment of PHG relies on two main pillars. Firstly, general measures used in gastrointestinal bleeding independent of cause should be applied and secondly a specific approach to treat the cause of the gastrointestinal bleed should be undertaken. The most effective specific treatments in patients with PHG are those aimed at reducing portal pressure. The main pharmacological agent that has been investigated in this setting is the nonselective beta-blocker propranolol.

a) Chronic hemorrhage

In the most frequent context of chronic blood loss, iron supplementation should be provided in order to counteract the continuous depletion of iron deposits. The most effective specific therapy is that aimed at reducing portal pressure. Non-selective beta-blockers have been shown to decrease bleeding from both acute and chronic forms of hemorrhage from PHG. The first trial 36 was a randomized controlled trial that included only 24 patients. Patients with portal hypertension evidenced by the presence of varices and PHG diagnosed at least 6 weeks before inclusion were randomized to the administration of long acting propranolol (160 mg/day) or placebo initially for 6 weeks and then crossed-over to the other arm for another 6 weeks. While patients were on propranolol, there was a lower rate of hemorrhage, an increase in hemoglobin level and an apparent improvement in the endoscopic appearance of the lesions, compared to the placebo period. However, the study was underpowered to yield any significant statistical or clinical conclusions.

More solid evidence supporting the use of propranolol in the prevention of recurrent bleeding in patients with cirrhosis and severe PHG was obtained from a randomized controlled trial in which patients who had previously bled acutely or chronically from PHG were randomized to receive propranolol (26 patients) or no therapy other than iron administration if needed (28 patients) 34. The end-point of the trial was recurrent hemorrhage from PHG. This was defined as a) the presence of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding with a decrease in hematocrit and the finding on emergency endoscopy (performed within the first 12 hours) of gastric red spots as the source of bleeding, or b) the presence of chronic bleeding defined by occult blood loss with transfusion requirements of 3 or more units of red packed blood cells in 3 months or continuous iron repacement therapy for more than 50% of the time of follow-up. The actuarial probability of remaining free of hemorrhage was greater in patients randomized to propranolol both in the acute (85% vs. 20%) and in the chronic setting (63% vs. 40% at 30 months), although in the latter this difference did not achieve statistical significance 34. On multivariate analysis, the only independent predictor of recurrent hemorrhage was the absence of propranolol 34. Therefore, non-selective beta-blockers should be used both in the chronic setting and in the acute setting (once the acute episode is controlled). Propranolol is given at an initial dose of 20 mg BID, gradually escalated to 160 mg BID or the maximum tolerated dose according to heart rate (50-55 bpm) or secondary effects (light-headedness, asthenia, etc). This therapy should be maintained as long as the patient continues to have portal hypertension.

Use of other pharmacologic agents in PHG such as losartan 37, thalidomide 38 and corticosteroids39 has been described. However the evidence supporting the use of these agents is weak with small open-label studies and case reports.

Non-response to beta-blockers should be considered when the patient continues to bleed and is transfusion-dependent despite betablockers and iron replacement therapy. Patients who only require occasional transfusions will not benefit from more invasive therapeutic options, although this should be evaluated on an individual basis.

Since portal hypertension is the main underlying factor that leads to the development of PHG, shunt therapies have been evaluated as salvage therapies. Data has been reported regarding the use of both the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) 40-43 and shunt surgery 44, 45. TIPS placement consists in the creation of a shunt between a hepatic vein and a portal vein. From a hemodynamic point of view it is similar to a side to side surgical portacaval shunt and is very effective in lowering portal pressure. Almost all patients who receive TIPS demonstrate an improvement of PHG lesions on endoscopic evaluation and a decrease in transfusion requirements 40-43. In the largest study (40 patients with PHG) endoscopic improvement was detected as early as 6 weeks after TIPS placement, although in patients with severe PHG it could take at least 3 months 40. Similar results have been shown with shunt surgery, that is, improvement in endoscopic appearance and lower transfusion requirements 44, 45. Due to the morbidity associated with shunt surgery, particularly in patients with cirrhosis, its role may be more relevant in patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension 45.

Only one study has evaluated the use of endoscopic treatment of PHG with argon plasma coagulation (APC)46. This study included 29 patients, of which 11 were considered to be bleeding from PHG, defined as diffuse vascular ectasia with a background mosaic pattern distributed throughout the stomach in patients with portal hypertension. The APC was set at 30 to 40 W and 1.5 to 2 l/min of argon plasma flow. The aim of each session was to ablate as much of the surface as possible, at least 80% of the mucosa in diffuse lesions. Sessions were repeated as needed every 2 to 4 weeks. The treatment success, defined by the absence of further episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding or a reduction in blood transfusion requirements, was between 81 and 90% without any significant differences between groups. The data is limited and this endoscopic approach could be considered in patients in whom severe recurrent bleeding occurs despite beta-blockers and who are not candidates for TIPS.

b) Acute hemorrhage

Although PHG may present as acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage, this presentation is less frequent than chronic blood loss. As in all patients with acute hemorrhage, general measures should be undertaken. Adequate volume resuscitation should be provided. Even though data specific for acute hemorrhage from PHG is not available given its low frequency, it would appear reasonable to apply general measures proven to be efficacious in improving outcomes in patients with acute variceal hemorrhage such as cautious blood transfusion aimed at maintaining a hemogobin of around 8 g/dL and the use of prophylactic antibiotics 47. Oral or intravenous quinolones are the recommended antibiotics such as norfloxacin (400 mg BID) or ciprofloxacin (500 mg BID PO, 200 mg BID IV). Intravenous ceftriaxone (1 g/day) may be preferred in patients with Child B or C cirrhosis, or in those undergoing prophylaxis with quinolones48.

Besides the general measures, a specific portal hypotensive approach should be undertaken. The use of betablockers in the acute setting was evaluated in an open trial in acute severe bleeding from endoscopically-proven PHG (14 patients) 36. In this context, all but one patient ceased to bleed within 3 days of the initiation of propranolol 36. However, the gradual dose titration of the drug necessary to achieve adequate beta-blockade is not ideal in this setting, particularly when blunting the physiologic compensatory increase in heart rate that results from acute bleeding would appear counterintuitive. In this setting, vasoactive drugs used routinely in the setting of variceal hemorrhage such as somatostatin and its analogues (octreotide and vapreotide) and vasopressin and its analogue, terlipressin, which are effective by means of producing a decrease in portal pressure 49, 50, could be useful from a theoretical point of view. In fact, three trials have evaluated the use of these drugs in acute hemorrhage from PHG 51-53. Hemorrhage was satisfactorily controlled with somatostatin 53, octreotide 52, 53 or terlipressin 51 although vasopressin 52 did not show any benefit in comparison to omeprazole. Furthermore, in the trial that evaluated the effect of terlipressin, patients who received a larger (1 mg/4 hours) dose of terlipressin had a higher proportion of control of hemorrhage and a lower recurrence rate than those who received a lower dose (0.2mg/4 hours) 51.

Therefore, following current recommendations 47, resuscitation, a safe vasoactive drug (somatostatin or terlipressin) and antibiotic prophylaxis should be started as soon as gastrointestinal bleeding is suspected in a patient with cirrhosis, preferably before upper endoscopy. It seems reasonable that once the diagnosis of bleeding due to PHG is established, these drugs should be maintained.

In cases of acute hemorrhage that does not respond to medical treatment, alternative approaches should be contemplated. Non response to medical treatment in the acute setting may be defined according to the standards of non response to variceal bleeding 27, as both are associated to portal hypertension and require a change of therapy. Treatment failure is considered when there is a new hematemesis after at least 2 hours of treatment initiation, or a 3 gr drop in hemoglobin in the absence of transfusion of packed red blood cells or an inadequate hemoglobin increase in response to blood transfusions, or death 27.

Rescue therapies in patients in whom standard therapy fails are the same as those recommended in patients who fail standard therapy for chronic bleeding.

Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is characterized by the presence of red spots without a background mosaic pattern that are typically located in the gastric antrum. GAVE is most frequently observed in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, although they have also been observed in patients without cirrhosis such as autoinmune connective tissue disorders, bone marrow transplantation or chronic renal failure 54-57. Seemingly, patients with cirrhosis have more often diffuse disease 58 while in non-cirrhotic patients the disease is most frequently limited to the antrum 59, 60. In contrast to PHG, GAVE is only observed in the stomach and not in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract. The prevalence of GAVE in cirrhosis is very low. In a recent study performed in patients awaiting liver transplantation, GAVE was observed in only 8/345 (2%) of the patients 61. A similar prevalence has been described in patients with HCV and advanced fibrosis 10.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of GAVE is not fully understood. In patients with cirrhosis, portal hypertension appears not to be essential in its development as patients do not respond to portal pressure-reducing therapies, such as TIPS or surgical shunt 40, 62. Liver insufficiency seems to play a significant role in the development of GAVE because it develops in patients with more severe liver dysfunction 59 and it has been shown to resolve after liver transplantation 61, 63. Speculation regarding an accumulation of substances not metabolized by the liver which may induce vasodilatation and/or angiogenesis has been suggested as a posible mechanism 62. The association between GAVE and hormones with vasodilating properties such as gastrin 18, 54, 59 and prostaglandin E264 has also been suggested. Finally abnormal antral motility 65 and mechanical stress 18 have also been associated to the pathogenesis of GAVE which is further supported by the antral distribution of the lesions.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of GAVE is established when the characteristic red spots (without a background mosaic pattern) are seen in the stomach at endoscopy. These lesions are typically found in the antrum, and in occasions are aggregated in a linear distribution, so that one may observe red longitudinal stripes which may be flat or raised, with visible blood vessels and pale normal mucosa in between, similar to a watermelon, for which the term “watermelon-stomach” is used 54. In occasions, the lesions are distributed diffusely throughout the proximal and distal stomach. In these cases the term “diffuse gastric vascular ectasia” is preferred 54. The appearance of diffuse GAVE may be very similar to severe PHG and it is important to differentiate them as treatment will be different 66.

Histologically, GAVE lesions are completely distinct from PHG so biopsy can be used to distinguish between these two entities particularly in those cases in which the endoscopic appearance of the lesions may lead to some confusion 59. Findings in full-thickness mucosal biopsies that are highly suggestive of GAVE are mucosal vascular ectasia, fibrin thombi, fibrohyalinosis and spindle cell proliferation without signs of inflammation. However, the absence of these characteristics on biopsy does not preclude its diagnosis as biopsies are normally not deep enough 67.

Clinical presentation

From a clinical perspective, GAVE presents in a similar manner as PHG, that is, while most patients are completely asymptomatic, others present with acute or chronic hemorrhage and iron deficiency anemia. Acute hemorrhage appears to be more frequent in patients with cirrhosis, while non-cirrhotic patients will generally present with anemia 60. In a study in which patients (with or without cirrhosis) underwent endoscopic evaluation of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, GAVE was the cause of hemorrhage in 26/744 patients (4%). Approximately a third of these patients with GAVE had underlying portal hypertension 58.

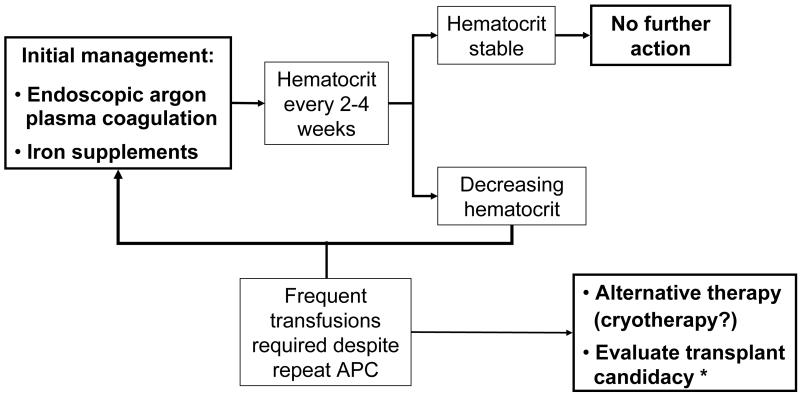

Management

In the setting of acute hemorrhage, the general therapeutic measures recommended for patients with cirrhosis and acute hemorrhage from varices or PHG (see above) will apply to patients with cirrhosis who bleed acutely from GAVE.

Specific measures to treat patients with GAVE with acute or chronic bleeding are substantially different from those used in PHG. The mainstay of therapy in GAVE is the endoscopic ablation of the lesions. Some other studies have evaluated the use of different drugs and other more invasive options, but these should be used once an endoscopic therapy has failed.

Many different endoscopic approaches have been used in the setting of GAVE although most studies have evaluated the use of thermoablative techniques. Typically several sessions are needed to achieve a control of acute bleeding and to correct anemia due to chronic blood loss.

The use of neodymium:yttrium-aluminium-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser coagulation has shown to be effective in reducing rebleeding and transfusion requirements 54, 56, 68-71. Its main advantage is that it can be applied to a fairly large suface area of the mucosa in a single session and that its hemostatic response may be observed earlier. On the other hand the risk of perforation is greater than with other thermablative approaches such as argon plasma coagulation as the thermal effect penetrates deeper. The Nd:YAG laser is placed 1 cm from mucosa surface and is used with a power setting between 40-90 W with short pulse durations (0.5-1 sec). Sessions should be repeated every 2-4 weeks until the therapeutic goal is achieved.

The most numerous studies evaluating the use of thermoablative methods in the treatment of GAVE are with argon-plasma coagulation which produces thermal coagulation by applying high frequency electric current that is passed through with argon gas without direct contact with the mucosa. Several studies have demonstrated the beneficial effect of this method in patients with GAVE 46, 58, 60, 72-78. The main advantage of argon-plasma coagulation is that it is easy to use and the risk of perforation is lower than with Nd:YAG laser. Large areas of mucosa may be treated in a single session although this is very time consuming. Complications associated to this method are the development of hyperplasic polyps 78-80 and gastric outlet obstruction 77, 81. The settings for the electrical power (20 to 80W) and gas flow (0.5-2 L/min) vary throughout the studies. The technique combines both focal pulse and “paint brush”. The sessions should be repeated every 2-6 weeks as needed.

Other endoscopic therapeutic options such as sclerotherapy and heater probe ablation 82 do not appear to have significant advantages over the previously described methods. However there are other endoscopic approaches with more limited experience that may offer some additional advantages. Cryotherapy 83, 84 consists of rapid expansion in the stomach of compressed nitrous oxide resulting in a local decrease of the temperature with consequent freezing of the mucosa. The cryospray is applied with a specific catheter until ice is formed. Endoscopy should be repeated until all lesions are fully treated. The main advantage of this approach is that it allows for a faster and more extensive treatment of diffuse lesions. Recently, the use of banding in the stomach antrum with the same system that is used for variceal ligation has been evaluated for the treatment of GAVE 85, 86. This method offers the advantage that a large area of mucosa can be treated at once and it is a technique that is easily accesible to many centers. In a controlled trial comparing banding to thermoablative treatment, patients who received banding had a significantly greater increase in hemoglobin, decrease in blood transfusion requirements and hospital admissions 85.

Limited experience has been reported regarding the use of different pharmacological treatments for GAVE. Pilot studies have suggested that the use of estrogen-progesterone may be useful, so that this could be tried if endoscopic treatment fails 87-89. Some success has been described in case reports with the use of octreotide90, corticosteroids 91, 92, tranexamic acid 93, thalidomide 94, and a serotonin antagonist 95. Some cases have resolved with treatment of the underlying disease such as liver transplantation in patients with cirrhosis 61, 63, although there has been a report of worsening GAVE despite adequate control of the underlying disease, systemic sclerosis and interstitial pneumonitis 96

In extreme cases in which the combination of endoscopic and pharmacological treatment is unsuccessful, surgery with antrectomy can be considered on an individual basis 97-99. The preferred procedure is antrectomy with Billroth I anastomosis. A thorough endoscopic evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract should be performed in order to exclude other causes of bleeding before turning to surgery. This is the most definitive therapy with low rates of rebleeding and anemia. However, morbidity and mortality are high, particularly in patients with decompensated cirrhosis in who GAVE usually presents.

Conclusion

PHG and GAVE are two different clinical entities that share a common clinical manifestation, gastrointestinal bleeding. Most cases will present as chronic bleeding, although there may be some cases of acute life threatening bleed. Besides the common clinical manifestation, these two entities are clearly distinct with different pathophysiology, endoscopic appearance and therapeutic approach. The treatment of PHG is based on measures that reduce portal pressure, namely the administration of betablockers. On the other hand, gastric vascular ectasia responds to endoscopic treatment. Most studies in this context have used thermoablative techniques, mainly argon-plasma coagulation. Refractory cases can respond to more invasive therapeutic options, although this has to be evaluated individually.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBERehd) and Yale Liver Center NIH P30 DK34989.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Cristina Ripoll, Hepatology and Liver Transplant Unit, Department of Digestive Diseases, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Madrid. Spain.

Guadalupe Garcia-Tsao, Section of Digestive Diseases, Yale University School of Medicine and VA-CT Healthcare System, New Haven, CT, U.S.A..

References

- (B)1.Primignani M, Carpinelli L, Preatoni P, et al. Natural history of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with liver cirrhosis. The New Italian Endoscopic Club for the study and treatment of esophageal varices (NIEC) Gastroenterology. 2000 Jul;119(1):181–187. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bresci G, Parisi G, Capria A. Clinical relevance of colonic lesions in cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension. Endoscopy. 2006 Aug;38(8):830–835. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Figueiredo P, Almeida N, Lerias C, et al. Effect of portal hypertension in the small bowel: an endoscopic approach. Dig Dis Sci. 2008 Aug;53(8):2144–2150. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0111-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (B)4.Goulas S, Triantafyllidou K, Karagiannis S, et al. Capsule endoscopy in the investigation of patients with portal hypertension and anemia. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008 May;22(5):469–474. doi: 10.1155/2008/534871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higaki N, Matsui H, Imaoka H, et al. Characteristic endoscopic features of portal hypertensive enteropathy. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(5):327–331. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito K, Shiraki K, Sakai T, Yoshimura H, Nakano T. Portal hypertensive colopathy in patients with liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005 May 28;11(20):3127–3130. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i20.3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menchen L, Ripoll C, Marin-Jimenez I, et al. Prevalence of portal hypertensive duodenopathy in cirrhosis: clinical and haemodynamic features. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Jun;18(6):649–653. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200606000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misra SP, Dwivedi M, Misra V. Prevalence and factors influencing hemorrhoids, anorectal varices, and colopathy in patients with portal hypertension. Endoscopy. 1996 May;28(4):340–345. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (B)9.Sarin SK, Shahi HM, Jain M, Jain AK, Issar SK, Murthy NS. The natural history of portal hypertensive gastropathy: influence of variceal eradication. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Oct;95(10):2888–2893. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (B)10.Fontana RJ, Sanyal AJ, Mehta S, et al. Portal hypertensive gastropathy in chronic hepatitis C patients with bridging fibrosis and compensated cirrhosis: results from the HALT-C trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006 May;101(5):983–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (B)11.Merli M, Nicolini G, Angeloni S, Gentili F, Attili AF, Riggio O. The natural history of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with liver cirrhosis and mild portal hypertension. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Oct;99(10):1959–1965. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (B)12.D’Amico G, Montalbano L, Traina M, et al. The Liver Study Group of V. Cervello Hospital Natural history of congestive gastropathy in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1990 Dec;99(6):1558–1564. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90458-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuksel O, Koklu S, Arhan M, et al. Effects of esophageal varice eradication on portal hypertensive gastropathy and fundal varices: a retrospective and comparative study. Dig Dis Sci. 2006 Jan;51(1):27–30. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hou MC, Lin HC, Chen CH, et al. Changes in portal hypertensive gastropathy after endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy or ligation: an endoscopic observation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995 Aug;42(2):139–144. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshikawa I, Murata I, Nakano S, Otsuki M. Effects of endoscopic variceal ligation on portal hypertensive gastropathy and gastric mucosal blood flow. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998 Jan;93(1):71–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.071_c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groszmann RJ, Wongcharatrawee S. The hepatic venous pressure gradient: anything worth doing should be done right. Hepatology. 2004;39(2):280–282. doi: 10.1002/hep.20062. 2004/02// [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellis L, Nicodemo S, Galossi A, et al. Hepatic venous pressure gradient does not correlate with the presence and the severity of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007 Sep;16(3):273–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quintero E, Pique JM, Bombi JA, et al. Gastric mucosal vascular ectasias causing bleeding in cirrhosis. A distinct entity associated with hypergastrinemia and low serum levels of pepsinogen I. Gastroenterology. 1987 Nov;93(5):1054–1061. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90569-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwao T, Toyonaga A, Sumino M, et al. Portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1992 Jun;102(6):2060–2065. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90332-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarin SK, Misra SP, Singal A, Thorat V, Broor SL. Evaluation of the incidence and significance of the “mosaic pattern” in patients with cirrhosis, noncirrhotic portal fibrosis, and extrahepatic obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988 Nov;83(11):1235–1239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papazian A, Braillon A, Dupas JL, Sevenet F, Capron JP. Portal hypertensive gastric mucosa: an endoscopic study. Gut. 1986 Oct;27(10):1199–1203. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.10.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCormack TT, Sims J, Eyre-Brook I, et al. Gastric lesions in portal hypertension: inflammatory gastritis or congestive gastropathy? Gut. 1985 Nov;26(11):1226–1232. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.11.1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawanaka H, Tomikawa M, Jones MK, et al. Defective mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK2) signaling in gastric mucosa of portal hypertensive rats: potential therapeutic implications. Hepatology. 2001 Nov;34(5):990–999. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinjo N, Kawanaka H, Akahoshi T, et al. Significance of ERK nitration in portal hypertensive gastropathy and its therapeutic implications. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008 Nov;295(5):G1016–1024. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90329.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarfeh IJ, Soliman H, Waxman K, et al. Impaired oxygenation of gastric mucosa in portal hypertension. The basis for increased susceptibility to injury. Dig Dis Sci. 1989 Feb;34(2):225–228. doi: 10.1007/BF01536055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarfeh IJ, Tarnawski A. Gastric mucosal vasculopathy in portal hypertension. Gastroenterology. 1987 Nov;93(5):1129–1131. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90579-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2005 Jul;43(1):167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (B)28.Stewart CA, Sanyal AJ. Grading portal gastropathy: validation of a gastropathy scoring system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Aug;98(8):1758–1765. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canlas KR, Dobozi BM, Lin S, et al. Using capsule endoscopy to identify GI tract lesions in cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension and chronic anemia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008 Aug;42(7):844–848. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318038d312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barakat M, Mostafa M, Mahran Z, Soliman AG. Portal hypertensive duodenopathy: clinical, endoscopic, and histopathologic profiles. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Dec;102(12):2793–2802. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erden A, Idilman R, Erden I, Ozden A. Veins around the esophagus and the stomach: do their calibrations provide a diagnostic clue for portal hypertensive gastropathy? Clin Imaging. 2009 Jan-Feb;33(1):22–24. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishihara K, Ishida R, Saito T, Teramoto K, Hosomura Y, Shibuya H. Computed tomography features of portal hypertensive gastropathy. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004 Nov-Dec;28(6):832–835. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200411000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Franchis R, Eisen GM, Laine L, et al. Esophageal capsule endoscopy for screening and surveillance of esophageal varices in patients with portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2008 May;47(5):1595–1603. doi: 10.1002/hep.22227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (A)34.Perez-Ayuso RM, Pique JM, Bosch J, et al. Propranolol in prevention of recurrent bleeding from severe portal hypertensive gastropathy in cirrhosis. Lancet. 1991 Jun 15;337(8755):1431–1434. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93125-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (B)35.Gostout CJ, Viggiano TR, Balm RK. Acute gastrointestinal bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy: prevalence and clinical features. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993 Dec;88(12):2030–2033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosking SW. Congestive gastropathy in portal hypertension: variations in prevalence. Hepatology. 1989 Aug;10(2):257–258. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840100223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagatsuma Y, Naritaka Y, Shimakawa T, et al. Clinical usefulness of the angiotensin II receptor antagonist losartan in patients with portal hypertensive gastropathy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006 Mar-Apr;53(68):171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karajeh MA, Hurlstone DP, Stephenson TJ, Ray-Chaudhuri D, Gleeson DC. Refractory bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy: a further novel role for thalidomide therapy? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 May;18(5):545–548. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200605000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cremers MI, Oliveira AP, Alves AL, Freitas J. Portal hypertensive gastropathy: treatment with corticosteroids. Endoscopy. 2002 Feb;34(2):177. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-19848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (B)40.Kamath PS, Lacerda M, Ahlquist DA, McKusick MA, Andrews JC, Nagorney DA. Gastric mucosal responses to intrahepatic portosystemic shunting in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2000 May;118(5):905–911. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mezawa S, Homma H, Ohta H, et al. Effect of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt formation on portal hypertensive gastropathy and gastric circulation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Apr;96(4):1155–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Urata J, Yamashita Y, Tsuchigame T, et al. The effects of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt on portal hypertensive gastropathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998 Oct;13(10):1061–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vignali C, Bargellini I, Grosso M, et al. TIPS with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent: results of an Italian multicenter study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005 Aug;185(2):472–480. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orloff MJ, Orloff MS, Orloff SL, Haynes KS. Treatment of bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy by portacaval shunt. Hepatology. 1995 Apr;21(4):1011–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soin AS, Acharya SK, Mathur M, Sahni P, Nundy S. Portal hypertensive gastropathy in noncirrhotic patients. The effect of lienorenal shunts. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998 Jan;26(1):64–67. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199801000-00017. discussion 68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herrera S, Bordas JM, Llach J, et al. The beneficial effects of argon plasma coagulation in the management of different types of gastric vascular ectasia lesions in patients admitted for GI hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008 Sep;68(3):440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007 Sep;46(3):922–938. doi: 10.1002/hep.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernandez J, Ruiz del Arbol L, Gomez C, et al. Norfloxacin vs ceftriaxone in the prophylaxis of infections in patients with advanced cirrhosis and hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2006 Oct;131(4):1049–1056. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.010. quiz 1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (A)49.Villanueva C, Planella M, Aracil C, et al. Hemodynamic effects of terlipressin and high somatostatin dose during acute variceal bleeding in nonresponders to the usual somatostatin dose. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Mar;100(3):624–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (A)50.Cirera I, Feu F, Luca A, et al. Effects of bolus injections and continuous infusions of somatostatin and placebo in patients with cirrhosis: a double-blind hemodynamic investigation. Hepatology. 1995 Jul;22(1):106–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (A)51.Bruha R, Marecek Z, Spicak J, et al. Double-blind randomized, comparative multicenter study of the effect of terlipressin in the treatment of acute esophageal variceal and/or hypertensive gastropathy bleeding. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002 Jul-Aug;49(46):1161–1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (B)52.Zhou Y, Qiao L, Wu J, Hu H, Xu C. Comparison of the efficacy of octreotide, vasopressin, and omeprazole in the control of acute bleeding in patients with portal hypertensive gastropathy: a controlled study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002 Sep;17(9):973–979. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kouroumalis EA, Koutroubakis IE, Manousos ON. Somatostatin for acute severe bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998 Jun;10(6):509–512. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199806000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gostout CJ, Viggiano TR, Ahlquist DA, Wang KK, Larson MV, Balm R. The clinical and endoscopic spectrum of the watermelon stomach. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992 Oct;15(3):256–263. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199210000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tobin RW, Hackman RC, Kimmey MB, et al. Bleeding from gastric antral vascular ectasia in marrow transplant patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996 Sep;44(3):223–229. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liberski SM, McGarrity TJ, Hartle RJ, Varano V, Reynolds D. The watermelon stomach: long-term outcome in patients treated with Nd:YAG laser therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994 Sep-Oct;40(5):584–587. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(94)70258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamamoto M, Takahashi H, Akaike J, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) associated with systemic sclerosis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2008 Jul-Aug;37(4):315–316. doi: 10.1080/03009740801998754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dulai GS, Jensen DM, Kovacs TO, Gralnek IM, Jutabha R. Endoscopic treatment outcomes in watermelon stomach patients with and without portal hypertension. Endoscopy. 2004 Jan;36(1):68–72. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Payen JL, Cales P, Voigt JJ, et al. Severe portal hypertensive gastropathy and antral vascular ectasia are distinct entities in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1995 Jan;108(1):138–144. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lecleire S, Ben-Soussan E, Antonietti M, et al. Bleeding gastric vascular ectasia treated by argon plasma coagulation: a comparison between patients with and without cirrhosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008 Feb;67(2):219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ward EM, Raimondo M, Rosser BG, Wallace MB, Dickson RD. Prevalence and natural history of gastric antral vascular ectasia in patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004 Nov-Dec;38(10):898–900. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200411000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spahr L, Villeneuve JP, Dufresne MP, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia in cirrhotic patients: absence of relation with portal hypertension. Gut. 1999 May;44(5):739–742. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.5.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vincent C, Pomier-Layrargues G, Dagenais M, et al. Cure of gastric antral vascular ectasia by liver transplantation despite persistent portal hypertension: a clue for pathogenesis. Liver Transpl. 2002 Aug;8(8):717–720. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.34382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saperas E, Perez Ayuso RM, Poca E, Bordas JM, Gaya J, Pique JM. Increased gastric PGE2 biosynthesis in cirrhotic patients with gastric vascular ectasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990 Feb;85(2):138–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Charneau J, Petit R, Cales P, Dauver A, Boyer J. Antral motility in patients with cirrhosis with or without gastric antral vascular ectasia. Gut. 1995 Oct;37(4):488–492. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.4.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burak KW, Lee SS, Beck PL. Portal hypertensive gastropathy and gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) syndrome. Gut. 2001 Dec;49(6):866–872. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.6.866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Suit PF, Petras RE, Bauer TW, Petrini JL., Jr. Gastric antral vascular ectasia. A histologic and morphometric study of “the watermelon stomach”. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987 Oct;11(10):750–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Labenz J, Borsch G. Bleeding watermelon stomach treated by Nd-YAG laser photocoagulation. Endoscopy. 1993 Mar;25(3):240–242. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mathou NG, Lovat LB, Thorpe SM, Bown SG. Nd:YAG laser induces long-term remission in transfusion-dependent patients with watermelon stomach. Lasers Med Sci. 2004;18(4):213–218. doi: 10.1007/s10103-003-0284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Selinger RR, McDonald GB, Hockenbery DM, Steinbach G, Kimmey MB. Efficacy of neodymium:YAG laser therapy for gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) following hematopoietic cell transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006 Jan;37(2):191–197. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ng I, Lai KC, Ng M. Clinical and histological features of gastric antral vascular ectasia: successful treatment with endoscopic laser therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996 Mar;11(3):270–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1996.tb00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sato T, Yamazaki K, Toyota J, et al. Efficacy of argon plasma coagulation for gastric antral vascular ectasia associated with chronic liver disease. Hepatol Res. 2005 Jun;32(2):121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yusoff I, Brennan F, Ormonde D, Laurence B. Argon plasma coagulation for treatment of watermelon stomach. Endoscopy. 2002 May;34(5):407–410. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-25287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sebastian S, McLoughlin R, Qasim A, O’Morain CA, Buckley MJ. Endoscopic argon plasma coagulation for the treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach): long-term results. Dig Liver Dis. 2004 Mar;36(3):212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2003.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Roman S, Saurin JC, Dumortier J, Perreira A, Bernard G, Ponchon T. Tolerance and efficacy of argon plasma coagulation for controlling bleeding in patients with typical and atypical manifestations of watermelon stomach. Endoscopy. 2003 Dec;35(12):1024–1028. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-44594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (B)76.Kwan V, Bourke MJ, Williams SJ, et al. Argon plasma coagulation in the management of symptomatic gastrointestinal vascular lesions: experience in 100 consecutive patients with long-term follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006 Jan;101(1):58–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Probst A, Scheubel R, Wienbeck M. Treatment of watermelon stomach (GAVE syndrome) by means of endoscopic argon plasma coagulation (APC): long-term outcome. Z Gastroenterol. 2001 Jun;39(6):447–452. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-15722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Serrani M, et al. Endoscopic argon plasma coagulation for the treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia-related bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis. Digestion. 2009;79(3):143–150. doi: 10.1159/000210087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baudet JS, Salata H, Soler M, et al. Hyperplastic gastric polyps after argon plasma coagulation treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) Endoscopy. 2007 Feb;39(Suppl 1):E320. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Izquierdo S, Rey E, Gutierrez Del Olmo A, Almansa C, Andres Ramirez Armengol J, Diaz-Rubio M. Polyp as a complication of argon plasma coagulation in watermelon stomach. Endoscopy. 2005 Sep;37(9):921. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Farooq FT, Wong RC, Yang P, Post AB. Gastric outlet obstruction as a complication of argon plasma coagulation for watermelon stomach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007 Jun;65(7):1090–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Petrini JL, Jr., Johnston JH. Heat probe treatment for antral vascular ectasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989 Jul-Aug;35(4):324–328. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(89)72802-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kantsevoy SV, Cruz-Correa MR, Vaughn CA, Jagannath SB, Pasricha PJ, Kalloo AN. Endoscopic cryotherapy for the treatment of bleeding mucosal vascular lesions of the GI tract: a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003 Mar;57(3):403–406. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cho S, Zanati S, Yong E, et al. Endoscopic cryotherapy for the management of gastric antral vascular ectasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008 Nov;68(5):895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.03.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wells CD, Harrison ME, Gurudu SR, et al. Treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) with endoscopic band ligation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008 Aug;68(2):231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gill KR, Raimondo M, Wallace MB. Endoscopic band ligation for the treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009 May;69(6):1194. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tran A, Villeneuve JP, Bilodeau M, et al. Treatment of chronic bleeding from gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) with estrogen-progesterone in cirrhotic patients: an open pilot study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999 Oct;94(10):2909–2911. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Manning RJ. Estrogen/progesterone treatment of diffuse antral vascular ectasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995 Jan;90(1):154–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moss SF, Ghosh P, Thomas DM, Jackson JE, Calam J. Gastric antral vascular ectasia: maintenance treatment with oestrogen-progesterone. Gut. 1992 May;33(5):715–717. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.5.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nardone G, Rocco A, Balzano T, Budillon G. The efficacy of octreotide therapy in chronic bleeding due to vascular abnormalities of the gastrointestinal tract. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999 Nov;13(11):1429–1436. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bhowmick BK. Watermelon stomach treated with oral corticosteroid. J R Soc Med. 1993 Jan;86(1):52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Suzuki T, Hirano M, Oka H. Long-term corticosteroid therapy for gastric antral vascular ectasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996 Sep;91(9):1873–1874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McCormick PA, Ooi H, Crosbie O. Tranexamic acid for severe bleeding gastric antral vascular ectasia in cirrhosis. Gut. 1998 May;42(5):750–752. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.5.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dunne KA, Hill J, Dillon JF. Treatment of chronic transfusion-dependent gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) with thalidomide. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Apr;18(4):455–456. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200604000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cabral JE, Pontes JM, Toste M, et al. Watermelon stomach: treatment with a serotonin antagonist. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991 Jul;86(7):927–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shibukawa G, Irisawa A, Sakamoto N, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) associated with systemic sclerosis: relapse after endoscopic treatment by argon plasma coagulation. Intern Med. 2007;46(6):279–283. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mann NS, Rachut E. Gastric antral vascular ectasia causing severe hypoalbuminemia and anemia cured by antrectomy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002 Mar;34(3):284–286. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200203000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pljesa S, Golubovic G, Tomasevic R, Markovic R, Perunicic G. “Watermelon stomach” in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Ren Fail. 2005;27(5):643–646. doi: 10.1080/08860220500200890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jabbari M, Cherry R, Lough JO, Daly DS, Kinnear DG, Goresky CA. Gastric antral vascular ectasia: the watermelon stomach. Gastroenterology. 1984 Nov;87(5):1165–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]