Abstract

This article provides an overview of the characteristics of adolescent alcohol use, normative and subgroup variations in drinking behavior, and important factors associated with an increased risk for developing alcohol problems in later adolescence and young adulthood. A parental/family history of alcoholism, temperament traits, conduct problems, cognitive functioning, alcohol expectancies, and peer and other social relations are identified as influencing an adolescent’s susceptibility for initiating a variety of alcohol use behaviors. The Deviance Prone Model, proposed by Sher (1991), is presented as an important tool for testing possible relationships among the various risk factors and their sequencing that leads to early adolescent alcohol and drug initiation and use. It is also possible to extend the model to allow for an examination of the complex interplay of risk factors that leads to the development of alcohol use problems in late adolescence and young adults.

Keywords: Adolescents, alcohol use, vulnerability factors, deviance proneness

Early adolescence is the key developmental period for the initiation of alcohol use that progresses on to regular use and problem drinking in mid- and later adolescence and young adulthood. This article provides an overview of the characteristics of adolescent alcohol use, normative and subgroup variations in drinking, and the factors associated with increased risk for developing alcohol problems. We present the Deviance Prone Model as a tool for examining the complex interactions between the risk factors reviewed.

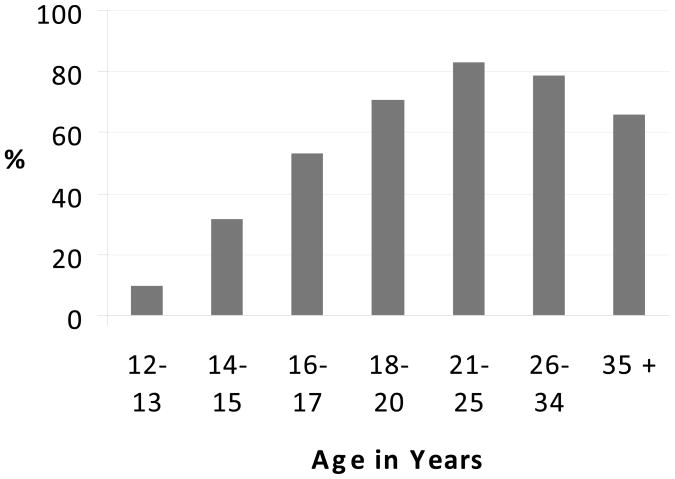

Early adolescence (ages 10–15 years) is associated with first alcohol use. Findings from 3 national surveys point to the 7th and 8th grades, when students are typically 13–14 years old, as the peak years for the initiation of alcohol use 1. Late adolescence (ages 16–20 years) is characterized by more risky alcohol use patterns, including binge drinking (i.e., consuming 5+ drinks on a single occasion). Normative rates of youth drinking increase with age, accelerating among older adolescents and leveling off in the twenties at around ages 21–22 years for heavy drinking and 25–26 years for current drinking 2–3. Figure 1 shows past year rates of drinking based on the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) for the U.S. population. The highest incidence and prevalence of alcohol abuse and dependence is seen in those drinkers ages 18–23, followed by ages 12–17 years 4.

Figure 1.

U.S. prevalence of past year drinking: ages 12 years and older.

Note. Source: 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Office of Applied Studies.

Variations in Adolescent Drinking

Alcohol use behaviors vary by several sociodemographic characteristics, including ethnicity and gender, during adolescence 5. Table 1 provides estimates of 30-day alcohol use and binge drinking and the age of first use for the three largest U.S. ethnic groups. According to the 2007 NSDUH, the prevalences of 30-day alcohol use and binge drinking were highest for Whites, followed by Hispanics and then Blacks. Relative to Blacks, Hispanics and Whites had somewhat earlier ages of drinking onset. Gender differences in the rate of 30-day alcohol use varies by ethnic group (i.e., White males = White females, Black females < Black males, and Hispanic females > Hispanic males), but binge drinking was more prevalent in males than females for all ethnic groups. Females, particularly Black females, also showed a later age of first alcohol use compared to males.

Table 1.

U.S. Ethnic Group and Gender Variations in Alcohol Use: Youth Ages 12 to 20 Years

| 2007 | 2005–2007 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % 30-day Alcohol Use |

% 30-day Binge Drinking |

Mean Age of 1st Use |

||||

| M | F | M | F | M | F | |

| White a | 32.8 (0.9) | 31.3 (0.8) | 24.8 (0.7) | 19.4 (0.7) | 13.95 (0.04) | 14.10 (0.03) |

| Black a | 17.3 (1.2) | 20.2 (1.3) | 9.2 (0.9) | 7.1 (0.8) | 14.22 (0.09) | 14.35 (0.10) |

| Hispanic | 27.5 (1.4) | 23.4 (1.1) | 19.2 (1.3) | 12.3 (1.2) | 13.84 (0.10) | 14.08 (0.07) |

Note: M = male; F = female;

Non-Hispanic;

Estimates are % or Mean (standard error) as specified; Source: Chen, C.M., Yi, H., Williams, G.D., & Faden, V.B. (2009). Surveillance report #86, trends in underage drinking in the United Sates, 1991–2007. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Regardless, recent research findings suggest that the gender gap in drinking behaviors has narrowed. Several studies have demonstrated secular trends in alcohol use behavior. More recently, Grucza et al. 6 showed an increase in the risk for drinking and alcohol dependence among women born after World War II. These changes were observed for White and Hispanic females, but not Black females, and are attributed to a sharper decrease in the age of onset of drinking for women compared to men born between 1954 and 1983 7. Consequently, early onset alcohol use is associated with the early development of a variety of alcohol use problems and a more severe course of alcohol dependence 8–10. Adolescent drinking behaviors appear to dependably predict later drinking and drinking problems in young adulthood 11.

Different trajectories of alcohol use (i.e., patterns of drinking overtime) have been identified among adolescents once drinking begins. Maggs and Schulenberg 12 summarized several adolescent drinking trajectories into young adulthood, including a stable abstainer/low-risk drinking course, a chronic heavy use course, a late-onset heavy use course, and a developmentally-limited drinking course. Most adolescents drink at low-risk levels or age out of alcohol involvement as they transition toward family and career, but others adolescents do not (i.e., those in the chronic and late-onset heavy use groups). A variety of explanatory factors for to the development of alcohol problems have been proposed. A family history of alcoholism, temperament traits, cognitive functioning, conduct problems, and peer and family relationships are among the factors most frequently cited as being associated with an increased risk for adolescent alcohol use and problem drinking. These are reviewed below.

Risk Factors for Problem Drinking

Family History of Alcoholism

A variety of family pedigree, twin, and adoption studies have provided significant evidence of an increased risk for developing alcohol problems when a biological parent is affected. The nature of the risk due to a family history of alcoholism has been decomposed into genetic and environmental factors 10, 13. Although the proportion of the risk for developing alcohol dependence determined by either environmental or genetic factors has not been conclusively determined, it appears that genetic factors account for about 50% of the variance 13. Twin, sibling pair, family (e.g., Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA)) and case-control studies are currently ongoing to identify candidate genes related to susceptibility for developing alcoholism. Among others, GABRA2, CHRM2, and ADH4 are associated with alcohol dependence for adults in the COGA study, findings that have been replicated by other researchers in other samples 14–15.

High risk environments may also interact with genetic vulnerability to increase an individual’s risk of alcohol dependence. Stressful life events, childhood maltreatment, family violence and poor social support combined with genetic vulnerability are associated with increased risk for alcoholism, depressive symptoms and conduct problems 16. Dick et al. 17–18 showed that genetic influences on adolescent substance use were enhanced in environments characterized by lower parental monitoring and substance-using friends. Genetic influences appear to have larger effects on the development of drinking frequency and alcohol dependence, while the onset of drinking is largely impacted by environmental factors 19–20.

Temperament Traits

Temperament has been identified as an important contributor to several theoretical formulations related to the development of alcohol use behaviors, including problem drinking 21–22. While prior research has shown that the vulnerability for the development of alcoholism lies, in part, in an individual’s genetic makeup, several studies suggest that this genetic propensity may be partially expressed through the individual’s temperament. Temperament is a set of behavioral and emotional reactions that varies among individuals, has moderate temporal and situational stability, and appears early in childhood 23. In particular, behavioral undercontrol and negative affectivity, as temperament traits, have been linked to the development of alcohol use problems.

Behavioral undercontrol is often conceived as including a wide range of traits, e.g., aggressiveness, delinquency, impulsivity, risk-taking, sensation seeking and disinhibition 11. Further, the propensity to be disinhibited or easily bored may encourage the expression of externalizing behaviors i.e., conduct problems, alcohol and drug use; 24, 25–26. For example, a negative association between age of first drink and disinhibitory behavior, including oppositionality, impulsiveness, and inattention assessed at age 11 to predict alcohol use at age 14 was reported by McGue and colleagues 27. Similarly, higher levels of disinhibition, risk taking and boredom susceptibility also predict an earlier age of regular alcohol use, earlier marijuana use, and more frequent drinking 28. Behavior undercontrol may affect alcohol involvement and an earlier onset of adolescent substance use by increasing conduct problems and positive expectancies for alcohol consumption 29–30.

Negative affectivity (i.e., the tendency toward depression and neuroticism; internalizing behaviors) has been found to be over represented in samples of offspring of alcoholics and individuals who later become alcoholic 31. Some individuals may use drugs and alcohol to cope with and relieve the unpleasant symptoms of negative affect 32–33. However, the evidence supporting the role of negative affectivity as a contributor to the development of alcohol and drug involvement is inconsistent 11. Ohannessian and Hesselbrock 29, 34 found no effect of negative affect in predicting substance use in high risk adolescents, while conduct problems and risk taking did play significant roles. Negative affectivity did not predict the age of onset of alcohol use, but predicted conduct problems and the quantity and frequency of drinking once drinking behavior and problems were established among adolescents 35. Further, different components of negative affect (i.e., sadness, fear, guilt, and hostility) appear to differentially affect substance use in adolescents, with higher levels of hostility and lower levels of guilt associated with earlier marijuana use initiation in adolescents 36.

Conduct Problems

Both cross-sectional 37–38 and longitudinal investigations have found that childhood conduct problems predict alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among adolescents and young adults 39–42. Typically, both boys and girls with conduct problems have an early onset of alcohol and substance use problems and often manifest a more chronic and severe course of the disorder that continues well into middle age 35, 43–45. Further, when childhood and adolescent conduct problems lead to adult Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD), the effects of ASPD on both the course and consequences of alcoholism are independent and additive to the effects of a family history of alcoholism 43, 46–47.

Childhood conduct disorder, like alcoholism, may not be a homogeneous disorder. A study of conduct problems among a community sample of girls found group differences in relation to symptom severity. Minimal or mild symptoms among girls typically show a developmental trajectory with possible dissipation of symptoms during adolescence and young adulthood. Girls having more severe symptoms in childhood continued to display disruptive behaviors well into adolescence and were at increased risk for developing DSM-III-R conduct disorder 48. Further, for both adult men and women, the more severe the subtype of conduct or antisocial behavior, the earlier the onset of alcohol/drug use and the more severe the substance dependence problems 49–50. The relationship of childhood conduct problems to adolescent drinking behaviors may also vary by ethnic group. Increased childhood conduct problems predicted an earlier age of regular drinking onset for Blacks, but not for Whites and Hispanics 51. In general, studies of both clinical and non-clinical samples have found a positive association between frequency of childhood conduct problems and an early onset of alcohol/drug use. Clearly, though, not all persons with childhood conduct problems go on to develop alcohol use problems.

Cognitive Functioning

Neuropsychological deficiencies (e.g., impulsivity, inability to use language to cognitively regulate behavior, and poor foresight) may influence the development of alcohol problems by compromising educational attainment and impairing psychosocial development among high risk individuals. Differences in cognitive functioning as measured by electroencephalographic and event-related potential (EEG/ERP) methods have been reported among children and adolescents at risk for developing alcoholism prior to the onset of heavy drinking 52–53. The age of first drink was associated with a reduced P300 ERP amplitude in 17 year old twins 27. Similarly, a reduced P300 amplitude and deficits in reading achievement predicted an early onset of drinking, separate from the contribution of familial density for alcoholism 54. Differences in EEG and ERP brainwave patterns are typically found in the frontal brain region 55, an area thought to be responsible for the cognitive skills of attention, planning and foresight. Tests of frontal and temporal lobe functioning among high risk young adult males were predictive of the age of first drink initiation and the frequency of drinking to intoxication 56–57. However, some studies have failed to find an association between poor cognitive skills and alcohol use. For example, Sher et al. 30 showed that cognitive functioning as measured by verbal ability did not predict alcohol involvement in college students with a family history of alcoholism.

Alcohol Expectancies

The role of expectancies has been demonstrated in the production of a variety of behaviors, including the affect of certain positive and negative expectations of the effects of alcohol on alcohol use 58–59. Social Learning theory suggests that expectancies about alcohol’s effects on sexual enhancement, physical and social pleasure, increased social assertiveness, and relaxation 60 likely reflect not only a person’s own experience with alcohol, but also result from exposure to beverage alcohol advertising and from observing the behavior of others when they are drinking. Repeated exposure to these events can begin even in childhood. For example, the positive expectancies of alcohol’s effects among elementary school children have been found to increase across the first through fifth grades, most notably among 8–10 year olds 61. Shifts in alcohol expectancies occurring later in childhood typically reflect the changes in alcohol involvement observed across age groups. Positive alcohol expectancies increase during adolescence, but decrease in early adulthood 62. Similarly, positive alcohol expectancy appears to be a better predictor of drinking among individuals prior to 35 years of age, while negative alcohol expectancy better predicts drinking status for most individuals over 35 years 63.

Importantly, though, positive expectancies of alcohol’s effects do predict the initiation of drinking, intention to drink, and drinking rates among both middle school 64 and college students 65. Previous studies of college-aged offspring of an alcoholic parent have identified alcohol expectancies as a key mediator for a family history of alcoholism and behavioral undercontrol in predicting alcohol involvement, relationships that hold equally for males and females 30. Differences by race and grade, but not by gender, have been reported in the relationships between alcohol expectancies and alcohol use in children from 6th, 8th, and 11th grades 66. Positive alcohol expectancies showed a stronger positive association in predicting alcohol use initiation for older compared to younger adolescents, and for White and Hispanic adolescents in predicting alcohol initiation, drinking and binge-drinking. Chartier et al. 51 similarly reported a stronger association for White and Hispanic adolescents compared to Black adolescents in the relationship of alcohol expectancies to age of regular drinking onset.

Peer and Other Social Relations

Those to whom one can turn in times of trouble and to whom a person can confidently expect caring, valuing and love can be defined as a social network. A strong social network has been reported to decrease the vulnerability to both mental and physical health problems, help moderate the need for medication, and help an individual recover more quickly following an illness 67–68. Conversely, an increase in health problems has been reported in the context of high life stresses in the absence of social support 67. The role of social support both from family 69–70 and from friends 70–72 has been examined in relation to the initiation of alcohol use, maintenance of drinking behavior, and onset of alcohol-related problem behaviors among both alcoholics and adolescents susceptible to developing alcoholism. The relationship of family and peer social support to alcohol and drug use in adolescents has been examined 73. Adolescents reporting heavy marijuana and tobacco use perceived lower social support from friends and family compared to light users, while heavy alcohol users compared to light drinkers reported higher social support from friends. The connection between social relationships with peers and adolescent alcohol use is complex, as a certain level of alcohol involvement may indicate greater social success while non-use may be associated with less social success with peers 11.

Three forms of peer influence have been suggested as contributing to the risk for adolescent alcohol use and problems: 1) the direct modeling or encouragement of alcohol use, 2) a self-sustaining affiliation with like-minded peers, and 3) the overestimation by adolescents of the prevalence of their peers’ drinking 74. Older siblings and parents may similarly influence adolescent alcohol and drug use through modeling, approval of drinking and also provide access to alcohol 74–75. Further, family relationships, parenting styles and other family-related factors may affect adolescent alcohol initiation, use and the development of problems. Adolescent at-risk children living apart from their biological father were shown to fare worse than those living with him in terms of increased conduct problems and an earlier onset of alcohol and drug use 76. Kramer et al. 77 similarly identified an adolescent’s relationship with his/her father as an important predictor of alcohol symptoms in young adults; a negative relationship with the father predicted increased alcohol symptoms in adulthood. Poor family management, inconsistent discipline, and inadequate supervision and monitoring among parents with an alcohol use disorder are also associated with increased problem behaviors in children 78.

The Deviance Prone Model

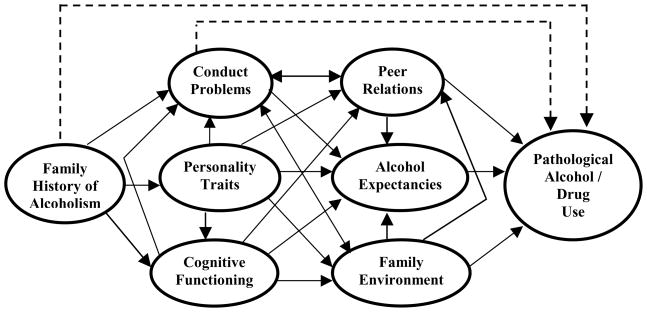

A single vulnerability factor may be insufficient to precipitate problematic alcohol involvement in an adolescent. More likely, multiple factors act synergistically to increase the probability of an adolescent developing alcohol problems. A variety of different theoretical models, using the risk factors cited above, have been proposed over time to explain the initiation and development of alcohol use and problems in adolescence. Typically these models include a parental history of alcoholism, peer influences, externalizing behaviors, internalizing behaviors, and environmental and biological factors as risk factors 11, 21, 35, 78–79. One of the more frequently cited models uses early childhood conduct problems or the propensity for deviant behavior as a major explanatory variable. The “Deviance Prone” Model (see Figure 2) examines the complex interactions between a family history of alcoholism and mediating factors in predicting alcohol use problems. Sher 32 originally proposed the model as a heuristic device to examine the development of pathological alcohol use. Many elements of the model have also been widely cited in the literature as predictors of both an early onset and early regular use of alcohol and other drug use among adolescents.

Figure 2.

Deviance prone model of vulnerability.

‘Proneness’ is defined as the likelihood of occurrence of a normative transgression or problem behavior 80. Early and regular adolescent drinking are problem behaviors that frequently co-occur with other problem behaviors, including tobacco and marijuana use, sexual behavior and delinquency. Donovan and Jessor 81 suggest that ‘unconventionality’, a common factor, underlies these problem behaviors. ‘Unconventionallity’ is defined by placing a lower value on academic achievement, a greater tolerance of deviance, having a greater orientation toward friends versus family, and perceiving parental and friends’ approval of problem behavior. The major features of the Deviance Prone Model (i.e., parental history of alcoholism, certain temperament traits, childhood conduct problems, cognitive difficulties, alcohol expectancies, and social relations) correspond with these and other characteristics of ‘unconventionality’ and theoretically link the liability of familial alcoholism to the development of alcohol-related problems.

Summary

This review of adolescent drinking demonstrates that alcohol use typically starts in early adolescence and increases with age into late adolescence and young adulthood. Ethnic and gender differences and different trajectories of alcohol use have been observed in large national epidemiological samples. However, most adolescents drink at low-risk levels and typically “mature out” of risky drinking patterns during their mid-twenties. Several putative susceptibility factors (i.e., family/parental alcoholism, behavioral undercontrol, childhood conduct problems, neuropsychological problems, alcohol expectancies, and peer and family relations) singly and in combination contribute to the initiation and frequency of alcohol use and to the development of alcohol use behavior, including pathological alcohol involvement. Further, some studies have found that other putative risk factors such as negative affectivity did not consistently contribute to youth drinking, but may be quite important in predicting continued heavy alcohol use or alcohol problem behavior in adulthood. Multiple risk factors likely interact with themselves, the environment and possibly genetic factors to increase the probability for alcohol problems developing in adolescence. The Deviance Prone Model provides an important tool for testing possible relationships and the sequencing of vulnerability factors for adolescent alcohol and drug use, and allows for an examination of the complex interplay of risk factors that lead to the development of alcoholism and related alcohol problems.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIAAA Grant No. P60AA03510.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Faden VB. Trends in initiation of alcohol use in the United States 1975 to 2003. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(6):1011–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CM, Dufour MC, Yi H. Alcohol consumption among young adults ages 18–24 in the United States: Results from the 2001–2002 NESARC survey. Alcohol Res Health. 2004/2005;28(4):269–280. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muthen BO, Muthen LK. The development of heavy drinking and alcohol-related problems from ages 18 to 37 in a U.S. national sample. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61(2):290–300. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harford TC, Grant BF, Yi HY, Chen CM. Patterns of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence criteria among adolescents and adults: results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(5):810–828. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164381.67723.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CM, Yi H, Williams GD, Faden VB. Surveillance report #86, trends in underage drinking in the United States, 1991–2007. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grucza RA, Bucholz KK, Rice JP, Bierut LJ. Secular trends in the lifetime prevalence of alcohol dependence in the United States: a re-evaluation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(5):763–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grucza RA, Norberg K, Bucholz KK, Bierut LJ. Correspondence between secular changes in alcohol dependence and age of drinking onset among women in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(8):1493–1501. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(7):739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Age at first drink and risk for alcoholism: a noncausal association. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23(1):101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zucker RA. Anticipating problem alcohol use developmentally from childhood into middle adulthood: what have we learned? Addiction. 2008;103 (Suppl 1):100–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maggs J, Schulenberg J. Trajectories of alcohol use during the transition to adulthood. Alcohol Res Health. 2004/2005;28(4):195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to alcohol dependence risk in a national twin sample: consistency of findings in women and men. Psychol Med. 1997;27(6):1381–1396. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edenberg HJ, Foroud T. The genetics of alcoholism: identifying specific genes through family studies. Addict Biol. 2006;11(3–4):386–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dick DM, Bierut LJ. The genetics of alcohol dependence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(2):151–157. doi: 10.1007/s11920-006-0015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enoch MA. Genetic and environmental influences on the development of alcoholism: resilience vs. risk. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1094:193–201. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dick DM, Pagan JL, Holliday C, et al. Gender differences in friends’ influences on adolescent drinking: a genetic epidemiological study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res Dec. 2007;31(12):2012–2019. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dick DM, Pagan JL, Viken R, et al. Changing environmental influences on substance use across development. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10(2):315–326. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dick DM, Bernard M, Aliev F, et al. The role of socioregional factors in moderating genetic influences on early adolescent behavior problems and alcohol use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(10):1739–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnow S, Schuckit MA, Lucht M, John U, Freyberger HJ. The importance of a positive family history of alcoholism, parental rejection and emotional warmth, behavioral problems and peer substance use for alcohol problems in teenagers: a path analysis. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(3):305–315. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarter RE, Vanyukov M. Alcoholism: a developmental disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62(6):1096–1107. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.6.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blackson TC. Temperament: a salient correlate of risk factors for alcohol and drug abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;36(3):205–214. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kagan J. Galen’s prophecy: Temperament in human nature. New York: Basic Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103(1):92–102. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarter RE, Laird SB, Kabene M, Bukstein O, Kaminer Y. Drug abuse severity in adolescents is associated with magnitude of deviation in temperament traits. Br J Addict. 1990;85(11):1501–1504. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Windle M. A longitudinal study of antisocial behaviors in early adolescence as predictors of late adolescent substance use: gender and ethnic group differences. J Abnorm Psychol. 1990;99(1):86–91. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Malone S, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink. I. Associations with substance-use disorders, disinhibitory behavior and psychopathology, and P3 amplitude. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(8):1156–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohannessian CM, Hesselbrock VM. Do personality characteristics and risk taking mediate the relationship between paternal substance dependence and adolescent substance use? Addict Behav. 2007;32(9):1852–1862. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohannessian CM, Hesselbrock VM. A comparison of three vulnerability models for the onset of substance use in a high-risk sample. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(1):75–84. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood PK, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(4):427–448. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnes GE. Clinical and personality characteristics. In: Begleiter H, editor. The pathogenesis of alcoholism: Psychosocial factors. Vol. 6. New York: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 113–196. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sher KJ. Children of alcoholics: A critical appraisal of theory and research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sher KJ, Levenson RW. Risk for alcoholism and individual differences in the stress-response-dampening effect of alcohol. J Abnorm Psychol. 1982;91(5):350–367. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.91.5.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohannessian CM, Hesselbrock VM. Paternal alcoholism and youth substance abuse: the indirect effects of negative affect, conduct problems, and risk taking. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(2):198–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuckit MA, Windle M, Smith TL, et al. Searching for the full picture: structural equation modeling in alcohol research. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(2):194–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohannessian CM, Hesselbrock VM. A finer examination of the role that negative affect plays in the relationship between paternal alcoholism and the onset of alcohol and marijuana use. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(3):400–408. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hesselbrock MN. Childhood behavior problems and adult antisocial personality disorder in alcoholism. In: Meyer RE, editor. Psychopathology and addictive disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 1986. pp. 78–94. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohannessian CM, Hesselbrock VM. An examination of the underlying influence of temperament and problem behaviors on drinking behaviors in a sample of adult offspring of alcoholics. Addict Behav. 1994;19(3):257–268. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuperman S, Chan G, Kramer JR, et al. Relationship of age of first drink to child behavioral problems and family psychopathology. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(10):1869–1876. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183190.32692.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Psychiatric comorbidity with problematic alcohol use in high school students. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(1):101–109. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199601000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown SA, Gleghorn A, Schuckit MA, Myers MG, Mott MA. Conduct disorder among adolescent alcohol and drug abusers. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57(3):314–324. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson EO, Arria AM, Borges G, Ialongo N, Anthony JC. The growth of conduct problem behaviors from middle childhood to early adolescence: sex differences and the suspected influence of early alcohol use. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56(6):661–671. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cadoret RJ, Yates WR, Troughton E, Woodworth G, Stewart MA. Adoption study demonstrating two genetic pathways to drug abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(1):42–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950130042005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robins LN. Deviant children grown up: A sociological and psychiatric study of sociopathic personality. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaillant GE. A long-term follow-up of male alcohol abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(3):243–249. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030065010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slutske WS, Heath AC, Dinwiddie SH, et al. Common genetic risk factors for conduct disorder and alcohol dependence. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(3):363–374. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hesselbrock VM, Hesselbrock MN. Alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder: Are they different? Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1994;(Supplement 2):479–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cote S, Zoccolillio M, Tremblay RE, Nagin D, Vitaro F. Predicting girls’ conduct disorder in adolescence from childhood trajectories of disruptive behaviors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(6):678–684. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200106000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cottler LB, Price RK, Compton WM, Mager DE. Subtypes of adult antisocial behavior among drug abusers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183(3):154–161. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bucholz KK, Hesselbrock VM, Heath AC, Kramer JR, Schuckit MA. A latent class analysis of antisocial personality disorder symptom data from a multi-centre family study of alcoholism. Addiction. 2000;95(4):553–567. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9545537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chartier KG, Hesselbrock MN, Hesselbrock VM. Ethnicity and adolescent pathways to alcohol use. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(3):337–345. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Begleiter H, Porjesz B, Bihari B, Kissin B. Event-related brain potentials in boys at risk for alcoholism. Science. 1984;225(4669):1493–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.6474187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bauer LO, Hesselbrock VM. Subtypes of family history and conduct disorder: effects on P300 during the stroop test. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(1):51–62. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hill SY, Shen S, Lowers L, Locke J. Factors predicting the onset of adolescent drinking in families at high risk for developing alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(4):265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00841-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bauer LO, Hesselbrock VM. CSD/BEM localization of P300 sources in adolescents “at-risk”: evidence of frontal cortex dysfunction in conduct disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50(8):600–608. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hesselbrock V, Bauer LO, Hesselbrock MN, Gillen R. Neuropsychological factors in individuals at high risk for alcoholism. Recent Dev Alcohol. 1991;9:21–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deckel AW, Hesselbrock V, Bauer L. Relationship between alcohol-related expectancies and anterior brain functioning in young men at risk for developing alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19(2):476–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brown SA, Goldman MS, Christiansen BA. Do alcohol expectancies mediate drinking patterns of adults? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53(4):512–519. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.4.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown SA, Christiansen BA, Goldman MS. The Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire: an instrument for the assessment of adolescent and adult alcohol expectancies. J Stud Alcohol. 1987;48(5):483–491. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller PM, Smith GT, Goldman MS. Emergence of alcohol expectancies in childhood: a possible critical period. J Stud Alcohol. 1990;51(4):343–349. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sher KJ, Gotham HJ. Pathological alcohol involvement: a developmental disorder of young adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11(4):933–956. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leigh BC, Stacy AW. Alcohol expectancies and drinking in different age groups. Addiction. 2004;99(2):215–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Christiansen BA, Smith GT, Roehling PV, Goldman MS. Using alcohol expectancies to predict adolescent drinking behavior after one year. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57(1):93–99. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stacy AW, Widaman KF, Marlatt GA. Expectancy models of alcohol use. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58(5):918–928. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.5.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meier MH, Slutske WS, Arndt S, Cadoret RJ. Positive alcohol expectancies partially mediate the relation between delinquent behavior and alcohol use: generalizability across age, sex, and race in a cohort of 85,000 Iowa schoolchildren. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21(1):25–34. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sarason B, Sarason I, Pierce G. Social Support. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Holahan CJ, Moos RH. Risk, resistance, and psychological distress: a longitudinal analysis with adults and children. J Abnorm Psychol. 1987;96(1):3–13. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wolin SJ, Bennett LA, Noonan DL, Teitelbaum MA. Disrupted family rituals; a factor in the intergenerational transmission of alcoholism. J Stud Alcohol. 1980;41(3):199–214. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1980.41.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jacob T, Krahn GL, Leonard K. Parent-child interactions in families with alcoholic fathers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59(1):176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Windle M. The difficult temperament in adolescence: associations with substance use, family support, and problem behaviors. J Clin Psychol. 1991;47(2):310–315. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199103)47:2<310::aid-jclp2270470219>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zucker RA, Gomberg ES. Etiology of alcoholism reconsidered. The case for a biopsychosocial process. Am Psychol. 1986;41(7):783–793. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.41.7.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Averna S, Hesselbrock V. The relationship of perceived social support to substance use in offspring of alcoholics. Addict Behav. 2001;26(3):363–374. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brown SA, McGue M, Maggs J, et al. A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics. 2008;121 (Suppl 4):S290–310. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Donovan JE. Adolescent alcohol initiation: a review of psychosocial risk factors. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(6):529, e527–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Averna S, Hesselbrock V. Parenting style moderates familial risk and adolescent outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(5):45A. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kramer JR, Chan G, Dick DM, et al. Multiple-domain predictors of problematic alcohol use in young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(5):649–659. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sher KJ, Grekin ER, Williams NA. The development of alcohol use disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:493–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brook JS, Whiteman M, Finch SJ, Cohen P. Young adult drug use and delinquency: childhood antecedents and adolescent mediators. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(12):1584–1592. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199612000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jessor R. Problem-behavior theory, psychosocial development, and adolescent problem drinking. Br J Addict. 1987;82(4):331–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Donovan JE, Jessor R. Structure of problem behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53(6):890–904. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.6.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]