Abstract

Purpose

Randomized trials comparing autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) to conventional chemotherapy have demonstrated superior survival among HIV negative ASCT patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Recent trials explored the feasibility of ASCT in the HIV setting. While these studies have shown that ASCT in HIV positive NHL patients (HIVpos-NHL) is well tolerated, the impact of HIV infection on long-term transplant outcome is not well characterized. Ongoing comparison of long-term survival following ASCT in HIVpos-NHL patients and HIVneg-NHL patients will allow investigators to explore whether there should be inclusion of HIVpos-NHL patients in ASCT trials.

Patients and Methods

To study long-term outcome we conducted a single institution matched case-control study in HIVpos-NHL patients (cases) and HIVneg-NHL patients (controls). Twenty-nine patients with HIVpos-NHL were matched with HIVneg-NHL controls on gender, time to ASCT, year of transplant, histology, age, disease status, number prior regimens, and conditioning regimen.

Results

Non-relapse mortality was similar: 11% (95%CI: 4–28%) in HIVpos-NHL patients and 4% (95%CI: 1–25%) in HIVneg-NHL controls (p=0.18). Two year DFS for the HIVpos-NHL patients was 76% (95%CI: 62–85%) and 56% (95%CI: 45–66%) for the HIVneg-NHL controls (p=0.33). OS was also similar; the two-year point estimates were 75% (95%CI: 61–85%) and 75% (95%CI: 60–85%) respectively (p=0.93), despite inclusion of more poor risk HIVpos-NHL patients.

Conclusion

These results provide further evidence that HIV status does not affect the long-term outcome of ASCT for NHL and therefore HIV status alone should no longer exclude these patients from transplant clinical trials.

Keywords: HIV, Autologous Transplantation, Non- Hodgkin Lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

Although survival of HIV infected patients has increased since the advent of effective anti-retroviral therapy (1), AIDS related malignancies remain a leading cause of mortality (2). Prior to the development of effective anti-retroviral therapy, the prognosis for patients with AIDS related lymphoma (ARL) was extremely poor. This was due to factors such as: advanced stage of disease at the time of diagnosis, highly aggressive histologies, and inability to tolerate intensive chemotherapy due to poor hematologic reserve and frequent opportunistic infections (3,4).

In the era of highly active anti-retroviral (HAART) therapy, treatment with standard doses of chemotherapy such as R-CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin vincristine, prednisone, plus rituximab) became possible for HIV positive patients (5). A phase II trial of R-CHOP in 42 patients with ARL yielded a complete remission rate of 77% and an estimated two year overall survival probability of 75% (5). The authors of this trial emphasized that the response rate (76%) and overall survival at two years (70%) were consistent with the phase III GELA (Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte) trial where 399 HIV negative elderly patients were randomized to receive R-CHOP or CHOP alone as induction therapy (6). Thus, in the HAART era, response rates for HIVpos-NHL are expected to be similar to HIVneg-NHL treated with similar standard dose chemotherapy.

Currently it is unknown whether poor risk HIVpos-NHL patients who undergo high dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) experience long-term outcomes that are similar to HIVneg-NHL patients. Trials from our institution and European centers demonstrated feasibility and safety of transplant in HIVpos-NHL (7,8). The City of Hope was the United States center that pioneered the use of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for HIV positive patients. Our trial, updated in 2008 to include 23 patients who received either cyclophosphamide BCNU Etoposide (CBV) or radiation based conditioning, reported a disease free survival of 78% at two years with a median follow up of 41 months (9). Other multicenter trials have echoed the feasibility of this approach. The AIDS clinical trial group recently reported the results from a multi-institutional trial that utilized busulfan and cyclophosphamide for conditioning, and among the 27 patients enrolled, 20 went on to transplant with a six-month event free survival of 49.5% (8). However, many physicians still automatically consider HIV status to be a barrier to transplant and similarly transplant centers often exclude these patients from their protocols.

We have now reached a time where some researchers consider HIV to be a chronic illness that should be treated as any other co-morbidity. Many patients with HIV infection live for many years and no longer die of infectious causes. Nonetheless, they remain susceptible to other risks such as cardiovascular disease and malignancy. Given the greatly decreased mortality associated with HIV infection, one must question whether it is still justified to exclude HIV infected individuals from treatments that are the standard of care for HIV negative patients. Some physicians in the solid organ transplant literature have gone so far as to say, “The HIV patients should be considered no different than any other patient who may have higher transplant risks than the average patient, such as the African American, highly sensitized, diabetic or older patients.” (11,12). Randomized trials to investigate hematopoietic stem cell outcomes based on HIV status will not be possible. However, well-described retrospective studies of outcomes may corroborate this bold assertion and hopefully convince more physicians to offer transplant to HIV positive patients. To further investigate the impact of HIV infection on ASCT, a single institution case-control study of 29 HIVpos-NHL patients and 29 matched HIVneg-NHL controls was performed.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The City of Hope (COH) observational research transplant database identified a consecutive case series of 29 HIVpos-NHL patients and 29 matched HIVneg-NHL controls treated with ASCT between the years 1998 and 2007. Patients were matched on gender, age at ASCT ± 5 years, year of transplant ± 5 years, disease status at ASCT, number of prior regimens of chemotherapy, time from NHL diagnosis to ASCT, conditioning regimen and histology. In situations where more than one potential control was identified, the best matched HIVneg-NHL control was selected. The COH Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the analysis of these data. Pathology and pre-transplant staging were also reviewed at the City of Hope. International Working Group criteria (IWG) defined disease response post transplant as some patients were treated prior to implementation of revised response criteria (13).

Eligibility Criteria

The indications for ASCT included NHL in first partial remission, high-risk first remission (as defined by the international prognostic index) or relapsed disease. Standard transplant organ function criteria were used to assess physiologic suitability for ASCT. HIV positive patients were required to have a viral load <50,000copies/ml and to be free of opportunistic infections for one year prior to ASCT.

Conditioning Regimen and Supportive Care

The choice of conditioning regimen was based on institutional practice guidelines for NHL at the time. Patients were conditioned primarily with non-radiation based conditioning of either CBV (cyclophosphamide, BCNU, Etoposide) or BEAM (BCNU, Etoposide, Cytarabine, Melphalan).

Statistical Methods

Survival estimates were calculated based on the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method, 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the logit transformation and the Greenwood variance estimate (14). Patients who were alive at the time of analysis were censored at the last contact date. Overall survival (OS) was measured from transplant to death from any cause. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as time from transplant to recurrence, progression or death. The time to relapse/progression was defined as time from transplant to recurrence or progression. The cumulative incidence for relapse/progression was computed treating a non-relapse/progression death event as a competing risk. Non-relapse mortality (NRM) was measured from transplant to death from any cause other than disease relapse or disease progression. Differences between survival curves were assessed by the log-rank test. Assessment of potential baseline differences between the two groups was examined using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test for continuous variables or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The significance of patient, disease and treatment features was assessed using survival analysis and univariate Cox regression analysis (15). Univariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to model time to event endpoints (e.g., OS, DFS, relapse/progression, and NRM), as a function of the prognostic variables. The list of prognostic variables was determined from a literature review that identified factors associated with survival and/or disease relapse/recurrence in NHL patients treated with ASCT. The variables included as part of this assessment were: histopathological subtype (diffuse large B-cell vs. others), median number of prior therapies (<2, ≥2), patient age at ASCT (<44 years, ≥44 years), disease grade (intermediate vs. others), disease stage (I-II vs. III-IV), disease status at the time of ASCT (CR/PR vs. relapse/induction failure), presence of marrow involvement at diagnosis (yes, no), and HIV status at ASCT (positive, negative). Statistical significance was set at the P <0.05 level.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A consecutive case-series of 29 HIVpos-NHL patients and 29 matched HIVneg-NHL controls treated with ASCT between the years of 1998 and 2007 were included. Patient, disease, and treatment characteristics for both groups are provided in Table 1. An assessment of potential differences in disease and treatment characteristics between the two groups showed no significant ‘baseline’ differences with the exception of disease grade. A larger proportion of HIVpos-NHL patients were diagnosed with highgrade disease (n=17, 59%) when compared to the HIVneg-NHL controls (n=2, 7%). Both groups were comprised primarily of male patients (n=27, 93%), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and transplanted within the first year post NHL diagnosis. At the time of transplant the majority of patients had received a median of 2 (range: 1–4) prior regimens, were in CR/PR, and had chemo-sensitive disease. Five patients were diagnosed with HIV infection concomitant with the lymphoma diagnosis and started on antiretroviral therapy. In regards to HIV status, the median CD4 count at study entry was 153.5 (range: 25–620) and the viral load was 6500 (range: 730–32000). Twenty-two patients had an undetectable viral load at study entry. All patients in the HIV cohort were on HAART at the time of transplant, however, temporary interruption of therapy was required in 13 patients.

Table 1.

Patient, Disease, and Treatment Characteristics

| Characteristic | HIV+ NHL1 (Case) N=29 |

HIV-NHL1 (Control) N=29 |

p-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Gender | |||

| Female | 2 (7) | 2 (7) | 0.99 |

| Male | 27 (93) | 27 (93) | |

| Age at ASCT (Years) | 42 (11–68) | 48 (21–65) | 0.06 |

| Histology | |||

| Diffuse Large B-Cell | 14 (48) | 22 (76) | --- |

| Mediastinal Large B-Cell | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | |

| Marginal Zone B-Cell | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | |

| Immunoblastic Large B-cell | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | |

| Burkitt Lymphoma | 11 (38) | 0 (0) | |

| Follicular Lymphoma | 0 (0) | 4 (14) | |

| Anaplastic Large Cell | 2 (7) | 1 (3) | |

| Stage at Diagnosis | |||

| I | 1 (3) | 4 (14) | 0.41 |

| II | 1 (3) | 2 (7) | |

| III | 8 (28) | 6 (21) | |

| IV | 19 (66) | 17 (58) | |

| Bone Marrow Involvement at Diagnosis |

|||

| Yes | 8 (28) | 9 (31) | 0.74 (Yes vs. |

| No | 18 (62) | 18 (62) | No) |

| Unknown, Test Not Done | 3 (10) | 2 (7) | |

| Extranodal Disease at Diagnosis | |||

| Yes | 20 (69) | 18 (62) | 0.56 (Yes vs. |

| No | 8 (28) | 11 (38) | No) |

| Test Not Done | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Time from Diagnosis to ASCT (Months) |

11.7 (0.2– 115.3) |

12.6 (5.8– 205.6) |

0.25 |

| Number of Prior Regimens | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) | 0.33 |

| Chemo Sensitivity | |||

| Yes | 23 (79) | 27 (93) | 0.10 |

| No | 6 (21) | 2 (7) | |

| Disease Status at ASCT | |||

| CR/PR | 20 (69) | 20 (69) | 0.61 |

| Relapse | 7 (24) | 6 (21) | |

| IF | 2 (7) | 3 (10) | |

| ASCT Conditioning Regimen | |||

| FTBI/VP16/CY | 4 (14) | 4 (14) | 0.32 |

| BCNU/VP16/CY | 25 (86) | 22 (76) | |

| BEAM | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | |

Reported as number of patients (percent) or median (range)

McNemar’s X2 test applied for categorical data; Wilcoxon Rank Sum test applied for continuous data

Outcomes

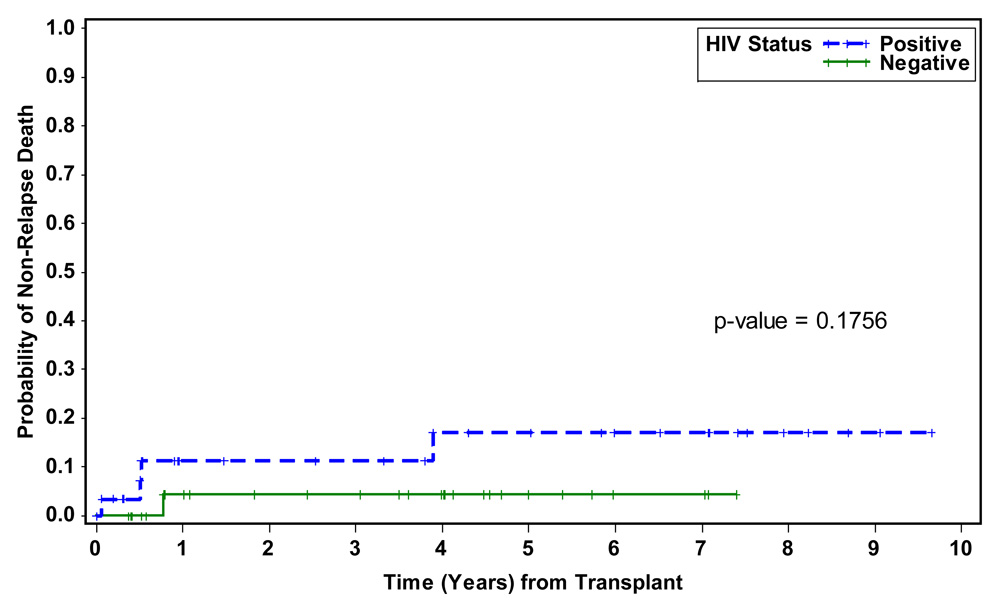

At the time of analysis the median follow-up for HIVpos-NHL patients was 62.4 months (range: 0.7–123.3) and 48.4 months (range: 4.4–101.6) for the HIVneg-NHL controls. The median number of days to neutrophil engraftment (ANC ≥ 500) was similar for both groups: 10 days (range: 5–19) for HIVpos-NHL patients and 11 days (range: 9–35) for HIVneg-NHL controls. Non-relapse mortality calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method were also similar, 11% in the HIV positive patients and 4% in the controls at one year (Figure 4). Although infectious complications did differ between the two groups, with more opportunistic infections seen in the HIV positive patients, this did not impact survival (Table 2). The major difference in infections was incidence of opportunistic viral infections in the HIV positive group with three cases of CMV viremia and one case of adenovirus viremia and one case of varicella infection. HIV viral load was monitored post transplant, at three months the median viral load was 1600 (range: 52–149,680). Causes of death in the HIV positive patients were primarily due to relapsed lymphoma. Disease free and overall survival were not significantly different between the groups (see figure(s) 1 and 2). There were eight deaths in the HIV positive group, four from NHL, one from therapy related acute leukemia, one from congestive heart failure, one from sepsis and one outside death of unknown cause. In the HIV negative group there were ten deaths, eight from disease progression or relapse, one from therapy related acute leukemia and one from interstitial pneumonitis.

Figure 4.

Probabiliy of non-Relapse Death

Table 2.

Summary of Outcomes Post ASCT

| Outcome | HIV+ NHL1 (Case) N=29 |

HIV- NHL1 (Control) N=29 |

|---|---|---|

| Engraftment | ||

| Days to reach ANC ≥ 500 | 10 (5–19) | 11 (9–35) |

| Total number of pts experiencing infection within 100 days: Grade ≥ 3* |

16 | 10 |

| Total number of infections | 28 | 14 |

| Bacterial | 17 | 11 |

| Fungal | 0 | 1 |

| Viral | 1 | 1 |

| OI (cmv, vzv) | 4 | 0 |

| Unclassified** | 6 | 1 |

| Progression/Relapse | ||

| Yes | 6 (21) | 15 (52) |

| No | 23 (79) | 14 (48) |

| Number of Death Events | ||

| Alive | 21 (72) | 19 (66) |

| Dead | 8 (28) | 10 (34) |

| Causes of Death | ||

| Disease Progression/Relapse | 4 | 8 |

| Other | ||

| Interstitial Pneumonitis | 0 | 1 |

| Sepsis | 1 | 0 |

| Secondary Malignancy, AML | 1 | 1 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1 | 0 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 |

Reported as number of patients (percent) or median (range)

All infections ≥grade 3 are included regardless of attribution.

Unclassified= no organism could be isolated

Figure 1.

Probability of Overall Survival by HIV Status

Figure 2.

Probability of Disease Free Survival by HIV Status

We further examined the impact of HIV status on survival and relapse/progression by univariate Cox regression analysis. The results of this analysis showed that HIVpos-NHL patients were not at increased risk for death or relapse/progression post ASCT when compared to HIVneg-NHL patients (Table 3). Of the factors tested, only disease status at transplant consistently emerged as predictive of outcome.

Table 3.

Results of Univariate Analysis

| Overall Survival | Disease Free Survival | Relapse/Progression | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Value | N | # of events |

Hazard Rate Ratio (95% CI) |

p- value |

# of events |

Hazard Rate Ratio (95% CI) |

p- value |

# of events |

Hazard Rate Ratio (95% CI) |

p- value |

| Age at HCT | 0: < 44 | 58 | 16 | Baseline |

0.35 | 20 | Baseline |

0.68 | 16 | Baseline |

0.63 |

| 1: ≥ 44 | 1.62 (0.59– 4.46) |

1.20 (0.50– 2.91) |

1.27 (0.47– 3.41) |

||||||||

| Histology at HCT |

0: Others | 58 | 16 | Baseline |

0.04 | 20 | Baseline |

0.06 | 16 | Baseline |

0.19 |

| 1: DLBCL | 4.64 (1.05– 20.42) |

2.82 (0.94– 8.44) |

2.13 (0.69– 6.61) |

||||||||

| NHL Grade | 0: Others |

58 | 16 | Baseline |

0.12 | 20 | Baseline |

0.17 | 16 | Baseline |

0.22 |

| 1: Intermediate |

2.73 (0.78– 9.58) |

2.04 (0.74– 5.61) |

2.04 (0.66– 6.32) |

||||||||

| Stage at Diagnosis |

0: I - II |

58 | 16 | Baseline |

0.84 | 20 | Baseline |

0.61 | 16 | Baseline |

0.86 |

| 1: III - IV | 1.17 (0.26– 5.14) |

1.46 (0.34– 6.31) |

1.15 (0.26– 5.05) |

||||||||

| Extranodal Disease at Diagnosis |

0: No |

57 | 15 | Baseline |

0.57 | 19 | Baseline |

0.64 | 15 | Baseline |

0.22 |

| 1: Yes | 0.74 (0.26– 2.08) |

0.80 (0.32– 2.04) |

0.53 (0.19– 1.46) |

||||||||

| Number of Prior Regimens |

0: < 2 |

58 | 16 | Baseline |

0.13 | 20 | Baseline |

0.30 | 16 | Baseline |

0.25 |

| 1: ≥ 2 | 4.71 (0.62– 35.69) |

1.92 (0.56– 6.57) |

2.40 (0.55– 10.58) |

||||||||

| Disease Status at HCT |

0: CR/PR |

58 | 16 | Baseline |

0.047 | 20 | Baseline |

0.01 | 16 | Baseline |

<0.01 |

| 1: RL/IF | 2.71 (1.02– 7.24) |

3.00 (1.24– 7.25) |

3.98 (1.47– 10.74) |

||||||||

| HIV Status | 0: Negative |

58 | 16 | Baseline |

0.91 | 20 | Baseline |

0.32 | 16 | Baseline |

0.12 |

| 1: Positive | 1.06 (0.40– 2.81) |

0.64 (0.26– 1.56) |

0.43 (0.15– 1.25) |

||||||||

DISCUSSION

ASCT has long been accepted as the optimal therapy for poor risk NHL. The original randomized trials (e.g., the PARMA trial) excluded patients with HIV infection, but served to position ASCT as the standard of care for relapsed NHL by demonstrating superior DFS and OS when compared with conventional salvage therapy (10). Prior to this time it was appropriate to exclude patients with HIV infection as that was before the start of effective antiretroviral therapy. At that time, pre 1996, HIV infected patients often had severe hematologic impairment and increased mortality due to infections. Post 1996 the use of HAART changed the prognosis of HIV infection (1). Therefore in this era it was appropriate to question prior paradigms. The first paradigm was that patients with HIV associated lymphomas should be treated with more gentle chemotherapy. The m-BACOD vs low dose m-BACOD trial had formed the basis for this theory. In that trial, patients treated on the standard chemotherapy dose arm had more hematologic toxicity without any difference in overall or disease free survival compared to the reduced dose arm (18). However, since this trial took place between 1991 and 1994, the patients were not on HAART. In the HAART era patients have been treated with what is considered standard of care for HIV negative NHL patients, R-CHOP. The French reported complete response rates of 77% and 2 year survival of 75% in a series of 61 patients with HIV associated NHL (5). These results are comparable to those of HIV negative patients treated with R-CHOP, and therefore, in the era of HAART, disproves the paradigm that less chemotherapy leads to more favorable outcome in the treatment of HIV NHL.

The paradigm of HIV infection limiting the feasibility and tolerability of stem cell mobilization and ASCT was also challenged in the era of HAART. Investigators from France were the first to report on the use of ASCT in a group of fourteen patients. All the patients engrafted but eight died, six from progressive NHL. Nonetheless despite these high relapse rates, this was the first study to demonstrate the feasibility of ASCT in HIV infected individuals (16). The City of Hope expanded upon this experience in a larger series of patients all with chemosensitive disease (17). This initial series also demonstrated that transplant related mortality was low in the HIV positive patient and that durable remissions from the lymphoma could be obtained. A recently published multicenter trial from twenty centers in Europe provided further corroboration (19). The trial enrolled patients from 1999 and included a total of sixty-eight patients. The non-relapse mortality (NRM) was 7.5%, mainly because of bacterial infections. The progression free survival (PFS) was 56%. The series included eight patients with chemorefractory disease, and subgroup analysis, not surprisingly found that patients not in CR or with refractory disease at the time of transplant had a poorer PFS. The Italian cooperative group on AIDS and tumors also showed a high PFS of 76% in the twenty one patients who underwent transplant. (22) The non-relapse mortality is similar to the PARMA trial of HIV negative patients undergoing ASCT, where there was a 6% toxic death rate, four patients died of infection and one patient from cardiac toxicity (10). Of the 29 patients in each cohort in our series, the number who developed infections was small: 16 in the HIV positive patients and 10 in the HIV negative group. The total number of infections is detailed in table 2, as expected several patients had more than one infection. Due to the small number of patients in each cohort, the impact of the type of infection, e.g. bacterial on mortality could not be demonstrated.

The aforementioned studies certainly are suggestive that the outcome is similar for HIV positive patients compared with their HIV negative counterparts. A multicenter case control study from Europe supports this (21). A registry based study of eighteen centers in Europe looked at fifty-three patients with HIV associated NHL and Hodgkin lymphoma who underwent autologous transplant in the era of HAART and compared them to controls matched for histology, stage at diagnosis, non age adjusted IPI (NHL pts), disease status at ASCT. Days to neutrophil engraftment were identical in both groups at eleven days. Overall survival was 61.5% for HIV positive patients and 70% for the HIV negative controls (p=NS). The main cause of death was relapse in both groups, though there was a not statistically significant difference in nonrelapse mortality in the HIV positive group due to bacterial infections.

Our study while encompassing a smaller number of patients confirms the European series and furthermore, has the advantage that it is a single institution series with the standard of care and patient selection identical for the HIV positive cases as well as the HIV negative control. The longer followup in our series allows further evaluation of the potential for late effects of HIV infection on transplant outcome. Overall survival was the same in both cohorts, which were treated identically. Interestingly, despite the inclusion of more potentially high-risk patients, those with high grade lymphomas in the HIV positive cohort, PFS was not statistically different between the groups. Somewhat akin to this, in the European case control series, the difference in confidence interval of relapse for both cohorts was not statistically significant (29% for HIV positive and 42% for HIV negative), but there was a more favorable trend in the HIV positive group. (21)

These studies, therefore, lay the groundwork for the idea that perhaps, HIV is not the ultimate arbiter to poor transplant outcome for patients with NHL. The intriguing trend towards lower relapse in the HIV positive group of patients also raises many questions about the effect of transplant on the underlying HIV infection. Perhaps transplant is also resetting the clock on the immunologic effects of HIV, either by depleting the HIV reservoir or by its alterations on the T cell reconstitution. Future studies are planned to address these issues. For example, in HIV positive patients with an undetectable viral load by conventional assays, persistent viremia as low as single copies/ml can be measured by PCR. It remains unclear whether this low level viremia is due to the death of previously infected cells or to ongoing viral replication. It is possible that high dose chemotherapy depletes the cells in the reservoir that harbored latent virus and therefore, single copy PCR levels post transplant would reflect this. Other genotypic effects may also come into play. Future correlative studies addressing the questions of viral reservoir, CCR5 status and immune reconstitution are being planned as part of the BMT CTN national study of ASCT in HIV NHL. This study will also use the completed BMT CTN trial of BEAM vs Bexxar BEAM conditioning with ASCT in HIV negative NHL as a comparator. Hopefully this coordinated effort through the transplant centers in the United States will encourage more physicians to consider transplant for their NHL patients regardless of HIV status. In 1997, 88% of transplant centers excluded patients with HIV infection from solid organ transplantation. (20). This bias is slowly changing. Our data supports that HIV infection did not lead to inferior long-term outcome post ASCT. Perhaps, we should soon challenge the final paradigm of excluding patients with well-controlled HIV from ASCT clinical trials.

Figure 3.

Cumulative Proability of Relapse/Progression

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge our transplant coordinators and transplant nurses for their dedicated care of our patients. We would also like to thank all the members of the Hematopoietic Cell Transplant team for their constant support of the program, including the clinical research associates for their protocol management and data collection support. This work was supported by the Comprehensive Cancer Center grant (P30 CA033572), Hem/HCT Program Project grant (PO1 CA030206), Lymphoma SPORE (P50 CA107399), Marcus Foundation, Tim Nesvig Lyphoma Research Fund, and the Sheryl Weisberg Lymphoma Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: There are no disclosures to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: AK, JP, and SF

Provision of study materials or patients: AK, JAZ and SF

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: AK, JP, JAZ and SF

Collection and assembly of data: AK, JP, and NT

Analysis and interpretation of data: AK, JP and SF

Drafting of the article: AK, JP, JAZ, JA and SF

REFERENCES

- 1.Palella FJ, Delaney KM, Moorman MC, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binnet F, Lewden C, May T, et al. Malignancy related causes of death in human immunodeficiency virus infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Cancer. 2004;10:317–324. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine AM. Acquired Immunodeficiency Lymphoma. Blood. 1992;80:8–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine AM, Sullivan Halley J, Pike MC, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus related lymphoma: Prognostic factors predictive of survival. Cancer. 1991;68:2466–2472. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19911201)68:11<2466::aid-cncr2820681124>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boue J, Gabarre J, Gisselbrecht G, et al. Phase II trial of CHOP plus rituximab in patients with HIV associated non Hodgkin lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:4123–4128. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Brière J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishnan A, Zaia J, Rossi J, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for AIDS related lymphoma and the potential role of HIV resistant stem cells. Blood. 108:491. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spitzer T, Ambinder R, Lee J, et al. Dose reduced busulfan, cyclophosphamide and autologous stem cell transplantation for human immunodeficiency virus associated lymphoma: AIDS malignancy consortium study 020. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2000;4:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan A, Zaia J, Alvarnas J, et al. The 11th Annual International Conference on AIDS. National Institutes of Health. 2008 Abstract 41, October 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Philip T, Giglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy sensitive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;333:1540–1545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Persad G, Little R, Grady C. Including persons with HIV infection in cancer clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:1027–1032. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qiu J, Terasaki PI, Waki K, et al. HIV positive renal recipients can achieve survival rates similar to those of HIV negative patients. Transplantation. 2006;81:1658–1661. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000226074.97314.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17:1244–1253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox DR. Regression model and life tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabarre J, Choquet S, Azar N, et al. High dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant for HIV associated lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1996;18:1195–1197. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishnan A, Molina A, Zaia J, et al. Durable remissions with autologous stem cell transplantation for high risk HIV associated lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:874–878. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan LD, Strauss D, Testa M, et al. Low dose compared with standard dose m-BACOD chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336:1641–1648. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706053362304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balsalobre P, Diez-Martin J, Re A, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with HIV related lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:2192–2198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halpern SD, Ubel PA, Caplan AL. Solid organ transplantation in HIV infected patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347:284–287. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb020632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diez-Martin J, Balsalobre P, Re A, et al. Comparable survival between HIV positive and HIV negative non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphoma patients undergoing autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;113:6011–6014. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Re A, Michieli M, Casari B, et al. High dose therapy and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for salvage treatment for AIDS related lymphoma:long-term results of the Iltalian Cooperative Group on AIDS and Tumors study with analysis of prognostic factors. Blood. 2009;114:1306–1313. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-202762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]