Abstract

Objectives To estimate survival after a diagnosis of dementia in primary care, compared with people without dementia, and to determine incidence of dementia.

Design Cohort study using data from The Health Improvement Network (THIN), a primary care database.

Setting 353 general practices in the United Kingdom providing data to THIN.

Participants All adults aged 60 years or over with a first ever code for dementia from 1990 to 2007 (n=22 529); random sample of five participants without dementia for every participant with dementia matched on practice and time period (n=112 645).

Main outcome measures Median survival by age and sex; mortality rates; incidence of dementia by age, sex, and deprivation.

Results The median survival of people with dementia diagnosed at age 60-69 was 6.7 (interquartile range 3.1-10.8) years, falling to 1.9 (0.7-3.6) years for those diagnosed at age 90 or over. Adjusted mortality rates were highest in the first year after diagnosis (relative risk 3.68, 95% confidence interval 3.44 to 3.94). This dropped to 2.49 (2.29 to 2.71) in the second year. The incidence of recorded dementia remained stable over time (3-4/1000 person years at risk). The incidence was higher in women and in younger age groups (60-79 years) living in deprived areas.

Conclusions Median survival was much lower than in screened populations. These clinically relevant estimates can assist patients and carers, clinicians, and policy makers when planning support for this population. The high risk of death in the first year after diagnosis may reflect diagnoses made at times of crisis or late in the disease trajectory. Late recording of diagnoses of dementia in primary care may result in missed opportunities for potential early interventions.

Introduction

Dementia is a global condition, and 80 million people worldwide are predicted to be affected by 2040.1 Dementia syndromes have a huge impact on people with the illness, and their families and carers, with substantial health, societal, and economic consequences.2 3 4 Among people with dementia, men, older people, and those with pre-existing comorbid conditions have decreased life expectancy and survival in community studies.5 6 7 8

Family doctors provide most medical care for people with dementia.9 The incidence of dementia in primary care is expected to rise as the demographic profile of the population shifts towards older people. The recording of dementia in the clinical records in primary care requires both recognition of the problem by the clinician and the entry of a diagnosis on the medical record. Most estimates of incidence and survival are based on studies in the community, with active case finding through the use of structured screening instruments for dementia.5 6 7 8 A recent such study reported an overall median survival of 4.1 years for men and 4.6 years for women.8 The mortality of people with dementia in such community studies has been found to be higher than that of people without the condition.6 10 11 12 These estimates, however, will differ from those in populations derived from people known to their family doctors, where a diagnosis is recorded only after clinical presentation and recognition of symptoms.

Diagnosis of dementia often occurs late. The UK’s national dementia strategy suggests that the United Kingdom is in the bottom third of performance in Europe in terms of diagnosis and treatment.13 No large primary care studies on incidence and survival from the point of clinical diagnosis have been done to confirm this perception. Such studies may offer a more accurate estimate of the extent of the workload generated by this population. Primary care clinical databases afford an unrivalled opportunity to examine the outcomes of large numbers of people in clinical settings and provide “real life” estimates of survival in this setting. Survival from the point of recognition of dementia by the clinician may also be of greater relevance to patients, carers, health professionals, and planners than are survival data based on screened populations. The objectives of this study were to determine incidences of recorded dementia in primary care between 1997 and 2007 and survival from the point of recorded diagnosis of dementia in comparison with people without dementia in the period 1990-2007.

Methods

In this cohort study, we examined data from general practices in the UK providing data to The Health Improvement Network (THIN) during the period January 1990 to August 2007. We used only practices that met standards for acceptable levels of data recording. For the survival study, we used data from practices that met the criteria for acceptable standards of mortality reporting.14

Data source

The Health Improvement Network (www.epic-uk.org/thin.htm) electronic recording scheme is one of the largest sources of continuous primary care data on patients’ consultations and prescribing in the UK. It is a clinical database in which every consultation in participating practices is recorded and contains the electronic clinical records of more than 5 million patients. It has been widely used for epidemiological studies.15 16 Anonymised patients’ data are collected from 358 participating practices that are broadly representative of UK general practices in terms of patients’ age and sex, practice size, and geographical distribution.17 General practitioners record medical diagnoses and symptoms by using Read codes, a hierarchical recording system used to record clinical summary information. The age, sex, medical diagnosis and symptom records, health promotion activity, referrals to secondary care, prescriptions, and fifths of deprivation score are recorded for each registered person.

Participants

“Exposed” participants—We included all adults aged 60 years or over with a first ever code for dementia (as defined below) during the period January 1990 to August 2007.

“Unexposed” participants—We selected a random sample of five people without dementia, registered at the same general practice at the time of diagnosis, for every person with dementia aged 60 years and over.

Exclusions—We excluded people with a history of dementia (before study entry) or a dementia syndrome related to HIV, Pick’s disease, Huntingdon’s disease, or Parkinson’s disease. We excluded patients’ follow-up time and diagnoses in the first six months after registration with a practice. These entries could represent retrospective recording of medical history rather than a true incident recording of dementia.18 We also excluded patients with less than six months of data from registration with their general practitioner.

Measurements

The study team developed lists of Read codes to identify recorded diagnoses of dementia. These included people with codes for non-specific dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia but did not include codes for memory symptoms or cognitive impairment. For the purpose of determining incidence, we examined age by four age bands (60-69, 70-79, 80-89, and 90 and above). We examined deprivation by using fifths of Townsend score from 1 (least deprived) to 5 (most deprived). The Townsend deprivation score is a combined measure of owner occupation, car ownership, overcrowding, and unemployment based on a person’s postcode and linkage to population census data for 2001 for approximately 150 households in that postal area.19 We also collected information on smoking; heavy alcohol consumption; and history of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, and high cholesterol.

Analysis

We used Stata version 10 for statistical analyses. To analyse incidence, we defined cases by using the Read codes for dementia as described above. We calculated person years at risk contributed to the age groups by people registered in the THIN database between 1997 and 2007. People started contributing person years at risk six months after registration and stopped contributing at the earliest of study end date, date of death, date transferred out of the practice, date of diagnosis of dementia, or three years after their last consultation. We calculated the incidence of dementia within age groups for men and women and for fifths of deprivation.

We used the Kaplan-Meier estimator to estimate the survival function for the dementia cohort and the comparator cohort without dementia, matched on general practice and time of diagnosis for the period 1990-2007. We categorised age at diagnosis into five year age bands and estimated the survival function separately for people from each of these age bands. We censored people if they were transferred out of the practice, had not consulted in three years, or were alive at the end of the study period.

We used a conditional Poisson regression model to compare the death rate of people with and without dementia. We estimated rate ratios adjusted for age and sex separately for each year after diagnosis. In a secondary analysis, we also adjusted the rate ratios for comorbidities (smoking, heavy alcohol consumption, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, and high cholesterol).

Results

Incidence

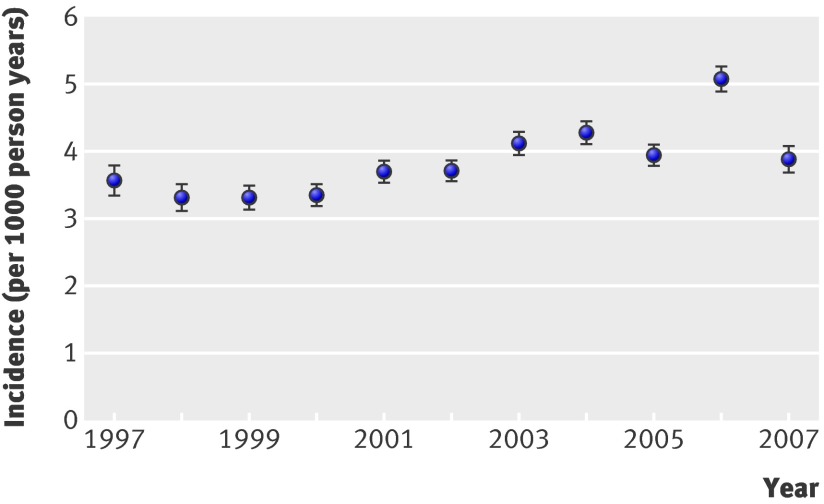

Three hundred and fifty-three practices met the criteria for acceptable data recording between January 1997 and August 2007. In total, 20 409 people aged 60 years and over had a diagnosis of dementia recorded in the study period. The incidence of recorded dementia remained relatively stable over time at between 3 and 4 per 1000 person years at risk (fig 1); the exception was 2006, when the incidence was significantly higher at 5/1000 person years at risk.

Fig 1 Incidence of dementia by year from 1997 to 2007

The incidence of recorded dementia was more than 15 times higher in people aged over 90 compared with the 60-69 year age group. The incidence was greater in women than men across all age groups (table 1). Greater deprivation, compared with lower deprivation, was associated with a higher rate of recorded dementia in the younger age groups (60-69 and 70-79 years), but this became less marked in the older age groups (table 2).

Table 1.

Incidence of dementia by age and sex, 1997-2007

| Age band (years) | Women | Men | Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Person years at risk | Incidence* (95% CI) | No | Person years at risk | Incidence* (95% CI) | |||

| 60-69 | 600 | 1 122 402 | 0.53 (0.49 to 0.59) | 527 | 1 086 063 | 0.49 (0.44 to 0.53) | 1.10 (0.98 to 1.24) | |

| 70-79 | 3515 | 936 166 | 3.75 (3.63 to 3.88) | 2179 | 774 927 | 2.81 (2.69 to 2.93) | 1.34 (1.27 to 1.41) | |

| 80-89 | 7193 | 608 358 | 11.82 (11.55 to 12.10) | 3120 | 366 622 | 8.51 (8.21 to 8.81) | 1.39 (1.33 to 1.45) | |

| ≥90 | 2603 | 231 523 | 11.24 (10.81 to 11.67) | 672 | 89 804 | 7.48 (6.92 to 8.05) | 1.50 (1.38 to 1.64) | |

*Incidence of dementia per 1000 person years at risk.

Table 2.

Incidence of dementia by deprivation fifth

| Deprivation fifth | Age band (years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60-69 | 70-79 | 80-89 | ≥90 | |

| 1 (low) | 0.42 (0.36 to 0.47) | 2.87 (2.70 to 3.04) | 10.74 (10.27 to 11.21) | 11.58 (10.68 to 12.48) |

| 2 | 0.41 (0.36 to 0.47) | 3.01 (2.83 to 3.19) | 10.28 (9.83 to 10.73) | 11.71 (10.84 to 12.59) |

| 3 | 0.55 (0.48 to 0.63) | 3.32 (3.12 to 3.52) | 10.82 (10.36 to 11.29) | 11.32 (10.47 to 12.18) |

| 4 | 0.61 (0.53 to 0.69) | 3.97 (3.74 to 4.20) | 11.58 (11.08 to 12.08) | 12.35 (11.39 to 13.30) |

| 5 (high) | 0.70 (0.59 to 0.81) | 4.17 (3.88 to 4.46) | 11.87 (11.26 to 12.48) | 11.48 (10.35 to 12.60) |

| Rate ratio* | 1.68 (1.40 to 2.03) | 1.45 (1.34 to 1.58) | 1.11 (1.04 to 1.18) | 0.99 (0.89 to 1.10) |

*Highest versus lowest fifth of deprivation.

Survival

Three hundred and forty-nine practices met the criteria for acceptable data and mortality recording between January 1990 and August 2007. These practices had 22 529 people aged 60 years and over with a recorded diagnosis of dementia (table 3), with 40 424 person years of follow-up. Two thirds of people with dementia were female (67.9%), and the mean age was 82.2 (SD 7.4) years. Most people with dementia were coded with a non-specific dementia code (n=14 485; 64.3%); about a fifth had been given a code of Alzheimer’s disease (4674; 20.7%), and 15% (3370) had a code of vascular dementia.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics for participants with and without dementia in survival study (1990-2007). Values are numbers (percentages)

| Characteristic | Dementia (n=22 529) | Non-dementia (n=112 645) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 15 305 (67.9) | 62 830 (55.8) |

| Age (years): | ||

| 60-69 | 1 397 (6.2) | 52 733 (46.8) |

| 70-79 | 6 725 (29.9) | 37 545 (33.3) |

| 80-89 | 11 249 (49.9) | 18 723 (16.6) |

| ≥90 | 3 158 (14.0) | 3 644 (3.2) |

| Deprivation fifth: | ||

| 1 (least deprived) | 4 318 (19.2) | 25 040 (22.2) |

| 2 | 4 275 (19.0) | 23 825 (21.2) |

| 3 | 4 438 (19.7) | 21 195 (18.8) |

| 4 | 4 386 (19.5) | 19 685 (17.5) |

| 5 (most deprived) | 3 113 (13.8) | 13 891 (12.3) |

| Not recorded | 1 999 (8.9) | 9 009 (8.0) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 5 047 (22.4) | 23 251 (20.6) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6 605 (29.3) | 14 927 (13.3) |

| Diabetes | 3 136 (13.9) | 16 300 (14.5) |

| Hypertension | 8 706 (38.6) | 50 148 (44.5) |

| High cholesterol | 2 513 (11.2) | 23 907 (21.2) |

| Smoking status: | ||

| Smoker/ex-smoker | 7 121 (31.6) | 50 330 (44.7) |

| Non-smoker | 12 518 (55.6) | 55 850 (49.6) |

| Not recorded | 2 890 (12.8) | 6 465 (5.7) |

| Alcohol dependency | 946 (4.2) | 6 395 (5.7) |

The matched comparison group contained 112 645 people aged 60 years and over without dementia, with 432 307 person years of follow-up. This group was younger (mean age 72.2 (SD 8.6) years) and consequently had a longer median follow-up time (3.1 (interquartile range 1.4-5.6) years) than did people with dementia (1.3 (0.5-2.7) years). In the dementia group, 41.6% (n=9372) had died compared with 17.5% (n=19 713) in the non-dementia group. More than a quarter of people with dementia transferred out of the practices (27.5%; n=6195) compared with 10.2% (n=11 490) of people without dementia.

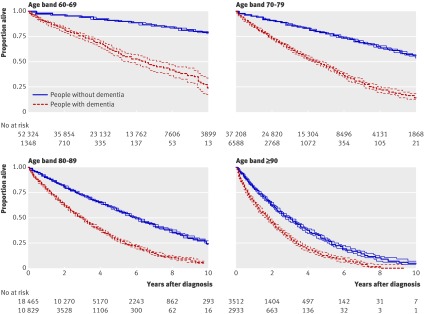

The median survival of people with a diagnosis of dementia was associated with age at first recorded diagnosis. The median survival for people aged 60-69 years at diagnosis was 6.7 (interquartile range 3.1-10.8) years, falling to 1.9 (0.7-3.6) years in those aged 90 years and over (fig 2). The five year survival ranged from just over 50% in 60-69 year olds to 25% in 80-89 years olds.

Fig 2 Kaplan-Meier survival curves for people with and without dementia

Relative mortality—The mortality rate was more than three times greater in patients with dementia than in those without dementia in the first year after the diagnosis was recorded (relative risk 3.76, 95% confidence interval 3.57 to 3.97), when adjusted for age and sex (table 4). The rate fell in subsequent years to about two and half times greater than that of people without dementia. Adjustment for comorbidities, deprivation, smoking, and alcohol had little effect on the rate ratios. The adjusted relative risk of dying remained more than three and a half times higher in the first year after dementia was diagnosed (3.68, 3.44 to 3.94).

Table 4.

Mortality rate ratios for participants with dementia compared with those without dementia

| Year of follow-up after diagnosis | Rate ratio* (95% CI) | Rate ratio† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| First | 3.76 (3.57 to 3.97) | 3.68 (3.44 to 3.94) |

| Second | 2.50 (2.33 to 2.68) | 2.49 (2.29 to 2.71) |

| Third | 2.43 (2.22 to 2.66) | 2.37 (2.13 to 2.63) |

| Fourth | 2.54 (2.27 to 2.85) | 2.48 (2.17 to 2.84) |

| Fifth | 2.62 (2.25 to 3.05) | 2.42 (2.02 to 2.90) |

| Sixth | 2.55 (2.08 to 3.12) | 2.34 (1.84 to 2.97) |

*Adjusted for age and sex.

†Adjusted for age, sex, deprivation, smoking, alcohol, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and high cholesterol.

Discussion

The incidence of recorded dementia in a UK general practice cohort has remained fairly static over the past decade at between 3 and 4 per 1000 person years at risk. This is against a background of efforts to improve awareness of early diagnosis of dementia in primary care, including the use of financial incentives to establish dementia registers in general practice. Incidences were higher in women and older people, which is consistent with other studies. The incidence was also higher in people aged 60-79 from the most deprived group compared with those from the least deprived group, but this finding was less marked in older age groups. The median survival of people with dementia decreased with age. Mortality rates were more than three times higher in people with dementia than in those without dementia in the first year after diagnosis and more than twice as high from the second to the sixth year after diagnosis.

Comparison with other studies

Pooled incidence data from four population based European studies of people aged 65 years and older found that the incidence of dementia in women increased with age from 2.9/1000 person years at risk in the 65-69 age group to 35.4/1000 person years at risk in those aged 80-84.20 The overall incidence of dementia in the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing study in the UK reported rates of 6.3 and 31.2/1000 person years at risk in women in the corresponding age groups.21 The incidences for women in our study were 0.5 and 11.8 for the 60-69 and 80-89 year age groups, illustrating the lower level of recognition and recording of dementia in primary care. The slight increase in incidence in 2006 could be explained by the introduction of incentive payments for general practitioners in the UK to record dementia on practice registers as part of the quality and outcomes framework.22 UK population projections suggest that increases in the number of people with dementia in the community are likely to be more striking in the forthcoming years than during in our study period.23

Timely diagnosis for people with dementia can facilitate appropriate support and assist family doctors to organise systematic management. We found much lower incidences than those reported from the community, suggesting that general practitioners’ recognition of dementia has remained low and has not changed over time. Evidence suggests that dementia is under-diagnosed in an estimated 50% of primary care patients over the age of 65 and that diagnosis is related to severity.24 25 Our results are consistent with primary care studies that show a lack of skills in making a diagnosis of dementia and sharing this with patients.26 This may explain the under-recording of dementia. Low levels of recording may also reflect a reluctance to give patients a label of dementia when the perception is of minimally effective available treatment. These findings also question the effectiveness of educational efforts to improve the recognition of dementia in primary care in the decade since the introduction of cholinesterase inhibitors. This underlines the emphasis on improving recognition of dementia, as proposed in the UK’s recently published national dementia strategy.12

Median survival in our study was lower than in studies of screened populations, but the effects of age and sex on survival are consistent. Lower survival in our study is probably explained by the fact that our sample was identified at a later stage of their illness. Our study is likely to be identifying people further along the dementia trajectory, where symptoms or functioning are potentially affecting the patients, their carers, or both. A case-control study reviewed 319 general practice records of people with dementia and found differences between cases and controls in terms of cognitive symptoms up to four years before diagnosis.27 Xie and colleagues examined 438 people with dementia from a screened population in the UK.8 They found higher median survival in all age groups than we saw in our study (65-69 age group 10.7 v 6.9 years; ≥90 age group 3.8 v 1.9 years). This and other studies found higher median survival in samples identified through active case finding in the community.10 An alternative explanation for reduced survival might be that diagnoses of dementia are entered more often at times of crisis, such as after an admission to hospital or comorbid infection or when cognitive function is rapidly deteriorating.

Our study found a higher relative mortality rate in the first year after diagnosis (relative risk 3.68). This may be explained by more diagnostic entries being made in the primary care record at a time of crisis, inter-current illness, hospital admission, or previous admission to an institution. Evidence exists of higher short term mortality in people with dementia after acute medical admission.28 More than twice the number of people with dementia than without dementia transferred out of practices. This may be due to the severity of the illness necessitating a move closer to carers or family or into nursing or residential homes. These people could not be followed up. If the group that transferred out was at greater risk of dying, our study may have overestimated survival. Knowing where in the disease trajectory diagnoses are being made is important. Previous studies with screened populations have also reported lower relative survival of people with dementia compared with populations without dementia.5 6 10 12

Strengths and limitations

This study examined the incidence of recorded dementia and survival in a large cohort of people seen in UK primary care. It included data from more than 22 000 new episodes of dementia recorded in routine primary care settings. We were able to assess survival from the point of recording a clinical diagnosis of dementia and compare it against a group of more than 100 000 people without dementia. With such a large sample, we can provide accurate estimates of survival in this setting. Most previous research on incidence of and survival with dementia has been done on smaller community samples, in which people were actively screened for dementia.

Our data were based on recorded dementia in general practice records. Such data depend not only on the underlying incidence in the community but also on patients presenting to family doctors and the doctors recognising dementia and then entering it in the electronic records. People with suspected dementia or with symptoms of dementia and no diagnosis would not have been included in our sample, and our results would not apply to these groups. Validation work on recording of dementia in UK primary care databases found that most (83%) of the diagnoses made by general practitioners were confirmed,29 and evidence indicates that chronic and important medical diagnoses entered in electronic records are likely to be accurate,30 31 including mental health diagnoses.32 We know from previous work that dementia tends to be under-recorded in general practice records and that general practitioners believe that they are not skilled or confident enough to make a diagnosis alone and seek specialist advice first.24 25 26 33 We would therefore anticipate that the diagnosis of dementia in general practice records has low sensitivity but high specificity. Death recording in THIN has been shown to be valid.30 Data from the electronic records do not provide a measure of the severity of dementia, which is known to influence survival. Moreover, most codes entered were non-specific and did not allow for differentiation of subtypes. We were therefore unable to assess the effect of underlying pathology (such as Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia) on survival. General practitioners may use uncoded free text options in the electronic records. Such text may include entries on dementia but would not have been identified in our search, resulting in an underestimate of the incidence. Adjustment for comorbidities produced little effect on the risk of death. This may be explained by under-recording of certain comorbidities in people with dementia, as they may be less likely to be investigated than other people with chronic diseases. For example, in our study, people with dementia were more likely to be diagnosed as having cerebrovascular disease but less likely to be recorded as having high cholesterol. However, life expectancy among people with dementia may be predominantly determined by dementia rather than by comorbidities. Although we had large numbers in the survival study, smaller numbers were available for long term follow-up.

Implications

Our study reports on people who were identified as having dementia by their general practitioners and who had this entered in their electronic record. No previous research reporting on this population has been published. Our findings contrast with data from existing cohorts that tend to relate to survival from early in the disease trajectory. This is important information for both practitioners and commissioners in the planning of health and social care, including palliative care services.

Our study supports the view that under-recognition of dementia syndromes persists in primary care, and that greater engagement of primary care in earlier and better detection of dementia is needed. In addition, we found that general practitioners often record the diagnosis of dementia in a non-specific way, not differentiating between Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. This is an important distinction that may affect management, including the use of anticholinesterase inhibitors, and should be covered in educational initiatives or through incentives. The point of primary care recording of a diagnosis is likely to be the start of a period in which greater demands are made on the primary and secondary healthcare teams and on social care. Further work is needed to explore factors underlying the decision of general practitioners to record a diagnosis of dementia and enter it on a dementia register, as well as why the mortality rates are higher in the first year after formal recording of a diagnosis. The information from this study may assist clinicians in providing information to patients and carers on median survival times at the point of diagnosis in primary care and may also aid policy makers and providers in planning services. These findings could assist future work on estimating workload and costs related to this period from clinical diagnosis onwards and inform modelling of the effect of dementia on health and social care services.

What is already known on this topic

People with dementia have a lower life expectancy than do people without dementia

Family doctors provide most medical care for people with dementia, but no survival estimates relevant to primary care are available

What this study adds

Survival after a clinical diagnosis of dementia is much lower than in screened populations

Mortality rates are more than three times higher in people with dementia than in those without dementia in the first year after diagnosis

Contributors: GR, KW, IP, IN, and SI conceived the study and obtained funding. All authors were involved in the design of the study and data interpretation. CB analysed the data, and GR drafted the article. All authors participated in revising it and approved the final version. GR is the guarantor.

Funding: The Research Department of Primary Care and Population Health, University College London (UCL), holds a license to analyse data from THIN. This study was funded by the North Central London Research Consortium and sponsored by UCL. These sources were not involved in the analysis, interpretation, or decision to submit for publication. KW and IP were supported by a special training fellowship in health services research from the Medical Research Council (UK). This sponsor had no involvement in the analysis, interpretation, or decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The study was given a favourable opinion by the Cambridge 4 Research Ethics Committee (07/MRE05/30).

Data sharing: Lists of Read codes used are available from the corresponding author at gr@gprf.mrc.ac.uk.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c3584

References

- 1.Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet 2005;366:2112-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowin A, Knapp M, McCrone P. Alzheimer’s disease in the UK: comparative evidence on cost of illness and volume of health services research funding. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:1143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comas-Herrera A, Wittenberg R, Pickard L, Knapp M. Cognitive impairment in older people: future demand for long-term care services and the associated costs. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;22:1037-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wimo A, Winblad B, Jönsson L. An estimate of the total worldwide societal costs of dementia in 2005. Alzheimers Dement 2007;3:81-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mölsä PK, Marttila RJ, Rinne U. Long-term survival and predictors of mortality in Alzheimer’s disease and multi-infarct dementia. Acta Neurol Scand 1995;91:159-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aguer-Torres H, Fratiglioni L, Guo Z, Viitanen M, Winbald B. Mortality from dementia in advanced age: a 5 year follow-up study of incident dementia cases. J Clin Epidemiol 1999;52:737-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfson C, Wolfson D, Asgharian M, M’Lan CE, Ostbye T, Rockwood K, et al. A reevaluation of the duration of survival after the onset of dementia. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie J, Brayne C, Matthews F, Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study Collaborators. Survival times in people with dementia: analysis for a population based cohort study with 14 year follow-up. BMJ 2008;336:258-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villars H, Oustric S, Andrieu S, Baeyens JP, Bernabei R, Brodaty H, et al. The primary care physician and Alzheimer’s disease: an international position paper. J Nutr Health Aging 2010;14:110-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knopman D, Rocca W, Cha R, Edland S, Kokmen E. Survival study of vascular dementia in Rochester, Minnesota. Arch Neurol 2003;60:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larson E, Shadlen M, Wang L, McCormick C, Bowen J, Teri L, et al. Survival after initial diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzpatrick A, Kuller L, Lopez O, Kawas C, Jagust W. Survival following dementia onset: Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci 2005;229:43-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health. Living well with dementia: a national dementia strategy. DH, 2009.

- 14.Maguire A, Blak B, Thompson M. The importance of defining periods of complete mortality reporting for research using automated data from primary care. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:76-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keenan HT, Hall G, Marshall SW. Early head injury and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rait G, Walters K, Griffin M, Buszewicz M, Petersen I, Nazareth I. Recent trends in the incidence of recorded depression in primary care. Br J Psychiatry 2009;195:520-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bourke A, Dattani H, Robinson M. Feasibility study and methodology to create a quality evaluated database of primary care data. Inform Prim Care 2004;12:171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis JD, Bilker WB, Weinstein RB, Strom BL. The relationship between time since registration and measured incidence rates in the general practice research database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005;14:443-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office for National Statistics. Census 2001. www.statistics.gov.uk/census2001/census2001.asp.

- 20.Anderson K, Launer LJ, Dewey ME, Letenneur L, Ott A, Copeland JR, et al. Gender differences in the incidence of AD and vascular dementia: the EURODEM studies. Neurology 1999;53:1992-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews F, Brayne C, Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study Investigators. The incidence of dementia in England and Wales: findings from the five identical sites of the MRC CFA study. PLoS Med 2005;2:e193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lester H, Sharp D, Hobbs FDR, Lakhani M. The quality and outcomes framework of the GMS contract: a quiet evolution for 2006. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:244-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Office for National Statistics. National population projections: 2006-based. ONS, 2008.

- 24.Boustani M, Peterson B, Hanson L, Harris R, Lohr K. Screening for dementia in primary care: a summary of the evidence for the US preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:927-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopponen M, Raiha I, Isoaho R, Vahlberg T, Kivela SL. Diagnosing cognitive impairment and dementia in primary health care—a more active approach is needed. Age Ageing 2003;32:606-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iliffe S, Wilcock J, Haworth D. Obstacles to shared care for patients with dementia: a qualitative study. Fam Pract 2006;23:353-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bamford C, Eccles M, Steen N, Robinson L. Can primary care record review facilitate earlier diagnosis of dementia? Fam Pract 2007;24:108-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samson E, Blanchard M, Jones L, Tookman A, King M. Dementia in the acute hospital: prospective cohort study of prevalence and mortality. B J Psych 2009;195:61-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunn N, Mullee M, Perry VH, Holmes C. Association between dementia and infectious disease: evidence from a case-control study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2005;19:91-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall GC. Validation of death and suicide recording on the THIN UK primary care database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:120-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis JD, Schinnar R, Bilker WB, Wang X, Strom BL. Validation studies of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database for pharmacoepidemiology research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:393-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nazareth I, King M, Haines A, Rangel L, Myers S. Accuracy of diagnosis of psychosis on general practice computer system. BMJ 1993;307:32-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, Wilcock J, Bryans M, Levin E, et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, confidence and attitudes in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Age Ageing 2004;33:461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]