Abstract

Background

There are few validated instruments measuring parental beliefs about parent–child feeding relations and child compliance during meals.

Objective

To test the validity of the Feeding Demands Questionnaire, a parent-report instrument designed to measure parents’ beliefs about how their child should eat.

Methods

Participants were 85 mothers of 3- to 7-year-old same-sex twin pairs or sibling pairs, and their children. Mothers completed the eight-item Feeding Demands Questionnaire and the Child Feeding Questionnaire, plus measures of depression and fear of fat.

Statistical analyses

Psychometric evaluations of the Feeding Demands Questionnaire included principal components analysis, Cronbach’s α for internal consistency, tests for convergent and discriminant validities, and Flesh-Kincaid for readability.

Results

The Feeding Demands Questionnaire had three underlying factors: anger/frustration, food amount demandingness, and food type demandingness, for which subscales were computed. The Feeding Demands Questionnaire showed acceptable internal consistency (α ranging from .70 to .86) and was written at the 4.8th grade level. Mothers reporting greater anger/frustration during feeding were more likely to pressure their children to eat, while those reporting greater demands about the type of foods their children eat were more likely to monitor child fat intake. Mothers reporting greater demands about the amount of food their children eat were more likely to restrict eating, pressure children to eat, and monitor their fat intake.

Conclusions

The Feeding Demands Questionnaire appears valid for assessing maternal beliefs that children should comply with rules for eating and frustration during feeding. Different demand beliefs can underlie different feeding practices.

There is interest in parental feeding styles and attitudes as they relate to childhood obesity, in terms of etiological pathways and intervention strategies (1,2). Maternal restriction of child eating, but no other feeding style, is associated with increased child energy intake and weight status (2). Parents restrict child food intake partially in response to child overeating and weight characteristics (3,4), although restriction may exacerbate child weight gain by promoting eating in the absence of hunger (5), or by making “forbidden foods” more desirable (1,6).

A barrier to this literature has been a lack of validated instruments for quantifying parental feeding behaviors and styles. In a review of 22 studies (2), only the Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ) (7) was cross-validated in pediatric samples and used in multiple laboratories. Demand cognitions (eg, “My child must eat what I serve”) may underlie certain feeding practices, as parents with more rigid beliefs may be more likely to attempt to influence the type or amount of food their children eat. Moreover, no instruments explicitly measure parental “demand cognitions” concerning child eating—that is, beliefs that children should comply with parental rules for eating. Measuring such beliefs may be important clinically, especially for understanding restrictive feeding practices.

The purpose of the present investigation was to evaluate the psychometric properties of a new questionnaire assessing parental demand cognitions concerning parent–child feeding relations. Validation was conducted by examining the instrument’s factor structure, internal consistency, convergent and discriminant validities, and readability. We also tested whether scores on the instrument were associated with child and parent anthropometric measures and mother demographic variables. We predicted that the psychometric evaluations, collectively, would support the validity of the new instrument. Specifically, it was predicted that principle components analysis of the Feeding Demands Questionnaire would reveal one underlying factor, and that this factor would reflect parental tendency to have demanding cognitions about how children should eat. It was predicted that the total Feeding Demands Questionnaire score would show an acceptable internal consistency (ie, Cronbach’s α ≥.80) and would be associated with parental restrictive feeding practices on the CFQ. It was predicted that the instrument’s readability would not be higher than a high-school reading level.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 85 mothers of twin or sibling pairs, as well as the actual twins and siblings (n = 170 children). They were participants in a study investigating familial influences on child eating patterns (8,9). Children who were twins (n = 132) were all same-sex (ie, boy-boy or girl-girl pairs), while nontwin siblings (n = 38) were either same-sex or mixed-sex. All ethnic groups were eligible to participate. Age range of the children was 3 to 7 years. A more detailed description of this sample is provided elsewhere (8–10).

MEASURES

Child Demographic Variables

Child age, sex, and ethnicity were provided by mother-report. Ethnicity was coded as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, and Other/Missing. For data analyses, we created a dummy-coded variable for ethnicity (ie, 0 = white and 1 = non-white). Child body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a Weight-Tronix electronic scale (Scale Electronics Development, New York, NY). Height was measured without shoes to the nearest 0.5 cm using a stadiometer (Holtain, Crosswell, Wales, UK). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as kg/m2 (11). All measurements were carried out at the Body Composition Laboratory of the New York Obesity Research Center, Columbia University. All measurements were taken by a trained laboratory technician using an established laboratory protocol for studies conducted with pediatric samples (12,13). Anthropometric data were not obtained on 24 children (five twin pairs and seven sibling pairs), as these children and/or their parents declined to have child body composition evaluated. This yielded a final sample of 146 children on whom anthropometric measures were collected.

Mother Demographic Variables

Maternal age, ethnicity, education, weight, and height were self-reported by mothers. Ethnicity was coded in the same manner as for children. Educational attainment was coded as less than high school, high school, college, or graduate school. Height and weight were used to compute BMI for mothers. Seven mothers did not report their heights or weights and were not included in the analyses (two of these mothers also had twin or sibling pairs with missing BMI z score data).

Feeding Demand Questionnaire

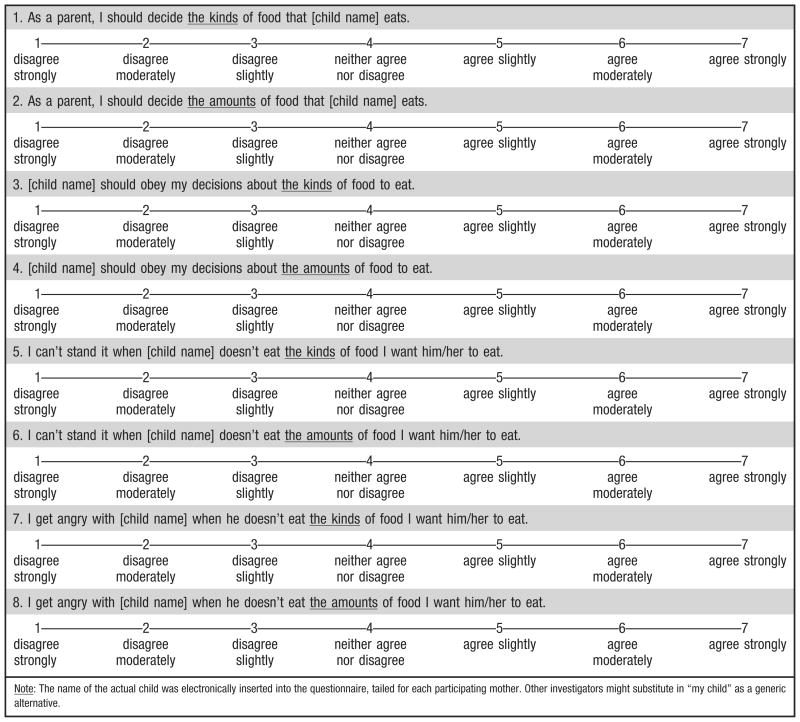

This eight-item questionnaire was designed to measure the extent to which parents endorse demand or control cognitions regarding feeding relations with their children (see Figure). The response format for each items was a 1 to 7 Likert scale, with higher numbers reflecting greater agreement with a demand cognition (1 = disagree strongly; 2 = disagree moderately; 3 = disagree slightly; 4 = neither agree nor disagree; 5 = agree slightly; 6 = agree moderately; 7 = agree strongly). Items were worded to reflect demand cognitions with respect to both the kind of food eaten by the child as well as the amount of food eaten. Items comprising the Feeding Demands Questionnaire were iteratively written, refined, and finalized by the authors based on theoretical discussions about the underlying construct and clinical experiences working with parents.

Figure.

The Feeding Demands Questionnaire (FEEDS).

Child Feeding Questionnaire

Parental feeding styles were measured by the Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ) (7). The following three feeding styles were evaluated: “Restriction,” the extent to which parents attempt to restrict their child’s eating during meals (eight items). “Pressure to Eat,” parents’ inclination to pressure their child to consume more food (four items). “Monitoring,” the degree to which parents monitor their child’s fat intake (three items). The range of scores on each of these CFQ subscales was 1 to 5, with higher scores reflecting greater amounts of the respective feeding practices.

Fear of Fat Scale

The 10-item Fear of Fat Scale is a widely used measure to evaluate attitudes toward being overweight, with higher scores reflecting more negative attitudes (14). The range of scores on the Fear of Fat Scale is 10 to 40, with higher scores reflecting greater fear of fat.

Center for Epidemiological Centers of Depression Inventory (CES-D)

The 20-item CES-D measures current level of depressive symptomatology and affect, including feelings of guilt and worthlessness, feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, loss of appetite, sleep disturbance, and psychomotor retardation. Higher scores reflect greater depression symptomatology (15). The range of scores on the CES-D scale is 0 to 60, with higher scores reflecting greater depressive symptoms. A score of 16 or higher is considered a threshold for possible clinical depression. In the present sample, 23 mothers had a CES-D score of 16 or higher.

PROCEDURES

Mothers completed questionnaires in the laboratory or at home as part of a survey addressing child nutrition and eating practices (8). Specifically, the questionnaire packet was provided in the laboratory, where most mothers completed the items as their children consumed protocol lunch meals (data not provided in this report). A minority of mothers did not complete the questionnaire packet in the laboratory, either because they did not have enough time to finish the packet completely or because they preferred to complete the full packet (beginning to end) at home. Instructions for all the questionnaires were fully contained in the packets and, therefore, were amenable to being completed in the laboratory or at home. Analyses were not stratified based on whether questionnaires were partially or fully completed at home, although there was no a priori reason to predict that location of questionnaire completion would impact on the results. Mothers completed the Feeding Demands Questionnaire and CFQ separately for each twin or sibling (ie, twin/sibling 1 and twin/sibling 2, respectively). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of St Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital. All mothers provided informed consent.

Data Analytic Strategy

Descriptive data are presented as means and standard deviations. The factor structure of the Feeding Demands Questionnaire items was examined using principal component analysis with Varimax rotation. Any item with a factor loading of ≥0.50 was considered to load on the given factor, in conjunction with a review of the content of the individual items. As noted later, the principal component analysis yielded three meaningful factors for which we created subscale scores by summing the appropriate items (ie, four items for the first subscale and two items for the second and third subscales). Internal consistency of the Feeding Demands Questionnaire was tested by Cronbach’s α.

To test for convergent validity, we correlated the total and subscale scores of the Feeding Demands Questionnaire against the CFQ subscale scores. Pearson’s correlations coefficients were computed. Significant correlations with the Restriction subscale would provide evidence for convergent validity, in that parents who limit or restrict child access to certain foods at home would be expected to have more demanding cognitions about child eating compared to parents who are less restrictive. To test for discriminant validity, we correlated the Feeding Demands Questionnaire total and subscale scores with maternal fear of fat and depression symptoms to establish a lack of association. Because the Feeding Demands Questionnaire is intended to measure a construct that is distinctly different from depression and fear of fat, it was predicted that that the Feeding Demands Questionnaire would not show a significant association with these other variables. Associations between the Feeding Demands Questionnaire and participant demographic variables were tested with correlational analyses and analyses of variance. To bypass a potential dependency in the data structure due to familial relatedness, separate analyses were conducted for twin/sibling 1 and twin/sibling 2, respectively (16). (Assignment of twins/siblings to group 1 or 2 within families was determined randomly and was unrelated to age in the case of sibling pairs.) Readability was assessed by Flesch-Kincaid index (17), which assesses readability based on the average number of syllables per word and the average number of words per sentence.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Demographic characteristics of participating mothers and children are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Descriptive information on the demographic, anthropometric, and psychosocial measures of mothers completing the Feeding Demands Questionnairea

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| ← mean±standard deviation → | |

| Body mass indexb | 28.37±9.85 |

| Fear of fat | 18.20±6.16 |

| Depression level | 11.73±9.01 |

| Age (y) | 35.55±6.93 |

| ←% → | |

| Educational attainment (%): | |

| <High school | 4.7 |

| High school | 37.6 |

| College | 37.6 |

| Graduate | 20 |

| Ethnicity (%) | |

| White | 46 |

| Non-white | 54 |

Valid scores were obtained on all 85 mothers except for the following variables, due to missing data: body mass index (n = 78), ethnicity (n = 84), fear of fat (n = 83), and depression (n = 80). Ethnicity breakdown for the 54% who were non-white subsample was: 23% non-Hispanic black, 19% Hispanic, 3% Asian, 1% Native American, and 8% not specified.

Calculated as kg/m2.

Table 2.

Descriptive information on the demographic and anthropometric measures of children whose mothers completed the Feeding Demands Questionnaire, by twin/sibling group

| Variable | Twin/sibling group 1 | Twin/sibling group 2 |

|---|---|---|

| n | 85 | 85 |

| Sex (% female) | 54.1 | 55.3 |

| ← mean±standard deviation → | ||

| BMIab | 16.13±2.70 | 16.47±3.83 |

| BMI z scoreb | 0.24±0.99 | 0.11±0.99 |

| Age (y) | 4.56±1.45 | 4.33±2.08 |

BMI = body mass index; calculated as kg/m2.

Sample size for BMI and BMI z score is n = 68 for sibling group 1 and n = 67 for sibling group 2.

Principal Components Analysis

The Feeding Demands Questionnaire had three distinct factors. Items 5 to 8 loaded onto the first factor (with loadings of 0.81, 0.78, 0.87, and 0.85, respectively), accounting for 44% of the variance; items 2 and 4 loaded onto the second factor (with loadings of 0.89 and 0.87, respectively), accounting for 24% of the variance; and items 1 and 3 loaded onto the third factor (with loadings of 0.83 and 0.84, respectively), accounting for an additional 13% of the variance. Based on the specific item loadings, the factors were labeled: “Anger/Frustration,” “Food Amount Demandingness,” and “Food Type Demandingness,” respectively. Descriptive data for the Feeding Demands Questionnaire, as well as the CFQ, are presented in Table 3. With respect to distributions of the three subscales, the Food Amount Demandingness sub-scale was not significantly skewed (Skew/SEskew = 1.18), although the Food Type Demandingness (Skew/SEskew = −2.69) and Food Type Demandingness (Skew/SEskew = −4.06) subscales were substantially negatively skewed.

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations for the Feeding Demands Questionnaire and the Child Feeding Questionnaire by twin/sibling group

| Variable | Twin/sibling group 1 | Twin/sibling group 2 |

|---|---|---|

| ← meana±standard deviation → | ||

| Total FEEDSb score | 32.31±7.50 | 32.23±8.74 |

| FEEDS factor 1; Anger/Frustration | 12.24±4.93 | 12.74±5.83 |

| FEEDS factor 2; Food Amount Demandingness | 8.93±3.24 | 8.69±3.08 |

| FEEDS factor 3: Food Type Demandingness | 11.10±2.07 | 10.81±2.38 |

| CFQc Monitoring | 3.60±1.01 | 3.46±1.06 |

| CFQ Restriction | 2.90±0.71 | 2.90±0.84 |

| CFQ Pressure to Eat | 2.67±1.04 | 2.64±1.05 |

Means were not significantly different between twin/sibling groups 1 and 2 for any of the measures.

FEEDS = Feeding Demands Questionnaire.

CFQ = Child Feeding Questionnaire.

Internal Consistency

The total Feeding Demands Questionnaire scale had an internal consistency of Cronbach’s α = .81. Cronbach α for the Anger/Frustration, Food Amount Demandingness, and Food Type Demandingness subscales were .86, .86, and .70, respectively, indicating acceptable internal consistencies.

Readability

The total Feeding Demands Questionnaire scale, comprising all 8 items, was written at a 4.8th grade level.

Convergent Validity

For the full Feeding Demands Questionnaire scale, mothers who had higher scores were more likely to pressure children to eat (P<0.01) and to monitor child fat intake (P<0.01) (Table 4). They were also more likely to restrict child eating (P = 0.02) in twin/sibling group 1 only. For the Anger/Frustration subscale, mothers with higher scores were more likely to pressure their children to eat (P<0.001). For the Food Amount Demandingness subscale, mothers with higher scores were more likely to restrict child eating (P<0.05), pressure children to eat (P≤0.01) and to monitor child fat intake (P<0.01). For the Food Type Demandingness sub-scale, mother with higher scores were more likely to monitor child fat intake (P<0.01).

Table 4.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient for associations between scores on the Feeding Demands Questionnaire and the Child Feeding Questionnaire, mother attributes, and child body mass index z score by twin/sibling group (group 1 or 2)

| Variable | Anger/Frustration |

Food Amount Demandingness |

Food Type Demandingness |

Full FEEDSa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 1 | Group 2 | |

| CFQb Monitoring | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.45** | 0.29** | 0.36** | 0.43** | 0.36** | 0.30** |

| CFQ Restriction | −0.03 | 0.17 | 0.26* | 0.24* | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.25* |

| CFQ Pressure to Eat | 0.47** | 0.32** | 0.46** | 0.38** | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.53** | 0.41** |

| Mother fear of fat | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.08 | −0.07 | −0.14 | 0.16 | 0.06 |

| Mother depression | 0.30** | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.28* | 0.14 |

| Mother BMIc | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.27* | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.17 |

| Mother age | −0.16 | −0.09 | −0.43* | −0.22* | −0.03 | −0.08 | −0.21 | −0.16 |

| Mother ethnicity | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.42** | 0.32** | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.22* | 0.17 |

| Child BMI z score | −0.26* | 0.12 | −0.07 | 0.17 | −0.11 | 0.02 | −0.22 | 0.14 |

FEEDS = Feeding Demands Questionnaire.

CFQ = Child Feeding Questionnaire.

BMI = body mass index; calculated as kg/m2

P≤0.05.

P<0.01.

Discriminant Validity

The Feeding Demands Questionnaire total and subscale scores were not significantly correlated with maternal fear of fat or depression (P>0.05) (Table 4). Depression levels were not associated with any of the Feeding Demands Questionnaire subscales except for a positive association with the Anger/Frustration subscale (r = 0.30, P = 0.006) and the total Feeding Demands Questionnaire score (r = 0.28, P = 0.01) in twin/sibling group 1 only.

Relationship between Child Weight Status and the Feeding Demands Questionnaire

Child BMI z score showed no significant association with any of the Feeding Demands Questionnaire subscales, except for a negative association with Anger/Frustration scores in twin/sibling group 1 only (r = −0.26, P = 0.03) (Table 4). Thus, mothers of thinner children reported greater anger and frustration in feeding relations with their child than mothers of heavier children.

Relationship Between Mother Characteristics and the Feeding Demands Questionnaire

Maternal BMI, age, and ethnicity all showed significant associations with the Food Amount Demandingness subscale, but none of the other subscales (Table 4). Maternal age was significantly negatively associated with Food Amount Demandingness (P≤0.05), such that younger mothers were more demanding about the amount of food their children ate than were older mothers. Maternal BMI was significantly positively associated with Food Amount Demandingness scores in twin/sibling group 1 (r = 0.27, P = 0.03) and showed a nonsignificant trend in twin/sibling group 2 (r = 0.19, P = 0.09), such that heavier mothers were more demanding about the amount of food their children eat than were thinner mothers. Finally, maternal ethnicity status was significantly associated with the Food Amount Demandingness subscale (P<0.01), such that not non-Hispanic white mothers were more demanding about the amount of food their children eat than non-Hispanic white mothers.

DISCUSSION

The present study supports the validity of a new instrument measuring maternal demands and frustration/anger surrounding feeding interactions with young children. The Feeding Demands Questionnaire showed reasonable internal consistency, as well as convergent and discriminant validities. The instrument was only eight items and written at a 4.8th grade level, making it possible to be administered to adults from diverse educational backgrounds. That the instrument was validated on a sample of 3- to 7-year-old children is also noteworthy, as this age range corresponds to the developmental period of “adiposity rebound,” which may be critical period for obesity onset. [Others, however, have challenged whether adiposity rebound is a true developmental phenomenon or statistical artifact (18)].

A main finding of the study is that different maternal beliefs about feeding relations corresponded to different feeding practices. Maternal frustration with child eating was related to greater pressures on children to eat, whereas maternal demands about the type of foods children eat was associated with greater monitoring of child fat intake. Interestingly, maternal demands about the amount of foods children eat was associated with greater feeding restriction, pressure to eat, and monitoring child fat intake. These are the first findings to show that distinct parent demand beliefs may underlie different feeding practices. Understanding the development of child feeding practices, therefore, may require a better understanding of parental thoughts about feeding relations and demands that may be imposed on these relations. More precise measurement tools may be needed, including questionnaires or standardized interviews, to assess these beliefs.

Food Amount Demandingness, but no other Feeding Demands Questionnaire subscale, was associated with mother ethnicity, BMI, and age. Mothers who were not non-Hispanic white reported greater feeding demands than mothers who were non-Hispanic white, an interesting finding that needs replication. Few studies have tested for ethnicity differences in parental feeding practices and there has not been a consistent pattern of findings to date. Compared to non-Hispanic white mothers, non-Hispanic black mothers reported greater monitoring, feelings of responsibility, restrictive practices, pressure to eat, and concern for child weight in a cohort of families from Alabama (19). However, in a secondary analysis of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, mothers of Hispanic and non-Hispanic black children reported that they allot greater food choice during breakfast and lunch to their children than mothers of non-Hispanic white children (20). These issues are important, given existing ethnicity disparities for childhood overweight (21,22) and warrant additional research (23,24).

Mothers who were more demanding about the type of foods their children eat scored higher on the monitoring scale from the CFQ, suggesting that these mothers were especially attentive to their child’s intake of higher fat foods. It is conceivable, however, that higher Food Type Demandingness scores also apply to certain foods others than just high fat foods per se (eg, certain mothers may be demanding about the types of beverages their children drink and limit fruit juice intake). This cannot be ruled out because, although the Monitoring subscale focuses on energy-dense higher-fat foods, parents may still place demands on other particular types of foods or beverages.

There was some evidence that heavier mothers had greater food amount demands than thinner mothers, an intriguing finding because this was the only Feeding Demands Questionnaire subscale associated with greater restrictive feeding practices. Restrictive feeding may stem, in part, from specific parental beliefs or rules about how much children should eat, rather than from beliefs about the types of food children should eat or from feeling frustrated. Future studies should replicate the present findings and explore the criteria parents use for determining an “appropriate amount” of food their children should eat. These criteria may not necessarily agree with dietary guidelines (25).

Younger mothers placed more demands on children than older mothers concerning the amount of food they eat, an interesting finding given that caregiver age effects have not been studied in this literature. This finding could be due to a number of factors. It may be the case, for example, that older and more experienced mothers are more comfortable with their children’s eating and, therefore, are less likely to impose demands on how much their children eat. There has been little research examining to what extent life experiences, including having more children, influence mothers’ attitudes and feeding practices. Mothers may make adjustments in how they feed children based on their learning experiences.

It should be noted that, on the Food Amount Demandingness subscale, higher scores do not necessarily refer to demanding that children eat more (or less) food. That is, one cannot infer the directionality of the amount of food that the respondent demands to be eaten. In certain families, such as those with a history of obesity and type 2 diabetes, there could be parental greater demands for the child to eat less food. In other families, such as those with food insecurity, there could be parental demand for the child to eat more food. The present scale cannot discriminate these two hypothetical situations in which Food Amount Demandingness scores would be elevated but the parental intention is for the child to eat either less or more food, respectively. Future studies should address this issue, using a more diverse set of families in terms of socioeconomic status and ethnicity.

Results of the present study should be interpreted in light of the study limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, although there was variability in socio-demographic variables. The present findings should be replicated and followed up on larger and more diverse families. Second, fathers or male caregivers were not studied in the present report. Third, results may not be generalizable to older children and adolescents, who should be studied in subsequent research. Fourth, the generalizability of the present findings to parents of singletons was not tested in this investigation and should be evaluated. Finally, we did not evaluate the instrument’s test-retest reliability, which should be examined in future research.

There are a number of important issues for future research. One important avenue is to identify the factors influencing how parents make rules for child feeding practices. For example, do parents have a standard for how much (ie, portion size) they serve their children? If so, does this portion-size norm reflect parents’ thoughts about how much they think their children would eat or how much parents typically serve themselves when eating? Or, are there visual cues, such as plate or bowl size, that determine the quantity to be consumed? It is also unknown whether it is advisable for all children in the same family to eat the same size portions in spite of age differences. Finally, will the “feeding relationship” carry over into broader communication patterns, with the parent such that the satiated child is inhibited from signaling that they have eaten enough. Finally, another interesting question for future research is parity and how the number of children in a family impacts on feeding attitudes and practices.

In conclusion, the Feeding Demands Questionnaire appears to be valid for assessing maternal beliefs that children should comply with their rules for eating certain amounts and types of foods, as well as feelings of frustration in feeding interactions. The findings also suggest that different demand beliefs may underlie different feeding practices, which has implications for understanding the development of parent–child feeding relations. Clinically, efforts to modify specific child feeding practices for obesity prevention may need to evaluate carefully underlying beliefs. Additional research on these issues is needed. The Feeding Demands Questionnaire offers a complementary tool to the CFQ for understanding feeding relations that might be linked to child weight status.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant K08MH01530.

Contributor Information

MYLES S. FAITH, Assistant professor of Psychology in Psychiatry and Pediatrics, the Center for Weight and Eating Disorders, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia.

MEGAN STOREY, School psychologist, in Monterey, CA.

TANJA V. E. KRAL, Assistant professor of Nutrition in Psychiatry, Center for Weight and Eating Disorders, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia.

ANGELO PIETROBELLI, Senior physician, Pediatric Unit, University of Verona School of Medicine, Verona, Italy.

References

- 1.Birch LL, Fisher JO. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101:539–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faith MS, Scanlon KS, Birch LL, Francis LA, Sherry B. Parent-child feeding strategies and their relationships to child eating and weight status. Obes Res. 2004;12:1711–1722. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Francis LA, Hofer SM, Birch LL. Predictors of maternal child-feeding style: Maternal and child characteristics. Appetite. 2001;37:231–243. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faith MS, Berkowitz RI, Stallings VA, Kerns J, Storey M, Stunkard AJ. Parental feeding attitudes and styles and child body mass index: Prospective analysis of a gene-environment interaction. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e429–e436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1075-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birch LL, Fisher JO, Davison KK. Learning to overeat: maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls’ eating in the absence of hunger. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:215–220. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birch LL, Birch D, Marlin DW, Kramer L. Effects of instrumental consumption on children’s food preference. Appetite. 1982;3:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(82)80005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birch LL, Fisher JO, Grimm-Thomas K, Markey CN, Sawyer R, Johnson SL. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: A measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite. 2001;36:201–210. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faith MS, Keller KL, Matz P, Johnson SL, Lewis R, Jorge MA, Ridley C, Han H, Must S, Heo M, Pietrobelli A, Heymsfield SB, Allison DB. Project Grow-2-Gether: A study of the genetic and environmental influences on child eating and obesity. Twin Res. 2002;5:472–475. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faith MS, Keller KL, Johnson SL, Pietrobelli A, Matz PE, Must S, Jorge MA, Cooperberg J, Heymsfield SB, Allison DB. Familial aggregation of energy intake in children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:844–850. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pietrobelli A, Keller K, Wang J, Heymsfield SB, Allison DB, Faith MS. Genetic and environmental influences on child waist circumference independent of body mass index Z-Score: Evidence from a pediatric twin cohort. Obes Res. 2005;13(suppl):A182. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Guo S, Wei R, Grummer-Strawn LM, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: Improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002;109:45–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freedman SD, Wang J, Maynard LM, Thornton JC, Mei Z, Pierson RN, Dietz WH, Horlick M. Relation of BMI to fat and fat-free mass among children and adolescents. Int J Obes. 2005;29:1–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horlick M, Wang J, Pierson RN, Jr, Thornton JC. Prediction models for evaluation of total-body bone mass with dual energy X-ray absorptiometry among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e337–e345. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldfarb LA, Dykens EM, Gerrard M. The Goldfarb Fear of Fat Scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49:329–332. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4903_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ensel WM. Measuring depression: The CES-D Scale. In: Lin A, Dean A, Ensel WM, editors. Social Support, Life Events, and Depression. New York, NY: Academia Press; 1986. pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wardle J, Sanderson S, Guthrie CA, Rapoport L, Plomin R. Parental feeding style and the inter-generational transmission of obesity risk. Obes Res. 2002;10:453–462. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kincaid RP, Fishburne RL, Rogers BL, Chissom BS. Derivation of the New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count, and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel. Memphis, TN: Research Branch Report, Chief of Naval Technical Training; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole TJ. Children grow and horses race: Is the adiposity rebound a critical period for later obesity? BMC Pediatr. 2004;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spruijt-Metz D, Lindquist CH, Birch LL, Fisher JO, Goran MI. Relation between mothers’ child-feeding practices and children’s adiposity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:581–586. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faith MS, Heshka S, Keller KL, Sherry B, Matz PE, Pietrobelli A, Allison DB. Maternal-child feeding patterns and child body weight: Findings from a population-based sample. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:926–932. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.9.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1728–1732. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Epidemiologic trends in overweight and obesity. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32:741–760. vii. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(03)00074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baughcum AE, Burklow KA, Deeks CM, Powers SW, Whitaker RC. Maternal feeding practices and childhood obesity: A focus group study of low-income mothers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:1010–1014. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.10.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baughcum AE, Chamberlin LA, Deeks CM, Powers SW, Whitaker RC. Maternal perceptions of overweight preschool children. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1380–1386. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]