SUMMARY

The biologic and clinical significance of KIT overexpression that associates with KIT gain-of- function mutations occurring in subsets of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (i.e., core binding factor AML) is unknown. Here, we show that KIT mutations lead to MYC-dependent miR-29b repression and increased levels of the miR-29b target Sp1 in KIT-driven leukemia. Sp1 enhances its own expression by participating in a NFκB/HDAC complex that further represses miR-29b transcription. Upregulated Sp1 then binds NFκB and transactivates KIT. Therefore, activated KIT ultimately induces its own transcription. Our results provide evidence that the mechanisms of Sp1/NFκB/HDAC/miR-29b-dependent KIT overexpression contribute to leukemia growth and can be successfully targeted by pharmacological disruption of the Sp1/NFκB/HDAC complex or synthetic miR-29b treatment in KIT-driven AML.

INTRODUCTION

The KIT gene encodes a 145 kDa transmembrane protein that is a member of the type III receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) family (Yarden et al., 1987), regulates cell survival, proliferation or differentiation (Schlessinger et al, 2000) and participates in normal mechanisms of hematopoiesis, melanogenesis and gametogenesis. KIT protein expression is modulated by a variety of mechanisms including microRNAs (miRNAs) (Felli et al., 2005) and/or proteolytic degradation (Masson et al., 2006), and is subjected to covalent posttranslational modifications, which influence its tyrosine kinase activity through interaction with a variety of factors including KIT ligand (also known as stem cell factor), tyrosine phosphatases (Kozlowski et al., 1998), protein kinase C and calcium ionophores (Miyazawa et al., 1994; Yee et al., 1993).

KIT is overexpressed and/or mutated in several human neoplasms, including gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), germ cell tumors and hematologic malignancies (Ikeda et al., 1991). In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), while KIT expression is detectable in the majority of the cases (Ikeda et al., 1991), gain-of-function mutations resulting in constitutive tyrosine kinase activity appear to be restricted to core binding factor (CBF) disease [t(8;21) or inv(16) or the respective molecular equivalent RUNX1/RUNX1T1- or CBFB/MYH11-positive AML], where these mutations associate with unfavorable outcome (Paschka et al., 2006).

Tyrosine kinase (TK) inhibitors [e.g., imatinib, dasatinib or PKC412 (midostaurin)] have been shown to suppress aberrant activity of KIT mutants and delay tumor growth (Heinrich et al., 2002; Growney et al., 2005). However, clinical response to these compounds depends mostly on the nature of KIT mutations (Heinrich et al., 2002). For example, KIT mutations in codon 822 are sensitive to imatinib, whereas mutations in codon 816 are not and can be targeted successfully with midostaurin or dasatinib. Therefore, to take fully clinical advantage of the therapeutic approach with inhibitors, the type of the KIT mutations needs to be identified at the time of initial diagnosis. Even if this strategy is adopted, however, the sensitivity of a distinct KIT mutation to an optimally chosen TK inhibitor is likely to decrease over time due to acquisition of secondary KIT mutations (Gajiwala et al., 2009) that mediate resistance (Heinrich et al., 2008). These observations justify investigation of novel strategies to effectively target all KIT mutations and improve the likelihood of inducing durable clinical responses in KIT-driven malignancies. Flavopiridol and KIT siRNA have been shown to downmodulate KIT transcription and induce apoptosis in GIST cells (Sambol et al., 2006). Therefore direct targeting of KIT expression may represent a valuable approach to overcome aberrant KIT enzymatic activity and circumvent the drawbacks of TK inhibitor therapies in AML. This strategy, however, can be effectively developed and implemented only if the regulatory mechanisms controlling the expression of both the wild-type and mutated KIT alleles in myeloid cells are elucidated.

The overarching goal of the present study is to characterize the molecular pathways that control aberrant expression of both wild type and mutated KIT alleles in AML and devise molecular targeting strategies to downregulate KIT and, in turn, attain significant and durable antileukemic activity in KIT-driven leukemia.

RESULTS

KIT overexpression in AML

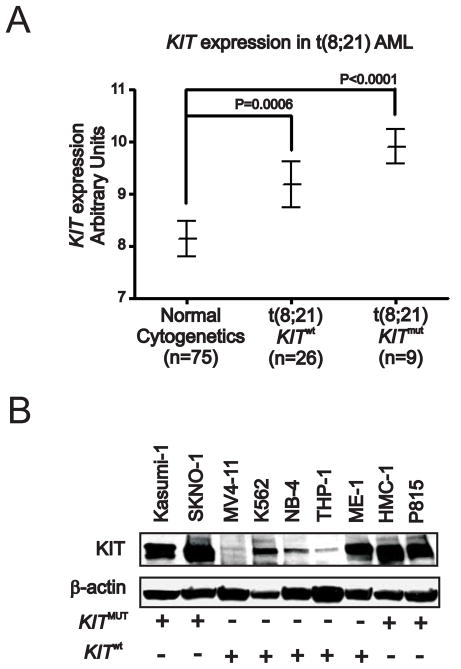

Aberrant KIT protein activity plays a pivotal role in human malignancies. While KIT expression is relatively common in blasts from all AML subtypes, activating KIT mutations appear to be restricted to CBF AML, where they predict poor outcome (Paschka et al., 2006). In CBF AML, the KIT gene appears to be also overexpressed. In a cohort of Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) patients, we showed that RUNX1/RUNXT1-positive patients with KIT mutation (KITmut) or wild-type (KITwt) have higher KIT levels compared with patients with cytogenetically normal (CN) AML (Figure 1A). Interestingly, KIT overexpression impacts adversely on outcome and RUNX1/RUNXT1-positive patients with higher KIT levels had a significantly shorter survival (P=.04; Supplemental Figure S1A). Among AML cell lines, higher levels of KIT expression are also found in CBF AML cell lines, i.e., RUNX1/RUNXT1-positive and KITmut Kasumi-1 and SKNO-1 and CBFB/MYH11-positive and KITwt ME-1, when compared with non-CBF cell lines (Figure 1B and Supplemental Figure S1B). Thus, we hypothesized that in distinct molecular subsets of AML like CBF AML, the KIT protein is aberrantly activated and upregulated. We also hypothesized that KIT overexpression itself contributes to leukemogenesis and therefore should be therapeutically targeted in KIT-driven AML. In order to prove these hypotheses, however, the mechanisms that govern KIT expression and its leukemogenic role in KIT-driven leukemia need to be fully elucidated.

Figure 1. KIT expression in AML patients and cell lines.

(A) KIT expression in bone marrow from Cancer and Leukemia Group B AML patients.

(B) KIT protein expression in various AML or mastocytosis (HMC-1) cell lines. + or − indicate presence or absence of KITmut or KITwt alleles. Data are representatives of three independent experiments. (See also Figure S1)

Sp1/NFκB modulates KIT expression in AML

To start unraveling the regulatory mechanisms of KIT expression in AML, we examined the KIT promoter region for transcription factor binding sites, and identified binding sites for both Sp1 and NFκB in a 1kb region spanning the human KIT gene promoter. As we and others have recently shown that transactivation of certain oncogenes (e.g., DNMT1) involved in leukemogenesis requires physical interaction of the transcription factors Sp1 and NFκB (Liu et al., 2008; Hirano et al., 1998), we reasoned that the Sp1/NFκB complex is likely to be also involved in modulation of KIT expression in KIT-driven leukemia cells.

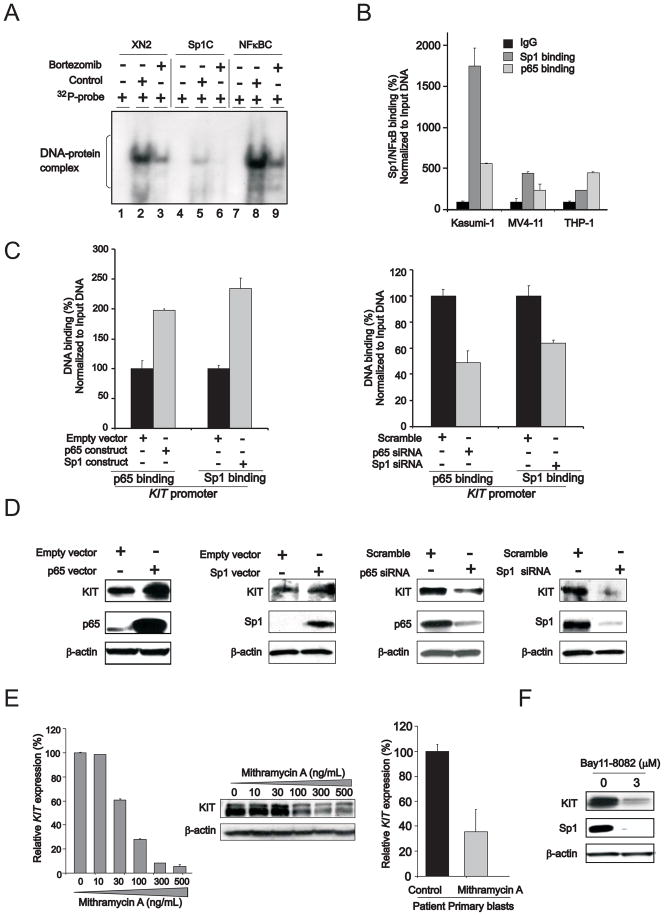

To support this hypothesis, electrophoretic mobility-shift assays (EMSA) were performed using probes spanning the Sp1/NFκB binding sites (XN2 probe) on the KIT promoter or consensus binding elements for Sp1 (Sp1C) or NFκB (NFκBC) on nuclear extracts from Kasumi-1 cells. These cells were selected because they harbor mutated and overexpressed KIT (Figure 1B). The DNA-protein complexes attained with the XN2 probe co-migrated with those attained with the Sp1C and NFκBC probes, supporting enrichment of both Sp1 and NFκB on the KIT promoter (Figure 2A, lanes 2, 5 and 8). These data were confirmed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) showing Sp1 and NFκB enrichment on the KIT promoter (Figure 2B). Higher level of Sp1 enrichment on the KIT promoter was observed in Kasumi-1 cells that harbor overexpressed KITmut compared with AML lines (MV4-11 and THP-1) carrying lower levels of KITwt (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. The regulatory role of Sp1/NFκB in KIT expression.

(A) Sp1/NFκB complex is present on KIT promoter. EMSA was performed with nuclear extracts from Kasumi-1 cells incubated with 32P-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides containing Sp1/NFκB binding elements on the KIT promoter region from nucleotides -102/-82 (XN2) or Sp1 consensus binding sites (Sp1C) or NFκB consensus binding sites (NFκBC). Lanes 1, 4 and 7, free 32P-labeled probes; lanes 2, 5 and 8, control (untreated) cells; lanes 3, 6 and 9, bortezomib-treated cells.

(B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays to demonstrate Sp1/NFκB on KIT gene promoter in KITmut Kasumi-1 and KITwt MV4-11 and THP1 cells (mean ± SEM).

(C) ChIP assays to show Sp1/NFκB enrichment on KIT promoter in Kasumi-1 cells transfected with NFκB or Sp1 overexpression vector (left panel) or siRNAs (right panel) (mean ± SEM).

(D) Sp1, NFκB and KIT protein expression in Kasumi-1 cells transfected with corresponding overexpression vector (left panel) or siRNA (right panel).

(E) Sp1 inhibition by mithramycin A impaired KIT RNA transcription and protein expression in Kasumi-1 cells (left and middle panels) or patient primary blasts (right panel) (mean ± SEM).

(F) NFκB inhibitor bay11-7082 (3 μM) decreased KIT expression in Kasumi-1 cells.

Data are representatives of three independent experiments. (See also Figure S2)

To further assess the biological role of Sp1 and NFκB on KIT expression, loss- and gain-of function approaches were applied in Kasumi-1 cells. First we showed that ectopic expression (Figure 2C, left panel) or siRNA knock-out (Figure 2C, right panel) respectively reduced and increased Sp1 and NFκB(p65) enrichment on the KIT promoter, and resulted respectively in KIT down- or up-regulation in Kasumi-1 cells (Figure 2D). The role of Sp1 in KIT gene transcription was further elucidated by treating Kasumi-1 cells or AML patient primary blasts with mithramycin A, a previously reported Sp1 inhibitor (Ray et al., 1989). Mithramycin A exposure led to decrease in KIT RNA transcription and protein expression (Figure 2E) in both Kasumi-1 and patient primary cells and time- and dose-dependent inhibition of Kasumi-1 cell proliferation (Supplemental Figure S2). With regard to NFκB function, exposure to the NFκB inhibitor bay11-7082 decreased Sp1 and KIT expression (Figure 2F).

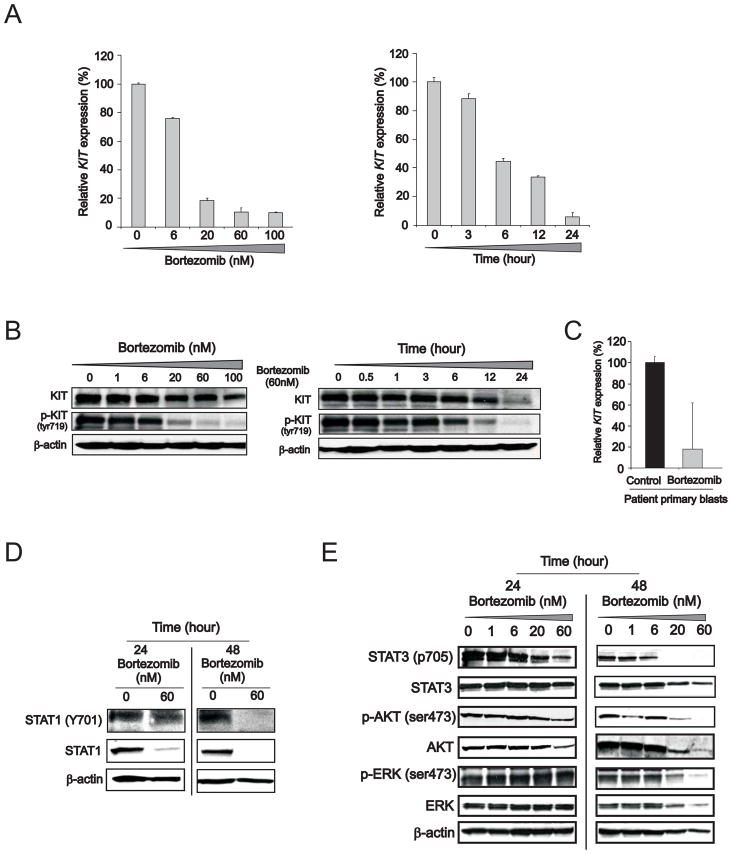

Sp1 expression and functions are, in part, regulated via the 26S proteasome, a common pathway controlling the degradation of a plethora of other survival factors (Karin et al., 2004; Pagano et al., 1995). Activation of NFκB is also controlled by the 26S proteasome (Bargou et al., 1997; Mori et al., 2000). We have also previously reported that the 26S proteasome inhibitor bortezomib interferes with the Sp1/NFκB activity (Liu et al., 2008). To further establish the regulatory role of the Sp1/NFκB complex in KIT expression, Kasumi-1 cells were then treated with bortezomib. The pharmacologic activity of bortezomib was then demonstrated by accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins indicating adequate proteasome inhibition, concurrent increase in expression of the Noxa and p21 genes and miR-29b occurring prior to any evidence of obvious cytotoxicity (Supplemental Figure S3A, B, C, D and G). In agreement with recent reports (Hideshima et al., 2009), we also observed that bortezomib resulted in NFκBp65 and IKBα phosphorylation (Supplemental Figure S3E), thereby suggesting possible activation of the NFκB canonical pathway in Kasumi-1 cells. Concurrent with these changes, however, we also evidenced increase in Sp1 ubiquitination, more diffused Sp1 nucleus/cytoplasm localization, and most importantly disruption of the Sp1 and NFκB physical interaction (Supplemental Figure S3E and F). The latter was likely to abrogate Sp1/NFκB gene transactivating activity thereby leading to bortezomib-induced dose- and time-dependent reduction in KIT expression (Figure 3A and B; see also Figure S3H) as observed in Kasumi-1 cells and confirmed in primary blasts from three RUNX1/RUNX1T1-positive and KITmut AML patients diagnosed at our institution (Figure 3C). Moreover, we found that bortezomib not only induced KIT downregulation, but also KIT dephosphorylation (Figure 3B) and inhibition of KIT-dependent downstream signaling effectors (Figure 3D). Decreased protein expression and phosphorylation of tyrosine (tyr) or serine (ser) residues of STAT1 (tyr701), STAT3 (tyr705), AKT (ser473) and ERK (tyr204) were observed in Kasumi-1 cells upon exposure to bortezomib (Figure 3E). Hence, these results support a critical role of both Sp1 and NFκB on KIT expression and in turn on KIT aberrant kinase activity in leukemia.

Figure 3. Proteasome inhibition by bortezomib impairs KIT expression and its downstream signaling pathway.

(A and B) Dose- (left) and time- (right) dependent reduction of KIT RNA and protein expression and KIT protein phosphorylation in tyrosine (tyr) 719 residue in Kasumi-1 cells incubated with bortezomib (mean ± SEM).

(C) Inhibitory effect of bortezomib on KIT mRNA expression was evaluated using qRT-PCR in AML blasts from three patients with mutated KITmut t(8;21) AML treated with 60 nM of bortezomib for 24 hours (mean ± SD).

(D and E) Immunoblotting analysis demonstrated the down-regulation of KIT downstream effectors such as STAT1 (D), STAT3, AKT and ERK (E) in Kasumi-1 cells treated with bortezomib. p, phosphorylated.

Data are representatives of three independent experiments. (See also Figure S3)

MiR-29b modulates KIT expression by targeting Sp1 through an autoregulatory loop

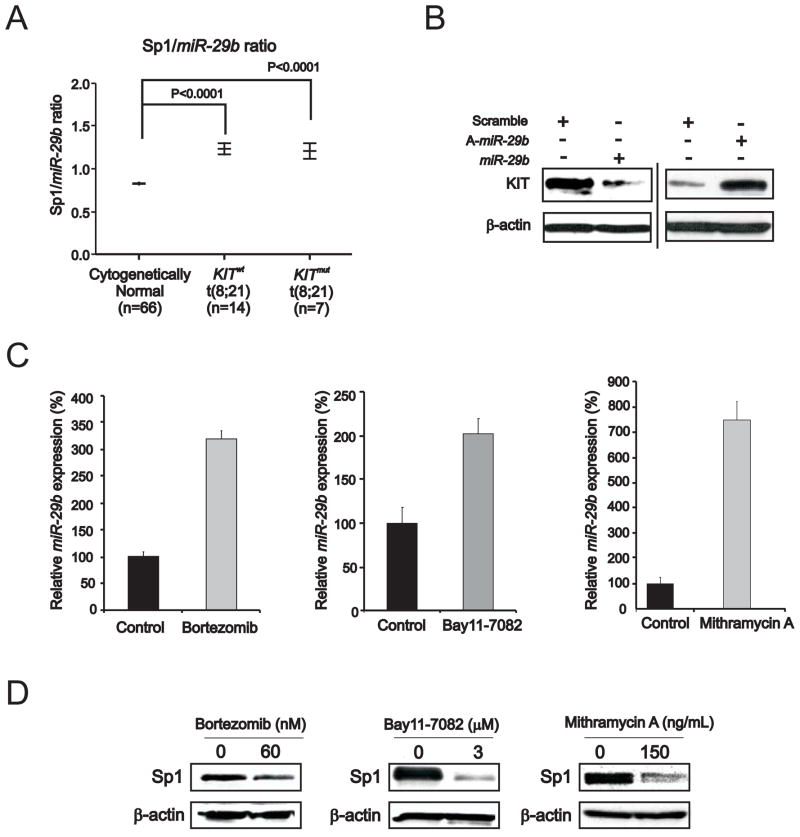

Sp1 is a bona fide target of miR-29b (Garzon et al., 2009). The clinical relevance of this finding was supported here by the negative linear correlation between Sp1 and miR-29b expression levels in RUNX1/RUNX1T1–positive AML patients (Spearman’s Coefficient Correlation .6; P=.016; Supplemental Figure S4A). Consistent with these results, these patients have high Sp1/miR-29b ratio (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Role of miR-29b in KIT expression regulation.

(A) Sp1/miR-29b expression ratio (measured by microarray) in bone marrow samples from Cancer and Leukemia Group B RUNX1/RUNX1T1-positive patients with cytogenetically normal AML and KITmut or KITwt.

(B) Changes in miR-29b expression and KIT protein levels in Kasumi-1 cells transfected with miR-29b or antagomiR-29b (A-miR-29b) for 72 hours.

(C) Up-regulation of miR-29b in Kasumi-1 cells treated with bortezomib (60 nM) or bay11-7082 (3 μM) or mithramycin A (150 ng/ml) for 6 hours. qRT-PCR analysis of miR-29b, normalized by U44, was performed (mean ± SEM).

(D) Immunoblotting analysis showing reduction of Sp1 protein in Kasumi-1 cells treated with bortezomib or bay11-7082 or mithramycin A.

Data are representatives of three independent experiments.

Given that miRNAs are frequently involved in feedback loops where they target the same factors that regulate their expression (Tsang et al., 2007) and Sp1 participates in KIT transactivation, we then hypothesized a microcircuity mechanism where Sp1 represses miR-29b transcription and this in turn increases Sp1 at levels sufficient to participate with NFκB in KIT transcriptional upregulation. Consistent with our hypothesis, forced miR-29b expression in Kasumi-1 cells led to KIT protein downregulation, while decreased miR-29b expression by antagomiR-29b led to upregulation of KIT (Figure 4B). Furthermore, exposure of Kasumi-1 cells to mithramycin A, bay11-7082 or bortezomib, that interfere respectively with Sp1, NFκB or Sp1/NFκB activities, resulted not only in KIT downregulation (Figures 2E and F; Figure 3A and B), but also in increased miR-29b expression (Figure 4C) and in turn downregulation of the miR-29b target Sp1 (Figure 4D). Collectively these data suggest that miR-29b participates in modulating KIT level by regulating expression of Sp1 and its participation in transcriptional regulation complexes with NFκB. The clinical relevance of the miR-29b in KIT-driven AML was supported by the observation that RUNX1/RUNX1T1–positive patients, who showed worse survival when expressing higher KIT levels, tended also to have worse outcome when expressing lower miR-29 levels (Supplemental Figure S4B).

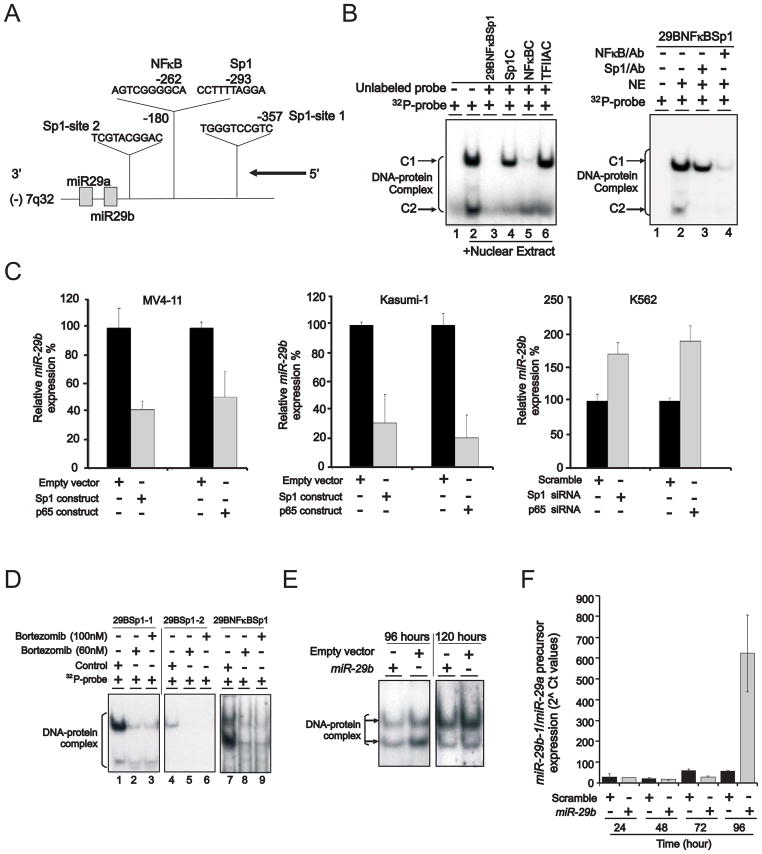

Next we focused on dissecting the mechanisms of miR-29b transcriptional regulation. We identified three Sp1 and one NFκB binding sites within a 1 kb span of DNA upstream from the 5′-end of the primary transcript of miR-29b on human chromosome 7 (using software package @ www.gene-regulation.com) (Figure 5A). To determine whether a functional interaction occurred between Sp1/NFκB and the miR-29b upstream regulatory sequence, we initially performed EMSA assays using probes (see supplementary material) spanning the -125/-75 miR-29b sequence in K562 cells. These cells were selected because they have high level of Sp1 while expressing low levels of endogenous miR-29b (Garzon et al., 2009). As shown in Figure 5B (left panel, lane 2), the 29BNFκBSp1 probe containing both Sp1 and NFκB binding sites yielded two major complexes (indicated as C1 and C2), suggesting that both Sp1 and NFκB interact with elements of the miR-29b enhancer region. The specificity of the protein-DNA binding complexes was demonstrated by their abrogation of binding in the presence of 100-fold excess of unlabeled probes (29BNFκBSp1, Sp1C or NFκBC containing both or single Sp1/NFκB binding site) (Figure 5B, left panel, lanes 3, 4 and 5), while the same-fold excess of an irrelevant oligonucleotide (TFIIAC) containing the TFIIA binding site failed to change the profile of these complexes (Figure 5B, left panel, lane 6). Interestingly, the unlabeled Sp1C probe preferentially decreased the C2 complex, while the unlabeled NFκBC probe decreased the C1 complex and eliminated the C2 complex. Similarly, incubation of extracts with Sp1 antibodies decreased the C1 complex and eliminated the C2 complex, whereas antibody to NFκBp65 decreased the intensity of both complexes (Figure 5B, right panel). These data suggest that the C1 and C2 complexes contained both Sp1 and NFκBp65, probably with different stoichiometry; C1 is likely to contain less Sp1. Similar results were attained in Kasumi-1 cells (data not shown).

Figure 5. Regulation of miR-29b transcription.

(A) Schematic diagram showing the location of Sp1 and NFκB binding sites on miR-29b-1 regulatory region on chromosome 7.

(B) EMSA demonstrated that Sp1/NFκB complex was present on the miR-29b regulatory region. Kasumi-1 nuclear extract incubated with 32P-29bNFκBSp1 probe containing NFκB and Sp1 binding sites yielded two DNA-protein complexes C1 and C2 (lane 2). The specificity of DNA binding was demonstrated by the abolishment or reduction of both complexes with excess (100x) unlabeled 29BNFκBSp1 (lane 3) or Sp1 consensus binding site (Sp1C, lane 4) or NFκB consensus binding site (NFκBC, lane 5) probes, but not with an irrelevant competitor probe that contains the TFIIA binding site (lane 6). The presence of NFκB and Sp1 in the DNA-protein complexes was demonstrated by antibody supershift assay (right panel).

(C) Changes in Sp1, NFκB and miR-29b levels in MV4-11, Kasumi-1 or K562 cell lines transfected with Sp1 or NFκB overexpression vector or siRNA (mean ± SEM).

(D) EMSA showed that bortezomib treatment diminished the binding of Sp1/NFκB complex to miR-29b regulatory region in Kasumi-1 cells. Control, untreated cells.

(E and F) miR-29b regulated its own transcription. Ectopic miR-29b expression dissociated Sp1 binding from its own regulatory region by EMSA (E) and synthetic mature miR-29b enhanced endogenous miR-29b precursor level (F) following 96 hours from initial treatment (mean ± SEM).

Data (B–F) are representatives of three independent experiments. (See also Figure S4)

Next, we used gain- and loss- of function assays to show that forced expression of Sp1 or NFκB(p65) reduced miR-29b in MV4-11, an AML cell line with relatively high endogenous miR-29b levels (Garzon et al., 2009), or Kasumi-1 cells (Figure 5C, left and middle panels). Conversely, Sp1 or NFκB(p65) knockdown by siRNAs resulted in miR-29b upregulation in K562 cells that have barely detectable levels of endogenous miR-29b (Garzon et al., 2009) (Figure 5C, right panel). Consistent with these results, bortezomib treatment reduced the binding of Sp1/NFκB complex to miR-29b regulatory elements (Figure 5D), thereby resulting in miR-29b re-expression (Figure 4C) and Sp1 reduction (Figure 4D). Notably, ectopic miR-29b expression disrupted Sp1 binding to the miR-29b enhancer region (Figure 5E) through abrogation of Sp1 protein and disruption of Sp1/NFκB DNA binding as confirmed by antibody supershift (Supplemental Figure S4C), thereby closing the miR-29b/Sp1 autoregulatory loop. Interestingly, ectopic expression of a synthetic mature miR-29b in K562 cells resulted in an increase of the miR-29b endogenous precursor (Figure 5F), thereby further supporting miR-29b as an active participant in its own transcriptional regulation.

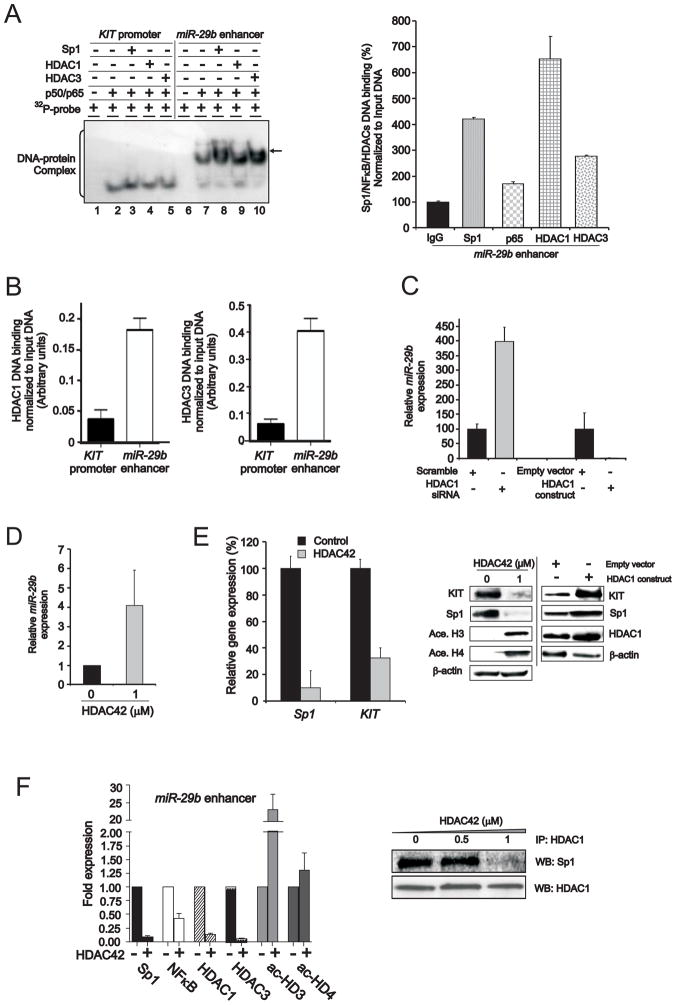

Histone deacetylases contribute to the repressor activity of Sp1/NFκB on miR-29b

Having shown that Sp1/NFκB acts as a repressive complex for miR-29b and as an activating complex for KIT expression, next we asked whether other factors could participate in conferring differentiating regulatory functions to this complex. While Sp1/NFκB is involved in the regulation of DNA hypermethylation (Liu et al., 2008), we observed only few CpG islands and no obvious DNA methylation of the 5′ putative regulatory region of miR-29b in either AML patient samples or cell lines with low expression of this miRNA (Marcucci- unpublished results). Therefore, we postulated that epigenetic mechanisms causing chromatin changes other than DNA hypermethylation could be involved in silencing miR-29b. A number of previous studies showed that Sp1/NFκB physically interacts with histone deacetylases (HDACs) 1 and 3 to repress target gene transcription (Doetzlhofer et al., 1999). Therefore, in order to test whether HDAC1 and 3 associate with Sp1/NFκB to repress miR-29b expression, we incubated 32P-labeled probes designed from the KIT promoter or miR-29b regulatory regions with recombinant NFκBp50/p65 proteins to form a DNA-protein complex (Figure 6A, left panel, lanes 2 to 10). Recombinant Sp1 (Figure 6A, left panel, lanes 3 or 8), HDAC1 (Figure 6A, left panel, lanes 4 or 9) or HDAC3 (Figure 6A, left panel, lanes 5 or 10) proteins were then added. No obvious alterations of the DNA-protein complex were observed in the KIT promoter indicating that HDAC1 and 3 (Figure 6A, lanes 4 and 5) were not part of the Sp1/NFκB complex. In contrast, in the miR-29b regulatory sequence, we observed delayed and more intense bands after the addition of recombinant HDACs (Figure 6A, left panel, lanes 9 and 10) (indicated by arrow) supporting the interaction of HDAC1 and 3 and Sp1/NFκB within the miR-29b regulatory sequence. The enrichment of HDACs and Sp1/NFκB on the miR-29b regulatory sequences was further confirmed by ChIP (Figure 6A, right panel). Preferential HDAC binding on miR-29b with respect to the KIT promoter was also confirmed in Kasumi-1 cells (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. HDACs participate in the Sp1/NFκB complex to inhibit miR-29b expression.

(A) Using recombinant proteins, EMSA (left panel) demonstrated the association of HDACs with Sp1/NFκB on miR-29b regulatory region, which was confirmed by ChIP (right panel) (mean ± SEM). 32P-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides containing Sp1 and NFκB consensus sites from KIT promoter or miR-29b regulatory regions were incubated with recombinant proteins NFκBp50 and p65, and supplemented with recombinant proteins Sp1 (lanes 3 and 8), HDAC1 (lanes 4 or 9) or HDAC3 (lanes 5 or 10). Additional complexes seen only with miR-29b probe were indicated with arrow. In right panel, ChIP assays showed that Sp1/NFκB/HDACs were enriched on miR-29b enhancer.

(B) ChIP assays showed that HDAC1 and 3 had higher DNA binding affinity on miR-29b than KIT regulatory element (mean ± SEM).

(C) miR-29b transcription inversely related to the level of HDAC1 in Kasumi-1 cells transfected with HDAC1 siRNA or everexpression construct (mean ± SEM).

(D) HDAC inhibitor (HDAC42) enhanced miR-29b transcription determined by qRT-PCR (mean ± SEM).

(E) HDAC inhibition by HDAC42 concurrently reduced Sp1 and KIT RNA (left panel) (mean ± SEM) or protein (middle panel) expression in Kasumi-1 cells. Conversely, HDAC1 overexpression increased Sp1 and KIT level (right panel).

(F) HDAC inhibition by HDAC42 abrogated Sp1/NFκB/HDAC repressor complex. In left panel, ChIP assays demonstrated that the disruption of Sp1/NFκB/HDAC complex and the accumulation of acetylated histone H3 (ac-HD3) and H4 (ac-HD4) on miR-29b regulatory region (mean ± SEM). In right panel, co-immunoprecipitation showed that HDAC42 disrupted Sp1/HDAC1 interaction.

Data are representatives of three independent experiments. (See also Figure S5)

The biological function of HDACs in miR-29b regulation was further supported by the observation that HDAC1 siRNA knockout or ectopic expression resulted respectively in higher and lower miR-29b expression (Figure 6C). Accordingly, treatment with the HDAC inhibitor OSU-HDAC42 (Sargeant et al., 2008) resulted in an increase of miR-29b transcription (Figure 6D) with concurrent reduction of both Sp1 and KIT RNA and protein expression (Figure 6E). Similar results were attained with another HDAC inhibitor, MS275 (Supplemental Figure S5). Conversely, ectopic HDAC1 expression resulted in Sp1 and KIT upregulation (Figure 6E). Consistent with these data, we also observed that HDAC inhibitors induced a relative decrease of HDAC1 and 3 enrichment and increase in histone acetylation in the miR-29b enhancer region (Figure 6F, left panel). The decreased binding of HDACs on the miR-29b enhancer region was likely due to the disruption of the Sp1/HDAC physical interaction by the HDAC inhibitors (Figure 6F, right panel).

KIT autoregulatory loop

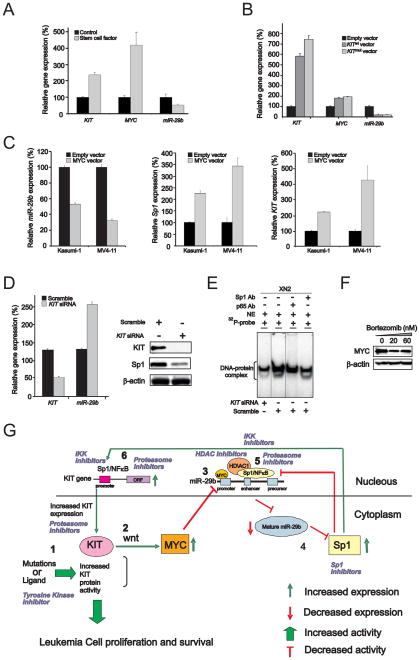

As KIT expression levels are relatively high in cells harboring gain-of-function mutations, we next questioned whether aberrant KIT activation may feedback to regulate its own transcription through the Sp1/NFκB/miR-29b network. Previous studies reported that KITmut induces wnt pathway signaling and MYC expression (Tickenbrock et al., 2008). The latter, in turn, was shown to downregulate miR-29b expression (Chang et al., 2008). Therefore, we postulated that KIT protein activity would drive aberrant KIT gene expression by inducing MYC-dependent miR-29b downregulation. We validated our hypothesis by showing that treatment with KIT ligand resulted in increase in KIT and MYC and decrease in miR-29b in THP-1 cells, which, when unstimulated, express relatively low KIT levels and higher miR-29b levels (Figure 7A). Similarly, overexpression of KITmut or KITwt in THP-1 cells resulted in MYC upregulation and miR-29b downregulation (Figure 7B). Finally, ectopic expression of MYC resulted in downregulation of miR-29b (Figure 7C, left panel) and upregulation of the miR-29b target Sp1 (Figure 7C, middle panel), thereby resulting in higher levels of KIT expression in Kasumi-1 and MV4-11 cells (Figure 7C, right panel).

Figure 7. Role of activated KIT in KIT gene transcription.

(A) Treatment with KIT ligand (stem cell factor) induced KIT and MYC upregulation and miR-29b downregulation in THP-1 cells harboring KITwt (mean ± SEM).

(B) Overexpression of KITmut or KITwt increased MYC expression and decreased miR-29b downregulation in THP-1 cells (mean ± SEM).

(C) MYC overexpression increased KIT and Sp1 transcription and decreased miR-29b expression in KITmut Kasumi-1 and KITwt MV4-11 cells (mean ± SEM).

(D) KIT knockout by siRNA enhanced miR-29b expression leading to Sp1 downregulation in Kasumi-1 cells transfected with KIT siRNA (mean ± SEM).

(E) EMSA demonstrated that siRNA-induced KIT knockout decreased Sp1/NFκB binding affinity on its own promoter. The presence of NFκB and Sp1 in the DNA-protein complexes was demonstrated by the abolishment or reduction of complexes with antibody supershift assay. Note, the inserted lines indicate the reposition of the gel.

(F) MYC protein expression is suppressed in Kasumi-1 cells treated with bortezomib for 24 hours.

(G) Summary diagram describes the Sp1/NFκB/HDAC/miR-29b network that regulates KIT expression. Indicated are also sites of potential therapeutic interventions within the network that may result in the inhibition of KIT expression thereby its activity.

Data (A–F) are representatives of three independent experiments. (See also Figure S6)

To further determine the biologic role of KIT protein abundance, KIT expression was knocked out by siRNA in Kasumi-1 cells. We observed miR-29b upregulation and Sp1 downregulation (Figure 7D), decrease of the Sp1/NFκB complex binding to the KIT promoter as demonstrated by EMSA assays (Figure 7E) and significant antileukemic activity in Kasumi-1 cells (Supplemental Figure S6 A-E). Finally, we demonstrated that bortezomib treatment also led to a decrease in MYC protein expression (Figure 7F). Altogether, these results support that MYC-induced miR-29b downregulation, occurring upon activation of the KIT protein in leukemia cells, leads to the KIT gene overexpression through the Sp1/NFκB/HDAC/miR-29b network. A summary diagram that outlines the above regulatory network is described in Figure 7G.

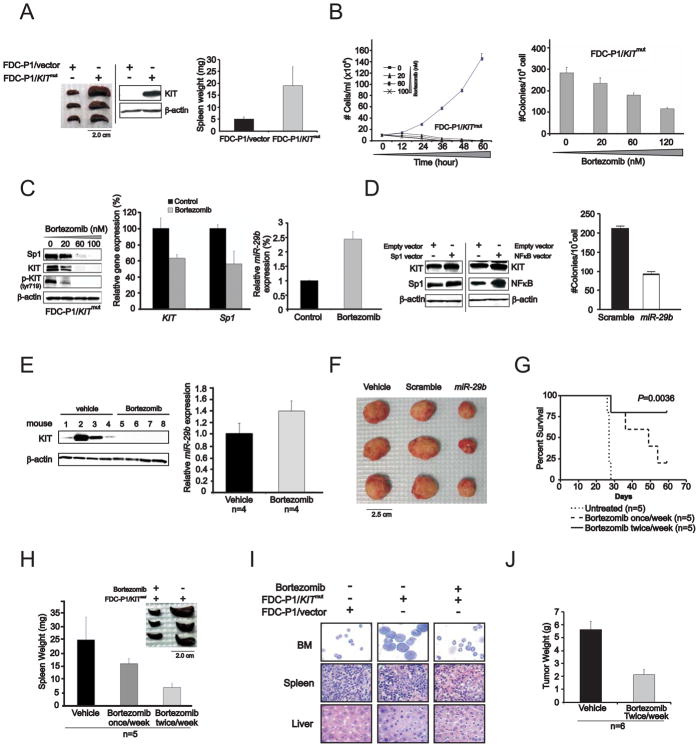

Treatment with bortezomib suppresses in vivo KIT–driven leukemogenesis

Having demonstrated the relevance of the Sp1/NFκB/miR-29b feedback loop on KIT regulation, we next tested whether this loop represented a potentially viable therapeutic target to overcome KIT-driven leukemia in vivo. We cloned D816V KITmut or KITwt into pBABE-puro retroviral vector and stably expressed these constructs in the FDC-P1 cell line, a murine non-tumorigenic diploid cell line derived from myeloid precursors. In in vitro studies, we observed that overexpression of either KITmut or KITwt promoted cell proliferation determined by clonogenic assay, albeit more pronounced effects were attained with KITmut (Supplemental Figure S7A). In order to investigate the leukemic role of KIT protein in vivo, FDC-P1/KITmut cells (5×106/mouse) were then engrafted into NOD/SCID mice, which developed significant splenomegaly (Figure 8A) and died from a leukemia-like illness within 4 weeks. In contrast, no evidence of disease was observed in empty-vector transfected FDC-P1 parental cells. Western blot confirmed KIT expression in the enlarged spleen of FDC-P1/KITmut engrafted mice (Figure 8A).

Figure 8. In vivo activity of bortezomib on KITmut-driven leukemia.

(A) Mice engrafted with FDC-P1/KITmut cells developed leukemia-like disease with enlarged spleens. Left: spleens from mice injected with FDC-P1/KITmut cells; Middle: immunoblotting indicated the presence of human KIT expression in the spleen from the mice engrafted with FDC-P1/KITmut cells, but not in FDC-P1/vector only cells. Right: graph of spleen weight (mean ± SD).

(B) Bortezomib inhibited proliferation (left panel) and colonogenic activity (right panel) in FDC-P1/KITmut cells (mean ± SEM).

(C) Bortezomib treatment decreased Sp1 and KIT protein (left panel) and RNA (middle panel) expression and increased miR-29b level (right panel) (mean ± SEM) in FDC-P1/KITmut cells. (D) Forced Sp1 and NFκB expression in FDC-P1/KITmut cells increased KIT level (left panel) and ectopic miR-29b expression inhibited the colonogenic activity in FDC-P1/KITmut cells (right panel) (mean ± SD). (E) KIT protein expression (left panel) was decreased and miR-29b transcription was increased (right panel) (mean ± SEM) in FDC-P1/KITmut cell engrafted mice 48 hours following in vivo treatment with bortezomib.

(F) Ectopic miR-29b expression significantly inhibits tumor growth in mice engrafted with FDC-P1/KITmut cells transfected with synthetic miR-29b.

(G) Bortezomib administered at the dose of 1mg/kg once a week or twice weekly increased survival duration in mice engrafted with FDC-P1/KITmut cells compared with untreated FDC-P1/KITmut cell engrafted controls.

(H) Spleens from FDC-P1/KITmut cell engrafted mice untreated versus bortezomib-treated (mean ± SD).

(I) May-Grumwald/Giemsa staining of BM cells and H&E staining of sections from spleen and liver of FDC-P1/KITmut cell engrafted mice untreated and bortezomib-treated. FDC-P1/empty vector cell engrafted mice were also used as control.

(J) Tumor growth was inhibited in mice engrafted with HMC-1 cell after the administration of bortezomib (mean ± SD).

Data are representatives of three independent experiments. (See also Figure S7)

Additional in vivo experiments were performed to demonstrate the potential therapeutic relevance of KIT downregulation. We selected bortezomib among the different compounds that we showed to interfere with the Sp1/NFκB/miR-29b regulatory loop, as this compound targets Sp1/NFκB complex, upregulates miR-29b and is an FDA approved anticancer drug. Sp1/NFκB binding sites were found by computational methods (http://www.cbrc.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html) in the promoter region of the pBABE vector carrying KITmut and used to transfect FDC-P1 cells (not shown). In vitro, bortezomib treatment inhibited proliferation (Figure 8B, left panel) and decreased clonogenic activity (Figure 8B, right panel) of FDC-P1/KITmut cells. These effects were associated with Sp1 and KIT protein downregulation, KIT protein hypophosphorylation and miR-29b upregulation (Figure 8C). In contrast, forced Sp1 or NFκB(p65) expression enhanced mutated KIT (Figure 8D, left panel) and ectopic miR-29b expression inhibited colony forming ability in FDC-P1/KITmut cells (Figure 8D, right panel). These findings therefore supported the relevance of the Sp1/NFκB/miR-29b regulatory complex to KIT expression and the pharmacologic activity of bortezomib in FDC-P1/KITmut cells thereby validating FDC-P1/KITmut engrafted mice as a suitable in vivo model for KITmut–driven leukemia. Similar results were also achieved in FDC-P1/KITwt cells exposed to bortezomib (Supplemental Figure S7B and C).

NOD/SCID mice engrafted with FDC-P1/KITmut cells were then treated with one dose bortezomib (1mg/kg/dose) and sacrificed 48 hours later. We observed that bortezomib abrogated KIT mRNA transcription and protein expression and increased miR-29b expression in vivo (Figure 8E). The role of miR-29b upregulation as a potential key step in the therapeutic response of KIT-driven leukemia to bortezomib was further supported by a decreased engraftment efficiency of FDC-P1/KITmut cells transfected with synthetic miR-29b. The size and weight of murine FDC-P1/KITmut tumor from cells pretreated with miR-29b was significantly lower than those of cells pretreated with vehicle alone or scrambled miRNA when measured at day 21 after engraftment (Figure 8F, and Supplemental Figure S7D).

Next, FDC-P1/KITmut–engrafted mice were treated with 1mg/kg of bortezomib once or twice weekly for three weeks, starting at day 21 after engraftment (n=5 mice/group), and then followed longitudinally. Animals treated with bortezomib demonstrated significantly longer periods of survivals than vehicle-treated controls (Figure 8G). Vehicle-treated FDC-P1/KITmut engrafted mice exhibited massive splenomegaly, whereas spleen size and weight of the bortezomib-treated animals were similar to those of age-matched controls (Figure 8H). Cytospins of bone marrow cells and histopathology of spleen and liver sections from FDC-P1/KITmut-engrafted mice treated with vehicle showed extensive infiltration of blast cells. In contrast, cytospins of bone marrow cells and histopathology of spleen and liver from the bortezomib-treated leukemic mice were similar to that of the age-matched control groups (Figure 8I).

To validate these in vivo data in a model where KIT expression is controlled via an endogenous promoter, we next established murine xenografts with the human mastocytosis HMC-1 cell line carrying KITmut. These cells were sensitive in vitro to bortezomib treatment which induced miR-29b upregulation, and Sp1 and KIT downregulation (Supplemental Figure S7E and F). NOD/SCID mice engrafted with 107 of HMC-1 cells subcutaneously received intratumor administration of 1 mg/kg bortezomib twice/week for two weeks starting from when the tumor size approached 20mm3. Significant decrease in tumor size was observed in bortezomib-treated mice when compared to vehicle-treated controls (Figure 8J). Similarly, bortezomib was therapeutically advantageous in mice engrafted with ME-1 cells overexpressing KITwt (Supplemental Figure S7G). Collectively, these results indicate that KIT overexpression significantly contributes to malignant cell proliferation, and targeting KIT abundance through the miRNA-protein network represents a promising therapeutic approach to overcome KIT-driven leukemia.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies revealed that certain human cancers including AML are characterized by aberrant KIT tyrosine kinase activity (Beadling et al., 2008; Went et al., 2004). To date, much effort has been focused on targeting aberrantly activated KIT mutants using TK inhibitors. Although treatment with these compounds can induce clinical responses in both solid tumors and hematologic malignancies harboring KIT mutations (Heinrich et al., 2008), this strategy is complicated by the needs for adjustment of therapy based on individual KIT genotypes and early onset of treatment resistance due to acquired secondary mutations or/and KIT overexpression. Here we show that aberrantly activated KIT protein itself may drive upregulation of the KIT gene, and high KIT expression is an important contributor to malignant cell proliferation and aggressive disease. Our findings therefore support the rationale for therapeutic targeting of KIT abundance to overcome aberrant KIT activity and induce significant antileukemic effects. The current study was designed to investigate mechanisms that regulate KIT expression, so that treatment strategies attacking directly KIT gene deregulators in leukemia can be developed to circumvent the draw-backs encountered with TK inhibitor therapy. Our investigation indeed led to the identification of a Sp1/NFκB/HDAC/miR-29b network that deregulates KIT gene transcription, impacts leukemogenesis and is targetable pharmacologically.

Previous investigations reported that miR-221/222 directly target KIT expression (Felli et al., 2005). Here, we provide the first evidence of an indirect but pivotal role of miR-29b in modulating KIT expression in KITmut leukemia. By using computational analyses we found lack of miR-29b binding sites in KIT mRNA 3′UTR. However, treatment with ectopic miR-29b or compounds that led to increase in endogenous miR-29b resulted in KIT down-regulation. We showed that this was due to an indirect effect on KIT expression mediated by a miR-29b/Sp1 mutual feedback loop. Sp1, a transactivator of the KIT gene, binds to the miR-29b promoter and represses miR-29b expression, while miR-29b blocks Sp1 translation and in turn up-regulates its own transcription. NFκB, a transcription factor that is in part modulated by the 26S proteasome system and is constitutively activated in AML, physically interacts with Sp1 to regulate miR-29b and KIT expression. HDACs confer transcription repressing activity to the Sp1/NFκB complex binding the miR-29b regulatory elements in leukemia cells, but do not participate in the Sp1/NFκB complex that binds and transactivates the KIT promoter. Thus, when miR-29b is aberrantly suppressed by a Sp1/NFκB/HDAC complex in KITmut leukemia, KITmut becomes upregulated thereby contributing to malignant proliferation. But what is the primary event deregulating this miRNA-protein network? We showed that gain-of-function mutations or aberrant ligand-dependent activation of the KIT protein in leukemia cells lead to constitutive MYC upregulation, which is likely to produce the initial step for decreasing miR-29b below a threshold that results in Sp1 increase, aberrantly high level of Sp1/NFκB/HDAC activity and ultimately KIT upregulation. The latter perpetuates autoregulatory loops that minimize miR-29b expression and maximize KIT expression and activation in leukemia cells.

Pharmacologic intervention with synthetic miR-29b oligonucleotides or compounds that inhibit proteasome (bortezomib), NFκB (bay11-7082), Sp1 (mithramycin A) and HDACs (HDAC42), targets the Sp1/NFκB/HDAC complex in leukemia cells and sequentially results in endogenous miR-29b up-regulation, Sp1 downregulation, disruption of the Sp1/NFκB complexes and inhibition of the KIT gene. The net results are KIT down-regulation, inhibition of aberrant TK activity and arrest of leukemia growth. The pivotal role of miR-29b in this miRNA/protein network is supported by up-regulation or downregulation of KIT expression in response to repression of endogenous miR-29b or forced expression of ectopic miR-29b, respectively. This was further confirmed by showing that ectopic miR-29b expression inhibited the colony forming ability and in vivo growth of KIT-driven leukemia cells (FDC-P1/KITmut cells).

Sp1 and NFκB are ubiquitous transcription factors and over-expressed in human malignancies. We and others demonstrated that Sp1 physically interacts with NFκB to enhance target gene transactivation (Hirano et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2008). Here, we showed that, like miR-29b, these two factors are located at a central position within a regulatory network controlling KIT expression. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib effectively interferes with the activity of Sp1/NFκB complex at concentrations (i.e., 60nM) that are achievable in patients treated at the recommended dose of the drug (Quinn et al., 2009) and was then chosen to test the therapeutic relevance of targeting KIT expression in KITmut leukemia. The intended in vivo target for this compound was the Sp1/NFκB/HDAC/miR-29b network. Our data indeed indicated that bortezomib disrupts both Sp1/NFκB and Sp1/NFκB/HDAC complexes thereby resulting in miR-29b upregulation, Sp1 downregulation and inhibition of the KIT gene transactivation. These events ultimately result in strong antileukemic activity and improved survival in NOD/SCID mice that were engrafted with FDC-P1/KITmut cells. Similar results were also attained in mice xenografted with malignant cells overexpressing KIT under the control of an endogenous promoter. Thus bortezomib appears to be a potentially effective treatment for KIT-driven leukemia despite that it is not predicted by computer-modeling to bind to the same KIT enzymatic pocket where interaction with PKC412, imatinib or other tyrosine kinase inhibitor small molecules occurs (not shown).

In conclusion, our investigation has identified a critical regulatory Sp1/NFκB/HDAC/miR-29b network that modulates KIT expression. We show that aberrant activation of KIT results in MYC-dependent miR-29b downregulation and increase in Sp1 expression. The latter interacts with NFκB and HDACs to further inhibit miR-29b expression, and with NFκB alone to transactivate KIT. Because of the central role of Sp1/NFκB complex in mechanisms of KIT dysregulation, proteasome inhibition appears particularly advantageous to target therapeutically this network. Similar pharmacologic effects can be also achieved through inhibition of NFκB (by bay11-7082), Sp1 (by mithramycin A), HDAC1/3 (by HDAC42) or addition of miR-29b. Notably, our previous reports show that miR-29b controls the expression of DNA methyltransferases and restores epigenetically silenced gene expression and cell differentiation patterns in AML blasts displaying DNA hypermethylation (Liu et al., 2008; Garzon et al., 2009). Therefore, therapeutic targeting of the Sp1/NFκB/HDAC/miR-29b network may lead to control not only of KIT, but also of other aberrantly expressed oncogenes (i.e., DNMTs) that, while not directly involved in regulation of KIT expression, may play an equally relevant role in leukemogenesis. Importantly, many of the pharmacologic agents that we have used to target KIT expression are already in the clinic. Thus, we believe that an attractive aspect of our study points to the possibility of rapidly translating our findings into clinical trials targeting molecular subsets of AML in which the Sp1/NFκB/miR-29b network appears to play a central role for oncogene expression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and cell lines

Construction of the human Sp1 in EBV/retroviral hybrid vector and cell culture (Kasumi-1, K562, MV4-11, THP-1) were done as previously reported (Liu et al., 2008). KIT expression plasmids (KITmut and KITwt) were constructed by inserting the KIT gene sequence into pBABE-puro retroviral vector. pCMV-p65 expressing NFκB (p65) and pcDNA3-Flag-HDAC1 expressing HDAC1 (Taunton et al., 1996) were also used. Retroviral infection to establish FDC-P1 cell line stably expressing KITmut or KITwt was performed as previously reported (Neviani et al., 2007).

Cells were treated with the following reagents (concentrations, times and schedules indicated in Results): bortezomib (Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc., Cambridge, MA), MS275, mithramycin A, decitabine and PKC412 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), HDAC-OSU 42 (HDAC42) (OSU, Columbus, OH) (Sargeant et al., 2008) or bay11-7082 (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA).

Patient Samples

Mononuclear cells (MNC) from pretreatment BM samples with >70% of blasts from AML patients with t(8;21) were obtained from the OSU Leukemia Tissue Bank. All patients signed the informed consent for the OSU 1997C0194 protocol to store and use their leukemia tissue for discovery studies. The OSU 1997C0194 protocol was approved by the OSU Cancer Institutional Review Board (IRB) Committee.

Gene expression in AML patients

KIT, Sp1 and miR-29b expression levels were measured in RNA samples of BM MNC from CBF and CN AML patients enrolled on CALGB treatment studies 8525, 9621 and 19808, using the Affymetrix U133 plus 2.0 GeneChips (KIT and Sp1) (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) and OSU microRNA microarray chip as previously reported (Radmacher et al., 2006; Marcucci et al., 2008). For the gene expression microarrays, summary measures of the expression levels were computed for each probe set using the robust multichip average method, which incorporates quantile normalization of arrays (Irizarry et al., 2003). For the microRNA expression microarrays, summary measures of expression levels were computed for each probe using quantile normalization, making an adjustment for array batch (Rao et al., 2008). Samples for analyses were obtained from patients who were enrolled on CALGB clinical studies and signed an informed consent for CALGB 20202 to store and use their leukemia tissue for molecular characterization of AML. The CALGB 20202 protocol was locally approved by the OSU Cancer IRB Committee. All microarray data has been submitted to ArrayExpress (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/microarray-as/ae/) and can be found under the accession number E-TABM-945.

Transient transfection, immunoprecipitation and Western blot

On-targetplus Smart pool SiRNA for Sp1, NF Bp65, KIT and HDAC1 were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Precursor miR-29b was from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Antago-miR-29b was from Exiqon, Inc (Woburn, MA). SiRNA, miRNA oligos or plasmid constructs were introduced into leukemia cell lines by Nucleofector Kit (Lonza Walkerrsville Inc, Walkersville, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The immunoprecipitation and Western blots were preformed as previously described (Liu et al., 2008). The antibodies used were: Sp1, total KIT, p-tyrosine, p-ERK (tyr 204) and β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); phospho-KIT (tyr719), phospho-p65 (Ser536), phospho-IKBα (Ser32), phospho-Stat3 (Tyr705), phospho-Stat1 (tyr701), phospho-Stat5 (ser694), phosphor-Akt, total Akt, total Erk, total Stat1, total Stat3, and total Stat5 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); ubiquitin (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Electrophoretic mobility-shift assays (EMSA)

EMSA with nuclear extracts and 32P-labeled probes were performed as described (Hong et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2008). The primers for KIT and miR-29b promoter were listed in supplementary material. Recombinant proteins, NFκB(p50) and Sp1 (Promega, Madison, WI), NFκB(p65) and HDAC1 and HDAC3 (Caymanchem, Ann Arbor, MI), were purchased.

Real-Time RT-PCR

For normalized expression of KIT, MYC and Sp1, qRT-PCR was performed as described (Marcucci et al., 2005). For miRNA expression, qRT-PCR was carried out by TaqMan MicroRNA Assays (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and normalized by U44/48 (for human) or Sno202 (for mouse) levels. Expression of the target genes were measured using the ΔCT approach.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP assays were performed using the EZ ChIP Assay Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer’s standard protocol. DNA was quantified using qRT-PCR with SYBR green incorporation (Applied Biosystems). The antibodies used were: anti-acetyl-histone H4, acetyl-histone H3, HDAC1, HDAC3, Sp1, and NFκB(p65) (Millipore). The primers specific for KIT gene promoter or miR-29b enhancer were listed in supplementary material.

Leukemogenesis in NOD/SCID mice

Four to six-week-old NOD/SCID (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were i.v. injected through the tail vein with 5×106 cells of FDC-P1 cells harboring D816V KITmut. After engraftment, cell-injected mice (n=5) were i.v. treated with 1mg/kg of bortezomib via tail-vein in 0.2 ml of saline solution once or twice a week. Longitudinal follow-up to assess survival was conducted and the trial was terminated 8.5 weeks after injection. Mice injected with FDC-P1/KITmut cells (n=5) and injected with saline solution only served as controls. The effect of bortezomib on targets (KIT and miR-29b) was tested in vivo in FDC-P1/KITmut-engrafted mice (n=4) treated with 1mg/kg of bortezomib and assessed for KIT and miR-29b expression 48 hours following drug administration. Following euthanasia, isolated spleens were grounded, and the red blood cells were lysed to attain single MNCs utilized for immunoblotting and qRT-PCR assays. For pathological examination, tissue sections from liver and spleen were fixed on formalin, embedded in paraffin blocks and H&E stained. The effect of a synthetic miR-29b engraftment ability of FDC-P1/KITmut was tested by engrafting FDC-P1/KITmut cells transfected with miR-29b, scrambled miRNA or vehicle. The transfection efficiency of the miRNA compounds was approximately 50–60% as evaluated by concurrent transfection of a plasmid expressing GFP.

Finally, NOD/SCID mice were also injected with 107 HMC-1 or ME-1 cells subcutaneously. When tumor size approached approximately 20mm3, the animals received 1mg/kg of bortezomib or vehicle alone twice a week (intravenous bolus) for two weeks. The experiments were terminated in two weeks after drug administration. All animal studies were performed in accordance with OSU institutional guidelines for animal care and under approved protocols (OSU 2007A0149 and 2008A0027) by the OSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses relative to microarray gene and microRNA expression data were performed by the CALGB Statistical Center.

SIGNIFICANCE.

KIT encodes a tyrosine kinase receptor that activates downstream pathways leading to cell proliferation and survival. Overexpression of mutated or wild-type KIT alleles occurs in specific subsets of AML and predicts poor outcome, thereby supporting a critical role of high levels of the KIT protein in leukemogenesis. Here we report deregulation of a protein-microRNA network, Sp1/NFκB/HDAC/miR-29b that results in KIT overexpression in KIT-driven leukemia. We also show that this network is targetable by proteasome, NFκB, Sp1 or HDAC inhibitors or ectopic miR-29b expression. These compounds provide antileukemic activity by decreasing KIT expression through miR-29b-dependent Sp1 downregulation, and represent promising therapeutic approaches to disrupt KIT expression and efficiently override aberrant KIT activity in KIT-driven AML.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD), grants CA102031, CA077658, CA101140, CA140158, CA114725, and the Coleman Leukemia Research Foundation, the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Research Foundation and the Deutsche Krebshilfe (Dr. Mildred Scheel Foundation for Cancer Research). We thank Dr. Clara Nervi for providing SKNO-1 cell line, and J. Kearney-Bryan and Drs. R. Klisovic and Zhongfa Liu for their technical support.

Footnotes

Accession Numbers

The microarray data discussed in this study have been deposited in the EBI ArrayExpress database and are accessible at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/microarray-as/ae/under Array Express accession number: E-TABM-945.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bargou RC, Emmerich F, Krappmann D, Bommert K, Mapara MY, Arnold W, Royer HD, Grinstein E, Greiner A, Scheidereit C, Dorken B. Constitutive nuclear factor-kappaB-RelA activation is required for proliferation and survival of Hodgkin’s disease tumor cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2961–2969. doi: 10.1172/JCI119849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beadling C, Jacobson-Dunlop E, Hodi FS, Le C, Warrick A, Patterson J, Town A, Harlow A, Cruz F, 3rd, Azar S, et al. KIT gene mutations and copy number in melanoma subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6821–6828. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TC, Yu D, Lee YS, Wentzel EA, Arking DE, West KM, Dang CV, Thomas-Tikhonenko A, Mendell JT. Widespread microRNA repression by Myc contributes to tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:43–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetzlhofer A, Rotheneder H, Lagger G, Koranda M, Kurtev V, Brosch G, Wintersberger E, Seiser C. Histone deacetylase 1 can repress transcription by binding to Sp1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5504–5511. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felli N, Fontana L, Pelosi E, Botta R, Bonci D, Facchiano F, Liuzzi F, Lulli V, Morsilli O, Santoro S, et al. MicroRNAs 221 and 222 inhibit normal erythropoiesis and erythroleukemic cell growth via kit receptor down-modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18081–18086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506216102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajiwala KS, Wu JC, Christensen J, Deshmukh GD, Diehl W, DiNitto JP, English JM, Greig MJ, He YA, Jacques SL, et al. KIT kinase mutants show unique mechanisms of drug resistance to imatinib and sunitinib in gastrointestinal stromal tumor patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1542–1547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812413106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartel AL, Ye X, Goufman E, Shianov P, Hay N, Najmabadi F, Tyner AL. Myc represses the p21(WAF1/CIP1) promoter and interacts with Sp1/Sp3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4510–4515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081074898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon R, Liu S, Fabbri M, Liu Z, Heaphy CE, Callegari E, Schwind S, Pang J, Yu J, Muthusamy N, et al. MicroRNA-29b induces global DNA hypomethylation and tumor suppressor gene re-expression in acute myeloid leukemia by targeting directly DNMT3A and 3B and indirectly DNMT1. Blood. 2009;113:6411–6418. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Growney JD, Clark JJ, Adelsperger J, Stone R, Fabbro D, Griffin JD, Gilliland DG. Activation mutations of human c-KIT resistant to imatinib mesylate are sensitive to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor PKC412. Blood. 2005;106:721–724. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich MC, Blanke CD, Druker BJ, Corless CL. Inhibition of KIT tyrosine kinase activity: a novel molecular approach to the treatment of KIT-positive malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1692–1703. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hideshima T, Ikeda H, Chauhan D, Okawa Y, Raje N, Podar K, Mitsiades C, Munshi NC, Richardson PG, Carrasco RD, Anderson KC. Bortezomib induces canonical nuclear factor-kappaB activation in multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2009;114:1046–1052. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-199604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano F, Tanaka H, Hirano Y, Hiramoto M, Handa H, Makino I, Scheidereit C. Functional Interference of Sp1 and NF-B through the Same DNA Binding Site. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1266–1274. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JW, Allen CE, Wu LC. Inhibition of NF-kappaB by ZAS3, a zinc-finger protein that also binds to the kappaB motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12301–12306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133048100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Kanakura Y, Tamaki T, Kuriu A, Kitayama H, Ishikawa J, Kanayama Y, Yonezawa T, Tarui S, Griffin JD. Expression and functional role of the proto-oncogene c-kit in acute myeloblastic leukemia cells. Blood. 1991;78:2962–2968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003 Feb 15;31(4):e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Yamamoto Y, Wang QM. The IKK NF-kappa B system: a treasure trove for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:17–26. doi: 10.1038/nrd1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski M, Larose L, Lee F, Le DM, Rottapel R, Siminovitch KA. SHP-1 binds and negatively modulates the c-Kit receptor by interaction with tyrosine 569 in the c-Kit juxtamembrane domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2089–2099. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Liu Z, Xie Z, Pang J, Yu J, Lehmann E, Huynh L, Vukosavljevic T, Takeki M, Klisovic RB, et al. Bortezomib induces DNA hypomethylation and silenced gene transcription by interfering with Sp1/NF-kappaB-dependent DNA methyltransferase activity in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:2364–2373. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-110171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcucci G, Baldus CD, Ruppert AS, Radmacher MD, Mrozek K, Whitman SP, Kolitz JE, Edwards CG, Vardiman JW, Powell BL, et al. Overexpression of the ETS-related gene, ERG, predicts a worse outcome in acute myeloid leukemia with normal karyotype: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9234–9242. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcucci G, Radmacher MD, Maharry K, Mrózek K, Ruppert AS, Paschka P, Vukosavljevic T, Whitman SP, Baldus CD, Langer C, Liu CG, Carroll AJ, Powell BL, Garzon R, Croce CM, Kolitz JE, Caligiuri MA, Larson RA, Bloomfield CD. MicroRNA expression in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2008 May 1;358(18):1919–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson K, Heiss E, Band H, Ronnstrand L. Direct binding of Cbl to Tyr568 and Tyr936 of the stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit is required for ligand-induced ubiquitination, internalization and degradation. Biochem J. 2006;399:59–67. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa K, Toyama K, Gotoh A, Hendrie PC, Mantel C, Broxmeyer HE. Ligand-dependent polyubiquitination of c-kit gene product: a possible mechanism of receptor down modulation in M07e cells. Blood. 1994;83:137–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori N, Fujii M, Iwai K, Ikeda S, Yamasaki Y, Hata T, Yamada Y, Tanaka Y, Tomonaga M, Yamamoto N. Constitutive activation of transcription factor AP-1 in primary adult T-cell leukemia cells. Blood. 2000;95:3915–3921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neviani P, Santhanam R, Oaks JJ, Eiring AM, Notari M, Blaser BW, Liu S, Trotta R, Muthusamy N, Gambacorti-Passerini C, et al. FTY720, a new alternative for treating blast crisis chronic myelogenous leukemia and Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2408–2421. doi: 10.1172/JCI31095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano M, Tam SW, Theodoras AM, Beer-Romero P, Del Sal G, Chau V, Yew PR, Draetta GF, Rolfe M. Role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in regulating abundance of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27. Science. 1995;269:682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.7624798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschka P, Marcucci G, Ruppert AS, Mrozek K, Chen H, Kittles RA, Vukosavljevic T, Perrotti D, Vardiman JW, Carroll AJ, et al. Adverse prognostic significance of KIT mutations in adult acute myeloid leukemia with inv(16) and t(8;21): a Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3904–3911. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DI, Nemunaitis J, Fuloria J, Britten CD, Gabrail N, Yee L, Acharya M, Chan K, Cohen N, Dudov A. Effect of the cytochrome P450 2C19 inhibitor omeprazole on the pharmacokinetics and safety profile of bortezomib in patients with advanced solid tumours, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or multiple myeloma. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48:199–209. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200948030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radmacher MD, Marcucci G, Ruppert AS, Mrozek K, Whitman SP, Vardiman JW, Paschka P, Vukosavljevic T, Baldus CD, Kolitz JE, et al. Independent confirmation of a prognostic gene-expression signature in adult acute myeloid leukemia with a normal karyotype: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Blood. 2006;108:1677–1683. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao Y, Lee Y, Jarjoura D, Ruppert AS, Liu CG, Hsu JC, Hagan JP. A comparison of normalization techniques for microRNA microarray data. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2008;7(1) doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1287. Article22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray R, Snyder RC, Thomas S, Koller CA, Miller DM. Mithramycin blocks protein binding and function of the SV40 early promoter. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:2003–2007. doi: 10.1172/JCI114110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambol EB, Ambrosini G, Geha RC, Kennealey PT, Decarolis P, O’Connor R, Wu YV, Motwani M, Chen JH, Schwartz GK, Singer S. Flavopiridol targets c-KIT transcription and induces apoptosis in gastrointestinal stromal tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5858–5866. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant AM, Rengel RC, Kulp SK, Klein RD, Clinton SK, Wang YC, Chen CS. OSU-HDAC42, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, blocks prostate tumor progression in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate model. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3999–4009. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2000;103:211–225. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taunton J, Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. A mammalian histone deacetylase related to the yeast transcriptional regulator Rpd3p. Science. 1996;272:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tickenbrock L, Hehn S, Sargin B, Evers G, Ng PR, Choudhary C, Berdel WE, Muller-Tidow C, Serve H. Activation of Wnt signaling in cKit-ITD mediated transformation and imatinib sensitivity in acute myeloid leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2008;88:174–180. doi: 10.1007/s12185-008-0141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang J, Zhu Jun, Oudenaarden A. MicroRNA-Mediated Feedback and Feedforward Loops Are Recurrent Network Motifs in Mammals. Molecular Cell. 2007;26(5):753–767. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Went PT, Dirnhofer S, Bundi M, Mirlacher M, Schraml P, Mangialaio S, Dimitrijevic S, Kononen J, Lugli A, Simon R, Sauter G. Prevalence of KIT expression in human tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4514–4522. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarden Y, Kuang WJ, Yang-Feng T, Coussens L, Munemitsu S, Dull TJ, Chen E, Schlessinger J, Francke U, Ullrich A. Human proto-oncogene c-kit: a new cell surface receptor tyrosine kinase for an unidentified ligand. Embo J. 1987;6:3341–3351. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee NS, Langen H, Besmer P. Mechanism of kit ligand, phorbol ester, and calcium-induced down-regulation of c-kit receptors in mast cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14189–14201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.