Abstract

Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells can be generated from somatic cells by introduction of Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc, in mouse1-4 and human5-8. Efficiency of this process, however, is low9. Pluripotency can be induced without c-Myc, but with even lower efficiency10,11. A p53 siRNA was recently shown to promote human iPS cell generation12, but specificity and mechanisms remain to be determined. Here we report that up to 10% of transduced mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) lacking p53 became iPS cells, even without the Myc retrovirus. The p53 deletion also promoted induction of integration-free mouse iPS cells with plasmid transfection. Furthermore, in the p53-null background, iPS cells were generated from terminally differentiated T lymphocytes. Suppression of p53 also increased the efficiency of human iPS cell generation. DNA microarray analyses identified 34 p53-regulated genes that are common in mouse and human fibroblasts. Functional analyses of these genes demonstrate that the p53-p21 pathway serves as a safeguard not only in tumorigenicity, but also in iPS cell generation.

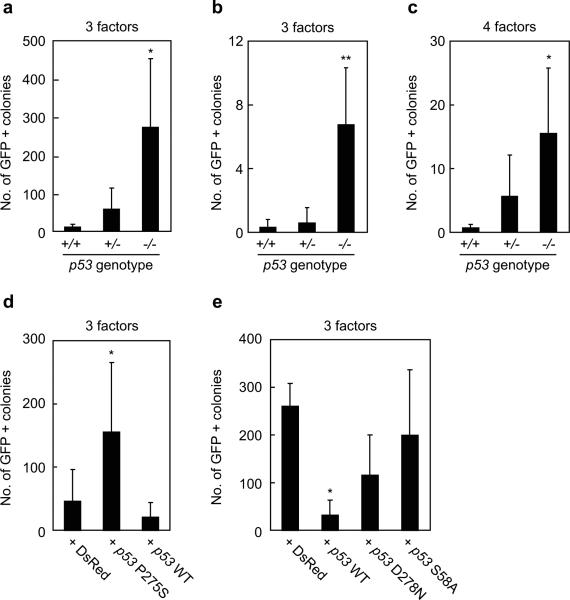

We used the Nanog-GFP reporter system for sensitive and specific identification of iPS cells3. When the three factors devoid of c-Myc were introduced into Nanog-GFP, p53-wild-type MEF, we obtained 11 ± 8 (n=4) GFP-positive colonies from 5000 transduced fibroblasts (Figure 1a). From Nanog-GFP, p53-heterozygous mutant MEF, we observed 58 ± 56 GFP-positive colonies. In contrast, from Nanog-GFP, p53-null fibroblasts, we obtained significantly more GFP-positive colonies (275 ± 181) than from wild-type MEF.

Figure 1. iPS cell generation from p53-null MEF by four or three reprogramming factors.

a. iPS cells were generated from Nanog-GFP reporter MEF, which were either p53 wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/-), or homozygous (-/-), by the three reprogramming factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4). After retroviral transduction, 5000 live cells were collected by a flow cytometer. GFP-positive colonies were counted 28 days after the transduction. *, p<0.05 compared to wild-type (n=4).

b. iPS cells were generated by the three factors from single sorted cells in wells of 96-well plates. GFP-positive colonies were counted 28 days after the transduction. **, p<0.01 compared to wild-type (n=4).

c. iPS cells were generated by the four factors, including c-Myc, from single sorted cells in wells of 96-well plates. GFP-positive colonies were counted 21 days after the transduction. *, p<0.05 compared to wild-type (n=4).

d. Retroviruses expressing either the dominant negative p53 mutant (P275S) or wild-type were co-transduced with the three factors into Nanog-GFP, p53 heterozygous MEFs. After retroviral transduction, 5000 cells were collected and GFP-positive colonies were counted 28 days after the transduction. As a control, retrovirus for a red fluorescent protein (DsRed) was transduced. *, p<0.05 compared to DsRed control (n=3).

e. Retroviruses expressing either the wild-type or mutant p53 were co-transduced with the three factors into Nanog-GFP, p53-null MEFs. After retroviral transduction, 5000 live cells were collected and GFP-positive colonies were counted 28 days after the transduction. *, p<0.05 compared to DsRed control (n=3).

By using a flow cytometer, we plated one Nanog-GFP cell (p53 wild-type, heterozygous mutant, or homozygous mutant), which was transduced with the three factors five days before the re-plating, into a well of 96-well plates. Twenty-three days after the re-plating, we observed GFP-positive colonies in few wells per a 96-well plate with p53 wild-type or heterozygous fibroblasts (Figure 1b). By contrast, we observed GFP-positive colonies in 7 ± 4 (n=4) wells per 96-well plate with p53-null fibroblasts. These data showed that loss of p53 function significantly increased the efficiency and that up to 10% of transduced cells can become iPS cells even without c-Myc.

We performed the same experiment with the four factors, including c-Myc. We observed GFP-positive colonies in zero or one well per a 96-well plate with p53 wild-type fibroblasts (Figure 1c). By contrast, we observed GFP-positive colonies in 6 ± 7 and 16 ± 10 (n=4) wells per a 96-well plate with p53-heterozyous and p53-null fibroblasts, respectively. These data showed that addition of the Myc retrovirus further increased the efficiency of iPS generation up to 20%.

We also tested the effect of a dominant negative p53 mutant P275S13 on the generation of iPS cells. When P275S was introduced into Nanog-GFP, p53-heterozygous MEF, we observed a substantial increase in the number of GFP-positive colonies (Figure 1d). In addition, we placed complementary DNAs (cDNA) encoding the wild-type p53 or transactivation-deficient mutants (D278N14 or S58A15) into the pMXs retroviral vector16 and introduced it together with the retroviruses encoding Oct3/4, Sox2 and Klf4 into Nanog-GFP, p53-null MEFs. Wild-type p53 significantly decreased the number of GFP-positive colonies (Figure 1e). The transactivation-deficient p53 mutants, in contrast, did not show significant effects. These data confirmed that loss of p53 is responsible for the observed increase in the efficiency of direct reprogramming.

We expanded p53-null, GFP-positive clones generated by the three or four factors (six and three clones, respectively). All the clones showed morphology similar to that of mouse ES cells at passage two (S-Figure 1a). Clones generated by the three factors expressed endogenous Oct3/4, endogenous Sox2, and Nanog at comparable levels to those in ES cells (S-Figure 1b). The total expression levels of Oct3/4 and Sox2 were also comparable to those in ES cells, indicating that transgenes were effectively silenced (S-Figure 1c). When transplanted into nude mice, all the six clones gave rise to teratomas containing tissues derived from the three germ layers (S-Figure 1d). These data confirmed pluripotency of iPS cells generated by the three factors from p53-null MEFs.

We found that the expressions of the endogenous Oct3/4 and Sox2 were low in p53-null cells generated by the four factors including c-Myc. (S-Figure 1b). In contrast, the total expression levels of Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc were markedly higher in these cells than in the remaining iPS cells and ES cells (S-Figure 1c), indicating that retroviral expression remained active in these cells. Consistent with this observation, tumors derived from these cells in nude mice largely consisted of undifferentiated cells, with only small areas of differentiated tissues (S-Figure 1d). Furthermore, the p53-null cells generated by the four factors were not able to maintain ES cell-like morphology after passage five (S-Figure 1e). Thus the c-Myc transgene, in the p53-null background, suppresses retroviral silencing and inhibits acquirement and maintenance of iPS cell identity.

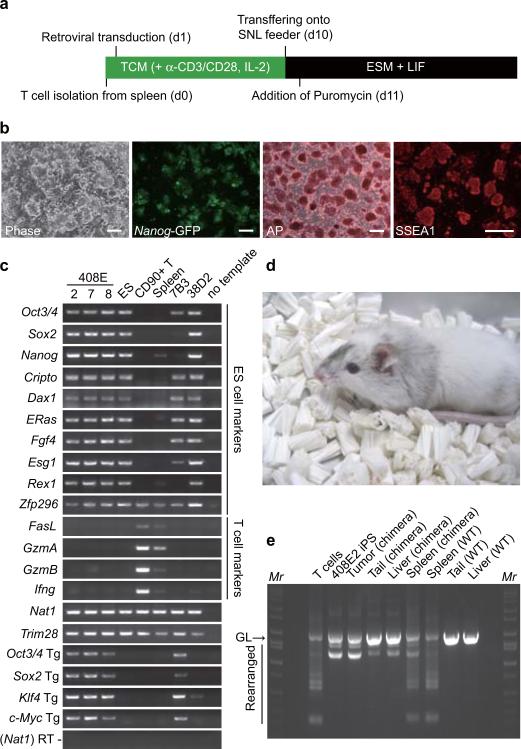

We next tried to generate iPS cells from terminally differentiated somatic cells by the four factors in a p53-null background (Figure 2a). We isolated T lymphocytes from Nanog-GFP reporter mice that were either p53 wild-type or p53-null. We activated T cells by anti-CD3/CD28 antibody and transduced with the four retroviruses. From p53 wild-type T lymphocytes, we did not obtain any GFP-positive colonies. In contrast, we obtained 11 GFP-positive colonies from p53-null T cells (2 × 106 cells), from which three iPS cell lines were established.

Figure 2. T-lymphocyte-derived iPS cells.

a. Protocol for iPS cell generation from mouse T-lymphocytes. TCM; T cell medium, ESM; ES cell medium.

b. A phase contrast image, Nanog-GFP expression, alkaline phosphatase staining, and SSEA1 staining of T cell-derived iPS cells (clone 408E2). Bars indicate 100 μm.

c. Expression of marker genes was examined by RT-PCR in T cell-derived iPS cells (clones 408E -2, -7 and -8), RF8 ES cells, T cells, Spleen, Fbx15-selected iPS cells from p53 wild-type MEF (clone 7B3), and Nanog-selected iPS cells from p53 wild-type MEF (clone 38D2)

d. A chimera mouse derived from clone 408E2. iPS cells were microinjected into blastocysts from ICR mice.

e. The V-(D)-J DNA rearrangement of the Tcrβ gene was confirmed by genomic PCR in iPS cells and a chimeric mouse. GL indicates the germline band.

These GFP-positive cells were expandable and showed morphology similar to that of mouse ES cells (Figure 2b). They were positive for alkaline phosphatase and SSEA1, makers of mouse ES cells (Figure 2b). They also expressed ES cell marker genes, including Rex1, and Nanog (Figure 2c). In contrast, they did not express T cell specific genes such as FasL, GzmA, GzmB and Ifng. As was the case in iPS cells derived from p53-null MEF, silencing of the transgenes in these cells was not complete. Nevertheless, we obtained four adult chimeric mice from these iPS cells (Figure 2d). As we predicted from the p53-null background and incomplete silencing of the c-Myc retroviruses, three of the four chimeric mice died within seven weeks. We confirmed the rearrangement of the T cell receptors in these iPS cells, various tissues from the chimeras, and the tumor observed in the chimeras (Figure 2e). The intensity of the rearranged bands in tumors was as strong as in iPS cells, indicating that the tumor was derived from iPS cells. These data demonstrated that the four factors could generate iPS cells even from terminally differentiated T cells, when p53 is inactivated.

We then examined whether p53 deficiency increased efficiency of human iPS cell generation. To this end, we introduced the dominant negative mutant P275S or a p53 carboxy-terminal dominant-negative fragment (p53DD)17 into adult human dermal fibroblasts (HDF) together with three or four reprogramming factors. We found that the numbers of iPS cell colonies markedly increased with the two independent p53 dominant negative mutants (S-Figure 2a & b). In another experiment, we examined effects of shRNA against human p53 (shRNA-2)18. We confirmed that the shRNA effectively suppressed the p53 protein level (S-Figure 2c) in HDF. When co-introduced with the four reprogramming factors, the p53 shRNA markedly increased the number of human iPS cell colonies (S-Figure 2d). Similar results were obtained in the experiments with three reprogramming factors (S-Figure 2e). In contrast, suppression of Rb did not enhance iPS cell generation. A control shRNA containing one nucleotide deletion in the antisense sequence (shRNA-1) did not show such effects (S-Figure 2d & e). Co-introduction of the mouse p53 suppressed the effect of the shRNA. When transplanted into testes of SCID mice, these cells developed teratomas containing various tissues of three germ layers (S-Figure 2f). These data demonstrated that p53 suppresses iPS cell generation not only in mice, but also in human.

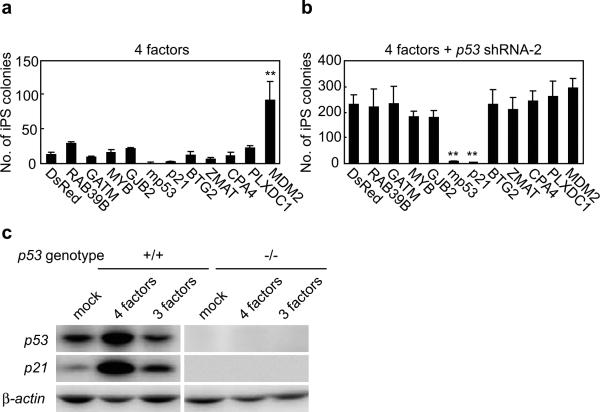

To elucidate p53 target genes that are responsible for the observed enhancement of iPS cell generation, we compared gene expression between p53 wild-type MEF and p53-null MEF by DNA microarrays, and between control HDF and p53 knockdown HDF. In MEF, 1590 genes increased and 1485 genes decreased >5 fold in p53-null MEF. In HDF, 290 genes increased and 430 genes decreased >5 fold by p53 shRNA. Between mouse and human, eight increased genes are common, including v-myb myeloblastosis viral oncogene homolog (MYB) and a RAS oncogenes family, RAB39B (S-Table 1). Twenty-seven decreased genes were common between the two species, including p53, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21, Cip1), BTG family, member 2 (BTG2), zinc finger, matrin type 3 (ZMAT3), and MDM2.

We transduced four increased genes and seven decreased genes by retroviruses into HDF, together with either the four reprogramming factors alone, or with the four factors and the p53 shRNA. Among the four increased genes, none mimicked the effect of p53 suppression (Figure 3a). Among seven decreased genes, MDM2, which binds to and degrades the p53 proteins, mimicked p53 suppression. Two genes, p53 derived from mouse, and p21 effectively counteracted the effect of the p53 shRNA (Figure 3b). Forced expression of p21 markedly decreased iPS cell generation from p53-null MEF (not shown). In wild-type MEF, the combination of the four factors markedly increased p21 protein levels (Figure 3c). When c-Myc was omitted, p21 proteins still increased, but to a lesser extent than with the four factors. In p53-null MEF, these increases of p21 proteins by either the three or four factors were not observed. These data highlighted importance of p21 as a p53 target during iPS cell generation.

Figure 3. Effect of c-Myc and p53 suppression on p21.

a. Genes regulated by p53 were introduced into HDFs together with the four reprogramming factors. On day 24 post-transduction, numbers of iPS cell colonies were counted. **; p<0.01 compared to DsRed control (n=3).

b. Genes regulated by p53 were introduced into HDFs together with the four reprogramming factors and the p53 shRNA. On day 28 post-transduction, numbers of iPS cell colonies were counted. **; p<0.01 compared to DsRed control (n=3).

c. Induction of p21 proteins during iPS cell generation. MEFs, either wild-type or p53-null, were tranduced with the four or three reprogramming factors. Three days after the transduction, protein levels of p21 and p53 were determined by western blot analyses.

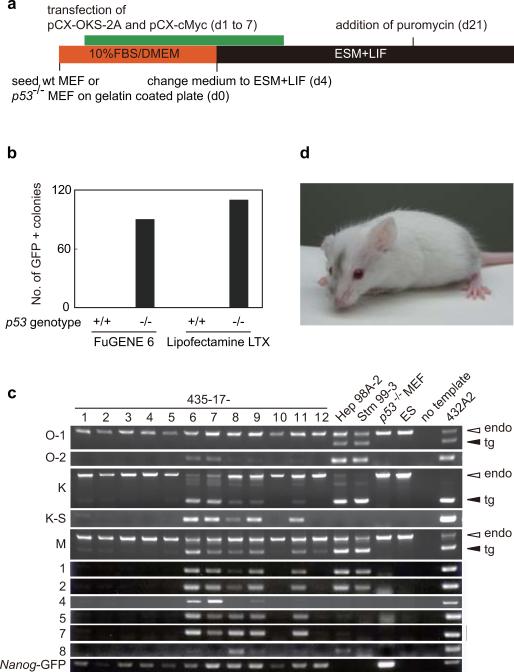

Finally, we generated iPS cells from wild-type or p53-null MEF, both containing the Nanog-GFP reporter, by repeated trasnfection of two expression plasmids, one containing the cDNAs of Oct3/4, Klf4, and Sox2 connected with the 2A polypeptides and the other one with the c-Myc cDNA (Figure 4a). We plated 1.3 × 105 MEF and transfected the two plasmids together daily for seven days. On 28th days after the initial transfection, we did not observe any Nanog-GFP positive colonies from wild-type cells (Figure 4b). In contrast, ~100 GFP-positive colonies emerged from p53-null cells. We randomly picked up 12 colonies and found that seven of them did not contain plasmid integrations (Figure 4c). By microinjecting these integration-free iPS cells, we obtained adult chimeric mice (Figure 4d). It remains to be determined whether germline transmission can be obtained.

Figure 4. Effect of p53 suppression on plasmid-mediated mouse iPS cell generation.

a. Protocol for mouse iPS cell generation by plasmid transfection.

b. Number of GFP-positive colonies. Shown are results of experiment with different transfection reagents.

c. Detection of plasmid integration by genomic PCR.

d. A chimera mouse derived from integration-free iPS cells. iPS cells were microinjected into blastocysts from ICR mice.

Our data showed that p53 and p21 suppress iPS cell generation. Suppressive effects of these tumor suppressor gene products on cell proliferation, survival, or plating efficiency should contribute to the observed effect (S-figure 3). In addition, they may have direct effects on reprogramming. Permanent suppression of p53 would lower quality of iPS cells and cause genomic instability. Nevertheless, transient suppression of p53 by siRNA or other methods may be useful in generating integration-free iPS cells for future medical applications.

METHODS SUMMARY

Effect of p53 suppression in iPS cell generation

Mice deficient in p53 (Taconic Farms, Inc) crossed with Nanog-GFP reporter mice3. HDF from facial dermis of 36-year-old Caucasian female was purchased from Cell Application, Inc. Generation and analyses of mouse iPS cells with retroviruses was performed as previously described3,10,19. Human iPS cells were generated and evaluated as described5. Various p53 mutants were constructed as described in Method. Retroviral vectors for shRNA were purchased from Addgene. The p53 mutants and shRNAs were co-transduced with the reprogramming factors.

Microarray analyses

Total RNAs were analyzed with oligonucleotide microarrays (Agilent) and GeneSpring software (Agilent). Microarray data are available from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with the accession number GSE13365.

Generation of integration-free mouse iPS cells from p53-null MEF by plasmid transfection

Generation of integration-free mouse iPS cells was performed as previously described20, with some modifications. Briefly, wild type or p53-/- Nanog-GFP MEFs were seeded at 1.3 × 105 cells per well of gelatin-coated 6-well plates (day 0). Co-transfection of pCX-OKS-2A and pCX-cMyc using FuGENE6 (Roche) or Lipofectamine LTX (with plus reagent) (Invitrogen) was done once a day from the day 1 to day 7. The cells were cultivated with ES medium containing LIF from day 4. From day 21, puromycin (1.5 μg ml-1) was added into the medium. On day 34, several GFP-positive colonies were picked up for expansion. Integration of plasmids into host chromosomes were examined with genomic PCR20.

Statistical analyses

Data are shown in averages ± standard deviations. Statistical analyses were performed with One-Way Repeated-Measures ANOVA and Bonferroni Post Hoc test, by using KaleidaGraph 4 (HULINKS, Japan).

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Srivastava for critical reading of the manuscript; M. Narita, A. Okada, N. Takizawa, H. Miyachi and S. Kitano for technical assistance; and R. Kato, S. Takeshima, Y. Ohtsu, and E. Nishikawa for administrative assistance. We also thank Y. Sasai and T. Tada for technical advices, T. Kitamura for Plat-E cells and pMXs retroviral vectors, R. Farese for RF8 ES cells, and B. Weinberg and W. Hahn for shRNA constructs. This study was supported in part by a grant from the Leading Project of MEXT, Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research of JSPS and MEXT, and a grant from the Program for Promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of NIBIO (to S.Y.). H. H. is a research student under the Japanese Government (MEXT).

METHODS

Generation of p53 retroviral vectors

cDNA of mouse p53 gene was amplified by RT-PCR with p53-1S (CAC CAG GAT GAC TGC CAT GGA GGA GTC) and p53-1223AS (GTG TCT CAG CCC TGA AGT CAT AA), and subcloned into pENTR-D-TOPO (Invitrogen). After sequencing verification, cDNA was transferred to pMXs-gw by Gateway cloning technology (Invitrogen). Retroviral vectors for p53 mutants were generated by two-step PCR. For the P275S mutant, the first PCR was performed with two primer sets, p53-P275S-S (TGT TTG TGC CTG CTC TGG GAG AGA CCG C) and p53-1223AS, and p53-P275S-AS (GCG GTC TCT CCC AGA GCA GGC ACA AAC A) and p53-1S. For the DD mutant, the first PCR was performed with two primer sets, p53-DD-S (CGG ATA TCA GCC TCA AGA GAG CGC TGC C) and p53-1223AS, and p53-DD-AS (GGC AGC GCT CTC TTG AGG CTG ATA TCC G) and p53-1S. For the D278N mutant, the first PCR was performed with two primer sets, p53-D278N-S (TGC CCT GGG AGA AAC CGC CGT ACA GAA) and p53-1223AS, and p53-D278N-AS (TTC TGT ACG GCG GTT TCT CCC AGG GCA) and p53-1S. For the S58A mutant, the first PCR was performed with two primer sets, p53-S58A-S (TTT GAA GGC CCA GCT GAA GCC CTC CGA) and p53-1223AS, and p53-S58A-AS (TCG GAG GGC TTC AGC TGG GCC TTC AAA) and p53-1S. The two PCR products of each first PCR were mixed and used as a template for the secondary PCR with the primer set, p53-1S and p53-1223AS. These mutants were cloned into pENTR-D-TOPO, and then transferred to pMXs-gw by Gateway cloning technology.

Effect of p53 suppression in iPS cell generation from MEF

Wild type, p53+/-, or p53-/- MEFs, which also contain the Nanog-GFP reporter, were seeded at 1x 105 cells per well of 6 well plates. Retroviral transduction was performed the next day (day 0) with retrovirus made from Plat-E. On day 5, cells were re-seeded either at one cell per well of 96-well plates by a cell sorter (FACS Aria, Beckton Dekinson) or 5000 cells per 100 mm-dish. Puromycin selection (1.5 μg/ml) was initiated on day 13 in the four-factor protocol and on day 19 in the three factor protocol. Numbers of GFP positive colonies were determined on day 21 for the four-factor protocol and on day 28 in the three factor protocol. In addition to the targeted disruption, p53 was suppressed in MEF by a dominant negative mutant, P275S.

Effect of p53 suppression in iPS cell generation from HDF

Function of p53 was suppressed in HDF either by the dominant negative mutants (P275S or DD) or by shRNAs (pMKO.1-puro; #8452, pMKO.1-puro p53 shRNA-1; #10671, or pMKO.1-puro p53 shRNA-2; #10672 from Addgene). Retrovirus for the dominant negative mutants, shRNAs, and the four reprogramming factors were produced in PLAT-E cells. For iPS cell generation, we plated at 2 × 105 cells per well of 6-well plate one day before transduction. Next day, HDF were transduced overnight with equal amounts of PLAT-E supernatants containing each retrovirus, supplemented with 4 μg/ml polybrene.

In assays with dominant negative mutants, six days after infection, transduced HDF were harvested and replated at 5 × 103 (with the four reprogramming factors ) or 4 × 104 (with the three factors) per 100-mm dish on mitomycin C-treated SNL feeder cells. Next day, the medium was replaced with Primate ES cell medium (ReproCELL) supplemented with 4 ng/ml bFGF. The medium was changed every other day. We counted the number of iPS cell colonies at day 30 post-transduction (with the four factors) or day 40 (with the three factors).

In the experiments with shRNA-madiated knockdown, six days after infection, the transduced cells were re-plated at 5 × 104 cells per 100-mm dish onto mitomycin C-treated SNL feeder. Next day, we started cultivation of the cells with the human ES cell culture condition. Twenty-four days after transduction, we counted the number of iPS colonies, isolated them, and used for functional analyses analyses.

Generation of iPS cells from T cells

Spleen from p53-null, Nanog-GFP male mouse was dissected, minced and suspended in T cell medium consisted of DMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo). T lymphocytes were isolated by using mouse CD90 microbeads (Miltenyi biotec) and plated at 1 × 106 cells per well of RetroNectin (50 μg ml-1, Takara) -coated 24-well plates in T cell medium supplemented with Dynabeads CD3/CD28 T cell Expander (10 μl for 1 × 106 cells, Invitrogen) and 10 units ml-1 of interleukin-2 (IL-2). Retroviruses were prepared as described previously. We added 8 μg ml-1 of polybrene (Nacalai tesque) and 10 units ml-1 of IL-2 to virus-containing supernatant. The four reprogramming factors or DsRed were introduced by retroviral transduction with centrifugation (3000 rpm for 30 minutes), and then incubated in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. Twenty-four hours after transduction, the medium was replaced, then half of the medium was changed every other day. Two-weeks after transduction, the cells were plated at 5 × 104 cells per 100 mm dish onto mitomycin C-treated puromycin resistant SNL feeder in ES medium, which consisted of DMEM (Nacalai tesque) supplemented with 15% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 1 × 10-4 M non essential amino acids (Invitrogen), 1 × 10-4 M 2-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen) and 0.5% penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen). The next day, selection was started with 1.5 μg ml-1 puromycin for 5 days.

V-(D)-J DNA rearrangements of Tcrβ gene were confirmed by PCR with primers Dβ2 (GTAGGCACCTGTGGGGAAGAAACT) and Jβ2 (TGAGAGCTGTCTCCTACTATCGATT). PCR products were separated on a 1.2% agarose gel.

Functional analyses of p53 target genes

Open reading frames of p53 target genes were amplified by PCR and subcloned into pENTR-D-TOPO. Some target genes were obtained from National Institute of Technology and Evaluation (NITE, Japan). These cDNA were transferred to pMXs-gw by using the gateway cloning system. We transduced retroviruses of each of the p53 target genes along with the reprogramming factors, either with or without the p53 knockdown construct. Six days after infection, cells were harvested and re-plated at 5 × 104 cells per 100-mm dish on mitomycin C-treated SNL feeder cells. Next day, we started cultivation of the cells with human ES cell culture condition. We counted the number of iPS cell colonies at day 24 (with four factors) or 28 (with factors) after transduction.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

REFERENCES

- 1.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maherali N, et al. Directly reprogrammed fibroblasts show global epigenetic remodelling and widespread tissue contribution. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(1):55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germ-line competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wernig M, et al. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318(5858):1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowry WE, et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from dermal fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(8):2883–2888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711983105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park IH, et al. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451(7175):141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamanaka S. Strategies and new developments in the generation of patient-specific pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(1):39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakagawa M, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(1):101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wernig M, Meissner A, Cassady JP, Jaenisch R. c-Myc is dispensable for direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(1):10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao Y, et al. Two supporting factors greatly improve the efficiency of human iPSC generation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(5):475–479. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Vries A, et al. Targeted point mutations of p53 lead to dominant-negative inhibition of wild-type p53 function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(5):2948–2953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052713099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shinmura K, Bennett RA, Tarapore P, Fukasawa K. Direct evidence for the role of centrosomally localized p53 in the regulation of centrosome duplication. Oncogene. 2007;26(20):2939–2944. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cecchinelli B, et al. Ser58 of mouse p53 is the homologue of human Ser46 and is phosphorylated by HIPK2 in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13(11):1994–1997. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morita S, Kojima T, Kitamura T. Plat-E: an efficient and stable system for transient packaging of retroviruses. Gene Ther. 2000;7(12):1063–1066. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowman T, et al. Tissue-specific inactivation of p53 tumor suppression in the mouse. Genes Dev. 1996;10(7):826–835. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.7.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart SA, et al. Lentivirus-delivered stable gene silencing by RNAi in primary cells. RNA. 2003;9(4):493–501. doi: 10.1261/rna.2192803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aoi T, et al. Generation of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Mouse Liver and Stomach Cells. Science. 2008;321:699–702. doi: 10.1126/science.1154884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okita K, Nakagawa M, Hyenjong H, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of Mouse Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Without Viral Vectors. Science. 2008;322(5903):949–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1164270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]