Abstract

Objectives

Use of prescription opioids for chronic pain is increasing, as is abuse of these medications, though the nature of the link between these trends is unclear. These increases may be most marked in patients with mental health (MH) and substance use disorders (SUDs). We analyzed trends between 2000 and 2005 in opioid prescribing among individuals with non-cancer pain conditions (NCPC), with and without MH and SUDs.

Methods

Secondary data analysis of longitudinal administrative data from two dissimilar populations: a national, commercially-insured population, and Arkansas Medicaid enrollees. We examined these opioid outcomes: (1) Rates of any prescription opioid use in the past year, (2) rates of chronic use of prescription opioids (greater than 90 days in the past year), (3) mean days supply of opioids, (4) mean daily opioid dose in morphine equivalents, and (5) percentage of total opioid dose that was Schedule II opioids.

Results

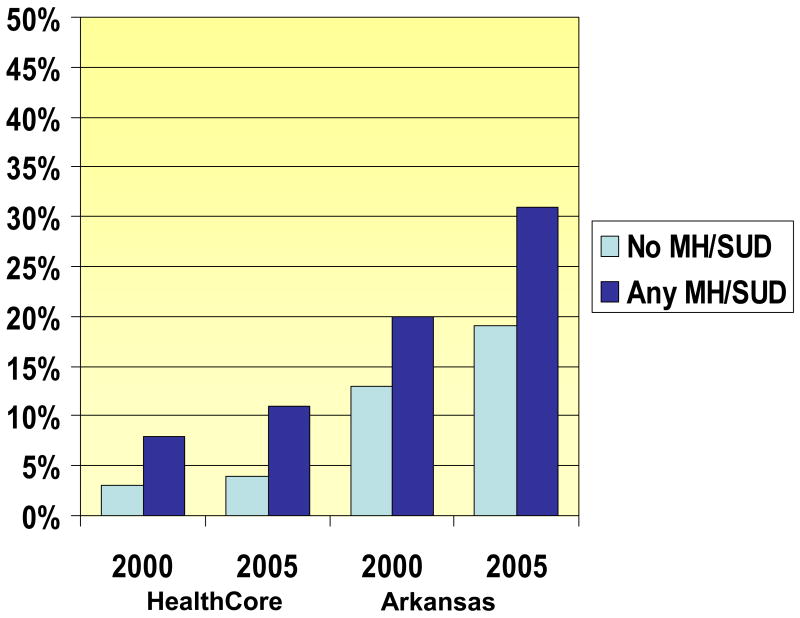

In 2000, among individuals with NCPC, chronic opioid use was more common among those with a MH or SUD than those without in commercially insured (8% versus 3%, p<0.001) and Arkansas Medicaid (20% versus 13%, p<0.001). Between 2000 and 2005, in commercially insured, rates of chronic opioid use increased by 34.9% among individuals with an MH or SUD, and 27.8% among individuals without these disorders. In Arkansas Medicaid chronic opioid use increased 55.4% among individuals with an MH or SUD, and 39.8% among those without.

Discussion

Chronic use of prescription opioids for NCPC is much higher and growing faster in patients with MH and SUDs than those without these diagnoses. Clinicians should monitor use of prescription opioids in these vulnerable groups to determine whether opioids are substituting for or interfering with appropriate mental health and substance abuse treatment.

Introduction

Approximately 20% of the U.S. population is significantly affected by pain lasting at least 6 months,1, 2 most commonly back pain, joint pain and headache.3-7 Individuals with non-cancer pain conditions (NCPC) now commonly receive opioids as treatment for their NCPC.8-10 This increased use is controversial, with some believing that increased use of opioids for NCPC is a sign of better pain treatment,11 while others warn that we do not have enough evidence of the “safety and effectiveness of long-term opioid therapy” in NCPC to justify its use.12 Further, there are concerns about “iatrogenic opioid addiction,”13-21 opioid-induced hyperalgesia,22 and opioid-induced decreases in quality of life.23

It is likely that increased use of opioids both improves pain control and increases risk of misuse and addiction. Reflecting the key issue of balancing the benefits and risks, the Food and Drug Administration recently indicated that manufacturers of certain opioid drug products will be required to have a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy to “ensure that the benefits of the drugs continue to outweigh the risks24

The clinical epidemiology of opioid use for NCPC is not well characterized, particularly in different subgroups. The comorbidity of NCPC with mental health (MH) disorders, such as depression or anxiety, is well established25-27, although little is known about the relationship between NCPC and substance use disorders (SUDs), such as alcohol or drug dependence. There has been debate about whether these NCPC precede or follow these MH disorders, but the best evidence suggests that both pathways are important. Several factors make the subgroup of NCPC patients with MH and SUDs particularly important to study. Because patients with MH and SUDs have often been excluded from randomized opioid trials, we know less about the benefits of NCPC treatment with opioids in this group.28 Further, MH and SUD disorders may be risk factors for abuse of prescribed opioids.6, 9, 14, 18, 19 Thus, individuals with MH and SUDs comprise the population where the benefits of opioids are least established and the vulnerability to opioid addiction is highest. Studies from pain clinics and population surveys suggest that NCPC patients with MH and SUDs are more likely to receive opioids for NCPC 29,18, 30-32 than NCPC patients without MH or SUDs, but the number of opioid users in these studies has been small and details of opioid use are lacking.

Our objective was to analyze trends in opioid prescribing among individuals with NCPC, with and without MH and SUDs, focusing on years 2000 and 2005. We utilized longitudinal administrative data from two dissimilar populations: a national, commercially-insured population, and Arkansas Medicaid, to demonstrate the range of current trends. The use of administrative data has several advantages for this type of analysis, when compared to studies from pain clinics or community surveys. First, administrative data offers much larger samples, allowing extensive subgroup analysis. Second, samples from entire health plans are more representative than samples from primary or specialty clinical settings. Third, administrative pharmacy records offer detailed information on type of opioid, dose, and days supplied. Fourth, they do not suffer from recall bias, as might occur with surveys.

We focused on years 2000 and 2005, as we have previously shown that rates of increase were linear between those years,33, 34 and investigated (i) rates of any prescription opioid use among individuals with NCPC and either mental health or substance use disorders, (ii) rates of use of prescription opioids for greater than 90 days in the past year, (iii) mean days supply of prescription opioids, among those prescribed any opioids, (iv) mean daily opioid dose in morphine equivalents, and (5) the percentage of the total opioid dose that was Schedule II opioids. These years are of particular interest because in 2000 the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations initiated its “Pain as the fifth vital sign” campaign to promote appropriate pain treatment.35

Materials and Methods

Study Populations

Arkansas Medicaid

Arkansas is one of the poorest states, with 26% of the Arkansas population qualifying for Medicaid benefits in 2005.36 The 2005 total expenditures for the program were $3.0 billion dollars or $4,368 per recipient. Arkansas Medicaid serves a disadvantaged and vulnerable population situated in the geographic region with the highest opioid use in the country.30 Arkansas Medicaid covers all federally-mandated services and nearly all federal optional services, including prescription drug, ambulatory surgical center services, and 44 other optional services. Most Arkansas Medicaid enrollees participate in the primary care physician program where recipients utilize a primary care provider to coordinate care. The Arkansas Medicaid program imposes some benefit limitations: 12 physician, clinic, and/or outpatient visits per year, 6 prescriptions per month, maximum of 24 inpatient days per year, and some co-insurance and co-payments for prescription drugs and other services depending on eligibility type. Analyses of Medicaid claims indicate that Medicaid data are generally valid and suitable for epidemiologic uses.37

HealthCore

The HealthCore Integrated Research Database contains medical and pharmacy administrative claims and health plan eligibility data from 5 commercial health plans representing the West, Mid-West, and South-East regions. Data came from health plan members who were fully-insured via several commercial insurance products including health maintenance organizations, preferred provider organizations, and point of service providers. Health plan members all had full medical and pharmacy coverage, with a range of co-pay and deductibles. Claims submitted with partial or complete subscriber liability (due to co-pay or deductible requirements) are captured.

Study Sample

The study sample consisted of enrollees in the two health plans in 2000 and 2005 who met the following criteria. Inclusion Criteria: 1) One or more recorded NCPC diagnosis based on ICD codes for back pain, neck pain, arthritis/joint pain, headache/migraine, and HIV/AIDS. We could not verify that these conditions were chronic or that these were the conditions for which opioids were prescribed, but chronic forms of these conditions are the most common indication for long-term opioid use in a general medical population. 2) Age 18 or older. 3) Enrolled and eligible for benefits for at least 9 months in 2000 or 2005. Exclusion Criteria: 1) Cancer diagnosis at any time in 2000-5 other than non-melanoma skin cancer, 2) resident of nursing home, or 3) receiving hospice benefits. These criteria allow us to focus on out-patient enrollees likely receiving opioids for the treatment of NCPC.

Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders

Using ICD-9-CM codes we created a dichotomous variable for 6 types of disorders using validated grouping software developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality:38 adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, substance use disorders, and miscellaneous disorders (e.g., eating disorders, somatoform disorders). We also summed the number of types of disorders, from 0 to 6. We also created a category of MH disorder (any adjustment, anxiety, mood, personality, or miscellaneous MH disorder) comorbid with an SUD.

Opioid Use

Data included all opioid prescriptions (including date, dose, and type of opioid) regardless of indication for opioid use. Buprenorphine was excluded, as the oral formulation is not FDA approved for pain treatment.

For years 2000 and 2005 we formed an analytic file including all individuals with one of our tracer NCPC diagnoses in one of those years. We recorded the total number of opioid prescription fills for each patient within the calendar year and calculated the number of days supplied in the year, as recorded by the dispensing pharmacist.

There is no standard definition of chronic opioid therapy, so we relied on our clinical judgment, and the frequency distribution of number of days of opioids used, to define chronic opioid therapy as receiving greater than 90 days supply of opioids during the calendar year. This threshold was chosen because it is unlikely that an individual would receive opioids for greater than 90 days (4 prescriptions) for acute conditions. Further, it appears that 90 days represents an important point in the treatment process where clinicians will want to know the clinical risk of continuing opioid therapy. Finally, in our data, of those individuals with more than 90 days of opioid use in one calendar year, approximately 25% go on to >180 days in the following year. Hence, we believe this is a reasonable ‘gateway’ or ‘threshold’ time point for trend and risk analyses.

Opioids were categorized into Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Schedule II opioids, and Schedule III-IV opioids.39 Schedule II opioids are the most highly regulated, and are felt to be most prone to abuse, but abuse of Schedule III hydrocodone products is the most common form of prescription opioid abuse. Total morphine equivalents for each prescription were calculated by multiplying the quantity of each prescription by the strength of the prescription (milligrams of opioid per unit dispensed). The quantity-strength product was then multiplied by conversion factors derived from published sources to estimate the milligrams of morphine equivalent to the opioids dispensed in the prescription.40-42 The total average dose in morphine equivalents per day supplied was calculated by summing the morphine equivalents for each prescription filled during the year for each patient, and dividing by the number of days supplied. The percentage of the morphine equivalents that were Schedule II opioids was calculated by dividing the Schedule II morphine equivalents dose by the total morphine equivalents dose.

Data Quality Issues

To protect against data entry errors, we treated as an outlier any value for days supply or quantity greater than two times the 99th percentile value for the particular opioid. Outliers were then handled as if they were missing data. If either quantity or days supply was missing for a particular prescription, then morphine equivalents were not calculated for that prescription. The estimate of total morphine equivalents was inflated by the total number of prescriptions in the year (including those with missing data) divided by the number of prescriptions with valid data (i.e. not counting the ones with missing/outlier data). This approach conservatively estimates the morphine equivalents for prescriptions with missing/outlier data as being equal to the average prescription in the year. In both samples, total missing was less than 1.5% and outliers were less than 0.5%

Analysis

We first calculated the percentage of enrollees with a NCPC diagnosis in 2000 and 2005 for each plan. Among enrollees with a NCPC diagnosis, we calculated the percentage with 1, 2, 3, or 4+ unique MH and SUD diagnosis types as per AHRQ categories (adjustment disorder, anxiety disorder, mood disorder, personality disorder, substance use disorder, and miscellaneous), and the percentage with each particular MH or SUD tracer diagnosis. We calculated the percentage of individuals with NCPC who had any prescription opioid use, and the percentage who had greater than 90 days supply in the calendar year, by number and type of MH or SUDs. We compared the percentage having greater than 90 days supply between patients with and without any MH or SUD disorders using Chi-square tests. For those with any opioid use, we calculated the average number of days supplied and average dose per day in morphine equivalents.

We computed the percent change between 2000 and 2005 data for each variable. The 95% confidence intervals for percent change were derived using Fieller's method. All the analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

In the 2000 HealthCore sample, the average age was 45, and 57% were female; in the Arkansas Medicaid sample in 2000 the average age was 55, and 76% were female, reflecting the fact that most adults Medicaid recipients are female. The overall burden of pain conditions was higher in the Medicaid plan; in 2005, 23.8% of the HealthCore enrollees had at least one NCPC diagnosis, while 34.0% of the Arkansas Medicaid enrollees had at least one NCPC diagnosis.

Among enrollees with a NCPC diagnosis, the percentage with a MH and SUD diagnosis increased substantially between 2000 and 2005 (Table 1). Among HealthCore enrollees with NCPC diagnoses, the percentage with a MH or SUD diagnosis increased from 10.1% in 2000 to 14.9% in 2005, and in Arkansas Medicaid the percentage increased from 23.7% to 35.1%. The rates of increase in MH and SUDs were especially large for enrollees with anxiety, mood, and substance use diagnoses, comorbid MH/SUDs, and for enrollees with multiple MH and SUD diagnoses.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders Among Individuals with Non-Cancer Pain Conditions.

| Health Core | Arkansas Medicaid | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MH/SUD Diagnosis | 2000 (N=485,794) N (%) |

2005 (N=897,537) N (%) |

% change 00∼05 [95% CI] |

2000 (N=36,283) N (%) |

2005 (N=43,520) N (%) |

% change 00∼05 [95% CI] |

| Disorder Type | ||||||

| Adjustment Disorder | 8,948 (1.8) | 17,366 (1.9) | 5.0 [2.5, 7.7] | 687 (1.9) | 926 (2.1) | 12.4 [2.1, 23.8] |

| Anxiety Disorder | 17,018 (3.5) | 56,006 (6.2) | 78.1 [75.2, 81.1] | 3,622 (10.0) | 7,769 (17.9) | 78.8 [72.7, 85.3] |

| Mood Disorder | 26,027 (5.4) | 76,908 (8.6) | 59.9 [57.8, 62.1] | 5,456 (15.0) | 10,650 (24.5) | 62.7 [58.4, 67.3] |

| Personality Disorder | 542 (0.1) | 1,283 (0.1) | 28.1 [16.2, 41.9] | 606 (1.7) | 1,107 (2.5) | 52.3 [39.1, 67.2] |

| Substance Disorder | 3,629 (0.7) | 10,449 (1.2) | 55.8 [50.2, 61.8] | 1,361 (3.8) | 2,950 (6.8) | 80.7 [70.3, 92.0] |

| Miscellaneous Disorder | 3,974 (0.8) | 12,076 (1.3) | 64.5 [58.8, 70.5] | 607 (1.7) | 1,180 (2.7) | 62.1 [47.6, 78.5] |

| Comorbid MH/SUD | 1,737 (0.4) | 5,807 (0.6) | 80.9 (71.7, 91.0) | 868 (2.4) | 2,155 (5.0) | 107.0 (92.4, 123.3) |

| No Disorder | 436,859 (89.9) | 763,967 (85.1) | -5.3 [-5.5, -5.2] | 27,669 (76.3) | 28,255 (64.9) | -14.9 [-15.6, -14.1] |

| Number of MH/SUD Disorder types | ||||||

| Any Disorder | 48,935 (10.1) | 133,570 (14.9) | 47.7 [46.3, 49.2] | 8,614 (23.7) | 15,265 (35.1) | 47.4 [44.7, 50.9] |

| 1 Disorder | 39,533 (8.1) | 100,062 (11.1) | 37.0 [35.5, 38.5] | 5,730 (15.8) | 8,663 (19.9) | 26.0 [22.4, 29.8] |

| 2 Disorders | 7,855 (1.6) | 27,449 (3.1) | 89.1 [84.6, 93.9] | 2,176 (6.0) | 4,476 (10.3) | 71.5 [63.6, 80.0] |

| 3 Disorders | 1,322 (0.3) | 5,206 (0.6) | 113.1 [100.9, 126.6] | 590 (1.6) | 1,634 (3.8) | 130.9 [111.2, 153.4] |

| 4+ Disorders | 225 (0.1) | 853 (0.1) | 105.2 [78.2, 139.3] | 118 (0.3) | 492 (1.1) | 247.6 [188.4, 329.7] |

Table 2 describes rates of any use of prescribed opioids, and >90 days use of prescribed opioids in a calendar year, among those with NCPC, by MH and SUD categories. In both Arkansas Medicaid and HealthCore, those with a MH or SUD diagnosis were more likely to have any opioid use. Among those with any MH or SUD, those with more diagnoses had higher rates of any opioid use (p<0.0001, for both samples, in both 2000 and 2005). Rates of any opioid use were substantially higher in Arkansas Medicaid than in HealthCore, but rates of any opioid use increased between 2000 and 2005 for almost all groups. Rates of opioid use were especially high in the comorbid MH/SUD category.

Table 2.

Any Opioid Use and Chronic Opioid Use, among Non-Cancer Pain Patients, Stratified by Number and Type of MH/SUD Diagnoses.

| Health Core | Arkansas Medicaid | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MH/SUD Diagnosis | Any Opioid Use | 2000 (N=485,794) N (%) |

2005 (N=897,537) N (%) |

% change 00∼05 [95% CI] |

2000 (N=36,283) N (%) |

2005 (N=43,520) N (%) |

% change 00∼05 [95% CI] |

| Disorder Type | |||||||

| Adjustment Disorder | Any Use | 3,012 (34) | 6,996 (40) | 19.7 [15.7, 23.9] | 422 (61) | 648 (70) | 13.9 [5.9, 22.8] |

| >90 days | 428 (5) | 1,219 (7) | 46.8 [32.3, 63.8] | 110 (16) | 237 (26) | 59.8 [31.3, 98.1] | |

| Anxiety Disorder | Any Use | 6,719 (39) | 26,316 (47) | 19.0 [16.6, 21.5] | 2,430 (67) | 6,008 (77) | 15.3 [12.4, 18.2] |

| >90 days | 1,359 (8) | 6,255 (11) | 39.9 [32.4, 48.0] | 843 (23) | 2,808 (36) | 55.3 [45.9, 65.7] | |

| Mood Disorder | Any Use | 10,779 (41) | 37,468 (49) | 17.6 [15.8, 19.5] | 3,382 (62) | 7,706 (72) | 16.7 [14.1, 19.5] |

| >90 days | 2,406 (9) | 9,422 (12) | 32.5 [27.2, 38.2] | 1,021 (19) | 3,235 (30) | 62.3 [53.1, 72.5] | |

| Personality Disorder | Any Use | 244 (45) | 640 (50) | 10.8 [-0.3, 23.9] | 342 (56) | 773 (70) | 23.7 [14.6, 34.1] |

| >90 days | 59 (11) | 165 (13) | 18.1 [-9.3, 60.1] | 91 (15) | 285 (26) | 71.4 [40.3, 115.2] | |

| Substance Disorder | Any Use | 2,068 (57) | 6,511 (62) | 9.3 [6.0, 12.9] | 931 (68) | 2,242 (76) | 11.1 [6.7, 15.8] |

| >90 days | 735 (20) | 2,336 (22) | 10.4 [2.7, 18.9] | 349 (26) | 1,042 (35) | 37.7 [25.0, 52.7] | |

| Miscellaneous | Any Use | 1,610 (41) | 5,531 (46) | 13.1 [8.4, 18.0] | 368 (61) | 867 (73) | 21.2 [12.8, 30.6] |

| >90 days | 384 (10) | 1371 (11) | 17.5 [5.9, 31.2] | 111 (18) | 360 (31) | 66.8 [39.4, 104.0] | |

| Comorbid MH/SUD | Any Use | 1085 (62) | 3821 (66) | 5.3 [1.2, 9.8] | 613 (71) | 1678 (78) | 10.3 [5.2, 15.7] |

| > 90 days | 449 (26) | 1555 (27) | 3.6 [-5.1, 13.6] | 232 (27) | 816 (38) | 41.7 [26.2, 60.5] | |

| Number of MH Disorder Types | |||||||

| No Disorder | Any Use | 127,497 (29) | 260,255 (34) | 16.7 [16.1, 17.4] | 13,996 (51) | 16,519 (58) | 15.6 [13.9, 17.2] |

| >90 days | 12,909 (3) | 28,853 (4) | 27.8 [25.3, 30.3] | 3664 (13) | 5,230 (19) | 39.8 [35.0, 44.8] | |

| Any Disorder | Any Use | 19,133 (39) | 61,868 (46) | 18.5 [17.0, 19.9] | 5,374 (62) | 11,096 (73) | 16.5 [14.4, 18.7] |

| >90 days | 3,874 (8) | 14,261 (11) | 34.9 [30.5, 39.5] | 1725 (20) | 4,750 (31) | 55.4 [48.6, 62.7] | |

| 1 Disorder | Any Use | 14,858 (38) | 44,456 (44) | 18.2 [16.5, 19.9] | 3,455 (60) | 6,064 (70) | 16.1 [13.3, 19.0] |

| >90 days | 2,733 (7) | 9,279 (9) | 34.1 [28.9, 39.8] | 1108 (19) | 2,489 (29) | 48.6 [40.0, 58.0] | |

| 2 Disorders | Any Use | 3,426 (44) | 13,853 (50) | 15.7 [12.6, 19.0] | 1438 (66) | 3,384 (76) | 14.4 [10.6, 18.4] |

| >90 days | 850 (11) | 3,703 (13) | 24.7 [16.4, 33.9] | 465 (21) | 1,521 (34) | 59.0 [45.8, 74.3] | |

| 3 Disorders | Any Use | 697 (53) | 3,002 (58) | 9.4 [3.5, 15.8] | 392 (66) | 1,255 (77) | 15.6 [8.6, 23.3] |

| >90 days | 233 (18) | 1,060 (20) | 15.5 [2.2, 32.1] | 125 (21) | 555 (34) | 60.3 [36.6, 91.9] | |

| 4+ Disorders | Any Use | 152 (68) | 557 (65) | -3.3 [No closed CI] | 89 (75) | 393 (80) | 5.9 [-4.8, 18.8] |

| >90 days | 58 (26) | 219 (26) | -0.4 [No closed CI] | 27 (23) | 185 (38) | 64.3 [20.9, 147.7] | |

Among individuals with NCPC, the proportion of individuals with chronic opioid use (greater than 90 days supply) was higher than among those with an MH or SUD diagnosis than those without a MH or SUD diagnosis (Table 2). For example, in the 2005 HealthCore data, individuals with a mood disorder diagnosis were three times more likely to have greater than 90 days of opioid use, compared to those with no mood disorder diagnosis (12% vs. 4%, p<0.001). Chronic opioid use was found in nearly one-third (31%) of Arkansas Medicaid enrollees with a MH or SUD diagnosis, in 2005. The rates of chronic opioid use (greater than 90 days) also grew substantially between 2000 and 2005 for enrollees in both health plans with NCPC and any MH or SUD diagnosis (34.9% increase among HealthCore, and an increase of 55.4% among Arkansas Medicaid enrollees).

Table 3 provides data on days supply, and percentage of the total opioid dose that was Schedule II opioids, among enrollees with NCPC and any opioid use. In both Arkansas Medicaid and HealthCore individuals with an MH or SUD diagnoses received greater days supply of opioids than individuals without a MH or SUD, and these differences were large and consistent across years. For example, in the 2005 HealthCore population, among those who received any opioids, individuals without a MH or SUD diagnosis received on average 44.0 days of opioids, while those with any MH or SUD diagnosis received 89.6 days (p<0.001). In 2005, among HealthCore enrollees with a MH or SUD diagnosis, the average days supply ranged from individuals from 81 days for those with one diagnosis to 161 days for those with a comorbid MH/SUD. In the 2005 Arkansas Medicaid population, among those who received any opioids, individuals without a MH or SUD diagnosis received on average 102.6 days of opioids, while those with any MH or SUD diagnosis received 136.3 days (p<0.001). The days supplied increased significantly between 2000 and 2005 for all diagnostic groups, but rates of increase were higher among those with any MH or SUD diagnosis in both populations.

Table 3.

Among Opioid Users with Non-Cancer Pain Conditions, Mean Days Supply in Past 12 months, and percent of total opioid dose that was Schedule II

| Health Core | Arkansas Medicaid | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MH/SUD Diagnosis | Opioid Use | 2000 (N=146,630) Mean (SD) |

2005 (N=322,123) Mean (SD) |

% change 00∼05 [95% CI] |

2000 (N=19,370) Mean (SD) |

2005 (N=27,615) Mean (SD) |

% change 00∼05 [95% CI] |

| Disorder Type | |||||||

| Adjustment Disorder | Days supply | 51.7 (113.8) | 67.7 (144.9) | 31.0 [19.6, 44.0] | 88.1 (138.7) | 111.6 (142.5) | 26.7 [6.7, 52.6] |

| Schedule II | 10.4 (27.6) | 15.7 (32.5) | 51.9 [37.0, 69.7] | 13.4 (29.4) | 15.7 (31.8) | 16.9 [-9.3, 53.7] | |

| Anxiety Disorder | Days supply | 70.4 (135.0) | 89.2 (164.2) | 26.8 [20.6, 33.5] | 106.6 (144.5) | 145.5 (161.9) | 36.5 [28.9, 44.9] |

| Schedule II | 12.3 (29.1) | 16.6 (32.8) | 35.6 [27.7, 44.4] | 11.7 (27.8) | 16.2 (32.3) | 39.1 [25.7, 54.9] | |

| Mood disorder | Days supply | 79.2 (144.0) | 97.6 (178.1) | 23.3 [18.7, 28.1] | 94.4 (140.7) | 132.4 (160.4) | 40.2 [32.9, 48.1] |

| Schedule II | 13.4 (30.4) | 18.0 (34.0) | 34.4 [28.4, 41.0] | 12.6 (29.1) | 17.0 (33.0) | 34.7 [23.8, 47.2] | |

| Personality disorder | Days supply | 92.3 (162.8) | 96.0 (168.2) | 4.0 [-18.8, 37.4] | 86.4 (128.4) | 113.8 (146.8) | 31.7 [11.4, 58.3 |

| Schedule II | 12.6 (29.5) | 20.7 (35.2) | 64.3 [22.3, 137.3] | 11.9 (27.9) | 16.4 (33.1) | 38.1 [6.1, 87.8] | |

| Substance disorder | Days supply | 125.6 (190.1) | 146.2 (221.0) | 16.4 [8.2, 25.6] | 116.3 (156.5) | 151.8 (176.1) | 30.5 [18.8, 44.2] |

| Schedule II | 20.3 (35.5) | 26.3 (38.7) | 29.7 [19.5, 41.3] | 17.0 (33.5) | 23.5 (37.3) | 38.2 [20.7, 60.2] | |

| Miscellaneous | Days supply | 89.7 (157.7) | 103.8 (195.0) | 15.7 [5.0, 28.1] | 91.4 (128.5) | 143.7 (182.2) | 57.2 [34.1, 86.9] |

| Schedule II | 16.8 (33.7) | 20.9 (36.4) | 24.5 [12.1, 39.4] | 13.6 (30.4) | 23.4 (37.3) | 72.6 [36.5, 127.6] | |

| Comorbid MH/SUD | Days supply | 147.9 (202.5) | 161.4 (226.3) | 9.2 [-0.3, 20.1] | 117.0 (154.7) | 156.3 (175.3) | 33.6 [19.5, 50.6] |

| Schedule II | 21.4 (35.8) | 27.4 (38.9) | 28.0 [15.1, 43.4] | 16.6 (32.7) | 23.8 (37.4) | 43.7 [22.1, 72.5] | |

| Number of MH/SUD Disorder types | |||||||

| No Disorder | Days supply | 38.3 (92.6) | 44.0 (109.2) | 14. 9 [13.2, 16.6] | 81.5 (122.9) | 102.6 (145.3) | 25.9 [22.3, 29.7] |

| Schedule II | 9.2 (26.5) | 13.1 (30.5) | 41.7 [39.2, 44.2] | 8.8 (25.4) | 11.3 (28.5) | 28.7 [21.6, 36.3] | |

| Any MH/SUD Disorder | Days supply | 72.1 (138.1) | 89.6 (170.1) | 24.3 [20.6, 28.1] | 100.1 (143.3) | 136.3 (163.1) | 36.1 [30.6, 42.0] |

| Schedule II | 12.9 (30.1) | 17.4 (33.7) | 34.7 [30.0, 39.7] | 12.5 (29.0) | 16.7 (32.9) | 33.9 [25.0, 43.7] | |

| 1 Disorder | Days supply | 65.5 (129.4) | 81.3 (161.4) | 24.2 [19.8, 28.8] | 99.9 (143.5) | 131.6 (161.3) | 31.7 [24.7, 39.3] |

| Schedule II | 12.4 (29.6) | 16.6 (33.1) | 34.3 [28.8, 40.3] | 12.0 (28.8) | 14.9 (31.5) | 23.7 [12.8, 36.1] | |

| 2 Disorders | Days supply | 90.1 (161.2) | 103.1 (180.9) | 14.4 [7.2, 22.4] | 101.2 (143.3) | 143.0 (167.3) | 41.4 [30.6, 53.6] |

| Schedule II | 14.5 (31.2) | 18.3 (34.1) | 26.3 [17.1, 36.9] | 12.4 (28.6) | 18.1 (33.7) | 45.9 [28.4, 67.5] | |

| 3 Disorders | Days supply | 109.0 (162.4) | 138.3 (214.4) | 26.8 [12.6, 44.2] | 100.3 (144.6) | 140.0 (162.2) | 39.5 [20.4, 64.3] |

| Schedule II | 15.0 (31.2) | 23.3 (37.0) | 55.3 [33.0, 85.3] | 15.8 (31.7) | 20.2 (35.2) | 27.9 [4.0, 62.1] | |

| 4 Disorders | Days supply | 143.9 (194.4) | 152.7 (210.1) | 6.1 [-15.7, 38.1] | 88.7 (130.5) | 137.6 (153.7) | 55.1 [16.3, 125.4] |

| Schedule II | 24.3 (37.9) | 28.6 (39.1) | 17.8 [-8.5, 59.7] | 15.9 (31.2) | 21.4 (36.3) | 34.9 [-8.5, 131.9] | |

Table 3 also shows the percentage of the total opioid dose that was Schedule II. While the large majority of opioid use was non-Schedule II, the percentage of Schedule II opioid use was higher in individuals with MH/SUD diagnoses than those without an MH/SUD diagnosis. For example, among Health Core patients with an MH/SUD in 2005, 17.4% of their total opioid use (both Schedule II and III) was schedule II; the corresponding figure in 2005 for Health Core patients with no MH/SUD was 13.1%. The percentage of Schedule II opioids increased rapidly in all groups between 2000 and 2005. The average daily dose of opioids in milligram morphine equivalents was generally between 50 and 55 milligrams, and dose did not vary widely between diagnostic subgroups or health plans (data not shown). The average daily dose generally increased (<10%) between 2000 and 2005 in HealthCore, and decreased (<10%) in Arkansas Medicaid.

Figure.

Rates of Chronic Opioid Use (>90 days per year)

Discussion

Our study of two dissimilar clinical populations revealed that chronic opioid use for patients with NCPC was more common, and increased more rapidly from 2000 to 2005 among enrollees with MH/SUD diagnoses in both populations. Duration and potency of opioid therapy (% of Schedule II opioids) were significantly higher in patients with an MH/SUD diagnosis. Since patients with MH/SUD diagnoses have been excluded from most trials of opioid therapy for NCPC, there is no evidence base for these prescribing trends. Treatment guidelines recommend caution in prescribing opioids to patients with SUDs, but are generally silent about MH disorders as risk factors for opioid abuse, although they do mention the necessity of assessment and appropriate treatment of MH disorders in this population.

Increasing Rates of MH/SUD Diagnoses in NCPC Patients

Rates of MH/SUD diagnosis among patients with NCPC increased by nearly 50% in both populations during this period. Mood, anxiety and substance abuse disorders were the most common MH/SUD diagnoses and increased the most from 2000 to 2005. By 2005 over a third of the adult Arkansas Medicaid NCPC patients had a MH/SUD diagnosis. These increased rates of diagnosis may be due to better detection of MH disorders or SUDs in primary care. While the population prevalence of mental disorders did not increase between 1990 and 2003, the rates of treatment increased significantly.43 These increasing rates of treatments were most marked in the general medical sector where most chronic pain treatment takes place.44 These increases in rates of treatment are likely accompanied by increases in rates of diagnosis. Also, it is believed that direct-to-consumer advertising both increased recognition of the MH symptoms and diminished stigma associated MH disease, resulting in higher diagnosis and treatment rates, although this does not explain the increased rate of SUD diagnoses.

However, non-detection and under-diagnosis of MH/SUDs occurs commonly, and the true rates of MH/SUDs in the population of patients with NCPC may be higher. Rates of MH and SUD diagnoses in the Health Core population tended to be lower than estimates from population surveys,45, 46 while in the Arkansas Medicaid sample rates of MH diagnoses were higher than estimates from population surveys, but rates of SUDs tended to be similar.

Opioid Use Higher in Individuals with MH/SUDs

Among individuals with NCPC, those with MH/SUD diagnoses were more likely to receive opioids than those without MH/SUD diagnoses. The differences between NCPC patients with and without MH/SUD diagnosis were even larger when we investigated chronic use (greater than 90 days of opioids). In Healthcore, individuals with NCPC and a MH/SUD diagnosis were nearly three times more likely to have more than 90 days of opioid use, compared to enrollees with just NCPC (11% vs. 4%). In Arkansas Medicaid in 2005, fully 31% of eligible individuals with NCPC and a MH/SUD diagnosis received more than 90 days of opioids. Further, the percentage of the total opioid dose that was schedule II opioids was higher among individuals with MH/SUD disorders than those without these disorders.

We cannot definitively state why NCPC enrollees with MH/SUDs were more likely to receive opioids than NCPC enrollees without MH/SUDs, and to receive them chronically, but there are a number of potential reasons. First, individuals who have greater use of opioids may have more severe pain with more activity interference, precipitating both their MH diagnosis and opioid use.47 Second, MH and SUDs may increase pain caused by CNCPs48 and decrease responsiveness to opioids,49 requiring greater use of opioids. Third, individuals with MH/SUDs may be using the opioids to “self-medicate” their emotional pain and its associated physical symptoms.50-52 Fourth, individuals with MH/SUDs may be more likely to seek opioids for misuse than individuals without MH/SUDs.1 Fifth, most opioids are prescribed in primary care to patients with multiple physical health and mental health conditions.30 In these complex patients, busy clinicians may focus on the physical symptoms, utilizing opioids to provide relief to their patients. Finally, physicians may be more likely to diagnose MH and SUDs in their patients receiving opioids.

The high (and growing) rates of opioid use among individuals with MH/SUDs may have positive or negative implications for their psychiatric treatment. On the one hand, increased use of opioids may mean improved pain control, which would likely facilitate the treatment of associated mood or anxiety disorders. On the other hand, patients with MH/SUDs have often been excluded from randomized opioid trials, so we know less about the balance of benefits and risks of NCPC treatment with opioids in this group.28 MH/SUD disorders may be risk factors for iatrogenic opioid abuse.6, 9, 14, 18, 19 Thus, the use of opioids is higher, and is growing faster, in the population where the benefits of opioids are least established and the vulnerability to iatrogenic addiction is highest. Further, opioids have a low therapeutic index, and individuals with MH/SUD disorders could intentionally or unintentionally overdose on these medications. There is evidence of increasing intentional and unintentional deaths from opioid overdoses. It is unclear what role MH/SUDs are playing in these.53 Finally, prescription opioids might be substituting for or disrupting other appropriate treatment.54

Future Directions

Patients with chronic pain and mental health or substance use disorders are more distressed and more complicated to care for than patients who have only chronic pain, and there is much we need to understand to improve their clinical care. For example, we need to better understand the relationship between chronic pain and mental health illness, and future studies are needed to disentangle this complex relationship. Further, the optimal treatment for these individuals has not been defined and future studies should focus on ways of improving care for these patients. For example, in one small study investigating the efficacy of a care management model for comorbid depression and osteoarthritis pain in older primary care adults, patients showed improvements in both their depression and pain. 55 In a collaborative care pain intervention in Veterans Affairs primary care clinics, intervention patients experienced greater improvement in pain and depression severity, compared to patients receiving treatment as usual. 56

Limitations

Our data are from diverse sources, but are not nationally representative, so the generalizability to the larger population is unknown. Arkansas Medicaid serves a low income, vulnerable population in the South-Central U.S. HealthCore has enrollees in many states in the Midwest, West, and Southeast, most of whom are working, middle, or upper class. Our intent in investigating these two dissimilar populations was not to draw contrasts, but to describe the current range of opioid prescribing practices. Indeed, the much higher burden of disease in Arkansas Medicaid, measured in terms of both rates of NCPC and MH/SUD diagnoses, makes comparisons problematic. Despite differences in the overall burden of disease and socioeconomic status between the two populations, broad based increases in NCPC diagnosis, chronic opioid use, days supply and opioid potency emerged for patients with MH/SUDs in both groups.

Although we relied upon conversion factors from published sources to derive morphine equivalents, 38-40 there are no canonical conversion tables, and estimates of conversion factors differ, generally by small amounts. Differences between conversion tables were resolved by consensus among the clinicians on this study, in collaboration with other researchers and clinicians.

Methadone presents two challenges for a study such as ours. First, published estimates of conversion factors for methadone to morphine equivalents differ considerably (more so than conversion factors for other opioids to morphine equivalents). Second, we were not able to separate methadone used for pain from methadone used for methadone maintenance. However, methadone accounted for a relatively small amount of total opioid use in our sample, and methadone maintenance is not common. For example, there is only one methadone clinic in all of Arkansas.

We relied upon administrative data for diagnoses and for pharmacy records. No independent clinical assessment of patients to confirm diagnoses could be done. Pain diagnoses have high specificity, although sensitivity is likely lower.57 Our study does not reflect opioids bought over the internet without a prescription,58 or bought illegally. As we analyzed each year's data separately and did not track individual subjects' status from year to year our results represent population trends and not the trends of individual enrollees.

Some mental health and substance use diagnoses may be more “popular” in different time periods. For example, the number of outpatient physician visits for bipolar disorder increased rapidly for children between 1994 and 2003, and also increased for adults.59 The possible implications of this for the current study are uncertain, although we would note that the diagnosis rates increased for all MH/SUDs categories in our study.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that opioid use for NCPC was more common, more prolonged, more potent, and increased more rapidly from 2000 to 2005 among enrollees with MH and SUD diagnoses in both of these populations. As there is no evidence base for these higher rates of opioid use among individuals with MH and SUDs, clinicians should carefully monitor use of prescription opioids in their patients with MH and SUDs and determine whether these are substituting for or interfering with other appropriate mental health and substance abuse treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant DA022560-01.

References

- 1.Strine TW, Hootman JM, Chapman DP, Okoro CA, Balluz L. Health-related quality of life, health risk behaviors, and disability among adults with pain-related activity difficulty. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(11):2042–2048. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verhaak PF, Kerssens JJ, Dekker J, Sorbi MJ, Bensing JM. Prevalence of chronic benign pain disorder among adults: A review of the literature. Pain. 1998;77:231–239. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent pain and well-being: A World Health Organization Study in Primary Care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280(2):147–151. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zerzan JT, Morden NE, Soumerai S, et al. Trends and geographic variation of opiate medication use in state Medicaid fee-for-service programs, 1996 to 2002. Medical Care. 2006;44(11):1005–1010. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228025.04535.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eriksen J, Jensen MK, Sjogren P, Ekholm O, Rasmussen NK. Epidemiology of chronic non-malignant pain in Denmark. Pain. 2003;106(3):221–228. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Hudson T, Harris KM, Sullivan M. Risk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and dependence among veterans using opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2007;129(3):355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Jorm LR, Williamson M, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain in Australia: A prevalence study. Pain. 2001;89:127–134. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caudill-Slosberg MA, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Office visits and analgesic prescriptions for musculoskeletal pain in US: 1980 vs. 2000. Pain. 2004;109(3):514–519. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veterans Health Administration, Department of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain (Version 1.0) Washington D.C.: Veterans Health Administration/Department of Defense; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilson AM, Ryan KM, Joranson DE, Dahl JL. A reassessment of trends in the medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics and implications for diversion control: 1997-2002. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2004;28(2):176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Portenoy RK. Appropriate use of opioids for persistent non-cancer pain. Lancet. 2004;364(9436):739–740. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16951-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Von Korff M, Deyo RA. Potent Opioids for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Flying blind? Pain. 2004;109(3):207–209. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration: Office of Applied Studies. Summary of Findings from the 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schieffer BM, Pham Q, Labus J, et al. Pain medication beliefs and medication misuse in chronic pain. Journal of Pain. 2005;6:620–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zacny J, Bigelow G, Compton P, Foley K, Iguchi M, Sannerud C. College on Problems of Drug Dependence taskforce on prescription opioid non-medical use and abuse: Position statement. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:215–232. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chabal C, Erjavec MK, Jacobson L, Mariano A, Chaney E. Prescription opiate abuse in chronic pain patients: Clinical criteria, incidence, and predictors. Clinical Journal of Pain. 1997;13:150–155. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199706000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jonasson U, Jonasson B, Wickstrom L, Andersson E, Saldeen T. Analgesic use disorders among orthopedic and chronic pain patients at a rehabilitation clinic. Substance Use and Misuse. 1998;33:1375–1385. doi: 10.3109/10826089809062222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reid MC, Engles-Horton LL, Weber MB, Kerns RD, Rogers EL, O'Connor PG. Use of opioid medications for chronic noncancer pain syndromes in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17:173–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cowan DT, Wilson-Barnett J, Griffiths P, Allan LG. A survey of chronic noncancer pain patients prescribed opioid analgesics. Pain Medicine. 2003;4:340–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2003.03038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michna E, Ross EL, Hynes WL, et al. Predicting aberrant drug behavior in patients treated for chronic pain: importance of abuse history. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2004;28:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chelminski PR, Ives TJ, Felix KM, et al. A primary care, multi-disciplinary disease management program for opioid-treated patients with chronic non-cancer pain and a high burden of psychiatric comorbidity. BMC Health Services Research. 2005;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angst MS, Clark JD. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: A qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(3):570–587. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200603000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballantyne JC. Opioid analgesia: perspectives on right use and utility. Pain Physician. 2007 May;10(3):479–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Food and Drug Administration. FDA to Meet with Drug Companies about REMS for Certain Opioid Drugs. http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/opioids/default.htm.

- 25.Banks SM, Kerns RD. Explaining high rates of depression in chronic pain: a diathesis-stress framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119(1):95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sareen J, Jacobi F, Cox BJ, Belik SL, Clara I, Stein MB. Disability and poor quality of life associated with comorbid anxiety disorders and physical conditions. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(19):2109–2116. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gureje O, Simon GE, Von Korff M. A cross-national study of the course of persistent pain in primary care. Pain. 2001;92(1-2):195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00483-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalso E, Allan L, Dellemijn PL, et al. Recommendations for using opioids in chronic non-cancer pain. European Journal of Pain. 2003;7:381–386. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(02)00143-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Breckenridge J, Clark JD. Patient characteristics associated with opioid versus nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug management of chronic low back pain. Journal of Pain. 2003;4(6):344–350. doi: 10.1016/s1526-5900(03)00638-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Zhang L, Unutzer J, Wells KB. Association between mental health disorders, problem drug use, and regular prescription opioid use. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(19):2087–2093. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Unutzer J. Regular use of prescribed opioids: Association with common psychiatric disorders. Pain. 2005;119(1-3):95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turk DC, Okifuji A. What factors affect physicians' decisions to prescribe opioids for chronic noncancer pain patients? Clinical Journal of Pain. 1997;13(4):330–336. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199712000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Fan MY, Devries A, Brennan Braden J, Martin BC. Trends in use of opioids for non-cancer pain conditions 2000-2005 in Commercial and Medicaid insurance plans: the TROUP study. Pain. 2008 Aug 31;138(2):440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braden JB, Fan MY, Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Sullivan MD. Trends in Use of Opioids by Noncancer Pain Type 2000-2005 Among Arkansas Medicaid and HealthCore Enrollees: Results From the TROUP Study. J Pain. 2008 Jul 26; doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips DM. JCAHO pain management standards are unveiled. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(7):428–429. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.423b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arkansas Department of Health Human Services Division of Medical Services. Program Overview - State Fiscal Year 2005. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hennessy S, Bilker WB, Weber A, Strom BL. Descriptive analyses of the integrity of a US Medicaid claims database. Pharmacoepidemiology Drug Safety. 2003;12(2):103–111. doi: 10.1002/pds.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM [computer program]. Version.

- 39.U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Scheduling. [February 24, 2009]; http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/pubs/scheduling.html. [PubMed]

- 40.Fine P, Portenoy RK. A Clinical Guide to Opioid Analgesia. Minneapolis: McGraw-Hill Healthcare Information; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vieweg WV, Lipps WF, Fernandez A. Opioids and methadone equivalents for clinicians. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(3):86–88. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v07n0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain. 5th. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jun 16;352(24):2515–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang PS, Demler O, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Changing profiles of service sectors used for mental health care in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Jul;163(7):1187–1198. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.7.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cannella DT, Lobel M, Glass P, Lokshina I, Graham JE. Factors associated with depressed mood in chronic pain patients: the role of intrapersonal coping resources. Journal of Pain. 2007 Mar;8(3):256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rhudy JL, Dubbert PM, Parker JD, Burke RS, Williams AE. Affective modulation of pain in substance-dependent veterans. Pain Medicine. 2006;7(6):483–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wasan AD, Davar G, Jamison R. The association between negative affect and opioid analgesia in patients with discogenic low back pain. Pain. 2005;117:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strakowski SM, DelBello MP. The co-occurrence of bipolar and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(2):191–206. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Posttraumatic stress disorder and drug disorders: Testing causal pathways. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55(10):913–917. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paulozzi LJ, Budnitz DS, Xi Y. Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006 Sep;15(9):618–627. doi: 10.1002/pds.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trafton JA, Oliva EM, Horst DA, Minkel JD, Humphreys K. Treatment needs associated with pain in substance use disorder patients: implications for concurrent treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004 Jan 7;73(1):23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Unutzer J, Hantke M, Powers D, et al. Care management for depression and osteoarthritis pain in older primary care patients: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008 Nov;23(11):1166–1171. doi: 10.1002/gps.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dobscha SK, Corson K, Perrin NA, et al. Collaborative care for chronic pain in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA. 2009 Mar 25;301(12):1242–1252. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katz JN, Barrett J, Liang MH, et al. Sensitivity and positive predictive value of Medicare Part B physician claims for rheumatologic diagnoses and procedures. Arthritis Rheum. 1997 Sep;40(9):1594–1600. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cicero TJ, Shores CN, Paradis AG, Ellis MS. Source of drugs for prescription opioid analgesic abusers: a role for the internet? Pain Med. 2008 Sep;9(6):718–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moreno C, Laje G, Blanco C, Jiang H, Schmidt AB, Olfson M. National trends in the outpatient diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in youth. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;64(9):1032–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.9.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]