A chemotaxis response regulator CheY3 from V. cholerae has been cloned, overexpressed, purified and crystallized. The crystals of CheY3 diffracted to 1.86 Å resolution.

Keywords: chemotaxis, Vibrio cholerae, flagellar rotation

Abstract

Vibrio cholerae is the aetiological agent of the severe diarrhoeal disease cholera. This highly motile organism uses the processes of motility and chemotaxis to travel and colonize the intestinal epithelium. Chemotaxis in V. cholerae is far more complex than that in Escherichia coli or Salmonella typhimurium, with multiple paralogues of various chemotaxis genes. In contrast to the single copy of the chemotaxis response-regulator protein CheY in E. coli, V. cholerae contains four CheYs (CheY1–CheY4), of which CheY3 is primarily responsible for interacting with the flagellar motor protein FliM, which is one of the major constituents of the ‘switch complex’ in the flagellar motor. This interaction is the key step that controls flagellar rotation in response to environmental stimuli. CheY3 has been cloned, overexpressed and purified by Ni–NTA affinity chromatography followed by gel filtration. Crystals of CheY3 were grown in space group R3, with a calculated Matthews coefficient of 2.33 Å3 Da−1 (47% solvent content) assuming the presence of one molecule per asymmetric unit.

1. Introduction

The ability of motile bacteria to swim towards or away from specific environmental stimuli in order to provide cells with a survival advantage is called chemotaxis (Block et al., 1983 ▶). Signal transduction in chemotaxis has been best studied in Escherichia coli (Armitage, 1999 ▶; Falke et al., 1997 ▶; Stock & Surette, 1996 ▶). Central to the pathway of chemotaxis is a two-component regulatory system that consists of a histidine kinase CheA and a response regulator CheY. When coupled with the methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein MCP, CheA phosphorylates itself and transfers a phosphate group to CheY (Gegner et al., 1992 ▶). Binding of phosphoryl-CheY to the flagellar motor protein FliM induces its clockwise rotation, in contrast to its normal counterclockwise rotation, resulting in reorientation of the cell and hence an abrupt change in its swimming direction (Bren & Eisenbach, 2001 ▶).

The Gram-negative highly motile non-invasive bacterium Vibrio cholerae is the aetiological agent of the severe diarrhoeal disease cholera. This highly motile organism uses the processes of motility and chemotaxis to travel from the lumen of the small intestine to its preferred intestinal niche on the intestinal epithelium and to colonize and produce toxins (Butler & Camilli, 2004 ▶).

Chemotaxis in V. cholerae is far more complex than that in Escherichia coli or Salmonella typhimurium, with multiple paralogues of various chemotaxis genes. The genome sequence of V. cholerae El Tor predicts that the bacterium has three sets of Che proteins and 45 MCP-like proteins (Heidelberg et al., 2000 ▶). Each set of che genes forms clusters as follows: che cluster I contains cheY1 (VC1395), cheA1 (VC1397), cheY2 (VC1398), cheR1 (VC1399), cheB1 (VC1401) and the putative gene cheW (VC1402), cluster II contains cheW1 VC2059), cheB2 (VC2062), cheA2 (VC2063), cheZ (VC2064) and cheY3 (VC2065), and cluster III contains cheB3 (VCA1089), cheD (VCA1090), cheR3 (VCA1091), cheW2 (VCA1093), cheW3 VCA1094), cheA3 (VCA1095) and cheY4 (VCA1096). Clusters I and II are located on chromosome I, and cluster III is located on chromosome II.

Several lines of evidence have suggested that at least some of the chemotaxis-related genes are involved in virulence (Butler & Camilli, 2004 ▶). Furthermore, some chemotactic genes may be required in cholera-toxin production or ToxT up-regulation upon infection in mice (Lee et al., 2001 ▶). The V. cholerae genome contains four chemotaxis-related response regulators CheY1, CheY2, CheY3 and CheY4 and recent studies have strongly indicated that these four CheYs are sufficiently different from each other and are not simply redundant versions of one CheY protein (Boin et al., 2004 ▶).

Although motility and chemotaxis both influence the infectivity of V. cholerae (Gardel & Mekalanos, 1996 ▶; Postnova et al., 1996 ▶), the role of chemotaxis proteins in V. cholerae pathogenesis is less well understood. Attempts to identify the V. cholerae cheY gene that is responsible for the motion of the flagellum showed that insertional disruption of the cheY4 gene results in decreased motility, while insertional duplication of this gene increases motility (Banerjee et al., 2002 ▶). In contrast, another study showed that a deletion mutant of cheY3 impairs chemotaxis (Butler & Camilli, 2004 ▶). An in vivo study reported that only CheY3 directly switches the flagellar rotation by interacting with the ‘switch complex’ protein FliM of the flagellar motor (Hyakutake et al., 2005 ▶). A comparative modelling and simulation study indicated that although all four response regulators can be phosphorylated only CheY3 possesses the key structural elements that are required for FliM binding (Dasgupta & Dattagupta, 2008 ▶).

Considering the emerging importance of the multiple chemotaxis response regulators of V. cholerae in the processes of motility and virulence, we have taken the initiative in determination of the structure of CheY3 from V. cholerae strain O395. Here, we report the cloning, overexpression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray structure analysis of CheY3.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cloning, expression and purification of CheY3

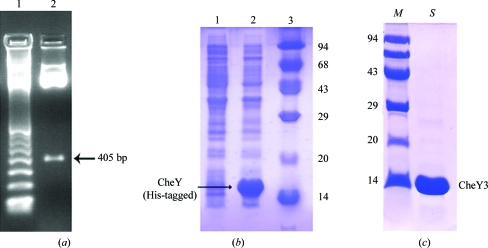

CheY3 was primarily cloned in pGEMT-Easy T/A cloning vector with ampicillin resistance using the primers forward, 5′-GCGGCAT ATGGTGGAGGCAATTTTGAATAA-3′, and reverse, 5′-CGCCGGATCCTTATAAACGCTCAAAAATTTTGTC-3′. The primers were synthesized (NeuProCell) with NdeI and BamHI restriction-enzyme sites (bold). Chromosomal DNA of V. cholerae strain O395 was used as a template to amplify the region encoding cheY3. The cheY3-pGEMT clone was double-digested with the restriction enzymes NdeI and BamHI and the resulting 405 bp fragment (Fig. 1 ▶ a) was purified from 1.5% agarose gel using a gel-extraction kit (Qiagen). This fragment was then subcloned in a pET28a+ vector (Novagen) for overexpression. The clones were selected appropriately using E. coli XL1-Blue cells with kanamycin resistance. CheY3 protein was finally overexpressed (Fig. 1 ▶ b) in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells in the presence of kanamycin as a fusion protein with a 6×His tag at the N-terminus followed by a thrombin cleavage site.

Figure 1.

(a) Confirmation of the CheY3 clone by restriction digestion with NdeI and BamHI, showing a band at 405 bp. Lane 1, 100 bp ladder; lane 2, CheY3 clone. (b) Overexpression of His-tagged CheY3 showing uninduced and induced lanes (1 and 2, respectively) together with molecular-weight markers (lane 3; labelled in kDa) on 15% SDS–PAGE. (c) The homogeneity of the purified CheY3 was checked by 15% SDS–PAGE. CheY3 is shown in lane S; lane M contains molecular-weight markers (kDa).

For overexpression, a single colony was picked, transferred into 100 ml LB broth and grown overnight. 1 l LB broth was inoculated with 10 ml overnight culture and the culture was grown at 310 K until the OD600 reached 0.6. The cells were then induced using 0.1 mM IPTG. After induction at 310 K for 3 h, the cells were harvested at 4500g for 20 min and the pellet was resuspended in 25 ml ice-cold lysis buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 and 300 mM NaCl. PMSF (final concentration of 1 mM) and 10 mg lysozyme were added to the resuspended solution and it was lysed by sonication on ice. The cell lysate was then centrifuged (12 000g for 50 min) at 277 K and 6×His-tagged CheY3 was isolated from the supernatant using Ni–NTA-based immobilized metal-ion affinity chromatography (Qiagen). The 6×His-tagged CheY3 protein was eluted with lysis buffer containing 150 mM imidazole (Sigma). The purity of the eluted fractions was checked by 15% SDS–PAGE; they were found to be nearly homogeneous. The eluted 6×His-tagged CheY3 protein was dialyzed overnight against thrombin cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl), concentrated using an Amicon ultracentrifugation unit (molecular-weight cutoff 3000 Da) and the 6×His tag was cleaved with 1 U thrombin by overnight incubation at 277 K. The protein was further purified by gel filtration using a Sephacryl S-100 (GE Healthcare) column (78 × 1.4 cm) pre-equilibrated with thrombin cleavage buffer containing 0.02% sodium azide at 277 K. The homogeneity of the purified protein was checked using 15% SDS–PAGE (Fig. 1 ▶ c).

2.2. Crystallization

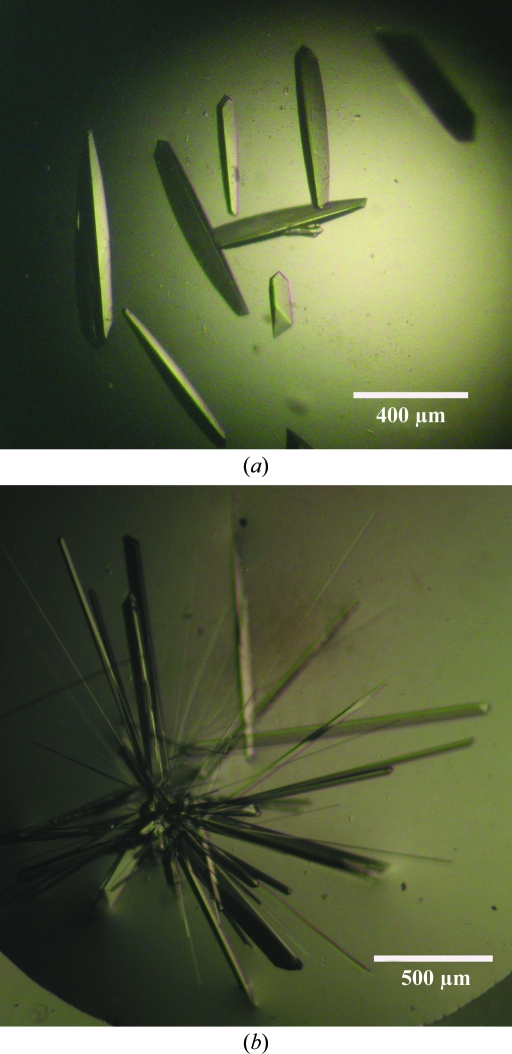

For crystallization, CheY3 in buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl was concentrated to 12 mg ml−1 using an Amicon ultracentrifugation unit (molecular-weight cutoff 3000 Da). Crystallization was performed by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method using 24-well crystallization trays (Hampton Research, Laguna Niguel, California, USA). Grid Screen Ammonium Sulfate, Crystal Screen and Crystal Screen 2 from Hampton Research (Jancarik & Kim, 1991 ▶) were used to explore the initial crystallization conditions. Typically, 2 µl protein solution (12 mg ml−1) was mixed with an equal volume of screening solution and equilibrated over 600 µl of the latter as reservoir solution. CheY3 crystallized in two different conditions: a high-salt condition containing ammonium sulfate and a low-salt condition containing PEG 6000. Both promising crystallization conditions were further optimized. For the high-salt condition the best crystals (0.5 × 0.15 × 0.15 mm; Fig. 2 ▶ a) were obtained when 2 µl protein solution was mixed with an equal volume of precipitant solution consisting of 0.8 M ammonium sulfate in 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.0 (or 0.1 M Tris–HCl buffer pH 8.0) and equilibrated against a reservoir solution consisting of 1.6 M ammonium sulfate in 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.0 (or 0.1 M Tris–HCl buffer pH 8.0) at 293 K for 2 d. The prism-shaped crystals thus obtained diffracted to ∼3 Å resolution. A low-salt crystallization condition was also obtained in which 2 µl protein solution was mixed with an equal volume of precipitant solution consisting of 5%(w/v) PEG 6000 in 0.1 M Tris–HCl pH 8.0 and equilibrated for 7 d against 20%(w/v) PEG 6000 in 0.1 M Tris–HCl pH 8.0. This low-salt condition produced rod-shaped crystals (Fig. 2 ▶ b; 0.7 × 0.1 × 0.1 mm) which produced high-resolution diffraction data.

Figure 2.

Crystals of CheY3 grown (a) in the presence of high-salt precipitant solution consisting of 0.8 M ammonium sulfate in 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.0 and (b) in low-salt precipitant solution consisting of 5% PEG 6000 in 0.1 M Tris–HCl pH 8.0.

2.3. Data collection and processing

Crystals of CheY3 were fished out from the crystallization drops using a 10 µm nylon loop, briefly soaked in a cryoprotectant solution consisting of 10%(w/v) PEG 6000, 15%(v/v) glycerol and 100 mM NaCl in 0.1 M Tris pH 8.0 and flash-frozen in a stream of nitrogen (Oxford Cryosystems) at 100 K. A diffraction data set was collected using an in-house MAR Research image-plate detector of diameter 345 mm and Cu Kα radiation generated by a Bruker–Nonius FR591 rotating-anode generator equipped with Osmic MaxFlux confocal optics and operated at 50 kV and 70 mA. Data were processed and scaled using AUTOMAR (http://www.marresearch.com/automar/run.html). Data-collection and processing statistics are given in Table 1 ▶.

Table 1. Data-collection and data-processing parameters for the V. cholerae CheY3 crystal.

Values in parentheses are for the outermost resolution shell.

| Space group | R3 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å) | a = b = 67.98, c = 75.73 |

| Rotation range per image (°) | 0.5 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 30–1.86 (1.93–1.86) |

| No. of molecules per asymmetric unit | 1 |

| Matthews coefficient (VM; Å3 Da−1) | 2.33 |

| Solvent content (%) | 47 |

| No. of observations | 17473 (1566) |

| No. of unique reflections | 10370 (985) |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.2 |

| Completeness (%) | 94.3 (89.3) |

| Redundancy | 1.7 (1.59) |

| Rmerge† (%) | 2.25 (7.99) |

| B factor (Wilson plot; Å2) | 18.88 |

| Average I/σ(I) | 9.7 (5.4) |

R

merge =

, where I

i(hkl) is the observed intensity of the ith measurement of reflection hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean intensity of reflection hkl calculated after scaling.

, where I

i(hkl) is the observed intensity of the ith measurement of reflection hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean intensity of reflection hkl calculated after scaling.

3. Results

The crystals grown in the presence of ammonium sulfate were larger but only diffracted to ∼3 Å resolution, whereas the crystals grown in the presence of PEG 6000 were of very good quality and diffracted to 1.86 Å resolution. However, both crystals belonged to the hexagonal space group R3, with unit-cell parameters a = b = 68.98, c = 75.73 Å. Packing considerations, based on the molecular weight of 14.7 kDa, indicated the presence of one molecule in the asymmetric unit, corresponding to a Matthews coefficient V M (Matthews, 1968 ▶) of 2.33 Å3 Da−1 and a solvent content of 47%. As the crystals grown in the presence of ammonium sulfate diffracted poorly with spot streaking, data collection was not pursued from these crystals. A total of 114 frames were collected from the crystal grown in the presence of PEG 6000 with a crystal-to-detector distance of 150 mm. The exposure time for each image was 2 min and the rotation range per image was maintained at 0.5°. A data set with an overall completeness of 94.3% was obtained to 1.86 Å resolution (Fig. 3 ▶) with an R merge of 2.25%. Although we collected the data set over 57°, the redundancy (1.7) obtained for space group R3 was a little low, presumably because of the presence of ice rings in the diffraction images.

Figure 3.

X-ray diffraction image of the CheY3 crystal grown under low-salt conditions; the crystal diffracts to a highest resolution of 1.86 Å.

A BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990 ▶) search for a homologous structure showed that CheY from S. typhimurium has the highest identity (66%) to V. cholerae CheY3. Therefore, the coordinates of the Mg2+-bound structure of S. typhimurium CheY (PDB code 2che; Stock et al., 1993 ▶) was used as a search model in molecular-replacement (MR) calculations using MOLREP from the CCP4 package (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4, 1994 ▶). Before proceeding with MR calculations, two residues from the N-terminus, three residues from the C-terminus, waters and ions were deleted from the coordinates of the search model. Additionally, mismatched residues were truncated to alanine. One molecule of this modified model in the asymmetric unit produced a correlation coefficient of 58% with an R factor of 41% using data between 10 and 4.5 Å resolution. Rigid-body refinement followed by a few cycles of positional refinement with CNS (Brünger et al., 1998 ▶) using data between 10 and 2.8 Å resolution led to an R factor of 37.2% (R free = 39.5%). An electron-density map calculated using this model showed an unambiguous polypeptide chain. Refinement and model building is in progress.

Acknowledgments

JD is grateful to Dr Felix Raj SJ, Principal, St Xavier’s College, Kolkata for his encouragement and constant support. JD and MB are grateful to the members of the crystallography laboratory at SINP for their support and cooperation. JD specially thanks Mr Abhijit Bhattacharyya of SINP for his immense technical support. This work was supported by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research [grant No. 37(1381)/09/EMR-II], Government of India.

References

- Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. (1990). J. Mol. Biol.215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Armitage, J. P. (1999). Adv. Microb. Physiol.41, 229–289. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, R., Das, S., Mukhopadhyay, K., Nag, S., Chakrabortty, A. & Chaudhuri, K. (2002). FEBS Lett.532, 221–226. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Block, S. M., Segall, J. E. & Berg, H. C. (1983). J. Bacteriol.154, 312–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Boin, M. A., Austin, M. J. & Hase, C. C. (2004). FEMS Microbiol. Lett.239, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bren, A. & Eisenbach, M. (2001). J. Mol. Biol.312, 699–709. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brünger, A. T., Adams, P. D., Clore, G. M., DeLano, W. L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Jiang, J.-S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N. S., Read, R. J., Rice, L. M., Simonson, T. & Warren, G. L. (1998). Acta Cryst. D54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Butler, S. M. & Camilli, A. (2004). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 101, 5018–5023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994). Acta Cryst. D50, 760–763.

- Dasgupta, J. & Dattagupta, J. K. (2008). J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.25, 495–503. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Falke, J. J., Bass, R. B., Butler, S. L., Chervitz, S. A. & Danielson, M. A. (1997). Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol.13, 457–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gardel, C. L. & Mekalanos, J. J. (1996). Infect. Immun.64, 2246–2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gegner, J. A., Graham, D. R., Roth, A. F. & Dahlquist, F. W. (1992). Cell, 70, 975–982. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Heidelberg, J. F. et al. (2000). Nature (London), 406, 477–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hyakutake, A., Homma, M., Austin, M. J., Boin, M. A., Hase, C. C. & Kawagishi, I. (2005). J. Bacteriol.187, 8403–8410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jancarik, J. & Kim, S.-H. (1991). J. Appl. Cryst.24, 409–411.

- Lee, S. H., Butler, S. M. & Camilli, A. (2001). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 6889–6894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol.33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Postnova, T., Gómez-Duarte, O. G. & Richardson, K. (1996). Microbiology, 142, 2767–2776. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stock, A. M., Martinez-Hackert, E., Rasmussen, B. F., West, A. H., Stock, J. B., Ringe, D. & Petsko, G. A. (1993). Biochemistry, 32, 13375–13380. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stock, J. B. & Surette, M. G. (1996). Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology, 2nd ed., edited by F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. J. Ingram, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter & H. E. Umbarger, pp. 1103–1129. Washington DC: American Society for Microbiology.