Abstract

Although many fruits such as lemon and orange contain citric acid, little is known about beneficial effects of citric acid on health. Here we measured the effect of citric acid on the pathogenesis of diabetic complications in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Although oral administration of citric acid to diabetic rats did not affect blood glucose concentration, it delayed the development of cataracts, inhibited accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) such as Nε-(carboxyethyl)lysine (CEL) and Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine (CML) in lens proteins, and protected against albuminuria and ketosis . We also show that incubation of protein with acetol, a metabolite formed from acetone by acetone monooxygenase, generate CEL, suggesting that inhibition of ketosis by citric acid may lead to the decrease in CEL in lens proteins. These results demonstrate that the oral administration of citric acid ameliorates ketosis and protects against the development of diabetic complications in an animal model of type 1 diabetes.

Keywords: Advanced glycation end-product (AGEs), Nε-(carboxyethyl)lysine (CEL), cataract, diabetes, ketosis, nephropathy

Introduction

A wide range of drugs is used for the treatment of diabetes and its complications, including inhibitors of aldose reductase, protein kinase C, and glutamine fructose aminotransferase, inhibitors and breakers of advanced glycation end-product (AGEs) [1], inhibitors of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) [2], and the chelator, trientine [3]. While the therapeutic merits of chelators for treatment of diabetes are not as well studied, there is evidence that AGE inhibitors and breakers [4], as well as ACE inhibitors and ARBs [5, 6], have strong chelating activity. Other drugs used for treatment of diabetes have amino, carboxyl and other nucleophilic functional groups and probably also have mild chelating activity, which could contribute to their effectiveness in treating diabetes and its complications.

In this study we have explored the effects of citric acid on metabolic changes and development of complications in diabetes. Citrate, a natural, dietary chelator found in citrus fruits [7], is widely used in food products as a preservative and to enhance tartness. We set out to examine the effects of dietary citrate on formation of AGEs, especially glycoxidation products, such as Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine (CML) and Nε-(carboxyethyl)lysine (CEL), which require metal-catalyzed oxidative reactions for their formation from glycation adducts. As we show here, citrate inhibited the development of cataracts and nephropathy and the formation of both CML and CEL in the lens of streptozotocin-induced (type 1) diabetic rats. Because citrate was a slightly more effective inhibitor of CEL formation, we examined the effects of citrate on formation of CEL from two precursors, methylglyoxal, a degradation product of triose phosphates, and acetol, a metabolite of the ketone body acetone. As shown below, we also observed that citrate inhibited development of ketoacidosis in diabetic rats. Overall, our observations suggest that citrate may contribute to the health benefits of fresh fruits in the diet of diabetic patients and that citrate supplementation may be helpful in the management of diabetes and its complications.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Fatty acid-free human serum albumin (HSA), glucose test kit (Glucose CII-Test WAKO), citric acid monohydrate, acetoacetic acid, β-hydroxybutyric acid, acetone and acetol were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Inc. (Osaka, Japan). Streptozotocin (STZ) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG antibody was purchased from Kirkegaard Perry Laboratories (Gaitherburg, MD, USA). All other chemicals were of the best grade available from commercial sources.

Animal studies

The experimental protocol was approved by the ethics review committee of Kumamoto University for animal experimentation. Wistar rats were purchased from SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). These rats were housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility (12 h/12h light/dark cycle) and were fed a normal rodent chow diet (Clea, Japan). Diabetes was induced in 8-week-old male rats (weight ~225 g) by a single intravenous (tail vein) injection of STZ (45 mg/kg body weight) in 200 µL of 0.05 M saline-citrate buffer (pH 4.5). Age-matched control rats were given intravenous injections of 200 µL of 0.05 M saline-citrate buffer (pH 4.5) alone. One week after induction of diabetes (blood glucose ≥ 250 mM), rats were divided randomly into an untreated diabetic group (n = 8) and two treated diabetic groups (n = 6), receiving citric acid (2 g/l) in the drinking water, or insulin therapy. Insulin -treated rats received 3 IU of neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin (Novo Nordisk Pharma, Tokyo, Japan) three times per week; this was increased to 5 IU after week 15 to adjust for the increase in body weight as described previously [8]. Fasting (12 hr) blood samples were obtained from the tail vein two days after insulin injection for measurement of blood glucose, HbA1c and ketone bodies. The animals were killed under pentobarbital anesthesia at 27 weeks after injection of STZ. Blood samples were analyzed for HbA1c by Olympus AU600 automatic analyzer (Beckman Coulter Inc., CA, USA) using monoclonal anti-hemoglobin A1c antibody (Kyowa Medix Co. Ltd. Tokyo, Japan) and total ketone bodies, acetoacetic acid and β-hydroxybutyric acid were measured on an JCA-BM 8000 automatic analyzer (Japan Electron Optics Laboratories, Tokyo) using standard, NAD(H)-linked enzymatic methods. Progression of nephropathy was assessed by measurements of 24-h urinary albumin and total protein excretion. For urine collections, rats were housed in metabolic cages for 24 h. Urinary albumin was quantified using the rat albumin ELISA quantitation kit (Bethyl Laboratories, Texas, USA). Total urinary protein was measured using the microprotein-pyrogallol red kit (Sigma-Aldrich), as described previously [8].

Evaluation of cataractogenesis and AGEs formation

Rat lenses were removed and backscattering of light was evaluated on a grid sheet, as described previously [9]. Each lens sample was homogenized in 1 mL of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffered saline (PBS) in the presence of 1 mM diethylaminetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan), and protein concentration was measured by the bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) assay (Pierce, IL).

Measurement of AGEs by gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and amino acid analysis

The lens content of CML and CEL was analyzed by GC-MS/MS on a TSQ 7000 instrument (Thermo-Finnigan, Waltham, MA), as described previously [10]. Briefly, following acid hydrolysis, amino acids were converted to their trifluoroacetyl methyl ester derivatives and analyzed by isotope dilution GC-MS/MS using the following parent and daughter ion pairs: 180 > 69 (lysine), 188 > 69 (d8-lysine); 392 > 192 (CML), 396 > 196 (d4-CML); 379 > 206 (CEL); 387 > 214 (d8-CEL), as described previously [10]. CML and CEL were also measured in albumin incubated with ketone bodies in vitro (see below) by amino acid analysis after acid hydrolysis with 6 N HCl for 24 hr at 110°C, using a Hitachi L-8500A amino acid analyzer Tokyo, Japan) equipped with cation exchange column (#2622 SC, 4.6 × 80 mm, Hitachi), as described previously [11].

Incubation of ketone bodies and acetol with HSA

Acetoacetic acid, β-hydroxybutyric acid, acetone, acetol and methylglyoxal (each 100 mM) were incubated with HSA (2 mg/mL) in 200 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, for 1 week at 37°C. Each sample was dialyzed against PBS at 4°C for 12 hrs, then protein concentration was measured by the BCA method. Formation of CEL in these samples was determined by ELISA as described below.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for CEL

For non-competitive ELISA [12], each well of a 96-well microtiter plate was coated with 100 µl of the indicated concentration of samples in PBS, and incubated for 2 hr. The wells were washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (buffer A). The wells were then blocked with 0.5% gelatin in PBS for 1 hr. After triplicate washing with buffer A, the wells were incubated for 1 hr with 100 µl of anti-CEL antibody (CEL-SP) (1 µg/ml) [12]. After triplicate washing with buffer A, the wells were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (0.2 µg/ml), followed by a reaction with 1, 2-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride. The reaction was terminated by sulfuric acid (1.0 M), and the absorbance was read at 492 nm on a micro-ELISA plate reader.

Statistical Analysis

All experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD. Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance using the Student’s t- test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Newman-Keuls post-hoc test.

Results

Changes in body weight and fasting blood glucose concentrations

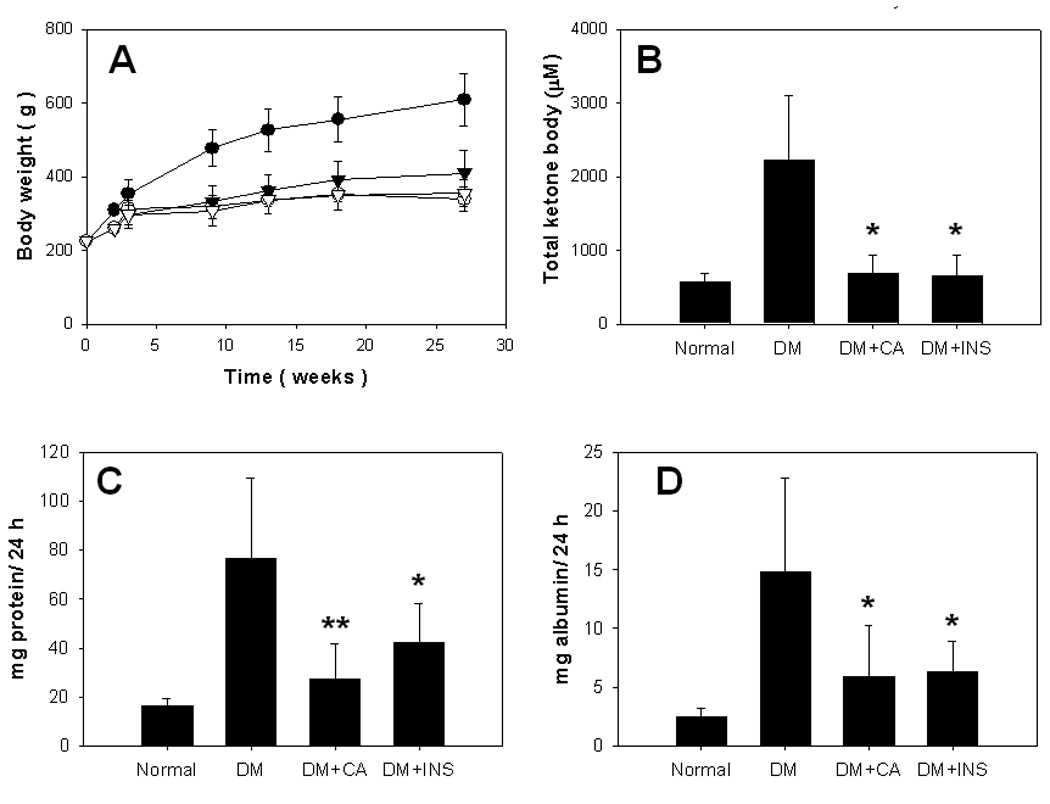

Normal rats increased from ~200 to ~600 g during the course of the 27 week study, while diabetic rats grew to ~400 g (Fig. 1A). Neither CA nor insulin, at the doses administered, significantly affected the weight gain of diabetic animals. In separate studies we determined that although blood glucose concentration was decreased acutely by the administration of insulin, glucose concentration returned to the levels observed in untreated diabetic controls by 24 h after insulin injection. Thus, %HbA1c was not significantly different between diabetic control and insulin-treated animals. In contrast, both citric acid and insulin significantly reduced total ketone body concentration by ~70% at 24 hr after insulin injection (Fig. 1B). The treatment of citric acid or insulin to diabetic animals restored the total ketone body concentrations to normal level, with no statistically significant differences between the groups (P < 0.3 between groups).

Fig. 1. Changes in body weight and clinical parameters.

Control and diabetic rats were maintained for 27 weeks. Body weight (A) of normal (closed circle), diabetic control (DM) (open triangle), diabetic with insulin therapy (closed circle) and diabetic with citric acid (open circle) was measured continuously, and ketone bodies (B) were measured at the end of the study. Progression of nephropathy was assessed by measurements of 24-h urinary total protein (C) and albumin (D) excretion at 27 weeks. Data are mean±SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 vs diabetic control (DM) group.

Urinary protein and albumin

Urinary protein and albumin concentrations were used to evaluate effects on renal function. Total 24-h urinary protein and albumin concentrations at 27 weeks were approximately 5 and 6 times higher, respectively, in diabetic control animals compared with non-diabetic animals. Both citric acid and insulin therapy significantly decreased urinary protein and albumin concentration at 27 weeks (Fig. 1C and 1D).

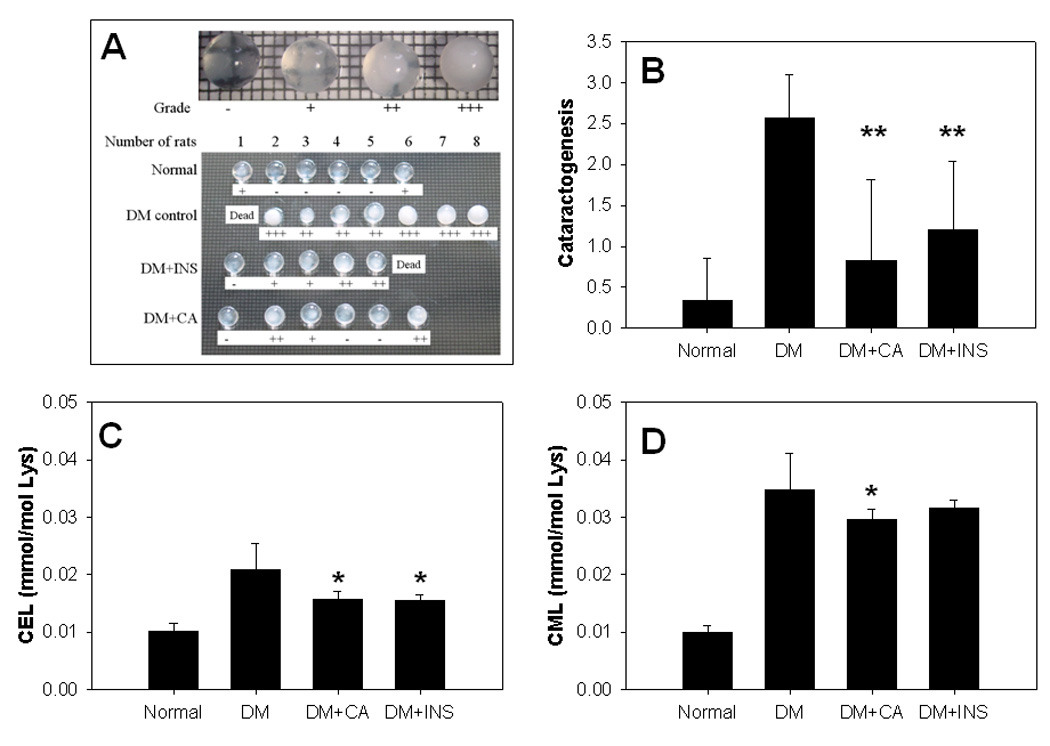

Cataractogenesis and AGEs accumulation in lens proteins

We next measured the effects of citric acid and insulin on cataractogenesis. Cataracts were graded on a to scale, as described previously [9]. Both insulin and citric acid significantly inhibited the progression of cataracts (Fig. 2A and 2B). Since post-translational modification of crystallins by AGEs is thought to underlie the crosslinking and insolubilization of lens protein and development of cataracts, we next measured the effect of administration of citric acid and insulin on AGE accumulation in lens proteins. As shown in Fig. 2C, both citric acid and insulin significantly inhibited the accumulation of CEL; similar results were observed for CML, although insulin, at the dose used, was less effective (p=0.09 vs diabetic control) in inhibiting the accumulation of CML (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2. Cataractogenesis and AGEs accumulation in lens proteins.

Rat lenses were removed from eye balls and backscattering of light was determined by putting the lenses on a grid sheet (A), and the progression of cataract was compared in each group (B). The contents of CEL (C) and CML (D) in lenses were analyzed by GC-MS/MS as described in materials and methods. Data are mean±SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 vs diabetic control (DM) group.

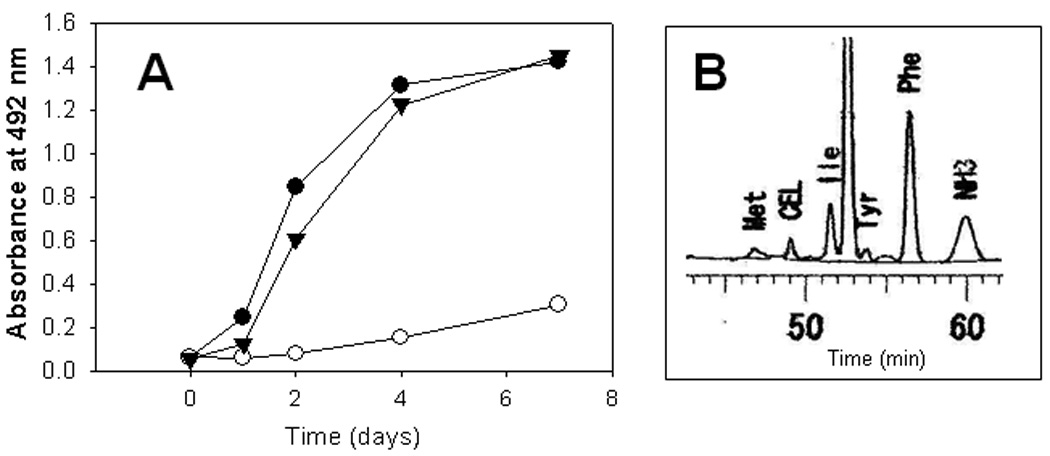

Formation of CEL from the metabolite of ketone body

Because ketone bodies in blood, and CEL and CML in lens proteins were decreased by administration of citric acid, we considered the possibility that ketone bodies or their metabolites might generate these AGEs. As shown in Fig. 3A, although CML was not detectable, CEL was generated during incubation of HSA with acetol, which is formed in vivo during acetone metabolism by acetone monooxygenase; this reaction was inhibited by DTPA, indication a requirement for oxidation (glycoxidation) during the reaction of acetol with albumin to form CEL. In contrast, citrate did not inhibit formation of CEL from acetol (Fig. 3A), suggesting that inhibition of ketogenenesis and ketonemia, rather than chelation of metal ions, was the primary mechanism of inhibition of AGE formation in the lens. Amino acid analysis demonstrated that 3.8 mol CEL/HSA was observed in acetol-modified HSA (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the primary ketone bodies, acetoacetic acid, β-hydroxybutyric acid and acetone, failed to generate either CML of CEL (data not shown).

Fig. 3. Formation of CEL from the metabolite of ketone body.

Formation of CEL during incubation of HSA with acetol was determined by ELISA (A) in the presence of DTPA (open circle), citric acid (triangle) or absence of interventions (closed circle). CEL content was also measured by HPLC (B) as described in materials and methods.

Discussion

Blood glucose concentration is elevated in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, while ketone bodies, which are indicators of excessive fat metabolism, are generally elevated only in poorly controlled type 1 diabetes. Under these circumstances, total ketone bodies may exceed 10 mmol/l, while those of normal subjects are less than 0.5 mmol/l [13]. Ketoacidosis is a major complication of Type I diabetes, and also enhances endogenous AGE formation by stimulating nitric oxide (NO) release from vascular endothelial cells [14], oxygen radical formation and lipid peroxidation [15]. Diabetic patients with frequent episodes of ketoacidosis suffer from increased incidences of vascular diseases, morbidity and mortality [16].

In the present study, citrate was administered to type 1 diabetic rats at a dose (2 g/L in drinking water), commonly used for AGE inhibitors, such as aminoguanidine (AG) and pyridoxamine (PM) [17]. Although we did not measure serum citrate concentration, citrate is resorbed in the kidney [18], and thus the therapeutic effects of citrate are likely to be prolonged, compared to AGE inhibitors. Like AG and PM [17], citrate inhibited development of nephropathy (albuminuria) in the diabetic rat (Fig. 1C and 1D). Similarly, as observed with AG [19] and PM [20], citrate delayed the onset of cataracts (Fig. 2A and 2B) and also inhibited formation of AGEs in the lens (Fig. 2C and 2D).

In addition to these effects, citrate significantly reduced ketoemia in the diabetic rat (Fig. 1B). This is not surprising since metabolism of citrate produces oxaloacetate, which uses, rather than produces, acetyl-CoA. The anti-ketotic effects of citrate (and oxalate) were reviewed by Krebs in 1960 [21], and Fasella et al. [22] reported in 1958 that citrate, administered by intravenous injection to alloxan-diabetic rats, had a mild, but not statistically significant anti-ketotic effect; while more significant effects were observed in diet-induced ketonemia.

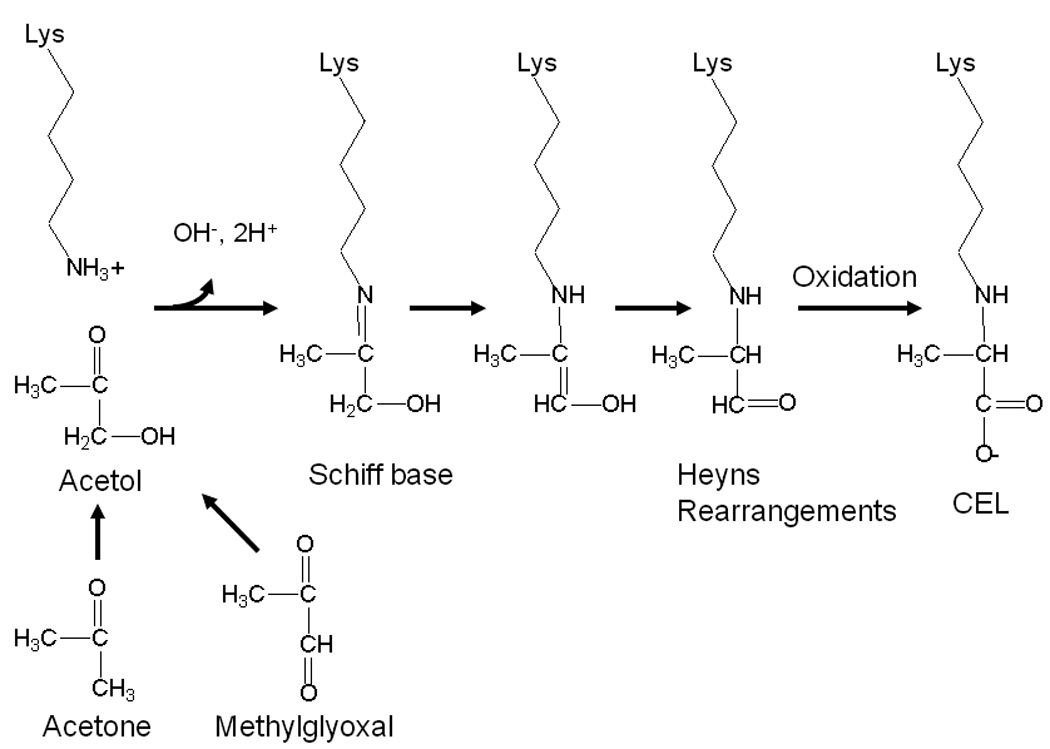

Since the administration of citric acid did not affect blood glucose or HbA1c concentrations, but did decrease lens AGEs and plasma ketone bodies, we examined the effects of citrate on formation of CEL and CML in vitro. Although the ketone bodies, acetoacetic acid, β-hydroxybutyric acid and acetone, did not generate CEL (data not shown), acetol, a metabolite of both acetone and methylglyoxal (Fig. 4) [23], reacted with protein to produce CEL (Fig. 3); this reaction occurred only under oxidative conditions, i.e. it was inhibited by DTPA, consistent with the mechanism proposed in Fig. 4. Since citrate did not directly inhibit formation of CEL from acetol (Fig. 3A), these results suggest that inhibition of CEL formation by citric acid may be secondary to the inhibition of ketogenesis. Our results demonstrate that acetol modifies proteins to form CEL, and also indicate that citrate, which is an effective chelator of calcium, copper and iron at physiological pH, does not inhibit this metal-catalyzed glycoxidation reactions. Further studies are required to examine the effects of citrate on other glycoxidation and lipoxidation reactions.

Fig. 4.

Possible pathway of CEL formation during incubation of protein with acetol

Since life-style related diseases such as atherosclerosis and diabetes progress gradually due to poor dietary habits, improvement of daily nutrition is a recommended as a first line of defense against the pathogenesis of these diseases. Our results suggest that daily intake of citric acid from many fruits such as lemons, limes and oranges, and possibly as a supplement, can thus play a beneficial role in limiting ketosis and the progression of diabetic complications. Other diseases complicated by ketosis, such as ketotic hypoglycemia of childhood, corticosteroid or growth hormone deficiency, intoxication with alcohol or salicylates, and several inborn errors of metabolism [24] may also benefit from diets rich in citrus fruits or from citrate supplementation.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for scientific Research (No. 18790619 to Ryoji Nagai) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Cultures of Japan and by NIH Research Grant DK-19971 (to John W Baynes).

Abbreviations

- AGEs

advanced glycation endproducts

- CEL

Nε-(carboxyethyl)lysine

- CML

Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine

- INS

insulin

- CA

citric acid

References

- 1.Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54:1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calcutt NA, Cooper ME, Kern TS, Schmidt AM. Therapies for hyperglycaemia-induced diabetic complications: from animal models to clinical trials. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:417–429. doi: 10.1038/nrd2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper GJ, Young AA, Gamble GD, Occleshaw CJ, Dissanayake AM, Cowan BR, Brunton DH, Baker JR, Phillips AR, Frampton CM, Poppitt SD, Doughty RN. A copper(II)-selective chelator ameliorates left-ventricular hypertrophy in type 2 diabetic patients: a randomised placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia. 2009;52:715–722. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price DL, Rhett PM, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. Chelating activity of advanced glycation end-product inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48967–48972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108196200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wihler C, Schafer S, Schmid K, Deemer EK, Munch G, Bleich M, Busch AE, Dingermann T, Somoza V, Baynes JW, Huber J. Renal accumulation and clearance of advanced glycation end-products in type 2 diabetic nephropathy: effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme and vasopeptidase inhibition. Diabetologia. 2005;48:1645–1653. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1837-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyata T, van Ypersele de Strihou C, Ueda Y, Ichimori K, Inagi R, Onogi H, Ishikawa N, Nangaku M, Kurokawa K. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors lower in vitro the formation of advanced glycation end products: biochemical mechanisms. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2478–2487. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000032418.67267.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penniston KL, Nakada SY, Holmes RP, Assimos DG. Quantitative assessment of citric acid in lemon juice, lime juice, and commercially-available fruit juice products. J Endourol. 2008;22:567–570. doi: 10.1089/end.2007.0304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alderson NL, Chachich ME, Frizzell N, Canning P, Metz TO, Januszewski AS, Youssef NN, Stitt AW, Baynes JW, Thorpe SR. Effect of antioxidants and ACE inhibition on chemical modification of proteins and progression of nephropathy in the streptozotocin diabetic rat. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1385–1395. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1474-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong X, Ayala M, Lofgren S, Soderberg PG. Ultraviolet radiation-induced cataract: age and maximum acceptable dose. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1150–1154. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagai R, Brock JW, Blatnik M, Baatz JE, Bethard J, Walla MD, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW, Frizzell N. Succination of protein thiols during adipocyte maturation: a biomarker of mitochondrial stress. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34219–34228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagai R, Fujiwara Y, Mera K, Yamagata K, Sakashita N, Takeya M. Immunochemical detection of Nepsilon-(carboxyethyl)lysine using a specific antibody. J Immunol Methods. 2008;332:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagai R, Hayashi CM, Xia L, Takeya M, Horiuchi S. Identification in human atherosclerotic lesions of GA-pyridine, a novel structure derived from glycolaldehyde-modified proteins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48905–48912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205688200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lebovitz HE. Diabetic ketoacidosis. Lancet. 1995;345:767–772. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90645-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avogaro A, Calo L, Piarulli F, Miola M, deKreutzenberg S, Maran A, Burlina A, Mingardi R, Tiengo A, Del Prato S. Effect of acute ketosis on the endothelial function of type 1 diabetic patients: the role of nitric oxide. Diabetes. 1999;48:391–397. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain SK, McVie R. Hyperketonemia can increase lipid peroxidation and lower glutathione levels in human erythrocytes in vitro and in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 1999;48:1850–1855. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.9.1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vignati L. Insulin pumps: when are they indicated, what can they do? Trans Assoc Life Insur Med Dir Am. 1985;68:53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Degenhardt TP, Alderson NL, Arrington DD, Beattie RJ, Basgen JM, Steffes MW, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. Pyridoxamine inhibits early renal disease and dyslipidemia in the streptozotocin-diabetic rat. Kidney Int. 2002;61:939–950. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pajor AM. Citrate transport by the kidney and intestine. Semin Nephrol. 1999;19:195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swamy-Mruthinti S, Green K, Abraham EC. Inhibition of cataracts in moderately diabetic rats by aminoguanidine. Exp Eye Res. 1996;62:505–510. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padival S, Nagaraj RH. Pyridoxamine inhibits maillard reactions in diabetic rat lenses. Ophthalmic Res. 2006;38:294–302. doi: 10.1159/000095773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krebs H. Biochemical aspects of ketosis. Proc R Soc Med. 1960;53:71–80. doi: 10.1177/003591576005300201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fasella P, Turano C, Baglioni C, Siliprandi N. Action of citrate and oxalacetate on dietary and diabetic ketosis. Lancet. 1958;1:1097. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(58)91850-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dhar A, Desai K, Kazachmov M, Yu P, Wu L. Methylglyoxal production in vascular smooth muscle cells from different metabolic precursors. Metabolism. 2008;57:1211–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell GA, Kassovska-Bratinova S, Boukaftane Y, Robert MF, Wang SP, Ashmarina L, Lambert M, Lapierre P, Potier E. Medical aspects of ketone body metabolism. Clin Invest Med. 1995;18:193–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]