Abstract

Background

We hypothesized that gp91phox (NOX2), a subunit of NADPH oxidase, generates superoxide anion (O2-) and has a major causative role in traumatic brain injury (TBI). To evaluate the functional role of gp91phox and reactive oxygen species (ROS) on TBI, we carried out controlled cortical impact in gp91phox knockout mice (gp91phox-/-). We also used a microglial cell line to determine the activated cell phenotype that contributes to gp91phox generation.

Methods

Unilateral TBI was induced in gp91phox-/- and wild-type (Wt) mice (C57/B6J) (25-30 g). The expression and roles of gp91phox after TBI were investigated using immunoblotting and staining techniques. Levels of O2- and peroxynitrite were determined in situ in the mouse brain. The activated phenotype in microglia that expressed gp91phox was determined in a microglial cell line, BV-2, in the presence of IFNγ or IL-4.

Results

Gp91phox expression increased mainly in amoeboid-shaped microglial cells of the ipsilateral hemisphere of Wt mice after TBI. The contusion area, number of TUNEL-positive cells, and amount of O2- and peroxynitrite metabolites produced were less in gp91phox-/- mice than in Wt. In the presence of IFNγ, BV-2 cells had increased inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitric oxide levels, consistent with a classical activated phenotype, and drastically increased expression of gp91phox.

Conclusions

Classical activated microglia promote ROS formation through gp91phox and have an important role in brain damage following TBI. Modulating gp91phox and gp91phox -derived ROS may provide a new therapeutic strategy in combating post-traumatic brain injury.

Background

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a serious condition in emergency medicine, and its pathophysiological profile is varied and complicated. One of the neurotoxic factors thought to be involved is oxidative stress [1,2]. A large number of studies have reported that oxidative stress, which generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), plays a key role in the development of TBI [1,3,4]. Consequently, one of the most obvious ways to manage TBI may be to control ROS generation [1] given that animal experiments have supported the notion that free radical scavengers and antioxidants dramatically reduce cerebral damage [1,5,6]. The superoxide anion (O2-) is an important free radical, and is the source of other ROS that lead to lipid peroxidation [7]. Cyclooxygenase, xanthine oxidase, and NADPH oxidases of the NOX family are well known generators of O2- in the brain. However, the main cellular mediator of O2- generation after TBI has not yet been determined. NADPH oxidase, a multiunit enzyme initially discovered in neutrophils, has recently emerged as a major generator of ROS in neurons, glial cells and cerebral blood vessels [8-10]. NADPH oxidase is composed of membrane-bound (p22phox and gp91phox) and cytoplasmic subunits (p40phox, p47phox, and p67phox). Several homologs of the catalytic subunit of the enzyme, gp91phox, also termed NOX2, exist (NOX1 through NOX5) [11,12]. It has been reported that gp91phox-containing NADPH oxidase produces a large amount of O2- in leukocytes, while numerous papers have reported on the role for gp91phox in various neurodegenerative conditions [13,14]. However, the source and the roles of gp91phox after TBI have not been established. In this study, we used the gp91phox-/- mouse to investigate the kinetics and the roles of gp91phox following TBI.

Methods

Animals

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Showa University. The gp91phox-/- (C57/B6J) mice are described by Dinauer et al. [15], Wild mice (Wt) were generated from the same chimeric founder, and experiments were performed in age- and weight-matched animals.

Controlled cortical impact model

Mice were anesthetized with 2% sevoflurane in 70% N2O and 30% O2. A controlled cortical impact was made using a pneumatically controlled impactor device as described previously [16].

Cell culture

We used the BV-2 microglial cell line to investigate which microglia cells express gp91phox [17]. This mouse BV-2 cell line was obtained from Interlab Cell Line Collection (Genova, Italy) and cultured in 10% RPMI1640 (RPMI1640 with 10% fetal calf serum [FCS], 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine [all from GIBCO/BRL, Grand Island, NY]). The cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. After harvesting, the cells were washed with PBS twice and resuspended with experimental medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium [GIBCO/BRL] with 1% FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine). The cells were seeded into six-well plates at 1 × 106 cells/well/ml and then exposed to IFNγ (10 ng/ml), IL-4 (20 ng/ml), IL-10 (10 ng/ml, all from Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), or vehicle (n = 3/group). Twenty-four hours later, the cells were collected by centrifugation. The samples were kept at -30°C until analysis.

Western blot analysis

The cerebrum was removed from decapitated animals at 0 (sham-operated), 24, and 48 hours after TBI and divided into the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. These samples were then homogenized in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 0.15 M NaCl and 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EGTA, 50 mM NaF, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM sodium pyrvate, and protease inhibitor cocktail [Sigma, St. Louis, MO]), and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes on ice. BV-2 samples were sonicated for 10 seconds with lysis buffer to prepare cell suspensions.

After determination of the protein concentration (BCA protein assay, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), appropriate amounts of samples were electrophoresed. The separated proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidinene fluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). After blocking with 2% Blockace (DS Pharma, Osaka, Japan), the membranes were probed with primary antibodies. After washing, the membrane was probed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies. The protein bands were detected by chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate; Pierce, Rockford, IL) and exposed onto X-ray film. The films were scanned, and the signal densities were quantified using the UN-SCAN-IT gel analysis program (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT).

Immunohistochemistry

Mice subjected to TBI were placed under pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.) anesthesia and perfused with 0.9% NaCl followed by 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Brains were removed and processed to frozen blocks that were then cut into 8-μm sections (n = 4-5/group).

The sections were incubated with 0.3% H2O2 and then incubated with PBS containing 5% normal horse serum to mask nonspecific reactions. Next, the sections were incubated with antibody raised against gp91phox [18]. One day later, the sections were rinsed and incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and then with an avidin-biotin complex solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) followed by diaminobenzidine (DAB; Vector) as a chromogen.

A similar procedure was used for multiple immunostaining, except that the sections were not incubated with 0.3% H2O2, and were incubated with Alexa-labeled fluorescence secondary antibodies. Primary and secondary antibodies for multiple-staining are listed in Table 1. 4,6-Diamidine-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI, 1:10,000; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was used for nuclear staining. The fluorescence and immunolabeling were detected using a confocal laser microscope (AX-10, Zeiss; Oberkochen, Germany).

Table 1.

Antibodies used for immunoblotting (IB) and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

| Antibody | Antigen | Host | Company | Catalog # | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary antibody (clone #) | |||||

| gp91phox | Human gp91 | Rabbit | See ref 18 | 4,000 (IB) 200 (IHC) |

|

| p22phox | Human p22 | Rabbit | See ref 18 | 3,000 | |

| iNOS | Mouse iNOS | Rabbit | Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY) | N32030 | 10,000 |

| Ym1 | Mouse Ym1 | Rabbit | StemCell Tech (Vancouver, BC, Canada) | 01404 | 1,000 |

| GAPDH (6C5) | Rabbit GAPDH | Mouse | Chemicon International (Temecula, CA) | MAB374 | 3,000 |

| β-Actin (AC-74) | Mouse β-Actin | Mouse | Sigma (St Louise, MO) | A5316 | 4,000 |

| CD11b (5C6) | Mouse CD11b | Rat | Serotec (Oxford, UK) | MCA711 | 500 |

| GFAP (G-A-5) | Mouse GFAP | Mouse | Sigma (St Louise, MO) | G3893 | 1000 |

| NeuN | Mouse NeuN | Mouse | Chemicon International (Temecula, CA) | MAB377 | 1000 |

| 3-NT | Nitrated KLH | Rabbit | Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY) | 06-284 | 100 |

| Secondary antibody (conjugation) | |||||

| Mouse IgG (HRP) | Mouse IgG | Sheep | GE Healthcare Bioscience (Little Chalfont, UK) | NA931 | 2,000 |

| Rabbit IgG (HRP) | Rabbit IgG | Donkey | GE Healthcare Bioscience (Little Chalfont, UK) | NA934 | 3,000 |

| Rabbit IgG (biotinylated) | Rabbit IgG | Goat | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) | SC-2040 | 200 |

| Mouse IgG (Alexa 546) | Mouse IgG | Goat | Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) | A11030 | 400 |

| Rabbit IgG (Alexa 488 or 546) | Rabbit IgG | Goat | Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) | A11034 or 11035 | 400 |

| Rat IgG (Alexa 546) | Rat IgG | Goat | Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) | A11081 | 400 |

Evaluation of the injured brain area

The areas of injured brain were determined using 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining of tissues 48 hours after TBI. The animals were decapitated, and the brain was sectioned into four 2-mm coronal sections by using a mouse brain matrix. The brain slices were then stained with 2% TTC at 37°C for 30 min and photographed on the anterior surface of each section with a scale bar. The areas of injured brain were delineated by examining differences between the ipsilateral and contralateral regions in the center slice of injured brain and measured by using NIH Image software. http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/about.html.

Evaluation of apoptosis-like cell death

To determine neural apoptosis-like cell death, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP end-labeling (TUNEL) staining (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, POD; Roche) was performed 48 hours after TBI (n = 5) and the number of TUNEL-positive cells in the ipsilateral hemisphere was then counted and compared gp91phox-/- with Wt mice in a similar cortical region (40 × magnification).

In situ detection of O2-

Production of O2- was determined by in situ detection of oxidized hydroethidium (HEt) [19]. With the animal placed under anesthesia, the HEt solution was administered (1 mg/mL 0.9% NaCl with 1% DMSO) into the jugular vein (n = 3 per group) 48 hours after TBI. Fifteen minutes later, the brain was removed and frozen in blocks and cryosectioned (8 μm) in the coronal plane. To demonstrate the cellular distribution of Et, the sections were co-stained with antibodies raised against gp91phox, CD11b, GFAP, or NeuN. Fluorescence was detected using confocal laser microscopy (AX-10, Zeiss, Germany)

NO and TNFα measurement in media

Levels of NO and TNFα production are markers of classically activated microglia [20]. NO production was measured using the Griess method (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) as total NO (NO2- and NO3-). TNFα production was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using the Duoset ELISA Development System (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Assay for arginase activity

Arginase is a marker for alternatively activated microglia [20]. Arginase activity was measured according to a previous paper [21] with minor modification. In brief, the cell homogenate was mixed with equal volumes of prewarmed 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 containing 10 mM MnCl2 and incubated for 15 minutes at 55°C. The mixture was incubated in 0.25 M L-arginine for 60 minutes at 37°C to produce urea from arginine and the reactions were stopped by adding Stop solution (H2SO4/H3PO4/H2O, 1:3:7). Then, 1% (final concentration) 1-phenyl-1, 2-propanedione-2-oxime (ISPF) in ethanol was added to the solution, which was heated at 100°C for 45 min. The reaction between urea and ISPF produced a pink color, and absorption was measured at 540 nm.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SE for in vivo experiments. Data are expressed as mean ± SD for in vitro experiments Statistical comparisons were performed using the Student's t tests and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) as appropriate. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Gp91phox is upregulated in the peri-contusional region after traumatic brain injury

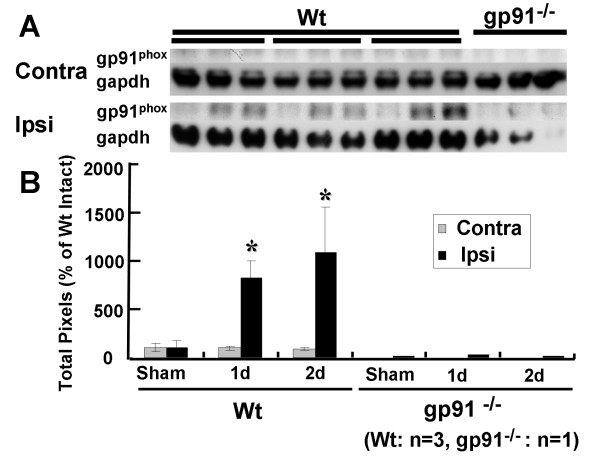

Fig 1 shows the results of immunoblotting experiments to describe the expression of gp91phox after TBI. Protein levels of gp91phox were not increased after TBI in the contralateral hemisphere of Wt mice. In the ipsilateral hemisphere of Wt mice, protein levels of gp91phox were greater at 1 and 2 days after TBI relative to the contralateral hemisphere (Fig 1A, B). The data indicate that gp91phox increased in the ipsilateral hemisphere following TBI stress.

Figure 1.

Characterization of gp91phox after traumatic brain injury (TBI) using western immunoblots. (A) Immunoblotting signals before and after TBI in wild-type (Wt) mice (left) and gp91phox-/- mice (right). (B) In Wt mice, gp91phox levels were significantly increased on day 1 and day 2 after TBI (*p < 0.05 relative to sham). Gp91phox levels on the ipsilateral side were greater than on the contralateral side on day 1 and day 2 after TBI (*p < 0.05). Each value is the mean ± SE (n = 3). Note that the intensity of each sample was quantified and corrected relative to the labeling control, actin. Increasing levels of gp91phox were not seen in gp91phox-/- mice.

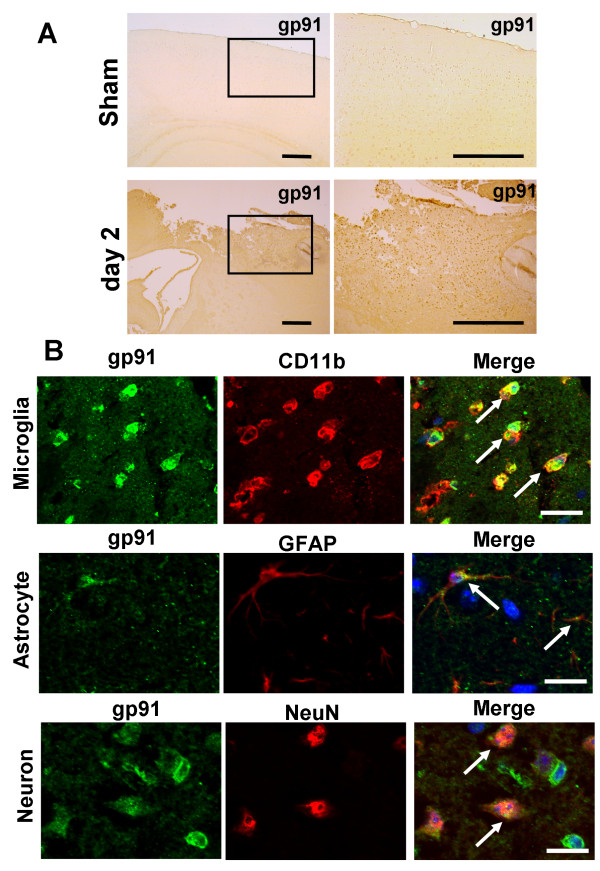

The results of single immunohistochemical detection of gp91phox after TBI are presented Fig 2A. Two days after TBI, gp91phox immunoreactivity was dramatically increased in the peri-contusion region.

Figure 2.

Expressions and cell identification of gp91phox in peri-contusional area after traumatic brain injury (TBI). (A) In sham-operated animals, weak immunoreactivity for gp91phox was observed in the cortex (upper panel). Two days after TBI, gp91phox immunoreactivity was dramatically increased in the peri-contusional area (lower panel). Scale bars = 400 μm. (B) Co-immunostaining of gp91phox with cell markers in the peri-contusional region. Immunostaining was carried out using antibodies for gp91phox (shown in green) together with Integrin alpha M (CD11b) (upper), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (middle), and neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN) (lower). Microglia, astrocyte, and neuron markers are shown in red. Gp91phox immunoreactive cells were co-labeled with all cell markers. Particularly strong expression of gp91phox was detected in microglial-like cells (CD11b-positive cells). Cells were counter-stained with DAPI to show nuclei (blue). Scale bars = 20 μm.

Gp91phox is mainly expressed by cytotoxic-type classically activated microglia in the peri-contusional regions after TBI

To identify the cell types expressing gp91phox in the peri-contusional area, cells were co-labelled with antibodies raised against gp91phox and markers of microglial (CD11b), astroglial (GFAP), and neuronal (NeuN) cells (Fig 2B). The immunoreactivity for gp91phox was mainly co-localized to microglia that had amoeboid-like morphological features with round cell body and short processes, suggesting cytotoxic-type classical activation. Immunoreactive staining for gp91phox was also co-localized to a few astrocytes and neurons.

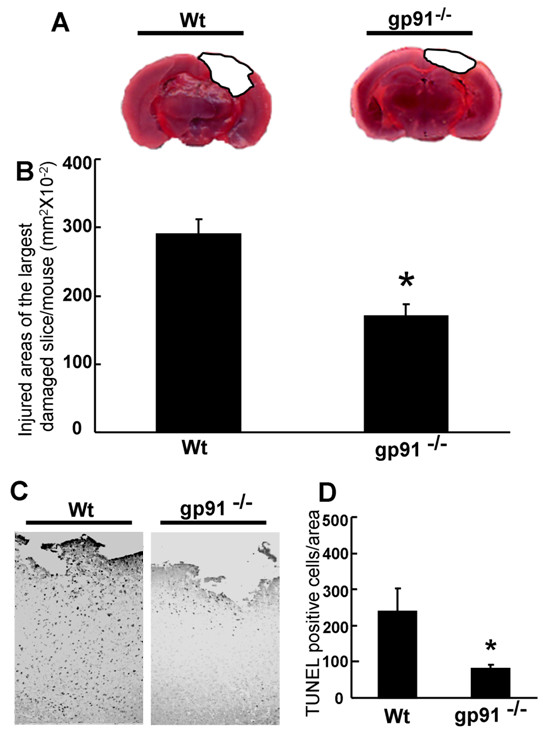

Gp91phox inhibition reduces the severity of TBI in vivo

TTC staining was used to evaluate the role of gp91phox on the severity of TBI in gp91phox-/- and Wt mice (Fig 3A, B). Images of the TTC-stained anterior surface of coronal sections demonstrated that the injured brain area in gp91phox-/- mice was significantly smaller (P < 0.01) than that of the Wt mice (Fig. 3B). We verified the prevention of the cortical injury with TUNEL staining, which was used to identify apoptotic-like cell death at 48 hours after TBI (Fig 3C, D). The number of TUNEL-positive cells of gp91phox-/- mice was significantly less (p < 0.05) compared with Wt mice (Fig 3D).

Figure 3.

Brain damage and cell death after traumatic brain injury in wild type (Wt) mice and gp91phox-/- mice. (A) 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC)-stained coronal brain sections from Wt mice (left) and gp91phox-/- mice (right) 2 days after TBI. (B) The contusion area in gp91phox-/- mice (170.5 ± 71.5 mm2 × 10-2, n = 20) was significantly smaller than that in the Wt group (290.7 ± 94.0 mm2 × 10-2, n = 10, *p < 0.01, t test). (C) Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL)-staining in peri-contusional area of wild type (left) and gp91phox-/- (right) mice 48 hours after TBI. TUNEL-positive cells numbers in the gp91phox-/- mice (117 ± 69.3 cells/area, n = 6) were significantly smaller than those in the Wt group (252 ± 128.9 cells/area, n = 6, *p < 0.05, t test) (D). All values represent the mean ± SE.

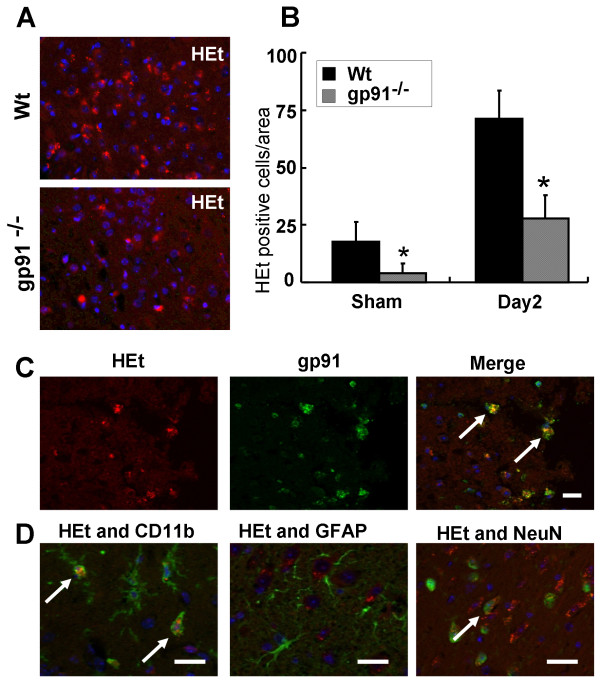

Gp91phox gene deletion reduces superoxide radical (O2-) production after TBI

High intensity fluorescence staining by the oxidation product Et was observed, indicating high levels of O2- production. The peri-contusional area of Wt mice accounted for much of the Et signal after TBI (Fig 4A). Et fluorescence was lower in gp91phox-/- mice (Fig 4A) compared to Wt mice (p < 0.05) (Fig 4B). The Et fluorescence was associated with p91phox-positive cells (Fig. 4C), and CD11b-positive microglial cells (Fig. 4D). Some Et fluorescence was slightly detected in a few neurons (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that O2- is mainly produced by microglia expressing gp91phox.

Figure 4.

The roles of gp91phox in superoxide radical production after traumatic brain injury). (A) Superoxide radical production (hydroethidium [HEt]-positive cells: shown in red) in the peri-contusional area of wild type (upper) and gp91phox-/- (lower) mice 2 days after TBI. (B) TBI-induced superoxide radical production (HEt-positive cells) in the peri-contusional area was significantly attenuated by gp91phox deficiency in sham-operated mice, and 2 days after TBI (*p < 0.05, t test). All values represent mean ± SE. (C, D) Co-localization of HEt-positivity with cell markers in the peri-contusional region. Cell identification was carried out using antibodies for gp91phox (C), CD11b (D, left), GFAP (D, middle), and Neu N (D, right) (shown in green). HEt-positive cells were co-localized with gp91phox-positive cells (C, right, arrows) and microglia-like cells (D, left, arrows). Although HEt-positive cells were also slightly co-localized with neurons (D, right, arrows), immunoreactivity was lower than for gp91phox-positive cells and microglia-like cells. Cells were counter-stained with DAPI to show nuclei (blue). Scale bars = 20 μm (C, D).

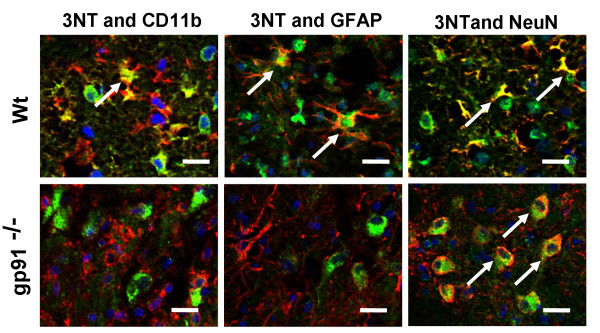

Gp91phox gene deletion reduces 3-NT generation after TBI in vivo

Peroxynitrite (ONOO-) is an oxidant and nitrating agent and is synthesized by the reaction between O2- and nitric oxide (NO). ONOO- can damage a wide array of cellular molecules, including DNA and proteins. 3-NT is an oxidized metabolite of ONOO- in vivo. We performed multiple-immunostaining for 3-NT and cell marker antibodies in the peri-contusional area at 48 hours. Immunoreactivity for 3-NT in Wt mice clearly co-localized with microglia, astrocytes, and degenerated neurons (Fig 5; upper panel). In gp91phox-/- mice, however, 3-NT immunoreactions were dramatically suppressed in the microglial and astroglial cells (Fig 5). While 3-NT immunoreactivity was observed in gp91phox-/- mouse neurons, the integrity of these cells was preserved (Fig 5). Taken together these findings suggest that production of O2- and ONOO- by gp91phox may influence the severity of TBI.

Figure 5.

Production and cell identification of peroxynitrite (ONOO-) in wild type (Wt) (upper) and gp91phox-/- (lower) mice 48 hours after TBI. ONOO- in Wt mice was produced in microglia-like cells (left, arrows), astrocytes (middle, arrows), and degenerated neurons (right, arrows). In gp91phox-/- mice, ONOO- production was strongly suppressed. In neurons, only weak production of ONOO- was observed, but degeneration of neurons was not seen (right, arrows). Scale bars = 20 μm.

Classically activated BV-2 increased gp91phox and p22phox

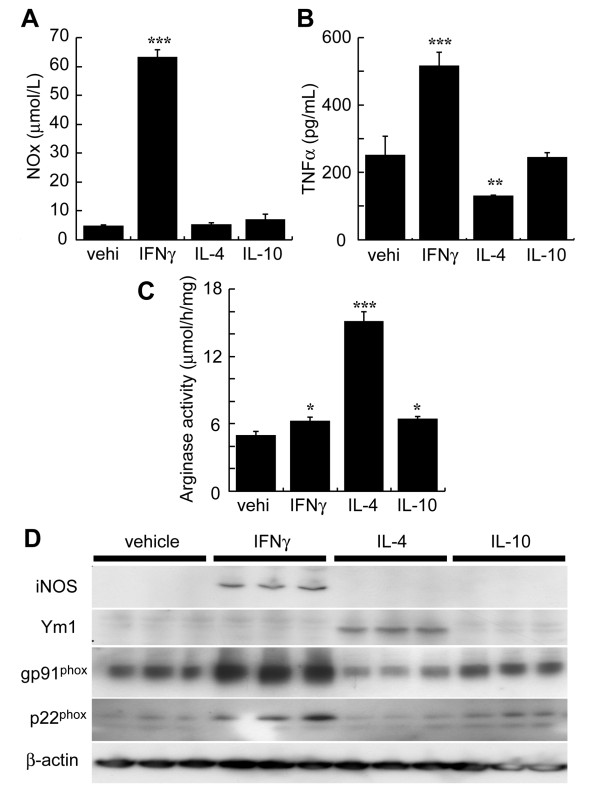

From the results presented in Fig. 2 we suggested that gp91phox co-localized with classical activated microglia. We then tried to identify the microglia that expressed gp91phox by using the mouse microglial cell line BV-2 and by activating these cells with IFNγ, IL-4, or IL-10. As shown in Fig 6, the media from the BV-2 cells showed significantly increased total NO after exposure to IFNγ, but not to IL-4 or IL-10 at 24 hours. The IFNγ-exposed BV-2 cells had significantly increased TNFα in their media and expressed iNOS as well. All of these factors indicate that the BV-2 cells were activated according to the classically activated phenotype [20]. On the other hand, the IL-4-exposed BV-2 cells showed increased arginase activity and levels of Ym-1, indicating an alternatively activated phenotype [20]. IL-10-exposed BV-2 cells did not show any changes in levels of these factors. Immunoblotting experiments showed that gp91phox levels increased in the IFNγ-exposed BV-2. Moreover, immunoblotting for a different NADPH oxidase subunit, p22phox, mirrored that of gp91phox, suggesting that not only gp91phox but also NADPH oxidase expression was induced in the classically activated microglia.

Figure 6.

Expression of gp91phox and p22phox in IFNγ-exposed classically activated mouse microglial BV-2 cells. BV-2 cells were exposed to vehicle (vehi), IFNγ, IL-4, or IL-10. The levels of microglial phenotype markers (NOx, TNFα, arginase activity, iNOS, and Ym1), gp91phox, and p22phox were evaluated in medium or cell homogenates 24 hours later. Production of (A) NOx and (B) TNFα were determined in the media. (C) Expression of iNOS, Ym1, gp91phox, and p22phox was determined by immunoblotting with reduced samples. ß-Actin levels were used as an internal control. IFNγ-exposed BV-2 cells had increased NOx, TNFα, and iNOS levels, all of which are classical activating markers of the microglial phenotype. In contrast, IL-4-exposed BV-2 cells had increased arginase activity and Ym1 levels, which are alternative markers of activation. Gp91phox and p22phox levels were increased only in IFNγ-exposed BV-2 cells, suggesting induction by classically activated microglial cells.

Discussions

We demonstrate here that gp91phox is increased in the ipsilateral hemisphere after TBI and specifically in amoeboid-shaped microglial cells. Mice that are gene-deficient for gp91phox exhibit reduced primary cortical damage, as evidenced by reduced areas of contusion, and reduced secondary damage as detected by TUNEL staining. Moreover, we have shown that the gene-deficient mice have lower levels of ROS at the injury site and widespread oxidative damage after TBI. Finally, we demonstrate in a BV-2 microglial cell line that gp91phox and/or NADPH oxidase are increased in classically activated microglial cells which are activated by IFNγ.

Gp91phox is expressed constitutively in neurons but not in glial cells, and O2- production might play a role in neuronal homeostasis [22]. However, in neuropathological conditions including neurodegenerative diseases and stroke, the gp91phox-containing NADPH oxidase has been observed in glial cells, neurons, fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells, and seems to be involved in ROS formation [22-29]. Microglial cell gp91phox appears to be involved in the induction of neuronal damage in Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and ischemic stroke [9,14,30,31]. In the present study, we demonstrated that gp91phox is mainly expressed in microglia, and at lower levels in neurons and astrocytes. These microglia exhibit features of being classically activated. We then demonstrated that the microglial phenotypes expressed both gp91phox and p22phox, which probably reflects the induction of NADPH oxidase in the BV-2 mouse microglial cell line that we used. Our results reveal that NADPH oxidase is induced in INFγ-stimulated, classically activated microglial cells characterized by increased NO, iNOS, and TNFα.

In gp91phox-/- mice, in situ generation of O2-and an ONOO- metabolite, 3-NT, were suppressed in microglia after TBI. ONOO- produced by O2- and NO after TBI [32] induces oxidative damage, secondary brain damage and neuroinflammation after TBI [5,33]. We have verified that TUNEL-positive apoptotic-like cells in the peri-contusional area and contusion area are suppressed in gp91phox-/- mice. These results suggest that gp91phox in classically activated microglia-like cells has a harmful role in primary and secondary brain damage after TBI.

The question of whether microglial cells play harmful or beneficial roles in CNS injures has been widely debated and reviewed over several decades [34-36]. The roles of activated microglia in neuroinflammation are thought to be complex. Classical activation is induced by IFNγ and is related to the production of proinflammatory mediators in the innate immune response. Another form of activation, called "alternative activation," is induced by IL-4 and IL-13 and, compared to classical activation, does not result in high levels of expression of proinflammatory mediators such as cytokines and NO. The roles of alternatively activated microglia during inflammatory process are thought to involve tissue repair, the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, fibrosis, and extracellular matrix reconstruction. Recently, Ohtaki et al. reported that the injection of human mesenchymal stromal cells protects against ischemic brain injury by modulating inflammatory and immune responses through the alternative activation of microglia and/or macrophages [37]. These studies and our data suggest that controlling microglial activation and understanding its mechanism and functional significance following TBI may open exciting new therapeutic avenues.

The suppression of free radical generation and the scavenging of free radicals after brain damage are important therapies. Animal experiments have supported the notion that free radical scavengers and antioxidants dramatically reduce TBI [1,6,38]. Excessive O2- may produce destructive hydroxyl radicals (OH-) and alkoxyl radicals (OR-) by the iron-catalyzed Haber-Weiss reaction. The brain is especially prone to radical damage because it is highly enriched in easily peroxidizable unsaturated fatty acid side chains and iron. Many studies investigating ischemic injury suggest that inhibition of NADPH oxidase or gp91 phox is an important therapeutic target for neuroprotection [39,40]. Some recent studies have demonstrated that expression of gp91phox increases in brain after intracerebral hemorrhage, resulting in enhanced lipid peroxidation [24,41]. These studies also reported that hemorrhage volume, brain edema, and neurological function are reduced in gp91phox-/- mice, while Lo et al. reported that neurological outcomes are improved in gp91phox-/- mice [42]. On the other hand, Liu et al. reported that there are no significant differences in mortality rate, brain water content and intensity of oxidative stress between gp91phox-/- and wild type mice in a mouse model of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) [43]. In the present study, we have shown that, in gp91phox-/- mice, gp91phox expressed in classically-activated microglial-like cells plays a key role in O2- production after TBI, and that gp91phox-derived O2- is a key signal for contusion and cell death after TBI. Our findings indicate that gp91phox inhibition and control of microglial classically-activation might provide a new therapeutic option by suppressing ROS generation after TBI. However, the indirect influence with TBI by which ROS production by other NOX families and immune cells such as endothelial cell or leukocytes is currently unclear and will be an important question for future TBI studies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have shown that gp91phox is expressed in classical activated microglial-like cells mainly in the peri-contusional area after TBI. An important generator of O2- is gp91phox during the acute phase of TBI. As ROS derived from gp91phox play an important role in primary and secondary brain damage after TBI, modulation of gp91phox in classically activated microglia and gp91phox-derived ROS may provide a new therapeutic strategy in combating post-traumatic brain injury.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KD performed the majority of experiments and data analysis, and wrote the initial version of the manuscript. HO was involved in evaluation of microglia using BV-2 cell. TN, SY, DS and KM were substantial contributions to western blotting assay and immunohistochemistry. ST provided gp91 knockout mice. KS, SS and TA supervised all experimental procedures. All of the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscripts.

Contributor Information

Kenji Dohi, Email: kdop@med.showa-u.ac.jp.

Hirokazu Ohtaki, Email: taki@med.showa-u.ac.jp.

Tomoya Nakamachi, Email: nakamachi@med.showa-u.ac.jp.

Sachiko Yofu, Email: syofu@hotmail.com.

Kazue Satoh, Email: kazue-sth@med.showa-u.ac.jp.

Kazuyuki Miyamoto, Email: k-miyamoto@med.showa-u.ac.jp.

Dandan Song, Email: dandansong@med.showa-u.ac.jp.

Shohko Tsunawaki, Email: tsunawaki@nch.go.jp.

Seiji Shioda, Email: shioda@med.showa-u.ac.jp.

Tohru Aruga, Email: aruga@leoc-j.com.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Mary C. Dinauer for the supply the animals. The project was supported by a Showa University Grant-in-Aid for Innovative Collaborative Research Projects, by a Special Research Grant-in-Aid for the development of Characteristic education, and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (No. 20592128, 2008) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (KD). This work was also supported in part by Research on Health Sciences focusing on Drug Innovation from The Japan Health Sciences Foundation (SS).

References

- Dohi K, Satoh K, Nakamachi T, Yofu S, Hiratsuka K, Nakamura S, Ohtaki H, Yoshikawa T, Shioda S, Aruga T. Does edaravone (MCI- 186) act as an antioxidant and a neuroprotector in experimental traumatic brain injury? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:281–287. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.9.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewen A, Matz P, Chan PH. Free radical pathways in CNS injury. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17:871–890. doi: 10.1089/neu.2000.17.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratico D, Reiss P, Tang LX, Sung S, Rokach J, McIntosh TK. Local and systemic increase in lipid peroxidation after moderate experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurochem. 2002;80:894–898. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyurin VA, Tyurina YY, Borisenko GG, Sokolova TV, Ritov VB, Quinn PJ, Rose M, Kochanek P, Graham SH, Kagan VE. Oxidative stress following traumatic brain injury in rats: quantitation of biomarkers and detection of free radical intermediates. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2178–2189. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng-Bryant Y, Singh IN, Carrico KM, Hall ED. Neuroprotective effects of tempol, a catalytic scavenger of peroxynitrite-derived free radicals, in a mouse traumatic brain injury model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1114–1126. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewen A, Skoglosa Y, Clausen F, Marklund N, Chan PH, Lindholm D, Hillered L. Paradoxical increase in neuronal DNA fragmentation after neuroprotective free radical scavenger treatment in experimental traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:344–350. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200104000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd RA, Carney JM. Free radical damage to protein and DNA: mechanisms involved and relevant observations on brain undergoing oxidative stress. Ann Neurol. 1992;32(Suppl):S22–27. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramov AY, Duchen MR. The role of an astrocytic NADPH oxidase in the neurotoxicity of amyloid beta peptides. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:2309–2314. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infanger DW, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. NADPH oxidases of the brain: distribution, regulation, and function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1583–1596. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazama K, Anrather J, Zhou P, Girouard H, Frys K, Milner TA, Iadecola C. Angiotensin II impairs neurovascular coupling in neocortex through NADPH oxidase-derived radicals. Circ Res. 2004;95:1019–1026. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000148637.85595.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard K, Lardy B, Krause KH. NOX family NADPH oxidases: not just in mammals. Biochimie. 2007;89:1107–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Canadien V, Lam GY, Steinberg BE, Dinauer MC, Magalhaes MA, Glogauer M, Grinstein S, Brumell JH. Activation of antibacterial autophagy by NADPH oxidases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Huang J, Canadien V, Lam GY, Steinberg BE, Dinauer MC, Magalhaes MA, Glogauer M, Grinstein S, Brumell JH. Activation of antibacterial autophagy by NADPH oxidases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zekry D, Epperson TK, Krause KH. A role for NOX NADPH oxidases in Alzheimer's disease and other types of dementia? IUBMB Life. 2003;55:307–313. doi: 10.1080/1521654031000153049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinauer MC, Deck MB, Unanue ER. Mice lacking reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activity show increased susceptibility to early infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 1997;158:5581–5583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa K, Dohi K, Yofu S, Mihara Y, Nakamachi T, Ohtaki H, Shioda S, Aruga T. Expression and Localization of Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase-Activating Polypeptide-Specific Receptor (PAC1R)..After Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice. Open Crit Care Med J. 2008;1:33–38. doi: 10.2174/1874828700801010033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henn A, Lund S, Hedtjarn M, Schrattenholz A, Porzgen P, Leist M. The suitability of BV2 cells as alternative model system for primary microglia cultures or for animal experiments examining brain inflammation. Altex. 2009;26:83–94. doi: 10.14573/altex.2009.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida LS, Saruta F, Yoshikawa K, Tatsuzawa O, Tsunawaki S. Mutation at histidine 338 of gp91(phox) depletes FAD and affects expression of cytochrome b558 of the human NADPH oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27879–27886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindokas VP, Jordan J, Lee CC, Miller RJ. Superoxide production in rat hippocampal neurons: selective imaging with hydroethidine. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1324–1336. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01324.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S. rnative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corraliza I, Campo M, Soler G, Modolell M. Determination of arginase activity in macrophages: a micromethod. J Immunol Methods. 1994;174:231–235. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano F, Kolluri NS, Wientjes FB, Card JP, Klann E. NADPH oxidase immunoreactivity in the mouse brain. Brain Res. 2003;988:193–198. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(03)03364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimohama S, Tanino H, Kawakami N, Okamura N, Kodama H, Yamaguchi T, Hayakawa T, Nunomura A, Chiba S, Perry G, Smith MA, Fujimoto S. Activation of NADPH oxidase in Alzheimer's disease brains. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:5–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman KA, Miller AA, De Silva TM, Crack PJ, Drummond GR, Sobey CG. Reduction of cerebral infarct volume by apocynin requires pretreatment and is absent in Nox2-deficient mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:680–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Liu J, Zhou C, Ostanin D, Grisham MB, Neil Granger D, Zhang JH. Role of NADPH oxidase in the brain injury of intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1342–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharam V, Kaul S, Song C, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Pharmacological inhibition of neuronal NADPH oxidase protects against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+)-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in mesencephalic dopaminergic neuronal cells. Neurotoxicology. 2007;28:988–997. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlach A, Brandes RP, Nguyen K, Amidi M, Dehghani F, Busse R. A gp91phox containing NADPH oxidase selectively expressed in endothelial cells is a major source of oxygen radical generation in the arterial wall. Circ Res. 2000;87:26–32. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilburger EW, Conte EJ, McGee DW, Tammariello SP. Localization of NADPH oxidase subunits in neonatal sympathetic neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2005;377:16–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AA, Dusting GJ, Roulston CL, Sobey CG. NADPH-oxidase activity is elevated in penumbral and non-ischemic cerebral arteries following stroke. Brain Res. 2006;1111:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SP, Cairns B, Rae J, Errett-Baroncini C, Hongo JA, Erickson RW, Curnutte JT. Induction of gp91-phox, a component of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase, in microglial cells during central nervous system inflammation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:374–384. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200104000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin B, Cartier L, Dubois-Dauphin M, Li B, Serrander L, Krause KH. A key role for the microglial NADPH oxidase in APP-dependent killing of neurons. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:1577–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian RH, DeWitt DS, Kent TA. In vivo detection of superoxide anion production by the brain using a cytochrome c electrode. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1995;15:242–247. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1995.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh IN, Sullivan PG, Deng Y, Mbye LH, Hall ED. Time course of post-traumatic mitochondrial oxidative damage and dysfunction in a mouse model of focal traumatic brain injury: implications for neuroprotective therapy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1407–1418. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch UK, Kettenmann H. Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1387–1394. doi: 10.1038/nn1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit WJ. Microglial senescence: does the brain's immune system have an expiration date? Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:506–510. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtaki H, Ylostalo JH, Foraker JE, Robinson AP, Reger RL, Shioda S, Prockop DJ. Stem/progenitor cells from bone marrow decrease neuronal death in global ischemia by modulation of inflammatory/immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14638–14643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803670105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh PW, Belayev L, Zhao W, Clemens JA, Panetta JA, Busto R, Ginsberg MD. Neuroprotection by LY341122, a novel inhibitor of lipid peroxidation, against focal ischemic brain damage in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;389:79–88. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(99)00768-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambeth JD, Krause KH, Clark RA. NOX enzymes as novel targets for drug development. Semin Immunopathol. 2008;30:339–363. doi: 10.1007/s00281-008-0123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahles T, Luedike P, Endres M, Galla HJ, Steinmetz H, Busse R, Neumann-Haefelin T, Brandes RP. NADPH oxidase plays a central role in blood-brain barrier damage in experimental stroke. Stroke. 2007;38:3000–3006. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.489765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Liu J, Zhou C, Ostanin D, Grisham MB, Granger DN, Zhang JH. Role of NADPH oxidase in the brain injury of intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1342–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo W, Bravo T, Jadhav V, Titova E, Zhang JH, Tang J. NADPH oxidase inhibition improves neurological outcomes in surgically-induced brain injury. Neurosci Lett. 2007;414:228–232. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Tang J, Ostrowski RP, Titova E, Monroe C, Chen W, Lo W, Martin R, Zhang JH. Oxidative stress after subarachnoid hemorrhage in gp91phox knockout mice. Can J Neuro sci. 2007;34:356–361. doi: 10.1017/s031716710000682x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]