Abstract

We report the work of developing a hand-held (or miniaturized), low-cost, stand-alone, real-time-operation, narrow bandwidth multispectral imaging device for the detection of early stage pressure ulcers.

Keywords: ulcer, multispectral imaging, single sensor, narrow bandwith

Introduction

Early stage pressure ulcers and other subcutaneous lesions are nearly invisible in clinical settings, particularly so for dark pigmented skin. An earlier study indicated multispectral images can enhance the contrast between damaged and normal skin. Although multispectral imaging has matured into a technology with applications in many fields, clinical practitioners in the fields of health care and rehabilitation have generally stayed away from it due to extremely high cost and lack of portability. Also, other multispectral imaging technologies require either multiple exposures or extensive postprocessing.

In has long been desirable to reduce the size and weight of multispectral imaging sensors to facilitate their practical applications.1 The effort of developing a hand-held, low-cost, stand-alone, multispectral imaging tool to satisfy the need of clinically detecting early stage pressure ulcers stimulates a new way in architecting the device.2 Instead of using bulky and expensive traditional optical filters, e.g., filter wheels, a generalized Lyot filter, and electrically tunable filter, multiple-band pass filters,3 or the methods of dispersing light, e.g., optic-acoustic crystals,4 we report a custom-designed filter mosaic that has been successfully fabricated using lithography and vacuum multilayer film technologies.

Method

Sprigle, Zhang, and Duckworth5 suggest that three or four wavelengths are sufficient for the detection of early stage pressure ulcers. The filter mosaic allows light of specific wavelengths centered at λ1=540, λ2=577, λ3=650, and λ4=970 nm to pass through; so, the resulting imager can be best tuned to the characteristic chromospheres existing in pressure ulcers. 540 and 577 nm correspond to the hemoglobin absorption peaks, 650 nm gives us a melanin or background image, and 970 targets the water peak plus it gives deep penetration. A bandwidth of 30 nm is used for the detection of pressure ulcers, although the manufacturing processes can achieve a narrower bandwidth of 5 nm if needed.

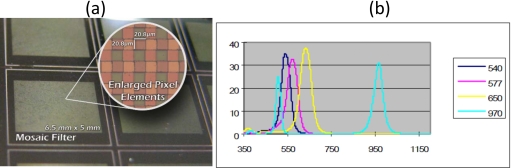

The filter mosaic can be deposited on regular optical glass as a substrate or directly on a complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) or charge-coupled device (CCD) imaging sensor. Figure 1a shows the first prototype version of the filter. Subsequent improvements to the fabrication process have reduced the spacing (gap and border) between individual filter cells to 1 to 2 μm. The area of a single wavelength cell is 20.8×20.8 μm and represents a compromise between spatial resolution and initial fabricating cost, although a better spatial resolution of 5×5 μm can be achieved. For pressure ulcer detection, this spatial resolution is acceptable, as the target is often very close to the imaging sensor, often within 1 m in distance. Figure 1b shows the measured response of the filter mosaic to light.

Figure 1.

(a) A section of the prototype mosaic filter for the set of wavelengths λ=540, 577, 650, and 970 nm. The image shown was taken from a CCD microscope. (b) Transmittance of the four wavelengths through the filter array. (Color online only.)

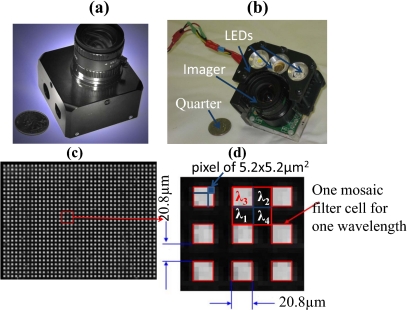

Integration procedures have been established to laminate the filter of a certain cell size with commercial CCD and CMOS imaging sensors of different pixel sizes. Figure 2a shows a multispectral imager obtained by integrating the prototyped filter mosaic with a CMOS imager MT9M001C12STM with a pixel size 5.2×5.2 μm produced by Aptina Imaging (Corvalis, Oregon). A United States currency quarter is placed beside the imager to indicate its compact size. The filter mosaic is also integrated with CCD imaging sensors (e.g., ICx205AL, pixel size 4.65×4.65 μm, produced by Sony, result not shown). For better control of the illumination that targets pressure ulcers, the multispectral imager is further integrated with three LED light sources: one warm light, one green light, and one infrared light [see Fig. 2b]. Figure 2c provides one raw image obtained with the resulting compact imaging sensor of a flat sheet illuminated by green light centered at 650 nm.

Figure 2.

(a) An erythema imager is created by laminating a filter mosaic with a Mightex USB2 camera’s monochromic CMOS sensor (MT9M001C12STM), and (b) integrating the erythema imager with three LED lighting sources. (c) A resulting raw image of a flat sheet illuminated by a green light of wavelength centered at 650 nm. (d) An enlarged version of a few filter mosaic cells.

Figure 2d gives an enlarged version of a few mosaic filter cells, from which one can see that, as expected, only cells of size 20.8×20.8 μm that correspond to the spectral component of wavelength 650 nm are lit up, leaving cells of other spectral components (λ1=540, λ2=577, and λ4=970 nm) at rather low intensity. This indicates spatial resolution is inversely related to the number of spectral components, i.e., reduced spectral resolution. Miao and Qi6 provide an interpolation technique to estimate the response to one spectral component (e.g., λ3) at locations that are occupied by other spectral components (e.g., λ[1,2,4]) to recover the lost spatial resolution.

Results

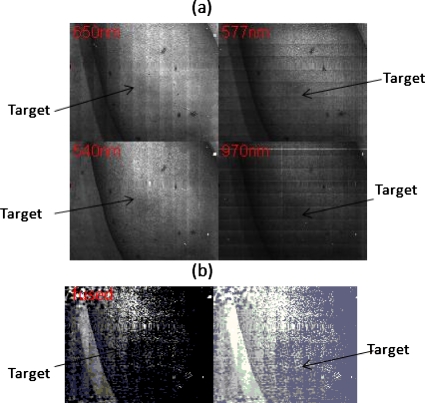

The prototyped multispectral imager detects early stage pressure ulcers. An erythema is induced by a pressure ball on dark pigmented skin where it is barely visible to the naked eye (not shown). With a single shot, the integrated multispectral imager produces in real time four images corresponding to wavelengths 540, 577, 650, and 970 nm, where the erythema becomes visible, although not very clearly [Fig. 3a]. The real time-fused image is shown in Fig. 3b, where the erythema is more apparent than in the single multispectral image. The simple fusion algorithm used to enhance the contrast between erythema and its background is:

| (1) |

The positive signs for channels 540 and 577 nm are because the peak absorption of known characteristic chromophores of pressure ulcers including oxy-and deoxyhemoglobin are at 540 and 577 nm. The 650-nm channel is subtracted as it corresponds to melanin content that is constant across erythematic and nonerythematic skin. The spectral component at 977 nm is not used, as the original imaging sensor MT9M001C12STM has rather low sensitivity in this region. Image processing work with other fusion algorithms and for curvature correction is ongoing.

Figure 3.

Real-time acquired images of an erythema on a dark pigmented arm. The four images correspond to four different wavelengths λ[1,2,3,4]. (b) Left side shows the fused view of the erythema. The fusion algorithm is given by Eq. 1. Right shows the same as the left, but with a histogram equalization procedure being applied.

Conclusion

The reported custom-designed filter mosaic is successfully fabricated and integrated with commercial imaging sensors. The resulting multispectral imager permits multiple images centered at different wavelengths to be acquired in a single exposure, thereby providing overwhelming operational convenience. The real-time production of multispectral images allows instant detection of pressure ulcers. Its capability for real-time detection, miniature size, fully electronic construction with no mechanical components, and immunity from motion-induced distortion facilitates its clinical application in healthcare and rehabilitation fields.

The primary benefits of the core technology reported here, i.e., the new filter mosaic, are cost and size. It has the potential to replace many similarly constructed instruments that are widely used in traditional industries, including inspection of agricultural products, food manufacturing, military target detection, etc. It can also be used to build innovative tools or to enhance the capacity of existing ones in modern scientific research.

Future Work

Our ongoing work on fine correction to address any misalignment between the filter mosaic and underlying camera pixels is promising. With slight modification, it can also be used to provide multispectral images with finer spatial resolution by the addition of linear interpolation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Barrie J. D., Aitchison K. A., Rossano G. S., and Abraham M. H., “Patterning of multilayer dielectric optical coatings for multispectral CCDs,” Thin Solid Films 270(1–2), 6–9 (1995). 10.1016/0040-6090(95)06888-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L., Sprigle L. S., Duckworth M., Yi D., Caspall J., Wang J., and Zhao F., “Handheld erythema and bruise detector,” Proc. SPIE 6915, 69153K (2008). 10.1117/12.770718 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Themelis G., Yoo J. S., and Ntziachristos V., “Multispectral imaging using multiple-band pass filters,” Opt. Lett. 33(9), 1023 (2008). 10.1364/OL.33.001023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila J., Calpe J., Pla F., Gomez L., Connell J., Marchant J., Calleja J., Mulqueen M., Munoz J., and Klaren A., “SmartSpectra: applying multispectral imaging to industrial environments,” Real-Time Imag. 11, 85–98 (2005). 10.1016/j.rti.2005.04.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sprigle S., Zhang L., and Duckworth M., “Detection of skin erythema in darkly pigmented skin using multispectral images,” Adv. Skin Wound Care 22(4), 172–179 (2009). 10.1097/01.ASW.0000305465.17553.1c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao L. and Qi H. R., “The design and evaluation of a generic method for generating mosaicked multispectral filter arrays,” IEEE Trans. Image Process. 15(9), 2780–2791 (2006). 10.1109/TIP.2006.877315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]