Abstract

Analyses of the refined X-ray crystallographic structures of Photosystem II (PSII) at 2.9 – 3.5 Å have revealed the presence of possible channels for the removal of protons from the catalytic Mn4Ca cluster during the water-splitting reaction. As an initial attempt to verify these channels experimentally, the presence of a network of hydrogen bonds near the Mn4Ca cluster was probed with FTIR difference spectroscopy in a spectral region sensitive to the protonation states of carboxylate residues, and in particular, with a negative band at 1747 cm−1 that is often observed in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum of PSII from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. On the basis of its 4 cm−1 downshift in D2O, this band was assigned to the carbonyl stretching vibration (C=O) of a protonated carboxylate group whose pKA decreases during the S1 to S2 transition. The positive charge that forms on the Mn4Ca cluster during the S1 to S2 transition presumably causes structural perturbations that are transmitted to this carboxylate group via electrostatic interactions and/or an extended network of hydrogen bonds. In an attempt to identify the carboxylate group that gives rise to this band, the FTIR difference spectra of PSII core complexes from the mutants D1-Asp61Ala, D1-Glu65Ala, D1-Glu329Gln, and D2-Glu312Ala were examined. In the X-ray crystallographic models, these are the closest carboxylate residues to the Mn4Ca cluster that do not ligate Mn or Ca and all are highly conserved. The 1747 cm−1 band is present in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum of D1-Asp61Ala, but is absent from the corresponding spectra of D1-Glu65Ala, D2-Glu312Ala, and D1-Glu329Gln. The band is also sharply diminished in wild-type when samples are maintained at a relative humidity of 85% or less. It is proposed that D1-Glu65, D2-Glu312, and D1-Glu329 participate in a common network of hydrogen bonds that includes water molecules and the carboxylate group that gives rise to the 1747 cm−1 band. It is further proposed that the mutation of any of these three residues, or partial dehydration caused by maintaining samples at a relative humidity of 85% or less, disrupts the network sufficiently that the structural perturbations associated with S1 to S2 transition are no longer transmitted to the carboxylate group that gives rise to the 1747 cm−1 band. Because D1-Glu329 is located approximately 20 Å from D1-Glu65 and D2-Glu312, the postulated network of hydrogen bonds must extend for at least 20 Å across the lumenal face of the Mn4Ca cluster. The D1-Asp61Ala, D1-Glu65Ala, and D2-Glu312Ala mutations also appear to substantially decrease the fraction of PSII reaction centers that undergo the S3 to S0 transition in response to a saturating flash. This behavior is consistent with D1-Asp61, D1-Glu65, and D2-Glu312 participating in a dominant proton egress channel that link the Mn4Ca cluster with the thylakoid lumen.

The light-driven oxidation of water in Photosystem II (PSII)1 produces nearly all of the O2 on Earth and drives the production of nearly all of its biomass. Photosystem II is an integral membrane protein complex that is located in the thylakoid membranes of plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. It is a homodimer in vivo, having a total molecular weight of over 700 kDa. Each monomer consists of at least 20 different subunits and contains over 60 organic and inorganic cofactors including 35 Chl a and 12 carotenoid molecules. Each monomer’s primary subunits include the membrane spanning polypeptides CP47 (56 kDa), CP43 (52 kDa), D2 (39 kDa), and D1 (38 kDa), and the extrinsic polypeptide PsbO (26.8 kDa). The D1 and D2 polypeptides are homologous and together form a heterodimer at the core of each monomer. Within each monomer, the CP47 and CP43 polypeptides are located on either side of the D1/D2 heterodimer and serve to transfer excitation energy from the peripherally-located antenna complex to the D1/D2 heterodimer, and specifically to the photochemically active Chl a multimer known as P680 (1–6).

The O2-evolving catalytic site consists of a pentanuclear metal cluster containing four Mn ions and one Ca ion. The Mn4Ca cluster accumulates oxidizing equivalents in response to photochemical events within PSII and then catalyzes the oxidation of two molecules of water, releasing one molecule of O2 as a by-product (7–11). The Mn4Ca cluster serves as the interface between single-electron photochemistry and the four-electron process of water oxidation. The photochemical events that precede water oxidation take place in the D1/D2 heterodimer. These events are initiated by the transfer of excitation energy to P680 following capture of light energy by the antenna complex. Excitation of P680 results in the formation of the charge-separated state, P680•+Pheo•−. This light-induced separation of charge is stabilized by the rapid oxidation of Pheo• − by QA, the primary plastoquinone electron acceptor, and by the rapid reduction of P680•+ by YZ, one of two redox-active tyrosine residues in PSII. The resulting YZ• radical in turn oxidizes the Mn4Ca cluster, while QA• − reduces the secondary plastoquinone, QB. Subsequent charge-separations result in further oxidation of the Mn4Ca cluster and in the two-electron reduction and protonation of QB to form plastoquinol, which subsequently exchanges into the membrane-bound plastoquinone pool. During each catalytic cycle, two molecules of plastoquinol are produced at the QB site and the Mn4Ca cluster cycles through five oxidation states termed Sn, where “n” denotes the number of oxidizing equivalents that are stored (n = 0 – 4). The S1 state predominates in dark-adapted samples. Most interpretations of Mn-XANES data have concluded that the S1 state consists of two Mn(III) and two Mn(IV) ions and that the S2 state consists of one Mn(III) and three Mn(IV) ions (11–14). The S4 state is a transient intermediate. Its formation triggers the rapid oxidation of the two substrate water molecules, the regeneration of the S0 state, and the release of O2.

Refined X-ray crystallographic structural models of PSII are available at 3.5 Å (1), 3.0 Å (2), and 2.9 Å (5) (although the 2.9 Å structural model was developed by reprocessing the data used for the 3.0 Å model). These models, plus less-complete models at somewhat lower resolutions (15, 16), provide views of the Mn4Ca cluster and its ligation environment, including 1 – 2 catalytically-essential Cl−hat are located 6 – 7 Å distant. However, there are significant differences between these views. For example, in the 2.9 and 3.0 Å structural models, most carboxylate ligands are bidentate and the α-COO− group of D1-Ala344 (the C-terminus of the D1 polypeptide) ligates the Mn4Ca cluster, whereas in the 3.5 Å structural model, most carboxylate ligands are unidentate and the α-COO− group of D1-Ala344 ligates no metal ion. One reason for these differences is that the resolutions of the diffraction data are limited. A second reason is that the Mn(III/IV) ions of the Mn4Ca cluster were undoubtedly reduced by X-ray generated radicals to their fully reduced Mn(II) oxidation states during collection of the X-ray diffraction data (17, 18). This reduction would have disrupted the cluster’s Mn-O-Mn bridging moieties and altered Mn-ligand interactions. Consequently, the structures of the Mn4Ca cluster depicted in the X-ray crystallographic models represent unknown superimpositions of native and disrupted Mn4Ca clusters, with the metal ions in the latter being retained in the vicinity of their native positions by virtue of the crystals being kept frozen at 100 K during data collection. Importantly, none of the crystallographic structural models is fully compatible with polarized EXAFS studies of single crystals of PSII that were conducted with low X-ray fluxes that minimize photoreduction of the Mn ions (19). The low radiation flux studies must be reconciled with future X-ray crystallographic studies. Nevertheless, the existing crystallographic studies agree with each other, and with the earlier mutagenesis studies (20), on the identity of most of the Mn4Ca cluster’s amino acid ligands. Furthermore, the structure of PSII outside the immediate environment of the Mn4Ca cluster should be largely unaffected by the radiation-induced reduction of the cluster’s Mn ions. Consequently, the existing crystallographic structural models are serving as valuable guides for spectroscopic studies designed to provide insight into the structure, dynamics, and mechanism of the Mn4Ca cluster throughout its catalytic cycle.

To satisfy the very severe energetic and mechanistic constraints of oxidizing water, the Mn4Ca cluster’s reactivity in each of its oxidation states is tightly controlled by its protein environment. The amino acid residues in this environment choreograph the proton and electron reactions associated with water oxidation and play important roles in the delivery of substrate water and the release of O2 and protons. In particular, these residues minimize the energetic requirements for water oxidation by coupling the requisite proton and electron extraction reactions (7, 13, 21, 22), minimize deleterious side-reactions by preventing unregulated access of water to the Mn4Ca catalyst (23), and minimize oxidative damage by promoting rapid egress of newly formed O2 (24). For example, the deprotonation of CP43-Arg357 or D1-Asp61 to the thylakoid lumen has been proposed to provide the thermodynamic driving force for oxidizing the Mn4Ca cluster in its higher oxidation states (7, 13, 21, 22, 25–28). Deprotonation is envisioned to take place via one or more proton egress pathways or “channels.” Several possible channels for water access, O2 egress, and proton egress have been identified in the current crystallographic structural models on the basis of visual examinations (1, 29–31), electrostatic calculations (32), solvent accessibility simulations (33), cavity searching algorithms (5, 34, 35), and molecular dynamics simulations of water diffusion (36). In the 2.9 Å structural model, nine discrete channels have been identified on the basis of cavity searching algorithms, including four attributed to water access or O2 egress channels and five attributed to proton egress channels (5, 35). These predicted channels are presumably dynamic in nature and presumably contain extensive networks of hydrogen bonded amino acid side chains and water molecules. Our goal is to employ FTIR difference spectroscopy to further delineate the proton egress pathways leading from the Mn4Ca cluster to the lumen and to determine if multiple pathways are active or if a single pathway dominates. Such a situation prevails in reaction centers of Rhodobacter sphaeroides, where a single proton entry point and a single proton access channel dominate proton transfer to QB (37–39).

FTIR difference spectroscopy is an extremely sensitive tool for characterizing the dynamic structural changes that occur during an enzyme’s catalytic cycle (40–44). It is particularly suited for analyzing protonation/deprotonation reactions, pKA shifts, and changes in hydrogen bonded structures in proteins. The carbonyl stretching mode [ν(C=O)] of a protonated carboxylate residue appears between 1770 and 1700 cm−1, a region where no other protein bands occur. The actual frequency of this mode depends on the number and strengths of hydrogen bonds involving this group (45–49). The O–H stretching frequency of weakly hydrogen bonded O–H groups appears between 3700 and 3500 cm−1 (50–52), the O–D stretching frequency of weakly deuteron-bonded O–D groups appears between 2600 and 2200 cm−1 (51), and the D-O-D bending region of D2O molecules appears between 1250 and 1150 cm−1 (53, 54), also in a region mostly devoid of other protein vibrational modes. This mode is also sensitive to hydrogen (deuteron) bonding and disappears upon deprotonation, making it particularly suitable for monitoring proton release reactions. Changes in the hydrogen bonding status of amino acid residues and water molecules participating in putative water access or proton egress pathways can be monitored at these easily accessible frequencies.

In PSII, numerous vibrational modes are altered in frequency as the Mn4Ca cluster is oxidized through the S state cycle, including many modes that are attributable to carboxylate residues and hydrogen-bonded water molecules (55–57). In this study, on the basis of the presence or absence of the ν(C=O) mode of a protonated carboxylate group in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum, we present evidence that the residues D1-Glu65, D1-Glu329, and D2-Glu312 participate in a hydrogen-bonded network that extends at least 20 Å across the lumenal face of the Mn4Ca cluster. This network presumably also includes D1-Asp61. The D1-D61A, D1-E65A, and D2-E312A mutations were also found to substantially decrease the fraction of PSII reaction centers that undergo the S3 to S0 transition in response to a saturating flash. Consequently, the hydrogen-bonded network that includes D1-Asp61, D1-Glu65, D2-Glu312, and D1-Glu329 may comprise part of a dominant proton egress pathway leading from the Mn4Ca cluster to the thylakoid lumen. The participation of D1-Asp61, D1-Glu65, and D2-Glu312 in such a pathway has been proposed previously (1, 5, 32–35), but the participation of D1-Glu329 in the same network is unexpected because it is located far from any proposed proton egress channel.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of Mutant and Propagation of Cultures

The D1-D61A, D1-E65A, and D1-E329Q mutations were constructed in the psbA-2 gene of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (58) and transformed into a host strain of Synechocystis that lacks all three psbA genes and contains a hexahistidine-tag (His-tag) fused to the C-terminus of CP47 (59). Single colonies were selected for ability to grow on solid media containing 5 μg/mL kanamycin monosulfate. The D2-E312A mutation was constructed in the psbD-1 gene of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (60) and transformed into a host strain of Synechocystis that lacks both psbD genes and contains a hexahistidine-tag (His-tag) fused to the C-terminus of CP47 (59). Single colonies were also selected for ability to grow on solid media containing 5 μg/mL kanamycin monosulfate. Solid media contained 5 mM glucose and 10 YM DCMU. The DCMU and antibiotic were omitted from the liquid cultures. Large-scale liquid cultures (each consisting of three 7-L cultures held in glass carboys) were propagated as described previously (61). To verify the integrity of the mutant cultures that were harvested for the purification of PSII core complexes, an aliquot of each culture was set aside and the sequence of the relevant portions of the psbA-2 or psbD-1 genes were obtained after PCR amplification of genomic DNA (58).

Purification of PSII core complexes

Oxygen-evolving PSII core complexes were purified under dim green light at 4 °C with Ni-NTA superflow affinity resin (Qiagen, Valentia, CA) as described previously (62). The purification buffer consisted of 1.2 M betaine, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 50 mM MES-NaOH (pH 6.0), 20 mM CaCl2, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM histidine, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.03% (w/v) n-dodecyl β-D-maltoside. The purified PSII core complexes were concentrated to ~ 1.0 mg of Chl/mL by ultrafiltration, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −196 °C (vapor phase nitrogen).

Preparation of FTIR Samples

All manipulations were conducted under dim green light at 4 °C. Samples (approximately 70 μg of Chl a) were exchanged into FTIR analysis buffer [40 mM sucrose, 10 mM MES-NaOH (pH 6.0), 5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM NaCl, 0.06% (w/v) n-dodecyl β-D-maltoside (63, 64)] by passage through a centrifugal gel filtration column at 27 x g (65). Concentrated samples (approx. 10 βL in volume) were mixed with 1/10 volume of fresh 100 mM potassium ferricyanide (dissolved in water), spread to a diameter of about 10 mm on a 15 mm diameter BaF2 window, then dried lightly (until tacky) under a stream of dry nitrogen gas. To maintain the humidity of the sample in the FTIR cryostat, 1 βL of a solution of glycerol in water was spotted onto the window, adjacent to the sample, but not touching it (66). For most experiments, 1 βL of 20% (v/v) glycerol was employed to maintain the samples at 99% RH. For the experiments of Figure 1A, lower relative humidities were obtained by increasing the concentration of glycerol in the 1 βL droplet [e.g., 40, 50, and 60 % (v/v) glycerol for 95, 85, and 73% RH, respectively (66)]. A second IR window with a Teflon spacer (0.5 mm thick) was placed over the first and sealed in place with silicon-free high-vacuum grease. The sample was immediately loaded into the FTIR cryostat and allowed to equilibrate to 273.0 K in darkness for 2 h. Sample concentrations and thicknesses were adjusted so that the absolute absorbance of the amide I band at 1657 cm−1 was 0.8 – 1.2. For the experiments of Figure 1B, the FTIR analysis buffer and the potassium ferricyanide and glycerol solutions were prepared with D2O (99.9% enrichment, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA). The pD of the FTIR analysis buffer prepared in D2O was adjusted with freshly-opened NaOD (99.5% enrichment, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA). The pD value was obtained by adding 0.40 to the pH meter reading (67, 68).

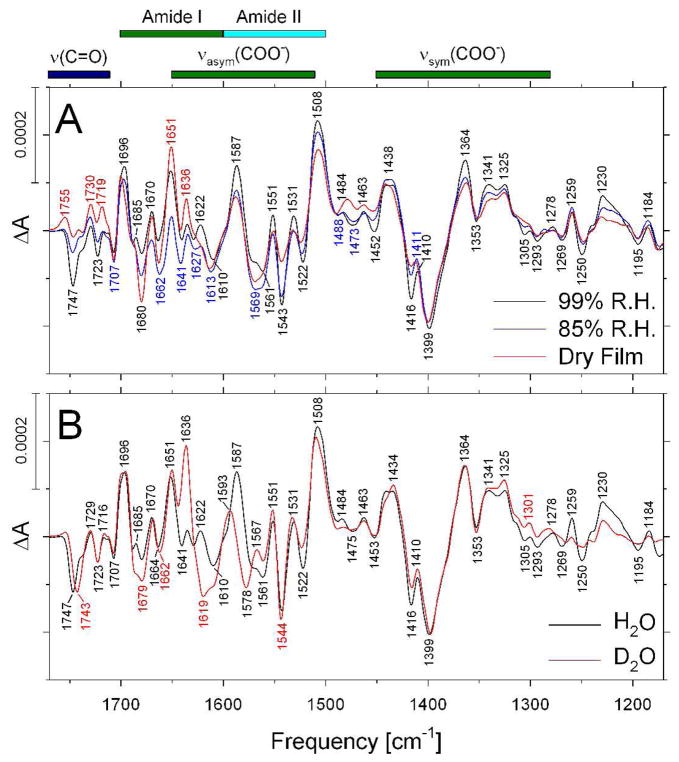

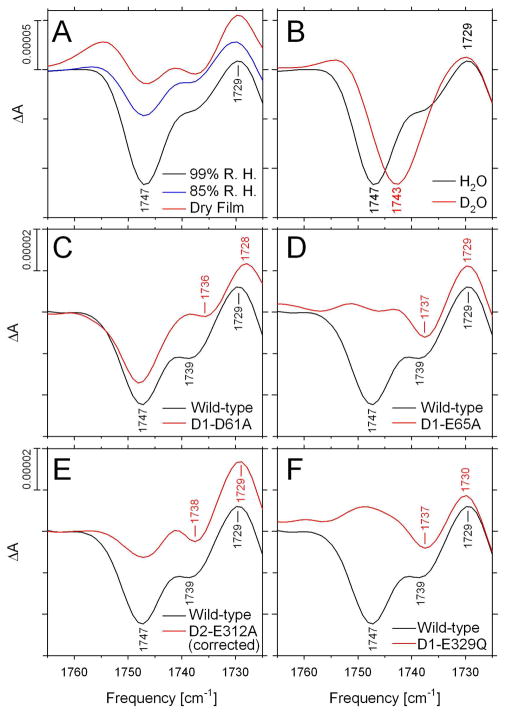

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of the mid-frequency S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectra of wild-type PSII core complexes (A) maintained at a relative humidity of 99% (black) or 85% (blue) or as a dry film in the sample cell (red) or (B) exchanged into FTIR buffer containing H2O (black) or D2O (red) and maintained at a relative humidity of 99% (in an atmosphere of H2O or D2O, respectively). In (A), the spectra have been normalized to the peak-to-peak amplitudes of the negative ferricyanide peak at 2115 cm−1 and the positive ferricyanide peak at 2038 cm−1. In (B), the spectra have been normalized to maximize overlap between 1450 and 1350 cm−1. The black, blue, and red traces in (A) represent the averages of four, seven, and four samples, respectively, and consist of 13,800, 24,200, and 13,400 scans, respectively. The black and red traces in (B) each represent the average of four samples and consist of 13,800 and 13,600 scans, respectively. The sample temperature was 273 K.

Measurement of FTIR Spectra

Mid-frequency FTIR spectra were recorded with a Bruker Equinox 55 spectrometer (Bruker Optics, Billerica, MA) at a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1 as described previously (61, 64, 65). Flash-illumination (~ 20 mJ/flash, ~ 7 ns fwhm) was provided by a frequency-doubled Q-switched Nd:YAG laser [Surelite I (Continuum, Santa Clara, CA)]. For the experiments of Figure 1, a single flash was applied after dark-adaptation. Two single beam spectra were recorded before the flash and one single-beam spectrum was recorded starting 0.33 sec after the flash (each single-beam spectrum consisted of 200 scans). The 0.33 sec delay was incorporated to allow for the oxidation of QA− by the ferricyanide. To obtain a difference spectrum, the spectrum that was recorded after the flash was divided by the spectrum that was recorded immediately before the flash and the ratio was converted to units of absorption. To estimate the background noise level, the second pre-flash spectrum was divided by the first and the ratio was also converted to units of absorption. The sample was dark-adapted for 30 min, then the measurement cycle was repeated. Each sample was subjected to a total of 16 – 18 measurement cycles. The difference spectra recorded with several samples were averaged. For the experiments of Figures 2 – 6, one pre-flash was applied after dark-adaptation and followed by 5 min of additional dark-adaptation. This treatment was employed to oxidize YD and to maximize the proportion of PSII reaction centers in the S1 state. Six successive flashes then were applied with an interval of 12.2 sec between each. Two single-beam spectra were recorded before the first flash and one single-beam spectrum was recorded starting 0.33 sec after the first and subsequent flashes (each single-beam spectrum consisted of 100 scans). To obtain difference spectra corresponding to successive S state transitions, the spectrum that was recorded after the nth flash was divided by the spectrum that was recorded immediately before the nth flash and the ratio was converted to units of absorption. To estimate the background noise level, the second pre-flash spectrum was divided by the first and the ratio was converted to units of absorption. The sample was dark-adapted for 30 min, then the entire cycle was repeated, including the pre-flash and the 5 min additional dark-adaptation period. The entire cycle was repeated 12 times for each sample and the difference spectra recorded with several samples were averaged.

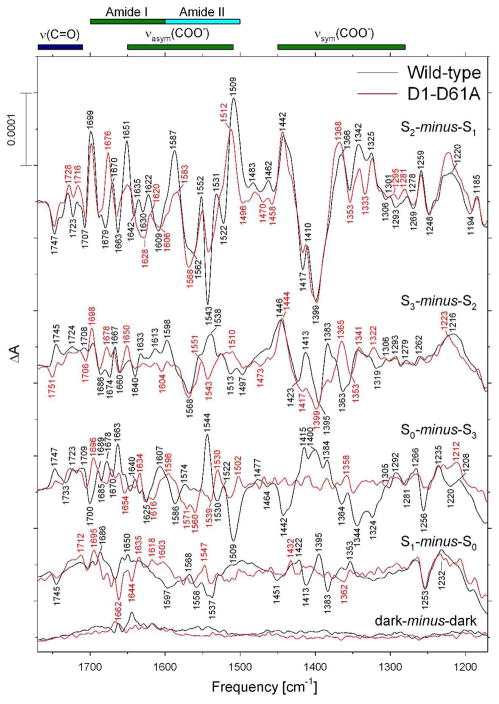

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of the mid-frequency FTIR difference spectra of wild-type (black) and D1-D61A (red) PSII core complexes in response four successive flash illuminations applied at 273 K. The wild-type spectra correspond predominantly to the S2-minus-S1, S3-minus-S2, S0-minus-S3, and S1-minus-S0 FTIR difference spectra, respectively. The data (plotted from 1770 cm−1 to 1170 cm−1) represent the averages of nine wild-type and eight D61A samples (10,800 and 9,600 scans, respectively). To facilitate comparisons, the mutant spectra have been multiplied by factors of ~ 1.1 after normalization to the peak-to-peak amplitudes of the negative ferricyanide peak at 2115 cm−1 and the positive ferricyanide peak at 2038 cm−1 to maximize overlap with the wild-type spectra. Dark-minus-dark control traces are included to show the noise level (lower traces).

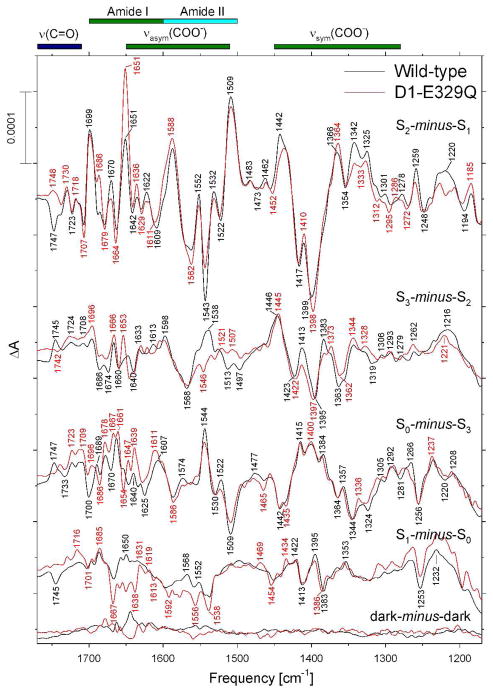

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of the mid-frequency FTIR difference spectra of wild-type (black) and D1-E329Q (red) PSII core complexes in response to four successive flash illuminations applied at 273 K. The data (plotted from 1770 cm−1 to 1170 cm−1) represent the averages of nine wild-type and four D1-D329Q samples (10,800 and 4,800 scans, respectively). The spectra have been normalized to the peak-to-peak amplitudes of the negative ferricyanide peak at 2115 cm−1 and the positive ferricyanide peak at 2038 cm−1. Dark-minus-dark control traces are included to show the noise level (lower traces).

Other Procedures

Chlorophyll concentrations and light-saturated, steady-state rates of O2 evolution were measured as described previously (69).

RESULTS

Wild-type PSII core complexes from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 frequently exhibit a negative band at 1747 cm−1 in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum (61, 64, 65, 70, 71) (Figure 1A, black trace). In this study, this band was altered or eliminated by a number of mutations of highly conserved carboxylate residues in the D1 and D2 polypeptides of Synechocystis 6803. The 1790 – 1710 cm−1 region contains the C=O carbonyl stretching mode [ν(C=O)] of protonated carboxylate residues (42, 43, 72) and also the keto and ester C=O vibrations of chlorophyll, pheophytin, heme, and lipids (73). In carboxylic acids, the C=O stretching and C–O–H bending modes of the COOH group are weakly coupled. This coupling is removed by deuteration, causing the ν(C=O) mode to downshift by 4 – 20 cm−1 (45, 47–49, 72). Accordingly, to test whether the 1747 cm−1 band corresponds to the ν(C=O) mode of a protonated carboxylate residue, the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectra of wild-type PSII core complexes was obtained after exchange into buffer containing D2O (Figure 1B). In D2O, the 1747 cm−1 mode appeared at 1743 cm−1, a downshift of 4 cm−1. Therefore, we attribute it to the ν(C=O) mode of a protonated carboxylate residue whose environment changes during the S1 to S2 transition (see discussion).

The negative (C=O) band at 1747 cm−1 is not observed in PSII core complexes from Thermosynechococcus elongatus (51, 66, 74–76) or PSII membranes from spinach (77–80). Nevertheless, we observe this feature consistently in PSII core complexes from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 when the samples are maintained at relative humidities of 99% (61, 62, 64, 65, 69) (Figure 1A, black trace) or 95% (not shown). The band has also been observed by others in PSII core complexes purified from the same organism (70). In the current study, the amplitude of the 1747 cm−1 band was diminished substantially at relative humitidies of 85% (Figure 1A, blue trace), 73% (not shown), or lower (i.e., when a dry film was placed in the sample cell, Figure 1A, red trace). Evidently, the degree of sample hydration is an important factor in the manifestation of this band. Interestingly, whereas other bands in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum are sensitive to the degree of sample hydration, none is altered as dramatically at the 1747 cm−1 band and many are relatively unperturbed by changes in the sample’s relative humidity (see below).

Exchange into D2O induced additional alterations to the wild-type S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum (Figure 1B). The D2O-induced alterations between 1700 and 1500 cm−1 resemble those reported previously in PSII membranes from spinach (78) and PSII core complexes from Thermosynechococcus elongatus (51). The apparent upshift of a negative band from 1561 to 1578 cm−1 was previously attributed to a D2O-induced shift of the νasym(COO−) mode of a carboxylate residue that accepts a strong hydrogen bond from a Mn-bound water molecule (78). The D2O-induced alterations to the amide I region, including the appearance of a positive band at 1636 cm−1, were previously attributed to D2O-induced changes in stretches of polypeptide having random coil conformations (78). The apparent upshift of the large positive feature at 1587 cm−1 to 1593 cm−1 is consistent with the D2O-induced upshift of the νasym(COO−) mode of another hydrogen-bonded carboxylate residue (78). The feature has been assigned to a νasym(COO−) mode because it downshifts by 30 – 35 cm−1 after global incorporation of 13C (63, 74, 81, 82), but is largely insensitive to global incorporation of 15N (63, 74, 82).

When the samples were maintained at a relative humidity of 85% or less, spectral alterations were present throughout the overlapping amide II/νasym(COO−) region and in the Amide I region, whereas few alterations were present elsewhere (except near 1747 cm−1, as described earlier). Some of the largest alterations were to the 1551(+), 1543(−), 1531(+), and 1522(−) cm−1 bands, whose amplitudes decreased substantially. The 1551(+) and 1543(−) bands were assigned previously to amide II modes because both downshift by 11 – 20 cm−1 after global incorporation of 13C or 15N (63, 74, 78, 81, 82). The 1531(+), and 1522(−) cm−1 bands downshift similarly (63, 74, 78, 81, 82) and presumably can also be assigned to amide II modes. A positive band at 1622 cm−1 also diminished substantially. This band downshifts significantly after global incorporation of 13C (63, 82), but not appreciably after global incorporation of 15N (63, 82), thereby identifying it as an amide I mode.

The D1-E239Q (83) and D2-E312A mutants examined in this study were photoautotrophic, whereas the D1-D61A and D1-E65A cells (84) were only weakly so. The O2 evolving activity of D2-E312A cells was 330 – 380 Ymol O2 (mg of Chl) −1 h−1 compared to 500 – 580 Ymol O2 (Yg of Chl) −1 h−1 for wild-type cells (i.e., 60 – 70% compared to wild-type). The O2 evolving activity of D1-D61A, D1-E65A, and D1-E329Q cells have been reported previously as ~ 19%, ~ 21%, and ~ 100% compared to wild-type, respectively (83, 84). The O2 evolving activities of the D1-D61A, D1-E65A, D1-E329Q, and D2-E312A PSII core particles examined in this study were ~ 870, ~ 730, ~ 3340, and ~ 1380 Ymol O2 (mg of Chl) −1 h−1 compared to 4900 – 5400 Ymol O2 (mg of Chl) −1 h−1 for wild-type. The O2 evolving activity of the D1-D61A PSII core complexes (~ 17% compared to wild-type) correlated with the lower O2 evolving activity of D1-D61A cells, but the O2 evolving activities of the D1-E65A, D1-E329Q, and D2-E312A PSII core complexes (~ 14 %, ~ 65%, and ~ 27%, respectively, compared to wild-type) were lower than in intact cells, suggesting either that the Mn4Ca clusters in D1-E65A, D1-E329Q, and D2-E312A cells are less stable than those in wild-type, or that the S state transitions proceed less efficiently in PSII core complexes purified from these mutants than in intact cells.

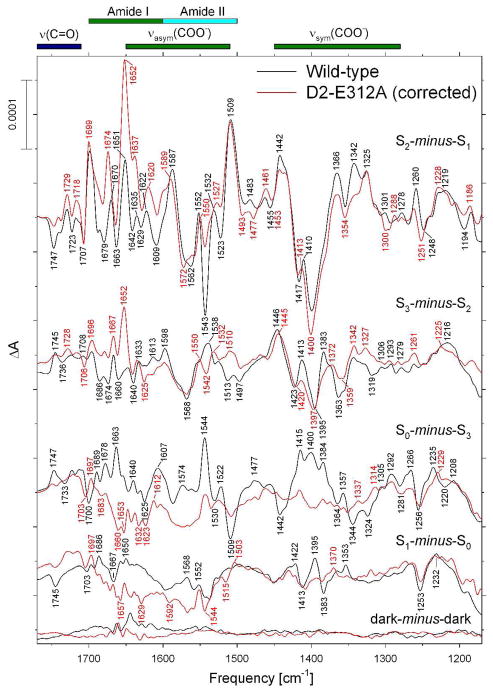

The mid-frequency FTIR difference spectra of wild-type and D1-D61A PSII core complexes that were induced by four successive flashes are compared in Figure 2 (black and red spectra, respectively). The spectra that were induced by the first, second, third, and fourth flashes given to the wild-type PSII core complexes correspond predominantly to the S2-minus-S1, S3-minus-S2, S0-minus-S3, and S1-minus-S0 FTIR difference spectra, respectively. These spectra closely resemble the Sn+1-minus-Sn difference spectra that have been reported previously for wild-type PSII core complexes from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (61, 63–65, 85). The S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum of D1-D61A PSII core complexes (upper red trace in Figure 2) showed substantial differences from the wild-type spectrum throughout the overlapping amide II/νasym(COO−) region. As was the case with partly dehydrated samples (Figure 1A), the bands at 1552(+), 1543(−), 1531(+), and 1522(−) cm−1 were diminished substantially. Positive bands at 1635, 1622, 1587, and 1509 cm−1 were also diminished substantially, with the 1587 cm−1 band being downshifted to 1583 cm−1 and the 1509 cm−1 band being upshifted to 1512 cm−1. The 1635 and 1622 cm−1 bands can be identified as amide I modes because both downshift significantly after global incorporation of 13C (63, 82), but not appreciably after global incorporation of 15N (63, 82). The 1552(+), 1543(−), 1531(+), and 1522(−) cm−1 bands can be identified as amide II modes because all four bands downshift appreciably after global incorporation of 13C (63, 74, 81, 82) or 15N (63, 74, 82). Similarly, the 1587 cm−1 band was previously assigned to a νasym(COO−) mode because it downshifts by 30 – 35 cm−1 after global incorporation of 13C (63, 74, 81, 82) but is largely insensitive to the global incorporation of 15N (63, 74, 82). The 1509 cm−1 band appears to consist of overlapping amide II and νasym(COO−) modes (63, 74, 82). Of particular importance to this study, the negative band at 1747 cm−1 was unaffected by the D1-D61A mutation.

The FTIR difference spectrum induced by the second flash applied to D1-D61A PSII core complexes contained some of the features that are present in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectra of wild-type (compare the upper two sets of black and red traces in Figure 2). These include bands at 1543(−), 1510(+), 1399(−), and 1365(+) cm−1. The presence of these bands shows that a significant fraction of D1-D61A PSII reaction centers failed to undergo the S2 to S3 transition following the second flash.

The FTIR difference spectra induced by the third and fourth flashes applied to D1-D61A PSII core complexes were practically devoid of features (lower two red traces in Figure 2). Typically, spectral features that appear during the S1 to S2 and S2 to S3 transitions in wild-type PSII are reversed during the S3 to S0 and S0 to S1 transitions (55–57). If large fractions of PSII reaction centers fail to advance between S states in response to saturating flashes, PSII reaction centers that undergo the S3 to S0 or S0 to S1 transitions after the third or fourth flashes may have their spectral features canceled by PSII reaction centers undergoing the S1 to S2 or S2 to S3 transitions after these flashes. The absence of clear, distinct peaks after the third and fourth flashes in D1-D61A PSII core complexes shows that a large fraction of D1-D61A PSII core complexes failed to advance beyond the S3 state in response to the these flashes.

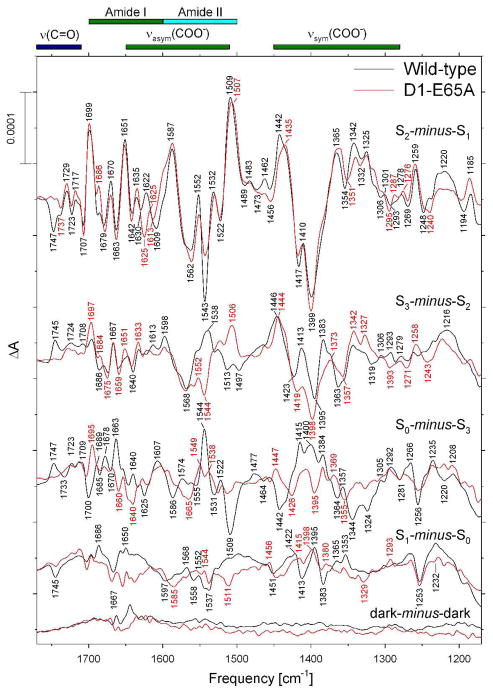

The mid-frequency FTIR difference spectra of wild-type and D1-E65A PSII core complexes that were induced by four successive flash illuminations are compared in Figure 3 (black and red spectra, respectively). The S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum of D1-E65A PSII core complexes (upper red trace in Figure 3) showed substantial differences from the wild-type spectrum throughout the overlapping amide II/νasym(COO−) region. As was the case with D1-D61A PSII core complexes, the positive bands at 1622 and 1552 cm−1 and the negative band at 1543 cm−1 were diminished substantially. As noted above, the 1622 cm−1 band corresponds to an amide I mode and the 1552 and 1543 cm−1 bands correspond to amide II modes. Of particular importance to this study, the negative band at 1747 cm−1 in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum of wild-type PSII core complexes was eliminated by the D1-E65A mutation (compare upper traces in Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of the mid-frequency FTIR difference spectra of wild-type (black) and D1-E65A (red) PSII core complexes in response to four successive flash illuminations applied at 273 K. The data (plotted from 1770 cm−1 to 1170 cm−1) represent the averages of nine wild-type and twelve D1-D61A samples (10,800 and 14,400 scans, respectively). To facilitate comparisons, the mutant spectra have been multiplied by factors of ~ 0.83 after normalization to the peak-to-peak amplitudes of the negative ferricyanide peak at 2115 cm−1 and the positive ferricyanide peak at 2038 cm−1 to maximize overlap with the wild-type spectra. Dark-minus-dark control traces are included to show the noise level (lower traces).

The FTIR difference spectrum induced by the second flash applied to D1-E65A PSII core complexes contained some of the features present in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectra of wild-type (compare the upper two sets of black and red traces in Figure 3). These include bands at 1544(−), 1506(+), 1398(−), and 1373(+) cm−1. The presence of these bands shows that a significant fraction of D1-E65A PSII reaction centers failed to undergo the S2 to S3 transition following the second flash. As was observed with D1-D61A, the spectra induced by the third and fourth flashes applied to D1-E65A PSII core complexes are nearly devoid of features (lower two red traces in Figure 3). Evidently, as was the case with D1-D61A, a large fraction of D1-E65A PSII core complexes fail to advance beyond the S3 state in response to saturating flashes.

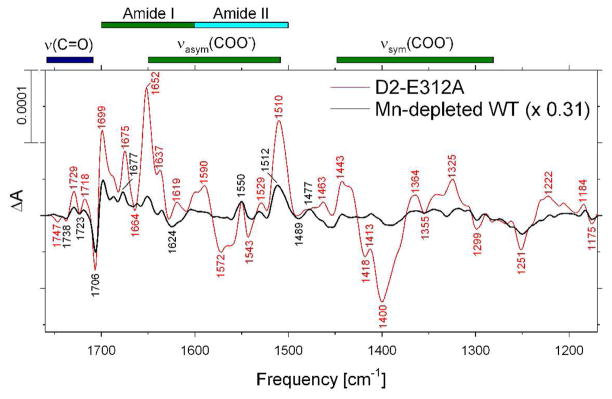

The mid-frequency FTIR difference spectrum of D2-E312A PSII core complexes that was induced by first of six successive flash illuminations is shown in Figure 4 (red spectrum). The presence of a large derivative feature at 1706(−)/1699(+) suggests that the D2-E312A PSII core complexes contain a significant fraction of PSII reaction centers that lack Mn4Ca clusters (61). The spectrum of Mn-depleted wild-type PSII core complexes obtained under conditions identical to those in the study (61) is shown for comparison (Figure 4, black trace). This spectrum corresponds to the YZ•-minus-YZ FTIR difference spectrum in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, whose primary features are positive peaks at 1699, 1677, 1651, 1550, 1521 and 1512 cm−1 and negative peaks at 1706, 1624, 1453, and 1250 cm−1 (86). To estimate the fraction of Mn-depleted PSII reaction centers in the D2-E312A PSII core complexes, the amplitudes of the negative 1706 cm−1 band in intact wild-type, Mn-depleted wild-type, and D2-E312A PSII core complexes were compared after normalizing all three spectra to the peak-to-peak amplitudes of the negative ferricyanide band at 2115 cm−1 and the positive ferrocyanide band at 2038 cm−1 (i.e., the spectra were normalized to the extent of flash-induced charge separation in each sample, as determined from the reduction of ferricyanide to ferricyanide by QA• −). On this basis, assuming that 0% of intact and 100% of Mn-depleted wild-type PSII core complexes lack Mn4Ca clusters, we estimated that ~ 31% of D2-E312A PSII core complexes lack Mn4Ca clusters (presumably the Mn4Ca clusters in D2-E312A cells are less stable than those in wild-type cells, despite the cluster’s distance from D2-Glu312). Accordingly, the first flash spectrum of the D2-E312A PSII core complexes was corrected by subtracting from it 31% of the spectrum of Mn-depleted wild-type PSII (61). No correction was applied to the second, third, or fourth flash spectra because Mn-depleted PSII makes no significant contribution to these spectra (61).

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of the mid-frequency FTIR difference spectra of Mn-depleted wild-type (black) and intact D2-E312A (red) PSII core complexes in response to the first of six successive flash illuminations applied at 273 K. The data (plotted from 1770 cm−1 to 1170 cm−1) represent the averages of nine Mn-depleted wild-type and nine D2-E312A samples (10,800 scans each). The fraction of D2-E312A PSII reaction centers lacking Mn4Ca clusters (0.31) was estimated from the amplitude negative peak at 1706 cm−1 (see text for details). Accordingly, the spectrum of the Mn-depleted wild-type sample shown in this figure was multiplied by a factor of 0.31 after normalization to the peak-to-peak amplitudes of the negative ferricyanide peak at 2115 cm−1 and the positive ferricyanide peak at 2038 cm−1.

The mid-frequency FTIR difference spectra of wild-type and D2-E312A PSII core complexes that were induced by four successive flash illuminations are compared in Figure 5 (black and red spectra, respectively). The corrected S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum of D1-E312A PSII core complexes (upper red trace in Figure 5) showed substantial differences from the wild-type spectrum throughout the overlapping amide II/νasym(COO−) region. As was the case with D1-D61A PSII core complexes, the bands at 1543(−), 1532(+), and 1523(−) cm−1 were diminished substantially. As noted earlier, the 1543(−) and 1532(+) bands can be identified as amide II modes on the basis of global labeling experiments. Other changes include increased amplitudes of bands at 1674, 1652, and 1637 cm−1 in the amide I region, a slight downshift of the positive band at 1622 cm−1 (assigned to an amide I mode, see above), and changes to amplitudes of bands in the symmetric carboxylate stretching region, including decreased amplitudes of positive bands at 1442, 1366, and 1342 cm−1 and an increased amplitude of the negative band at 1400 cm−1. Of particular importance to this study, the negative band at 1747 cm−1 in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum of wild-type PSII core complexes was eliminated by the D1-E312A mutation (compare upper traces in Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of the mid-frequency FTIR difference spectra of wild-type (black) and D2-E312A (red) PSII core complexes in response to four successive flash illuminations applied at 273 K. The data (plotted from 1770 cm−1 to 1170 cm−1) represent the averages of nine wild-type and nine D2-E312A samples (10,800 scans each). The S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum of D2-E312A was corrected for the presence of a significant population of Mn-depleted PSII reaction centers (see text for details). To facilitate comparisons, the mutant spectra have been multiplied by factors of ~ 1.4 after normalization to the peak-to-peak amplitudes of the negative ferricyanide peak at 2115 cm−1 and the positive ferricyanide peak at 2038 cm−1 to maximize overlap with the wild-type spectra. Dark-minus-dark control traces are included to show the noise level (lower traces).

The FTIR difference spectrum induced by the second flash applied to D2-E312A PSII core complexes contained some of the features present in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectra of wild-type (compare the upper two sets of black and red traces in Figure 5). These include bands at 1542(−), 1510(+), 1397(−), and 1372(+) cm−1. The presence of these bands shows that a significant fraction of D2-E312A PSII reaction centers failed to undergo the S2 to S3 transition following the second flash. As was the case with D1-D61A and D1-E65A, the spectra induced by the third and fourth flashes applied to D1-E312A PSII core complexes were nearly devoid of features (lower two red traces in Figure 5). Evidently, as was the case with D1-D61A and D1-E65A, a large fraction of D2-E312A PSII core complexes failed to advance beyond the S3 state in response to the these flashes.

The mid-frequency FTIR difference spectra of wild-type and D1-E329Q PSII core complexes that were induced by four successive flash illuminations are compared in Figure 6 (black and red spectra, respectively). The S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum of D1-E329Q PSII core complexes (upper red trace in Figure 6) showed many fewer differences from the wild-type spectrum than the other mutants. The differences included decreased amplitudes of bands at 1543(−), 1442(+), 1342(+) and 1220(+) cm−1, and increased amplitudes of bands at 1651(+), 1635(+), 1398(−), and 1364 (+) cm−1. As indicated previously, the 1543(−) and 1635(+) bands correspond to amide II and amide I modes, respectively. The 1442(+), 1364(+), and 1342(+) cm−1 bands correspond to νsym(COO−) modes because they downshifts by 20 – 45 cm−1 after global incorporation of 13C (63, 74, 81, 82) but are largely insensitive to the global incorporation of 15N (63, 74, 82).

The FTIR difference spectrum induced by the second flash given to D1-E329Q PSII core complexes contained some of the features present in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectra of wild-type PSII (compare the upper two sets of black and red traces in Figure 6). These include bands at 1546(−), 1397(−), and 1373(+) cm−1. The presence of these bands shows that a significant fraction of D1-E329Q PSII reaction centers failed to undergo the S2 to S3 transition following the second flash. However, in contrast to the other mutants examined in this study, the FTIR difference spectra induced by the third and fourth flashes resembled those of wild-type PSII core complexes. The primary differences were the slightly diminished amplitudes of the 1544(+) and 1509(−) bands in the S0-minus-S3 FTIR difference spectrum and the minor changes between 1667 and 1538 cm−1 in the S1-minus-S0 FTIR difference spectrum. Note the similarities between the S0-minus-S3 and S1-minus-S0 FTIR difference spectra of wild-type and D1-E329Q PSII core complexes between 1450 and 1350 cm−1 (compare the lower two pairs of black and red traces in Figure 6). Evidently, D1-E329Q PSII core complexes advance relatively efficiently between S states in response to saturating laser flashes, in marked contrast to the PSII core complexes of D1-D61A, D1-E65A, and D2-E312A. Of particular importance to this study, the negative band at 1747 cm−1 in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum of wild-type PSII core complexes was eliminated by the D1-E329Q mutation (compare upper traces in Figure 6).

It is noteworthy that the second flash spectra of D1-D61A, D1-E65A, D2-E312A, and D1-E329Q PSII core complexes resemble one another (Figures 2, 3, 5, 6). All four mutant spectra show similar deviations from the wild-type S3-minus-S2 FTIR difference spectrum, including negative features at 1546 – 1542 cm-1 and 1399 – 1397 cm−1 and positive features at 1510 – 1506 cm−1 and 1373 – 1365 cm−1. The similarities between the second flash spectra of all four mutants suggest that all four mutations decrease the efficiency of the S2 to S3 transition to similar extents. In contrast, the essentially featureless third and fourth flash spectra of D1-D61A, D1-E65A, and D2-E312A PSII core complexes show no resemblance to the third or fourth flash spectra of wild-type or D1-E329Q PSII core particles. Evidently, the D1-D61A, D1-E65A, and D2-E312A mutations decrease the efficiency of the S3 to S0 transition far more substantially than they decrease the efficiency of the S2 to S3 transition.

DISCUSSION

One of the most striking results of the FTIR studies on PSII to date is the stunning insensitivity of the individual FTIR difference spectra to the mutation of at least three of the Mn4Ca cluster’s six putative carboxylate ligands. Not only do mutations of D1-Asp170 (64, 87), D1-Glu189 (65, 88), and D1-Asp342 (61) fail to eliminate any carboxylate vibrational stretching modes, they fail to produce significant changes in polypeptide backbone conformations as shown by the lack of significant mutation-induced alterations to the amide I and amide II regions of the spectra. This result was entirely unexpected. The individual FTIR difference spectra of wild-type PSII core complexes contain a wealth of spectral features. It had long been assumed that most of these features would correspond to amino acid residues that ligate the Mn4Ca cluster. Whereas some of these features clearly correspond to first coordination sphere ligands [i.e., CP43-Glu354 (71, 85) and the α-COO− group of D1-Ala344 (62, 69, 89)], the majority of these features evidently correspond to residues in the cluster’s second coordination sphere and beyond. These features must reflect the response of the protein to the electrostatic influences that arise from the positive charge that develops on the Mn4Ca cluster during the S1 to S2 transition and to the structural changes that are associated with the S2 to S3, S3 to S0, and S0 to S1 transitions.

The simplest explanation for the insensitivity of the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum to the individual mutation of most the cluster’s putative carboxylate ligands is that the positive charge that develops on the Mn4Ca cluster during this transition is highly delocalized at ambient temperatures. There is ample precedent for such delocalization in mixed-valence inorganic metal complexes (90–92). Such delocalization would be consistent with a comparative inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) study of Mn oxides, Mn coordination complexes, and spinach PSII membranes (93). The authors of this study concluded that the electron that leaves the Mn4Ca cluster during the S1 to S2 transition originates from a highly delocalized orbital (93). Delocalization would also be consistent with QM/MM analyses that have been based on the 3.5 Å X-ray crystallographic structural model (7, 22, 27, 94). The authors of these studies concluded that the oxidation of the Mn4Ca cluster during the S1 to S2 transition would cause little increase in the electrostatic charge of the individual Mn ions. In their analyses, the greatest increase in electrostatic charge during this transition is actually on the Ca ion. These authors also proposed that the α-COO− group of D1-Ala344 is a unidentate ligand of Ca. However, a recent 13C-ENDOR study shows that this group ligates Mn (95) (ligation of both Mn and Ca is possible), consistent with the 3.0 Å and 2.9 Å crystallographic structural models (2, 5) and with an earlier FTIR study involving the replacement of Ca with Sr (62). The QM/MM analyses also predict that CP43-Glu354 ligates along the Jahn-Teller axis of a Mn(III) ion (7, 22, 27, 94). On the basis of recent FTIR studies, it has been proposed that CP43-Glu354 changes its coordination mode during the S1 to S2 transition (85) [but see (71)] and that D1-Ala344 significantly changes its orientation (96). Consequently, the reason that both the νsym(COO−) mode of D1-Ala344 (62, 69, 89) and the νasym(COO−) mode of CP43-Glu354 (71, 85) shift during the S1 to S2 transition may be that the carboxylate group of one ligates along the Jahn-Teller axis of the Mn(III) ion that undergoes oxidation and the carboxylate group of the other changes its coordination mode or orientation.

Most of the Mn4Ca cluster’s putative carboxylate ligands appear to facilitate the cluster’s assembly (97, 98) rather than regulate its function: D1-Asp170, Glu189, and D1-Asp342 each can be replaced by at least one other amino acid that supports significant O2 producing activity (20, 99–101). In contrast, residues in Mn4Ca cluster’s second coordination sphere and beyond are postulated to play key roles in providing the driving force for oxidizing the cluster in its higher oxidation states and in regulating the access of substrate water. In particular, recent models postulate that CP43-Arg357 (or D1-Asp61) serves as a redox-activated catalytic base that facilitates the oxidation of the Mn4Ca cluster during the S2 to S3 and S3 to S4 transitions (7, 13, 21, 22, 25–28). In these models, when the Mn4Ca cluster is in its S2 or S3 states, the formation of YZ• triggers the deprotonation of CP43-Arg357 (or D1-Asp61) to the thylakoid lumen. Protonation to the lumen is necessary from energetic considerations (102). The subsequent oxidation of the Mn4Ca cluster involves the simultaneous transfer of a proton from the Mn4Ca cluster to the now deprotonated CP43-Arg357 (or D1-Asp61). In these models, the pKA of CP43-Arg357 (or D1-Asp61) is decreased substantially by the presence of the positive charge on the YZ•/D1-His190 pair (hence the formation of YZ• triggers the residue’s deprotonation). The pKA value is restored when the charge on the YZ•/D1-His190 pair is neutralized by electron transfer from the Mn4Ca cluster to YZ•. Hence, the reprotonation of CP43-Arg357 (or D1-Asp61) is highly favored and provides a strong thermodynamic driving force for oxidizing the Mn4Ca cluster in its higher oxidation states. The initial, YZ•-induced deprotonation of CP43-Arg357 (or D1-Asp61) requires its deprotonation to the lumen via a network of protonatable amino acid side chains and water molecules such as those envisaged to exist in the potential proton egress channels that have been identified in the X-ray crystallographic structural models (1, 5, 32–35). Kinetically efficient proton transfer through these channels requires finely tuned pKA differences between key residues and transient formation of clusters of water molecules (102–105). Consequently, mutation of key residues in a dominant proton egress pathway would be expected to slow oxidation of the Mn4Ca cluster in the same manner that mutations that impair proton uptake slow electron transfer to from QA•− to QB•− in reaction centers of Rhodobacter sphaeroides (37–39) and the reduction of O2 to H2O in cytochrome c oxidase (106–108). In support of their proposed roles in proton transfer, mutations of D1-Asp61 (109–111) and CP43-Arg357 (112, 113) slow oxidation of the Mn4Ca cluster substantially during one or more of the S state transitions.

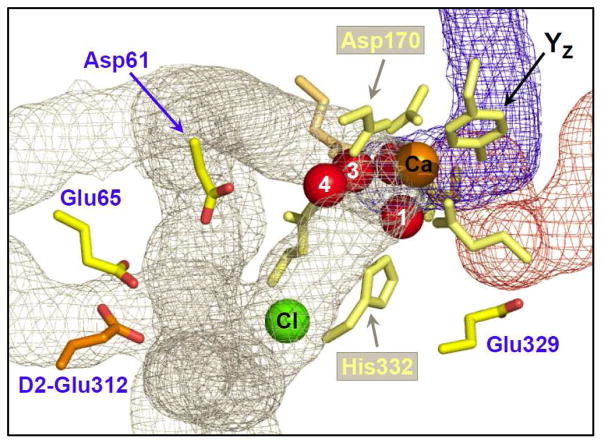

As an initial attempt to verify the proposed proton egress channels in PSII experimentally, we have used the negative band at 1747 cm−1 in the wild-type S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum to probe for the presence of a network of hydrogen bonds near the Mn4Ca cluster. The residues D1-Asp61, D1-Glu65, D2-Glu312, and D1-Glu329 are highly conserved and are the closest carboxylate residues to the Mn4Ca cluster that do not ligate Mn or Ca (1, 2, 5). In the 2.9 Å crystallographic structural model, these residues are located 4.6 Å, 10.8 Å, 11.3 Å, and 7.5 Å from the nearest Mn ion, respectively (5) (Figure 7). The peptide carbonyl of D1-Glu329 accepts a hydrogen bond from D1-His332, a putative Mn ligand. The side chain of D1-Glu329 has been proposed to participate in an O2 egress channel (5, 35), while the side chains of D1-Asp61, D1-Glu65, and D2-Glu312 have been proposed participate in a proton egress channel (1, 5, 32–35) with D1-Glu65 located at the channel’s narrowest point (5, 35).

FIGURE 7.

The Mn4Ca cluster and its environment as depicted in the 2.9 Å crystallographic structural model of PSII from Thermosynechococcus elongatus (3BZ1) (5). The four residues discussed in this panel are depicted in bright yellow (Asp61, Glu65, and Glu329 of the D1 polypeptide) or bright orange (Glu312 of the D2 polypeptide). The Mn, Ca, and Cl ions are depicted as red, orange, and green spheres, respectively. Tyrosine YZ and the protein ligands of the Mn4Ca cluster are depicted in light yellow or orange (residues of D1 and CP43, respectively). Portions of water access, proton egress, and O2 egress channels identified in the 2.9 Å structural model are depicted in blue, gray, and maroon, respectively (the channel coordinates from ref. (35) were graciously provided by A. Zouni). In this model, the shortest distances between the carboxylate group and the nearest Mn ion is 4.6 Å, 10.8 Å, 11.3 Å, and 7.5 Å for D1-Asp61, D1-Glu65, D2-Glu312, and D1-Glu329, respectively (5).

Our data show that the D1-D61A, D1-E65A, and D2-E312A mutations perturb the properties of the Mn4Ca cluster far more than do mutations of the putative Mn ligands D1-Asp170, D1-Glu189, and D1-Asp342. The fraction of PSII reaction centers that advance through the S state cycle in response to saturating flashes is substantially diminished in PSII core complexes from all three mutants (Figures 2, 3, and 5). In all three mutants, the efficiency of the S2 to S3 transition is lower than in wild-type and the efficiency of the S3 to S0 transition appears to be substantially lower. The latter point is best illustrated by comparing the second and third flash spectra of D1-E329Q with the corresponding data of D1-D61A, D1-E65A, and D2-E312A. Whereas the efficiency of the S2 to S3 transition appears to be decreased to similar extents in all four mutants, the efficiency of the S3 to S0 transition is much lower in D1-D61A, D1-E65A, and D2-E312A than in D1-E329Q. In contrast, D1-D170H, D1-E189Q, D1-E189R, and D1-D342N PSII core complexes advance efficiently through the S state cycle, with no apparent decrease in the efficiency of any S state transition (61, 64, 65). A substantially decreased efficiency for the S3 to S0 transition in D1-D61A PSII core complexes would be consistent with earlier data showing that the rate of O2 release is slowed eight-fold in D1-D61A cells (109). The D1-D61N mutation also decreases the efficiency of the S state transitions and slows the rate of O2 release ten-fold (109). In D1-D61N PSII core complexes, the S1 to S2 and S2 to S3 transitions are slowed two-fold (109) and the S3 to S0 transition is slowed ten-fold (110). A similar slowing of the S state transitions is likely to occur in D1-D61A PSII core complexes, and by inference, in D1-E65A and D2-E312A PSII core complexes. Slowed oxidation of the Mn4Ca cluster during the S state transitions would be consistent with a role for all three residues in a dominant postulated proton egress pathway linking the Mn4Ca cluster with the thylakoid lumen, such as those identified in analyses of the existing X-ray crystallographic structural models (1, 5, 32–35).

The S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectra of D1-D61A, D1-E65A, D2-E312A, and D1-E329Q PSII core complexes are altered far more than the corresponding spectra of D1-D170H, D1-E189Q, and D1-D342N PSII core complexes. Several amide II modes are altered substantially in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectra of D1-D61A, D1-E65A, and D2-E312A. These alterations show that these mutations alter the conformational rearrangements of the polypeptide backbone that normally accompany the S1 to S2 transition. Evidently, the D1-D61A, D1-E65A, and D2-E312A mutations substantially alter part of the protein’s structural response to the increased charge that develops on the Mn4Ca cluster during this transition. The D1-E329Q mutation evidently alters this response to a much lesser extent because only the negative amide II mode at 1543 cm−1 is affected significantly.

The primary focus of this study is on the negative band at 1747 cm−1. This band is observed in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum of moderately-hydrated wild-type PSII core complexes (Figure 8). This band is eliminated by partial dehydration (Figure 8A). It is also eliminated by the D1-E65A, D2-E312A, and D1-E329Q mutations (Figures 8D-F). In contrast, it is unaltered by the D1-D61A mutation (Figure 8C). The elimination of this mode does not correlate with substantial changes in the protein’s structural response to the S1 to S2 transition because it is present in D1-D61A and absent in D1-E329Q. In carboxylic acids, deuteration removes the weak coupling that exists between the C=O stretching and C–O–H bending modes of the COOH group, causing the ν(C=O) mode to downshift by 4 – 20 cm−1 (45, 47–49, 72). This D2O-induced downshift is diagnostic for the ν(C=O) mode of protonated carboxylate residues and has been used as such in many systems, including bacteriorhodopsin (45, 114–117), rhodopsin (118, 119), bacterial reaction centers (120–123), heme-copper oxidases (124–127) and photoactive yellow protein (128). Exchange of wild-type PSII core complexes into buffer containing D2O downshifted the 1747 cm−1 band by 4 cm−1 (Figure 8B). Deuteration-induced downshifts of 4 cm−1 have been reported previously for the ν(C=O) mode of Asp212 in bacteriorhodopsin (117), Glu L212 in bacterial reaction centers (121), and Glu278 in cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans (124, 126) [also see (125)]. On the basis of its downshift in D2O, we attribute the negative 1747 cm−1 band to the ν(C=O) mode of a protonated carboxylate residue whose environment changes during the S1 to S2 transition.

FIGURE 8.

The ν(C=O) region of the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectra of (A) wild-type PSII core complexes maintained at a relative humidity of 99% (black) or 85% (blue) or as a dry film in the sample cell (red), (B) wild-type PSII core complexes exchanged into FTIR buffer containing H2O (black) or D2O (red), (C) wild-type (black) and D1-D61A (red) PSII core complexes, (D) wild-type (black) and D1-E65A (red) PSII core complexes, (E) wild-type (black) and D1-E312A (red) PSII core complexes (after correction of D2-E312A for the presence of Mn-depleted reaction centers – see text for details), and (F) wild-type (black) and D1-E329Q (red) PSII core complexes. The data have been reproduced from Figures 1A, 1B, 2, 3, 5, and 6, respectively.

The frequency of the ν(C=O) mode of a carboxylic acid residue depends on the number and strengths of hydrogen bonds involving the C=O and O–H groups (45, 47–49, 72). Its appearance at 1747 cm−1 in wild-type PSII core complexes suggests that it participates in a single hydrogen bond that involves the C=O group (48, 49), although participation in two hydrogen bonds, with one involving the C-O-H oxygen, cannot be excluded (49). In an FTIR difference spectrum, the peak corresponding to the ν(C=O) mode of a carboxylic acid residue can change in a number of ways. Partial protonation (deprotonation) of an Asp or Glu residue gives rise to a single positive (negative) absorption band. Proton transfer between two Asp/Glu residues gives rise to positive and negative bands of approximately equal amplitudes (assuming that the two ν(C=O) modes are well separated). A change in the environment of a carboxylic acid causes the band to shift and gives rise to a differential band. The shape of the negative 1747 cm−1 peak in wild-type PSII core complexes suggests that a carboxylate residue partly deprotonates (i.e., its pKA decreases) in response to the S1 to S2 transition. The partial depronation of this residue should increase the amplitudes of the νasym(COO−) and νsym(COO−) modes of the same residue in its carboxylate form. These modes should appear near 1580 – 1560 cm−1 and 1400 cm−1, respectively (72). Consequently, the loss of the negative peak at 1747 cm−1 should correlate with a loss of positive spectral features (or the increase of negative spectral features) near 1580 – 1560 cm−1 and 1400 cm−1. Although decreased positive amplitude at 1587 cm−1 is observed in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum of partly dehydrated wild-type PSII (blue and red traces in Figure 1A), the same change is not observed in D1-E65A, D2-E312A, or D1-E329Q (top traces in Figures 3, 5, and 6, respectively). Similarly, while increased negative amplitude at near 1400 cm−1 is observed in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectra of D1-E65A, D2-E312A, and D1-E329Q (Figures 3, 5, and 6), the same change is not observed in partly-dehydrated wild-type (Figure 1A). We presume that the expected changes to the νasym(COO−) and νsym(COO−) modes are masked by other mutation-induced or dehydration-induced structural changes in these regions.

The structural response of PSII to the development of charge on the Mn4Ca cluster during the S1 to S2 transition presumably is propagated both electrostatically and through networks of hydrogen bonds involving amino acid residues and water molecules. We propose that this propagated structural response alters the environment of the carboxylate group responsible for the 1747 cm−1 band, decreasing this group’s pKA value. We also propose that D1-Glu65, D2-Glu312, and D1-Glu329 participate in the same network of hydrogen bonds as the carboxylate group responsible for this band. Finally, we propose that the mutation of any of these three residues to a non-protonatable residue, or the partial dehydration caused by maintaining samples at a relative humidity of 85% or less, disrupts the network sufficiently that the structural perturbations associated with S1 to S2 transition are no longer transmitted to this carboxylate, thereby eliminating the 1747 cm−1 band from the spectrum. The carboxylate group that corresponds to the 1747 cm−1 band could be the side chain of D1-Glu65, D2-Glu312, or D1-Glu329. Alternatively, it could belong to another carboxylate residue located in the same proposed network of hydrogen bonded side chains and water molecules. Because the side chain of D1-Glu329 is located ~ 20 Å from D1-Glu65 and D2-Glu312 in the 2.9 Å crystallographic structural model (5), the extended network of hydrogen bonds identified in this study must extend for at least 20 Å across the lumenal face of the Mn4Ca cluster and probably includes the chloride ion identified in this model. The existence of extensive networks of hydrogen bonds in the lumenal domains of PSII was predicted recently on the basis of a molecular dynamics study (36). Because mutations of D1-Asp61, D1-Glu65, and D2-Glu312 substantially decrease the fraction of PSII reaction centers that undergo the S3 to S0 transition in response to a saturating flash, the hydrogen-bonded network that includes these residues may form part of a dominant proton egress pathway leading from the Mn4Ca cluster to the thylakoid lumen. In is noteworthy that D1-Glu329 does not form part of the same putative access/egress channel as D1-Asp61, D1-Glu65, and D2-Glu312 in recent analyses of static PSII structures (1, 5, 32–35). It is an open question whether features of this network, particularly the apparent connection between D1-Glu329 and the other three residues, exist permanently or fleetingly, like the networks of hydrogen bonds that transiently connect hydrophilic pockets in the recent molecular dynamics study (36).

In the 2.9 Å crystallographic structural model, the side chain of D1-Asp61 is located only 4.8 Å from the side chain of D1-Glu65 and only 6.4 Å from the side chain of D2-Glu312 (5). Furthermore, D1-Asp61 is located between the Mn4Ca cluster and both of these residues. Consequently, it seems likely that D1-Asp61 participates in the same network of hydrogen bonds as D1-Glu65, D2-Glu312, and D1-Glu329. Nevertheless, the 1747 cm−1 band is unaltered by the mutation of D1-Asp61 to Ala. This lack of an effect provides a constraint on attempts to identify the source of the 1747 cm−1 band and suggests that the carboxylate residue that gives rise to this band is located closer to D1-Glu65, D2-Glu312, or D1-Glu329 than to D1-Asp61. Possible candidates include D2-Glu302, D2-Glu308, D2-Glu310, D2-Glu323, PsbO-Asp184, and PsbO-Asp250.

Comparison of the individual FTIR difference spectra of wild-type PSII core particles (e.g., Figure 2, black traces) shows that the negative band at 1747 cm−1 in the S2-minus-S1 spectrum appears to correlate with a positive band at 1747 cm−1 in the S0-minus-S3 spectrum and that a positive band at 1745 cm−1 in the S3-minus-S2 spectrum appears to correlate with a negative band at 1745 cm−1 in the S1-minus-S0 spectrum. It is tempting to speculate that the structural perturbations responsible for the negative 1747 cm−1 band during the S1 to S2 transition are reversed during the S3 to S0 transition and that another carboxylate group has its pKA increased during the S2 to S3 transition and restored during the S0 to S1 transition. It is interesting to note that the 1745 cm−1 band was eliminated by all four mutants examined in this study. However, conclusions regarding the reversibility of the 1747 cm−1 band and the nature of the 1745 cm−1 band must await D2O-exchange analysis of the S3-minus-S2, S0-minus-S3, and S1-minus-S0 transitions in wild-type PSII core complexes.

In PSII core complexes from the cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus, the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum contains no large negative features at 1747 cm−1 (51, 66, 74–76). Furthermore, the exchange of T. elongatus PSII core complexes into D2O produces no downshift of any mode in the ν(C=O) region (51). The band is also absent from the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum of spinach PSII membranes (77–80), although a positive band at 1747 cm−1 was reported in spinach PSII core complexes (129). Exchange of spinach PSII membranes into D2O also produces no downshift of any mode in the ν(C=O) region (78). One possible explanation for the lack of this band in T. elongatus and spinach PSII preparations derives from the slight differences between the amino acid sequences of the PSII polypeptides of spinach, T. elongatus, and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Because the sequences differ, the orientations of side chains and water molecules in the extended network of hydrogen bonds are likely to differ. Perhaps these networks differ to the extent that the structural perturbations associated with the S1 to S2 transition in T. elongatus and spinach are not transmitted to the carboxylate group that is responsible for the 1747 cm−1 band in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. The sensitivity of this band to the extent of sample hydration and to the mutation of selected single amino acid residues shows the sensitivity of the corresponding carboxylate group to minor changes in protein environment. Alternatively, this carboxylate residue may not be conserved in all organisms. However, a third explanation is that the observation of this band is preparation-dependent. For example, this band has been reported previously in some PSII preparations from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (61, 62, 64, 65, 69, 70), but not in others (85, 87–89, 130). Nevertheless, we have observed it under a variety of conditions, including in PSII core complexes that have been purified in the presence of 25% (v/v) glycerol instead of 1.2 M betaine.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

On the basis of the presence or absence of the ν(C=O) mode of a protonated carboxylate group in the S2-minus-S1 FTIR difference spectrum, we conclude that the residues D1-Glu65, D1-Glu329, and D2-Glu312 participate in a hydrogen-bonded network that extends at least 20 Å across the lumenal face of the Mn4Ca cluster. This network presumably also includes D1-Asp61. The D1-D61A, D1-E65A, and D2-E312A mutations appear to substantially decrease the fraction of PSII reaction centers that undergo the S3 to S0 transition in response to a saturating flash. Consequently, elements of the hydrogen-bonded network that includes D1-Asp61, D1-Glu65, D2-Glu312, and D1-Glu329 may comprise part of a dominant proton egress pathway leading from the Mn4Ca cluster to the thylakoid lumen.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Melodie A. Strickler for assistance during the initial phase of this study and to Anh P. Nguyen for maintaining the mutant and wild-type cultures of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and for purifying the thylakoid membranes that were used for the isolation of the PSII core complexes. We also thank Athina Zouni and Azat Gabdulkhakov for providing the coordinates for the substrate/product channels included in Figure 7.

Abbreviations

- Chl

chlorophyll

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- EXAFS

extended X-ray absorption fine structure

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid

- NTA

nitrilotriacetic acid

- P680

chlorophyll multimer that serves as the light-induced electron donor in PSII

- Pheo

pheophytin

- PSII

photosystem II

- QA

primary plastoquinone electron acceptor

- QB

secondary plastoquinone electron acceptor

- RH

relative humidity

- XANES

X-ray absorption near edge structure

- YZ

tyrosine residue that mediates electron transfer between the Mn4Ca cluster and P680+•

- YD

second tyrosine residue that can reduce P680+• in PSII

Footnotes

Support for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (GM 076232 to R. J. D.) and by the Australian Research Council (FT0990972 to W. H.)

References

- 1.Ferreira KN, Iverson TM, Maghlaoui K, Barber J, Iwata S. Architecture of the Photosynthetic Oxygen-Evolving Center. Science. 2004;303:1831–1838. doi: 10.1126/science.1093087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loll B, Kern J, Saenger W, Zouni A, Biesiadka J. Towards Complete Cofactor Arrangement in the 3.0 Å Resolution Structure of Photosystem II. Nature. 2005;438:1040–1044. doi: 10.1038/nature04224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kern J, Biesiadka J, Loll B, Saenger W, Zouni A. Structure of the Mn4-Ca Cluster as Derived from X-ray Diffraction. Photosyn Res. 2007;92:389–405. doi: 10.1007/s11120-007-9173-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber J. Crystal Structure of the Oxygen-Evolving Complex of Photosystem II. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:1700–1710. doi: 10.1021/ic701835r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guskov A, Kern J, Gabdulkhakov A, Broser M, Zouni A, Saenger W. Cyanobacterial Photosystem II at 2.9-Å Resolution and the Role of Quinones, Lipids, Channels, and Chloride. Nature Struct & Mol Biol. 2009;16:334–342. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guskov A, Gabdulkhakov A, Broser M, Glöckner C, Hellmich J, Kern J, Frank J, Müh F, Saenger W, Zouni A. Recent Progress in the Crystallographic Studies of Photosystem II. ChemPhysChem. 2010;11:1160–1171. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McEvoy JP, Brudvig GW. Water-Splitting Chemistry of Photosystem II. Chem Rev. 2006;106:4455–4483. doi: 10.1021/cr0204294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarrick RM, Britt RD. Current Models and Mechanism of Water Splitting. In: Fromme P, editor. Photosynthetic Protein Complexes. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; Weinheim, Germany: 2008. pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rappaport F, Diner BA. Primary Photochemistry and Energetics Leading to the Oxidation of the (Mn)4Ca Cluster and to the Evolution of Molecular Oxygen in Photosystem II. Coord Chem Rev. 2008;252:259–272. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renger G, Renger T. Photosystem II: The Machinery of Photosynthetic Water Splitting. Photosynth Res. 2008;98:53–80. doi: 10.1007/s11120-008-9345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yano J, Yachandra VK. Where Water is Oxidized to Dioxygen: Structure of the Photosynthetic Mn4Ca Cluster from X-ray Spectroscopy. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:1711–1726. doi: 10.1021/ic7016837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yano J, Yachandra VK. Oxidation State Changes of the Mn4Ca Cluster in Photosystem II. Photosynth Res. 2007;92:289–303. doi: 10.1007/s11120-007-9153-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dau H, Haumann M. The Manganese Complex of Photosystem II in its Reaction Cycle - Basic Framework and Possible Realization at the Atomic Level. Coord Chem Rev. 2008;252:273–295. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sauer K, Yano J, Yachandra VK. X-ray Spectrsocopy of the Photosynthetic Oxygen-Evolving Complex. Coord Chem Rev. 2008;252:318–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray JW, Maghlaoui K, Kargul J, Ishida N, Lai TL, Rutherford AW, Sugiura M, Boussac A, Barber J. X-ray Crystallography Identifies two Chloride Binding Sites in the Oxygen Evolving Centre of Photosystem II. Energy Environ Sci. 2008;1:161–166. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawakami K, Umena Y, Kamiya N, Shen JR. Location of Chloride and its Possible Functions in Oxygen-Evolving Photosystem II Revealed by X-ray Crystallography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8567–8572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812797106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yano J, Kern J, Irrgang KD, Latimer MJ, Bergmann U, Glatzel P, Pushkar Y, Biesiadka J, Loll B, Sauer K, Messinger J, Zouni A, Yachandra VK. X-ray Damage to the Mn4Ca Complex in Single Crystals of Photosystem II: A Case Study for Metalloprotein Crystallography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12047–12052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505207102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grabolle M, Haumann M, Müller C, Liebisch P, Dau H. Rapid Loss of Structural Motifs in the Manganese Complex of Oxygenic Photosynthesis by X-ray Irradiation at 10–300 K. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4580–4588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yano J, Kern J, Sauer K, Latimer MJ, Pushkar Y, Biesiadka J, Loll B, Saenger W, Messinger J, Zouni A, Yachandra VK. Where Water is Oxidized to Dioxygen: Structure of the Photosynthetic Mn4Ca Cluster. Science. 2006;314:821–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1128186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Debus RJ. Protein Ligation of the Photosynthetic Oxygen-Evolving Center. Coord Chem Rev. 2008;252:244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dau H, Haumann M. Time Resolved X-ray Spectroscopy Leads to an Extension of the Classical S-State Cycle Model of Photosynthetic Oxygen Evolution. Photosynth Res. 2007;92:327–343. doi: 10.1007/s11120-007-9141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sproviero EM, Gascón JA, McEvoy JP, Brudvig GW, Batista VS. Computation Studies of the O2-Evolving Complex of Photosystem II and Biomimetic Oxomanganese Complexes. Coord Chem Rev. 2008;252:395–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wydrzynski T, Hillier W, Messinger J. On the Functional Significance of Substrate Accessibility in the Photosynthetic Water Oxidation Mechanism. Physiol Plant. 1996;96:342–350. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson JM. Does Functional Photosystem II Complex have an Oxygen Channel? FEBS Lett. 2001;488:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McEvoy JP, Brudvig GW. Structure-Based Mechanism of Photosynthetic Water Oxidation. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2004;6:4754–4763. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haumann M, Liebisch P, Müller C, Barra M, Grabolle M, Dau H. Photosynthetic O2 Formation Tracked by Time-Resolved X-ray Experiments. Science. 2005;310:1019–1021. doi: 10.1126/science.1117551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sproviero EM, Gascón JA, McEvoy JP, Brudvig GW, Batista VS. Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics Study of the Catalytic Cycle of Water Splitting In Photosystem II. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:3428–3442. doi: 10.1021/ja076130q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sproviero EM, McEvoy JP, Gascón JA, Brudvig GW, Batista VS. Computational Insights into the O2-Evolving Complex of Photosystem II. Photosynth Res. 2008;97:91–114. doi: 10.1007/s11120-008-9307-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barber J, Ferreira KN, Maghlaoui K, Iwata S. Structural Model of the Oxygen-Evolving Centre of Photosystem II with Mechanistic Implications. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2004;6:4737–4742. [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Las Rivas J, Barber J. Analysis of the Structure of the PsbO Protein and Its Implications. Photosynth Res. 2004;81:329–343. doi: 10.1023/B:PRES.0000036889.44048.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shutova T, Klimov VV, Andersson B, Samuelsson G. A Cluster of Carboxylic Groups in PsbO Protein is Involved in Proton Transfer from the Water Oxidizing Complex of Photosystem II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1767:434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishikita H, Saenger W, Loll B, Biesiadka J, Knapp E-W. Energetics of a Possible Proton Exit Pathway for Water Oxidation in Photosystem II. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2063–2071. doi: 10.1021/bi051615h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho FM, Styring S. Access Channels and Methanol Binding Site to the CaMn4 Cluster in Photosystem II based on Solvent Accessibility Simulation, with Implications for Substrate Water Access. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:140–153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray JW, Barber J. Structural Characteristics of Channels and Pathways in Photosystem II Including the Identification of an Oxygen Channel. J Struct Biol. 2007;159:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabdulkhakov A, Guskov A, Broser M, Kern J, Müh F, Saenger W, Zouni A. Probing the Accessibility of the Mn4Ca Cluster in Photosystem II: Channels Calculation, Noble Gas Derivatization, and Cocrystallization with DMSO. Structure. 2009;17:1223–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vassiliev S, Comte P, Mahboob A, Bruce D. Tracking the Flow of Water through Photosystem II Using Molecular Dynamics and Streamline Tracing. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1873–1881. doi: 10.1021/bi901900s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okamura MY, Paddock ML, Graige MS, Feher G. Proton and electron transfer in bacterial reaction centers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1458:148–163. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paddock ML, Feher G, Okamura MY. Proton Transfer Pathways and Mechanism in Bacterial Reaction Centers. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wraight CA. Intraprotein Proton Transfer - Concepts and Realities from the Bacterial Photosynthetic Reaction Center. In: Wikström M, editor. Biophysical and Structural Aspects of Bioenergetics. RSC Publishing; Cambridge, UK: 2005. pp. 273–313. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zscherp C, Barth A. Reaction-Induced Infrared Difference Spectroscopy for the Study of Protein Reaction Mechanisms. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1875–1883. doi: 10.1021/bi002567y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barth A, Zscherp C. What Vibrations Tell Us About Proteins. Q Rev Biophys. 2002;35:369–430. doi: 10.1017/s0033583502003815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rich PR, Iwaki M. Infrared Protein Spectroscopy as a Tool to Study Protonation Reactions Within Proteins. In: Wikström M, editor. Biopysical and Structural Aspects of Bioenergetics. Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge, U.K.: 2005. pp. 314–333. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barth A. Infrared Spectroscopy of Proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1767:1073–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berthomieu C, Hienerwadel R. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy. Photosynth Res. 2009;101:157–170. doi: 10.1007/s11120-009-9439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]