Abstract

Raman spectroscopy, based on the inelastic scattering of a photon, has been widely used as an analytical tool in many research fields. Recently, Raman spectroscopy has also been explored for biomedical applications (e.g. cancer diagnosis) because it can provide detailed information on the chemical composition of cells and tissues. For imaging applications, several variations of Raman spectroscopy have been developed to enhance its sensitivity. This review article will provide a brief summary of Raman spectroscopy-based imaging, which includes the use of coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy (CARS, primarily used for imaging the C-H bond in lipids), surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS, for which a variety of nanoparticles can be used as contrast agents), and single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs, with its intrinsic Raman signal). The superb multiplexing capability of SERS-based Raman imaging can be extremely powerful in future research where different agents can be attached to different Raman tags to enable the interrogation of multiple biological events simultaneously in living subjects. The primary limitations of Raman imaging in humans are those also faced by other optical techniques, in particular limited tissue penetration. Over the last several years, Raman spectroscopy imaging has advanced significantly and many critical proof-of-principle experiments have been successfully carried out. It is expected that imaging with Raman Spectroscopy will continue to be a dynamic research field over the next decade.

Keywords: Raman Spectroscopy, Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering (CARS), Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), Single-walled carbon nanotube (SWNT), Molecular imaging, Nanoparticle

INTRODUCTION

Raman scattering, the inelastic scattering of a photon, occurs when a small fraction of the scattered light (approximately 1 in 107) is scattered by an excitation which leads to scattered photons with a frequency different from that of the incident photon [1]. There are two types of Raman scattering when energy exchange occurs between the incident photon and a molecule: Stokes scattering (the molecule absorbs energy) and anti-Stokes scattering (the molecule loses energy). Since the energy levels are unique for every molecule and the frequency of light scattered from a molecule is based on the structural characteristics of the chemical bonds, Raman spectrum is highly chemical specific. Therefore, Raman spectroscopy has been utilized as an important analytical tool in many research disciplines such as chemistry [1,2], medicine [3,4], physics [5], and material science [6].

Recently, Raman spectroscopy has also been explored for biomedical applications because it can provide detailed information on the chemical composition of cells and tissues. The Raman spectrum of a cell, a biochemical “fingerprint” containing molecular-level information about all the biopolymers inside the cell without the need of an exogenous label, can be used to characterize the distribution of multiple cellular components and study the dynamics of sub-cellular reactions with excellent spatial resolution [7,8]. Raman spectroscopy has showed tremendous promise for the analysis of biological processes within living cells, such as cell cycle dynamics, cell differentiation, and cell death [9]. Many diseases can lead to changes in molecular composition of the affected tissues. Raman spectroscopy can reflect these changes in many cases, thereby providing the physician with invaluable information for diagnosing certain diseases in real time. Over the last decade, the diagnostic potential of Raman spectroscopy has been demonstrated in cancers of various organs including the esophagus [10], breast [11,12], lung [13], bladder [14], skin [15-17], among others. Further, Raman spectroscopy has also been demonstrated useful for the diagnosis of certain vascular diseases such as vulnerable plaque detection in atherosclerosis [18].

Molecular imaging, “the visualization, characterization and measurement of biological processes at the molecular and cellular levels in humans and other living systems”, has gained enormous interest over the last decade [19]. Molecular imaging techniques typically include molecular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), optical bioluminescence, optical fluorescence, targeted ultrasound, single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and positron emission tomography (PET) [20,21]. Continued development and wider availability of scanners dedicated to small animal imaging studies, which can provide a similar in vivo imaging capability in mice, primates, and humans, can enable smooth transfer of knowledge and molecular measurements between species thereby facilitating clinical translation of novel imaging agents and/or techniques.

Among all these imaging techniques, no single modality is perfect and each has its advantages and disadvantages. The fact that Raman spectroscopy can provide molecular/chemical information of the tissue of interest makes it a competitive contender in the molecular imaging arena. Aside from chemical specificity, Raman spectroscopy also possesses many other desirable properties for imaging applications, such as high spatial resolution, superb multiplexing capability [22], low background signal, and excellent photostability [23]. However, the magnitude of Raman scattering is inherently weak (1 inelastically-scattered photon in every 107elastically scattered photons) which significantly hampers its biomedical applications. Over the years, several variations of Raman spectroscopy have been developed to enhance its sensitivity and many in vivo imaging studies with Raman spectroscopy have been successfully achieved [24-26]. This review article will provide a brief summary of Raman spectroscopy imaging, which includes the use of coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy (CARS), surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), and single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs).

IMAGING WITH CARS

CARS, a label-free imaging technique, employs multiple photons to address the molecular vibrations and produces a signal where the emitted waves are coherent with one another [27]. A non-linear process gives rise to a coherent radiation that is greatly enhanced when the frequency difference between the two laser pulses equals the Raman frequency of the chemical bond of interest. Although CARS is several orders of magnitude stronger than spontaneous Raman scattering, the absolute sensitivity of CARS is still relatively low. Therefore, CARS has primarily been used to detect molecules that are abundant in biological tissues, in particular lipids that have high density of CH2 groups [28].

CARS has been employed to image intracellular organelle transport in live cells [29]. Quantitative imaging of intracellular lipid droplets has also been achieved to characterize the interaction between cells and free lipids [30]. In addition, CARS can be used to differentiate embryonic stem cells from other cells within a growing culture [31]. The non-linear nature of CARS permitted imaging with sub-cellular resolution, thereby offering a means by which the chemical changes accompanying the early stages of stem cell differentiation can potentially be associated with certain intracellular compartments (e.g. the nucleus, cytoplasm, and membranes).

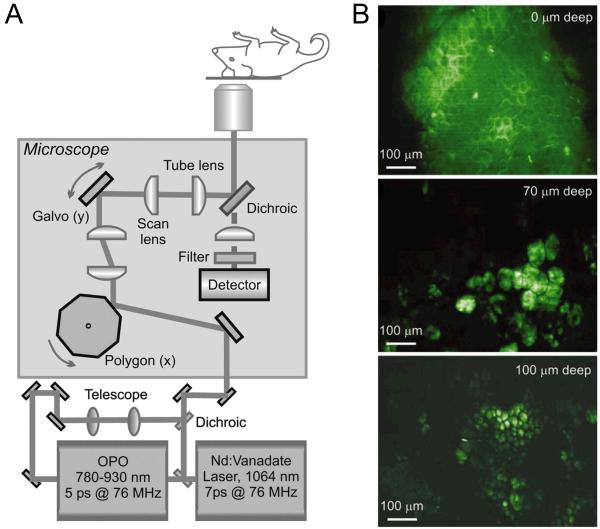

In one pioneering study, a sensitive technique for vibrational imaging of tissues by combining CARS with video-rate microscopy was developed [32]. Backscattering of the intense forward-propagating CARS radiation in tissues resulted in a strong epi-CARS signal, which allowed for real-time monitoring of dynamic processes such as the diffusion of chemical compounds in tissues. Focusing on the CH2 stretching vibrational band, CARS imaging and spectroscopy of lipid-rich tissue (e.g. the ear) in a live mouse was achieved with excellent contrast and sub-cellular resolution (Fig. (1)). Subsequently, in vivo imaging of myelin fibers in the mouse brain by CARS microscopy was reported [33]. Several studies have also demonstrated high resolution imaging of biological tissue samples with CARS [34], which may augment the diagnostic accuracy of traditional frozen section histopathology in needle biopsy, as well as dynamically define the margins of tumor resection during surgery.

Fig. (1).

In vivo imaging with CARS. A. Schematic of a real-time CARS imaging microscope. OPO: optical parametric oscillator. B. Images of a hairless mouse ear at different depth. The Raman shift is set at 2,845 cm−1 to address the lipid CH2 symmetric stretch vibration. Top: the stratum corneum; middle: adipocytes of the dermis; bottom: adipocytes of the subcutaneous layer. Adapted from [32].

Although imaging with CARS is still at its infancy, proof-of-principle in vivo imaging has been demonstrated. In addition to the C-H bond, CARS microscopy may also be used with other vibrational modes (e.g. O-H stretching). Advances in several areas, such as miniaturization of the microscope objective, high-speed scanning, and longer wavelength excitation, are expected to significantly facilitate CARS imaging of live animals in the future [28]. The recent development of CARS endoscopy may also enable in situ chemically selective imaging for various biomedical applications [35].

IMAGING WITH SERS

Besides the label-free CARS technique, imaging with SERS has also gained significant interest over the last several years [24]. SERS is a plasmonic effect where the molecules adsorbed on a rough metal surface can result in high Raman scattering intensities by increasing in the incident electric field [36]. Typically, metal nanoparticles (e.g. gold) with various fluorescent dyes (such as Cy3, Cy5, and rhodamine) are used for SERS-based applications [37]. For detailed mechanism of SERS and the design of SERS nanoparticles, interested readers are referred to several excellent recent review articles on this topic [24,26]. The SERS effect can increase the Raman signal intensity by up to 1014-1015 fold, resulting in a detection sensitivity comparable to fluorescence [38].

In Vitro Applications of SERS

One major class of materials used for SERS applications is gold/silver nanoparticles [39,40]. In a pioneering report, gold nanoparticles (~13 nm in diameter) modified with Cy3-labeled, alkylthiol-capped oligonucleotide strands were used as probes to monitor the presence of specific target DNA strands [41]. The Cy3 dye was chosen as the Raman label because of its large Raman cross-section. In another study, Raman spectra and Raman images were recorded for methylene blue molecules adsorbed as a single layer on gold nanoparticles in periodic arrays [42]. It was suggested that all excited nanoparticles contribute equally to the Raman signal which makes SERS a useful technique for studying the plasmon properties. Recently, gold nanoparticles conjugated with a nuclear localization signal peptide were reported to enter the Hela cell nucleus, thus revealing spatially localized chemical information of the nucleus based on the SERS effect [43]. Importantly, this multifunctional nanoparticle which is capable of sub-cellular targeting, intracellular imaging, and real-time SERS detection was also found to be non-toxic and biocompatible. In another report, PEGylated gold nanoparticles encapsulating a Raman reporter dye have been used as Raman tags for tumor cell biomarker detection [44].

Due to the fact that Raman spectral lines are narrower (~1 nm) than fluorescence signals, SERS nanoparticles can be attractive candidates for multiplexed immunostaining. In one study, antibody-conjugated SERS nanoparticles have been evaluated for immunostaining of the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in tissue slices obtained from prostate cancer patients [45]. Although it was found that these SERS nanoparticles had lower staining accuracy than their fluorescent counterparts, they did provide comparable signal intensities to common fluorescent dyes and good reproducibility/consistency.

Gold nanorods can also exhibit strong SERS effect which makes them suitable optical sensors for biological and medical applications [46]. For example, peptide-conjugated gold nanorods were investigated for nuclear targeting of various cell types and Raman imaging [47]. When conjugated with a nuclear localization signal peptide and incubated with cells, the gold nanorods were detected in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus by Raman scattering. More importantly, the Raman spectra were different between the benign and cancer cell lines which could potentially be used for diagnostic applications. Antibody-conjugated gold nanorods have been applied for oral cancer detection [48]. When conjugated with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (anti-EGFR) antibodies, these gold nanorods were shown to exhibit strong Rayleigh (Mie) scattering that can allow for Raman imaging. Molecules near the gold nanorods in the cancer cells exhibited Raman spectra that were greatly enhanced, sharp, and polarized which may serve as diagnostic signatures for cancer cells.

Silver nanoparticle-embedded silica spheres with organic Raman labels (termed “SERS dots”) were developed for cancer cell targeting, upon conjugation with antibodies [49]. Raman signal intensity of these SERS dots exhibits a linear correlation with the quantity, which can enable accurate target quantification. Subsequently, similar SERS dots were further modified with fluorescent organic dyes and antibodies for multiplexed targeting, tracking, and imaging of apoptosis [50]. It was reported that these “F-SERS dots” could be used to monitor apoptosis effectively and simultaneously through fluorescence as well as Raman signals in both cells and tissues with high selectivity.

Recently, isocyanide-functionalized silver and gold nanoparticles were investigated in cells with SERS [51]. The SERS marker band at approximately 2,100 cm−1 was used to determine the location of the nanoparticles inside the cell, without much spectral interference from other cellular components, which makes these nanoparticles potentially useful for imaging certain biological processes at the single cell level. In another study, rhodamine B isothiocyanate-modified, silver-deposited silica or polystyrene beads were reported to be capable of detecting streptavidin down to a concentration of 10−13M based on the SERS signal [52].

In Vivo Imaging with SERS

Non-invasive SERS-based imaging has been achieved in animal models. In one pioneering report, it was shown that small molecule Raman reporters (such as fluorescent dyes) on the surface of gold nanoparticles were stabilized by thiolated PEG and gave large optical enhancements [53]. These PEGylated SERS nanoparticles, with light emission in the near-infrared window (700-900 nm), were found to be considerably brighter than semiconductor quantum dots (common nanoparticles used for fluorescence imaging [21,54,55]. When conjugated to tumor-targeting ligands, these SERS nanoparticles could home to tumor markers (such as EGFR [56]) on human cancer cells and in xenograft tumor models. Interestingly, although Raman spectra of the SERS nanoparticles were reported, a Raman image was not reported for the tumor-bearing mice.

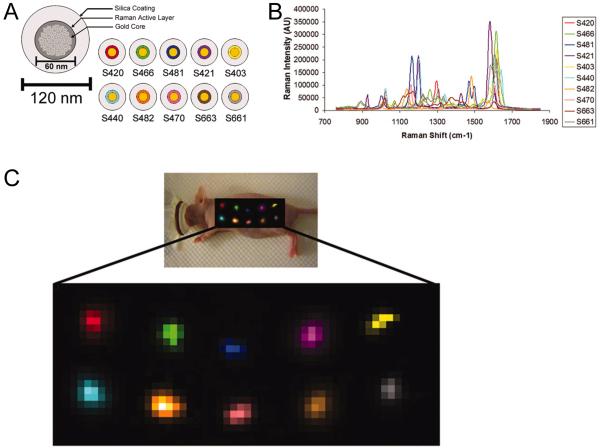

In another study, SERS nanoparticles composed of a gold core, a Raman-active molecular layer, and a silica coating were used for Raman imaging in vivo [22]. A minimum detection sensitivity of 8 picomolar of SERS nanoparticles was observed in a living mouse. As a proof-of-principle, in vivo multiplexed imaging of four different SERS nanoparticles was demonstrated. In a follow-up study, the superb multiplexing capability of Raman spectroscopy was further explored [57]. Spectral fingerprints of 10 different SERS nanoparticles were successfully separated after subcutaneous injection into a living mouse (Fig. (2)). The five most intense and spectrally unique SERS nanoparticles were selected and intravenously injected to image their natural accumulation in the liver (most nanoparticles will accumulate in the liver when intravenously injected due to the reticuloendothelial system uptake [21,58]), which were also all identified and spectrally separated by the Raman imaging system. More importantly, linear correlation of the Raman signal with SERS nanoparticle concentration was observed for both subcutaneous and intravenous injection, which sets the foundation for future quantitative, targeted, and multiplexed Raman imaging in vivo.

Fig. (2).

Multiplexed Raman imaging in vivo. A. Schematic of a SERS nanoparticle consisting of a gold core, a Raman active layer, and glass coating. Ten different SERS nanoparticles were used. B. Raman spectra of the 10 SERS nanoparticles, each assigned a different color. C. Multiplexed Raman imaging of 10 different SERS nanoparticles in vivo. The particles were injected subcutaneously into a nude mouse and the post-processing software separated all 10 SERS nanoparticles into their respective channels with minimal crosstalk. Top: S420, S466, S481, S421, and S403. Bottom: S440, S482, S470, S663, and S661. Adapted from [57].

Recently, a gold nanotag was synthesized to combine multi-colored Raman spectroscopy with x-ray computed tomography (CT) [59]. Different nanotags were prepared with quasi-spherical gold nanoparticles encoded with various reporter dyes, each possessing a unique Raman spectrum. A library of these nanotags with six different Raman colors were constructed with good SERS signal intensity and x-ray attenuation, higher than the iodinated CT contrast agents used in the clinic. Proof-of-principle in vivo imaging studies with both SERS and CT successfully demonstrated the dual-modality imaging capability of these nanotags.

RAMAN SPECTROSCOPY WITH SWNTS

SWNT has an intense Raman peak at 1593 cm−1 (the G band), produced by the strong electron-photon coupling which can cause efficient excitation of tangential vibration upon light exposure [60]. The narrow Raman peak of SWNTs, easily differentiated from the autofluorescence background, has been used to study the biodistribution of functionalized SWNTs in mice [61,62]. Unlike SERS nanoparticles, SWNTs are inherently Raman active and do not need a metal surface enhancer to improve their Raman detection, which is highly desirable for biological applications. Further, the Raman excitation and scattering photons of SWNTs are both in the near-infrared region, the most transparent optical window for in vivo imaging.

Raman spectroscopy with SWNTs has recently been comprehensively reviewed [63]. Therefore, we will only provide a brief summary of this topic in this article. A laser-scanning optical microscope, which can allow for highly repeatable imaging over large sample areas, was developed to measure the low-temperature Raman scattering spectra of individual SWNTs [64]. Anodized aluminum oxide perforated in an organized fashion has been employed to investigate the SERS effect of SWNTs at micron length and a large signal enhancement was observed [65]. SWNTs have also been investigated in vitro with a variety of other Raman imaging techniques such as near-field Raman imaging/spectroscopy [66-68], Raman mapping and 3D real optical imaging [69], and confocal Raman imaging [70,71].

In one of the abovementioned reports, tumor targeting of peptide-conjugated SWNTs in living mice was non-invasively evaluated with Raman spectroscopy [22]. Subsequently, an optimized Raman microscope was employed to further investigate the in vivo tumor targeting and localization of SWNTs in mice [72]. The molecular target and targeting ligand used in these studies was integrin αvβ3 and an Arginine-Glycine-Aspartic acid (RGD, potent integrin αvβ3 antagonist [73]) peptide respectively, one of the most extensively studied and validated receptor-ligand pair over the last decade [74,75]. Raman imaging commenced over three days revealed more accumulation of SWNT-RGD in the U87MG human glioblastoma tumor (integrin αvβ3-positive [76,77]) than the unconjugated SWNTs (Fig. (3A)) [72]. These reports strongly supported further development of non-invasive Raman imaging as a tool to assess the efficacy of new diagnostic strategies and therapies in small animal models, which may eventually lead to improvements in cancer patient care.

Fig. (3).

Raman imaging with SWNTs. A. Left: photograph of an integrin αvβ3-positive tumor-bearing mouse depicting tumor area scanned with Raman spectroscopy (black box). Right: Raman tumor maps of mice receiving SWNT-RGD conjugate or unconjugated SWNT at 72 h post-injection. B. Deconvoluted confocal Raman spectroscopy images of a mixture of three cell lines after incubation with a mixture of three different, molecularly targeted SWNT conjugates. Each of the SWNT conjugate has a different Raman signature (due to different carbon isotope composition) and was conjugated with a targeting moiety for a different molecular target. Adapted from [72,78].

Recently, multiplexed Raman imaging of live cells with isotopically modified SWNTs was reported [78]. SWNTs with different isotope (12C and/or 13C) compositions, which in turn exhibit distinct Raman G-band peaks, were investigated in this study where different cancer cells over-expressing different cell surface receptors were used for receptor-specific targeting. Three differently “colored” SWNTs were each conjugated with a different targeting ligand, each recognizing one specific receptor, which allowed for multicolor Raman imaging of cells in a multiplexed manner (Fig. (3B)). In another report, antibody-functionalized SWNTs were used as multicolor Raman labels for highly sensitive, multiplexed protein detection in an arrayed format [79]. When combined with SERS substrates, the strong Raman intensity of SWNTs afforded protein detection sensitivity in sandwich assays down to the femtomolar level. By conjugating different antibodies to pure 12C- and 13C-SWNTs, multiplexed Raman detection of different proteins was demonstrated. Besides the use of SWNTs with different isotope compositions, SWNTs with controlled diameters (which exhibit distinctive Raman peaks in the radial-breathing mode depending on the diameter [80]) may also be applied for multicolor Raman sensing/imaging in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

A variety of contrast agents, both endogenous (e.g. lipids) and exogenous (e.g. SERS nanoparticles and SWNTs), have been investigated for imaging with Raman spectroscopy. Since most imaging modalities do not offer single cell resolution, in vivo CARS imaging will fill an important niche for studying certain disease processes (especially those that involve lipids). The key advantage of SERS-based Raman imaging over fluorescence imaging (the most widely used optical imaging technique) is the superb multiplexing capability, good quantitation, and lack of confounding background signal from autofluorescence. In particular, multiplexed imaging can be extremely powerful in future research where different agents can be attached to different Raman tags to enable the interrogation of multiple biological events simultaneously in living subjects. For better performance in vivo, future generations of smaller SERS nanoparticles will be needed since the currently used SERS nanoparticles are typically around 100 nm in diameter which can lead to significant uptake in the reticuloendothelial system (e.g. the liver and spleen). Aside from Raman imaging, SWNTs can also be used for a variety of other applications such as drug/gene delivery, sensing, photothermal therapy, as well as multimodality imaging which takes advantage of both its intrinsic signal and versatile chemistry [63,81]. Combination of these applications with Raman imaging can be a fertile area of research and it is expected that SWNT-based investigations will continue to be an active field over the next decade.

The primary limitations of Raman imaging in humans are those also faced by other optical techniques. Even in the near-infrared region, light penetration beyond a few centimeters of tissue is quite difficult. In clinical settings, optical imaging (including Raman spectroscopy) is only relevant for tissues close to the surface of the skin (for example, breast imaging), tissues accessible by endoscopy (such as the esophagus and colon), and intraoperative visualization (typically image-guided surgery). Much future improvement in both the imaging system and contrast agents will be needed before Raman imaging can become a clinical reality.

Since no single imaging modality can have all the desirable features such as high sensitivity, good spatial/temporal resolution, multiplexing capacity, low cost, and high-throughput, combination of Raman imaging with other techniques such as fluorescence, photoacoustic [82], or PET imaging is a fertile area for future research. For personalized patient management, ex vivo sensing and in vivo imaging are both important. Raman-based sensing (using blood samples drawn before, during, and after treatment) in combination with in vivo diagnostics (non-invasive imaging before, during, and after treatment) may provide a synergistic approach in predicting which patients will likely respond to a specific molecular therapy and monitor their responses to personalized therapy. Over the last several years, Raman spectroscopy imaging has advanced significantly and many critical proof-of-principle experiments have been successfully carried out. The next decade will likely witness rapid expansion of this unique imaging technique.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors acknowledge financial support from the UW School of Medicine and Public Health’s Medical Education and Research Committee through the Wisconsin Partnership Program, the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center, NCRR 1UL1RR025011, and a Susan G. Komen Postdoctoral Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- [1].Schaeberle MD, Kalasinsky VF, Luke JL, Lewis EN, Levin IW, Treado PJ. Raman chemical imaging: histopathology of inclusions in human breast tissue. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:1829–1833. doi: 10.1021/ac951245a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wetzel DL, LeVine SM. Imaging molecular chemistry with infrared microscopy. Science. 1999;285:1224–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ling J, Weitman SD, Miller MA, Moore RV, Bovik AC. Direct Raman imaging techniques for study of the subcellular distribution of a drug. Appl. Opt. 2002;41:6006–6017. doi: 10.1364/ao.41.006006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Djaker N, Marguet D, Rigneault H. Stimulated Raman microscopy (CARS): From principles to applications. Med. Sci. (Paris) 2006;22:853–858. doi: 10.1051/medsci/20062210853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Moerner WE, Orrit M. Illuminating single molecules in condensed matter. Science. 1999;283:1670–1676. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kawata S, Inouye Y, Ichimura T. Near-field optics and spectroscopy for molecular nano-imaging. Sci. Prog. 2004;87:25–49. doi: 10.3184/003685004783238580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chan JW, Taylor DS, Zwerdling T, Lane SM, Ihara K, Huser T. Micro-Raman spectroscopy detects individual neoplastic and normal hematopoietic cells. Biophys. J. 2006;90:648–656. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.066761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chan JW, Taylor DS, Lane SM, Zwerdling T, Tuscano J, Huser T. Nondestructive identification of individual leukemia cells by laser trapping Raman spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:2180–2187. doi: 10.1021/ac7022348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Swain RJ, Stevens MM. Raman microspectroscopy for non-invasive biochemical analysis of single cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007;35:544–549. doi: 10.1042/BST0350544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bohorfoush AG. New diagnostic methods for esophageal carcinoma. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2000;155:55–62. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59600-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Haka AS, Shafer-Peltier KE, Fitzmaurice M, Crowe J, Dasari RR, Feld MS. Diagnosing breast cancer by using Raman spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:12371–12376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501390102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Haka AS, Volynskaya Z, Gardecki JA, Nazemi J, Lyons J, Hicks D, Fitzmaurice M, Dasari RR, Crowe JP, Feld MS. In vivo margin assessment during partial mastectomy breast surgery using raman spectroscopy. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3317–3322. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Huang Z, McWilliams A, Lui H, McLean DI, Lam S, Zeng H. Near-infrared Raman spectroscopy for optical diagnosis of lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2003;107:1047–1052. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].de Jong BWD, Bakker Schut TC, Maquelin K, van der Kwast T, Bangma CH, Kok D-J, Puppels GJ. Discrimination between nontumor bladder tissue and tumor by Raman spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:7761–7769. doi: 10.1021/ac061417b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Caspers PJ, Lucassen GW, Puppels GJ. Combined in vivo confocal Raman spectroscopy and confocal microscopy of human skin. Biophys. J. 2003;85:572–580. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74501-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jhan JW, Chang WT, Chen HC, Wu MF, Lee YT, Chen CH, Liau I. Integrated multiple multi-photon imaging and Raman spectroscopy for characterizing structure-constituent correlation of tissues. Opt. Express. 2008;16:16431–16441. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.016431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nijssen A, Maquelin K, Santos LF, Caspers PJ, Bakker Schut TC, den Hollander JC, Neumann MH, Puppels GJ. Discriminating basal cell carcinoma from perilesional skin using high wave-number Raman spectroscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2007;12:034004. doi: 10.1117/1.2750287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Motz JT, Fitzmaurice M, Miller A, Gandhi SJ, Haka AS, Galindo LH, Dasari RR, Kramer JR, Feld MS. In vivo Raman spectral pathology of human atherosclerosis and vulnerable plaque. J. Biomed. Opt. 2006;11:021003. doi: 10.1117/1.2190967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mankoff DA. A Definition of Molecular Imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2007;48:18N–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Massoud TF, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging in living subjects: seeing fundamental biological processes in a new light. Genes Dev. 2003;17:545–580. doi: 10.1101/gad.1047403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cai W, Chen X. Nanoplatforms for Targeted Molecular Imaging in Living Subjects. Small. 2007;3:1840–1854. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Keren S, Zavaleta C, Cheng Z, de la Zerda A, Gheysens O, Gambhir SS. Noninvasive molecular imaging of small living subjects using Raman spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:5844–5849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710575105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ryder AG. Surface enhanced Raman scattering for narcotic detection and applications to chemical biology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2005;9:489–493. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Qian XM, Nie SM. Single-molecule and single-nanoparticle SERS: from fundamental mechanisms to biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:912–920. doi: 10.1039/b708839f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wachsmann-Hogiu S, Weeks T, Huser T. Chemical analysis in vivo and in vitro by Raman spectroscopy--from single cells to humans. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2009;20:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Schlucker S. SERS microscopy: nanoparticle probes and biomedical applications. Chemphyschem. 2009;10:1344–1354. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rodriguez LG, Lockett SJ, Holtom GR. Coherent anti-stokes Raman scattering microscopy: a biological review. Cytometry A. 2006;69:779–791. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wang HW, Fu Y, Huff TB, Le TT, Wang H, Cheng JX. Chasing lipids in health and diseases by coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. Vib. Spectrosc. 2009;50:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.vibspec.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nan X, Potma EO, Xie XS. Nonperturbative chemical imaging of organelle transport in living cells with coherent anti-stokes Raman scattering microscopy. Biophys. J. 2006;91:728–735. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.074534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Rinia HA, Burger KN, Bonn M, Muller M. Quantitative label-free imaging of lipid composition and packing of individual cellular lipid droplets using multiplex CARS microscopy. Biophys. J. 2008;95:4908–4914. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.137737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Konorov SO, Glover CH, Piret JM, Bryan J, Schulze HG, Blades MW, Turner RF. In situ analysis of living embryonic stem cells by coherent anti-stokes Raman microscopy. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:7221–7225. doi: 10.1021/ac070544k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Evans CL, Potma EO, Puoris’haag M, Cote D, Lin CP, Xie XS. Chemical imaging of tissue in vivo with video-rate coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16807–16812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508282102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fu Y, Huff TB, Wang HW, Wang H, Cheng JX. Ex vivo and in vivo imaging of myelin fibers in mouse brain by coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy. Opt. Express. 2008;16:19396–19409. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.019396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Evans CL, Xu X, Kesari S, Xie XS, Wong ST, Young GS. Chemically-selective imaging of brain structures with CARS microscopy. Opt. Express. 2007;15:12076–12087. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.012076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Legare F, Evans CL, Ganikhanov F, Xie XS. Towards CARS endoscopy. Opt. Express. 2006;14:4427–4432. doi: 10.1364/oe.14.004427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fleischmann M, Hendra PJ, McQuillan AJ. Raman spectra of pyridine adsorbed at a silver electrode. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1974;26:163–166. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Han XX, Zhao B, Ozaki Y. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering for protein detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009;394:1719–1727. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-2702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nie S, Emory SR. Probing single molecules and single nanoparticles by surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Science. 1997;275:1102–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kneipp J, Kneipp H, Wittig B, Kneipp K. Novel optical nanosensors for probing and imaging live cells. Nanomedicine. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.07.009. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Xie J, Zhang Q, Lee JY, Wang DI. The synthesis of SERS-active gold nanoflower tags for in vivo applications. ACS Nano. 2008;2:2473–2480. doi: 10.1021/nn800442q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cao YC, Jin R, Mirkin CA. Nanoparticles with Raman spectroscopic fingerprints for DNA and RNA detection. Science. 2002;297:1536–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5586.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Laurent G, Felidj N, Truong SL, Aubard J, Levi G, Krenn JR, Hohenau A, Leitner A, Aussenegg FR. Imaging surface plasmon of gold nanoparticle arrays by far-field Raman scattering. Nano Lett. 2005;5:253–258. doi: 10.1021/nl048234u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Xie W, Wang L, Zhang Y, Su L, Shen A, Tan J, Hu J. Nuclear targeted nanoprobe for single living cell detection by surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Bioconjug. Chem. 2009;20:768–773. doi: 10.1021/bc800469g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Nyagilo J, Xiao M, Sun X, Dave DP. Multi-color raman nanotags for tumor cell biomarker detection. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2009;1:6314–6317. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5332780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lutz B, Dentinger C, Sun L, Nguyen L, Zhang J, Chmura A, Allen A, Chan S, Knudsen B. Raman nanoparticle probes for antibody-based protein detection in tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2008;56:371–379. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7313.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hirsch LR, Gobin AM, Lowery AR, Tam F, Drezek RA, Halas NJ, West JL. Metal nanoshells. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2006;34:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-9001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Oyelere AK, Chen PC, Huang X, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed MA. Peptide-conjugated gold nanorods for nuclear targeting. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007;18:1490–1497. doi: 10.1021/bc070132i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Huang X, El-Sayed IH, Qian W, El-Sayed MA. Cancer cells assemble and align gold nanorods conjugated to antibodies to produce highly enhanced, sharp, and polarized surface Raman spectra: a potential cancer diagnostic marker. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1591–1597. doi: 10.1021/nl070472c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kim JH, Kim JS, Choi H, Lee SM, Jun BH, Yu KN, Kuk E, Kim YK, Jeong DH, Cho MH, Lee YS. Nanoparticle probes with surface enhanced Raman spectroscopic tags for cellular cancer targeting. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:6967–6973. doi: 10.1021/ac0607663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yu KN, Lee SM, Han JY, Park H, Woo MA, Noh MS, Hwang SK, Kwon JT, Jin H, Kim YK, Hergenrother PJ, Jeong DH, Lee YS, Cho MH. Multiplex targeting, tracking, and imaging of apoptosis by fluorescent surface enhanced Raman spectroscopic dots. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007;18:1155–1162. doi: 10.1021/bc070011i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Lee SY, Jang SH, Cho MH, Kim YM, Cho KC, Ryu PD, Gong MS, Joo SW. In situ single cell monitoring by isocyanide-functionalized Ag and Au nanoprobe-based Raman spectroscopy. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009;19:904–910. doi: 10.4014/jmb.0901.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kim K, Lee HB, Lee YM, Shin KS. Rhodamine B isothiocyanate-modified Ag nanoaggregates on dielectric beads: a novel surface-enhanced Raman scattering and fluorescent imaging material. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009;24:1864–1869. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Qian X, Peng XH, Ansari DO, Yin-Goen Q, Chen GZ, Shin DM, Yang L, Young AN, Wang MD, Nie S. In vivo tumor targeting and spectroscopic detection with surface-enhanced Raman nanoparticle tags. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Cai W, Hsu AR, Li ZB, Chen X. Are quantum dots ready for in vivo imaging in human subjects? Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2007;2:265–281. doi: 10.1007/s11671-007-9061-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Li ZB, Cai W, Chen X. Semiconductor quantum dots for in vivo imaging. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2007;7:2567–2581. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2007.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Cai W, Niu G, Chen X. Multimodality imaging of the HER-kinase axis in cancer. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2008;35:186–208. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0560-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Zavaleta CL, Smith BR, Walton I, Doering W, Davis G, Shojaei B, Natan MJ, Gambhir SS. Multiplexed imaging of surface enhanced Raman scattering nanotags in living mice using noninvasive Raman spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:13511–13516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813327106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hong H, Zhang Y, Sun J, Cai W. Molecular imaging and therapy of cancer with radiolabeled nanoparticles. Nano Today. 2009;4:399–413. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Xiao M, Nyagilo J, Arora V, Kulkarni P, Xu D, Sun X, Dave DP. Gold nanotags for combined multi-colored Raman spectroscopy and x-ray computed tomography. Nanotechnology. 21:035101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/3/035101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Jorio A, Saito R, Dresselhaus G, Dresselhaus MS. Determination of nanotubes properties by Raman spectroscopy. Philos. Transact. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2004;362:2311–2336. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2004.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Liu Z, Cai W, He L, Nakayama N, Chen K, Sun X, Chen X, Dai H. In vivo biodistribution and highly efficient tumour targeting of carbon nanotubes in mice. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007;2:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Liu Z, Davis C, Cai W, He L, Chen X, Dai H. Circulation and long-term fate of functionalized, biocompatible single-walled carbon nanotubes in mice probed by Raman spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:1410–1415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707654105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Hong H, Gao T, Cai W. Molecular imaging with single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Today. 2009;4:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Zhang L, Aite S, Yu Z. Unique laser-scanning optical microscope for low-temperature imaging and spectroscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2007;78:083701. doi: 10.1063/1.2768924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Zhang C, Abdijalilov K, Grebel H. Surface enhanced Raman with anodized aluminum oxide films. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;127:044701. doi: 10.1063/1.2752498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Anderson N, Hartschuh A, Cronin S, Novotny L. Nanoscale vibrational analysis of single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2533–2537. doi: 10.1021/ja045190i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Hartschuh A, Qian H, Meixner AJ, Anderson N, Novotny L. Nanoscale optical imaging of excitons in single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2310–2313. doi: 10.1021/nl051775e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Hartschuh A, Sanchez EJ, Xie XS, Novotny L. High-resolution near-field Raman microscopy of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;90:095503. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.095503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Atalay H, Lefrant S. Analysing one isolated single walled carbon nanotube in the near-field domain with selective nanovolume Raman spectroscopy. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2004;4:749–761. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2004.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Doorn SK, Zheng L, O’Connell M,J, Zhu Y, Huang S, Liu J. Raman spectroscopy and imaging of ultralong carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:3751–3758. doi: 10.1021/jp0463159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Itkis ME, Perea DE, Jung R, Niyogi S, Haddon RC. Comparison of analytical techniques for purity evaluation of single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:3439–3448. doi: 10.1021/ja043061w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Zavaleta C, de la Zerda A, Liu Z, Keren S, Cheng Z, Schipper M, Chen X, Dai H, Gambhir SS. Noninvasive Raman spectroscopy in living mice for evaluation of tumor targeting with carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2800–2805. doi: 10.1021/nl801362a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Cai W, Chen X. Anti-angiogenic cancer therapy based on integrin αvβ3antagonism. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2006;6:407–428. doi: 10.2174/187152006778226530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Cai W, Chen X. Multimodality molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis. J. Nucl. Med. 2008;49(Suppl 2):113S–128S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Cai W, Niu G, Chen X. Imaging of integrins as biomarkers for tumor angiogenesis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008;14:2943–2973. doi: 10.2174/138161208786404308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Cai W, Chen K, Li ZB, Gambhir SS, Chen X. Dual-function probe for PET and near-infrared fluorescence imaging of tumor vasculature. J. Nucl. Med. 2007;48:1862–1870. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.043216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Cai W, Wu Y, Chen K, Cao Q, Tice DA, Chen X. In vitro and in vivo characterization of 64Cu-labeled Abegrin™, a humanized monoclonal antibody against integrin αvβ3. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9673–9681. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Liu Z, Li X, Tabakman SM, Jiang K, Fan S, Dai H. Multiplexed multicolor Raman imaging of live cells with isotopically modified single walled carbon nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13540–13541. doi: 10.1021/ja806242t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Chen Z, Tabakman SM, Goodwin AP, Kattah MG, Daranciang D, Wang X, Zhang G, Li X, Liu Z, Utz PJ, Jiang K, Fan S, Dai H. Protein microarrays with carbon nanotubes as multicolor Raman labels. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1285–1292. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Rao AM, Richter E, Bandow S, Chase B, Eklund PC, Williams KA, Fang S, Subbaswamy KR, Menon M, Thess A, Smalley RE, Dresselhaus G, Dresselhaus MS. Diameter-selective Raman scattering from vibrational modes in carbon nanotubes. Science. 1997;275:187–191. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Liu Z, Tabakman S, Welsher K, Dai H. Carbon Nanotubes in Biology and Medicine: In vitro and in vivo Detection, Imaging and Drug Delivery. Nano Res. 2009;2:85–120. doi: 10.1007/s12274-009-9009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].De la Zerda A, Zavaleta C, Keren S, Vaithilingam S, Bodapati S, Liu Z, Levi J, Smith BR, Ma TJ, Oralkan O, Cheng Z, Chen X, Dai H, Khuri-Yakub BT, Gambhir SS. Carbon nanotubes as photoacoustic molecular imaging agents in living mice. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008;3:557–562. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]