Abstract

Background

International medical graduates (IMGs) comprise approximately 25% of the US physician workforce, with significant representation in primary care and care of vulnerable populations. Despite the central role of IMGs in the US healthcare system, understanding of their professional experiences is limited.

Objective

To characterize the professional experiences of non-US born IMGs from limited-resource nations practicing primary care in the US.

Design

Qualitative study based on in-depth in-person interviews.

Participants

Purposeful sample of IMGs (n = 25) diverse in country of origin, length of practice in the US, specialty (internal medicine, family medicine and pediatrics), age and gender. Participants were currently practicing primary care physicians in New York, New Jersey or Connecticut.

Approach

A standardized interview guide was used to explore professional experiences of IMGs.

Key Results

Four recurrent and unifying themes characterize these experiences: 1) IMGs experience both overt and subtle forms of workplace bias and discrimination; 2) IMGs recognize professional limitations as part of “the deal”; 3) IMGs describe challenges in the transition to the culture and practice of medicine in the US; 4) IMGs bring unique skills and advantages to the workplace.

Conclusions

Our data reveal that IMGs face workplace challenges throughout their careers. Despite diversity in professional background and demographic characteristics, IMGs in our study reported common experiences in the transition to and practice of medicine in the US. Findings suggest that both workforce and workplace interventions are needed to enable IMG physicians to sustain their essential and growing role in the US healthcare system. Finally, commonalities with experiences of other minority groups within the US healthcare system suggest that optimizing IMGs’ experiences may also improve the experiences of an increasingly diverse healthcare workforce.

KEY WORDS: primary care, qualitative research, workforce, international medical graduates

INTRODUCTION

International medical graduates (IMGs), defined as physicians who did not attend medical school in the United States or Canada, comprise approximately 25% of the physician workforce in the United States.1 Nearly 90% of IMGs are non-US born, and over two-thirds are from low-resource, developing nations.1 IMGs are projected to comprise over 35% of the US primary care physician workforce in the coming years.2,3 They fill critical gaps in the US physician workforce, particularly in primary care,2–5 care for vulnerable populations,6 and in physician shortage areas.6,7

Despite the vital role of IMGs within the US healthcare system, understanding of their professional experiences is limited, though it is clear that elements of their experiences differ from those of the larger physician population. Prior empirical research has described IMG demographics and workforce trends and compared them to those of United States medical graduates (USMGs)8–11 while studies of job satisfaction indicate that regardless of field of specialty, IMGs are more likely than USMGs to report low career satisfaction.12–14

Research with IMGs during residency training identified challenges in the process of transition, including caring for patients across linguistic and cultural barriers.15

However, commonalities in the professional experiences of IMG physicians have not been described, and the effect of being an IMG on workplace interactions and career trajectories has not been systematically explored. Accordingly, we sought to characterize the experiences of non-US born IMGs, and focused on those from limited-resource, developing nations for whom differences in the culture, structures and practice of medicine are more likely to be substantial.

METHODS

We chose a qualitative method because this approach is optimal for exploring cultural and social interactions and complex, potentially sensitive topics.16,17

Study Design and Sampling

We conducted in-depth in-person interviews18 with an information-rich, purposeful sample17 of non-US born IMG physicians from limited-resource, developing nations, currently in outpatient primary care practice (family medicine, internal medicine and pediatrics). Residents in training were excluded. Limited resource, developing nations were defined as countries the World Health Organization has identified as having <2 physician per 1,000 individuals in the population.19

We identified potential participants through multiple sources: the American Medical Association’s IMG Section email listserv; web-based state licensure board databases for Connecticut, New York and New Jersey; and department chairs at regional institutions.

Recruitment and data collection were conducted until thematic saturation17 was achieved. One researcher (PC) reached 27 physicians via telephone to verbally invite their participation; two refused due to time constraints and family illness, respectively. The Human Investigation Committee at the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, CT approved the research protocol. All participants provided verbal informed consent.

Data Collection

One researcher (PC) conducted all in-person, in-depth interviews. The interviewer is a pediatrician by training, a second-generation immigrant and member of an ethnic minority group.

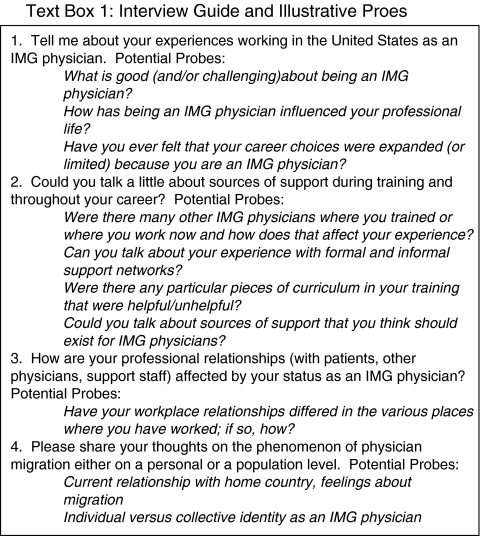

The interview guide (text box) consisted of open-ended, ‘grand tour’ questions18,20 beginning with: “Tell me about your experiences working as an International medical graduate physician in the United States.” Probes were used to encourage clarification and elaboration on participants’ statements.21 Probes are not standardized, and their use is highly contextual for each interview.17 Interviews were audio-taped, professionally transcribed and reviewed to ensure accuracy. Participants completed an anonymous demographic survey at the conclusion of the interview.

ANALYSIS

Data analysis was performed by a 6-person multidisciplinary team including a pediatrician, family physician, internists (including an IMG), an organizational psychologist, and a health services researcher, each with training and expertise in qualitative methods. We developed a code structure in stages and in accordance with principles of grounded theory,21 using systematic, inductive procedures to generate insights grounded in the views expressed by study participants.

First, the full research team independently coded three transcripts, meeting to negotiate consensus over differences in independent coding. We used the constant comparative method21 to insure that emergent themes were consistently classified, expand on existing codes, identify novel concepts and refine codes. Second, PC, SB and AG independently coded all remaining transcripts, met regularly to achieve consensus and finalized a comprehensive code structure capturing all data concepts. PC then systematically applied the final code structure to all transcripts. We used qualitative analysis software (ATLAS.ti 5.0, Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) to facilitate data organization and retrieval.

Finally, at several stages throughout the iterative process of data collection and analysis, we conducted participant confirmation16,17,22 in which summary results were distributed to participants to confirm that the themes being developed accurately reflected participants’ experience.

RESULTS

Demographics

Our final sample (Table 1) consisted of 25 IMG physicians, with a 93% participation rate. We achieved broad representation with regard to age, specialty, geographic regions of origin, and years of clinical experience in the US.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | Resulta |

|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 46 (30–65) |

| Female | 11 (44) |

| Specialty | |

| Family practice | 7 (28) |

| Pediatrics | 8 (32) |

| Internal medicine | 10 (40) |

| Region of origin | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 6 (24) |

| South Asia | 8 (32) |

| East Asia | 5 (20) |

| Latin America | 2 (8) |

| Middle East | 4 (16) |

| Years since completed residency | |

| 0–5 years | 5 (20) |

| 6–10 years | 6 (24) |

| 11–15 years | 7 (28) |

| 16–20 years | 3 (12) |

| 20–25 years | 1 (4) |

| >25 years | 3 (12) |

aResults are range (mean) for age and number (%) for all other variables

Themes

Our analysis generated insights into the perceptions and experiences of IMG physicians regarding a broad range of aspects of practicing medicine in the US. Our final code structure contained six primary codes, each with discrete sub-codes encompassing a broad range of IMGs’ experiences. This foundational analysis focuses on four recurrent and unifying themes that characterize IMGs’ practice environments and professional interactions: 1) IMGs experience both overt and subtle forms of workplace bias and discrimination; 2) IMGs recognize professional limitations as part of “the deal”; 3) IMGs describe challenges in the transition to the culture and practice of medicine in the US; 4) IMGs bring unique skills and advantages to the workplace. Future analyses will explore data related to supports for IMGs, and the individual and policy implications of IMGs’ contribution to the “brain drain” phenomenon.

IMGs Experience Both Overt and Subtle Forms of Workplace Bias and Discrimination

IMGs in our study reported instances of bias and discrimination, occurring at all levels of workplace interaction: with patients, with colleagues and with supervisors. For some, intimidation was a key element, as described an internist from sub-Saharan Africa:

The director of medicine was in morning report… he became a little bit overbearing and I think I made a comment to myself or something. ‘What was that?’ he said… ‘I'm going to ship you back to your country’…it kind of really got me angry. But that's the kind of atmosphere … they treat you like a beggar.

Other examples were less overt, originating from or conveyed by institutional leadership. This pediatrician from the Middle East recalled:

They would say, we are very happy to announce … this year residents were American graduates, not foreign … not the bad quality, the good quality… I think you shouldn’t say that … There are people in there who are not American grads, and they will feel bad when you say that.

Workplace bias and discrimination also occurred at a more systematic level. This pediatrician from sub-Saharan Africa described the clustering of IMGs in less-desirable specialties:

I think the interesting phenomenon … about immigrant doctors to the United States is that they always have filled the vacuum in those areas where nobody really wants to practice. I mean, I don’t sort of equate myself to a Mexican tomato picker, but [immigrant] physicians have filled those roles.

Finally, regardless of the length of time participants had practiced in the US, and despite the fact that all had completed residency training in the US, IMGs perceived that they were held to a different standard than USMGs. A family practitioner from Southeast Asia observed:

Even if you are accepted, you are not validated in a lot of systems… Though you have done your residency here, your training here …if you go into big hospitals, big organizations, you don’t see top level international medical people… You are being accepted by your patients… as a good doctor, but your work as a physician in a hospital setting … it is not validated by the higher authority… a medical director or somebody in that area ...

IMGs Recognize Professional Limitations as Part of “The Deal”

Participants cited limitations to professional opportunities as a result of being an IMG, including limitations in choice of geographic location, field of specialty or opportunities for advancement within their field. At the same time, IMGs acknowledged these professional limitations as a transactional cost of living and working as physicians in the US. This internist from Southeast Asia commented:

You kind of knew that getting in, look, it won’t be a completely open road … so I don’t think it bothered me personally and many of my colleagues when we were told you can’t apply for this residency or this fellowship or this job … it’s sort of part of the deal.

He went on to describe being passed over for promotions due to his IMG status:

All of the chosen ones, all the chief residents and people who were given … plumb things, were all U.S. graduates obviously. That was clearly there… maybe we were a little bit underclass but you know back then you are not a citizen … you are thankful for what is given to you and … you don’t complain.

An important aspect to “the deal” described by participants is that although IMGs reported numerous obstacles to professional advancement in the US, they also perceived that on balance, professional opportunities were greater in the US than in their home countries. This family practitioner from East Asia stated:

If I had stayed in [home country], there is no professorship for a female doctor ... The whole entire hospital, there were like two female professors and everybody else was male. It was a very male dominant society… I felt like I had a better chance pursuing that academic career in America.

IMGs Describe Challenges in the Transition to the Culture and Practice of Medicine in The US

Participants reflected on the experience of transitioning to the US and the particular challenges of this period. A family practitioner from the Middle East recalled learning about normative work-related procedures, such as interviewing for residency:

The Americans, they grow up in the system… They know what to say and when to say it and how to say it… Where I grew up there is no such thing as interview … it took me years just to learn how to sit and interview, how to walk in the room for an interview… all these things, they really matter here … every move is important to them and they just analyze you before you even say a word.

Participants also reported difficulties learning about subtle aspects of language, such as use of colloquialisms, sarcasm and idioms. This internist from Latin America recalled:

People sometimes … can use a joke with you because you don’t know a phrase or you don’t know something very common for the culture that you are in ... I remember one time someone told me, ‘don’t pull my leg’, and I am like, ‘I am not touching your leg’... sometimes it actually makes me feel uncomfortable.

Participants perceived a loss of autonomy as physicians in the US, with its emphasis on shared decision making, in contrast to experiences in their home countries. This internist from Latin America shared:

The challenge is when you come and you already have your preformed way to treat and deal with patients and you have to start from scratch and then readjust again to a new way to perceive patient autonomy and the ways that you have to deal with different situations. So … [in home country] sometimes we just tell them, this is how we are going to treat you. Period ... Once you have to switch to the model in America that you have to give them extra choices and more, sometimes it is challenging.

This loss of autonomy sometimes led to decreased confidence, as described by this pediatrician from Sub-Saharan Africa:

Traditionally in the state hospitals in [home country]… there was very little exposure to parents … of the babies … So there was very little discussion with families about illness. So basically you would treat the patient as you thought necessary. You didn’t have to explain anything. At a very junior level, you were allowed to do a lot more and have a lot more responsibility. So suddenly … every patient had a parent with them and … in a way it sort of made me feel less confident at times because I was trying to check if my skills were okay.

Finally, respondents were unaccustomed to the system of checks and balances in US healthcare and physicians’ sensitivity to potential litigation. This internist from Southeast Asia noted:

If somebody comes to see me, she has to register first… insurance… sign the papers. [Home country] is different … I’m coming from the hospital … and I see … an aunt and she’s sitting on the porch and she says … ‘Can you take my blood pressure?’... I’ll do that… I see another neighbor who is a … medical rep… I say ‘listen, what medicine you have for blood pressure?’ He gives some medicine. And I give it to the aunt… Here everything has to be official…I have to do this thing, that thing… something happens, they can blame me… it’s the law... they can sue me.

IMGs Bring Unique Skills and Advantages to the Workplace

IMGs viewed aspects of their prior training and clinical practice as professional assets, identifying skills and advantages gained through experience in another health care system and socio-cultural context. This pediatrician from the Middle East commented:

You have seen things that nobody else has seen … I used to see meningitis every day … because they don’t have vaccines in [home country]. So, I had this child with meningitis… And I called the infectious disease specialist ... She said, ‘this is my first case ever’ … you feel that you are giving them some experience. That’s an asset you have ... all of the foreign graduates carry with them some sort of a different type of approach to cases and they have a lot of clinical skills that is not available for a lot of medical students and medical doctors [here].

For some respondents, outsider status allowed them to better empathize with patients from ethnic/racial minority groups. This internist from Latin America said:

It is not that you are predisposed or you empathize more with people from your same background, but … sometimes you can help them better … you know how they think…what priorities they have… you can help them how to understand the system … especially minorities, when you can empathize sometimes how they struggle to get through the system …and how they are perceived. I don’t think you give them special treatment, but you try to find ways how to be effective.

DISCUSSION

We conducted an in-depth, systematic exploration of the professional experiences of non-US born IMGs physicians in primary care practice in the US. Participants reported nuanced, isolating and difficult interactions within workplace hierarchies, and both positive and negative relationships with patients and colleagues. They described “the deal” between IMGs and the US healthcare system, in which IMGs derive certain benefits from practicing medicine in the US, though their professional opportunities are constrained in multiple ways. Finally, they encountered procedural, cultural and systems-related obstacles during the period of transition and throughout their careers.

While participants reported difficulties with colloquialisms, accents and other subtleties of language in the transitional period, they did not specifically describe language barriers as a significant issue. This may be attributable to the requirement for IMGs to demonstrate English language competency, initially through written exams such as the TOEFL, and more recently through oral, interactive evaluations of language and communication such as the Clinical Skills Test. While such exams may initially result in increased expense and anxiety, they may also serve as practical preparation to function in the language of the US healthcare system.

Notably, our findings reveal a number of parallels between the experiences of IMGs and those of other minority groups working within the US healthcare system, including physicians from under-represented racial/ethnic minority groups,23–28 women physicians,28–30 and international graduates in other health professions such as nurses31–35 and nurses assistants.36 Overlapping domains of experience include social isolation,23,26,33,34 difficulties with professional advancement,24,27,33,35,37 and the challenges of navigating the workplace environment.23,25,31 Despite the parallels between IMGs and other groups of health care professionals, our findings remain distinct and novel because we characterized common experiences throughout the careers of a racially, ethnically and linguistically heterogeneous group of IMGs, while placing their experience in the context of the implicit and explicit tradeoffs they make.

Our findings suggest multiple opportunities to optimize the professional experiences of IMGs. These mechanisms fall broadly within the domains of education,38 acculturation strategies,39 and enhanced support, particularly during transitional periods.40 In addition, workplace and workforce policies may mitigate both subtle and explicit limitations to IMGs’ professional opportunities. Institutional review of policies to insure that the organizational climate does not perpetuate bias or discrimination is warranted. Efforts at cultural awareness in the workplace should include sensitivity to the issues of IMGs and the often subtle forms of discrimination they face. It is important to note that, in light of the parallels between the experiences of IMGs and the experiences of other health care professionals, efforts to optimize the workplace experiences of IMGs may also optimize the experiences of other groups of health care professionals, particularly traditionally marginalized populations.

The US is not alone in its reliance on IMGs. The United Kingdom (UK), Canada and Australia, among other developed nations, depend on IMGs for 20–30% of their physician workforce and experiences of IMGs have been documented in many of these nations,41–43 resulting in changes to discriminatory hiring practices, clarification of career advancement pathways and codification of mentoring relationships between junior and senior physicians.

There are a number of strengths to this study. The sampling frame was purposeful in order to achieve maximum variation in career experience. Our sample achieved diversity along several key dimensions including age, specialty, geographic regions of origin and years of clinical experience in the US. Despite this diversity, the common experience of being IMGs was reflected in the recurrent and unifying themes reported. We also utilized a number of recommended strategies to insure rigor: consistent use of an interview guide; audio-taping and independent transcription; standardized coding and analysis; use of researchers with diverse racial/ethnic and professional backgrounds; an audit trail to document analytic decisions; and participant confirmation in which participants reviewed a summary of the data and endorsed the content of the themes.16,17,22 Third, our high participation rate suggests that this is an issue IMGs are motivated to discuss in a research study, despite the potentially personal and sensitive nature of the topic.

Our findings should also be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, our study was designed to use qualitative methods to understand the complex experiences of IMGs through purposeful sampling to achieve wide variation. While our findings therefore cannot be generalized to all IMGs, we have generated hypotheses to be tested in future research using quantitative methods with large, representative samples. In addition, we focused on IMG physicians in outpatient primary care because of the concentration of IMGs in these fields, and the intimate nature of relationships between physician and patients in this setting. Experiences of IMG physicians in other specialties may warrant specific focus in future studies, particularly IMGs in surgical fields and sub-specialties with less intimate and longitudinal relationships with patients. Our study was geographically circumscribed to New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, largely metropolitan regions of the country. Other geographic regions, particularly rural areas, may represent a substantially different environment for IMGs.

Other future studies should examine areas of overlap between our findings and those of under-represented minority physicians and international graduates in other health professions. Interventions with such wide-reaching potential may require a more nuanced approach to examine their effects on different groups in the healthcare system. In addition, previous studies demonstrating that IMGs report lower career satisfaction than USMGs12–14 are concerning because dissatisfied physicians report greater intent to leave current practice;44 high physician job turnover disrupts patient care and is costly to physician practices;45 and physician career satisfaction correlates strongly with patient satisfaction.46 The reasons for these differential satisfaction rates can help focus future workforce and workplace policy changes. Finally, the contribution of IMGs to brain drain in their countries of origin and their personal conflict surrounding this is a vital aspect of the experience of IMGs and deserves further analysis and exploration.

CONCLUSION

IMGs represent a significant part of a heterogeneous primary care workforce delivering care to an increasingly diverse patient population. Yet, participants in our study perceived that their status as IMGs led to nuanced, isolating and difficult interactions within workplace hierarchies as well as both positive and negative patient interactions. Our findings suggest that the locus of action for optimizing the professional experiences of IMGs may include interventions aimed at IMGs themselves, as well as broad policy and practice changes in the systems and structures in which IMGs work. Finally, attempts to optimize the experiences of IMGs may also improve the experiences of other traditionally marginalized groups of health care professionals.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for funding and support; the American Medical Association IMG section for assistance in recruiting; the Educational Foundation for Foreign Medical Graduates for helpful comments; and all the international medical graduates whose participation made this study possible. MNS is supported in part by the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation and the Association of American Colleges Nickens Faculty Fellowship. Some of the information reported in this manuscript was presented at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars 2008 National Meeting (Washington DC, November 20, 2008); the American Association of Medical Colleges 2009 Workforce Conference (Washington DC, May 30, 2009); and the Academy Health 2009 Annual Research Meeting (Chicago IL, June 28, 2009).

Conflict of Interest MNS has received honoraria from Pfizer and Astro-Zeneca in conjunction with speaking at the American Osteopathic Association October, 2009 national meeting. PGC, LAC, DB, SMB and AG have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.AMA. IMGs in the United States. In: American Medical Association; 2007.

- 2.Smart D. Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US-2006. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.NRMP. Advanced Data Tables for 2007 Main Residency Match. In: National Residency Match Program; 2007. p. Table 5.

- 4.Polsky D, Kletke PR, Wozniak GD, Escarce JJ. Initial practice locations of international medical graduates. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(4):907–28. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.58.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao V, Cabbabe E, Adams K, et al. International medical graduates in the U.S. Workforce. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2007.

- 6.Hing E, Lin S. Role of international medical graduates providing office-based medical care: United States, 2005–2006. NCHS Data Brief. 2009(13):1–8. [PubMed]

- 7.Cohen JJ. The role and contributions of IMGs: a U.S. perspective. Acad Med. 2006;81(12 Suppl):S17–21. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000243339.63320.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hart LG, Skillman SM, Fordyce M, Thompson M, Hagopian A, Konrad TR. International medical graduate physicians in the United States: changes since 1981. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(4):1159–69. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulet JR, Norcini JJ, Whelan GP, Hallock JA, Seeling SS. The international medical graduate pipeline: recent trends in certification and residency training. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(2):469–77. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akl EA, Mustafa R, Bdair F, Schunemann HJ. The United States physician workforce and international medical graduates: trends and characteristics. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):264–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0022-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gozu A, Kern DE, Wright SM. Similarities and differences between international medical graduates and U.S. medical graduates at six Maryland community-based internal medicine residency training programs. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):385–90. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318197321b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris AL, Phillips RL, Fryer GE, Jr, Green LA, Mullan F. International medical graduates in family medicine in the United States of America: an exploration of professional characteristics and attitudes. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4:17. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoddard JJ, Hargraves JL, Reed M, Vratil A. Managed care, professional autonomy, and income: effects on physician career satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(10):675–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leigh JP, Kravitz RL, Schembri M, Samuels SJ, Mobley S. Physician career satisfaction across specialties. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(14):1577–84. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.14.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiscella K, Roman-Diaz M, Lue BH, Botelho R, Frankel R. 'Being a foreigner, I may be punished if I make a small mistake': assessing transcultural experiences in caring for patients. Fam Pract. 1997;14(2):112–6. doi: 10.1093/fampra/14.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malterud K. The art and science of clinical knowledge: evidence beyond measures and numbers. Lancet. 2001;358(9279):397–400. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05548-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Britten N. Qualitative interviews in medical research. BMJ. 1995;311(6999):251–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO. Physician density per 1,000 population. In: World Health Organization; 2007.

- 20.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis : an expanded sourcebook. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation. 2009;119(10):1442–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.742775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liebschutz JM, Darko GO, Finley EP, Cawse JM, Bharel M, Orlander JD. In the minority: black physicians in residency and their experiences. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(9):1441–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nunez-Smith M, Curry LA, Bigby J, Berg D, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH. Impact of race on the professional lives of physicians of African descent. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(1):45–51. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-1-200701020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gartland JJ, Hojat M, Christian EB, Callahan CA, Nasca TJ. African American and white physicians: a comparison of satisfaction with medical education, professional careers, and research activities. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15(2):106–12. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1502_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Post DM, Weddington WH. Stress and coping of the African-American physician. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92(2):70–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang D, Moy E, Colburn L, Hurley J. Racial and ethnic disparities in faculty promotion in academic medicine. JAMA. 2000;284(9):1085–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.9.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corbie-Smith G, Frank E, Nickens HW, Elon L. Prevalences and correlates of ethnic harassment in the U.S. Women Physicians' Health Study. Acad Med. 1999;74(6):695–701. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199906000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bickel J. Gender stereotypes and misconceptions: unresolved issues in physicians' professional development. JAMA. 1997;277(17):1405–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.17.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carr PL, Ash AS, Friedman RH, Szalacha L, Barnett RC, Palepu A, et al. Faculty perceptions of gender discrimination and sexual harassment in academic medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(11):889–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-11-200006060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yi M, Jezewski MA. Korean nurses' adjustment to hospitals in the United States of America. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(3):721–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magnusdottir H. Overcoming strangeness and communication barriers: a phenomenological study of becoming a foreign nurse. Int Nurs Rev. 2005;52(4):263–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2005.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dicicco-Bloom B. The racial and gendered experiences of immigrant nurses from Kerala, India. J Transcult Nurs. 2004;15(1):26–33. doi: 10.1177/1043659603260029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hagey R, Choudhry U, Guruge S, Turrittin J, Collins E, Lee R. Immigrant nurses' experience of racism. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33(4):389–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torres S, Castillo H. Bridging cultures: Hispanics/Latinos and nursing. In: McCloskey J, Grace H, editors. Current issues in nursing. 5. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997. pp. 574–579. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allensworth-Davies D, Leigh J, Pukstas K, Geron SM, Hardt E, Brandeis G, et al. Country of origin and racio-ethnicity: are there differences in perceived organizational cultural competency and job satisfaction among nursing assistants in long-term care? Health Care Manage Rev. 2007;32(4):321–9. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000296788.31504.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coombs AA, King RK. Workplace discrimination: experiences of practicing physicians. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(4):467–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cole-Kelly K. Cultures engaging cultures: international medical graduates training in the United States. Fam Med. 1994;26(10):618–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porter JL, Townley T, Huggett K, Warrier R. An acculturization curriculum: orienting international medical graduates to an internal medicine residency program. Teach Learn Med. 2008;20(1):37–43. doi: 10.1080/10401330701542644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bates J, Andrew R. Untangling the roots of some IMG's poor academic performance. Acad Med. 2001;76(1):43–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200101000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant J, Jones H, Kilminster S, Macdonald M, Maxted M, Nathanson B, et al. Overseas Doctors' Expectations and Experiences of Training and Practice in the UK. Milton Keynes: Open University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han GS, Humphreys JS. Overseas-trained doctors in Australia: community integration and their intention to stay in a rural community. Aust J Rural Health. 2005;13(4):236–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2005.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klein D, Hofmeister M, Lockyear J, Crutcher R, Fidler H. Push, pull, and plant: the personal side of physician immigration to alberta, Canada. Fam Med. 2009;41(3):197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Landon BE, Reschovsky JD, Pham HH, Blumenthal D. Leaving medicine: the consequences of physician dissatisfaction. Med Care. 2006;44(3):234–42. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000199848.17133.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buchbinder SB, Wilson M, Melick CF, Powe NR. Estimates of costs of primary care physician turnover. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5(11):1431–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Cleary PD, Brennan TA. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(2):122–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]