ABSTRACT

Background

Unfavorable results of major studies have led to a large shrinkage of the market for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in the last 6 years. Some scientists continue to strongly support the use of HRT.

Objectives

We analyzed a sample of partisan editorializing articles on HRT to examine their arguments, the reporting of competing interests, the journal venues and their sponsoring societies.

Data Sources

Through Thomson ISI database, we selected articles without primary data written by the five most prolific editorialists that addressed clinical topics pertaining to HRT and that were published in regular journal issues in 2002–2008.

Main Measures

We recorded the number of articles with a partisan stance and their arguments, the number of partisan articles that reported conflicting interests, and the journal venues and their sponsoring societies publishing the partisan editorials.

Key Results

We analyzed 114 eligible articles (58 editorials, 16 guidelines, 37 reviews, 3 letters), of which 110 (96%) had a partisan stance favoring HRT. Typical arguments were benefits for menopausal and related symptoms (64.9%), criticism of unfavorable studies (78.9%), preclinical data that showed favorable effects of HRT (50%), and benefits for major outcomes such as osteoporosis and fractures (49.1%), cardiovascular disease (31.6%), dementia (24.6%) or colorectal cancer (20.2%), but also even breast cancer (4.4%). All 5 prolific editorialists had financial relationships with hormone manufacturers, but these were reported in only 6 of the 110 partisan articles. Four journals published 15–37 partisan articles each. The medical societies of these journals reported on their websites that several pharmaceutical companies sponsored them or their conferences.

Conclusions

There is a considerable body of editorializing articles favoring HRT use and very few of these articles report conflicts of interest. Full disclosure of conflicts of interest is needed, especially for articles without primary data.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1360-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: hormone replacement therapy, menopause, postmenopausal women

INTRODUCTION

When evidence suggests that the large proportion of a blockbuster market and of the activities of a medical specialty are unjustified, both the industry and medical specialists may try to challenge this evidence to maintain the status quo. Some debate is entirely healthy and may include the conduct of more studies or scrutiny of existing studies. However, other efforts may be spurious, such as industry-sponsored ghostwriting of favorable articles with academic authors to advance sales of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) use in menopausal women.1

HRT has attracted wide attention in the scientific literature and the media. Until 2002, the HRT market had annual sales of many billions of dollars.1 Handling menopause symptoms nurtured the specialty of menopause medicine and gynecological endocrinology. After 2002, however, the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI)2 and the Million Women Study (MWS)3 demonstrated considerable harms and more modest benefits from HRT. Currently, perceived harms include increased risks of breast cancer, heart disease, strokes and possibly dementia, and perceived benefits include decreased risks for colorectal cancer, and fractures–besides control of menopausal symptoms. There is still debate on whether specific subgroups/settings exist in which there are more favorable risk-benefit ratios. However, the results of the WHI and MWS studies markedly decreased the use of HRT in the community.4,5 Most scientific and public health organizations currently advocate that HRT should have limited, circumscribed, short-term focused applications, not wide use.6–9 It is not surprising that this change in clinical practice recommendations would encounter opposition.

Between healthy debate on one hand and drug industry-driven articles on the other, one may identify investigators who genuinely believe in HRT and ardently write supportive editorials, reviews, or other pieces without primary data. The aim of our study was to evaluate how partisan supporters of an intervention continue to defend its wider use despite unfavorable evidence. We identified authors who have published a large number of HRT-favoring editorials and related articles without primary data. We scrutinized their typical arguments and disclosure of potential conflicts of interest, and examined whether these articles originate from specific journals and medical societies.

METHODS

Literature Search

We aimed to identify articles without primary data that discussed clinical issues of menopausal hormone therapy and that had been written by authors who had published far more editorializing articles on this subject than other scientists. We first performed a literature search in Thomson ISI with the search strategy estrogen OR hormone replacement OR progestin OR menopause OR postmenopausal OR WHI OR “Women’s Health Initiative” limited to the period 2002–2008 (last search performed on January 4, 2009). In this reference corpus, we identified items that are characterized as “Editorial material” by Thomson ISI. We then selected the five authors who had published the largest number of such “Editorial material” items pertaining to HRT in this period.

Many other articles that have no primary data and contain considerable editorializing (e.g., guidelines and reviews) are not included under the “Editorial material” Thomson ISI tag. Therefore, at a second stage, we retrieved all the publications of these selected authors in the reference corpus and evaluated in-depth all their publications that did not report primary data. We then excluded the items that appeared in supplements or proceedings, since they are difficult to locate and usually have less impact in the literature. If anything, this exclusion makes our analysis more conservative, since supplements and proceedings can more easily harbor industry-sponsored articles and hyper-partisan conclusions. For publications in regular journal issues, we retrieved the full text and examined whether there was any discussion of clinical issues on hormones. If so, the article was considered eligible for analysis.

Evaluation of Eligible Articles

For each eligible article, we extracted the following information: title; type of article (editorial; guideline, consensus, or position statement; non-systematic review; systematic review; or letter-to-the-editor); whether clinical issues were the primary focus of the article or not; whether the article had a partisan stance; and, if so, what types of arguments were raised.

The stance of an article was deemed as partisan if there were overall statements in favor of HRT highlighting only benefits or highlighting benefits more than harms, statements making pleas for increased use, or statements criticizing decreased use or criticizing restrictive guidelines. For partisan articles, we noted whether each of the following types of arguments were raised: statements that HRT is effective for menopausal and related symptoms; discussion of preclinical data that showed favorable effects for hormones under at least some circumstances; statements challenging or criticizing studies with unfavorable results for HRT (and if so, whether WHI or MWS were criticized); and statements that HRT may decrease the risk of life-threatening or other serious outcomes (and if so, which). Finally, we recorded whether the article focused on claiming that some form or setting of hormonal therapy could be particularly beneficial (more effective and/or less harmful) and if so what form or setting was described.

Funding and Conflicts of Interest

In each article of the five most prolific authors, we recorded any disclosed funding source or conflicts of interest. We also examined whether any conflicts of interest were disclosed in any of the analyzed articles. If no conflict was disclosed, we further checked whether they may have co-authored any guidelines, consensus and position statements in their career in any topic where they may have provided such information.

Evaluation of Journals and Societies

For journals that had published over ten eligible articles with a partisan stance, we identified through the web their affiliated scientific society, editorial boards, Thomson Journal Citation Reports 2007 impact factor and proportion of same-journal citations (citations made from other articles published in the same journal). We also examined whether the societies had any corporate sponsors either for their activities overall or for their main scientific meetings, as per their web sites.

Data extraction on all articles including the decision on whether they stated a “partisan” stance for HRT was performed independently by two investigators, and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

RESULTS

Analyzed Articles

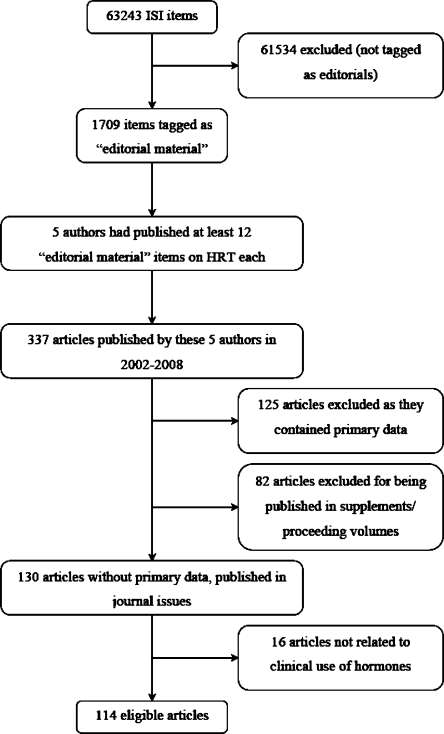

The ISI search yielded 63,243 items in the reference corpus; 1,709 were classified as “Editorial material” (Fig. 1), and 2,935 different author names were involved in them. The 1,709 items were published in 426 different journals. The vast majority of authors (2,897/2,935, 98.7%) had authored 1–4 such articles each, and 1.1% (32/2,935) had authored 5–12 such articles each, while 6 authors had published more than 12 “Editorial material” items. Five of these six authors editorialized primarily about clinical issues on HRT, and they stood clearly apart in the number of HRT-related editorials compared with all other authors. These five scientists were all active in the field of gynecological endocrinology and had published 337 articles included in the reference corpus during 2002–2008. After excluding articles with primary data, items published in meeting supplements or proceedings, and articles without discussion of hormone-related clinical issues, 114 articles were evaluated in-depth (Fig. 1; included articles are listed in online Appendix 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart.

Partisan Stance

Several titles were already clearly suggestive of a partisan, if not polemical, stance, for example, “WHI, WHI, WHI?” (S65), “Risks for healthy women in the WHI greatly overestimated according to new publications” (S73), “Should epidemiology, the media and quangos determine clinical practice?” (S77), “The sound of an International anti-HRT herald!” (S85), “The study with a million women (and hopefully fewer mistakes)” (S86), “A personal initiative for women's health: to challenge the Women’s Health Initiative (S107)” (full list appears in online Appendix 2).

Of the 114 articles, 58 were editorials, 16 were guidelines, consensus or position statements, 35 were non-systematic reviews, two were systematic reviews, and three were letters-to-the-editor. Of the 58 editorials, only 7 were written to comment on a specific article with primary data that was published in the same issue of the journal. All the others were impromptu statements favoring HRT or arguments against WHI. For 95 articles, the clinical issues were the primary focus of the article. One hundred ten articles (96%) were deemed to have a partisan stance (98% agreement between data extractors). Of the non-partisan articles, one was a systematic review, and three were non-systematic reviews.

Table 1 shows the various types of partisan arguments, and verbatim examples appear in online Appendix 3. Two-thirds of the articles highlighted the effectiveness of HRT for menopausal and related symptoms, half discussed pre-clinical data showing favorable effects, most articles had statements criticizing WHI and one out of five challenged MWS. Furthermore, several articles included statements that HRT may decrease life-threatening or other serious outcomes. Osteoporosis/fractures were mentioned by about half the articles, a third discussed benefits for cardiovascular disease, and a quarter discussed benefits for dementia. Numerous other benefits were discussed (Table 1), including even claims for reduction of breast cancer risk.

Table 1.

Types of Partisan Arguments in 114 Analyzed Editorializing Articles Published Between 2002 and 2008

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| HRTa is effective for menopausal and related symptoms | 74 (64.9) |

| Discussion of preclinical data that showed favorable effects for HRT | 57 (50.0) |

| Statements challenging/criticizing unfavorable studies | |

| Against WHIb | 89 (78.1) |

| Against MWSc | 29 (25.4) |

| Statements that HRTa may decrease life-threatening and other serious outcomes | |

| Breast cancer | 5 (4.4) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 36 (31.6) |

| Stroke | 2 (1.8) |

| Dementia | 28 (24.6) |

| Ovarian cancer | 0 |

| Endometrial cancer | 2 (1.8) |

| Colorectal cancer | 23 (20.2) |

| Osteoporosis/fractures | 56 (49.1) |

| Other | |

| Hypertension | 3 (2.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (2.6) |

| Depression | 10 (8.8) |

| Metabolic syndrome | 2 (1.8) |

| Osteoarthritis | 3 (2.6) |

aHRT: hormone replacement therapy; bWHI: Women’s Health Initiative; cMWS: Millon Women Study

Some arguments were phrased in a repetitive fashion across different articles, even to the point of having, in some cases, whole sentences or paragraphs repeated almost verbatim. Moreover, sometimes the same article was apparently published by the same or overlapping authors two or three times in the same or in different journals—in English, or in English and in German—during the same period of time without referencing each other (examples in online Appendix 4).

Twenty-two articles made suggestions or clearly stated that some form or setting of hormonal therapy could be particularly beneficial. Specifically, eight articles focused on a specific type of hormone, seven on time of therapy initiation and one on patient age, six on route of administration, two on dose, two on use in non-smokers, one on hypertensive patients, and one on co-administration with another drug.

Funding and Conflicts of Interest

Four articles clearly stated there was no funding, and eight reported funding sources (five reported support from a pharmaceutical company and three from a private foundation for art and culture). Five articles clearly stated there were no conflicts of interest and five reported potential conflicts (four of which consisted of relationships with pharmaceutical companies involving consultative agreements, honoraria for lecturing at scientific meetings or research support). Six of the eight articles that reported funding sources and all five articles stating potential conflicts had a partisan stance. Of the 16 guidelines, consensus and position statements, only 2 reported on funding sources, and only 1 reported conflicts of interest.

All five prolific authors disclosed in at least one of their articles that they had been funded by industry or that they had been related to some potential conflict of interest. However, these relationships with hormone manufacturers were revealed in only 6 of their 110 partisan articles; in the other 104 articles, no such disclosure was stated.

Journals and Societies

The 110 articles with a partisan stance were published in 19 different journals, but most (91/110) appeared in just 4 journals that published 15 to 37 articles each (Table 2). These journals are the official scientific journals of societies related to menopause and gynecological endocrinology. Their impact factor varies from 0.502 to 2.275. The journal with the lowest impact factor has an extremely high same-journal citation rate (88%, 95% CI 82%–94%). The other three have same-journal citation rates of 13–19%. These three journals also had relationships with the five authors we evaluated: one to three of these five authors sit on the editorial boards of each of these three journals. Evaluation of websites of the societies that publish these journals showed that almost all of these societies have disclosed some relationships with manufacturers of HRT medications. The International Menopause Society organizes workshops sponsored by several pharmaceutical companies. The European Menopause and Andropause Society is sponsored by Wyeth, which is mentioned as a corporate member at the society’s website. The International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology organizes the World Congress of Gynecologic Endocrinology, which is supported by several companies. Finally, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe has pharmaceutical company prizes awarded at its congresses.

Table 2.

Journals Publishing the Largest Number of Partisan Editorials and Related Articles Without Primary Data Between 2002 and 2008

| Journala | Articles | Scientific society | Impact factor | Self-cites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climacteric | 37 | IMSb | 2.275 | 39/207 |

| Maturitas | 20 | EMASc | 2.023 | 100/615 |

| Gynecological endocrinology | 19 | ISGEd | 1.169 | 34/277 |

| Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde | 15 | DGGGe /OEGGGf | 0.502 | 103/117 |

aNineteen journals published the 110 partisan articles that we analyzed, but the 15 journals not shown here had each published only 1–3 such articles

bIMS: International Menopause Society

cEMAS: European Menopause and Andropause Society

dISGE: International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology

eDGGG: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics)

fOEGGG: Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (Austrian Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics)—no web site was identified for OEGGG

INTERPRETATION

We have identified a substantial body of editorializing literature that has a partisan stance in favor of HRT. These articles include mostly editorials, non-systematic reviews, guidelines and consensus statements. They use a standard armamentarium of arguments to support HRT and to criticize the large studies that demonstrated problems with HRT. Similar arguments are repeated across different articles. Four journals have contributed most of the editorializing literature that we analyzed. Both the prolific editorializing authors and the professional societies publishing these journals had relationships to the pharmaceutical industry. However, only 6 of the 110 partisan articles specifically mentioned any such funding or conflicts of interest.

Experience from other fields suggests that even when large trials contradict previous beliefs about the benefits of various interventions, a section of the medical literature continues to support previous practices and raises counterarguments as to why the large studies were wrong. This “die hard” pattern has been demonstrated in vitamin E for cardiovascular prevention, beta-carotene for cancer prevention, estrogen for dementia prevention10 and percutaneous coronary intervention for stable chronic coronary artery disease11 (in the latter case, the source of resistance came primarily from interventional cardiologists).12 Moreover, the key vehicle of expressing doubts about large trials has been through editorials and expert statements. Similarly, our study documents a large literature of editorializing articles that emanate from authors and societies involved in the promotion of HRT.

Defending one’s practices is not unethical, and many of the arguments raised have some validity or may even be correct. The authors of these articles may be excellent scientists. However, it is concerning that almost none of these partisan articles reported the conflicts of interest of their authors. Obviously, the average reader would not have time to investigate the whole publication corpus of an author to determine whether he or she ever reported any conflicts of interest. Omission of conflicts of interest was prominent not only for short editorials, but also for guideline and consensus articles that were typically sponsored by these professional societies. As of January 2010, three of the four journals that hosted most of the editorializing articles clearly reported (in their instructions to authors) that authors should disclose any conflicts of interest in their manuscripts, and the fourth journal (Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde) mentioned that authors should provide notes for financial or other support in a footnote at the end of the text. Given that these instructions to the authors are online, it is unclear when these policies where implemented. Reporting of conflicts is a responsibility both of the editorialists and of the journals that should ensure that transparent reporting of conflicts is actually enforced.

Most professional societies have industry ties: industry sponsors their meetings, provides awards/grants, and maintains a team of speakers from society members. Societies sponsor and publish scientific journals, and propagate practice guidelines that influence their members. This creates intricate relationships with industry,12–21 especially for societies whose core practice is related to specific products, as is the case for menopause specialists and HRT.

Pharmaceutical involvement in research may affect study design, focus and results,22–25 and authors’ published positions correlate with financial relationships with manufacturers in review articles and letters to the editor.26 There are also strong interactions between industry and authors of practice guidelines.27 Otherwise excellent scientists may be tempted to produce editorials with non-evidence-based claims. Almost all major field experts have potential financial conflicts; while it is hard to find experts without any conflicts,28 disclosure is essential.29

We built our search for eligible articles around the most prolific partisan editorialists, and this is just a selected fraction of all the editorials written on HRT. However, these authors clearly stood apart in the volume of their editorializing articles when compared with the other 3,000 authors who have written mostly sporadic editorials. Similarly, four specialty journals clearly stood apart in the volume of partisan editorializing items compared with all other journals that may have some interest in the field. The cumulative impact on clinical practice is shaped by diverse opinion leaders, both those who write numerous partisan articles and those who may write a few non-partisan ones. For HRT, most high-impact authorities have made conservative statements about its use. This includes the American Heart Association7, the North American Menopause Society8, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care9 and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists6 (the first three of these also report conflicts of interest in their publications). The cumulative influence of these major authorities is apparently higher than that of concentrated partisan publications in journals with modest impact. Moreover, hundreds of journals published editorials on HRT, and most of them published only a few such items. Even single editorials may have a considerable impact, especially if published in high-impact journals. However, most high-impact general medical journals have very strict policies for conflicts of interest and stringent review filters. Extremely partisan positions may be more difficult to publish in editorials in such journals. Specialty journals sponsored by professional societies may thus be a more convenient publication venue for partisan editorialists.

Finally, we do not wish to make claims about the underlying motives for each article in the partisan literature. Previous studies30–33 have pointed even to guest authorship and ghostwriting practices in developing a pro-industry literature. For HRT in particular, several months ago an investigation was announced by Senator Grassley1 claiming that Wyeth and leading HRT experts were involved in ghost- and guest-authorship favoring Prempro (a combination of estrogen and progestin). Recently, the Institute of Medicine suggested that medical schools should abandon long-accepted relationships with the industry and practices that create conflicts of interest, threaten the integrity of their missions and their reputations, and jeopardize public trust.34 Nonetheless, we do not intend to blame the authors of the specific articles we examined. The mere wish to defend one’s practice, procedures and scientific beliefs may be sufficient explanation, and all the authors involved in these articles may have been fully responsible for and sincere in their writings. However, this complex background where large drug markets are at stake further highlights the need for full disclosure of conflicts of interest to promote discernment among readers and prevent mistrust.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 51 kb)

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions Dr. Ioannidis had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding/Support None

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilson D. Wyeth’s Use of Medical Ghostwriters Questioned. New York Times. December 13, 2008:B1 (Accessed on March 2010 at http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/13/business/13wyeth.html?_r=1&ref=business)

- 2.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Million Women Study Collaborators Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet. 2003;362:419–427. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hersh AL, Stefanick ML, Stafford RS. National use of postmenopausal hormone therapy: annual trends and response to recent evidence. JAMA. 2004;291:47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson J, Wise L, Green J. Prescribing of hormone therapy for menopause, tibolone, and bisphosphonates in women in the UK between 1991 and 2005. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:843–849. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ACOG Task Force for Hormone Therapy American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Women’s Health Care Physicians Summary of balancing risks and benefits. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:128S–129S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000138791.21105.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosca L, Appel LJ, Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2004;109:672–693. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114834.85476.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Recommendations for estrogen and progestogen use in peri-and postmenopausal women: October 2004 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2004;11:589–600. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Wathen CN, Feig DS, Feightner JW, Abramson BL, Cheung AM. Hormone replacement therapy for the primary prevention of chronic diseases: recommendation statement from the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. CMAJ. 2004;170:1535–1537. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1030756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tatsioni A, Bonitsis NG, Ioannidis JP. Persistence of contradicted claims in the literature. JAMA. 2007;298:2517–2526. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.21.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siontis GC, Tatsioni A, Katritsis DG, Ioannidis JP. Persistent reservations against contradicted percutaneous coronary intervention indications: citation content analysis. Am Heart J. 2009;157:695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angell M. Drug companies. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. p. 251. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothman DJ, McDonald WJ, Berkowitz CD, et al. Professional medical associations and their relationships with industry: a proposal for controlling conflict of interest. JAMA. 2009;301:1367–1372. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sniderman AD, Furberg CD. Why guidelinemaking requires reform. JAMA. 2009;301:429–431. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinbrook R. Financial support of continuing medical education. JAMA. 2008;299:1060–1062. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.9.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothman DJ. Academic medical centers and financial conflicts of interest. JAMA. 2008;299:695–697. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.6.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehringhaus SH, Weissman JS, Sears JL, Goold SD, Feibelmann S, Campbell EG. Responses of medical schools to institutional conflicts of interest. JAMA. 2008;299:665–671. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Podolsky SH, Greene JA. A historical perspective of pharmaceutical promotion and physician education. JAMA. 2008;300:831–833. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.7.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell EG, Gruen RL, Mountford J, Miller LG, Cleary PD, Blumenthal D. A national survey of physician-industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1742–1750. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Relman AS. Medical professionalism in a commercialized health care market. JAMA. 2007;298:2668–2670. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brennan TA, Rothman DJ, Blank L, et al. Health industry practices that create conflicts of interest: a policy proposal for academic medical centers. JAMA. 2006;295:429–433. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.4.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peppercorn J, Blood E, Winer E, Partridge A. Association between pharmaceutical involvement and outcomes in breast cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2007;109:1239–1246. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vlad SC, LaValley MP, McAlindon TE, Felson DT. Glucosamine for pain in osteoarthritis: why do trial results differ? Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2267–2277. doi: 10.1002/art.22728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ioannidis JP. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ioannidis JP. Effectiveness of antidepressants: an evidence myth constructed from a thousand randomized trials? Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2008;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1747-5341-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stelfox HT, Chua G, O’Rourke K, Detsky AS. Conflict of interest in the debate over calcium-channel antagonists. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:101–106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801083380206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choudhry NK, Stelfox HT, Detsky AS. Relationships between authors of clinical practice guidelines and the pharmaceutical industry. JAMA. 2002;287:612–617. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angell M, Kassirer JP. Editorials and conflicts of interest. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1055–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kassirer JP, Angell M. Financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:570–571. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308193290810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinman MA, Bero LA, Chren MM, Landefeld CS. Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:284–293. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Healy D, Cattell D. Interface between authorship, industry and science in the domain of therapeutics. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:22–27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross JS, Hill KP, Egilman DS, Krumholz HM. Guest authorship and ghostwriting in publications related to rofecoxib: a case study of industry documents from rofecoxib litigation. JAMA. 2008;299:1800–1812. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.15.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Johansen HK, Haahr MT, Altman DG, Chan AW. Ghost authorship in industry-initiated randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education and Practice. Bernard Lo and Marilyn J. Eds. Report prepared by the Committee on Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine. National Academy Press; April 28, 2009. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 51 kb)