Abstract

Although it is a commonly used analgesic, acetaminophen can be highly hepatotoxic. This study seeks to further investigate the mechanisms involved in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity, as well as the role of CXCR2 receptor/ligand interactions in the liver’s response to and recovery from acetaminophen toxicity. The CXC chemokines and their receptor, CXCR2, are important inflammatory mediators, as well as being involved in the control of some types of cellular proliferation. CXCR2 knock out mice exposed to an LD50 dose of acetaminophen have a significantly lower mortality rate as compared to wild type mice. This difference is at least partially attributable to a significantly decreased rate of apoptosis in the CXCR2 knock out mice versus wild type; there were no differences seen in hepatocyte proliferation in wild types versus knock outs after this injury. The decreased rate of apoptosis in the knock out mice correlated with an almost undetectable and significantly decreased level of activated caspace-3, and significantly increased levels of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), which also correlated with increased levels of NF-KB p52 and decreased levels of JNK, providing a possible mechanism for the decrease in apoptosis seen in the CXCR2 knock out mice.

Introduction

Acute liver failure is common in patients admitted to the intensive care unit; in approximately 20% of cases of acute hepatic failure, the liver injury is related to acetaminophen (APAP) toxicity (1). The mechanism of APAP-induced liver injury involves the cytochrome P-450-generated metabolite, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine, which causes glutathione depletion, impairs mitochondrial respiration, and interferes with calcium homeostasis, although the actual events resulting in cell death are not well understood (2).

Apoptosis occurs in all cells and is regulated by cellular death and cellular survival signals. Imbalances in these signals can be lethal and likely play a role in many pathophysiologic processes. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), which is one of the inhibitor of apoptosis proteins family (IAPs), binds to and inhibits caspace-3 and caspace-9 and protects endothelial cells against tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated apoptosis (3). XIAP also inhibits apoptosis by another mechanism: a positive feedback loop which furthers NF-KB activation (3,4).

This paper investigates CXCR2 signaling in the apoptotic response to hepatic acetaminophen toxicity in the mouse. The CXC chemokines play a role in many inflammatory and regenerative processes and are the major ligands for the CXCR2 receptor. Studies demonstrate that CXC chemokines, including interleukin-8, macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP2), and KC, among others, have direct effects on hepatocytes. The CXCR2 receptor is expressed on hepatocytes (5), and that finding is confirmed in this study. In models of both partial hepatectomy and acetaminophen toxicity, CXCR2/ligand interactions promote hepatocyte proliferation and liver regeneration (4,6,7). In contrast, other investigators have found that CXCR2 ligands can be hepatotoxic (8).

Materials and Methods

Animal model

CXCR2 targeted mutant mice were generated by mating heterozygote C.129S2(B6)-Il8rbtm1Mwm/J mice (Il8rbtm1Mwm/Il8rb+) (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) in the University of Michigan animal facility. CXCR2 mutant (Il8rbtm1Mwm/Il8rbtm1Mwm) mice and CXCR2 wild type (Il8rb+/Il8rb+) mice were used in all experiments; wild type and mutant mice are based on the mouse 129 strain. All experiments were performed in compliance with the standards for animal use and care set by the University of Michigan’s Committee on the Use and Care of Animals.

Animals were fasted overnight and APAP or an equal volume of PBS was administered intraperitoneally (9). For mortality experiments, animals received 750 mg/kg or 1000 mg/kg APAP; for all other experiments, 375 mg/kg was utilized. Based on previous experiments in this strain of mouse, 750 mg/kg APAP is the approximate LD50 dose and 375 mg/kg is the approximate LD25 dose.

To confirm that apoptosis is important in the acetaminophen-induced liver injury in this model, additional experiments were performed using the pan-caspace inhibitor Q-VD-OPh. Q-VD-OPh is more effective at preventing apoptosis than other inhibitors, such as ZVAD-fmk and Boc-D-fmk and is non-toxic to cells, even at high doses (10). This compound prevents apoptosis mediated by the three major apoptotic pathways, caspace 9/3, caspace 8/10, and caspace 12 (10). Fifty mg/kg Q-VD-OPh (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) was administered 1 hour before APAP injection; control animals received an equivalent dose of vehicle. Animals were then sacrificed as per protocol and apoptosis measured by TUNEL staining and DNA fragmentation assay.

AST and ALT Assay

Serum AST and ALT were measured in CXCR2 knock out and wild type mice at 24, 48, and 72 hours after APAP or PBS. Animals were sacrificed, blood collected, and serum was separated from the clotted blood by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. ALT and AST were measured using Diagnostics ALT and AST test kit from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO).

Glutathione Assay

Mouse livers were perfused with perfusion medium (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) to remove intravascular blood. Ten milligrams of liver tissue was homogenized in 1 ml of PBS containing 2 mM EDTA. Fifty microliters of tissue extract was used for glutathione measurement. Glutathione was measure per the manufacture’s instructions using the Glutathione Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Luminescence was detected using a Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader with Gen5 Data Analysis software (BioTek, Winooski, VT).

DNA Fragmentation Assay

DNA was extracted from 25 mg of mouse liver. Total DNA purification was performed with DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MA) based on manufacture’s instructions. RNA was eliminated by incubation in 5 μg/ml RNase (Roche,Indianapolis, IN). A 1.5 μg DNA aliquot was loaded on 1.5% agarose gel for separation to assess for DNA fragmentation.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining

TUNEL staining was conducted using In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Six to seven animals were utilized per time point per treatment group. A minimum of 1000 cells (TUNEL positive cells and negative cells) were counted in each of eight separate low power fields for each animal and the percentage of TUNEL positive cells was calculated.

In vivo measurement of hepatocyte proliferation by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation

Two hours prior to sacrifice, animals received 30 μg BrdU/gram of body weight intraperitoneally. Liver specimens were obtained, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, processed for histologic analysis, and stained using the Amersham cell proliferation kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Limited, United Kingdom). BrdU incorporation was measured at 24, 36, 48, and 72 hours. There were 4-7 mice per treatment group per time point. A minimum of 1000 cells (BrdU positive cells and negative cells) were counted in each of eight separate low power fields for each animal and the percentage of BrdU positive cells was calculated.

Cytoplasmic and nuclear protein extraction

Hepatic cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were extracted using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) based on the manufacturer’s instruction.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

Liver samples were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS, 0.25% Na deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors). Four hundred micrograms of protein were used for immunoprecipitation. Lysate was precleared with 1 μg isotype IgG and 50 μl protein A/G agarose at 4°C for 1 hour. Five micrograms of immunoprecipitating antibody or isotype IgG was added to the supernatant and rocked overnight at 4°C. Next, 50 μl protein argarose was added and the mixture was rocked for 2 hours at 4°C. The protein bound to the agarose conjugate was centrifuged and the pellet was washed three times with RIPA buffer. Ten microliters of 4xSDS-PAGE sample buffer and 5 μl 1 M dithiothreitol were added to the pellet and the sample was boiled for 5 minutes and centrifuged. The supernatant was saved for SDS-PAGE. Fifty micrograms of protein lysate was subjected to SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and transferred to PVDF membranes. Blots were blocked in 5% milk solution and exposed to anti-mouse first antibodies overnight at 4°C. First antibodies were reacted with horse radish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies. All membranes were visualized using West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Gel-Pro Analyzer software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD) was used to quantify the bands obtained via Western Blotting. The ban optical density was normalized to the optical density of the loading control band.

Reagents for immunoprecipitation, Western blot analysis and flow cytometry

Antibodies for caspace-3, caspace-9, Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, phospho-SAPK/JNK (T183/Y185), and SAPK/JNK were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA). Monoclonal anti-human/mouse cIAP-2, XIAP, phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CXCR2, and phycoerythrin-labeled rat IgG2a were purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). GAPDH, NF-KB p65, NF-KB p52, anti-phosphoserine, horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA).

Hepatocyte Isolation

Primary hepatocytes were isolated by collagenase perfusion. Anesthesia was induced with isoflurane inhalation, laparotomy performed, and the inferior vena cava cannulated with a 26-gauge angiocatheter. Liver perfusion buffer (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) was used to flush the liver of intravascular blood (3 ml/minute for 10 minutes). This was followed by infusion of liver digest buffer (GIBCO, 3 ml/minute for 10 minutes). The liver was excise from the animal, placed in a petri dish, minced into 1-mm pieces, and gently agitated to disperse the cells in wash buffer (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY). The cell suspension was filtered and washed two times at 50g at 4°C for 5 minutes. Cells were immediately used for RT-PCR or flow cytometry.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription PCR

Hepatocytes were isolated as described above. Mouse neutrophils were isolated from the pooled blood of three mice by differential gradient centrifugation over Percol (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY). Total RNA from hepatocytes or neutrophils was isolated with RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to manufacture’s instruction. The PCR primers were designed using software Primer Premier (PREMIER Biosoft International) to cross exon1 and exon2. Sense primer: 5′-TGCTCACAAACAGCGTCGTA-3′. Anti-sense primer: 5′-TCAGGGCAAAGAACAGGTCA-3′.

Reverse transcription was performed using with QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). The extracted RNA was on-column DNase digested (RNase-free DNase set, Qiagen) and 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with QuantiTech Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). Real-time PCR was performed in a SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using Bio-Rad iCycler iQ Multicolor Real-Time PCR Detection System using the following protocol: initial activation at 95°C for 15 minutes, 40 cycles at 94°C for 15 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds and 72°C for 30 seconds. Amplification specificity was checked by melting curve analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis.

Flow cytometry

Hepatocytes were harvested and immediately studied with flow cytometry for CXCR2 expression. Cells were washed twice in staining buffer (DIFCO, Detroit, MI), resuspended in 100 μL of staining buffer, incubated for 15 minutes at 4 °C with anti-mouse CD16/32 to block Fc receptors, and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CXCR2 or phycoerythrin-labeled rat IgG2a. Final antibody concentrations were 1 to 2 μg/100 μl cell solution. After incubation, cells were washed twice in staining buffer, and analyzed. Flow cytometry was performed using a FACScan cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). Data were collected and analyzed using CellQuest software. A minimum of 10,000 cells was analyzed to determine cell-surface CXCR2 expression.

ELISA

Fifty mg of mouse liver was homogenized in one ml lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors. Protein concentration was measured and the samples were adjusted to same protein concentrations. KC and MIP2 were measured using Quantikine Murine ELISA kits (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacture’s instruction. The KC and MIP2 concentrations were calculated per gram of liver protein.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean±SEM. Statistical calculations were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA) on a Macintosh PowerBook G4 computer. Statistical analysis was performed using an upaired Student’s t-test or two-way ANOVA. Differences were considered significant if p< 0.05. Survival rates are presented using Kaplan-Meier curves, and significance was calculated by the log rank test.

Results

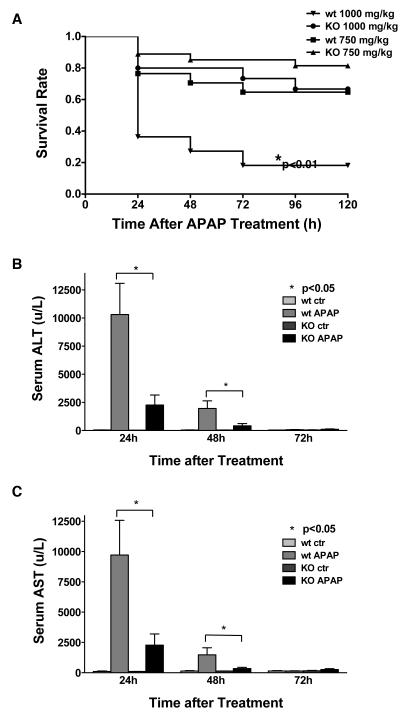

CXCR2 knock out mice treated with APAP have a lower mortality than wild type mice

Wild type (n=17) and knock out mice (n=27) mice received 750 mg/kg APAP; mortality was recorded every 24 hours out to 5 days. Although CXCR2 wild type mice had a higher mortality than CXCR2 knock out mice, this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1). Although previous experiments have suggested that 750 mg/kg APAP is an LD50 dose, neither group in this study reached this mortality rate and this is likely why the differences seen did not reach statistical significance. Therefore, additional wild type (n=11) and knock out (n=15) mice were treated with 1000 mg/kg APAP and mortality was measured every 24 hours out to five days. At this increased APAP dose, wild type mice mortality was significantly higher than CXCR2 knock out mice (Figure 1A, p<0.01).

Figure 1.

Panel A: The mortality rate of CXCR2 knock out mice versus wild type mice after intraperitoneal administration of 750 mg/kg or 1000 mg/kg APAP is shown. The number of surviving animals was measured every 24 hours out to 5 days. The survival curves were generated using Kaplan-Meier Analysis. (* p<0.01 versus knock out animals receiving the same APAP dose). Panel B and C: Serum ALT (Panel B) and AST (Panel C) in CXCR2 knock out and wild type mice treated with 375 mg/kg APAP or PBS (control). Serum was collected at 24, 48, and 72 hours and serum ALT (Panel A) and AST (Panel B) activities were determined (n≥5/group). CXCR2 knock out mice had significantly lower ALT and AST levels at 24 and 48 hours (p<0.05), as compared to wild type mice.

Serum AST and ALT are lower in CXCR2 knock out mice as compared to wild type mice after APAP

Since APAP is a hepatoxic agent, serum AST (Figure 1B) and ALT (Figure 1C) were measured in knock out and wild type mice after APAP or PBS administration. AST and ALT peaked at 24 hours, returned to base line at 72 hours and were significantly lower in CXCR2 knock out mice versus wild type mice at 24 and 48 hours. This suggests that APAP treatment in CXCR2 knock out mice causes less liver injury than in wild type mice, providing some explanation for the lower mortality rate in knock out mice.

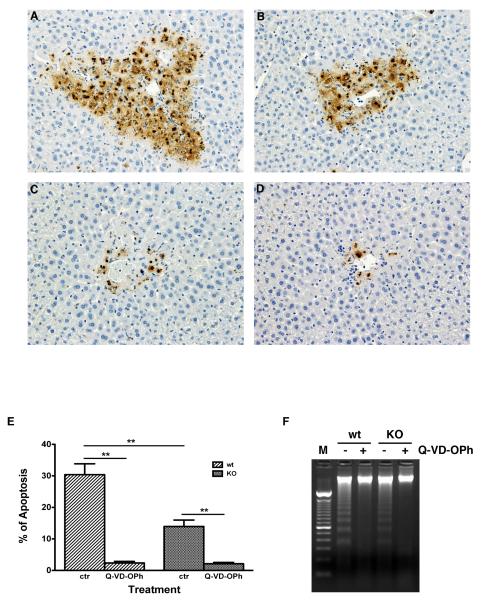

Less hepatocyte apoptosis was seen after APAP in CXCR2 knock out versus wild type mice

Liver injury was also investigated by measuring hepatocyte apoptosis with TUNEL staining and DNA fragmentation analysis. Less apoptosis was seen 16 hours following APAP in CXCR2 knock out mice (Figure 2A and 2B) versus wild type mice. The percentage of hepatocyte apoptosis in CXCR2 knock out mice (n=9, 13.95±2.03%) was significantly lower than in wild type mice (n=9, 30.39±3.45%, Figure 2E, p<0.01). Thus, less apoptosis in CXCR2 knockout mice after APAP may be a possible mechanism for the lower mortality rate after lethal APAP dosing in CXCR2 knockout mice. To verify that apoptosis was important in this liver injury, additional mice received Q-VD-OPh. TUNEL staining demonstrated significantly less hepatocyte apoptosis in both wild type (2.37±0.5%, n=6) and knock out mice ((2.13± 0.41%, n=6, Figure 2C, 2D and 2E) receiving this caspace inhibitor and APAP. DNA fragmentation studies confirmed this finding (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

Wild type mice (Figure 2A & 2C) and CXCR2 knock out mice (Figure 2B &2D) were treated with 375 mg/kg APAP, with (Figure 2C & 2D) or without (Figure 2A & 2B) treatment with the pan-caspace inhibitor, Q-VD-OPh, sacrificed at 16 hours, and hepatocyte apoptosis assessed by TUNEL staining (400X). TUNEL positive cells were counted and the percentage of positive cells are illustrated in Figure 2E (**p<0.01, n=6-9 mice/group). DNA fragmentation is shown on Figure 2F and confirms the TUNEL staining findings. (Lane M: DNA molecular marker control). The percentage of hepatocyte apoptosis in CXCR2 knock out mice (n=9, 13.95±2.03%) was significantly lower than in wild type mice (n=9, 30.39±3.45%, Figure 2E, **p<0.01); these animals did not receive any pretreatment with Q-VD-OPh. This suggests that a decrease in apoptosis in CXCR2 knockout mice in response to APAP toxicity may be one of the mechanisms responsible for the decrease in mortality rate after lethal APAP dosing in CXCR2 knockout versus wild type mice. To verify that apoptosis was playing a significant role in the liver injury in this model, additional mice received 50 mg/kg of the pan-caspace inhibitor, Q-VD-OPh, in addition to APAP. TUNEL staining demonstrated significantly less apoptosis in the livers of both wild type (Figure 2C) and knock out mice (Figure 2D) receiving the caspace inhibitor with APAP. TUNEL positive cells were significantly decreased in both wild type (2.37±0.5%, n=6) and knockout mice livers (2.13± 0.41%, n=6) for animals receiving Q-VD-OPh and APAP, as compared to animals receiving APAP alone (Figure 2E). DNA fragmentation studies confirmed these findings (Figure 2F).

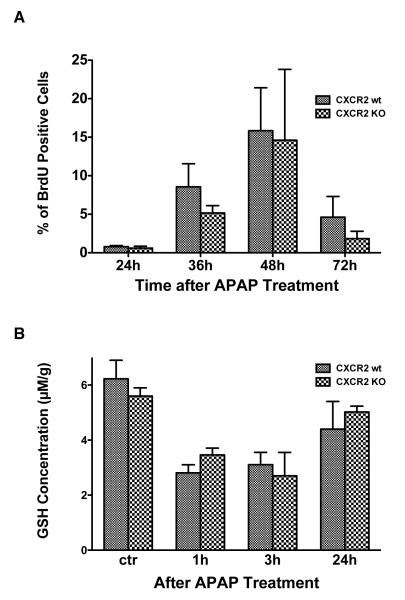

There is no difference in hepatocyte proliferation between CXCR2 knock out and wild type mice after APAP

To determine whether differences in hepatocyte proliferation between wild type and knock out mice might account for the differences observed in mortality, hepatocyte proliferation after APAP was measured by hepatocyte BrdU incorporation (Figure 3A). BrdU incorporation peaked at 48 hours in both groups. Although wild type mice had a slightly higher hepatocyte proliferation rate as compared to knock outs, this did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 3.

Panel A: In vivo hepatocyte proliferation after APAP treatment in CXCR2 knock out and wild type mice was measured via BrdU incorporation at various time points (n≥4/group). Although wild type mice had a slightly higher proliferation rate at all time points, none of these differences achieved statistical significance. Panel B: Liver glutathione levels were measured after APAP treatment in wild type and CXCR2 knock out mice (n=4-8 mice/group); no differences in glutathione levels were detected between the two groups.

There is no difference in hepatic glutathione depletion in CXCR2 knock out versus wild type mice after APAP

To investigate whether CXCR2 signaling affects APAP metabolism, we measured hepatic glutathione concentration in wild type and CXCR2 knock out mice after 375 mg/kg APAP at different time points (Figure 3B). Glutathione concentrations decreased within one hour of APAP administration and began to rebound within 24 hours. No significant differences were seen in hepatic glutathione concentrations in wild type versus CXCR2 knock out mice, suggesting that CXCR2 signaling does not affect APAP metabolism.

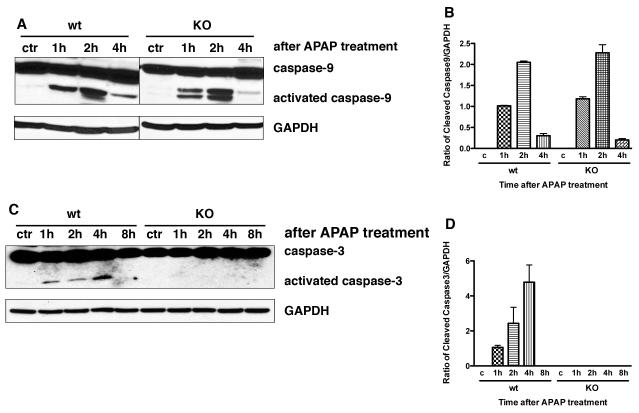

APAP treatment causes hepatic caspase-3 and caspase-9 activation

Apoptosis is dependent on caspase activation. Because there is less apoptosis after APAP toxicity in knock out versus wild type mice, we examined hepatic caspase-3 and caspase-9 activity at 1, 2, 4, and 8 hours after APAP administration. Using Western blot analysis, hepatic caspase-3 and caspase-9 were activated in both wild type and CXCR2 knock out mice within one hour of APAP (Figure 4). Although no differences were seen in activated caspase-9 between knock out and wild type mice (Figure 4A and 4B), activated hepatic caspace-3 levels were undetectable in knock out mice as compare to obvious levels in wild type mice (Figure 4C and 4D, p<0.05 at all time points).

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis for activated hepatic caspase-3 and caspase-9 1, 2, 4, and 8 hours after APAP treatment in wild type and CXCR2 knock out mice. Panel A and B demonstrate activated caspase-9 and Panel C and D demonstrate activated caspase-3. There were no differences in activated caspace-9 between wild type and knock out mice; in contrast, there were significant differences between levels of activated caspace-3 at all time points in wild type versus CXCR2 knock out mice (p<0.05 for all time points). GAPDH levels demonstrate equal loading of the gels. Experiments were performed at least three times with similar results.

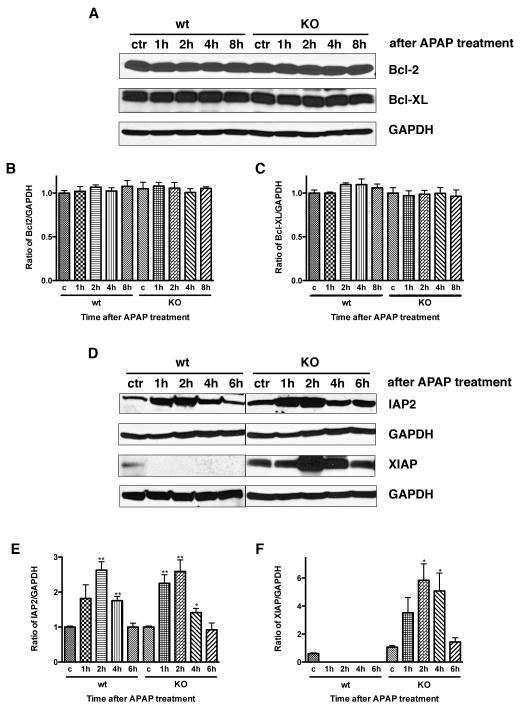

XIAP is increased in CXCR2 knock out mice after acetaminophen administration

Since there is a difference in apoptosis after APAP dosing in CXCR2 knock out mice versus wild type controls, as well as differences in caspase-3 activation, we next investigated if there were differences in prosurvival protein expression after APAP administration. Western blotting for the antiapoptotic proteins cIAP-2, XIAP, Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL was performed on hepatic tissues 1, 2, 4, and 6 or 8 hours after APAP administration. There were no differences in hepatic Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL expression (Figure 5A, 5B, and 5C). In contrast, cIAP2 expression increased in wild type and CXCR2 knock out mice after APAP, with significant increases seen within 1-2 hours of APAP dosing; levels decreased to baseline by 6 hours post-APAP (Figure 5D and 5E). While significant cIAP increases were seen in wild type and CXCR2 knock out mice relative to control animals, there were no significant differences in cIAP levels in wild type versus knock out mice at any time point. XIAP demonstrated the most significant differences in survival protein expression. Wild type mice expressed minimal XIAP in response to APAP. In contrast, significant hepatic XIAP expression was seen after APAP in CXCR2 knock out mice (Figure 5D and 5F, p<0.01 at 2 and 4 hours).

Figure 5.

Representative Western blots showing hepatic expression of prosurvival proteins in CXCR2 knock out mice and wild type controls treated with APAP. Panels A, B, and C demonstrate Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL protein levels and show no change in response to APAP dosing in wild type or CXCR2 knock out mice. In contrast, Panels D, E, and F illustrate hepatic cIAP2 and XIAP protein levels and these do show differences in response to APAP. cIAP2 levels increase in both wild type and CXCR2 knock out mice in response to APAP; wild type levels are significantly different from controls at 2 and 4 hours (**p<0.01) and knock out levels are significantly different from controls at 2, 4, and 6 hours (*p<0.05 and **p<0.01). However, there were no significant differences between wild types and knock outs at any time point. In contrast, significant increases in XIAP levels in CXCR2 knock out mice are seen in response to APAP, while no increases in XIAP are seen in response to APAP in wild type mice (**p<0.01). GAPDH levels are shown to demonstrate equal loading of the gels. Experiments were performed at least three times with similar results.

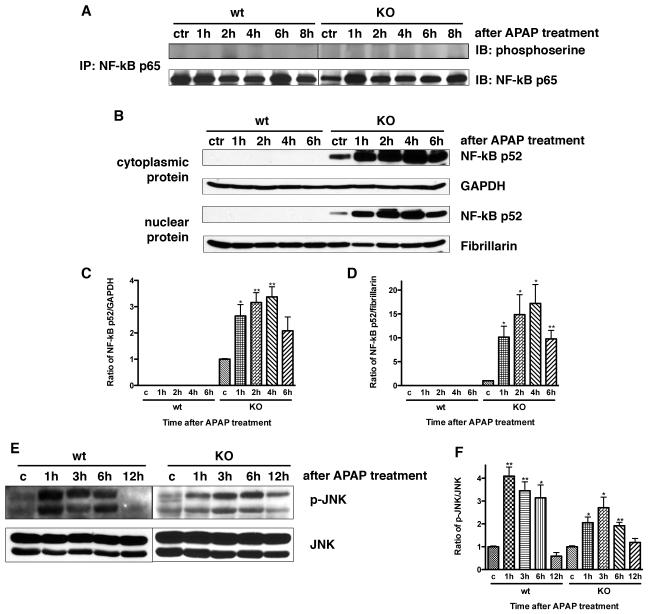

Hepatic NF-κB p52 is activated in CXCR2 knock out mice after APAP administration

XIAP upregulation is controlled by activation of NF-κB p65 and p52 (11,12). To investigate if hepatic NF-κB p65 was activated in mice after acetaminophen administration, we measured phosphorylated NF-κB p65 using immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting at various time points after APAP dosing. There was no evidence of activated hepatic NF-κB p65 in wild type or CXCR2 knock out mice after APAP (Figure 6A). Next, we measured hepatic cytoplasmic and nuclear NF-κB p52 in knock out or wild type mice after APAP. There was significant NF-κB p52 expression in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear hepatic proteins from CXCR2 knock out mice treated with APAP. There was no detectable hepatic NF-κB p52 after APAP in wild type mice (Figure 6B, 6C, and 6D).

Figure 6.

Activated NF-κB p65 was measured by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting in liver tissues at various time points after APAP administration (Panel A); no changes were seen in response to APAP at any time point in either wild type or knock out mice. Next, hepatic cytoplasmic (Panel B and C) and nuclear (Panel B and D) proteins were extracted and NF-κB p52 expression was examined at various time points after APAP dosing with Western blot. This demonstrated that hepatic NF-κB p52 is activated in CXCR2 knock out mice in both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments after APAP administration and was not detectable in either the cytoplasmic or nuclear proteins in wild type mice after APAP (*p<0.05 and **p<0.01 vs wild type mice at the same time point and also compared to their respective controls). GAPDH was used as cytoplasmic protein loading control and fibrillarin was used as nuclear protein control. Next, activated hepatic JNK was measured by Western blotting in wild type and CXCR2 knock out mice in response to APAP (Panel E and F). JNK levels increased significantly in response to APAP in both CXCR2 knock out mice as well as wild type mice (*p<0.05 and **p<0.01 vs their respective controls). CXCR2 knock out mice have less activated hepatic JNK after APAP as compared to wild type mice, and this reach statistical significance at the one hour time point (p<0.05). Experiments were performed three times with similar results.

APAP induces hepatic JNK activation in wild type and CXCR2 knock out mice

We examined hepatic JNK expression in wild type and CXCR2 knock out mice following 375 mg/kg APAP to investigate whether CXCR2 signaling causes JNK activation. CXCR2 knock out and wild type mice had a significant JNK increase after APAP. Hepatic JNK activation in wild types peaked 1 hour after APAP administration, gradually declined, and returned to baseline at 12 hours; JNK activation in CXCR2 knock out mice was slower and weaker than wild type mice (Figure 6E and F). Less JNK activation was seen in CXCR2 knock out versus wild type mice; this was statistically significant at one hour (p<0.05).

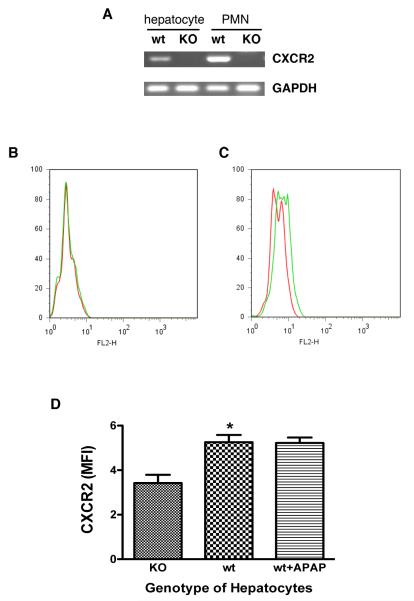

CXCR2 expression on mouse hepatocytes

To determine whether the effects of CXCR2 signaling occurs directly within hepatocytes, as opposed to an indirect effect on other cell types within the liver, we measured CXCR2 expression on primary mouse hepatocytes; we utilized mouse neutrophils as a positive control, as these cells are well known to express CXCR2. RT-PCR was performed using a pair of primers located in exon2 (data not shown). These experiments confirmed CXCR2 expression on wild type hepatocytes and neutrophils and no CXCR2 expression on CXCR2 knock out hepatocytes and neutrophils (data not shown). To exclude the possibility of contamination by genomic DNA, we designed a second pair of primers that crossed exon1 and exon2. These experiments confirmed that wild type hepatocytes and neutrophils express CXCR2 (Figure 7A); CXCR2 knock out hepatocytes did not express any detectable CXCR2.

Figure 7.

Panel A demonstrates RT-PCR for CXCR2. Wild type hepatocytes and neutrophils demonstrate obvious levels of CXCR2, while there are no detectable levels for hepatocytes or neutrophils from the CXCR2 knock out mice. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Panel B illustrates flow cytometry for cells expressing CXCR2. The cells were stained with phycoerythrin conjugated isotype IgG (red line) or CXCR2 (green line). Representative histograms are shown for CXCR2 expression on knock out mouse hepatocytes (Panel B) and wild type mouse hepatocytes (Panel C). Panel D illustrates quantitative CXCR2 expression using flow cytometric analysis by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). (n=6-12 mice/group, *p=0.0015). Wild type mouse hepatocytes express low levels of CXCR2; this does not change after treatment with APAP.

Flow cytometry confirmed these results (Figure 7B and 7C). Wild type hepatocytes expressed low CXCR2 levels. There was no CXCR2 expression on knock out mouse hepatocytes. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CXCR2 on wild type hepatocytes (5.26±0.33%) was significantly increased (Figure 7D) versus knock out mouse hepatocytes (3.42±0.37%, p<0.05). MFI of hepatocyte CXCR2 expression in wild type mice 3 hours after APAP dosing was the same as that of untreated hepatocytes, suggesting that APAP treatment does not change hepatocyte CXCR2 expression in wild type mice (Figure 7D).

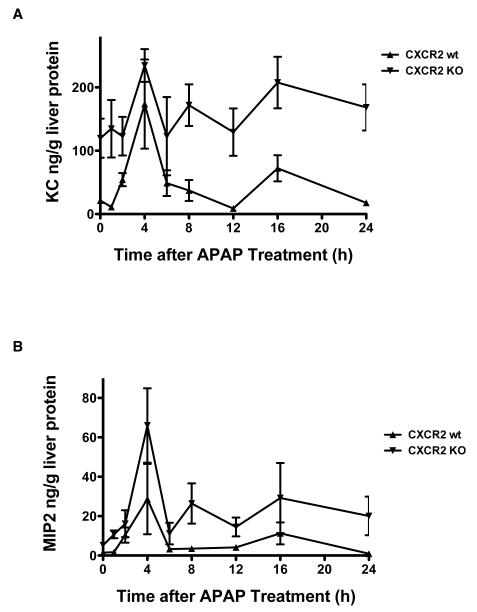

KC and MIP2 expression are increased in CXCR2 knock out mice after acetaminophen administration

Our results suggest that CXCR2 signaling facilitates apoptosis after acetaminophen dosing. CXCR2 activation requires that CXCR2 ligands, which include KC and MIP2, bind to this receptor. We hypothesized that acetaminophen increases KC and MIP2 production, so hepatic KC and MIP2 protein expression was measured in wild type and knock out mice after APAP administration by ELISA (Figure 8A and 8B). KC and MIP2 protein levels increased after acetaminophen, peaking at 4 hours in both wild type and knock out mice. KC and MIP2 levels in the CXCR2 knock out mice were significantly higher than wild type mice (p<0.01) at every time point.

Figure 8.

Acetaminophen increased hepatic KC and MIP2 protein production in both wild type and knock out mice (n=4-8 mice/group/time point). Panel A illustrates KC levels, Panel B demonstrates MIP2 levels. CXCR2 knock out mice have significantly increased levels of each chemokine as compared to wild type controls at all time points (p<0.01).

Discussion

These experiments show that CXCR2 knock out mice have a survival advantage over wild type mice after an LD50 acetaminophen dose. The liver injury following acetaminophen in CXCR2 knock out mice is less than seen in wild type mice, resulting in significantly lower levels of serum liver enzymes and less liver injury. Further experiments suggest that this is at least partially related to less apoptosis in knock out mice versus control animals, with no differences in hepatocyte proliferation. However, the role of apoptosis in acetaminophen-induced liver injury is controversial and it is possible that the less profound GSH depletion seen in this strain of mouse may allow apoptosis to proceed in a more significant fashion than that seen in other models. While the CXCR2 receptor and its ligands, the CXC chemokines, are known to mediate the inflammatory response, these ligand/receptor interactions also modulate proliferation. For example, Bone-Larson and colleagues demonstrated increased hepatocyte proliferation after APAP-injury, which was a CXCR2-dependent response (5). This beneficial proliferative response is dependent on increased CXCR2 expression (5). The CXC chemokines also have a therapeutic role in APAP-induced liver injury (5-7). This conflicts with our study, which suggests the lack of CXCR2 receptor/ligand interaction confers a survival benefit due to a decrease in liver injury from acetaminophen toxicity.

Investigators have shown similar findings to ours in an ischemia/reperfusion model of injury (13). Kuboki and others demonstrated that CXCR2 knock out mice had significantly less liver injury after ischemia/reperfusion, related to accelerated hepatocyte proliferation in the knock out mice (13). This was associated with increased NF-KB and signal transducers and activators of transcription-3 activation and was not associated with changes in inflammation (13). These investigations suggested that low MIP-2 concentrations protected against cell death, whereas high MIP-2 concentrations induced cell death; these effects were absent in the CXCR2 knock out mice (13). Similarly, Ishida and colleagues also demonstrated that CXCR2 knock out mice had a lower mortality rate after APAP injury as compared to control mice, but a higher mortality as compared to neutropenic mice (14). These findings are similar to ours in that the CXCR2 knock out genotype confers protection against a hepatic injury. Our experiments did not demonstrate differences in hepatocyte proliferation, although there were significant decreases in cellular death, and the NF-KB pathway appeared to be involved in this process. Our experiments confirm the presence of the CXCR2 receptor on hepatoctyes in the wild type mice. The CXCR2 ligands, MIP2 and KC, were significantly increased after acetaminophen in both wild type and CXCR2 knock out mice, with the most significant increases seen in the knock out animals. The increased levels in the knock out animals did not appear to have any detrimental hepatic effects, similar to the results of Kuboki and colleagues (13).

Our experiments suggest that the survival advantage conferred by the CXCR2 knock out genotype is related to decreased hepatocyte apoptosis. This is confirmed by a decrease in activated caspace-3, and increases in the prosurvival protein, XIAP, in CXCR2 knock out mice, providing a potential mechanism for decreased apoptosis. The IAP family of proteins protect against apoptosis in many systems, and this is linked to the BIF domains of these molecules binding to and inhibiting caspaces (3). In our model, this links the decrease in activated caspace-3 to the increased XIAP levels in the knock out mice. XIAP is known to potently inhibit caspaces-3, -7, and -9, also correlating with our data (15).

Another mechanism for XIAP-conferred protection against apoptosis is from a positive feedback mechanism where XIAP induces NF-KB, with additional recruitment of other target genes (4). XIAP, as well as cIAP, can activate NF-KB. cIAP is also upregulated in our model, although this was seen in wild type and knock out mice, so it does not provide as much of a clear explanation of the differences in these two genotypes (4). Another interesting aspect regarding XIAP effects was demonstrated by Levkau and colleagues, who showed that XIAP overexpression inhibited cell proliferation; this may suppress the cell cycle and prevent cells from exiting G0/G1 into phases of the cell cycle that are more vulnerable to apoptotic signals (3).

While the classical NF-KB activation pathway is important in many cellular processes, the “non-canonical” NF-KB pathway is also important for normal and pathological processes. NF-KB is restricted to the cytoplasm by inhibitory proteins that are degraded when specifically phosphorylated, permitting NF-KB to enter the nucleus and activate target genes. Different combinations of NF-KB subunits induce transcription with different timing sequences and recognize different sequences of NF-KB binding sites. The non-canonical pathway is based on processing of the NF-KB2 gene product, p100 (11,12). The p52 subunit is generated from p100 processing by IKKalpha, one of the kinase complexes (11,12). Once produced, p52 can enter the nucleus and induce genes that regulate many processes (12). In other systems, including androgen sensitive LNCaP cells in vitro and lymphoma cells, NF-KB/p52 encourages cellular growth by protecting cells from apoptosis, as well as stimulating cyclin D1 expression (16,17). Coculture of bone marrow stromal cells with lymphoma cells resulted in active p52 generation, which then translocates to the nucleus, and is associated with increased XIAP and cIAP expression, similar to what is seen in our system (17).

Investigators have shown a significant relationship between NF-KB, XIAP and the c-Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) cascade (18-20). Bubici and colleagues have shown that NF-KB-mediated apoptosis suppression involves inhibition of the JNK cascade, which is related to upregulation of a variety of mediators, including XIAP, which block aspects of the JNK cascade (18). Similarly, Kaur and colleagues have shown that XIAP inhibits JNK activation by transforming growth factor β1, counteracting TGF-β1-induced apoptosis (20). This is consistent with our findings, in which CXCR2 knock out mice have increased XIAP levels, decreased JNK levels, and decreased apoptosis and mortality. Other investigators have used leflunomide with APAP toxicity and have shown a protective effect that as due to inhibition of APAP-induced JNK activation. This decreased Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL activation and decreased apoptosis (19). This is also consistent with our studies. In contrast, other investigators have shown that that acetaminophen-induced activation of JNK promotes necrosis by a direct effect on mitochondria (21,22).

References

- 1.Sakil AO, Kramer D, Mazariegos GV, Fung JJ, Rakela J. Acute liver failure: Clinical features, outcome analysis and applicability of prognostic criteria. J Liver Transpl. 2000;6:163–169. doi: 10.1002/lt.500060218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahlin DC, Miwa GT, Lu AY, Nelson SD. N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine: a cytochrome P-450-mediated oxidation product of acetaminophen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1327–1331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levkau B, Garton KJ, Ferri N, Kloke K, Nofer JR, Baba HA, Raines EW, Breithardt G. xIAP induces cell-cycle arrest and activates nuclear factor-KB. New survival pathways disabled by caspace-mediated cleavage during apoptosis of human endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2001;88:282–290. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu ZL, McKinsey TA, Liu L, Gentry JJ, Malim MH, Ballard DW. Suppression of tumor necrosis factor-induced cell death by inhibitor or apoptosis, c-IAP is under NF-KB control. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:10057–10062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bone-Larson CL, Hogaboam CM, Evanhoff H, Strieter RM, Kunkel SL. IFN-gamma-inducible protein-10 (CXCL10) is hepatoprotective during acute liver injury though induction of CXCR2 on hepatocytes. J Immunol. 2001;167:7077–7083. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.7077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogaboam CM, Bone-Larson CL, Steinhauser ML, Lukas NW, Colletti LM, Simpson KJ, Strieter RM, Kunkel SL. Novel CXCR2-dependent liver regenerative qualities of ELR containing CXC chemokines. FASEB. 1999;13:1565–1574. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.12.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren X, Carpenter A, Hogaboam C, Colletti L. Mitogenic properties of endogenous and pharmacologic doses of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 after 70% hepatectomy in the mouse. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:563–570. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63684-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefanovic L, Brenner DA, Stefanovic B. Direct hepatotoxic effect of KC chemokine in the liver without infiltration of neutrophils. Exp Biol Med. 2005;230:573–586. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kofman AV, Morgan G, Kirschenbaum A, Osbeck J, Hussain M, Swenson S, Theise ND. Dose- and time-dependent oval cell reaction in acetaminophen-induced murine liver injury. Hepatology. 2005;41:1252–1261. doi: 10.1002/hep.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caserta TM, Smith AN, Gultice AD, Reedy MA, Brown TL. Q-VD-OPh, a broad spectrum caspace inhibitor with potent antiapoptotic properties. Apoptosis. 2003;8:345–352. doi: 10.1023/a:1024116916932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wietek C, Cleaver CS, Ludbrook V, Wilde J, white J, Bell DJ, Lee M, Dickson M, Kay KP, O’neill LA. IkappaB kinase epsilon interacts with p52 and promotes transactivation via p65. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34973–34981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao G, Rabson AB, Young W, Qing G, Qu Z. Alternative pathways of NF-kappaB activation: a double-edged sword in health and disease. Cytokine and Growth Factor Reviews. 2006;17:281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuboki S, Shin T, Huber N, Eismann T, Galloway E, Schuster R, Blanchard J, Edwards MJ, Lentsch AB. Hepatocyte signaling through CXC chemokine receptor-2 is detrimental to liver recovery after ischemia/reperfusion in mice. Hepatology. 2008;48:1213–1223. doi: 10.1002/hep.22471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishida Y, Kondo T, Kimura A, Tsuneyama K, Takayasu T, Mukaida N. Opposite roles of neutrophils and macrophages in the pathogenesis of acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1028–1038. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deverauz QL, Roy N, Stennicke HR, Van Arsdale T, Zhou Q, Srinivasula SM, Alnemri ES, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. IAPs block apoptotic events induced by caspace-8 and cytochrome c by direct inhibition of distinct caspaces. EMBO J. 1998;17:2215–2223. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nadiminty N, Chun JY, Lou W, Lin X, Gao AC. NF-kappaB2/p52 enhances androgen-independent growth of human LNCaP cells via protection from apoptotic cell death and cell cycle arrest induced by androgen-deprivation. Prostate. 2008;68:1725–1733. doi: 10.1002/pros.20839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lwin T, Hazlehurst LA, Li Z, Dessureault S, Sotomayor E, Moscinski LC, Dalton WS, Tao J. Bone marrow stromal cells prevent apoptosis of lymphoma cells by upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins associated with activation of NF-kappaB(RelB/p52) in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cells. Leukemia. 2007;21:1521–1531. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bubcic C, Papa S, Pham CG, Zazzeroni F, Franzoso G. NF-KB and JNK. An intricate affair. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:1524–1529. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.12.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latchoumycandane C, Goh CW, Ong MMK, Boelsterli UA. Mitochondrial protection by the JNK inhibitor Leflunomide rescues mice from acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2007;45:412–421. doi: 10.1002/hep.21475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaur S, Wang F, Venkatraman M, Arsura M. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) inhibits c-jun-N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1) activation by transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) through ubiquitin-mediated proteosomal degradation of the TGF-β1-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38599–38608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505671200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunawan BK, Liu ZX, Han D, Hanawa N, Gaarde WA, Kaplowitz N. c-Jun N-terminal kinase plays a major role in murine acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Gastroenterol. 2006;131:165–178. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanawa H, Shinohara M, Saberi B, Gaarde WA, Han D, Kaplowitz H. Role of JNK translocation to mitochondira leading to inhibition of mitochondrial bioenergetics in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13565–13577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708916200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]