Abstract

Concentrated erythrocyte (i.e., red blood cell) suspensions flowing in microchannels have been simulated with an immersed-boundary lattice Boltzmann algorithm, to examine the cell layer development process and the effects of cell deformability and aggregation on hemodynamic and hemorheological behaviors. The cells are modeled as two-dimensional deformable biconcave capsules and experimentally measured cell properties have been utilized. The aggregation among cells is modeled by a Morse potential. The flow development process demonstrates how red blood cells migrate away from the boundary toward the channel center, while the suspending plasma fluid is displaced to the cell free layer regions left by the migrating cells. Several important characteristics of microscopic blood flows observed experimentally have been well reproduced in our model, including the cell free layer, blunt velocity profile, changes in apparent viscosity, and the Fahraeus effect. We found that the cell free layer thickness increases with both cell deformability and aggregation strength. Due to the opposing effects of the cell free layer lubrication and the high viscosity of cell-concentrated core, the influence of aggregation is complex but. The lubrication effect appears to dominate, causing the relative apparent viscosity to decrease with aggregation. It appears therefore that the immersed-boundary lattice Boltzmann numerical model may be useful in providing valuable information on microscopic blood flows in various microcirculation situations.

Keywords: Red Blood Cells, Blood Flows, Cell Free Layer, Microcirculation, Hemodynamics, Hemorheology, Lattice Boltzmann Method, Immersed Boundary Method

I. INTRODUCTION

Erythrocytes (i.e., red blood cells, RBCs) are an important determinant of the rheological properties of blood because of their large number density (~ 5 × 106/mm3), particular mechanical properties, and aggregation tendency. Typically, a human RBC has a biconcave shape of ~ 8 μm in diameter and ~ 2 μm in thickness, and is highly deformable [1, 2]. The interior fluid (cytoplasm) has a viscosity of 6 cP, which is about 5 times of that of the suspending plasma (~ 1.2 cP). At low shear stress, RBCs can also aggregate and form one-dimensional stacks-of-coins-like rouleaux or three-dimensional (3D) aggregates [1, 3, 4]. The process is reversible and particularly important in the microcirculation, since such rouleaux or aggregates can dramatically increase effective blood viscosity. RBCs may also exhibit reduced deformability and stronger aggregation in many pathological situations, such as heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, malaria, and sickle cell anemia [1]. The underlying mechanism of RBC aggregation is still under debate [1, 4].

As a consequence of red cell size, the nature of blood flow changes greatly with the vessel diameter. In vessels larger than 200 μm, the blood flow can be accurately modeled as a homogeneous fluid. However, in vessels smaller than this, such as arterioles and venules, and especially capillaries (4–10 μm, i.d.), the RBCs have to be treated as discrete fluid capsules suspended in the plasma. When flowing in microvessels, the flexible RBCs migrate toward the vessel central region, resulting in a RBC concentrated core in the center, and a cell free layer (CFL) is developed near the vessel wall. Such phenomena are important in microcirculation since they are closely related to the flow resistance and biological transport [1]. Traditionally, to incorporate the CFL effects, microscopic blood flows are modeled as multiphase flows with an interface between the peripheral CFL and the RBC concentrated core [5]. Using such an approach, it is difficult to incorporate the effects of cell properties on hemodynamics and it is not suitable for investigation of the microscopic flow structures.

Benefiting from advances in computer and simulation technologies, now it is possible to model individual RBCs as discrete particles suspended in the plasma media. For example, Pozrikidis and coworkers [6–8] have employed the boundary integral method for Stokes flows to investigate RBC deformation and motion in shear and channel flows; Eggleton and Popel [9] have combined the immersed boundary method (IBM) [10] with a finite element treatment of the RBC membrane to simulate large 3D RBC deformations in shear flow. Recently, a lattice Boltzmann approach has also been adopted for RBC flows in microvessels, where the RBCs were represented as two-dimensional (2D) rigid particles [11]. Bagchi [12] has simulated a large RBC population in vessels of size 20–300 μm. However, RBC aggregation, which has been demonstrated experimentally as an important factor in determining hemodynamic and hemorheological behaviors in microcirculation [1, 3, 13], was not considered in these studies. Liu et al. [14] modeled the intercellular interactions using a Morse potential, thus accounting for RBC aggregation. The cell membrane was modeled with 3D elastic finite elements. Therefore the empirical RBC membrane constitutive relationships, which assume the membrane is a 2D sheet, cannot be utilized directly. Bagchi et al. [15] have extended the IBM approach of Eggleton and Popel [9] to two-cell systems and introduced the intercellular interaction using a ligand-receptor binding model. For rigid particles, Chung et al. [16] have studied the behavior of two rigid elliptical particles in a channel flow utilizing the theoretical formulation of depletion energy proposed by Neu and Meiselman [17]. It has been noted that such a description yields a constant (instead of a decaying) attractive force with large separations, which is not physically realistic [16]. Sun and Munn [18] have also improved their lattice Boltzmann model by including an interaction force between rigid RBCs.

Recently, we have developed an integrated model to study RBC behaviors in both shear and channel flows [19, 20]. This model combines the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) for fluid flows and IBM for the fluid-membrane interaction. Crucial factors, including the membrane deformability, viscosity difference across the RBC membrane, and intercellular aggregation, have been carefully considered in the model. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of different RBC deformabilities and aggregation strengths on CFL structure and flow resistance in microscopic blood flows. We also explored the process of RBC flow development upon the application of an external pressure gradient. Finally, our results are also compared to previous experimental observations and numerical simulations.

II. MODEL AND METHODS

A. RBC Model

The undeformed human RBC has a biconcave shape as described by the following equation [21]:

| (1) |

where c0= 0.207, c1= 2.002, and c2= 1.122. The non-dimensional coordinates (x̄, ȳ) are normalized by the radius of a human RBC (3.91 μm). The RBC membrane is a neo-Hookean, highly deformable viscoelastic material with a finite bending resistance that becomes more profound in regions with large curvature [22, 23]. For the 2D RBC model in the present study, following Bagchi et al. [12, 15], the neo-Hookean elastic component of membrane stress can be expressed as

| (2) |

where Es is the membrane elastic modulus and ε is the stretch ratio. In addition, the bending resistance can also be represented by relating the membrane curvature change to the membrane stress with [7, 15]

| (3) |

where Eb is the bending modulus and κ and κ0 are, respectively, the instantaneous and initial stress-free membrane curvatures. l is a measure of the arc length along the membrane surface. Therefore, the total membrane stress T induced as a result of the cell deformation is a sum of the two terms discussed above:

| (4) |

Here n is the local normal direction on the membrane.

Currently, there are two theoretical descriptions of the aggregation mechanism: the bridging model and the depletion model [1, 4]. The former assumes that macromolecules, such as fibrinogen or dextran, can adhere onto the adjacent RBC surfaces and bridge them together [24–26]. The depletion model attributes the RBC aggregation to a polymer depletion layer between RBC surfaces, which is accompanied by a decrease of the osmotic pressure [27, 28]. Detailed discussions of these two models can be found elsewhere (see, for example, a review by Baumler et al. [4]). To incorporate the aggregation, here we modeled the intercellular interaction energy φ as a Morse potential:

| (5) |

where r is the surface separation, r0 and De are, respectively, the zero force separation and surface energy, and β is a scaling factor controlling the interaction decay behavior. The interaction force from such a potential is its negative derivative, i.e., f(r) = −∂φ/∂r. This Morse potential was selected for its simplicity and realistic physical description of the cell-cell interaction; however, it does not imply any particular underlying mechanism. Other aggregation models can be readily incorporated into our algorithm.

B. Simulation Methods

A recently proposed IBM-LBM algorithm [19, 20] was employed in this study. In this model, the fluid dynamics was solved by application of LBM while the fluid-membrane interaction was incorporated using IBM. In addition, the fluid property (viscosity here) also has to be updated dynamically with changing RBC shapes and locations. For this purpose, an index θ was introduced, which is 0 in plasma and 1 in cytoplasm. A detailed description of this numerical scheme is provided in the Appendix.

Simulations were carried out over a 100×300 D2Q9 grid (19.5 μm×58.5 μm) domain with 27 biconcave RBCs (Figure 1a). No-slip and periodic boundary conditions were imposed on the channel surfaces and the inlet/outlet, respectively [29]. The volume conservation of RBCs in our 2D simulations was naturally accomplished in IBM. The actual changes in the enclosed RBC areas were typically less than 1% due to numerical errors. Flow was initiated by a pressure gradient along the channel, using a recently proposed boundary treatment [30]. The applied pressure gradient here is 62.5 kPa/m; such a pressure gradient, according to the Poiseuille law, will generate a mean velocity of 1.65 mm/s for a pure plasma flow with no RBCs. This velocity is in the typical range in microcirculation for microvessels of this size [11, 31].

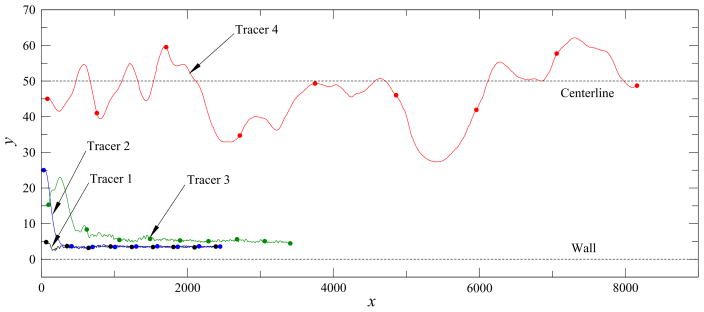

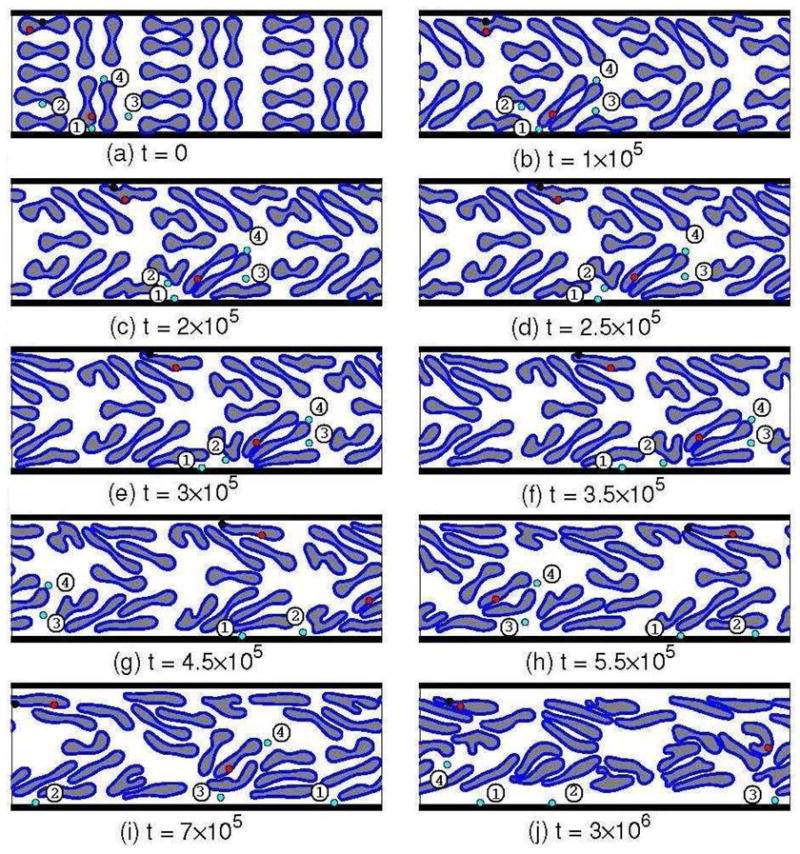

FIG. 1.

Representative snapshots of the flow developing process of normal RBCs with moderate aggregation. The red and blue circles are fluid tracers inside RBCs and in plasma, respectively; and the black circles are a membrane marker on one RBC. The four fluid tracers in plasma (blue circles) have also been labeled for the convenience of discussion. The simulation domain is 19.5×58.5 μm and the time step is 1.25×10−8 s.

The membrane of each RBC was represented by 100 equal-length segments, and the tube hematocrit (HT) in our simulations was 32.2%.. The simulation parameter values are listed in Table I. Experimental values are not available for the parameters in the Morse potential Eq. (5) for the intercellular interaction. The De values utilized for moderate and strong aggregations were selected based on our previous studies [19, 20]. According to Neu and Meiselman [17], the zero force distance r0 is ~ 14 μm. In our simulations, r0 was chosen as 2.5 lattice units (0.49 μm) due to the limitation of the grid size and the immersed boundary treatment. To improve the computational efficiency, as is typical in molecular dynamics simulations, a cut-off distance was also adopted. The scaling factor β was adjusted so that the attractive force beyond the cut-off distance rc = 3.52 μm can be neglected.

TABLE I.

Simulation parameters

| Definition | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| lattice unit | h | 0.195 μm |

| time step | Δt | 1.25×10−8 s |

| fluid density | ρ | 1000 kg/m3 [47] |

| plasma viscosity | μp | 1.2 cP [47] |

| cytoplasm viscosity | μc | 6.0 cP [48] |

| membrane elastic modulus | Es | 6.0×10−6 – 1.2×10−4 N/m [48] |

| membrane bending resistance | Eb | 2.0×10−19 – 4.0×10−18 Nm [48] |

| intercellular interaction strength | De | 0 – 1.3×10−6 μJ/μm2 [20] |

| scaling factor | β | 3.84 μm−1 |

| zero force distance | r0 | 0.49 μm |

To visualize the flow field over a time period, we employed virtual tracers in our simulations. The tracer position xt(t) was updated with time t using the Euler scheme

| (6) |

where Δt is the time step, and u is the fluid velocity. Such tracers serve the purpose of flow visualization and have no influence on simulation results. The volumetric flow rates of the blood suspension Qtotal and of the RBCs QRBC through the channel were calculated from the streamwise velocity u and index θ distributions by

| (7) |

and

| (8) |

respectively. The discharge hematocrit, HD, can also be evaluated from the averaged values of Qtotal and QRBC over a time period when the flow is relatively stable:

| (9) |

In addition, as a measure of the resistance increase due to the RBC existence, the relative apparent viscosity μrel is defined as

| (10) |

where Qp = ΔP H3/12Lμp is the flow rate of a pure plasma flow under the same pressure gradient ΔP/L. Here ΔP is the pressure difference applied across the channel of length L and width H. As we will see in the Results and Discussion section, with the cell migration to the central region, CFLs will be developed near the surfaces. Although this phenomenon have been experimentally observed for many years, the determination of CFL thickness is not trivial, especially in small vessels [32]. Here we define the CFL thickness as the distance from the channel boundary to the θ = 0 position extrapolating downhill from the first two θ ≠ 0 points of the θ profile.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. RBC Migration and Plasma Displacement

Simulation snapshots at 10 representative time steps are shown in Figure 1 for normal RBCs with moderate aggregation. Once the pressure gradient is applied, the suspension begins to flow, accompanied by large cell deformations due to various local flow conditions. Meanwhile, during the flow development, RBCs near the boundaries migrate toward the channel center. As a result, CFLs are formed near the channel boundaries and the central region has a higher RBC concentration (Figure 1j). Also displayed in Figure 1 is a membrane marker (the black circle) showing the tank-treating-like membrane motion as the cell drifts and deforms.

Six representative fluid tracers, two inside RBCs and four in plasma, are displayed in the snapshots in Figure 1. The membrane marker (black circle) and the fluid tracer inside that RBC undergo a tank-treading motion. The four tracers in plasma are labeled as 1 to 4. For tracer 1 initially positioned near the lower boundary, its movement is mainly in the flow direction with small transverse fluctuations. However, tracers 2 and 3, originally between RBCs, are quickly displaced toward the boundary CFL regions by the center-ward migrating RBCs (see Figures 1b–g for tracer 2 and 1e–i for tracer 3). Once the tracers arrive in the CFL regions, they behave very similarly to tracer 1 and move mainly in the flow direction. Tracer 4 is trapped between RBCs in the center region and has never entered the CFL regions during the simulation. Their trajectories are also plotted in Figure 2 to show their different behaviors more clearly. As expected, tracer 4 moves much faster than tracers 1–3 at the periphery., In general, a fluid particle will be displaced to the CFL region by migrating RBCs, unless it is closely surrounded by RBCs. Once a fluid particle reaches the CFL region, it will generally maintain that transverse location as it flows downstream. Although this analysis involves virtual fluid tracers, such results imply that small solid particles in blood will accumulate in CFL regions, as has been observed in experiments with platelets [33].

FIG. 2.

Trajectories of the four plasma tracers in Figure 1. The nine circles on each trajectory curve indicate the simulation time, which are from t =0 to t = 8 ×106 with an interval of 106 time steps (Δt = 1.25 × 10−8 s). The tracer positions are presented in lattice units (h = 0.195 μm).

B. RBC Distribution and Velocity Profiles

A more quantitative analysis for the developing process discussed above can also be performed. Figure 3a displays the volumetric flow rates of the blood suspension Qtotal and of the RBCs QRBC through the channel. When the pressure gradient is applied, the blood suspension begins to flow forward and both flow rates increase gradually. Unlike that for a pure fluid, the total flow rate Qtotal exhibits random fluctuations and only a quasi-steady stable state can be established, since the RBC configuration is constantly changing. Such fluctuations are more profound in the RBC flow rate QRBC , because any RBC configuration change will affect both the velocity and index distributions, see Eq. (8). The resulting discharge hematocrit value for this simulated case, HD = 38.9%, is higher than the tube hematocrit HT = 32.2%, and consistent with the well-known Fahraeus effect.

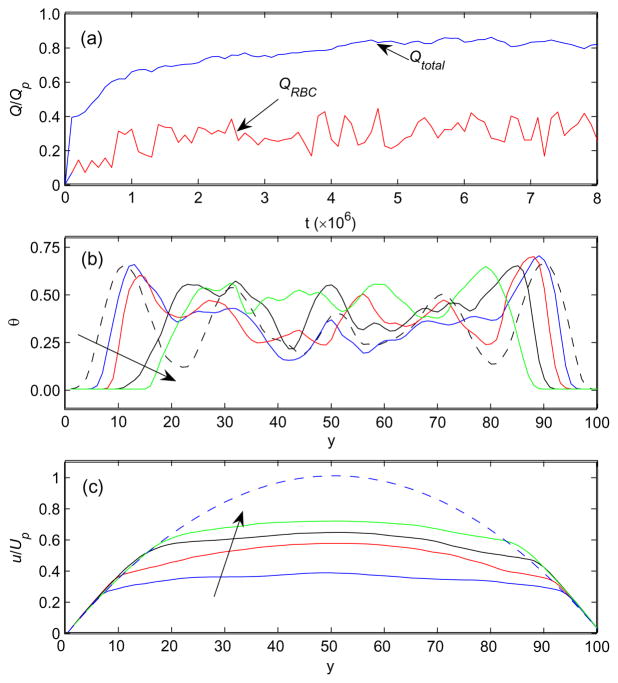

FIG. 3.

(a) The total and RBC flow rates, (b) the averaged θ distributions, and (c) the averaged velocity profiles during the developing process. In (b) and (c), the profiles are taken at t = 0.4, 1.0, 3.0, and 7.0 ×106 in the arrow directions. The dashed lines are the initial θ distribution in (b) and the parabolic velocity profile of a pure plasma flow under the same pressure gradient in (c). Qp and Up, respectively, are the flow rate and maximum velocity of such a plasma flow. The time t and position y are presented in time steps (Δt = 1.25 ×10−8 s) and lattice units (h = 0.195 μm), respectively. Other quantities are dimensionless.

Figure 3b shows the RBC distribution profiles during the flow development, where θ has been averaged along the channel. It can be seen that, as time progresses, a layer of θ = 0, which by definition is pure plasma, develops near each boundary surface and its thickness increases with time. Also displayed in Figure 3c are the streamwise averaged velocity profiles at several time points. As observed in in-vivo and in-vitro experiments [1], such velocity profiles have blunt shapes due to the high fluid viscosity of the RBC-rich core in the central region. Compared to a pure plasma flow under the same pressure gradient (Figure 3c, dashed line), the flow rate of blood suspension Qtotal is smaller, and the relative apparent viscosity μrel = 1.29 is larger than unit, indicating an increase in flow resistance due to the RBC presence.

Similar 2D systems have been investigated by Sun and Munn [11] and Bagchi [12]. Aggregation was not considered in those studies. For rigid RBCs with HT = 30.5% flowing in a 20 μm channel, Sun and Munn [11] found that the relative apparent viscosity μrel was 1.50 and hematocrit ratio HT /HD was 0.90. Such values are close to our results for less deformable RBCs with no aggregation, i.e., μrel = 1.66 and HT /HD = 0.875. The differences may be due to the different tube hematocrit and RBC shapes, as well as the slight deformability in our simulation. Also no clear CFLs were observed in Ref. [11] as in the top-right panel in our Figure 4. Recently, Bagchi [12] employed a similar RBC model and studied deformable RBCs with HT = 33% also in a 20 μm channel. The CFL thickness was about 2.8 μm, which is in a good agreement with the two-phase model by Sharan and Popel [5], and is close to our estimate of δ = 2.44 μm for the normal RBCs with no aggregation. However, the relative apparent viscosity μrel = 1.60 obtained by Bagchi is much larger than our result μrel = 1.27 The reason for this discrepancy is not clear One possibility is the different mean flow viscosities as discussed by Bagchi.

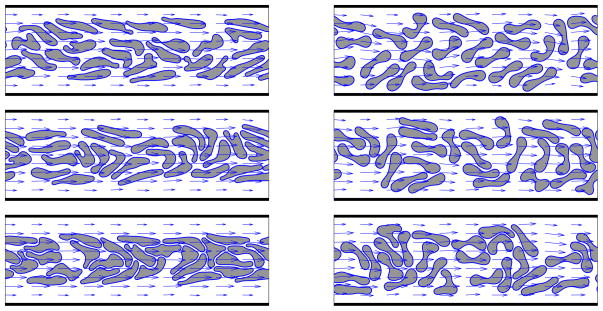

FIG. 4.

The relative stable states of the blood flows with different deformabilities (left: normal; right: less deformable) and aggregation strengths (from top to bottom: none, moderate, and strong). The flow fields are also displayed by arrows. The simulation domain is 19.5 × 58.5 μm.

Unlike these previous 2D numerical studies, we have not attempted to compare our simulation results to the empirical relationships proposed by Pries et al. [34]. We believe that 2D studies, although valuable, can only provide qualitative information. For example, the CFL/RBC-core cross-sectional area ratio are 2δ/H and 4δ (D − δ)/D2 (D is the vessel diameter) for 2D and 3D situations, respectively. For δ = 3 μm and H = D = 20 μm, 2δ/H = 0.3 and 4δ (D − δ)/D2 = 0.51, implying a less profound CFL lubrication effect and a lower core hematocrit in 2D simulations compared to the corresponding 3D systems. Also the apparent viscosity of a RBC suspension may be very different in 2D and 3D systems, even with the same hematocrit. It is interesting to note that Sun and Munn [11] found a good agreement to the Pries formula [34] for the hematocrit-viscosity relationship, although the cells were represented as rigid particles. However, for HT = 30.5% in a 20 μm channel, the simulated discharge hematocrit HD by Sun and Munn was 33.9%, while the prediction according to Pries et al. [34] is 42.5%. In Ref. [12] Bagchi reported a similar agreement of the HD ~ μrel relationship to the Pries empirical formula. However, the discharge hematocrit HD was not obtained from simulations, although it is readily available from the velocity and index distributions as shown in Eq. (9).

C. Effects of Cell Deformability and Aggregation

The simulations with different RBC deformabilities and aggregation strengths (Table I) are summarized in Figures 4 and 5 and Table II. Less deformable RBCs are modeled by increasing the membrane shear and bending modular to twenty times of their normal values, i.e., Es = 1.2 × 10−4 N/m and Eb = 4.0 × 10−18 Nm. Three different aggregation strengths, De = 0 (none), 5.2 × 10−8 (moderate), and 1.3 × 10−6 μJ/μm2 (strong), were employed based on previous numerical studies [20]. In Figure 4, we plot the quasi-steady states of the six situations with different deformabilities and aggregation strengths. Clearly, many less deformable RBCs (right column in Figure 4) preserve their original biconcave shape and the deformations of others are less evident, when compared with their counterparts with normal RBCs (left column in Figure 4). Another feature is the presence of CFLs near the channel boundaries: Except for the case with less deformable RBCs and no aggregation capability (Figure 4, top-right), obvious CFLs can be seen. The CFL thickness increases with both the aggregation and the cell deformability, since a stronger aggregability tends to attract RBCs closer and generate a more concentrated RBC core. For less deformable RBCs, the membrane rigidity prevents large deformation and large cell-cell contact area, resulting in a less dense RBC core and thinner CFLs than with normal RBCs. Similar behaviors have been reported in previous studies [11, 12]. Also displayed in Figure 4 are the blunt velocity distributions.

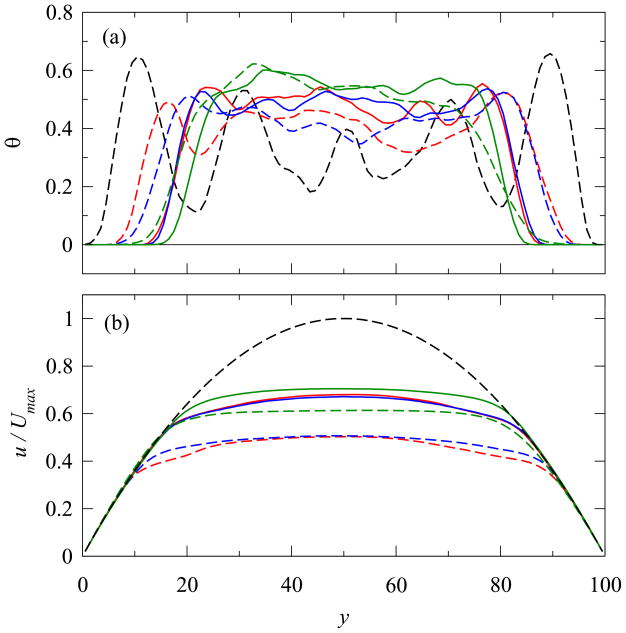

FIG. 5.

(a) θ distributions and (b) velocity profiles at the relative stable states with different deformabilities and aggregation strengths. The dashed lines are the initial θ distribution in (a) and the parabolic velocity profile of a pure plasma flow under the same pressure gradient in (b). Up is the maximum velocity of such a plasma flow. The line thickness indicates the cell deformability (thick: less deformable, and thin: normal), and the color is for the aggregation strength (black: none, blue: moderate, and red: strong). The position y is presented in lattice units (h = 0.195 μm), and other quantities are dimensionless.

TABLE II.

CFL thickness δ, relative apparent viscosity μrel, and discharge hematocrit HD for different cell deformabilities and aggregation strengths

| Deformability | Aggregation | δ (μm) | μrel | HD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| less deformable | None | 1.32 | 1.66 | 36.8 |

| moderate | 1.52 | 1.60 | 37.4 | |

| strong | 2.45 | 1.34 | 39.6 | |

| normal | none | 2.44 | 1.27 | 38.8 |

| moderate | 2.69 | 1.29 | 38.9 | |

| strong | 3.18 | 1.23 | 40.0 |

In Figure 5, we have plotted the averaged fluid index θ and streamwise velocity u for these six different cases. CFLs (θ = 0 regions in Figure 5a) have developed near the boundaries and concentrated RBC cores with high θ values have formed in the central region. The measured CFL thicknesses δ are listed in Table II. Clearly δ increases with both the cell deformability and aggregation strength. For the less deformable RBCs with no aggregation, no CFLs are evident in Figure 4b, similar to the findings of Sun and Munn [11], where RBCs were modeled as rigid particles. The measured δ for this case is 1.32 μm, the smallest value in all six cases. The relative apparent viscosities calculated according to Eq. (10) are listed in Table II. All these relative viscosities are greater than 1 because of the existence of RBCs. Obviously the RBC deformability plays a definitive role. The relative apparent viscosity increases with a decrease in cell deformability. However, the aggregation effect is more complex. With stronger aggregation, the denser RBC core has a higher viscosity; whereas the larger CFL will generate a more significant lubricating effect, which tends to reduce the global apparent viscosity. This finding may help to explain the contradictory experimental findings in the literature [35]. In our simulations at low flow rates, the lubrication effect appears more profound, and the relative apparent viscosity μrel generally decreases with aggregation. This trend is in a good agreement with experimental findings by several groups [36–39]. However, when moderate aggregation is introduced, μrel indeed increases slightly compared to the case with no aggregation, indicating that the larger core viscosity has suppressed the lubrication benefit from thicker CLFs. We have also calculated the discharge hematocrit HD by Eq. (9) and the tube-discharge hematocrit ratio HT /HD. The tube hematocrit HT is the same, 32.3%, for all cases, and the discharge hematocrit HD varies from 36.8% to 40.0%. The corresponding HT /HD ratios changes from 0.875 to 0.805, all less than 1, the well-known Fahraeus effect.

IV. SUMMARY

A recently developed IBM-LBM model has been applied to study the effects of RBC deformability and aggregation on the hemodynamic and hemorheological behaviors of microscopic blood flows. When a pressure gradient is applied, RBCs near the channel boundaries migrate toward the channel center, creating a concentrated RBC core, and plasma fluid in that region is displaced toward the CFL regions. Tank-treading motion of the RBCs also occurred. We found that a fluid particle is likely to be displaced laterally by RBCs, unless it is closely surrounded by RBCs. This finding may help to explain the typical U-shaped distribution of platelets in microvessels observed experimentally [33]. In addition, several typical microscopic hemodynamic and hemorheological characteristics have been observed, such as the blunt velocity profile, changes in apparent viscosity, and the Fahraeus effect. We also found that CFL thickness increases with cell deformability, since the membrane deformability allows the cells to deform and create a concentrated core. However, the influence of aggregation is more complex due to the opposing effects of the CFL lubrication and the high RBC core viscosity. This leads to a decrease in effective viscosity with higher levels of aggregability in our study, in agreement with in vitro experimental findings [38]. Overall, we find that our model predicts important aspects of blood flow behaviors observed both in microcirculatory vessels and in vitro. This suggests that the model may also be helpful in understanding the factors involved, for example, in the intravascular distribution and delivery to target organs of stem cells, drugs and genetic materials that are less amenable to experimental study. Extending this model to 3D systems would provide more quantitative results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants HL18292 and HL079087. J. Zhang acknowledges the financial support from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and a start-up grant from the Laurentian University. P. C. Johnson is also a Senior Scientist at La Jolla Bioengineering Institute. This work was made possible by the facilities of the Shared Hierarchical Academic Research Computing Network (SHARCNET:www.sharcnet.ca).

Appendix: The Immersed Boundary Lattice Boltzmann Method for Deformable Liquid Capsules

A. The Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM)

In LBM, a fluid is modeled as pseudo-particles moving over a lattice domain at discrete time steps. The major variable in LBM is the density distribution fi(x, t), indicating the particle amount moving in the i-th lattice direction at position x and time t. The time evolution of density distributions is governed by the so-called lattice Boltzmann equation, which is a discrete version of the Boltzmann equation in classical statistical physics [29, 40]:

| (A.1) |

where ci denotes the i-th lattice velocity, Δt is the time step, and Ωi is the collision operator incorporating the change in fi due to the particle collisions. The collision operator is typically simplified by the BGK [41] single-time-relaxation approximation:

| (A.2) |

where τ is a relaxation parameter and the equilibrium distribution can be expressed as i [42]

| (A.3) |

Here ρ = Σifi is the fluid density and u = Σifi ci/ρ is the fluid velocity. Other parameters, including the lattice sound speed cs and ti, are lattice structure dependent. Through the Chapman-Enskog expansion, one can recover the macroscopic continuity and momentum (Navier-Stokes) equations from the above-defined LBM microdynamics:

| (A.4) |

| (A.5) |

where ν is the kinematic shear viscosity given by

| (A.6) |

and P is the pressure expressed as

| (A.7) |

It can be seen from the above description that the microscopic LBM dynamics is local (i.e., only the very neighboring lattice nodes are involved to update the density distribution fi), and hence a LBM algorithm is advantageous for parallel computations [29]. Also its particulate nature allows it to be relatively easily applied to systems with complex boundaries, such as flows in porous materials [29]. Such features could be valuable for future studies of RBC flows in more complicated and realistic systems.

B. The Immersed Boundary Method

In the 1970s, Peskin [10] developed the novel immersed boundary method (IBM) to simulate flexible membranes in fluid flows. The membrane-fluid interaction is accomplished by distributing membrane forces as local fluid forces and updating membrane configuration according to local flow velocity.

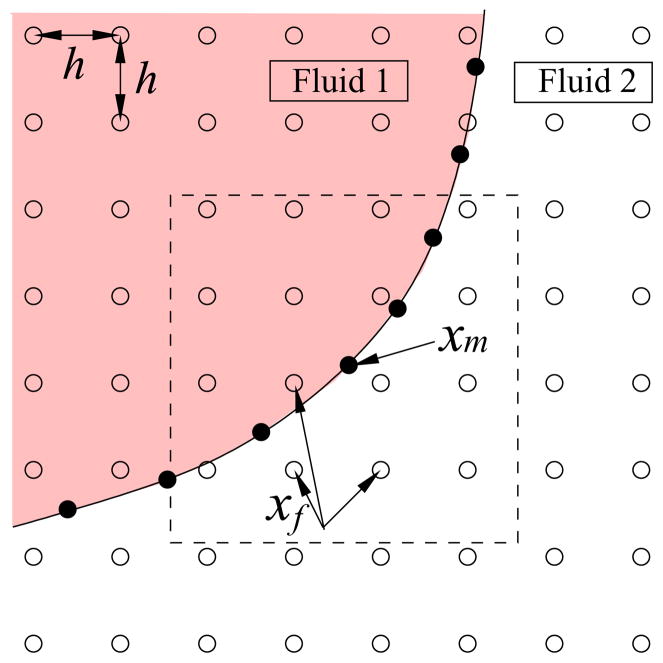

Figure A.1 displays a segment of membrane and the nearby fluid domain, where filled circles represent membrane nodes and open circles represent fluid nodes. In IBM, the membrane force f(xm) at a membrane marker xm induced by membrane deformation is distributed to the nearby fluid grid points xf through a local fluid force

FIG. A.1.

A schematic of the immersed boundary method. The open circles are fluid nodes and the filled circles represent the membrane nodes. The membrane force calculated at node xm is distributed to the fluid nodes xf in the 2h × 2h square (dashed lines) through Eq.(A.8); and the position xm is updated according to xf velocities through Eq.(A.11).

| (A.8) |

through a discrete delta function D(x), which is chosen to approximate the properties of the Dirac delta function [9, 10, 43]. In our two-dimensional system, D(x) is given as

| (A.9) |

| (A.10) |

Here h is the lattice unit. The membrane velocity u(xm) can be updated in a similar way according to the local flow field:

| (A.11) |

We note that both the force distribution Eq.(A.8) and velocity interpolation Eq.(A.11) should be carried out in a 4h × 4h region (dashed square in Figure A.1) [10], instead of a circular region of radius 2h as described elsewhere [43–45]. This is due to the specific approximation of the delta function Eq.(A.9) adopted in IBM. It can be shown that the sum of non-zero values of Eq.(A.9) in the square region is 1, and hence missing any nodes inside the square and outside of the circle of radius 2h would produce an inaccuracy in fluid forces and membrane velocity.

C. Fluid Property Update

The fluids separated by the membrane can have different properties, such as density and viscosity. In our system, the densities of cytoplasm of RBC and plasma are similar and the difference could be neglected for low Reynolds numbers. However, for normal RBCs, the viscosity of cytoplasm is 5 times of that of the suspending plasma. As the membrane moves with the fluid flow, the fluid properties (here the viscosity) should be adjusted accordingly. This process seems straightforward; however, it is not trivial. Typically, an index field is introduced to identify the relative position of a fluid node to the membrane. In previous IBM studies, Tryggvason et al. [46] solved the index field through a Poisson equation over the entire domain at each time step, but the available information from the explicitly tracked membrane is not fully employed [45]. On the other hand, Shyy and coworkers [43–45] suggested to update the fluid properties directly according to the normal distance to the membrane surface. We prefer the latter approach for its simple algorithm and computational efficiency. However, the originally proposed formulations of the Heaviside function are coordinate dependent [20]. To overcome this drawback, here we modify this approach by simply defining an index d of a fluid node as the shortest distance to the membrane. If the node is close to two or more membrane segments, the index taken is that to the closest one. This index also has a sign, which is negative outside of the membrane and positive inside. Similar to the approach of Shyy and coworkers [43, 44], a Heaviside function is defined as

| (A.12) |

A varying fluid property α can then be related to the index d by

| (A.13) |

where the subscripts in and out indicate, respectively, the bulk values inside and outside of the membrane. It can be seen from Eq.(A.12) that, as the membrane moves, only the nodes close to the membrane (|d| ≤ 2h) will be affected. Therefore, in the computer program we need only to calculate the index and update the fluid properties in the vicinity of the membrane. Such a process should be more efficient than solving a Poisson equation over the entire fluid domain [46].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Popel AS, Johnson PC. Microcirculation and hemorheology. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 2005;37:43–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.fluid.37.042604.133933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mchedlishvili G, Maeda N. Blood flow structure related to red cell flow: a determinant of blood fluidity in narrow microvessels. Japanese Journal of Physiology. 2001;51(1):19–30. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.51.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoltz JF, Singh M, Riha P. Hemorheology in Practice. IOS Press; Amsterbam, Netherlands: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumler H, Neu B, Donath E, Kiesewetter H. Basic phenomena of red blood cell rouleaux formation biorheology. Biorheology. 1999;36:439–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharan M, Popel AS. A two-phase model for blood flow in narrow tubes with increased viscosity near the wall. Biorheology. 2001;38:415–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pozrikidis C. Finite deformation of liquid capsules enclosed by elastic membranes in simple shear flow. Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 1995;297:123–152. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pozrikidis C. Effect of membrane bending stiffness on the deformation of capusles in simple shear flow. Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 2001;440:269–291. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pozrikidis C. Numerical simulation of the flow-induced deformation of red blood cells. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2003;31:1194–1205. doi: 10.1114/1.1617985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eggleton CD, Popel AS. Large deformation of red blood cell ghosts in a simple shear flow. Physics of Fluids. 1998;10(8):1834–1845. doi: 10.1063/1.869703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peskin CS. Numerical analysis of blood flow in the heart. Journal of Computational Physics. 1977;25(3):220–252. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun C, Munn LL. Particulate nature of blood determines macroscopic rheology: A 2-D lattice Boltzmann analysis. Biophysical Journal. 2005;88(3):1635–1645. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.051151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagchi P. Mesoscale simulation of blood flow in small vessels. Biophysical Journal. 2007;92(6):1858–1877. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.095042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bishop JJ, Popel AS, Intaglietta M, Johnson PC. Rheological effects of red blood cell aggregation in the venous network: a review of recent studies. Biorheology. 2001;38:263–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Zhang L, Wang X, Liu WK. Coupling of Navier-Stokes equations with protein molecular dynamics and its application to hemodynamics. International Journal of Numerical Methods in Fluids. 2004;46:1237–1252. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bagchi P, Johnson PC, Popel AS. Computational fluid dynamic simulation of aggregation of deformable cells in a shear flow. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2005;127:1070–1080. doi: 10.1115/1.2112907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung B, Johnson PC, Popel AS. Application of chimera grid to modeling cell motion and aggregation in a narrow tube. International Journal of Numerical Methods in Fluids. 2006;53(1):105–128. doi: 10.1002/fld.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neu B, Meiselman HJ. Depletion-mediated red blood cell aggregation in polymer solutions. Biophysical Journal. 2002;83:2482–2490. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75259-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun C, Munn LL. Influence of erythrocyte aggregation on leukocyte margination in postcapillary expansions: A lattice Boltzmann analysis. Physica A. 2006;362:191–196. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Johnson PC, Popel AS. An immersed boundary lattice Boltzmann approach to simulate deformable liquid capsules and its application to microscopic blood flows. Physical Biology. 2007;4:285–295. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/4/4/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, Johnson PC, Popel AS. Red blood cell aggregation and dissociation in shear flows simulated by lattice Boltzmann method. Journal of Biomechanics. 2008;41:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans EA, Fung YC. Improved measurements of the erythrocyte geometry. Microvascular Research. 1972;4:335–347. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(72)90069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hochmuth RM, Waugh RE. Erythrocyte membrane elasticity and viscosity. Annual Review of Psychology. 1987;49:209–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.49.030187.001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans EA. Bending elastic modulus of red blood cell membrane derived from buckling instability in micropipette aspiration tests. Biophysical Journal. 1983;43:27–30. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merill EW, Gilliland ER, Lee TS, Salzman EW. Blood rheology: Effect of fibrinogen deduced by addition. Circulation Research. 1966;18:437–446. doi: 10.1161/01.res.18.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brooks DE. Electrostatic effects in dextran mediated cellular interactions. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 1973;43:714–726. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chien S, Jan KM. Red cell aggregation by macromolecules: Roles of surface adsorption and electrostatic repulsion. Journal of Supramolecular Structure. 1973;1:385–409. doi: 10.1002/jss.400010418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baumler H, Donath E. Does dextran really significantly increase the surface potential of human red blood cells? Studia Biophysica. 1987;120:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans E, Needham D. Attraction between lipid bilayer membranes - comparison of mean field theory and measurements of adhesion energy. Macromolecules. 1988;21:1822–1831. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Succi S. The Lattice Boltzmann Equation. Oxford Univ. Press; Oxford: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Kwok DY. Pressure boundary condition of the lattice Boltzmann method for fully developed periodic flows. Physical Review E. 2006;73:047702. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.73.047702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmid-Schobein GW, Usami S, Skalak R, Chien S. Interaction of leukocytes and erythrocytes in capillary and postcapillary vessels. Microvascular Research. 1980;19:45–70. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(80)90083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S, Kong RL, Popel AS, Intaglietta M, Johnson PC. A computer-based method for determination of the cell-free layer width in microcirculation. Microcirculation. 2006;13:199–207. doi: 10.1080/10739680600556878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aarts P, van der Broek S, Prins G, Kuiken G, Sixma J, Heethaar R. Blood platelets are concentrated near the wall and red blood cells, in the center in flowing blood. Arteriosclerosis. 1988;6:819–824. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.8.6.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pries AR, Neuhaus D, Gaehtgens P. Blood viscosity in tube flow: dependence on diameter and hematocrit. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H1770–H1778. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.6.H1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baskurt O, Meiselman H. Hemodynamic effects of red blood cell aggregation. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 2007;45:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alonso C, Pries CA, Kiesslich O, Lerche D, Gaehtgens P. Transient rheological behavior of blood in low-shear tube flow - velocity profiles and effective viscosity. American Journal Of Physiology-Heart And Circulatory Physiology. 1995:268. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.1.H25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cokelet G, Goldsmith H. Decreased hydrodynamic resistance in the 2-phase flow of blood through small vertical tubes at low flow-rates. Circulation Research. 1991;68:1–17. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinke W, Gaehtgens P, Johnson PC. Blood viscosity in small tubes - effect of shear rate, aggregation, and sedimentation. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;253:H540–H547. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.3.H540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murata T. Effects of sedimentation of small red blood cell aggregates on blood flow in narrow horizontal tubes. Biorheology. 1987;33:267. doi: 10.1016/0006-355X(96)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Junfeng, Li Baoming, Kwok Daniel Y. Mean-field free-energy approach to the lattice Boltzmann method for liquid-vapor and solid-fluid interfaces. Physical Review E. 2004;69(3):032602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.69.032602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhatnagar P, Gross E, Krook K. A model for collisional processes in gases I: Small amplitude processes in charged and neutral one-component system. Physical Review B. 1954;94(3):511–525. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Junfeng, Kwok Daniel Y. A 2D lattice Boltzmann study on electrohydrodynamic drop deformation with the leaky dielectric theory. Journal of Computational Physics. 2005;206(1):150–161. [Google Scholar]

- 43.N’Dri NA, Shyy W, Tran-Son-Tay R. Computational modeling of cell adhesion and movement using a continuum-kinetics approach. Biophysical Journal. 2003;85(4):2273–2286. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74652-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Francois M, Uzgoren E, Jackson J, Shyy W. Multigrid computations with the immersed boundary technique for multiphase flows. International Journal of Numerical Methods for Heat and Fluid Flow. 2003;14(1):98–115. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Udaykumar HS, Kan H-C, Shyy W, Tran-Son-Tay R. Multiphase dynamics in arbitrary geometries on fixed Cartesian grids. Journal of Computational Physics. 1997;137(2):366–405. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tryggvason G, Bunner B, Esmaeeli A, Juric D, Al-Rawahi N, Tauber W, Han J, Nas S, Jan YJ. A front-tracking method for the computations of multiphase flow. Journal of Computational Physics. 2001;169(2):708–759. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skalak R, Chien S. Handbook of Bioengineering. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waugh RE, Hochmuth RM. Chapter 60: Mechanics and deformability of hematocytes. In: Bronzino JD, editor. Biomedical Engineering Fundamentals. 3. CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. pp. 60–3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.