Abstract

In 2001, the 77th Texas legislature passed Senate Bill 19 (SB19) requiring elementary school children in publicly funded schools to participate in physical activity (PA) and schools to implement a coordinated school health program (CSHP) by September 1, 2007. We report on awareness of and adherence to SB19 in a statewide sample of elementary schools and a subsample in two public health regions located along the Texas/Mexico border. Statewide, structured interviews with principals indicated high awareness of SB19's requirements, but lower awareness of the need for parental involvement. Only 43% of Texas schools had adopted their coordinated program at one year or less prior to implementation deadline. Principals reported an average of 179 minutes of PE per week, higher than the 135 minute mandate. Among subsample border schools, principal PA reports triangulated with teacher logs and student reports. Further, direct observation of PE indicated 50% of class time was spent in MVPA, meeting the recommended level of PA intensity defined by Healthy People 2010. Differences observed by public health regions included: greater PA minutes in Region 10 (231 minutes compared to 217 minutes in Region 11), higher adoption CSHP (92% compared to 75%), more school health advisory committees (SHAC) (58% vs. 38%) and school-level SHACs (83% compared to 25%), and a lower prevalence of obesity in fourth grade students (21% compared to 32%). Differences by region suggest SB19 is not being adhered to equally across the state, and some regions may require further support to increase implementation. Results underscore the importance of continued monitoring of enacted legislation, that school-based legislation for child health requires funding and refinement to produce the original intent of the law.

Keywords: Texas, child, adolescent, physical education and training, physical activity, schools, health education, public policy, health policy, obesity

Introduction

The prevalence of overweight among children in Texas is higher compared to U.S.-wide estimates, especially among economically disadvantaged populations (1-3). National prevalence estimates indicate 16% of Mexican American adolescents are obese and 34% are overweight based on the CDC BMI-for-age growth charts (3). Among 4th grade students in Texas, Latino (31.1% of boys and 26.4% of girls) and African American (21.6% of boys and 30.8% of girls) have a higher prevalence of obesity compared to their Caucasian counterparts (17.7% and 13.7%) (1). Because Texas has a growing and young age distribution of at-risk minority populations (4) and obesity has been found to track from childhood to adulthood over time (5), the prevalence of obesity among Texas children is worrisome.

In response to health consequences and projected health care costs (3) of childhood obesity, the 77th Texas legislature passed Senate Bill 19 (SB19) in 2001, which requires elementary school children to participate in 30 minutes of daily physical activity (PA) or a total of 135 minutes per week. SB19 also required the Texas Education Agency (TEA) to recommend coordinated school health programs (CSHP) and that schools adopt and receive implementation training in “approved” programs by 2007. The CSHP must address classroom curriculum, physical activity, child nutrition services, and parental involvement. Additional details on Senate Bill 19 are provided elsewhere (6).

In January, 2003, the 78th legislature made amendments to Texas Education Agency statutes (28.004 and 38.013) by enacting Senate Bill 1357, which strengthened the scope and authority of school health advisory councils (SHAC) to include strategies for: (a) integrating school health services; (b) counseling and guidance services; (c) a safe and healthy school environment; and (d) school employee wellness. This legislation also: (a) broadened the availability of CSHP for elementary schools; (b) required an assessment of compliance with vending machine and food service guidelines; and (c) held schools accountable for public inspection of school health programs.

Although SB19 was enacted to improve the health of Texas children, it also sought to help ameliorate unintended negative consequences of Texas academic testing standards. Enacted in 1999, the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS) (7) was mandated for administration during the 2002-2003 school year. When performance standards were being introduced, many school districts cut back or eliminated “enrichment” elements of their curriculum (those not considered “foundation” curriculum). Often this meant fewer physical and health education contact hours and reduced recess time. Pate et al (8) mentions similar consequences across the US of the No Child Left Behind Act (8).

The passage of SB19 in Texas was significant since it was one of the first statewide efforts to target child health through mandated PA time and health education. When SB19 was enacted and still today there was no additional funding for implementation or evaluation. In addition, accountability standards were not enacted for this legislation, thus requiring non-state funding for determination of effects on children's health.

The purpose of this study was to assess the extent of implementation of SB19 in Texas elementary schools. We evaluated the implementation of SB19 related to physical activity and CSHP for the state as a whole and compared the implementation of components of SB19 in two economically disadvantaged border regions within Texas over time. The specific aims of the study were to: (a) assess awareness of and adherence to SB19 in a representative sample of Texas elementary schools; and (b) monitor implementation and impact of SB19 in Texas/Mexico border schools on: (i) school and district PA policy, (ii) weekly minutes of scheduled physical activity; (iii) quality of child PA during physical education class as defined by minutes engaged in moderate to vigorous physical activity, (iv) selected self-reported dietary and PA measures, and (v) child obesity.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

We employed a mixed methods approach by making use of existing and newly collected data. Unfortunately, funding for this project began after implementation of SB19, not allowing the opportunity for baseline data collection prior to 2001. We made use of data collected under the present funding and data from a statewide representative survey (School Physical Activity and Nutrition, or “SPAN”), funded by the Texas Department of State Health Services and administered during the 2004-05 school year (1).

The first aim of the study concerned an assessment of knowledge and adherence to SB19. We contacted the 171 schools measured during the 2004-05 SPAN survey and conducted a telephone interview. The original sampling design of the SPAN survey was based on a probability-based sample of elementary schools representative of Texas and individual public health regions (1). Using a cross-sectional study design, 169 of the 171 schools (98% response rate) were interviewed during the 2005-06 school year.

Aim 2 of the study concerned monitoring implementation and impact of SB19 among schools on the Texas/Mexico border. We selected schools from Texas Public Health Regions (PHR) 10 and 11 that had participated in the 2004-2005 SPAN survey. These regions represent the Texas-Mexico border cities of El Paso, Laredo, and Brownsville and were chosen because they represent communities with high rates of obesity, diabetes, and poverty. Children in these regions are economically disadvantaged (>75%) and largely Hispanic (>90%). In Region 10, twelve schools were invited and agreed to participate (100% response rate). In Region 11, twenty schools were invited and 8 agreed to participate, a 40% response rate. Reasons for non participation were involvement with other health research projects and poor performance on state academic standards.

Methods for monitoring the implementation and impact of SB19 in our sample of Texas/Mexico border schools included: (a) structured interviews with principal or designated key informant at the school level; (b) direct observation of 3rd- 5th grade physical education (PE) classes; (c) a time use log to assess how 4th grade students spent their PA time; (d) SPAN assessment of PA and nutrition behaviors in 4th grade students; and (e) objectively measured height and weight of 4th grade students. In assessing changes in BMI, self-reported physical activity, and dietary behaviors, we used a serial cross-sectional design in which 4th grade students in selected schools were assessed in 2004 with another sample of 4th graders were assessed in the same selected schools 2006/2007. All study objectives and methods were approved by the University of Texas Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Measures

Telephone Key Informant Interviews of School Policy Environment

A structured telephone interview was developed by the study team to assess awareness and adherence to SB19 with school principals or school principal designee. The interview schedule included items created to assess mandate-specific aspects of the SB19 policy, as well as items modeled off previous CATCH research (9). The questionnaire consisted of 28 items that assessed: awareness of the various requirements of SB19 and SB1357; information channels for learning about SB19; weekly minutes of school-scheduled physical activity by grade level, school adoption of a TEA approved coordinated school health program, and implementation status of a coordinated school health program (see Table 1). The interview was reviewed by physical activity and nutrition experts and was found to have good face validity. Pre-testing with 4 school administrators resulted in minor modifications.

Table 1.

Texas Senate Bill 19 Core Constructs Examined and Corresponding Data Collection Methods by Texas Study Sample.

Implementation of Texas Senate Bill 19 to Increase Physical Activity in Elementary Schools Study.

| Statewide School Sample | Region 10 & 11 School Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Informant Telephone Surveya | Key Informant Telephone Survey | Direct Observation (SOFIT)b | Teacher Logc | Student Report (SPAN)d | |

| Construct | |||||

| Awareness of 30 min./day or 135 min/week Physical Activity Mandate | X | X | |||

| Awareness of Cooridinated School Health Mandate | X | X | |||

| Awareness of District School Health Advisory Committee | X | X | |||

| Presence & composition of Local School Health Advisory Committee | X | X | |||

| Information Channels for Learning about SB19 | X | X | |||

| Adherence to Physical Activity Minutes Mandate (PA weekly/daily minutes) | X | X | X | X | X |

| Quality of Physical Activity in PE Class | X | ||||

| Adoption of Coordinated School Health Program (CSHP) | X | X | |||

| Intention to Adopt CSHP | X | X | |||

| Training status on CSHP | X | X | |||

| Implementation of CSHP | X | X | |||

| BMI/weight classification (measure of impact) | X | ||||

| Dietary characteristics | X | ||||

Abbreviations: CSHP, Coordinated School Health Program.

Key informants were primarily principals or principal designee from a representative sample of public elementary schools in Texas.

PE class observations of third, fourth, and fifth grade students' activity levels and lesson contexts were conducted.

Fourth grade classroom teachers from Regions 10 and 11 along the Texas/Mexico border completed a five-day log of student physical activity.

Fourth grade students completed a self-administered survey (SPAN) on physical activity and dietary behaviors.

Additional Measures in Regions 10 and 11

Log of Students' Structured Physical Activity

As an additional measure of adherence with SB19's weekly physical activity minutes mandate, we collected teacher-reported minutes of physical activity time in schools. Fourth grade classroom teachers in Regions 10 and 11 were asked to complete a 5-day log on structured PA programmed for their students during the 2006-2007 school year. The log tracked the location of PA (classroom, recess, PE class) and the amount of time spent in each location. The log was adapted from previous CATCH PE surveys and was pretested with elementary school teachers to assess comprehension resulting in minor revisions.

Direct Observation of Physical Activity in PE Class

Direct Observation of Physical Activity in PE Class was conducted by trained observers at schools in Regions 10 (in Spring 2008) and 11 (in Spring 2007) using the System for Observing Fitness Instruction Time (SOFIT). SOFIT uses direct observation to obtain a simultaneous measure of students' PA levels and lesson contexts in PE classes. Three assessments per school were carried out, one at each grade level (3rd, 4th, and 5th). Observers randomly selected four children during the course of a PE class and observed and recorded their activity levels based on a momentary time sampling method. Development and validation of the SOFIT has been extensively described elsewhere (10-12). SOFIT has been found to have strong interrater reliability (11) as well as validity when compared with accelerometers (10) and heart rate monitors (12).

School Physical Activity and Nutrition (SPAN)

The SPAN self-administered questionnaire was designed to assess nutrition behaviors, attitudes and knowledge, and PA behaviors among 4th, 8th and 11th grade students (only 4th grade was used in the present study). For this study, the SPAN provided additional measures of the impact of SB19 on self-reported physical activity and nutrition behaviors. The SPAN measures and protocols were developed, pilot tested, and assessed for reproducibility (13,14) and validity (15) with 4th and 8th grade students. SPAN survey items for the fourth grade questionnaire were found to have a moderate to high level of reproducibility (kappa >.40 for 90% of items). Previous day recall dietary questions were found to have a moderate to high percentage agreement when compared to 24-hour dietary recall (26% to 90%).

Height and Weight

Height and Weight were objectively assessed using digital platform scales and portable stadiometers. For this paper, BMI ≥ 95th percentile was considered obese (16) using CDC BMI-for-age and sex growth charts. The SPAN survey and height and weight measures were administered by trained data collectors at schools in Regions 10 and 11 during the spring semester in 2007 according to standardized protocols (1).

Statistical Analysis

Awareness of and adherence to SB19 were assessed using data from the key informant survey, 5-day logs of PA, and the SOFIT assessments. Data were summarized as proportions within Regions 10 and 11 (and 10/11 combined). P-values from z-score tests were calculated for comparison between Regions 10 and 11 as well as Regions 10/11 combined compared to Texas statewide. Student-level data from the SPAN survey were used to compute region-specific prevalence of standard BMI categories and mean and standard deviation of selected PA and dietary behaviors. Estimates were obtained from random-effects regression models adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity and parent language as fixed effects, and school as a random effect. Separate estimates were obtained for 2004 and 2007, and the differences between these two years within each region were evaluated using t-statistics for differences in means and z-scores for difference in proportions. All computations were performed using Stata v9.0 software (17).

Results

Statewide Findings

Table 2 presents findings from the key informant interviews based on a random sample of Texas elementary schools and schools specific to Regions 10 and 11. Of the 169 informants who participated in the interview, 77% were principals, 12% were assistant principals, and 5% were nurses, 3% were PE instructors, and the remaining 3% represented faculty and counselors. Overall, we found a high level of overall awareness of CSHP requirement (96% ±2) and required PA per day or per week (97% ±3 acknowledged awareness). However, 12% of the sample was not aware of the need to implement health education, physical activity, or the child nutrition services component as part of CSHP, and over 40% were not aware of the need to include a parental involvement component for CSHP. Most key informants had learned about SB19 requirements from their school district (70%) or a district PA policy statement regarding the legislation (69%) (Table 2).

Table 2. 2005-06 Telephone Survey of Texas Elementary Schools.

| Texas (n=169) % (95% CI) |

Region 10/11 (n=20) % |

Region 10 (n=12) % |

Region 11 (n=8) % |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Are you aware that Senate Bill 19 requires: | p-value refers to Texas vs Regions 10/11 | p-value refers to Region 10 vs 11 | ||

| K-5 Physical Education and CSHPa? | 96 (94-99) | 95 | 92 | 100 |

| 30 min of structured physical activity per day or 135 min/week? | 97 (94-100) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Implementation of TEAb approved CSHP? | 88 (83-93) | 95 | 92 | 100 |

| Four interrelated components: | ||||

| Health Education | 88 (83-93) | 95 | 92 | 100 |

| Physical Education | 88 (83-93) | 95 | 92 | 100 |

| Food Service | 84 (78-90) | 95 | 92 | 100 |

| Parental involvement | 59 (52-67) | 80** | 75 | 88 |

| Establishment of a District SHAC? | 70 (63-77) | 90** | 83 | 100 |

| How did you become aware of SB19? | ||||

| School district | 68 (61-75) | 65 | 75 | 50 |

| Professional education | 5 (2-9) | 5 | 0 | 13 |

| Physical education planning | ||||

| Did your district issue a PE policy statement regarding the PE requirements? | 69 (62-76) | 60 | 58 | 63 |

| Are the PE requirements in the annual campus improvement plan? | 40 (33-48) | 40 | 42 | 38 |

| Are the CSHP requirements in the annual campus improvement plan? | 27 (20-33) | 35 | 42 | 25 |

| Physical education implementation | ||||

| Minutes PE per week (Average K-5) | 179 (173-186) | 225*** | 231 | 217 |

| SHAC/Committee | ||||

| Are you aware of Federal law on school meals and wellness policy? | 49 (41-56) | 75*** | 75 | 75 |

| Has your district formed a SHAC? | 50 (43-58) | 50 | 58 | 38 |

| Has your school formed a SHAC? | 33 (25-40) | 60*** | 83 | 25*** |

| What is the composition of your SHAC: | ||||

| PE teacher | 27 (20-34) | 45** | 67 | 13*** |

| Teacher other than PE teacher | 20 (14-26) | 40*** | 58 | 13*** |

| Food service staff worker | 18 (12-24) | 45*** | 67 | 13*** |

| Coach | 5 (2-9) | 25*** | 33 | 13 |

| Student | 1 (-1-2) | 5* | 0 | 13 |

| Parent | 13 (8-18) | 25* | 33 | 13 |

| Administration staff member | 19 (13-25) | 15 | 25 | 0** |

| Other person | 25 (18-31) | 55*** | 75 | 25*** |

| Program adoption, training and implementation | ||||

| Has your school adopted a TEA approved CSPH program? | 43 (35-50) | 85*** | 92 | 75 |

| If yes, did your school attend training? | 96 (91-101) | 94 | 91 | 100 |

| If yes, has your school implemented the program? | 89 (81-96) | 88 | 82 | 100 |

CSHP: Coordinated School Health Program

TEA: Texas Education Agency

= < .05;

= < .10;

= < .15

The average minutes of structured student PA per week at the state level was 179, exceeding the 135 minimum minutes required by the legislation. Roughly half of schools reported that their school district had not formed a SHAC as mandated in SB19, and that only 33% of schools had formed a school-level health advisory committee. Furthermore, 43% reported having adopted a TEA approved CSHP. At the time of the survey, conducted one year prior to the TEA implementation deadline and three years post TEA requirements letter, only 40% and 27% of schools had included the PA minutes and CSHP requirements, respectively, in their campus improvement plans (Table 2).

Regions 10 & 11 Findings

Response rates for Regions 10/11 were determined using the 2005 – 2006 TEA 4th grade enrollment data for counties in public health regions 10 and 11. Out of 1,423 fourth grade students enrolled in Region 10, 589 students participated in the 2007 survey (41% participation rate). In Region 11, out of 869 enrolled, 637 students participated in the study (73% participation rate).

Regions 10 and 11 combined differed from Texas as a whole. Most importantly, Regions 10/11 averaged 46 more minutes per week of PE (p=.001), nearly double the rate of CSHP adoption (p=.0004), and a trend for greater awareness of the parental involvement component (p=.07) (Table 1). Although we found few differences between regions regarding awareness of Senate Bill 19, notable differences were found with implementation. Region 10 reported a higher number of PA minutes, 231 minutes compared to 217 in Region 11 (p = .26) and a greater proportion of district SHACs (58% in Region 10 compared to 38% in Region 11, p = .39), and higher school SHACs (83% compared to 25%, p = .01). Region 10 had a higher adoption rate of CSHP (92% compared to 75%), had PA requirements (42% compared to 38%) and CSHP requirements (42% compared to 25%) in their annual campus improvement plans (Table 1).

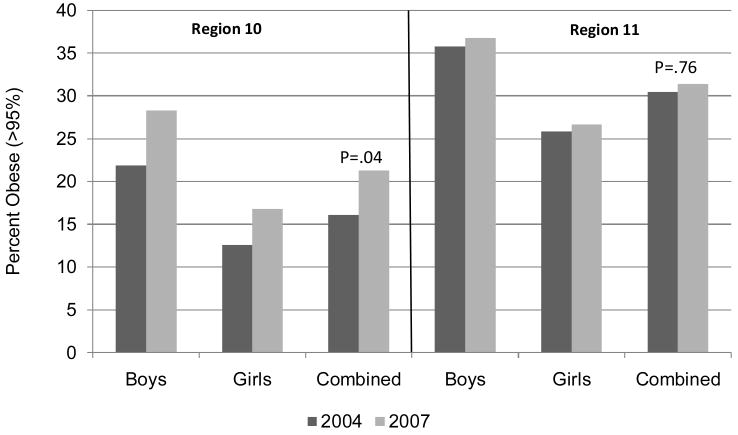

Table 3 presents 4th grade student BMI, prevalence of PA, and dietary behaviors for Regions 10 and 11 in 2004 and 2007. In schools from Region 10, we found prevalence of obesity to increase from 16.1% to 21.3% from 2004 to 2007 (p=.04). While no significant changes in BMI were observed for Region 11, it is important to note that the high prevalence of obesity (∼30%) was maintained.

Table 3. BMI and Self-reported Physical Activity and Dietary Behaviors of 4th Grade Children.

| Region 10 | Region 11 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 (n=348) | 2007 (n=609) | p value | 2004 (n=1,184) | 2007 (n=620) | p value | |

| BMI and BMI-for-age Percentilea,b | ||||||

| BMI | 19.18 (6.5) | 19.79 (5.5) | 0.02 | 21.3 (9.4) | 21.32 (7.3) | 0.96 |

| ≥95% (Obese) | 16.1 | 21.3 | 0.04 | 30.5 | 31.4 | 0.76 |

| ≥85th to<95th (Overweight) | 16.4 | 17.6 | 0.63 | 18.0 | 20.1 | 0.43 |

| Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviors (Mean, SD)b | ||||||

| Weekly PE classes | 4.21 (2.8) | 4.34 (2.6) | 0.17 | 3.12 (2.7) | 3.54 (2.1) | <.001 |

| TV/Video Viewing | 3.11 (6.9) | 2.61 (6.5) | 0.01 | 3.43 (5.1) | 2.94 (4.0) | 0.02 |

| Dietary Behaviors (Mean, SD)b | ||||||

| Number of times ate or drank | ||||||

| Milk | 1.52 (2.1) | 1.55 (1.9) | 0.61 | 1.22 (1.5) | 1.17 (1.2) | 0.34 |

| Healthy vegetablec | 1.03 (2.1) | 0.87(2.0) | 0.01 | 0.85(1.5) | 0.82(1.1) | 0.53 |

| Fruits | 1.28 (2.0) | 1.38 (1.8) | 0.12 | 1.17 (1.7) | 1.29 (1.3) | 0.09 |

| Fruit Juice | 0.94 (1.6) | 0.93 (1.4) | 0.92 | 0.92 (1.4) | 0.89 (1.1) | 0.58 |

| Soda | 0.62 (1.2) | 0.59 (1.0) | 0.62 | 0.73 (1.4) | 0.72 (1.1) | 0.86 |

| Sweet rolls | 0.57 (1.5) | 0.43 (1.4) | 0.00 | 0.44 (1.3) | 0.46 (1.0) | 0.68 |

| Candy | 0.39 (1.1) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.67 | 0.43 (1.3) | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.19 |

Based on CDC weight categorization: overweight: ≥85th to<95th%; obese: ≥95th%

Mean values adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, parent language use & school. Significant differences based on linear regression.

Composite variable of mean times ate orange vegetables (carrots), and other vegetables (tomatoes, cabbage, etc.). Scale 1-9 times.

While the mean number of days in PE class was greater in Region 10 in 2004 and 2007 compared to Region 11 (mean = 4.21 and 4.34 days, respectively), a significant increase was observed in Region 11 (from 3.12 to 3.54 days, p<.001). In both regions, we found a significant decrease in the mean hours of TV watching (p<.05). While few significant differences were found in dietary behaviors in the two regions between 2004 and 2007, we did observe a significant decrease in previous-day recall of consumption of sweet rolls, cakes, and other baked goods in 4th grade students from Region 10 (p<.001). Although both regions reported an increase in the mean times students consumed fruit between 2004 and 2007, these differences were not significant. Interestingly, we found a slight decrease in the mean consumption of vegetables for 4th grade students between 2004 and 2007 in Region 10 (from 1.03 to 0.87, p=.01) (Table 3).

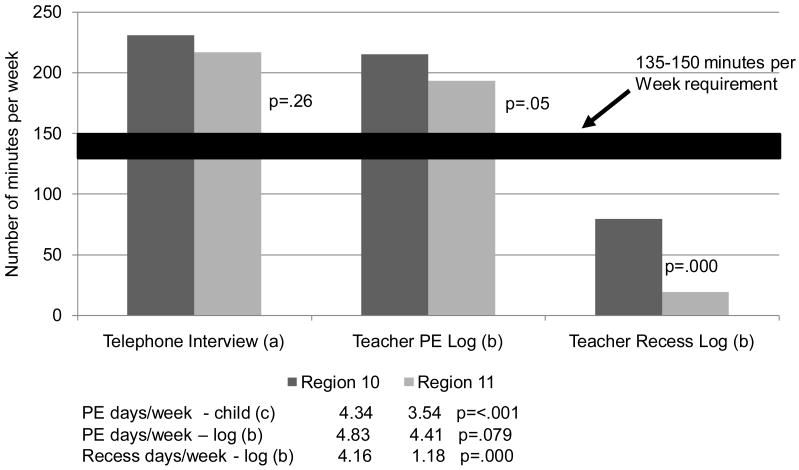

Figure 1 highlights the time that schools in Regions 10 and 11 provided opportunities for PA by summarizing data from three sources: (a) the key informant telephone interviews, (b) the 5-day logs of required PA, and (c) SPAN survey. Both regions exceeded the minimum required PA minutes per week (135), with schools in Region 11 offering between 14 (telephone survey, p=.26) and 22 (5-day teacher log, p=.05) fewer minutes per week. Further, the days that PE was offered to students was near or above four times per week, with schools in Region 11 offering .42 (p=.079) to .8 (p=.001) fewer days per week compared to schools in Region 10.

Figure 1. Reported Physical Education and Recess Minutes per Week.

- Telephone interview with school administrator/lead health teacher (n=18 schools)

- 5 day classroom teacher log of PE and recess (n= 18 schools; 63 teachers)

- Student survey (n=2,797 students)

Both the SPAN and SOFIT findings provide additional overlapping data on the trends observed in student PA minutes from in the key informant interview and teacher logs. Based on the SPAN questionnaire, 4th grade students in Regions 10 and 11 reported an average of 4.34 and 3.54 of PE days per week, respectively (Figure 1). Based on an average class time of 45 minutes per PE class, students would engage in 195 minutes and 159 minutes per week, respectively for Regions 10 and 11. When we add the recess estimated minutes from the Teacher logs (Figure 1), these estimates approximate those provided by key informants and teachers. For SOFIT results, we recorded an average of 44.1 minutes of scheduled PE class time per session and observed an average of 34.1 minutes of PE per session across regions (data not shown in tables). Given a five-day PE week (or 4 day PE week with the remainder representing recess), these findings provide further support for the 204-225 weekly minutes reported per region or 40.8-44.8 minutes of PA per day.

Figure 1 also provides data on the number of days and amount of time spent in recess. The 5-day log indicated a dramatic difference in recess, with 18.9 minutes per week in Region 11 and 79.4 minutes in Region 10 (p=.0001). Summing PE and recess time, students in Region 11 received between 74.5 to 82.5 fewer minutes of PA per week than Region 10.

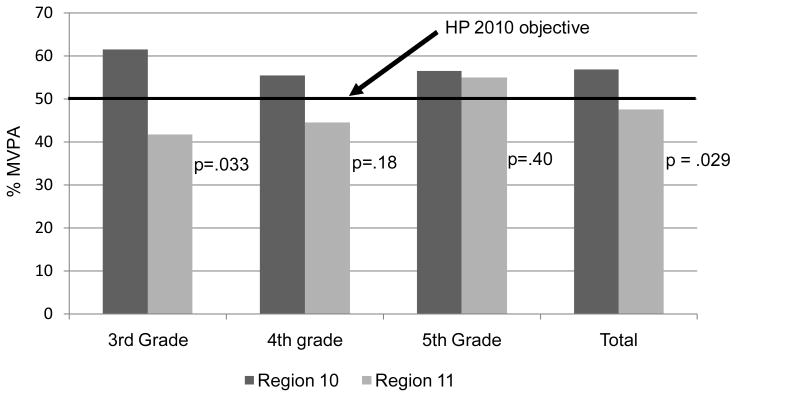

Figure 2 presents data on the quality of physical activity participation at the school level as per the SOFIT direct observations of PA in PE classes and the percentage of class time spent in moderate-to- vigorous physical activity (MVPA). At every grade level, students in Region 10 met the Healthy People 2010 benchmark of 50% of available PE class time devoted to MVPA. Students in Region 11 scored considerably lower in MVPA in 3rd grade students (p=.033) and overall (p=.029), 19.75% and 9.4%, respectively.

Figure 2. Direct Observation of PE Class (SOFIT; n = 19 schools).

MVPA = % of PE class time where students are engaged in movement to vigorous physical activity

Figure 3 illustrates data from Table 3 by gender. In both 2004 and 2007, the percentage of children who were obese were 10% to nearly 15% higher in Region 11 compared to Region 10 (2004 and 2007, both p<.05), and the obesity rate was 7-10% higher among boys in both regions. From 2004 to 2007, a 5% significant increase was observed in Region 10, and although nonsignificant, the rate of change was larger in boys and approached significance (p=.10).

Figure 3. Percent Obese * (>95%) by Region, 2004 and 2007.

*Adjusted for mean age, gender, ethnicity, language use and school

Discussion

Statewide, our results indicated a high level of awareness, action and compliance with the physical activity-related requirements of SB19. Based on self-reported data from school administrators and staff, on average elementary schools in Texas offered 179 (±6) minutes of PE per week, which is substantially higher than the minimum standard of 135 minutes. This finding was confirmed in Regions 10 and 11 by a 5-day log (204 minutes per week), SPAN survey with a mean of 3.94 days of PE per week, and SOFIT direct observation of 170.5 minutes of PE per week.

In addition, our findings also suggest that students in Regions 10 and 11 engaged in a sufficient level of PA during PE. While previous research on 3rd grade students in 10 sites around the United States found students spent an average of 37% time in MVPA during PE class (18), we found PA levels in 3rd, 4th, and 5th grade students near or above the Healthy People 2010 recommendation of 50% of available class time spent in MVPA.

The same was not observed with the mandate for coordinated school health programming. Most schools were aware of the need to implement a CSHP, yet 41% were unaware of the need for parental involvement. Recognizing that our study was conducted one year prior to the CSHP deadline, a 43% CSHP adoption rate suggests an important need being addressed by SB19. On a positive note, among CSHP adopting schools, 96% attended training and 89% reported implementation. We previously noted that school health programs with multiple components are challenging to implement without new school resources and support, including a program champion (19-21). The current academic structure of Texas schools is directed to increasing academic test scores, and health is not an accountable outcome. However, recent Texas legislation (SB530, 2007) has mandated fitness testing and public reporting for all students in grades 3-12. Time will tell if compliance to CSHP improves.

Our second study aim assessed the impact of SB19 in two economically disadvantaged areas along the Texas-Mexico border. Despite the lack of a baseline assessment, existing data provided a reference point to observe changes in health-related outcomes over time. Our first important finding was that students who attended border schools experienced a high obesity prevalence: 21.3% and 31.4% in Regions 10 and 11, respectively. This underscores the need for enhanced intervention efforts to reduce and prevent childhood obesity in these areas - efforts that should complement the current SB19 legislation. Secondly, although high in both regions, schools in Region 10 reported lower obesity rates compared to Region 11. We noted a greater adoption and implementation a TEA approved CSHP (the CATCH program) in Region 10, greater SHAC and school-level health committees, higher MVPA during PE and more recess time.

Although we cautiously interpret the regional differences, the reduced obesity rate in Region 10 suggests both the potential value of SB19 to support school based efforts as well as greater investments in community-based PA and nutrition programs. From the late 1990s thru 2005, the Paso del Norte Health Foundation supported implementation of several initiatives, including CATCH El Paso school health program (22), Qué Sabrosa Vida nutrition program (23), and the Walk El Paso project (24). Region 11, in contrast implemented the CATCH program, but did not implement a supporting large-scale community health program. It's worth noting we found increased obesity prevalence in Region 10 in 2007, two years after cessation of funding for CATCH El Paso. We speculate that multi-component, sustained and funded school and community interventions are needed in addition to legislation in order to curb the obesity epidemic.

Study limitations

As with all studies, ours has limitations. First, both the key informant survey and the SPAN questionnaire were self-reported, which may result in recall and social desirability bias. While we cannot rule out the possibility that key informants over-reported adherence to Senate Bill 19, we attempted to reduce self-report bias through the use of a limited number of trained interviewers who followed a standardized protocol and through examination of information from multiple data sources (key informant data, teacher logs, observed PE time, and student self-reported PE days). We found similar estimates and similar trends for each data source. Student estimates of participation in PE days provided the lowest estimates of PE minutes (ranging from 159 minutes to 195 minutes based on 3.54 to 4.34 days of PE per week and a session length of 45 minutes), but these estimates were still well above the 135 minutes of structured PA required by SB 19, providing further confidence in the validity of the data. A second limitation is relying on a state representative sample at a single point in time to determine awareness and implementation of SB19 requirements. Obviously multiple assessments would strengthen our confidence in the findings, yet our data did provided an in-depth view of the execution of this unfunded mandate. Finally, while we did attempt to assess change over time in the subsample of border schools, we did not have access to a non-intervention comparison state. As such, our single-group, pretest/posttest study design leaves unanswered several potential threats to internal validity, including: history, maturation, and statistical regression (25).

Implications for School Health Practitioners

Data from the 2006 School Health Policies and Programs Study (SHPPS) indicated that a comprehensive physical education program can provide opportunities for students to learn lifelong PA habits (26). However, to promote healthful behaviors and ultimately prevent chronic disease a CSHP should be adopted, implemented and sustained. Since the 1980's, research has shown that the broad framework of CSHPs facilitates the delivery of consistent health messages and garners collective efforts and resources to achieve school wellness goals (27). Numerous professional organizations recommend daily physical education from kindergarten through grade 12 (28) to combat childhood obesity. This recommendation could have greater impact on the health, welfare, and education of children as part of a CSHP.

Conclusions

Child nutrition and PA experts have only recently focused their efforts on policy as a tool to prevent childhood obesity. Data from this study suggest the importance of monitoring implementation progress of the requirements of state statues and making adjustments to ensure schools are in compliance, either by adding new provisions to the statute or by increasing accountability. Findings of this study suggest that health-related policies such as Senate Bill 19 can be communicated effectively to schools in a relatively short time period. At the same time, our mixed findings with regard to implementation of the legislation underscore the importance of not abandoning the legislation once it is passed. Lessons learned from this project indicate that school-based legislation for child health needs support from local community organizations, continued follow-up, evaluation and refinement to produce the effects that were the original intent of the law.

Acknowledgments

This project was primarily funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (#52467) to Steven H Kelder. It was also supported by grants from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIH CMHD P20MD000170-019001) and the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation.

Contributor Information

Steven H. Kelder, Professor at the University of Texas School of Public Health, Austin Regional Campus (UTSPH, ARC) and Co-Director of the Michael & Susan Dell Center for Advancement of Healthy Living (MSDCAHL). Steven.H.Kelder@uth.tmc.edu.

Andrew S. Springer, Assistant Professor at the UTSPH, ARC and Investigator at the MSDCAHL. Andrew.E.Springer@uth.tmc.edu.

Cristina S. Barroso, Assistant Professor at the UTSPH, Brownsville Regional Campus and Investigator at the MSDCAHL. Cristina.H.Barroso@uth.tmc.edu.

Carolyn L. Smith, Research Associate at the UTSPH, ARC and a member of the MSDCAHL. Carolyn.L.Smith@uth.tmc.edu

Eduardo Sanchez, Vice President and Chief Medical Officer at Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas. Eduardo_Sanchez@bcbstx.com

Nalini Ranjit, Faculty Associate at the UTSPH, ARC and Investigator at the MSDCAHL. Nalilni.Ranjit@uth.tmc.edu.

Deanna M. Hoelscher, Professor at the UTSPH, ARC and Director of the MSDCAHL. Deanna.M.Hoelscher@uth.tmc.edu.

References

- 1.Hoelscher DM, Day RS, Lee ES, et al. Measuring the prevalence of overweight in Texas schoolchildren. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(6):1002–1008. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1002. PMID: 15249306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freedman DS, Khan LK, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Secular Trends for Childhood BMI, Weight, and Height. Obesity. 2006:14, 301–308. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Texas Department of Health. Burden of Overweight and Obesity in Texas, 2000-2040. [September 1, 2008]; at : http://www.publichealthgrandrounds.unc.edu/catch/handout_txCost_Obesity_Report.pdf.

- 4.State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. [5-24-2008]; Available from: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/48000.html.

- 5.Kelder SH, Osganian S, et al. Tracking of Physical and Physiological Risk Variables among Ethnic Subgroups from Third to Eighth Grade: The CATCH Cohort Study. Prev Med. 2002 Mar;34(3):324–33. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Texas Education Agency. Senate Bill 19. [9/26/08]; http://www.tea.state.tx.us/curriculum/hpe/sb19faq.html.

- 7. [9/26/08]; For further information, see Texas Law http://www.tea.state.tx.us/rules/tac/chapter101/ch101b.html.

- 8.Pate RR, Davis MG, et al. Promoting physical activity in children and youth: a leadership role for schools. Circulation. 2006;114:1214–1224. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177052. PMID: 16908770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoelscher DM, Feldman HA, et al. School-based health education programs can be maintained over time: results from the CATCH Institutionalization study. Preventive Medicine. 2004;38:594–606. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKenzie TL, Sallis JF, Armstrong CA. Association between direct observation and accelerometer measures of children's physical activity during physical education and recess. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 1994;26:S143. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKenzie TL, Strikmiller PK, et al. CATCH: Physical activity process evaluation in a multicenter trial. Health Educ Q. 1994;(Suppl 2):S72–89. doi: 10.1177/10901981940210s106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKenzie TL, Sallis JF, Nader PR. SOFIT: system for observing fitness instruction time. J Teach Phys Educ. 1991;11:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penkilo M, George G, Hoelscher D. Reproducibility of the School-based Nutrition Monitoring Questionnaire among Fourth-grade Students in Texas. J Nut Ed and Beh. 2008;40(1):20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.04.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoelscher DM, McPherson RS, et al. Reproducibility and validity of the secondary level School-Based Nutrition Monitoring (SBNM) student questionnaire. J Amer Dietetic Assoc. 2003;103(2):186–194. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiagarajah K, Fly AD, et al. Validating the food behavior questions from the elementary school SPAN questionnaire. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008;40(5):305–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barlow SE and the Expert Committee. Expert Committee Recommendations Regarding the Prevention, Assessment, and Treatment of Child and Adolescent Overweight and Obesity: Summary Report. Pediatrics. 2007;120 Dec:S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software (Version 9) College Station, TX: StataCorp, LP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nader PR. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2. Vol. 157. 2003. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development Network. Frequency and intensity of activity of third-grade children in physical education; pp. 185–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoelscher DM, Feldman HA, et al. School-based health education programs can be maintained over time: results from the catch institutionalization study. Preventive Medicine. 2004;38(5):594–606. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franks A, Kelder SH, et al. School-based programs: lessons learned from CATCH, Planet Health, and Not-On Tobacco. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007 [serial online] Apr [cited2008 May 28]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2007/apr/06_0105.htm PMID: 17362624. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Owens N, Glanz K, Sallis J, Kelder SH. Evidence-based approaches to dissemination and diffusion of physical activity interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006 Oct;31(4 Suppl):S35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coleman KJ, Tiller CL, et al. Prevention of the Epidemic Increase in Child Risk of Overweigh tin Low-Income Schools: The El Paso Coordinated Approach to Child Health. ArchPediatrAdolescMed. 2005;159:217–22. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paso del Norte Foundation. Qué Sabrosa Vida. 2008a Retrieved on June 13, 2008 from: http://www.pdnhf.org/initiativedetail.asp?sec=goals&fr=s&id=67.

- 24.Paso del Norte Foundation. Walk El Paso. 2008b Retrieved on June 13, 2008 from: http://www.pdnhf.org/initiativedetail.asp?sec=goals&fr=s&id=70.

- 25.Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experimentation: design and analysis issues for field settings. Houghton Mifflin Company; Boston: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SM, Burgeson CR, et al. Physical education and physical activity: results from the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006. J Sch Health. 2007;77:435–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00229.x. PMID: 17908102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolbe LJ. A framework for school health programs in the 21st century. J Sch Health. 2005;75:226–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00028.x. PMID: 16014129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Association for Sport and Physical Education. Moving into the future: national standards for physical education. 2nd. Reston, VA: 2004. [Google Scholar]