Abstract

Negative emotional arousal in response to stress and drug cues is known to play a role in the development and continuation of substance use disorders. However, studies have not examined behavioral indicators of such arousal.

Objective

The current study examined behavioral and bodily arousal in response to stress and drug cue in individuals with alcohol dependence and cocaine dependence as compared to healthy controls using a new scale.

Methods

Fifty-two alcohol dependent (AD group), 45 cocaine dependent (COC group), and 68 healthy controls (HC group) were exposed to individually developed stressful, drug-cue, and neutral-relaxing imagery. Behavioral and bodily responses were assessed with a new scale, the Behavioral Arousal Scale (BAS).

Results

The BAS showed acceptable inter-rater reliability and internal consistency and correlated with subjective negative emotion and craving. BAS scores were higher in stress than neutral conditions for all three groups. COC participants showed higher BAS response to stress than AD or HC participants. COC and AD participants showed greater BAS response to drug cue than HC participants.

Conclusion

Behavioral arousal is a domain in which stress and drug related arousal is expressed and assessment of this domain could provide unique information about vulnerability to craving and relapse in addicted populations.

Keywords: behavioral, craving, stress, addiction

INTRODUCTION

Responses to stress and drug cues are known to be related to substance use disorders (Baker et al., 2004; Koob and Kreek, 2007; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2007; Sinha, 2001a; Sinha et al., 2006; Sussman et al., 1997; Wills and Hirky, 1996). Drug dependent individuals show altered responses to stress and drug cues, including greater emotional arousal and drug craving and dysregulated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and cardiovascular responses (Adinoff et al., 2005; Back et al., 2005; Contoreggi et al., 2003; Fox et al., 2008; Sinha et al., 2009), potentially due to neurobiological changes associated with protracted withdrawal states.

Drug dependent individuals may also show altered behavioral or bodily responses to stress and drug cues. However there has not been an investigation of these types of responses. Given that emotional, autonomic and HPA axis changes in stress and cue conditions are associated with relapse (Adinoff et al., 2005; Breese et al., 2005; Sinha et al., 2006), and that monitoring bodily cues for arousal and craving is an important aspect of relapse prevention in substance abuse treatment (O'Brien et al., 1998; Sinha, 2007), it is important to examine the behavioral arousal and bodily sensations in response to stress and drug cues in substance abusers.

Studies have examined behavioral and bodily distress associated with withdrawal in addicted populations using scales such as the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA; Sullivan et al., 1989) and the Clinical Institute Narcotics Assessment Scale (CINA; Peachey and Lei, 1988). However, this research focuses on acute withdrawal-related symptoms and may not be as useful in measuring stress-related behavioral and bodily arousal in healthy populations or in addicted individuals who are not in acute withdrawal.

The present study examined behavioral and bodily arousal in response to personalized stress and drug cue imagery in recently-abstinent alcohol dependent and cocaine dependent individuals, and healthy individuals. The assessment of behavioral and bodily arousal was based on theories of emotion (Ekman and Davidson, 1994; Lang, 1979; Lewis et al., 2008; vanGoozen et al., 1994) that propose that the experience of emotions and stress encompass behavioral and bodily sensations. Specifically, our measure of behavioral and bodily arousal assessed restlessness, muscle tension or aches, breathing changes, crying, sweating, stomach changes, and other sensations. We hypothesized that: (i) the cocaine dependent, alcohol dependent, and healthy control groups would all show increases in behavioral and bodily arousal following stress as compared to a neutral control condition, (ii) the cocaine and alcohol dependent groups would show greater increases in behavioral arousal in response to stress and drug cues than the healthy group, and (iii) behavioral and bodily arousal would be associated with increases in subjective negative emotion and drug craving following stress and drug cues.

METHODS

Participants

Ninety-seven individuals between the ages of 21 and 50 were recruited via advertisements placed in local newspapers. Fifty-two participants (42 men, 10 women) met criteria for current primary alcohol dependence (the AD group) and 45 participants (23 men, 22 women) met criteria for current primary cocaine dependence (the COC group). The cocaine dependent participants were all crack-cocaine users. These participants were admitted to a clinical research unit for 3–6 weeks of inpatient treatment and research participation. Sixty-eight healthy adults (34 men, 34 women) between the ages of 21 and 50 were also recruited from the community via local advertisements. The healthy control (HC) group were social drinkers; they reported drinking 25 drinks or less per month on the Quantity Frequency Variability Index (Cahalan et al., 1969). Structured clinical interviews (SCID I; First et al., 1995) and self-reports were conducted to assess current substance use disorders and breathalyzer and urine samples were obtained as an objective assessment of illicit drug use and current drinking levels. Healthy control participants were excluded if they met current or lifetime substance abuse or dependence criteria. All participants (AD, COC, and HC) were excluded if they met current criteria for any DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorder or if they were taking any medications for a psychiatric or medical problem. The study procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (as revised in 1983) and the study was approved by the University IRB. All participants gave their informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Procedures

Prior to the laboratory session, alcohol and cocaine dependent participants were admitted to a locked inpatient treatment research facility with no access to alcohol or drugs. While on the unit, subjects participated in a specialized 12-Step relapse prevention substance abuse treatment for 3–4 weeks (treatment was prior to the laboratory session). Urine and breathalyzer testing were conducted regularly to ensure abstinence. During the middle to end of their second week on the unit, the alcohol and cocaine dependent participants completed demographic and diagnostic assessments and completed an imagery script development session. Approximately 1 month after admission (M=30.61 days, SD=9.30 days), the laboratory sessions were conducted. Thus, participants were abstinent from substances and were not in acute withdrawal during the laboratory sessions. Ninety seven per cent of participants who were admitted to the unit remained through the laboratory sessions.

Healthy controls (HC) completed demographic, diagnostic, and script-development sessions in two to three assessment appointments. Urine testing was conducted at each appointment and subjects were excluded if they tested positive for substances at any assessment appointment. Subjects were also asked to abstain from alcohol use for 3 days prior to the laboratory sessions (which was confirmed by BAC analysis at the start of the laboratory sessions). HC participants were then admitted for a 3-day hospital stay on a clinical research unit for the laboratory session. During this 3-day period, they were required to stay on the unit, within a similar controlled environment as that of the alcohol and cocaine dependent participants.

In the laboratory sessions, all participants were seated in a comfortable position and then listened to one of three stories over headphones. The stories (also called “scripts”) were based on their real-life experiences of stressful situations, alcohol or cocaine-related situations, or neutral situations (for details on script content, see Imagery Script Development, below). The three stories were presented across three separate consecutive testing days with only one story presented per day. The story order was assigned randomly and counterbalanced across participants. Research staff conducting the laboratory sessions was unaware of the type of story (stress, alcohol or cocaine cue, neutral) and the content of the story that was played in the laboratory session. Participants also remained blind until the story was played.

Imagery script development

In a session prior to the laboratory sessions, scripts (stories) for the laboratory sessions were developed. The stress imagery script was based on the participant's description of a recent personal stressful event that was experienced as “most stressful”. Only situations rated as 8 or above on a 1–10 scale, with 10 being the most stressful recent event, were used for script development. Examples of stressful situations include a breakup or verbal argument with a significant other or being laid off from work. Trauma-related situations were not used for script development, as reliving traumatic events may be related to unique stress responses.

The alcohol or cocaine-cue script was based on the participant's description of a recent situation in which they desired alcohol or cocaine and then used alcohol or cocaine. Alcohol cue scripts were developed for alcohol dependent and healthy control participants (all of whom were social drinkers). Examples of alcohol-cue situations are buying alcohol or being at a bar. Cocaine cue scripts were developed for cocaine dependent participants. Cocaine cue scripts could not be developed for healthy control participants, as they did not have experience of regularly using cocaine. Examples of cocaine-cue situations are being offered cocaine by a drug using buddy or getting paid. For participants who met criteria for both alcohol and cocaine dependence, scripts were developed based on their primary substance use diagnosis. For alcohol and cocaine cue scripts, situations that occurred in the context of stress were not allowed.

Finally, a neutral/relaxing script was developed as a control for the stress and drug-related scripts. The neutral script was developed from the participant's individual experience of common relaxing situations, such as a summer day relaxing at the beach, taking a hot shower or bubble bath, and a fall day reading at the park.

For each script, specific details of the situation were elicited by having the participant complete the Scene Construction Questionnaire (Miller et al., 1987; Sinha et al., 1992), which obtains specific stimulus and response details, including specific physical and interpersonal context details, verbal and cognitive attributions regarding the people involved, and physiological and bodily sensations experienced for the situation being described. A 5-min “script” was then written in a standardized style and format for the stress, cue, and neutral situations for each participant and these were recorded on an audiotape in randomized order for presentation in the laboratory sessions. Script development procedures were based on methods developed by Lang and his colleagues (Lang et al., 1980; Miller et al., 1987), and further adapted in our previous studies (e.g., Fox et al., 2008; Sinha et al., 2003, 2009; Sinha and Parsons, 1996).

Habituation session

On a day prior to the laboratory sessions, participants were brought into the testing room in order to acclimate them to study procedures (e.g. rating forms) and to train them in imagery and relaxation, as described in our previous work (Sinha, 2001b; Sinha et al., 2003).

Laboratory sessions

On each laboratory day, participants were brought into the testing room by 8:00 AM, after a smoke break at 7:30 AM to address nicotine craving. This was followed by a 1-h adaptation period during which the participants were instructed to practice relaxation. At 9:10 AM, participants were provided headphones and listened to the script for 5 min. After imagery, participants were asked to stop imaging and relax as they remained in the testing room for 75 min to examine recovery from exposure to stress, alcohol or cocaine cue, and neutral imagery.

Measures

Behavioral and bodily response

The research assistant conducting the laboratory session rated participants' observed behavioral arousal and self-reported bodily arousal in person during the session, using the Behavioral Arousal Scale (BAS; Sinha, 2004; for scale items, see Table 1). The research assistant was trained in the use of this scale. This research assistant was a different person from the assistant conducting the script development sessions and was therefore unaware of which imagery script (stress, cue, or neutral) was being played on the tape on each day. The assistant rated the following behaviors based on their observations and, in some cases, their questioning of participants: restlessness, muscle tension, muscle ache, headache, quickened breathing, talking or facial movements, crying, sweating, and stomach changes. For the observable behaviors (e.g. crying), the item was scored based on the rater's observations of the participant. For the bodily sensations that are not observable (e.g. stomach changes), the rater asked the participant the question listed on the item. For items that could be observed and self-reported (e.g. restlessness), the rater observed the behavior and also asked the participant the question listed on the item. If the rater's observation diverged from the participant's rating, the higher score was recorded. Rating items via a combination of observation and questioning is a procedure that has been used in scales of withdrawal-related symptoms such as the CIWA (Sullivan et al., 1989) and the CINA (Peachey and Lei, 1988).

Table 1.

BAS items and inter-rater reliability

| Item | ICC | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Restlessness (Observation/question “Do you feel restless/fidgety?”) | 0.58 | |

| 0 | Normal Activity Level | |

| 1 | Patient reports being restless at end of the observation period | |

| 2 | Occasionally bounces foot/legs or moves limbs or shifts position | |

| 3 | Frequently moves limbs or shifts position | |

| 4 | Nearly constant movement or patient unable to remain in bed | |

| 2. Muscle tension (Observation/question “Do your muscles feel tight?”) | 0.58 | |

| 0 | No evidence of muscle tension | |

| 1 | Patient reports muscle tension when questioned | |

| 2 | Stretches or rubs muscles once or patient spontaneously complains of muscle tension once | |

| 3 | Stretches or rubs muscles more than once or more than 1 spontaneous complaint of muscle tension, aches or cramps | |

| 4 | Stretches or rubs muscles more than 3 times | |

| 3. Muscle aches (question “Do you have muscle aches?”) | NA | |

| 0 | None | |

| 1 | Mild | |

| 2 | Severe | |

| 4. Headache (question “Does your head feel different?”) | 0.95 | |

| 0 | None | |

| 1 | Mild | |

| 2 | Moderate | |

| 3 | Severe | |

| 5. Breathing (observation) | 0.95 | |

| 5a. | Rapid/fast breathing | |

| 5b. | Heavy/deep breathing | |

| 5c. | Slower breathing | |

| 5d. | Heavy sighs | |

| 6. Talking/expression (observation) | 0.89 | |

| 6a. | Patient begins to discuss imagery session | |

| 6b. | Patient begins smiling/laughing | |

| 6c. | Patient begins humming/singing** | |

| 6d. | Increased lower facial movements (e.g. lip licking/smacking) | |

| 7. Lacrimination/tearing (observation) | 1.00 | |

| 0 | None | |

| 1 | Patient is tearful (tearing up) | |

| 2 | Patient is crying | |

| 8. Sweating (observation/question) | 0.81 | |

| 0 | No sweat visible | |

| 1 | Feel Warm (Do you feel warm?) | |

| 2 | Barely perceptible sweating, palms moist (Do your palms feel clammy?) | |

| 3 | Beads of sweat obvious on forehead (Do you feel sweaty?) | |

| 9. Stomach/abdominal changes (question) | 1.00 | |

| 9a. | Do you feel sick to your stomach? | |

| 9b. | Do you feel butterflies in your stomach? | |

| 9c. | Do you feel tightness in your stomach? | |

| 9d. | Do you feel cramps in your stomach? | |

| 9e. | Do you feel heaviness in your stomach? | |

NA (Not Applicable): For item 3, one of the raters coded all of the participants as “zero” on this item. An accurate ICC score could not be calculated because the scores for one rater had no variation.

The content of the BAS was developed based on Lang's theory that emotions encompass behavioral and bodily sensations in addition to subjective, cognitive, and physiological action states (Lang, 1979). Many of the items were taken from Lang and colleague's list of physical and behavioral arousal responses provided in the “Scene Construction Questionnaire” (Miller et al., 1987). In addition, to be appropriate for the study of substance abusing populations, items associated with both emotional arousal and alcohol and drug withdrawal, including muscle ache and headache were added from the CIWA (Sullivan et al., 1989) and the CINA (Peachey and Lei, 1988).

The BAS can be scored as a count of behaviors or as a severity score (a sum of the severity ratings for each item). The present study used the severity score, however analyses with the count score showed the same pattern of findings. The internal consistency of the BAS severity score in the current study was adequate (α=0.62). To assess inter-rater reliability of the BAS, a second assistant attended the laboratory sessions for 17 participants (10.3%) and rated the participant on the BAS. Inter-rater reliability for the behavior severity scores was good (Mean intraclass correlation coefficient=0.85, see Table 2). BAS ratings were conducted at baseline (−5 min), immediately following imagery exposure (0 timepoint) and at +15 min after imagery.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics for alcohol dependent, cocaine dependent and healthy control participants

| Alcohol dependent (n=52) | Cocaine dependent (n=45) | Healthy control (n=68) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years: mean (SD)* | 38.19 (7.76) | 38.55 (5.52) | 30.96 (8.96) |

| Gender: number female (%)* | 10 (19.2%) | 22 (48.9%) | 34 (50.0%) |

| Race: Number (%)* | |||

| Caucasian | 38 (73.1%) | 18 (40.0%) | 41 (60.3%) |

| African American | 12 (23.1%) | 26 (57.8%) | 17 (25.0%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (1.9%) | 0 | 7 (10.3%) |

| Other | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (2.2%) | 3 (4.4%) |

| Years of education: mean (SD)* | 12.79 (1.75) | 12.36 (1.25) | 15.09 (1.88) |

| Lifetime psychiatric disorders: number (%) | |||

| Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | 2 (3.9%) | 4 (2.4%) | 3 (1.8%) |

| Anxiety disorder without PTSD* | 2 (3.85%) | 8 (17.78%) | 0 |

| Unipolar mood disorder | 7 (13.46%) | 5 (11.11%) | 4 (5.9%) |

| Alcohol use behavior | |||

| Current alcohol dependence: number (%)* | 52 (100.00%) | 12 (26.67%) | 0 |

| # Days drank in past month: mean (SD)* | 19.12 (9.76) | 9.11 (8.84) | 4.46 (5.55) |

| # Years using alcohol: mean (SD)* | 18.92 (8.44) | 14.95 (8.37) | 7.32 (7.66) |

| Cocaine Use Behavior | |||

| Current cocaine dependence: number (%)* | 14 (26.92%) | 45 (100.00%) | 0 |

| # Days used in past month: mean (SD)* | 4.63 (8.22) | 19.96 (8.90) | 0 |

| # Years using cocaine: mean (SD)* | 6.97 (6.32) | 10.51 (6.46) | 1.00 (1.00) |

| Smoking behavior | |||

| Smoker: number (%)* | 46 (88.46%) | 40 (90.91%) | 10 (14.7%) |

| # Cigarettes in past month: mean (SD)* | 450.61 (223.43) | 406.60 (243.34) | 240.73 (305.27) |

Indicates an overall significant group difference. Group differences were examined with Chi Square analyses for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

Subjective emotion experience

The Differential Emotions Scale-Revised short form (DES-R; Izard, 1972) was used as a measure of subjective emotional experience. The present study used five subscales from the original DES- anxiety, fear, sadness, anger, and joy and one subscale measuring participants' level of relaxation (sample items: at ease, calm) based on Izard (1972). Each subscale is made up of five adjectives describing the particular emotion state. Participants rate on a 5-point scale the extent to which each word describes the way they feel at the present moment. The DES shows good psychometric properties (Izard, 1972). Subjective emotion was assessed at several timepoints pre and post imagery exposure, but only the peak rating (0 timepoint) was included in the present study.

Alcohol or cocaine craving

The desire for using alcohol (for AD and HC participants) or for using cocaine (for COC participants) was assessed using a 10-point visual analog scale in which 1=“not at all” and 10=“extremely high”. Similar items phrased for alcohol and cocaine craving have been used in previous research and have been found to be associated with measures of alcohol and cocaine relapse factors (Breese et al., 2005; Sinha et al., 2006). Craving was measured at several timepoints, but only the peak rating (0 timepoint) was included in the present study.

Statistical analysis

Linear mixed effect modeling (LME; Laird and Ware, 1982) was used to test the first and second hypotheses that BAS scores would show increases in the stress condition as compared to the neutral condition for all groups (AD, COC, and HC) and would be higher in the addicted groups (AD, COC) than the healthy group (HC) following stress and drug cue exposure. A mixed design was used with Group (3: alcohol dependent, cocaine dependent, healthy controls) as the between subjects factor and Condition (stress, neutral/relaxing, cocaine or alcohol-cue) as a repeated measures factor. First, any group differences on baseline BAS scores were assessed using Group (healthy control, alcohol or cocaine dependent) as the fixed effects factors and subjects as the random effects factor. Second, response to each imagery condition was assessed. For response analyses, the Within-subjects factors of Condition (stress, neutral, alcohol cue), Time-point (−5, 0, +15), and the Between-subjects factors of Group (healthy controls, alcohol, or cocaine dependents) were the fixed effects and Subjects was the random effects factor. If there were significant group differences on baseline BAS scores, difference from baseline scores were used for the response analyses. In addition, we tested for group differences in demographic variables. All demographic variables that showed significant group differences were entered as control variables in the baseline analyses and the response analyses. If the variables were not significant predictors of BAS scores, they were then dropped from the final models.

Pearson correlations were performed to examine the third hypothesis that BAS response would be positively associated with other measures of subjective distress, including self-reported emotional arousal and craving. Correlations were performed using the peak scores (right after the imagery) for each measure in the stress and alcohol or cocaine cue conditions.

RESULTS

Demographics

Table 1 displays demographic, psychiatric history, and drug use information for the alcohol dependent (AD), cocaine dependent (COC), and healthy control (HC) participants. As shown in Table 1, there were group differences on every demographic variable and on lifetime history of non-PTSD anxiety disorders. To account for this, we entered race, gender, age, years of education, and lifetime anxiety disorders as covariates in the models predicting BAS scores. Race was a significant predictor of BAS scores at baseline and so it was retained in the baseline analysis. None of the covariates were significant predictors of BAS scores in the response analyses and so they were dropped from the response analyses.

BAS response to imagery exposure

Baseline analyses

There was a main effect of Group in baseline BAS scores (F[2,161]=7.54, p<0.001) with cocaine dependent participants greater than healthy participants (t[161]=3.77, p<0.001). Because of the group main effect on baseline scores, response analyses (below) examined difference from baseline scores.

Response analysis

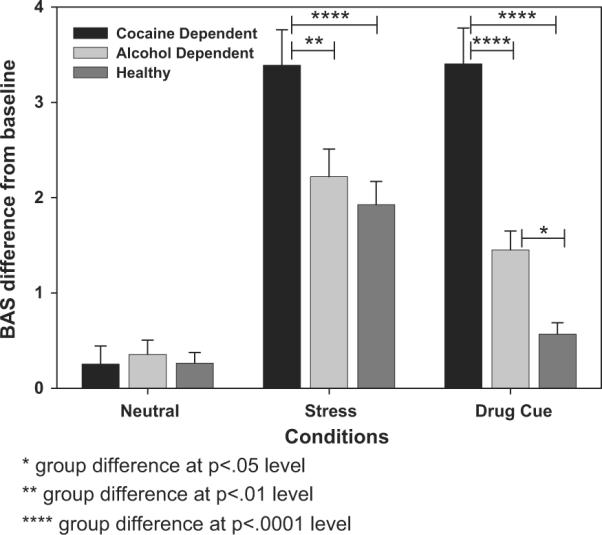

As predicted, a significant Group X Condition interaction (F[4, 323]=14.19, p<0.0001) was found (see Figure 1). Healthy controls showed greater behavioral response in the stress condition as compared to the alcohol/cocaine cue condition (t[323]=5.65, p<0.0001) and the neutral condition (t[323]=−6.97, p<0.0001), with no differences between the Neutral and cue conditions (t[323]=−1.29, ns). Alcohol dependent participants also showed greater behavioral response in the stress condition as compared to the cue condition (t[323]=2.82, p<0.01) and the neutral condition (t[323]=−10.69, p<0.0001). However, AD participants showed greater response in the cue than the neutral condition (t[323]=−4.02, p<0.0001). Cocaine dependent participants showed greater behavioral response in the stress condition as compared to the neutral condition (t[323]=−6.97, p<0.0001) and greater response in the cue condition than the neutral condition (t[323]=−10.62, p<0.0001). Interestingly, cocaine dependent participants showed no significant difference in response to the cue versus the stress condition (t[323]=0.03, ns). In sum, all groups showed elevated behavioral response to stress (as compared to the neutral condition) and dependent participants but not healthy participants showed elevated behavioral response to cue (as compared to neutral).

Figure 1.

Average BAS difference from baseline scores in neutral, stress and cue conditions by group (for Healthy Controls, Stress>Cue [p<0.0001] and Stress>Neutral [p<0.0001]; for Alcohol Dependents, Stress>Cue [p<0.01] and Stress>Neutral [p<0.0001] and Cue>Neu-Neutral [p<0.0001]; for Cocaine Dependents, Stress>Neutral [p<0.0001] and Cue>Neutral [p<0.0001])

Further, in the stress condition, COC participants had greater behavioral response than AD (t[323]=−3.18, p<0.01) and HC participants (t[323]=3.50, p<0.0001), with no differences between AD and HC participants (t[323]=0.54, ns). In the cue condition, COC participants had greater behavioral response than AD (t[323]=−5.30, p<0.0001) and HC participants (t[323]=7.02, p<0.0001), and AD had a greater response than HC participants (t[323]=2.18, p<0.05). In the neutral condition, there were no significant group differences. In sum, cocaine dependent participants showed the highest behavioral arousal of the three groups in response to stress and drug cue.

A significant main effect of condition was also found (F[2, 323]=106.50, p<0.0001) indicating a greater behavioral response across groups in the stress condition as compared to the neutral (t[323]=−14.29, p<0.0001) and the cue condition (t[323]=4.56, p<0.0001) and greater response in the cue condition as compared to the neutral condition (t[323]=−9.69, p<0.0001). A significant Group main effect (F[2, 157]=9.88, p<0.0001) indicated that the cocaine dependent group showed greater behavioral response than the alcohol dependent (t[157]=−3.55, p<0.001) and healthy controls (t[157]=4.14, p<0.0001) across conditions, with no significant differences between the AD and HC groups.

Correlations between BAS scores and emotional arousal and craving

As stated above, all correlation analyses used scores for each measure at the peak time point (directly following the imagery).

Stress condition

As shown in Table 3, in the stress condition, BAS scores were significantly positively correlated with measures of negative subjective emotions (anxiety, fear, sadness, anger), with medium sized correlation coefficients ranging from r=0.32–0.47. BAS scores were also significantly correlated with self-reported craving, with a small correlation coefficient (r=0.25) which is consistent with the notion that craving is associated with increased arousal. As expected, BAS scores were not correlated with subjective joy or relaxing state.

Table 3.

Correlations between BAS scores and measures of subjective emotion and craving in the stress condition

| BAS score | |

|---|---|

| 1. Subjective anxiety | 0.44**** |

| 2. Subjective fear | 0.32**** |

| 3. Subjective sadness | 0.47**** |

| 4. Subjective anger | 0.37**** |

| 5. Subjective craving | 0.25** |

| 6. Subjective joy | 0.14 ns |

| 7. Subjective “relaxed” | 0.03 ns |

ns is not significant.

p<0.01

p<0.0001.

Alcohol/cocaine cue condition

As shown in Table 4, in the cue condition, BAS scores were significantly correlated with measures of negative subjective emotion (anxiety, fear, sadness, and anger), with medium correlation coefficients ranging from r=0.37–0.57. BAS scores were also moderately correlated with reported craving (r=0.47). Notably, the correlations between the BAS and craving were of greater magnitude in the cue than the stress condition.

Table 4.

Correlations between BAS scores and measures of subjective emotion and craving in the alcohol/cocaine cue condition

| BAS score | |

|---|---|

| 1. Subjective anxiety | 0.57**** |

| 2. Subjective fear | 0.37**** |

| 3. Subjective sadness | 0.49**** |

| 4. Subjective anger | 0.48**** |

| 5. Subjective craving | 0.47**** |

| 6. Subjective joy | 0.11 ns |

| 7. Subjective “relaxed” | −0.02 ns |

p<0.0001

ns is not significant.

As expected, in the cue condition, BAS scores were not significantly correlated with subjective relaxing state (r=−0.02) or subjective joy (r=0.11).

DISCUSSION

The present study was the first to examine differences in behavioral and bodily signs of stress and arousal in cocaine dependent, alcohol dependent, and healthy adults in response to personalized stress and drug cue imagery. We found significant group differences in behavioral and bodily responses, as measured by our instrument, the behavioral arousal scale (BAS). The cocaine dependent individuals showed the highest behavioral arousal in response to stress, while both the cocaine and the alcoholic samples showed greater behavioral reactivity to drug cues than the healthy sample. These findings are consistent with growing evidence in support of protracted withdrawal-related changes in stress and reward pathways, which in turn, contribute to increased stress and cue reactivity and higher levels of drug craving in addicted samples (Koob and Kreek, 2007; Sinha, 2008). The current findings provide additional novel information regarding this increased stress system sensitivity by identifying the behavioral expression component of the stress experience as a significant domain of stress system alterations. These findings suggest that behavioral and/or bodily responses are important to measure in conjunction with subjective and physiological measures of emotional and craving-related arousal in laboratory studies of stress. Such behavioral and bodily signals of arousal could be of potential utility in assessing effectiveness of addiction treatments.

As predicted, BAS scores showed significant increases following stress as compared to a neutral (relaxing) imagery in all three groups, suggesting that the measure is indexing stress-related arousal. Thus, as predicted, the BAS measure reliably assessed the behavioral and bodily domain of emotional and stress-related arousal as outlined in emotion theories (e.g. Ekman and Davidson, 1994; Lang, 1979). Behavioral arousal was also increased following drug cue as compared to neutral imagery for the addicted groups, but not for the healthy participants. This is consistent with other research showing that cocaine and alcohol dependent individuals show heightened arousal responses to drug cue conditions as compared to healthy controls in their subjective negative emotion, autonomic response, and craving response (Fox et al., 2008; Sinha et al., 2009).

In addition, there were notable group differences in behavioral and bodily responses to stress and drug cues. Cocaine dependent participants had the greatest behavioral arousal in response to stress, greater than alcohol dependent and healthy control participants (who did not differ from one another). In addition, cocaine dependent participants had greater behavioral and bodily arousal in response to drug cue than alcohol dependent or healthy participants (although alcohol dependent did show greater behavioral response to cue than healthy participants). Taken together, this suggests that cocaine dependent individuals may be the most reactive behaviorally or in their body, more reactive even as compared to alcohol dependent individuals. Greater behavioral and bodily responses to distress in cocaine addicted individuals is consistent with an upregulated stress system in cocaine addiction, with documented alterations in both the HPA and autonomic nervous systems (Sinha, 2008). In contrast, alcohol dependent individuals show a blunted HPA axis response to stress (Adinoff et al., 2005; Breese et al., 2005; Junghanns et al., 2003; Lovallo et al., 2000), which may explain why they show lower behavioral and bodily response as compared to the cocaine dependent participants. However, even though they are decreased as compared to the cocaine dependents, alcohol dependent individuals showed equal behavioral and bodily response to stress as healthy controls and greater response to alcohol cue than healthy controls, suggesting that increased cue-related behavioral and bodily responses in alcohol dependent samples may be a valuable and unique index of a shift to negative reinforcement processes associated with conditioned alcohol cues in dependent versus non-dependent individuals (Sinha et al., 2009).

We also found that behavioral and bodily arousal scores were positively correlated with self-report measures of subjective negative emotional arousal following stress and drug cue exposure. The correlations were generally in the moderate range, suggesting that the Behavioral Arousal Scale (BAS) is related to negative emotional arousal, but is not redundant with self-report measures of emotion. This provides support for the validity of the BAS as a measure of negative arousal. The BAS also showed low to moderate correlations with craving (with higher correlations in the drug cue condition), which is consistent with previous cue reactivity models (Drummond et al., 1995; Tiffany and Conklin, 2000) and supporting empirical evidence which suggest higher levels of drug craving to be associated with greater stress and cue related arousal (Cooney et al., 1997; Fox et al., 2007, 2008; Sinha et al., 2009). Notably, BAS scores were not significantly correlated with self-reported joy or relaxation. Thus, the BAS showed some discriminant validity from measures of positive arousal states.

CONCLUSION

In sum, the current findings suggest that behavioral and bodily responses during both stress and drug cue exposure could represent a marker of the known alterations in stress and reward pathways among addicted individuals. Such findings, if validated in a larger sample of addicted individuals, may have clinical implications. For example, behavioral and bodily signs of distress may be assessed using the BAS in a clinical setting and those with greater distress symptoms may be assigned to more targeted stress related interventions to prevent relapse. Also, during the course of therapy, therapists could use the BAS to evaluate patients' progress. Patients might be more willing to admit to behavioral and bodily symptoms than they would be to admit that they are feeling emotional or are craving. Thus a therapist might be able to more accurately assess patients' functioning using the BAS than by using standard questions about their level of craving, for example. Then, therapists could use the BAS to track whether the patient has changed over the course of therapy and, if not, if the therapy approach should be adjusted.

One limitation to our study is that it cannot determine whether the heightened behavioral and bodily arousal in the addicted groups is due to effects of their previous use of substances or due to vulnerability factors present in childhood, before the development of substance abuse. Future longitudinal research could disentangle this. Despite this limitation, the present study demonstrated the importance of assessing behavioral and bodily signs of arousal in addicted populations. Further, the study presented a behavioral and bodily measure of distress in substance abusers that could be a marker of motivational “drive” associated with drug-seeking, and prove to be an easily quantifiable marker for treatment outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank research assistants at the Yale Stress Center for help in data collection and entry.

This study was supported by grants K01-DA024759 (Chaplin), R01-AA013892 (Sinha), P50-DA16556 (Sinha), UL1-RR024139 (Yale CTSA), and K02-DA17232 (Sinha) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and its Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH). The authors do not have a financial or personal relationship with the funding organization. Data in this manuscript have not been submitted for publication or presented elsewhere.

REFERENCES

- Adinoff B, Junghanns K, Kiefer F, Krishnan-Sarin S. Suppression of the HPA axis stress-response: implications for relapse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1351–1355. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000176356.97620.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SE, Brady KT, Jackson JL, Salstrom S, Zinzow H. Gender differences in stress reactivity among cocaine-dependent Individuals. Psychopharmacol. 2005;180:169–176. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychol Rev. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese GR, Chu K, Dayas CV, Funk D, Knapp DJ, Koob GF, Le DA, O'Dell LE, Overstreet DH, Roberts AJ, Sinha R, Valdez GR, Weiss F. Stress enhancement of craving during sobriety: a risk for relapse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:185–195. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000153544.83656.3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan D, Cisin IH, Crossley HM. American Drinking Practices: A National Study of Drinking Behavior and Attitudes (RCAS Monograph No. 6) Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies; New Brunswick, NJ: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Contoreggi C, Herning RI, Na P, Gold PW, Chrousos G, Negro PJ, Better W, Cadet JL. Stress hormone responses to corticotropin-releasing hormone in substance abusers without severe comorbid psychiatric disease. Biol psychiatry. 2003;54:873–882. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney NL, Litt MD, Morse PA, Bauer LO, Gaupp L. Alcohol cue reactivity, negative-mood reactivity, and relapse in treated alcoholic men. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106:243–250. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond DC, Tiffany ST, Glautier SP, Remington B. Cue exposure in understanding and treating addictive behaviours. In: Drummond DC, Tiffany ST, Glautier SP, Remington B, editors. Addictive Behaviour: Cue Exposure Theory and Practice. John Wiley; Chichester: 1995. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Davidson RJ. The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions. Oxford University Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- First MR, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Patient Edition American Psychiatric Press Inc.; Washington DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Bergquist KL, Hong K, Sinha R. Stress-induced and alcohol cue-induced craving in recently abstinent alcohol-dependent individuals. Alcohol: Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Hong K, Siedlarz K, Sinha R. Enhanced sensitivity to stress and drug/alcohol craving in abstinent cocaine-dependent individuals compared to social drinkers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:796–805. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE. Patterns of Emotions: A New Analysis of Anxiety and Depression. Academic Press; New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Junghanns K, Backhaus J, Tietz U, Lange W, Bernzen J, Wetterling T, Rink L, Driessen M. Impaired serum cortisol stress response is a predictor of early relapse. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003;38:189–193. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob G, Kreek MJ. Stress, dysregulation of drug reward pathways, and the transition to drug dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007:1149–1159. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.05030503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang P. A bio-informational theory of emotional imagery. Psychophysiol. 1979;16:496–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1979.tb01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Kozak MJ, Miller GA, Levin DN, McLean A., Jr. Emotional imagery: conceptual structure and pattern of somatovisceral response. Psychophysiol. 1980;17:179–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1980.tb00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, Barratt LF, editors. Handbook of emotions. The Guilford Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR, Dickensheets SL, Myers DA, Thomas TL, Nixon SJ. Blunted stress cortisol response in abstinent alcoholic and polysubstance-abusing men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:651–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Levin D, Kozak M, Cook E, McLean A, Lang P. Individual differences in imagery and the psychophysiology of emotion. Cogn Emot. 1987;1:367–390. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C. Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in adolescent females. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116:198–207. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ. Conditioning factors in drug abuse: can they explain compulsion? J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12:15–22. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peachey JE, Lei H. Assessment of opioid dependence with naloxone. Br J Addict. 1988;83:193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb03981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacol. 2001a;158:343–359. doi: 10.1007/s002130100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Imagery Script Development Procedures. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 2001b. Unpublished Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Behavioral Observation System. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 2004. Unpublished Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. The role of stress in addiction relapse. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9:388–395. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1141:105–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Fox HC, Hong KA, Bergquist K, Bhagwagar Z, Siedlarz KM. Enhanced negative emotion and alcohol craving, and altered physiological responses following stress and cue exposure in alcohol dependent individuals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1198–1208. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Garcia M, Paliwal P, Kreek MJ, Rounsaville BJ. Stress-induced cocaine craving and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses are predictive of cocaine relapse outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:324–331. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Lovallo WR, Parsons OA. Cardiovascular differentiation of emotions. Psychosom Med. 1992;54:422–435. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199207000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Parsons O. Multivariate response patterning of fear and anger. Cogn Emot. 1996;10:173–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Talih M, Malison R, Cooney N, Anderson GM, Kreek MJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sympatho-adreno-medullary responses during stress-induced and drug cue-induced cocaine craving states. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;170:62–72. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, Naranjo CA, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: The revised Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar) Br J Addict. 1989;84:1353–1357. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Dent CW, Galaif ER. The correlates of substance abuse and dependence among adolescents at high risk for drug abuse. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:241–255. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Conklin CA. A cognitive processing model of alcohol craving and compulsive alcohol use. Addiction. 2000;95:145–153. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanGoozen SH, Van de Poll NE, Sergeant JA, editors. Emotions: Essays on Emotion Theory. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Hirky AE. Coping and substance abuse: a theoretical model and review of the evidence. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS, editors. Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Application. Wiley and Sons; 1996. pp. 279–302. [Google Scholar]