Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To test the effects of maternal periodontal disease treatment on the incidence of preterm birth (delivery before 37 weeks of gestation).

METHODS

The Maternal Oral Therapy to Reduce Obstetric Risk Study was a randomized, treatment-masked, controlled clinical trial of pregnant women with periodontal disease who were receiving standard obstetric care. Participants were assigned to either a periodontal treatment arm, consisting of scaling and root planing early in the second trimester, or a delayed treatment arm that provided periodontal care after delivery. Pregnancy and maternal periodontal status were followed to delivery and neonatal outcomes until discharge. The primary outcome (gestational age less than 37 weeks) and the secondary outcome (gestational age less than 35 weeks) were analyzed using a χ2 test of equality of two proportions.

RESULTS

The study randomized 1,806 patients at three performance sites and completed 1,760 evaluable patients. At baseline, there were no differences comparing the treatment and control arms for any of the periodontal or obstetric measures. The rate of preterm delivery for the treatment group was 13.1% and 11.5% for the control group (P=.316). There were no significant differences when comparing women in the treatment group with those in the control group with regard to the adverse event rate or the major obstetric and neonatal outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Periodontal therapy did not reduce the incidence of preterm delivery.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

ClinicalTrials.gov, www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00097656.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE

I

Studies have suggested that maternal periodontal disease is associated with an increased risk for various obstetric and fetal complications including preterm delivery, very preterm delivery (less than 32 weeks of gestation), fetal growth restriction, and preeclampsia.1–14 A recent meta-analysis by Vergnes and Sixou that included 17 studies enrolling 7,151 women, 1,056 of whom delivered preterm neonates or low birth weight neonates or both,15 found that a pooled estimate for the risk of delivery at a gestational age of less than 37 weeks or having a neonate weighing less than 2,500 g or both in patients with periodontal disease was 2.83 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.95– 4.10, P<.001). However, the authors cautioned that additional high-quality studies are needed. Results from four randomized, single-center clinical trials suggest that periodontal treatment during pregnancy may reduce preterm births.16–19 However, results of a randomized, multicenter clinical trial show no difference between treatment and control groups for mean gestational age and for preterm birth at less than 37 weeks.20

The purpose of this article is to present the results of a large, randomized trial that tested the effects of maternal periodontal disease treatment on the incidence of preterm birth.

METHODS

The Maternal Oral Therapy to Reduce Obstetric Risk Study was a randomized, treatment-masked, controlled clinical trial of pregnant women with periodontal disease who were receiving standard obstetric care. Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory response to the tooth-associated microbial biofilm (plaque) that induces inflammation of the adjacent tissues and causes local tissue destruction and loss of the tooth attachment apparatus (ligament and bone). Bacterial biofilms begin on the crown (supragingival) and extend onto root surfaces under the gumline (subgingival) with penetration into the root surfaces and can become mineralized as hard deposits (calculus). Nonsurgical treatment of periodontal disease includes the mechanical removal of supragingival and subgingival microbial deposits and calculus by debridement using hand or ultrasonic instruments to remove bacteria and calculus and to plane the root surfaces to removed diseased and bacterially contaminated root surfaces. The study assessed the effects of nonsurgical periodontal therapy on rates of preterm delivery as the primary study outcome (defined as delivery at a gestational age of less than 37 weeks), as compared with a group who received periodontal care delayed until after delivery. All obstetric and dental examinations were performed by trained and calibrated obstetric and dental investigators. Safety oversight was provided by an independent data and safety monitoring board and the institutional review boards at each participating center. All participants provided written informed consent. Enrollment occurred between December 2003 and October 2007.

Patients were enrolled at Duke University Medical Center and the affiliated clinic at Lincoln Health Center, the University of Alabama at Birmingham Medical Center, and two obstetric sites of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (University Health Center-Downtown of University Health Systems and Salinas Clinic of the San Antonio Metropolitan Health District). Pregnant women presenting for obstetric care who were of legal age to consent and who were able to complete periodontal treatment before 23 6/7 weeks of gestation were recruited and screened for periodontal and obstetric eligibility. To be eligible, women had to have at least 20 teeth and at least three periodontal sites with at least 3 mm of clinical attachment loss. Before randomization, women could receive limited dental care to reduce the likelihood of an acute infectious event during pregnancy. These limited treatments included the extraction of hopeless teeth and restoration of pulp-threatening caries.

Gestational age was determined by ultrasound examination performed before 16 weeks. Women were excluded if they had multiple gestation; history of human immunodeficiency virus infection, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, autoimmune disease, or diabetes (gestational diabetes was acceptable); need for antibiotic prophylaxis for periodontal probing or periodontal treatment; or any obstetric finding that precluded enrollment in the study. Women with advanced caries or advanced periodontal disease requiring multiple immediate extractions were excluded.

Eligible participants were assigned randomly to receive periodontal treatment either before 23 6/7 weeks gestational age or after delivery. A permuted block randomization scheme with a random mixture of block sizes was used, stratifying participants by clinical center. Dental examiners were masked to treatment assignment of participants until after the postpartum examination, after the primary obstetric outcome was collected. This was achieved by using different staff members for examinations and therapy. Different examination and treatment rooms were used, and schedules were staggered as much as possible. Dental therapists were instructed not to divulge treatment status to study staff assigned to postnatal data collection. Participants and staff were instructed to not inform the postpartum examiner of the pregnancy outcome. The managing physicians were totally unaware of oral treatment assignments or treatment appointments.

Participants received up to four sessions (mean 1.3, standard deviation ±0.4) of supragingival and subgingival scaling and root planing using hand and ultrasonic instruments to complete the baseline therapy. Local anesthesia was used as needed. Those in the treatment group also received full-mouth tooth polishing and oral hygiene home instructions. There were no follow-up periodontal treatment visits. After delivery, those in the delayed-treatment group received periodontal therapy at no cost.

The principal outcome (gestational age less than 37 weeks) included induced or spontaneous deliveries, fetal demise, and miscarriage but not therapeutic abortions. The study initially was planned with the primary outcome being the proportion of births with gestational age less than 35 weeks. Before the start of recruitment, the data and safety monitoring board recommended switching the primary outcome to births with gestational age less than 37 weeks to improve study power. This change did not involve changing the target sample size. Secondary outcomes included incidence of gestational age less than 35 weeks; mean birth weight among neonates adjusting for race, sex, and gestational age; and a composite measure of neonatal morbidity and mortality before discharge defined as fetal demise after randomization-neonatal death before discharge from hospital to home or chronic care, respiratory distress syndrome, proven sepsis, grade 3 or 4 intraventricular hemorrhage, or necrotizing enterocolitis requiring treatment. These data were collected from neonatal intensive care unit records as were data on congenital abnormalities.

Before study initiation, periodontal examiners were trained and calibrated to the reference examiner to quantify intraexaminer and interexaminer reliability of measuring periodontal soft and hard tissue indices in both a dental chair and hospital bed. Annual retraining sessions were held. Percentage agreements for probing depth and attachment loss measures within 1 mm ranged from 80.5% to 100%, Kappas ranged from 0.755 to 1.000, and intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from 0.892 to 1.000 (average 0.970). Intraexaminer Kappa scores between measurements made in the dental chair and the bed were 0.983 and 0.969 for probing depth and clinical attachment loss measures, respectively.

Sample size determination used data from the University of Alabama pilot trial17 and estimated a preterm (gestational age less than 35 weeks) birth rate of 6% in the delayed periodontal therapy group compared with 2% in the periodontal therapy group, assuming a loss to follow-up rate of 3% in each group. We added the 3% loss to follow-up rate to each group under an intent-to-treat assumption, with the further assumption that all individuals lost to follow-up had a preterm birth. In this situation, a sample size of 900 per treatment group would provide power of 91% to detect such a difference between the two treatment groups. After the data and safety monitoring board recommended changing the primary outcome from gestational age less than 35 weeks to gestational age less than 37 weeks without changing the sample size, we determined the detectable treatment effect, using the same assumptions as above, for several preterm rates in the delayed-treatment group. For rates of 12%, 16%, and 20%, we would have 90% power to detect differences of 5.1, 5.7, and 6.2 percentage points, respectively.

Dental examiners conducted comprehensive oral soft tissue (cancer screening) and periodontal examinations at baseline and delivery. After enrollment, women were followed up by obstetric surveillance through parturition, followed by a postdelivery dental follow-up and neonatal surveillance that included chart review after discharge. All reported and observed adverse events were documented on case-report forms describing onset, duration, severity, assessment of causality, and relationship to treatment intervention. Participants’ obstetric charts were reviewed weekly to collect adverse events and treatment provided (outside of routine). All neonatal discharge summary findings were collected to monitor any adverse neonatal morbidity such as neonatal sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis. Serious adverse events included preterm labor hospitalization, pre-term birth, birth with maternal or fetal indications, other hospitalizations, triage, stillbirth or spontaneous abortion, neonatal death, and congenital anomaly.

Two interim analyses for efficacy were conducted (after 600 and 1,200 completed pregnancies) using O'Brien-Fleming type boundaries as the decision criteria for efficacy. All analyses were performed using the intention-to-treat principle unless stated otherwise. A P of .05 was used as a cutoff for statistical significance. P-values were not adjusted for multiple testing. The primary outcome (gestational age less than 37 weeks) and the secondary outcome (gestational age less than 35 weeks) were analyzed using a χ2 test of equality of two proportions. Pregnancies that did not end in a live birth (such as miscarriages) were regarded as part of the unfavorable outcome (gestational age less than 37 weeks or less than 35 weeks). Differences in proportions in outcomes between the treated group and the control group were tested for statistical significance by χ2 or Fisher exact test. The primary analysis for whether birth weight among those neonates with gestational ages less than 37 weeks differed by treatment group used a Kruskal-Wallis test.

RESULTS

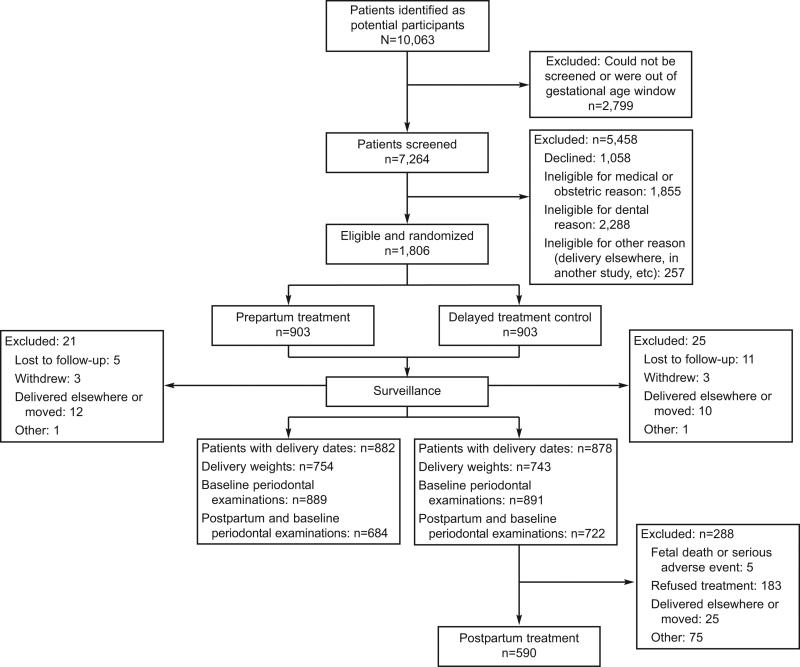

Of an estimated total patient pool of 29,000, 10,005 were invited to enroll, of whom 6,748 were potentially eligible and 1,806 were randomized (Fig. 1). Of those who were screened, there were 1,884 medically ineligible and 1,568 dentally ineligible. Randomizations occurred from February 2004 to September 2007. Approximately equal numbers of randomized participants in the two groups provided follow-up data for all outcomes, although 31.3% of those in the delayed treatment control group did not receive postpartum periodontal treatment for reasons shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Enrollment of Maternal Oral Therapy to Reduce Obstetric Risk Study patients. Offenbacher. Periodontal Treatment and Pregnancy Outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2009.

The treatment and control (delayed treatment) groups at baseline did not differ in maternal age, race, ethnicity, marital status, education, insurance or public assistance, maternal weight or height, or mean gestational age at randomization (19 5/7±2 1/7 weeks, Table 1). Similarly, the groups did not differ in parity, previous pregnancy histories, self-reported drug use, or smoking history; however, the treatment group reported significantly higher alcohol use during pregnancy. With respect to periodontal status, both groups had similar numbers of teeth, mean bleeding on probing scores, and extent of sites with at least 4 mm of probing depth. The overall randomization resulted in no significant differences in baseline characteristics comparing treatment with control groups, and this was also valid for each performance site, except that the number of nulliparous pregnancies was slightly higher among the group randomized to treatment at the North Carolina site (29.8% compared with 20.9%, treatment compared with control, respectively, data not shown).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristic by Treatment Group

| Characteristic | Control Group (n=903) | Treatment Group (n=903) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 902 (25.4±5.5) | 903 (25.3±5.5) | .869 |

| Race | |||

| White | 552/900 (61.3) | 545/897 (60.8) | .336 |

| African American | 332/900 (36.9) | 343/897 (38.2) | |

| Other | 16/900 (1.8) | 9/897 (1.0) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 420/902 (46.6) | 442/903 (49.0) | .311 |

| Hispanic | 482/902 (53.4) | 461/903 (51.1) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 435/902 (48.2) | 459/903 (50.8) | .854 |

| Widowed | 3/902 (0.3) | 3/903 (0.3) | |

| Married/partner | 431/902 (47.8) | 408/903 (45.2) | |

| Divorced | 14/902 (1.6) | 14/903 (1.6) | |

| Separated | 19/902 (2.1) | 19/903 (2.1) | |

| Education (y) | |||

| None | 5/900 (0.6) | 4/903 (0.4) | .472 |

| Elementary (1–6) | 71/900 (7.9) | 75/903 (8.3) | |

| Junior high school (7–8) | 62/900 (6.9) | 84/903 (9.3) | |

| High school (9–12) | 558/900 (62.0) | 528/903 (58.5) | |

| College (13–16) | 177/900 (19.7) | 184/903 (20.4) | |

| Graduate (17+) | 27/900 (3.0) | 28/903 (3.1) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 65/888 (7.3) | 72/893 (8.1) | .838 |

| Medicaid | 562/888 (63.3) | 559/893 (62.6) | |

| No insurance | 261/888 (29.4) | 262/893 (29.3) | |

| Receiving public assistance | |||

| Yes | 638/898 (71.0) | 611/898 (68.0) | .166 |

| No | 260/898 (29.0) | 287/898 (32.0) | |

| Maternal weight prepregnancy (kg) | 852 (69.5±19.1) | 830 (69.1±18.9) | .676 |

| Maternal height (cm) | 884 (159.7±7.8) | 885 (160.0±7.7) | .351 |

| Mean gestational age at randomization (wk) | 903 (19 5/7±2 1/7) | 903 (19.6±2.2) | .901 |

| Previous pregnancy classification | |||

| Any pregnancy | 710/902 (78.7) | 688/899 (76.5) | .266 |

| Full-term birth | 587/902 (65.1) | 593/899 (66.0) | .693 |

| Preterm birth | 96/902 (10.6) | 81/899 (9.0) | .244 |

| Previous abortions | 277/902 (30.7) | 246/899 (27.4) | .118 |

| Live births | 627/902 (69.5) | 622/899 (69.2) | .881 |

| Gravida | 903 (1.7±1.5) | 902 (1.6±1.5) | .770 |

| Parity | 903 (1.2±1.1) | 902 (1.2±1.2) | .497 |

| Self-reported street drug use during pregnancy* | 14/901 (1.6) | 17/901 (1.9) | .587 |

| Self-reported alcohol use during pregnancy* | 34/902 (3.8) | 54/903 (6.0) | .029 |

| Self-reported smoking during pregnancy* | 87/902 (9.7) | 98/903 (10.9) | .398 |

| Dental status at baseline | |||

| Percentage of tooth sites that bled on probing | 891 (45.2±27.0) | 890 (47.1±26.3) | .149 |

| Percentage of tooth sites with probing depth of at least 4 mm | 891 (26.1±15.5) | 890 (26.6±15.7) | .465 |

Data are n/total n (%) or n (mean±standard deviation) unless otherwise specified.

Self-reported data reporting of any drug, alcohol, or smoking use during pregnancy are based on self report at either baseline or postpartum examination interview.

Overall, there were no significant differences comparing women in the treatment group with those in the control group with regard to the major obstetric and neonatal outcomes of interest (Table 2). Primary outcome data (gestational age less than 37 weeks) are displayed in two ways: one considering missing data to be preterm delivery and the other in which the missing data are omitted (not intent-to-treat). There were no differences between those in the treatment and control groups in either of these analyses. For intent-to-treat analyses, the odds ratios (ORs) for gestational age less than 37 were 1.219 (95% CI 0.0893–1.664), for gestational age less than 35 0.998 (95% CI 0.640 –1.554), and for gestational age less than 32 1.138 (95% CI 0.637–2.033). Similarly, there were no differences between those in the treatment and control groups for secondary outcomes including mean birth weight, distribution of low birth weight categories, Apgar scores, neonatal intensive care unit admissions, rate of prematurity at gestational ages less than 35 weeks and less than 32 weeks, and incidence of preeclampsia. The ORs for intrauterine growth restriction were 0.801 (95% CI 0.604 –1.062), for birth weights less than 2,500 1.008 (95% CI 0.716 –1.419), and for birth weights less than 1,500 1.148 (95% CI 0.543–2.428).

Table 2.

Birth Outcomes

| Characteristic | Control Group | Treatment Group | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of pregnancy | |||

| Primary outcome | |||

| Less than 37 wk (missing considered preterm) | 104/903 (11.5) | 118/903 (13.1) | .316 |

| Less than 37 wk (missing not included) | 81/880 (9.2) | 97/882 (11.0) | .212 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Less than 35 wk | 41/880 (4.7) | 41/882 (4.6) | .992 |

| Less than 32 wk | 22/880 (2.5) | 25/882 (3.0) | .663 |

| Mean birth weight (g) GA less than 37 wk | 79 (2,027±810) | 94 (2,118±803) | .438 |

| Composite outcome of neonatal morbidity and mortality* | 41/878 (4.7) | 39/882 (4.4) | .803 |

| Other outcomes | |||

| Birth weight GA less than 37 wk adjusting for race, sex, and GA | 78 (2,085±38.6)* | 92 (2,080±35.4)* | .923 |

| Mean birth weight (g) GA more than 37 wk | 796 (3,333±488) | 784 (3,344±478) | .863† |

| Birth weight (excludes miscarriages/stillbirths) | |||

| Total birth weight (g) | 866 (3,241±590) | 872 (3,227±612) | .694 |

| Less than 2,500 g | 71/866 (8.2) | 72/872 (8.3) | .965 |

| Less than 1,500 g | 13/866 (1.5) | 15/872 (1.7) | .717 |

| Small for gestational age (10th percentile) | 119/867 (13.7) | 98/872 (11.2) | .117 |

| Birth length (cm) | 842 (49.6±3.5) | 842 (49.6±3.5) | .826† |

| Apgar score at 5 min | |||

| 0–3 | 6/852 (0.7) | 5/857 (0.6) | .627 |

| 4–7 | 25/852 (2.9) | 21/857 (2.5) | |

| 8–10 | 821/852 (96.4) | 831/857 (97.0) | |

| Admission to neonatal intensive care unit | |||

| Total number admitted | 85/873 (9.7) | 84/877 (9.6) | .911 |

| Length of stay more than 2 d | 71/83 (85.5) | 62/76 (81.6) | .500 |

| Discharged alive | 84/85 (98.8) | 78/81 (96.3) | .289 |

| Live births | |||

| Preterm | 871/880 (99.1) | 874/881 (99.2) | .614 |

| Less than 32 wk | 14/871 (1.6) | 20/874 (2.3) | .305 |

| Less than 35 wk | 33/871 (3.8) | 36/874 (4.1) | .727 |

| Less than 37 wk | 73/871 (8.4) | 91/874 (10.4) | .148 |

| Preeclampsia | 74/882 (8.4) | 67/880 (7.6) | .548 |

GA, gestational age.

Data are n/total n (%) or n (mean±standard deviation) unless otherwise specified.

Includes fetal demise after randomization, neonatal death before discharge, respiratory distress syndrome, proven sepsis, intraventricular hemorrhage grades III and IV, necrotizing enterocolitis requiring treatment, and congenital abnormalities.

Based on Kruskal-Wallis test.

Changes in periodontal status are given in Table 3. There was a significant worsening of periodontal status among patients in the delayed treatment (control) group. For example, there was an increase in overall mean probing depths of 0.23±0.02 mm among those in the control group. However, there was a significant interaction effect between all probing-depth measures and clinical center. In Alabama and North Carolina, both the control and treatment groups got worse (positive change score), with the control group having a statistically greater mean change in probing depth (P<.001 and P<.022, respectively). In Texas, periodontal status of the control group changed little during the study, and the treatment group improved (negative change score), resulting in a significant difference between groups (P<.001). The changes in percentage of sites with probing depths of 4 mm or more present a similar pattern of change. However, the percentage of sites with probing depths of 5 mm or more decreased in the treatment groups at Alabama and Texas, whereas both groups in North Carolina increased. There was no center interaction effect for attachment level and bleeding on probing measurements, with both measures being significantly better in the treatment group as compared with the control group (P=.005 and P<.001, respectively).

Table 3.

Mean Change in Periodontal Status During the Study

| Periodontal Measures* | Control Group | Treatment Group | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean change in probing depth (mm) | 728 (0.23±0.017) | 689 (0.03±0.018) | † |

| Alabama | 223 (0.28±0.030) | 199 (0.04±0.032) | <.001 |

| North Carolina | 250 (0.34±0.028) | 240 (0.25±0.029) | .022 |

| Texas | 255 (0.07±0.027) | 250 (–0.20±0.027) | <.001 |

| Mean change in percentage of sites with probing depth at least 4 mm | 728 (7.81±0.559) | 689 (1.40±0.574) | ‡ |

| Alabama | 223 (12.08±1.049) | 199 (4.35±1.1108) | <.001 |

| North Carolina | 250 (10.61±0.905) | 240 (7.79±0.923) | .030 |

| Texas | 255 (1.32±0.751) | 250 (–7.10±0.758) | <.001 |

| Mean change in percentage change with probing depth at least 5 mm | 728 (2.35±0.392) | 689 (–1.80±0.403) | § |

| Alabama | 223 (0.14± 0.875) | 199 (–6.13±0.926) | <.001 |

| North Carolina | 250 (5.29±0.584) | 240 (3.07±0.896) | .008 |

| Texas | 255 (1.40±0.494) | 250 (–3.03±0.499) | <.001 |

| Mean change in attachment level | 728 (–0.01±0.019) | 689 (–0.10±0.020) | .002 |

| Mean change in percentage bleeding on probing | 728 (4.48±0.936) | 689 (–7.85±0.963) | <.001 |

Data are number (mean±standard deviation) unless otherwise specified.

Negative numbers indicate improvement.

Significant interaction effect between treatment and clinic (P=.005).

Significant interaction effect between treatment and clinic (P=.003).

Significant interaction effect between treatment and clinic (P=.011).

The data in Table 3 show that treatment effects on periodontal status varied among centers and that the restoration of periodontal health may not have been achieved. Therefore, we conducted a non–intent-to-treat analysis to investigate the proportion of women meeting various definitions of periodontal health. These definitions were chosen a priori to evaluate the effectiveness of the periodontal therapy. Table 4 presents the number and percentage of women meeting various definitions of periodontal health at baseline and delivery. At baseline, no women met the definition of having all periodontal pockets less than 4 mm; at delivery, four women in the control group (0.5%) and seven in the treatment group (1.0%) met the criterion (P=.32). For periodontal pockets less than 5 mm, more women in the control group met the definition at baseline than at delivery, with the treatment group displaying the opposite pattern (P=.02). Aproximately 12–18% of women in both groups had less than 10% of sites with bleeding on probing at delivery. We also defined periodontal health as a shallow probing depth (3 mm or less) in the relative absence of bleeding on probing (less than 10%). Very few women met this stringent criterion. Because a previous study linked incidence or progression of probing depth to increased risk of preterm birth,21 we used the same definition of disease progression in this analysis. Among women in the control group, 30.5% had no progression during pregnancy compared with 40.7% in the treatment group. In summary, although the treatment group had less postpartum periodontal disease than did the control group, only a small proportion of the treatment group achieved what would be considered periodontal health, and we failed to arrest disease progression between baseline and delivery in 40.7% of the treatment group.

Table 4.

Number and Percentage of Women With Baseline and Delivery Periodontal Health by Treatment Group

| Control Group |

Treatment Group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Various Definitions of Periodontal Health | Baseline | Delivery | Baseline | Delivery |

| All periodontal pockets less than 4 mm | 0/728 (0.0) | 4/728 (0.5) | 0/691 (0.0) | 7/691 (1.0) |

| All periodontal pockets less than 5 mm | 70/728 (9.6) | 68/728 (9.3) | 58/691 (8.4) | 91/691 (13.2) |

| Bleeding on probing in 10% of sites or less | 75/728 (10.3) | 88/728 (12.2) | 69/691 (10.0) | 122/691 (17.7) |

| Periodontal pockets 3 mm or less and bleeding on probing 10% or less | 0/728 (0.0) | 2/728 (0.3) | 0/691 (0.0) | 5/691 (0.7) |

| No incidence or progression of pocket depth during pregnancy* | 410/691 (59.3) | 506/728 (69.5) | ||

Data are number/total number (%).

A person with progression is defined as four or more sites with pockets increasing by at least 2 mm resulting in a pocket depth of at least 4 mm.

There was no significant difference in the frequency of control and treatment group participants with serious adverse events. There were 119 (13.4%) participants reporting one or more serious adverse events among those randomized to treatment (total n=887) and 101 (11.4%) among those in the control group (total n=884), P=.20 (χ2). Comparing the two groups (n events treatment group/n events control group), there were no significant differences in the observed outcomes of serious adverse events, which included preterm labor hospitalization (15/15), pre-term birth (36/34), birth with maternal or fetal indications (40/34), other hospitalizations (35/25), triage (8/3), stillbirth or spontaneous abortion (7/7), neonatal death (4/2), and congenital anomaly (15/12).

DISCUSSION

Although the periodontal therapy resulted in a small but statistically significant improvement for many periodontal clinical signs relative to the delayed-treatment group, periodontal treatment did not restore most participants to periodontal health. The results from this study are in general agreement with previous findings of the Obstetrics and Periodontal Therapy study,20 which demonstrated that periodontal therapy during pregnancy did not alter the rates of preterm birth, low birth weight, or fetal growth restriction. So, what factors may explain the lack of any effect of this periodontal intervention on pregnancy outcomes?

One explanation is that periodontal disease does not influence preterm birth rates; the accumulated evidence to date has not been sufficient to conclude that periodontal disease is a cause or even an effect modifier in combination with other factors for pre-term birth. A second explanation may be that periodontal disease does increase the risk for preterm birth, but treatment of this exposure does not reduce that risk. Stamilio et al, commenting on a meta-analysis of studies on periodontal disease and preterm birth, notes that causation and treatment efficacy can be interrelated or they can function independently.22 For example, bacterial vaginosis is considered to be one contributing cause of preterm birth, yet antibiotic treatment of bacterial vaginosis in controlled trials did not reduce the risk of prematurity.23 At this point, there is not sufficient evidence to determine whether periodontal disease simply does not increase risk for preterm birth or whether it does increase risk but treatment as performed in this study was ineffective in decreasing preterm birth. This is in contrast to the recent meta-analysis by Polyzos etal,24 which includes data from seven trials including the large OPT trial. This meta-analysis concludes that periodontal therapy reduces the risk of preterm birth for gestational age less than 37 weeks (overall OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.35–0.86, P=.008, n=2,527 births). Further, the greatest benefit was seen among patients with less periodontal disease at baseline and no previous preterm deliveries, suggesting that prevention or other modalities of intervention including preconception or intraconception may be more efficacious rather than treatment of severe disease during pregnancy, such as in this study.

A third possibility is that preterm birth and periodontal disease both share a common underlying condition or trait, for example, an exaggerated inflammatory response that might explain the clinical response to the oral infection and the inflammatory process associated with obstetric complications. In this type of model, periodontal disease would contribute to the inflammatory burden and may be an effect modifier for the relationship between other conditions and the outcome (eg, subclinical vaginosis and preterm birth).

Any randomized, controlled trial assumes that the treatment provided is successful in reducing the level of the exposure. However, the treatment of periodontal disease is not always successful, and pregnancy itself poses an additional risk for periodontal disease onset and progression.21 Thus, a fourth possibility is that the periodontal intervention itself was not successful in returning the study participants to a healthy periodontal status. The data shown in Table 4 illustrate this point using definitions of periodontal health that have been published previously.25 In the Oral Conditions and Pregnancy Study,26 we identify maternal periodontal progression (as defined in Table 4) as the strongest periodontal indicator for prematurity. In the present study, 40.7% of the treatment group demonstrated progression. Bleeding on probing levels, which are a marker of potential systemic infectious exposure, and disease activity are high in both groups. These findings suggest that a single treatment employing only scaling and root planing was not adequate to control gingival inflammation between baseline and delivery.

Finally, there are striking analogies between the findings of the larger randomized controlled trials to treat periodontal disease and those targeting bacterial vaginosis. Both exposures represent putative risk factors in many but not all studies and appear as opportunistic biofilm infections dominated by anaerobic gram-negative bacteria. There is ample evidence of periodontal pathogens such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Campylobacter rectus displaying placental tropism and creating fetal exposure in utero.27 The biologic plausibility of the potential role of these organisms in mediated pregnancy and neonatal development pathologies is well established; however, trials designed to reduce or eliminate these infections appear to have been ineffective. Randomized controlled trials that more effectively control the micro-biome of the oral and reproductive tract are necessary to better control the role of this potentially noxious maternal–fetal burden.

Periodontal therapy as provided in this protocol did not reduce the incidence of preterm delivery at less than 37, 35, or 32 weeks of gestational age, weight for gestational age, or neonatal morbidity. Periodontal therapy consisting of a single treatment of scaling and root planing and oral hygiene instruction was ineffective in resolving gingival inflammation and preventing disease progression in the majority of these pregnant women.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIDCR grant U01-DE014577 and NCRR grants RR00046 and UL1RR025747.

Footnotes

For a listing of the MOTOR data managing and programming, clinical coordinator, and managerial staff who participated in this study, see the Appendix online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/A123.

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Offenbacher S, Beck JD, Lieff S, Slade G. Role of periodontitis in systemic health: spontaneous preterm birth. J Dent Educ. 1998;62:852–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1500–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu VY. Developmental outcome of extremely preterm infants. Am J Perinatol. 2000;17:57–61. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Kirmeyer S, et al. Births: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2007;56:1–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saling E. Prevention of prematurity. A review of our activities during the last 25 years. J Perinat Med. 1997;25:406–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mozurkewich EL, Naglie G, Krahn MD, Hayashi RH. Predicting preterm birth: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1589–98. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tocharoen A, Thompson S, Addy C, Sargent R, Best R, Shoob H. Intergenerational and environmental factors influencing pregnancy outcomes. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:475–6. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer MS, Séguin L, Lydon J, Goulet L. Socio-economic disparities in pregnancy outcome: why do the poor fare so poorly? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2000;14:194–210. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2000.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawoyin TO. The relationship between maternal weight gain in pregnancy, hemoglobin level, stature, antenatal attendance and low birth weight. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1997;28:873–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson KB, Willoughby RE. Infection, inflammation and the risk of cerebral palsy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2000;13:133–9. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200004000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leviton A, Paneth N, Reuss ML, Susser M, Allred EN, Dammann O, et al. Maternal infection, fetal inflammatory response, and brain damage in very low birth weight infants. Developmental Epidemiology Network Investigators. Pediatr Res. 1999;46:566–75. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199911000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cannon TD, Rosso IM, Bearden CE, Sanchez LE, Hadley T. A prospective cohort study of neurodevelopmental processes in the genesis and epigenesis of schizophrenia. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:467–85. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Popko B, Corbin JG, Baerwald KD, Dupree J, Garcia AM. The effects of interferon-gamma on the central nervous system. Mol Neurobiol. 1997;14:19–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02740619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hori T, Katafuchi T, Take S, Shimizu N. Neuroimmunomodulatory actions of hypothalamic interferon-alpha. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1998;5:172–7. doi: 10.1159/000026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vergnes JN, Sixou M. Preterm low birth weight and maternal periodontal status: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:135.el–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.López NJ, Smith PC, Gutierrez J. Periodontal therapy may reduce the risk of preterm low birth weight in women with periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2002;73:911–24. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.8.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeffcoat MK, Hauth JC, Geurs NC, Reddy MS, Cliver SP, Hodgkins PM, et al. Periodontal disease and preterm birth: results of a pilot intervention study. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1214–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadatmansouri S, Sedighpoor N, Aghaloo M. Effect of periodontal treatment phase I on birth term and birth weight. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2006;24:23–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.22831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarannum F, Faizuddin M. Effect of periodontal therapy on pregnancy outcome in women affected by periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78:2095–103. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michalowicz BS, Hodges JS, DiAngelis AJ, Lupo VR, Novak MJ, Ferguson JE, et al. Treatment of periodontal disease and risk of preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1885–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boggess KA, Beck JD, Murtha AP, Moss K, Offenbacher S. Maternal periodontal disease in early pregnancy and risk for a small-for-gestational-age infant. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1316–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stamilio DM, Chang JJ, Macones GA. Periodontal disease and preterm birth: do the data have enough teeth to recommend screening and preventive treatment? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:93–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonald H, Brocklehurst P, Parsons J. Antibiotics for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. The Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews 2005 , Issue 1. Art. No.: CD000262. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000262.pub2. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000262.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polyzos NP, Polyzos IP, Mauri D, Tzioras S, Tsappi M, Cortinovis I, et al. Effect of periodontal disease treatment during pregnancy on preterm birth incidence: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:225–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Offenbacher S, Barros SP, Singer RE, Moss K, Williams RC, Beck JD. Periodontal disease at the biofilm-gingival interface. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1911–25. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lieff S, Boggess KA, Murtha AP, Jared H, Madianos PN, Moss K, et al. The oral conditions and pregnancy study: periodontal status of a cohort of pregnant women. J Periodontol. 2004;75:116–26. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madianos PN, Lieff S, Murtha AP, Boggess KA, Auten RL, Beck JD, et al. Maternal periodontitis and prematurity. Part II: maternal infection and fetal exposure. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:175–82. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]