Abstract

OBJECTIVE

We estimated the efficacy of a psycho-behavioral intervention in reducing intimate partner violence (IPV) recurrence during pregnancy and postpartum, and in improving birth outcomes in African-American women

METHODS

We conducted a randomized controlled trial in which 1,044 women were recruited. Individually-tailored counseling sessions were adapted from evidence-based interventions for IPV and other risks. Logistic regression was used to model IPV victimization recurrence, to predict minor, severe, physical and sexual IPV.

RESULTS

Women randomized to the intervention were less likely to have recurrent episodes of IPV victimization (OR=0.48, 95%CI=0.29-0.80). Women with minor IPV were significantly less likely to experience further episodes during pregnancy (OR=0.48, 95%CI=0.26-0.86, OR=0.53, 95%CI=0.28-0.99) and postpartum (OR=0.56, 95%CI=0.34-0.93). Numbers needed to treat were 17, 12, and 22, respectively as compared to the usual care Women with severe IPV showed significantly reduced episodes at postpartum (OR=0.39, 95%CI=0.18-0.82) and number needed to treat is 27. Women who experienced physical IPV showed significant reduction at the first follow-up (OR=0.49, 95%CI=0.27-0.91) and postpartum (OR=0.47, 95%CI=0.27-0.82) and number needed to treat is 18 and 20, respectively. Intervention women had significantly fewer very preterm infants (p=0.03) and an increased mean gestational age (p=0.016).

CONCLUSION

A relatively brief intervention during pregnancy had discernable effects on IPV and pregnancy outcomes. Screening for IPV as well as other psychosocial and behavioral risks and incorporating similar interventions in prenatal care is strongly recommended.

BACKGROUND

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as a pattern of assaultive and coercive behaviors, that includes the threat or infliction of physical, sexual, or psychological abuse that is used by perpetrators for the purpose of intimidation of and/or control over the victim.1-3 There is no set agreement regarding what signs, symptoms or illnesses are considered the standard ICD-9 constellation for a diagnosis of IPV.4,5

The CDC reports that approximately 5.4 million episodes of IPV occur every year in the United States in women eighteen years and older. 6 The literature is inconsistent as to whether minorities are at increased risk, with some studies reporting significant differences7-10 and others finding no racial or ethnic differences.11,12 The most recent, largest and nationally representative study found no differences of lifetime prevalence for IPV by race/ethnicity, while the rate for the 12 months preceding the survey was almost twice as high among African-Americans.13 Although some authors link IPV to socio-economically deprived communities, it is by no means limited to the economically disadvantaged. Families with conflicting priorities and stressors associated with limited psycho-social reserves may be at greatest risk.14 Factors including housing conditions, poverty and street violence are associated with higher prevalence of violence inside the home environment. Political disenfranchisement and cultural isolation may also be mediators for IPV. Women living under such conditions are more likely to be victimized as compared to women living in more stable and better organized communities.15-17

PRÉCIS.

This randomized controlled trial of a cognitive/behavioral integrated intervention during pregnancy shows efficacy in reducing intimate partner violence victimization and improving pregnancy outcomes.

Exposure to IPV is associated with a range of negative psycho-behavioral risks as well as health outcomes including increased risk of poor physical health, physical disability, psychological distress, mental illness, and heightened substance use including alcohol and illicit drugs.18 Sexual and physical IPV have been linked significantly with depression, suicidality, and post traumatic stress disorder.19-22 Women who suffer from IPV are more likely to have sexually transmitted diseases, vaginal bleeding or infection and urinary tract infections.23 Abuse during pregnancy has been shown to be associated with significantly higher rates of depression, suicide attempts as well as use of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drugs.24-31 IPV has been linked to both pregnancy complications (e.g., inadequate weight gain, infections and bleeding) as well as adverse pregnancy outcomes (low birth weight (LBW), preterm delivery (PTB) and neonatal death).32-34 IPV amongst minority populations, already at higher risk for poor pregnancy outcomes, may be a significant contributor to the health disparities observed in reproductive outcomes amongst African-American women.

The objective of this paper is to estimate the efficacy of a cognitive behavioral intervention administered as part of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) during prenatal care (PNC) in reducing IPV recurrence during pregnancy and improving birth outcomes (LBW and PTB) in a population of African-American residents of Washington, DC.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

The “NIH-DC Initiative to Reduce Infant Mortality in Minority Populations” is a collaboration between Children's National Medical Center, Georgetown University, George Washington University Medical Center, Howard University, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities and RTI International. As part of this collaboration, we conducted a RCT to evaluate the efficacy of an integrated behavioral intervention delivered during PNC in reducing cigarette smoking, environmental tobacco smoke exposure (ETSE), depression and IPV during pregnancy and in improving pregnancy outcome. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions.

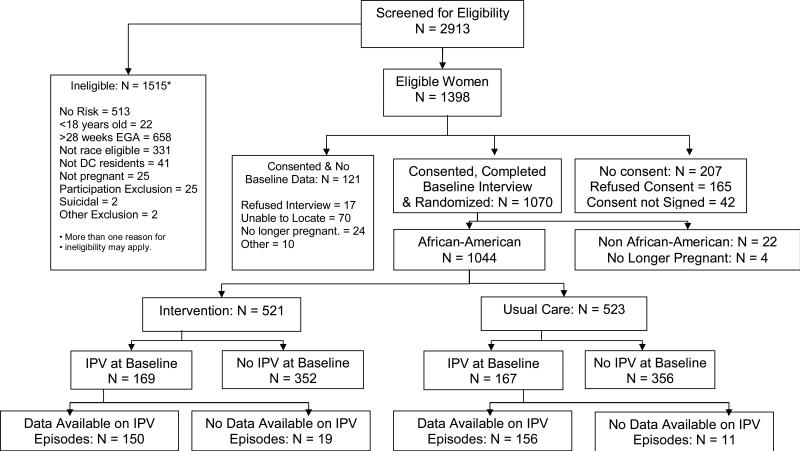

Women were screened at six community based PNC sites serving mainly minority women in the District of Columbia between July, 2001 and October, 2003. Women were demographically eligible if they self-identified as being a minority, were ≥18 years old, ≤28 weeks pregnant, a DC resident and English speaking. Almost two-thirds (63.4%) were recruited before 22 weeks gestation, 16.9% were recruited between 22 and 25 weeks gestation and 19.7% were recruited between 26 and 28 weeks gestation. The women who were demographically eligible were consented in a two-stage consent and enrollment process. After initial consent, participants were screened for the four risk factors (cigarette smoking, ETSE, depression, and IPV) using an audio-computer assisted self interview which also confirmed their demographic eligibility. An average of 9 days after screening, a baseline interview took place where more detailed information on socio-demographics, reproductive history and behavioral risks was collected. Following this interview, women were consented to participate. Follow-up data collection by telephone interviews occurred during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy (22-26 and 34-38 weeks gestation, respectively) and 8-10 weeks postpartum. Intervention and follow-up activities continued until July 2004. Details are published in El-Khorazaty et al.35 A total of 2,913 women were screened and 1,398 met eligibility criteria (See Figure 1). Of these 85% (n=1,191) consented to participate in a baseline telephone interview before randomization; 1,070 (89.9%) were reached and participated. Eligible women were randomized to the intervention group or usual care group. Of these women 1,044 were African-American and still pregnant at the time of the baseline interview. Included in the analyses were 521 randomized to the intervention and 523 randomized to usual care.

Figure 1.

Profile of Project DC-HOPE Randomized Controlled Trial

Women randomized to the intervention received an integrated cognitive behavioral intervention and women randomized to usual care received their usual prenatal care, as determined by the standard procedures at the PNC clinic. 336 women reported IPV victimization in the past year during the baseline interview and this group could be further categorized as having minor and/or severe IPV, physical and/or sexual IPV based on the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS).36 A woman may experience multiple types of violence; thus these categories are not mutually exclusive. Minor IPV was defined if the woman's partner slapped, grabbed, pushed, or shoved her, threw something at her, twisted her arm or hair, and insisted, without using force, on anal sex, intercourse, or sex without using a condom. Major IPV was defined if the woman's partner kicked, bit, punched, beat up, hit, choked or slammed her, used knife or gun, burned or scalded her on purpose, and used force or threats to have sex or anal sex. Physical IPV was defined if the woman's partner threw something at her, pushed or shoved her, used a knife or gun, hit, choked, slammed, grabbed, burned, or kicked her. Sexual assault was defined if the woman's partner forced sex without using a condom, forced her to have sex, threatened or insisted on having sex (oral, anal, or vaginal) against her will.

The intervention utilized in this RCT was delivered during routine PNC visits at the clinics by interventionists (master's level social workers or psychologists), trained specifically to deliver this intervention. The intervention was evidence-based and specific to each of the designated psycho-behavioral risks.37 At each intervention session the woman identified which of the four risks she was experiencing. The intervention was delivered by the interventionist and targeted to address all risks reported at each session, regardless of previously reported risks. The intervention for IPV emphasized safety behaviors and was based on the structured intervention developed by Parker and colleagues38 and based on Dutton's39 Empowerment Theory. This intervention provided information about the types of abuse (e.g., emotional, physical and sexual) and the cycle of violence (e.g., escalating, IPV, honeymoon period), a Danger Assessment Component to assess risks, and preventive options women might consider (e.g., filing a protection order) as well as the development of a safety plan (e.g., leaving important documents and papers with others). In addition, a list of community resources with addresses and phone numbers was provided. The intervention for smoking and ETSE were combined and based on Smoking Cessation or Reduction in Program Treatment. This intervention was cognitive-behavioral and based on a woman's stage of readiness for behavioral change.40 The depression intervention was developed by Miranda and Munoz 41 based on cognitive behavioral theory and focused on mood management, increasing pleasurable activities and increasing positive social interactions.

The components of the intervention were designed for delivery in a minimum of four sessions with eight prenatal sessions required for a complete intervention, based on the highest number of sessions required for a specific risk. Fifty-one percent of the women randomized to the intervention received four or more sessions, while one-quarter of the women attended no intervention sessions. Individualized counseling sessions provided an integrated approach to multiple risks responsive to a woman's specific risk combination. Two additional postpartum booster sessions were provided to reinforce risk-specific intervention goals and support women through the postpartum period. Intervention sessions were conducted privately in a room proximate to or within the PNC clinics and occurred immediately before or after routine PNC. Intervention activities addressing all of the individually identified risks at each session lasted for an average of 35+15 minutes. Women in the intervention received $10 for each intervention session and additional $15 and $25 gift certificates for the first and second postpartum intervention sessions, respectively.

During screening or follow-up, women reporting suicidal ideation were immediately referred to the mental health consultation team. Women were evaluated and referred, as necessary. Those found to be potentially suicidal (n=10) were excluded from the study.

The sample size was powered to test the reduction in psycho-behavioral risk, with the theory that a reduction in risk would help improve pregnancy outcomes. Assuming a 5% level of significance, 80% power would allow the detection of 10-20% reductions in risk-specific factors among women in the intervention from a prevalence of 100% at recruitment. A sample of 1,050 women needed to be retained at the end of the follow-up period (525 women in each of the intervention and usual care group). The anticipated number of women reporting IPV needed to detect significance in reducing risk was 337 split between the two care groups). This sample size was also sufficient to detect a 25% reduction in preterm birth and low birth weight combined in the intervention as compared to that for the usual care group (estimated at 20%). Based on a declining birth rate in D.C., the recruitment period was extended four months to reach the required sample size.

Site- and risk-specific permuted block randomization to the intervention or usual care was conducted. Both the investigators and the field workers were blinded to block size. A computer generated randomization scheme was utilized to consider all the possible risk combinations within each of the recruitment sites. When a woman completed the baseline interview and was ready for randomization, the recruitment staff would call the data coordinating center, where the subject's assignment was determined.

Validated instruments were used for each of the data collection time points. During screening, IPV was identified by the Abuse Assessment Screen, a measure designed and validated for use in pregnancy if a woman reported physical or sexual abuse by a partner in the previous year.42 During the baseline and follow-up interviews, the frequency of physical assault and sexual coercion (partner to self) was measured by the Conflict Tactics Scale.36 A more detailed description of instruments used for other risks is available in Katz et al.37

Telephone interviewers and their supervisors were blinded to the participants’ randomization group. Research staff maintained confidentiality when communicating with participants outside the clinic setting. Addresses were collected to facilitate tracing efforts, but the women were informed that they would not receive mail from Project DC-HOPE. For women experiencing IPV, staff did not want to raise women's risk for abuse by receiving mail from the study that might be negatively regarded by an abusive partner, or would expose her pregnancy. Women were also asked whether or not telephone messages from project staff could be left on their telephone answering machines. If not, this was noted in her computerized record accessible by all project teams. As financial incentives the women received $5 for the screening, a 30-minute telephone card for providing main study consent, and $15 for each telephone interview. At the time of recruitment medical records were abstracted and upon delivery data on infant and pregnancy outcomes were recorded.

To preserve the randomization, participant data were analyzed according to their care group assignment, regardless of receipt of intervention, using an intent-to-treat approach. All statistical analyses were conducting using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Bivariate analyses were conducted to compare the baseline characteristics and pregnancy outcomes of women assigned to the intervention versus usual care and to compare women who reported a recurrence of IPV during pregnancy or postpartum versus those who did not. T-tests compared groups based on continuous variables (using the TTEST procedure in SAS) and chi-square tests compared the groups with respect to categorical variables (using SAS's FREQ procedure). Logistic regression was used to model recurrence of IPV based on care group assignment, controlling for relevant covariates (using the LOGISTIC procedure). Logistic models were also created to predict minor, severe, physical and sexual IPV reported at each interview. Adjusted odd ratios (AOR) were produced by models that included care group plus other covariates.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics and psycho-behavioral risks at baseline between women randomized to the intervention (n=521) or usual care (n=523). There were no significant differences between these two groups. During the baseline interview, 336 women (32.2%) reported IPV in the previous year. Of these women 169 were in the intervention and 167 were in the usual care group (See Figure 1). In this subgroup, there were no significant differences between the women in the two randomization groups (See Table 1). Mothers were of 24.5 years mean age. On average participants initiated PNC at 13 weeks of gestation. Seventy-six percent were single, 68% had at least a high school education and 79% were enrolled in Medicaid. In this population, 22% of the mothers admitted to active smoking during pregnancy, 78% self-identified as being at risk for ETSE and 62% were depressed as measured by the Hopkins Scale. In addition, 32% admitted to using alcohol and 17% admitted to illicit drug use during pregnancy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of All Participants and those Acknowledging Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Victimization at Baseline

| Characteristic | Value | All Participants | Women with IPV at Baseline | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N=521) | Usual Care (N=523) | Intervention (N=169) | Usual Care (N=167) | ||

| Maternal age | Mean ± SD | 24.4±5.5 | 24.8±5.3 | 24.5±5.8 | 24.5±5.4 |

| Gestational age at enrollment (weeks) | Mean ± SD | 19.3±6.9 | 18.6±6.8 | 19.2±6.8 | 18.5±6.9 |

| Education level | < High school | 159 (30.5%) | 157 (30.0%) | 54 (32.0%) | 53 (31.7%) |

| HS graduate/GED | 245 (47.0%) | 241 (46.1%) | 77(45.6%) | 67 (40.1%) | |

| At least some college | 117 (22.5%) | 125 (23.9%) | 38 (22.5%) | 47 (28.1%) | |

| Employment status | Working now | 185 (35.5%) | 196 (37.5%) | 58 (34.3%) | 67 (40.4%) |

| Not working now, worked previous to pregnancy | 185 (35.5%) | 193 (36.9%) | 67 (39.6%) | 59 (35.5%) | |

| Not working now, did not work previous to pregnancy | 150 (28.8%) | 130 (24.9%) | 44 (26.0%) | 40 (24.1%) | |

| Relationship status | Single/separated/widowed/divorced | 396 (76.0%) | 401 (76.7%) | 132 (78.1%) | 122 (73.1%) |

| Married or living with partner | 125 (24.0%) | 122 (23.3%) | 37 (21.9%) | 45 (27.0%) | |

| Emotional support from partner | Mean ± SD | 36.9±20.6 | 37.3±20.5 | 32.8±20.9 | 32.7±19.7 |

| Emotional support from others | Mean ± SD | 39.4±15.1 | 40.8±14.7 | 37.7±14.9 | 39.3±14.9 |

| Emotional support from partner prior to delivery | Mean ± SD | 34.3±21.6 | 33.9±21.8 | 31.0±21.9 | 29.6±21.6 |

| Emotional support from others prior to delivery | Mean ± SD | 41.8±12.7 | 41.7±13.4 | 40.5±13.7 | 39.9±14.7 |

| Trimester of PNC initiation | 1st Trimester | 305 (61.6%0 | 300 (58.9%) | 94 (58.8%) | 98 (60.9%) |

| 2nd Trimester | 179 (36.2%) | 201 (39.5%) | 60 (37.5%) | 60 (37.3%) | |

| 3rd Trimester | 11 (2.2%) | 8 (1.6%) | 6 (3.8%) | 3 (1.9%) | |

| Medicaid | Yes | 411 (78.9%) | 402 (76.8%) | 134 (79.8%) | 129 (77.7%) |

| WIC | Yes | 226 (43.4%) | 228 (43.6%) | 74 (43.8%) | 76 (45.5%) |

| Supplemental food program | Yes | 369 (71.1%) | 382 (73.0%) | 168 (99.4%) | 162 (97.0%) |

| Public assistance/TANF | Yes | 213 (41.0%) | 223 (42.7%) | 73 (43.2%) | 69 (41.3%) |

| Alcohol use in this pregnancy | Yes | 111 (21.3%) | 112 (21.4%) | 58 (34.3%) | 49 (29.3%) |

| Illicit drug use in this pregnancy | Yes | 67 (12.9%) | 56 (10.7%) | 26 (15.4%) | 30 (18.0%) |

| Marijuana use | Yes | 62 (11.9%) | 52 (9.9%) | 23 (13.6%) | 28 (16.8%) |

| Cocaine use | Yes | 6 (1.2%) | 7 (1.3%) | 5 (3.0%) | 3 (1.8%) |

| Pregnancy 'wanted' | Yes | 403 (77.4%) | 395 (75.5%) | 127 (76.1%) | 117 (71.3%) |

| Previous pregnancy | Yes | 425 (81.6%) | 443 (84.7%) | 141 (83.4%) | 144 (86.2%) |

| Previous live birth | Yes | 173 (33.2%) | 163 (31.2%) | 112 (69.5%) | 116 (69.5%) |

| Number of live births (women with previous pregnancy) | Mean ± SD | 2.1±1.5 | 2.2±1.4 | 1.9±1.7 | 1.7±1.5 |

| Previous preterm delivery | Yes | 72 (14.2%) | 66 (12.7%) | 30 (22.2%) | 23 (16.4%) |

| Previous stillbirth, miscarriage and loss (women with previous pregnancy) | Yes | 181 (42.6%) | 192 (43.3%) | 59 (42.1%) | 68 (47.2%) |

| Gestational diabetes | Yes | 25 (5.8%) | 32 (7.0%) | 8 (5.6%) | 11 (7.5%) |

| Preconception diabetes | Yes | 19 (3.7%) | 18 (3.4%) | 7 (4.2%) | 4 (2.4%) |

| Gestational hypertension | Yes | 14 (3.3%) | 20 (4.4%) | 3 (2.1%) | 6 (4.1%) |

| Chronic hypertension | Yes | 31 (6.0%) | 29 (5.5%) | 13 (7.8%) | 5 (3.0%) |

| Active smoking at baseline | Yes | 106 (20.3%) | 92 (17.6%) | 38 (22.5%) | 36 (21.6%) |

| ETSE at baseline | Yes | 365 (71.4%) | 377 (73.3%) | 128 (77.1%) | 130 (78.8%) |

| Depression at baseline | Yes | 229 (44.0%) | 234 (44.7%) | 101 (59.8%) | 106 (63.5%) |

| IPV at baseline | Yes | 169 (32.4%) | 167 (31.9%) | --- | --- |

| Active smoking prior to delivery | Yes | 70 (16.6%) | 65 (15.2%) | 24 (17.8%0 | 26 (19.6%) |

| ETSE prior to delivery | Yes | 247 (58.7%) | 277 (65.2%) | 82 (61.2%) | 89 (66.9%) |

| Depression prior to delivery | Yes | 152 (35.9%) | 170 (39.8%) | 71 (52.6%) | 71 (53.4%) |

| Active smoking at postpartum | Yes | 89 (21.9%) | 106 (25.0%) | 31 (22..8%) | 44 (31.9%) |

| ETSE at postpartum | Yes | 196 (48.5%) | 233 (55.9%) | 63 ( 46.7%) | 85 (63.0%) |

| Depression at postpartum | Yes | 90 (22.2%) | 118 (27.8%) | 39 (28.9%) | 51 (37.0%) |

Notes: (1) PNC: prenatal care; WIC: Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infant and Children; TANF: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families; ETSE: Environmental Tobacco Smoke Exposure; IPV: Intimate Partner Violence

(2) All characteristics are measured at baseline except when noted otherwise.

Of those women reporting IPV at baseline, 306 women (91.1%) completed at least one of the follow-up or postpartum interviews. No significant differences were found between those with follow-up data (n=306) and those without (n=30), nor were women randomized to the intervention (n=150) significantly different from those randomized to the usual care (n=156).

Women reporting continued IPV during pregnancy or postpartum (n=94) were significantly different from those who reported no further episodes of IPV (n=212) beyond baseline with respect to care group (p=0.006), gestational age at baseline (p=0.035), alcohol use during pregnancy (p=0.014) and depression at baseline (p=0.009).

Controlling for these four variables in the logistic regression, only care group, alcohol use and depression were significant in the reduced model. Logistic regression results for continued IPV at all interviews during pregnancy and postpartum (n=94) showed that women in the intervention were less likely to have recurrent episodes of IPV (AOR=0.48, 95% CI=0.29-0.80). Alcohol use during pregnancy measured at baseline and depression were associated with the chance of recurrent episodes of IPV (AOR=1.85, 95% CI=1.09-3.12; AOR=1.90, 95% CI=1.11-3.25, respectively). Women in the intervention were less likely to be victimized by their partners at the first or second follow-up interviews (second or third trimester) (see Table 2). Although the trend remains, the difference does not reach significance in the postpartum period.

Table 2.

Comparison of Intervention and Usual Care Groups by Continued IPV

| Characteristic | Intervention | Usual Care | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPV Victim at FU1 | 14/92 (15.2%) | 32/105 (30.5%) | 0.012 |

| IPV Victim at FU2 | 10/110 (9.1%) | 20/110 (18.2%) | 0.050 |

| IPV Victim at PP | 17/134 (12.7%) | 29/137 (21.2%) | 0.063 |

| IPV Victim at All FU1, FU2 and PP | 35/150 (23.3%) | 59/156 (37.8%) | 0.006 |

Note: IPV: Intimate Partner Violence; U1: First Follow-up (22-26 weeks gestation) interview; FU2: Second Follow-up (34-38 weeks gestation) interview; PP: Postpartum interview

Table 3 presents adjusted odds ratios and numbers needed to treat for the impact of the intervention on minor IPV, severe IPV, physical IPV and sexual IPV at baseline and each of the follow-up interviews. It should be noted that reported IPV at baseline refers to the one year preceding the interview while at each of the three subsequent interviews, the reference period was since the previous interview, on average 9-10 weeks during pregnancy and 14 weeks between the second follow-up and the postpartum interview. At baseline no significant differences between groups were observed for any of these four categories. Women with minor IPV and randomized to the intervention were significantly less likely to experience further episodes at all of the follow-up points. Women categorized with severe IPV in the intervention, showed a significantly reduced incidence of episodes at postpartum, compared to the usual care group. Women experiencing physical IPV were significantly less likely to experience episodes at first follow-up or at postpartum interviews, compared to the usual care group. For women experiencing sexual IPV, the intervention did not significantly reduce their incidence of episodes at any follow-up visit during pregnancy or postpartum.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios* for the Impact of the Intervention on Various Categories of Intimate Partner Violence Victimization during Pregnancy and Postpartum

| Intervention vs. Usual Care |

Minor IPV |

Severe IPV |

Physical IPV |

Sexual IPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL: | ||||

| N (%) | 327 (31.4%) | 185 (17.7%) | 295 (28.3%) | 153 (14.7%) |

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.07 (0.81 – 1.40) | 0.97 (0.70 – 1.35) | 1.07 (0.81 – 1.42) | 1.03 (0.72 – 1.47) |

| Absolute Risk Difference** | 0.014 | 0.004 | 0.014 | 0.004 |

| Number Needed to Treat (95% CI)*** |

--- |

--- |

--- |

--- |

| FU1: | ||||

| N (%) | 56 (9.5%) | 24 (4.1%) | 52 (8.8%) | 22 (3.7%) |

| AOR (95% CI) | 0.48 (0.26 – 0.86) | 0.53 (0.22 – 1.27) | 0.49 (0.27 – 0.91) | 0.39 (0.15 – 1.03) |

| Absolute Risk Difference** | 0.061 | 0.024 | 0.054 | 0.031 |

| Number Needed to Treat (95% CI)*** |

17 (11 – 67) |

--- |

18 (12 – 108) |

--- |

| FU2: | ||||

| N (%) | 49 (6.8%) | 16 (2.2%) | 34 (4.7%) | 23 (3.2%) |

| AOR (95% CI) | 0.53 (0.28 – 0.99) | 0.85 (0.31 – 2.33) | 0.56 (0.27 – 1.17) | 0.55 (0.23 – 1.32) |

| Absolute Risk Difference** | 0.083 | 0.004 | 0.026 | 0.018 |

| Number Needed to Treat (95% CI)*** |

12 (5 – 642) |

--- |

--- |

--- |

| PP: | ||||

| N (%) | 72 (8.7%) | 36 (4.4%) | 62 (7.5%) | 27 (3.3%) |

| AOR (95% CI) | 0.56 (0.34 – 0.93) | 0.39 (0.18 – 0.82) | 0.47 (0.27 – 0.82) | 0.99 (0.46 – 2.16) |

| Absolute Risk Difference** | 0.045 | 0.037 | 0.050 | 0.001 |

| Number Needed to Treat (95% CI)*** | 22 (14 – 146) | 27 (20 – 96) | 20 (14 – 61) | --- |

Notes: IPV: Intimate Partner Violence; BL: Baseline; FU1: First Follow-up (22-26 weeks gestation); FU2: Second Follow-up (34-38 weeks gestation); PP: Postpartum; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval.

Adjusted for alcohol use during pregnancy and depression at baseline.

Absolute difference between intervention and usual care groups.

Number needed to treat is calculated for significant adjusted odds ratios and significant risk differences.

For women experiencing IPV victimization throughout pregnancy and postpartum, Table 4 presents a comparison of intervention and usual care women with respect to various adverse pregnancy outcomes. The results indicate that rates of low birthweight (<2,500 grams) (LBW) were not different in the two groups (intervention=12.8% versus usual care=18.5%, p=0.204), while very low birthweight (<1,500 grams) (VLBW) rates were lower among intervention women (intervention=0.8% versus usual care=4.6%, p=0.052). In addition, rates of preterm births (37 weeks gestation) (PTB) were not statistically different in the two groups (13.0% versus 19.7%, p=0.135). However, the two groups of women were significantly different with respect to very PTB (<33 weeks gestation) (VPTB) (1.5% versus 6.6%, p=0.030). Also, for the mean gestational age at delivery, the two groups were significantly different (38.2 weeks versus 36.9 weeks, p=0.016).

Table 4.

Pregnancy Outcomes among Women Experiencing Intimate Partner Violence throughout Pregnancy and Postpartum by Care Group

| Characteristic | Intervention (n=150) | Usual Care (n=156) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LBW | 17 (12.8%) | 24 (18.5%) | 0.204 |

| VLBW | 1 (0.8%) | 6 (4.6%) | 0.052 |

| Birth Weight (grams): Mean ± SD | 3139 ± 593 | 3098 ± 717 | 0.618 |

| PTB | 18 (13.0%) | 27 (19.7%) | 0.135 |

| VPTB | 2 (1.5%) | 9 (6.6%) | 0.030 |

| Gestational Age at Delivery (weeks) : Mean ± SD | 38.2 ± 3.3 | 36.9 ± 5.9 | 0.016 |

Note: LBW: Low Birth Weight; VLBW: Very Low Birth Weight; PTB: Preterm Birth; VPTB: Very Preterm Birth; SD: Standard Deviation

DISCUSSION

This study evaluates efficacy of a psycho-behavioral intervention during prenatal and postpartum care on the reduction of IPV recurrence and improved pregnancy outcomes in African-American mothers reporting IPV victimization. We were able to recruit 336 women acknowledging IPV victimization within the past year during the baseline interview and who were willing to participate in the intervention. In addition, 91% of these women continued to participate in this randomized trial during pregnancy and/or postpartum. This finding emphasizes the relative ease of recruitment of high risk African-American women to IPV reduction programs in the PNC setting. The recruitment staff were trained to be culturally sensitive and the screening tool was both simple and administered confidentially. These women are also willing to maintain participation in a program that provided cognitive behavioral strategies relevant to psycho-behavioral problems they experienced during pregnancy.

The integrated intervention provided women with suggestions to deal with depression and tobacco exposure in addition to strategies aimed at reducing risk of IPV. Alternative explanations for our findings were considered. For other services for which we queried the women, there were no differences between women experiencing IPV and those not. We also considered whether women's previous reproductive history might explain why the intervention group had significantly better outcomes. None of the factors (previous preterm delivery, previous miscarriage, previous stillbirth, number of previous voluntary interruptions of pregnancy) that might predict poor reproductive outcomes were different between the two care groups. Finally we considered whether medical conditions that might influence pregnancy outcomes (preconception and gestational diabetes, chronic and gestational hypertension, or sexually transmitted infections) were significantly different between the two care groups. None of these medical conditions were significantly different between the two care groups.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists identifies the response to domestic violence against women as a priority and recommends screening within primary care settings.43 They also recommend the Patient Health Questionnaire as a screening instrument for IPV, depression and anxiety. This questionnaire recognizes the co-occurrence of these psychosocial risks as well as screening for substance exposure known to occur more frequently in victims of IPV.24-27, 31 The findings of our study confirm the importance of emphasizing a more global approach towards risk assessment and service provision to this population of high risk African-American mothers.

IPV has been associated with poor pregnancy outcomes in the literature.28, 30, 32-34, 44-47 Our study is the first we are aware of that found reductions in adverse pregnancy outcomes despite previous evidence for associations between IPV during pregnancy and LBW.28, 30, 32-34 The intervention model targeting multiple risk factors in African-American women suffering from IPV victimization shows promising results that could be translated toward reduction of infant mortality within that population. The current literature agrees that very preterm infants contribute more than 90% of the overall infant mortality statistic.48 The effect of the intervention impacted multiple pregnancy outcomes, especially the highest level of neonatal risk, VLBW and VPTB. The significant reduction of VLBW and VPTB in our intervention group may have important implications on reduction of disparities in poor pregnancy outcomes and infant mortality among African-Americans.

Whether or not our analyses were adjusted for alcohol use and depression, the intervention universally reduced minor IPV during pregnancy and postpartum. It is important to recognize that the classification of minor IPV on the Conflict Tactics Scale includes acts of assault such as slapping, grabbing, pushing and shoving as well as twisting of the arm or hair. While such actions may be considered minor on the CTS they are significant acts of aggression and violence. The intervention was unable to impact more severe acts described as using a knife or gun, choking, burning, scalding or kicking. The lack of effect on sexual IPV could be attributed to the reluctance or discomfort of the study participants to divulge or discuss these topics. The intervention team was instructed to show sensitivity to the level of comfort of the study participants in this domain. The intervention as designed and implemented only reduced the recurrence of minor and physical IPV, but could have reduced other associated risks.

The impact of IPV on pregnancy outcome is complicated by its co-occurrence with depression and alcohol use.47,49-51 The behavioral intervention for depression could have significantly contributed to our success. Among the women reporting IPV at baseline, 62 percent reported being depressed and 32 percent reported alcohol use during pregnancy. Addressing IPV and depression together may have helped women implement suggested strategies to assess risks, consider preventive options and develop a safety plan. We also detected a significant association between IPV and illicit drug use (16.7%) and active smoking (22%), both known to be risks for PTB and LBW.52,53 In reduced logistical models, alcohol use during pregnancy and depression measured at baseline continued to exert a significant influence on perpetuating IPV during pregnancy and postpartum. This describes a cycle where co-occurring risk factors are immutably entangled.

A limitation of the study was that it was not powered to test the efficacy of the intervention with respect to adverse pregnancy outcomes, but rather resolution of the psycho-behavioral risks. Women were only modestly invested in participating in the intervention. Despite the fact that we were able to deliver the minimum number of intervention sessions to 59% of participants with IPV, women randomized to the intervention were successful in risk reduction. These rates of participation may be a reflection of difficult life circumstances among poor urban women. These mothers encountered other behavioral challenges during pregnancy, such as alcohol and drug use, that were not addressed by the intervention. Had we addressed these, we might have been even more successful. The intervention effect(s) we found may apply only to high risk minority pregnant women. It would be important to test this intervention in other racial or sociodemographic groups to confirm generalizability. Larger studies testing the effectiveness of implementing such interventions in community based clinics providing PNC could have important health policy implications.

There is evidence that this intervention for pregnant African-American women reduced IPV victimization during pregnancy and improved pregnancy outcome. If generalizable, our results should encourage health care providers and third party payers to go beyond screening for psycho-social and behavioral risks to providing services during PNC to address such risks. The potential cost savings associated with reduction of births within the highest risk category may be substantial.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grants no. 3U18HD030445; 3U18HD030447; 5U18HD31206; 3U18HD031919; 5U18HD036104, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities

Footnotes

RTI International is a trade name of Research Triangle Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gunter J. Intimate partner violence. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34(3):367–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Violence against women. WHO Consultation, Geneva 5-7 February 1996. Geneva World Health Organization. 1996 document FRH/WHD/96.27. [February 17, 2009]; Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1996/FRH_WHD_96.27.pdf.

- 3.Saltzman LE, Fanslow JL, McMahon PM, et al. Intimate partner violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements version 1.0. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, Kub J, Schollenberger J, O'Campo P, Gielen AC, Wynne C. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1157–1163. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullerman R, Lenaghan PA, Pakieser RA. Battered women: injury locations and types. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:486–492. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC National Center for Prevention and Control [March 9, 2009];Intimate partner violence: Fact sheet, 2006. Available at www.cdc.gov/ncipc/dup/ipv_factsheet.pdf.

- 7.Dietz PM, Gamararian JA, Goodwin MM, Bruce FC, Johnson CH, Rochat RW. Delayed entry into prenatal care: effect of physical violence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(2):221–224. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00252-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark C, et al. Neighborhood poverty as a predictor of intimate partner violence among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the United States: a multilevel analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodwin MM, Gazmararian JA, Johnson CH, Gilbert BC, Saltzman LE. Pregnancy intendedness and physical abuse around the time of pregnancy: findings from the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 1996-1997. PRAMS Working Group. Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4(2):85–92. doi: 10.1023/a:1009566103493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caetano R, Field CA, Ramisetty-Mikler S, McGrath C. The 5-year course of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. J Interpers Violence. 2005;20(9):1039–1057. doi: 10.1177/0886260505277783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiemann CM, Agurcia CA, Berenson AB, Volk RJ, Rickert VI. Pregnant adolescents: experiences and behaviors associated with physical assault by an intimate partner. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4(2):93–101. doi: 10.1023/a:1009518220331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renker PR. Physical abuse, social support, self-care, and pregnancy outcomes of older adolescents. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1999;28(4):377–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1999.tb02006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence in eighteen U.S. states/territories, 2005. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhandari S, Levitch AH, Ellis KK, Ball K, Everett K, Geden E, Bullock L. Comparative analyses of stressors experienced by rural low-income pregnant women experiencing intimate partner violence and those who are not. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37(4):492–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavao J, Alvarez J, Baumrind N, Induni M, Kimerling R. Intimate partner violence and housing instability. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(2):143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stueve A, O'Donnell L. Urban young women's experiences of discrimination and community violence and intimate partner violence. J Urban Health. 2008;85(3):386–401. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9265-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raghavan C, Rajah V, Gentile K, Collado L, Kavanagh AM. Community Violence, Social Support Networks, Ethnic Group Differences, and Male Perpetration of Intimate Partner Violence. J Interpers Violence. 2009 Mar 3; doi: 10.1177/0886260509331489. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Field CA, Caetano R. Longitudinal model predicting partner violence among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(9):1451–1458. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000086066.70540.8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reviere SL, Farber EW, Twomey H, Okun A, Jackson E, Zanville H, Kaslow NJ. Intimate partner violence and suicidality in low-income African-American women: a multimethod assessment of coping factors. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(11):1113–1129. doi: 10.1177/1077801207307798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin SL, Macy RJ, Sullivan K, Magee ML. Pregnancy-associated violent deaths: the role of intimate partner violence. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8(2):135–148. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazen AL, Connelly CD, Soriano FI, Landsverk JA. Intimate partner violence and psychological functioning in Latina women. Health Care Women Int. 2008;29(3):282–299. doi: 10.1080/07399330701738358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez S, Johnson DM. PTSD compromises battered women's future safety. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(5):635–651. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, Kub J, Schollenberger J, O'Campo P, et al. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1157–1163. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amaro H, Fried L, Cabral H, Zuckerman B. Violence during pregnancy and substance use. American Journal of Public Health. 1990;80:575–579. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.5.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin SL, English KT, Clark KA, Cilenti D, Kupper LL. Violence and substance abuse among North Carolina pregnant women. American Journal Public Health. 1996;86:991–998. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.7.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin SL, Beaumont JL, Kupper LL. Substance use before and during pregnancy: links to intimate partner violence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29(3):599–617. doi: 10.1081/ada-120023461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berenson A, Stiglich N, Wilkinson G, Anderson G. Drug abuse and other risk factors for physical abuse in pregnancy among White non-Hispanic, Black, and Hispanic women. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1991;164:491–499. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)91428-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berenson AB, Wiemann CM, Wilkinson GS, Jones WA, Anderson GD. Perinatal morbidity associated with violence experienced by pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170(6):1760–1766. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70352-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell J, Poland M, Waller J, Ager J. Correlates of battering during pregnancy. Research in Nursing & Health. 1992;15:219–226. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K. Abuse during pregnancy: Associations with maternal health and infant birthweight. Nursing Research. 1996a;45:3742. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K. Physical abuse, smoking, and substance use during pregnancy: Prevalence, interrelationships and effects on birthweight. Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecological and Neonatal Nursing. 1996b;25:313–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb02577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moraes CL, Amorim AR, Reichenheim ME. Gestational weight gain differentials in the presence of intimate partner violence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(3):254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yost NP, Bloom SL, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. A prospective observational study of domestic violence during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(1):61–5. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000164468.06070.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janssen PA, Holt VL, Sugg NK, Emanuel I, Critchlow CM, Henderson AD. Intimate partner violence and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(5):1341–7. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.EI-Khorazaty MN, Johnson AA, Kiely M, El-Mohandes AAE, Subramanian S, Laryea HA, Murray KB, Thornberry JS, Joseph JG. Recruitment and retention of low-income minority women in a behavioral intervention to reduce smoking, depression, and intimate partner violence during pregnancy. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:233. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katz KS, Blake SM, Milligan RA, Sharps PW, White DB, Rodan MF, Rossi MA, Murray KB. The design, implementation and acceptability of an integrated intervention to address multiple behavioral and psychosocial risk factors among pregnant African American women. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2008;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parker B, McFarlane J, Soeken K, Silva C, Reel S. Testing an intervention to prevent further abuse to pregnant women. Res Nurs Health. 1999;22(1):59–66. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199902)22:1<59::aid-nur7>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dutton MA. Empowering and healing battered women. Springer; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 40.DiClemente CC, Prochaska J, Fairhurst SK, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, Rossi JS. The process of smoking cessation: an analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(2):295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miranda J, Munoz R. Intervention for minor depression in primary care patients. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1994;56(2):136–141. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K, Bullock L. Assessing for abuse during pregnancy. JAMA. 1992;267(23):3176–3178. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.23.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Durant T, Colley Gilbert B, Saltzman LE, Johnson CH. Opportunities for intervention: discussing physical abuse during prenatal care visits. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;19(4):238–244. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neggers Y, Goldenberg R, Cliver S, Hauth J. Effects of domestic violence on preterm birth and low birth weight. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83(5):455–60. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fried LE, Cabral H, Amaro H, Aschengrau A. Lifetime and during pregnancy experience of violence and the risk of low birth weight and preterm birth. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008;53(6):522–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodrigues T, Rocha L, Barros H. Physical abuse during pregnancy and preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(2):171.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown SJ, McDonald EA, Krastev AH. Fear of an intimate partner and women's health in early pregnancy: findings from the Maternal Health Study. Birth. 2008;35(4):293–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Callaghan WM, MacDorman MF, Rasmussen SA, Qin C, Lackritz EM. The contribution of preterm birth to infant mortality rates in the United States. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1566–1573. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bailey BA, Daugherty RA. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: incidence and associated health behaviors in a rural population. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(5):495–503. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fife RS, Ebersole C, Bigatti S, Lane KA, Brunner Huber LR. Assessment of the relationship of demographic and social factors with intimate partner violence among Latinas in Indianapolis. J Women's Health. 2008;17(5):769–775. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paranjape A, Heron S, Thompson M, Bethea K, Wallace T, Kaslow N. Are alcohol problems linked with an increase in depressive symptoms in abused, inner-city African American women? Womens Health Issues. 2007;17(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cnattingius S. The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(Suppl 2):S125–140. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Windham GC, Hopkins B, Fenster L, Swan SH. Prenatal active or passive tobacco smoke exposure and the risk of preterm delivery or low birth weight. Epidemiology. 2000;11(4):427–433. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200007000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]