Summary

Riboswitches are highly structured elements residing in the 5' untranslated region of messenger RNAs that specifically bind cellular metabolites to alter gene expression. While there are many structures of ligand bound riboswitches that reveal details of bimolecular recognition, their unliganded structures remain poorly characterized. Characterizing the molecular details of the unliganded state is crucial for understanding the riboswitch's mechanism of action because it is this state that actively interrogates the cellular environment and helps direct the regulatory outcome. To develop a detailed description of the ligand free form of an S-adenosylmethionine binding riboswitch at the local and global levels, we have employed a series of biochemical, biophysical, and computational methods. Our data reveals that the ligand binding domain adopts an ensemble of states that minimizes the energy barrier between the free and bound states to establish an efficient decision making brachpoint in the regulatory process.

Introduction

Riboswitches are cis-acting mRNA regulatory elements that modulate gene expression through their ability to bind small molecule metabolites with high specificity (Montange and Batey, 2008; Roth and Breaker, 2009). Ligand binding to a receptor, called the aptamer domain, redirects the folding outcome of the 5'-untranslated region of the mRNA, thereby determining the expression fate of the mRNA (Garst and Batey, 2009). During transcription, the branchpoint of two parallel folding pathways occurs at a point when a sufficient amount of the mRNA has been synthesized and folded such that it can actively interrogate the cellular environment for ligand (Fig. 1a; sensing phase). To be an effective regulator of gene expression, the unliganded state of the riboswitch must maintain ligand-binding competence without negating the ability to follow a default folding pathway in the absence of ligand. As regulatory decisions by the secondary structural switch are being made, the mRNA likely becomes locked into a single path that can no longer exchange with the other on a timescale relevant to transcriptional regulation (Fig. 1a; regulatory phase). Despite significant progress in understanding how riboswitches recognize their cognate ligand (Montange and Batey, 2008; Roth and Breaker, 2009), their folding pathways and the nature of the unbound state during the sensing phase are not well defined.

Figure 1. Regulation and structure of the SAM-I riboswitch.

(a) Transcription of a nascent riboswitch RNA. The first phase is the synthesis and magnesium-induced folding of the aptamer domain (folding phase). During the second phase, the aptamer interrogates the cellular environment for the presence of SAM (sensing phase). The final phase (regulatory phase) occurs after sufficient downstream sequence has been synthesized to allow for formation of secondary structural elements that direct the expression machinery. (b) Structure of the SAM-I aptamer domain used in this study, highlighting key tertiary interactions including the 24/64/85 base triple, pseudoknot interaction (PK), and the kink-turn (KT). (c) Crystal structure of the SAM-I aptamer in complex with SAM, colored according to the secondary structure (PDB ID 2GIS).

Previous studies have presented an inconsistent picture of the apo-form of riboswitches. One perspective arises from the crystal structures of the Thermotoga maritima asd lysine riboswitch in both the apo and bound forms that reveal almost identical structures (Garst et al., 2008; Serganov et al., 2008). Since the binding pocket for lysine is completely solvent inaccessible, this cannot represent the binding competent form, as suggested by SAXS and chemical probing data (Garst et al., 2008; Sudarsan et al., 2003). Conversely, NMR studies of the free and bound form of the Bacillus subtilis queC preQ1 riboswitch indicated that the receptor is largely unstructured in the absence of ligand binding (Kang et al., 2009). It is not clear how the ligand can efficiently recognize such a disorganized binding pocket RNA in a short temporal window during transcription. Finally, the apo-state of the guanine riboswitch appears to be somewhere in the middle of these two extremes. Chemical probing analysis of this RNA demonstrated that part of the binding pocket is conformationally restricted prior to ligand binding while other regions remain flexible allowing the RNA to fold around guanine upon an initial docking event to yield the structure observed by X-ray crystallography (Gilbert et al., 2006; Stoddard et al., 2008). This view of a partially organized binding pocket in the guanine/adenine riboswitches is supported by NMR studies (Ottink et al., 2007) and molecular dynamics simulations (Priyakumar and Mackerell, 2009; Sharma et al., 2009; Villa et al., 2009). It is most likely that all of these RNAs adopt an ensemble of rapidly interconverting states in the absence of ligand with only a sub-population that are competent to bind ligand, as observed in HIV transactivation element (Zhang et al., 2007). However, the molecular details of the ensemble structures of unliganded riboswitches remain elusive.

To develop a molecular-level understanding of the ensemble of states that a riboswitch aptamer domain experiences during the sensing phase, we have analyzed a sequence based upon the Thermoanearobacter tengcongensis metF-H2 SAM-I riboswitch (Montange and Batey, 2006). This aptamer is found in varying regulatory contexts including transcriptional and translational control (Barrick and Breaker, 2007) and as a trans-acting non-coding RNA that regulates via an antisense mechanism (Loh et al., 2009). Because of the “mix-and-match” nature of riboswitch aptamer and expression platforms (Stoddard and Batey, 2006), analysis of the aptamer domain outside the context of its host RNA yields insights into the general behavior of ligand recognition. The aptamer domain exerts control over surrounding sequence elements rather than the converse. Thus, the reductionist approach required for this study yields biologically relevant insights into the regulatory activity of riboswitches.

The aptamer domain of the SAM-I riboswitch contains a conserved core comprised of a secondary structure defined by four helical regions (P1–P4) centered around a four-way junction with three joining regions (J1/2, J3/4, and J4/1) (Fig. 1b) (Epshtein et al., 2003; Grundy and Henkin, 1998; Winkler et al., 2003). The helices form two coaxial stacks (P1/P4 and P2/P3) that are organized through a set of tertiary interactions involving a pseudoknot (PK) between L2 and J3/4, a base triple tying together L2, J3/4 and J4/1, and several long-range interactions involving base triples between J1/2 and J3/4 and paired regions (Montange and Batey, 2006) (Fig 1c). S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) recognition is achieved through extensive hydrogen bonding interactions within a pocket created by the minor groove P3 and an electrostatic interaction between the positively charged sulfonium ion on SAM and the minor groove of P1 (Montange and Batey, 2006; Montange et al., 2010).

In this study, we have defined the features of both the folding of the aptamer and its structural flexibility in the absence of SAM. Chemical probing of the RNA revealed that magnesium facilitates formation of a subset of tertiary interactions in the RNA and that SAM is required to establish a protection pattern fully consistent with the crystal structure. These data suggest that the folded but unliganded RNA exists as an ensemble of states. In this ensemble, we identified conformations using small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) that are variable in the degree in which P1 and P3 “scissor” apart from each other allowing formation of multiple open orientations as well as a bound-like state with P1 and P3 in a closed orientation. Conformational heterogeneity is also observed at the local level within the SAM-binding pocket, as revealed by a crystallographic analysis of the free state along with replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) simulations. This study presents a comprehensive understanding of structural heterogeneity in a free state riboswitch aptamer domain and how magnesium and SAM binding reshape the folding landscape.

Results

Magnesium and SAM binding alter aptamer domain conformational sampling

To characterize magnesium- and SAM-dependent acquisition of tertiary architecture in the SAM-I riboswitch aptamer domain with nucleotide resolution, we utilized a chemical probing technique called selective 2’-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE) (Merino et al., 2005; Wilkinson et al., 2006). This approach employs N-methylisatoic anhydride (NMIA) as a probing reagent that selectively modifies 2'-hydroxyl groups within regions where the backbone is conformationally flexible (Gherghe et al., 2008). Conversely, nucleotides that are locked in helices or highly structured tertiary elements display low chemical reactivity.

SHAPE analysis was performed at a fixed temperature (20 °C) over a range of magnesium concentrations (0 to 10 mM) in the presence and absence of SAM (Fig. 2a). In the absence of SAM (Fig. 2a, lanes 1–8), the RNA undergoes multiple magnesium-induced structural transitions. The first folding transition is observed in the pseudoknot between 0.5 and 1 mM MgCl2, followed by an increased reactivity of positions 9 and 14 in J1/2 between 1 and 3 mM MgCl2. The increased modification in J1/2 is likely due to folding events that permit sampling of a bound-like conformation in which positions 9 and 14 are solvent exposed as observed in the crystal structure (Montange and Batey, 2006). Acquisition of other features characteristic of the folded, SAM-bound state are observed in the kink-turn, J3/4, and J4/1, which all display increasing levels of protection at higher magnesium concentrations but do not appear to become fully protected at 10 mM MgCl2.

Figure 2. Probing of SAM-I aptamer domain RNA folding.

(a) NMIA probing of magnesium-dependent changes in the SAM-I aptamer. Lanes 1–8 are in the absence of ligand, lanes 9–16 are in the presence of 1 mM SAM. (b) Ligand dependent changes in apparent melting temperatures mapped on the secondary structure of SAM-I. Colors represent the difference in Tm between bound and free RNAs; positions that do not display distinct two-state melting behavior are not included. (c) NAIM analysis using analogs of guanine (inosine, yellow) and adenine (2AP, red; DAP, cyan) identifies specific nucleotide positions as important for folding and/or binding.

Since chemical probing reports the bulk ensemble RNA folding behavior, the observed pattern of magnesium-dependent protections reflects a population sampling conformations associated with varying degrees of tertiary architecture formation. In the presence of SAM (Fig. 2a, lanes 9–16), almost the entire RNA becomes protected from modification over a narrow magnesium concentration range (0.5 – 1 mM MgCl2). Furthermore, in a manner distinct from modification patterns in the absence of ligand, a complete population shift from the free to bound state modification signature occurs in the pseudoknot and J1/2 as well as in the kink-turn, J3/4 and J4/1, suggesting these elements rarely sample structures lacking formation of tertiary architecture in the presence of SAM. This demonstrates that at physiological magnesium concentrations (0.5 – 1 mM), magnesium and SAM binding is coupled to fully stabilize the tertiary structure of the aptamer, as has been observed previously (Heppell and Lafontaine, 2008; McDaniel et al., 2005).

Temperature-dependent folding of the RNA was monitored in a similar fashion by probing at constant magnesium (6 mM MgCl2) over a broad temperature range (20–70 °C) (Fig. S1). The extent of modification, determined by band intensities for triplicate measurements, was quantified and the data was fit to a two state folding transition allowing the identification of apparent melting temperatures (Tm) for most nucleotide positions in the RNA (Fig. S2). Notably, the apparent Tm throughout the entire RNA increases in the presence of SAM, supporting the idea that the ligand significantly influences the stability of the global architecture of the RNA.

To reveal the influence of SAM on folding of the RNA, the difference between Tm values (ΔTm) in the presence and absence of SAM was determined (Fig. 2b) for all measurable positions. We observe that helical regions experience the least ligand-dependent changes in Tm while elements of tertiary architecture and nucleotides comprising the SAM binding pocket experience significant ligand dependent increases in their apparent Tm (Fig. 2b). The greatest changes are observed around a base triple (positions 24/64/85) that anchors J4/1 to the pseudoknot and J3/4, that displays a ~20 °C change in Tm. Other regions such as J1/2 display a more moderate SAM-dependent increase Tm (~10 °C), a result that supports molecular dynamics simulation predictions that J1/2 docking to P3 is sensitive to magnesium (Huang et al., 2009).

Nucleotide analog interference mapping (NAIM) is another probing technique that provides specific information about functional groups critical for both folding and binding (Ryder and Strobel, 1999; Strobel, 1999). For SAM-I, RNAs that properly fold and bind ligand are selected on the basis of an observed electrophoretic mobility shift in the presence of SAM (Fig. S3). RNAs rendered inactive by analog incorporation are not present in the selected population, which are analyzed by sequencing to identify sites at which a loss or gain of a single functional group in the RNA abrogates its interaction with SAM. Using three purine analogs (2-aminopurine and 2,6-diaminopurine as adenosine analogs and inosine as a guanosine analog), we observe interferences both inside and outside of the binding pocket (Fig. 2c). The majority of these interferences cluster within the 24-64-85 base triple, J3/4, and the kink-turn highlighting the importance of stabilizing interactions outside of the binding pocket that are required to bind ligand in a productive manner through maintaining proper folding.

Together, these experiments identify several features critical to folding of the SAM-I riboswitch. First, while magnesium can fully stabilize some elements of tertiary architecture, primarily the pseudoknot, other key features such as the base triple tying L2, J3/4, and J4/1 together are only marginally stable in the absence of SAM. The detailed NMIA reactivity patterns suggest that in the absence of ligand, the RNA exists as an ensemble of conformations ranging from minimal tertiary structure to the bound-like state. Increasing the concentration of magnesium favors the formation of structures that are increasingly reminiscent of the SAM-bound structure. Second, it is clear that addition of ligand globally stabilizes the architecture of the RNA. While the above experiments provide a wealth of information concerning the effects of ligand and magnesium binding on RNA folding, they yield limited information about the overall architecture of the RNA, and in particular, the interhelical organization. To provide a more complete model of aptamer domain RNA folding in the absence of ligand we have employed a small angle X-ray scattering analysis (SAXS).

Conformational heterogeneity of P1 and P3 in the absence of SAM identified by SAXS

SAXS is a technique in which the scattering of X-rays is highly sensitive to the structure of the macromolecule in solution (Lipfert and Doniach, 2007; Putnam et al., 2007). Since the free state RNA samples multiple conformations in solution, we can utilize computational approaches to identify a unique set of conformational states that best describes the observed X-ray scattering profile (Putnam et al., 2007). SAXS can therefore yield an unbiased structural perspective of globally distinct conformations of the RNA in the unliganded state. SAXS data was collected on the SAM-I aptamer domain in the presence and absence of 7.6 mM magnesium and/or 100 μM S-adenosylmethionine. To ensure the RNA sample was purely monomeric, each sample was passed through a gel filtration column immediately prior to an X-ray scattering analysis.

The experimental SAXS data were transformed into Kratky plots to evaluate the degree of macromolecular compaction (Doniach, 2001). For all data sets, we did not observe any radiation induced aggregation during data collection as judged by the unbiased distribution of points in the Guinier region (Fig. S4). In the absence of magnesium or SAM, the RNA displays a significant enrichment in the higher scattering angles, characteristic of an unfolded polymer in solution (Fig. 3a; grey) (Doniach, 2001). This lack of compaction could not be overcome with the addition of ligand (Fig. 3a; green), consistent with chemical probing data. However, in the presence of magnesium alone, there is a significant change in the scattering profile resulting in a comparable decrease in the radius of gyration (Fig. S4) and transition of the scattering profile into a more bell-shaped curve indicative of a folding event that shifts the RNA population towards a compacted state (Doniach, 2001). Addition of SAM and magnesium (Fig 3a; blue) further alters the profile compared to magnesium alone, indicating that although magnesium induces a large-scale global compaction in the aptamer, ligand binding also induces structural rearrangements consistent with the above chemical probing analysis.

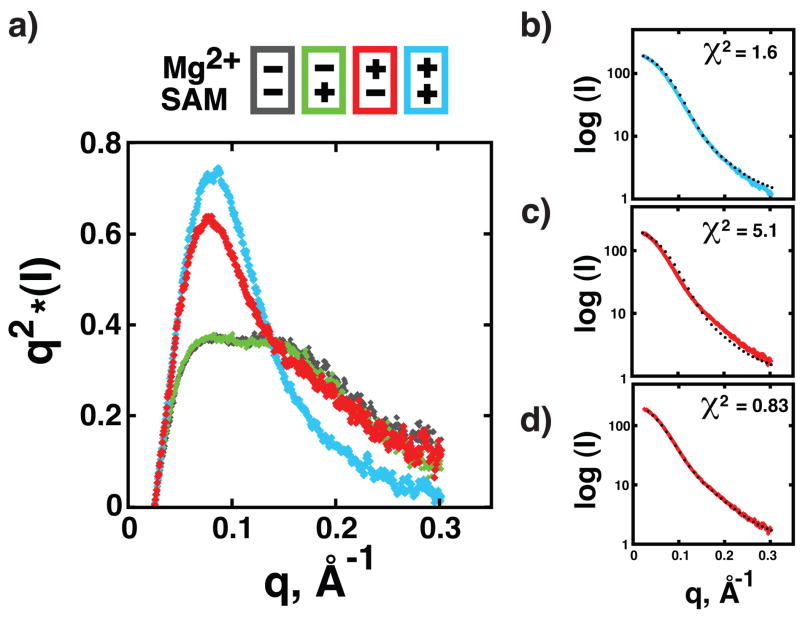

Figure 3. SAXS analysis of SAM-I solution structure.

(a) Kratky plot representation of scattering data in the presence or absence of ligand and/or magnesium. (b) Raw scattering data of SAM-I in the presence of ligand and magnesium (blue) with the theoretical scattering curve generated from the bound state aptamer domain crystal structure superimposed (2GIS). The intensity units for panels b, c, and d are on a relative scale. (c) Raw scattering data of the free state RNA in the presence of magnesium overlayed with the theoretical curve used in (b). (d) Scattering data of the free state RNA in the presence of magnesium overlayed with a theoretical scattering curve calculated from a set of structures representing frequently sampled conformations identified by an ensemble optimization algorithm (Figure 4).

The observed scattering profile of the RNA in the presence of magnesium and SAM is nearly identical to a theoretical scattering curve generated using the X-ray crystal structure of the bound SAM-I RNA (PDB ID 2GIS) (χ2 = 1.6) (Fig. 3b). However, the scattering profile in the presence of magnesium alone has a poor correlation (χ2 = 5.1) to the theoretical scattering curve calculated from the crystal structure (Fig. 3c). These data clearly show that the RNA collapses into a compacted state that is different from the bound X-ray structure in the presence of magnesium, but what is the molecular architecture of the states that are significantly populated in the ensemble of structures?

To model possible conformations of the aptamer domain that would be consistent with the scattering profile in the absence of SAM, torsion angle molecular dynamic simulations using the bound structure were performed. The X-ray crystal structure was divided into small discrete rigid bodies based on FIRST analysis that was further constrained by the RNA's secondary structure (Fulle and Gohlke, 2008). Regions of flexibility were chosen based on the NMIA chemical probing data to generate a set of trajectories that resulted in 9,000 different conformations of the RNA, and each conformation was used to calculate a theoretical scattering curve. The entire family of curves was used in an ensemble optimization algorithm against the experimental SAXS data to select the best set of conformations that modeled either the magnesium alone or magnesium/SAM SAXS data.

In the presence of magnesium and SAM, selected ensembles from the SAXS data are consistent with the bound X-ray crystal structure suggesting the solution structure of bound SAM-I is nearly identical to the X-ray crystal structure (Fig. S5). However, ensemble optimization of the magnesium only SAXS data yielded a solution structure defined by multiple alternative conformations. A theoretical scattering curve generated by this ensemble of structures is in excellent agreement with the experimental data (χ2 = 0.83) (Fig. 3d). Superposition of this ensemble of structures using a maximum likelihood method (Theobald and Wuttke, 2008) clearly shows that the conformation of a subdomain consisting of P4, the pseudoknot, and P2a/b is nearly identical to the bound structure (Fig. 4a). In contrast, the distance between P1 and P3 and their orientation relative to the P4-PK-P2a/b subdomain is variable and is accompanied by a significant twist relative to the bound state (Fig. 4b,c). These structures are similar to those generated by a molecular dynamics simulation study of SAM-I aptamer that employed a purely computational approach (Huang et al., 2009). Consistent with the chemical probing data, we observe bound-like states within the ensemble where P1 and P3 are positioned as they are in the crystal structure, indicating this state is accessible in the absence of ligand.

Figure 4. Ensemble of states that generates the best fit to experimental SAXS data.

(a) Overlay of the thirteen free state conformations using THESEUS (Theobald and Wuttke, 2008) reveals a large conformational heterogeneity in the orientation of the P1 (magenta) and P3 (green) helical regions relative to the P4 (blue)-PK-P2a/b subdomain (cyan). (b) Identical perspective as in (a), but helical regions are modeled as cylinders for clarity. The bound state is included in the superimposition and colored in grey both in a cylinder and ribbon representation. (c) Bottom view of structures represented in panel (b) illustrating the varying degree of openess between P1 and P3 as well as the significant twist relative to the P4-PK-P2a/b subdomain. Three distinct conformational extremes (1–3) and the crystallographically identified bound state (x) are labeled accordingly.

Local conformational heterogeneity in the binding pocket

We have identified aspects of global conformational changes occurring in the free aptamer domain in response to magnesium and ligand binding, however, local conformational changes in P3, suggested by chemical probing, cannot be resolved using SAXS. To investigate structural differences between the free and bound RNA, we crystallized the SAM-I RNA in the absence of SAM and solved its structure at 2.9 Å resolution (Table 1). The global free state structure is nearly identical to the bound state (maximum likelihood r.m.s.d. is 0.12 Å over all RNA atoms) (Fig. S6). This finding is consistent with the SAXS data indicating that the free RNA can sample a bound-like configuration.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data and refinement statistics.

| A94G, bound | A94G, free | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | P43212 | P43212 |

| Cell dimensions a=b, c (Å); α=β=γ (°) | 61.8, 157.6; 90 | 62.7, 159.2; 90 |

| Wavelengh (Å) | 1.5418 | 1.5418 |

| Resolution (Å) | 20 - 2.55 | 20 - 2.8 |

| Rmerge (%)a | 5.3 (34.3) | 8.2 (36.1) |

| I/σ(I)a | 16.4 (4.1) | 14.4 (4.4) |

| Completenessa | 99.3 (99.9) | 100 (99.8) |

| Redundancya | 5.0 (4.8) | 7.2 (5.5) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 20- 2.55 | 20- 2.9 |

| No. reflections | 18805 (1814) | 13401 (1237) |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 24.9/29.3 | 23.1/27.1 |

| No. atoms | ||

| RNA | 2030 | 2030 |

| Ligand/ion | 35 | 10 |

| Water | 47 | 94 |

| Mean B-factors (Å2) | ||

| RNA | 56.0 | 55.2 |

| Ligand/ion | 58.2 | 87.8 |

| Water | 35.9 | 45.2 |

| r.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (o) | 1.14 | 1.22 |

| Cross-validated Luzzati coordinate error | 0.49 | 0.47 |

| PDB accession code | 3IQR | 3IPQ |

Statistics for highest resolution shell are shown in parenthesis.

At the local level, the ligand free and bound forms of the RNA are also similar, except for a significant difference within the P3 region of the SAM binding pocket (Fig. 5a). In the bound state, an internal loop comprising two highly conserved nucleotides (A45 and U57) form a base triple with the adenosyl moiety of SAM while the third nucleotide (A46) is coplanar with the adjacent C47-G56 pair (Fig. 5a, bottom). In the absence of ligand, A46 replaces the adenosyl moiety of SAM to form a base triple with A46 and U57. In contrast to the adenosyl moiety of SAM, which interacts with U57 via its Hoogsteen face, A46 hydrogen bonds with U57 using its Watson-Crick face (Fig. 5a, top). It is important to note, however, that this structure cannot be the only one represented in solution, since A46 must be able to disengage from U57 in order for SAM to bind. Such dynamics are observed in the chemical probing reactivity pattern around these two nucleotides; in the absence of SAM both A45 and A46 show high degrees of NMIA reactivity while U57 appears to be static (Fig. 2a; compare lanes 8 and 16). Notably, when crystals of the unliganded RNA were soaked with 1 mM SAM, electron density within the binding pocket corresponding to SAM was clearly observed (Fig. 6). Therefore, the crystallographically observed free state is a fully active state capable of sensing SAM and implies decoupling of global P1/P3 scissoring from local opening and closing of the binding pocket in P3.

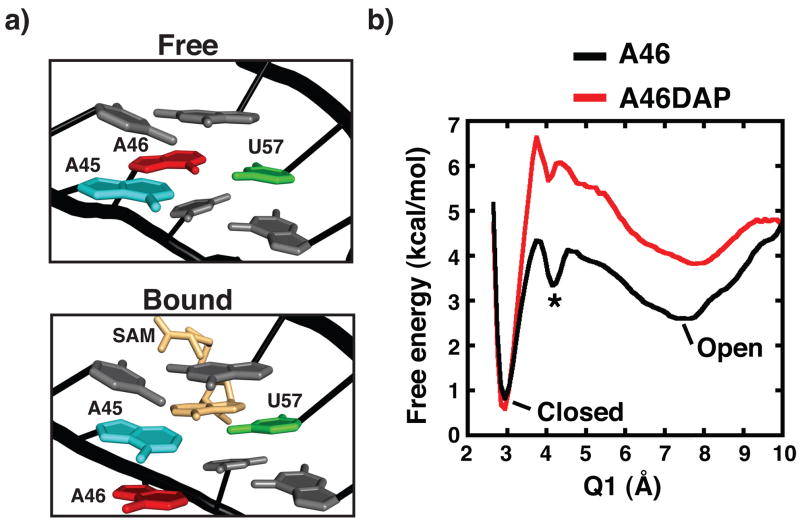

Figure 5. X-ray crystal structure and REMD analysis of the free aptamer.

(a) In the free RNA (top), a base triple between the three nucleotides that define the internal loop (A45, A46, and U57) is observed. In association with SAM (yellow), A46 is flipped out of the A45/U57 plane placing it in the minor groove adjacent to the C47-G56 pair (bottom). (b) Free energy landscape from REMD simulations of binding region using the free and bound crystal structures as initial states. The conformation of the internal loop is described by Q1, which characterizes the base pair hydrogen bond distance between A46 and U57. Two major energy minima are observed representing the closed (free) (~3 Å) and open (bound) (~7.5 Å) states as well as a subtle intermediate state (asterisk, ~4 Å).

Figure 6. Soak of apo-crystal with SAM.

(a) 2Fo-Fc map of the unliganded aptamer with the final model (PDB 3IQP) superimposed. (b) 2Fo-Fc map of the SAM-soaked apo-crystal in which the free state RNA was used as the model. Note extra density corresponding to the position of A46 (1) and SAM (2) in the bound structure. (c) 2Fo-Fc map of the same SAM soaked crystal in which the bound RNA (3IQR) was used as the model. Note that A46 is now well defined by density, and there still is unaccounted for density in the SAM binding pocket. (d) 2Fo-Fc map of the same crystal in which the bound RNA and SAM was used as the search model. The density around SAM is well defined indicating the presence of ligand.

The observed positioning of A46 in the free state may be a consequence of this conformation being the most stable among all accessible conformations. Chemical probing patterns for A45 and A46 suggests each residue adopts a reactive state in the absence of ligand implying that the unconstrained reactive state is energetically accessible. In an NMR study of a very similar internal loop motif, the nucleotide equivalent to A45 was observed to be unpaired but stacked within the helix while the equivalents of A46 and U57 form a Watson-Crick pair underscoring the potential for this internal loop to adopt a multiple conformations (Popenda et al., 2008). To provide further insights into potentially accessible conformations of A45 and A46 that can be sampled in the free state, we performed replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) simulations (Garcia and Sanbonmatsu, 2001).

REMD is an enhanced-sampling molecular dynamics technique that allows characterization of the equilibrium thermodynamics of a system(Mitsutake et al., 2001). This method has been previously applied to understanding RNA folding (Garcia and Paschek, 2008) and motions in the ribosomal RNA (Sanbonmatsu, 2006; Vaiana and Sanbonmatsu, 2009). Simulations were performed for 1.7 microseconds in explicit solvent on the region surrounding the P3 helix, including the SAM-binding site and portions of P1, P3, J1/2, J3/4 and J4/1, totaling 50 nucleotides (Movie S1). To characterize the free energy landscape, the parameter Q1 is used to describe the pairing interaction between A46 and U57 using the distance between ring nitrogen atoms as a measure of pairing (~3 Å) or lack of pairing (~7.5 Å). The free energy (the potential of mean force) determined by ΔG = - kT(log P(Q)) is then plotted as a function of Q1 (Fig. 5b; black). A second parameter, Q2 is also considered (Fig. S7) that reflects stacking between A45 and A46.

The energy landscape displays three conformational basins where the closed A46 conformation (C-A46) observed in the free state crystal structure and the open conformation (O-A46) observed in the bound state are observed as local energy minima. These minima are separated by a sufficiently low energy barrier such that in the absence of SAM these are the dominant conformers. A third subtle intermediate state was also identified that occupies a shallow energy well between the closed and open energy basins (Fig. 5b; asterisk). We note that transitions between basins occur often during the simulations, however, the closed A46 state is more stable than the open state by approximately 1–2 kcal/mol with an activation energy barrier of ~2–3 kcal/mol. This suggests that the closed and open A46 states are rapidly sampled by the SAM binding pocket.

As a further measure of the importance of position 46, we refer to the NAIM analysis (Fig. 2c). Incorporation of either 2-aminopurine (2AP) or 2,6-diaminopurine (DAP) at positions 45 and 46 is detrimental to formation of the ligand-induced electrophoretic gel shift. In each case, addition of a 2-amino group is deleterious to SAM binding. Interference of DAP and 2AP at the 100% conserved position 45 is likely the result of a steric clash with SAM, thereby directly preventing binding. However, the effect at position 46 is more difficult to explain, especially in light of the fact that guanosine is tolerated in 12% of the ~1200 known sequences (pyrimidine residues are never observed at this position) (Griffiths-Jones et al., 2003).

Based upon these data, a second REMD simulation (Movie S2) was performed in which A46 was replaced with (DAP) (Fig. 5b; red). One hypothesis is that the 2-amino group of DAP might stabilize the closed A46 state by allowing an additional hydrogen bond with U57. Upon REMD characterization of the closed A46 to open A46 transition, we observe that the DAP is more stable than the wild type sequence ( G ~1 kcal/mol) with a difference in activation barriers for collapsed to extended transition of ~1–2 kcal/mol (when considering both Q1 and Q2) (Fig. S7). Together, the above experiments further highlight the importance of inherent conformational sampling in the free state RNA and how subtle sequence alterations can reshape the folding landscape.

Discussion

The coupling of RNA folding and ligand binding is central to regulating gene expression by riboswitches. A critical folding branchpoint is established immediately after the aptamer domain is transcribed since this is the domain that actively interrogates cellular metabolite concentrations. To act as an effective transcriptional regulator, the aptamer domain must rapidly fold while avoiding misfolding or non-productive kinetic traps to allow specific, high-affinity ligand binding. The free state must also be capable of directing the mRNA down one of two folding pathways depending upon whether it binds the appropriate ligand (Fig. 1a). This latter requirement implies that the aptamer domain adopts a metastable folding landscape that allows access to multiple folding states rather than a single free state, a critical feature that confers activity in RNAs and proteins by allowing reversible sampling of states that are of comparable stabilities (Boehr et al., 2009; Henzler-Wildman and Kern, 2007; Munro et al., 2009).

The free state aptamer domain is characterized by an ensemble of states that experience global and local conformational sampling rather than adopting a single, highly populated state. In the absence of magnesium and ligand, only elements of secondary structure are established resulting in a conformationally unrestricted ensemble in the folding phase that is not competent to bind ligand (Fig. 7). Addition of magnesium induces formation of the pseudoknot interaction, establishing a conformationally restricted ensemble that is competent to bind ligand thus establishing the sensing phase. Although this ensemble is characterized by an established P4-PK-P2a/b subdomain, the P1 and P3 helical regions sample a series of states via a “scissoring” motion that varies in the degree of displacement of one helix from the other (Fig. 4). This motion allows the aptamer access to a state that is structurally similar to the SAM-bound structure in the absence of ligand binding suggesting the energetic barriers between states in the sensing phase are easily traversed. The bound-like state is competent to bind ligand and the propensity to access this state is increased under elevated magnesium conditions, however, ligand binding is required to completely shift a population of RNAs to a homogeneous, fully-structured state. From an induced-fit binding model perspective (Leulliot and Varani, 2001; Williamson, 2000), ligand captures a near-native state (conformational capture) followed by limited conformational changes to adopt the fully “native” state. This view is consistent with previous observations of the purine riboswitch (Ottink et al., 2007; Stoddard et al., 2008).

Figure 7. Model of magnesium and ligand dependent folding in a transcriptionally controlled SAM-I riboswitch.

Magnesium binding initiates a collapse from a form with only established secondary structure (far left) to a conformationally restricted ensemble of structures characterized by formation of the P4-PK-P2a/b sub-domain. During the sensing phase, the aptamer rapidly samples conformations on both the global (scissoring of P1/P3) occurs and local (SAM binding pocket) levels (yellow box). Productive interactions with SAM result in the RNA following a folding pathway that results in formation of a terminator stem that terminates transcription (top). In the absence of ligand binding, a folding pathway is followed where the 3’ side of P1 is free to form alternative pairing interactions thus establishing the antiterminator stem and allows transcription to proceed (bottom).

Concurrent with global conformational changes are alterations in local pairing interactions within the critical internal loop in P3, which comprises a crucial part of the SAM binding pocket. The internal loop that binds the adenosyl moiety of SAM experiences at least two distinct equilibrium conformations, dominated by the closed and open A46 states (Fig. 7) that likely prevent the binding pocket from permanently collapsing into a state that is incompetent to bind ligand. Structural heterogeneity has been observed previously within similar internal loop compositions (Popenda et al., 2008), indicating that positioning two adenosine bases adjacent from an unpaired uridine may confer a unique pairing equilibrium that allows conformational sampling and may explain phylogenetic conservation trends. Notably, sampling of global and local structures are decoupled in the free state RNA, potentially allowing multiple folding pathways that lead to a unique folding outcome.

The maintenance of conformational heterogeneity within the free state SAM-I RNA is compatible with our current understanding of riboswitch-mediated gene regulation. In the free state of the aptamer domain, the RNA must be sufficiently structured to ensure productive interactions with ligand, yet also be partially unstructured to allow the default folding pathway to occur with high fidelity in the absence of ligand. Limiting conformational heterogeneity through the establishment of tertiary interactions selectively populates bound-like or binding competent states, which likely has a significant impact on the rate of binding, a critical parameter for riboswitch function (Wickiser et al., 2005). This process likely explains how the SAM-I riboswitch can be tuned to respond to differing concentrations of ligand in the same organism such that it can differentially control operons related to diverse aspects of sulfur metabolism (Tomsic et al., 2008). Small alterations in aptamer sequence could alter how the RNA populates the ensemble thereby changing its responsiveness. Weakening tertiary interactions in the P4-PK-P2a/b subdomain would allow the riboswitch to respond at elevated SAM concentrations relative to other SAM-I riboswitches in the same organism.

Most other classes of riboswitches are very likely to employ conformational sampling of an ensemble of states to control their switching behavior. While different classes of riboswitches appear to behave differently (Baird and Ferre-D'Amare, 2010), their idiosynchracies are a result of studying each RNA under varying magnesium, temperature, and ligand conditions. In addition, many of these studies have employed diverse phylogenetic variants that evolved to function under different cellular conditions. In the context of the cell and transcription, each individual riboswitch is likely tuned to populate an ensemble that includes near-native states in a fashion that meets the regulatory needs of a specific set of genes. Given the importance of dynamic conformational ensembles in a broad array of biological processes involving recognition (Boehr et al., 2009), it is not surprising that riboswitches use this as central means of coupling ligand binding to regulatory control.

Experimental Procedures

RNA preparation

DNA templates for transcription reactions were synthesized using complementary overlapping oligonucleotides (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc.) by PCR. RNA was transcribed and purified using methods previously described (Montange and Batey, 2006).

Selective 2' Hydroxyl Acylation analyzed by Primer Extension (SHAPE)

Reactions were performed in a modified format similar to that previously described (Stoddard et al., 2008). Modifications were initiated with 65 mM NMIA at a final concentration of 200 μM S-adenosylmethionine (Sigma-Aldrich) or with anhydrous DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) for negative control reactions. Primer extension reactions were allowed to proceed for 7 minutes. Data was analyzed as previously described (Stoddard et al., 2008) except for the PK interaction where the data was separated into to transitions and fit individually.

Nucleotide analog interference mapping (NAIM)

Phosphorothioate nucleotide analogs (Glen Research) were incorporated into RNA transcripts using previously described protocols (Ryder et al., 2000). Reactions containing RNA with and without 75 μM SAM were prepared in a buffer containing 250 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 500 mM KCl. Selection of SAM bound and free conformations was performed by separation on a native polyacrylamide gel (8% polyacrylamide, 0.5x TBE, 1.1 mM MgCl2) at 18 °C. For sequencing, the RNA was 3'-end labeled by ligating a 7 nucleotide DNA oligomer with an attached 3’-Alexafluor 488 (Molecular Probes).

Analysis was performed on an ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer capillary electrophoresis system (National Stable Isotope Resource facility, LANL). Samples were resuspended in 5 μL of 10 mM I2 in deionized formamide, heated to 90 °C for 2 min, diluted to 16 μL with formamide and loaded on the sequencer. Control samples for nonspecific cleavage were performed for each without iodine cleavage. Fluorescence electropherograms plotted with Origin 7, and after normalizing for variability in electrokinetic injection, sites of interference identified by the lack of a peak at the residue in the SAM-bound versus free samples.

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS)

Chromatographic separation of the RNA by gel filtration and analysis by multiangle light scattering (MALS) was performed as previously described (Rambo and Tainer, 2010). SAXS experiments were performed at Beamline 12.3.1 of the Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. 20 μL of purified RNA samples and corresponding flow-through buffers from the size-exclusion purifications were loaded into a 96-well plate. RNA samples were collected at a maximum concentration of 2–3 mg/mL and diluted serial in the plate. Sample loading and data collection is as described (Hura et al., 2009). All data collections were performed at room temperature. For each sample, three exposures were taken in the following order of 6, 60 and 6 seconds. The first and last 6 second exposures were directly overlaid to visually assess the potential for radiation damage.

The merging of the 6 and 60 second exposures and the overlays of the merged datasets were performed with PRIMUS (Konarev et al., 2003). Kratky plots were generated with Kaliedegraph. A graph theory analysis of the X-ray crystal structure 2GIS as implemented in the program FIRST was used to determine which regions of the RNA were most likely to be flexible or stiff. Information was compiled with the established secondary structure to determine a set of rigid body modeling constraints for torsion angle molecular dynamic simulations by CNS (Brunger et al., 1998). The simulations were performed with large time steps and no electrostatic potential in the force field calculation. Any variation in the initial constraints created a unique trajectory and final state of the RNA. The conformation of the RNA at each time step along a trajectory was written to a PDB file using VMD. All SAXS calculations from X-ray models were performed with CRYSOL using a solvent density of 0.334 electrons/A3 and solvent layer of 3Å (Svergun et al., 1995).

The fit between theoretical and experimental scattering curves was assessed using χ2 as defined by:

where c is a scaling factor, Iobs is the observed intensities, Imodel is the modeled SAXS intensities, and error(Iobs) is the measured error in Iobs. Assuming the experimental data is accurate and free of gross errors, an atomistic model with a χ2 of less than 2 is generally considered to be a model consistent with the experimental SAXS data. If a model produces a χ2 between 2 and 3, then the model is considered a poor model. More importantly, a meaningful value of χ2 is determined by noting that the putative model has a radius-of-gyration consistent with the data and that the fit of the model to the experimental data is evenly distributed typically confined to the lower angle scattering region (q < 0.2).

The final ensemble of conformers selected by EOM (Bernado et al., 2007) using the magnesium alone data consists of 13 members that cluster into two major groups: opened (11 members) and closed (2 members). Of the 11 opened members, they could be further reduced to 4 types of closely related structures, and therefore the small overfitting of the data, as indicated by a χ2 below 1, is due to the redundancy found in the selected members. EOM does not determine the optimal ensemble size and the value of χ2 can be artificially raised by arbitrarily pruning redundant members. However, to ensure the reproducibility of the results, we have chosen not to do so and present the full EOM-selected ensemble.

X-ray crystallography

Crystallographic models of the free state RNA were generated in a manner previously described (Montange and Batey, 2006; Montange et al., 2010). Ligand soaking experiments were performed with unbound crystals grown at 20 °C. Crystals were washed 3 three times with 10 μL mother liquor followed by three times with mother liquor supplemented with 0.5 mM S-adenosylmethionine. After washing, crystals were soaked in 6 μL SAM-supplemented mother liquor at 20 °C for 24 hours followed by cryoprotection as described below in solutions containing no SAM. All crystals were cryoprotected in mother liquor supplemented with 15% ethylene glycol with a 5 minute soak and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data was collected using a rotating copper anode X-ray source with an R-AXIS IV++ area detector (Rigaku). Data was indexed, scaled, and averaged using CrystalClear (Pflugrath, 1999) and the models refined in CNS (Brunger et al., 1998). Crystallographic data and refinement statistics are given in Table 1.

Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD) simulations

In replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD), a distribution of identical systems are simulated at different temperatures. When favorable, temperatures are exchanged between neighboring replica systems according to a Monte Carlo criterion, resulting in Boltzmann sampling. In a previous study of a similarly sized RNA system, convergence of the free energy landscape was obtained after approximately one microsecond of total sampling (Vaiana and Sanbonmatsu, 2009). We use a similar simulation strategy, including 48 replicas with temperatures 3.5 °C (276.5 K) < T < 174.5 °C (447.5 K), running on 384 processors of the LANL Coyote supercomputer, generating a total sampling of 1.7 microseconds. The simulations were performed in explicit solvent using particle mesh Ewald electrostatics and the Gromacs simulation code. The free energy is calculated using the potential of mean force ΔG =-kT log (P(Q)), where P(Q) is the probability of sampling state characterized by coordinate Q, P(Q) = N(Q)/Ntot, N(Q) is the number of states in configuration Q sampled during the simulation, and Ntot is total number of configurations sampled. The coordinate values Q1 and Q2 are defined as:

REMD simulations also provide the temperature dependence of ΔG(a,b,T), used here to separate enthalpic and entropic contributions to the free energy at T0 = 27 °C (300 K) for dissociation of S-adenosylmethionine from the binding site.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM083953 (to R.T.B.), the Los Alamos National Laboratories LDRD program and NIH ARRA RC1GM092031 (to K.Y.S). Support for data collection at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory SIBYLS beamline of the Advanced Light Source came from the DOE program Integrated Diffraction Analysis Technologies (IDAT) under Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231 with the U.S. Department of Energy. In this study, C.D.S. performed the chemical probing analysis, R.K.M. performed the crystallography, S.P.H. performed the NAIM experiments at LANL, S.P.H. and K.Y.S. performed REMD simulations, and R.P.R. performed the SAXS analysis. C.D.S. and R.T.B. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Footnotes

Accession numbers. Coordinates and structure factors for the SAM-I A94G variant RNA free and in complex with SAM have been deposited to the RCSB with accession numbers 3IQP and 3IQR, respectively.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baird NJ, Ferre-D'Amare AR. Idiosyncratically tuned switching behavior of riboswitch aptamer domains revealed by comparative small-angle X-ray scattering analysis. RNA. 2010;16:598–609. doi: 10.1261/rna.1852310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrick JE, Breaker RR. The distributions, mechanisms, and structures of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Genome Biology. 2007;8:R239. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernado P, Mylonas E, Petoukhov MV, Blackledge M, Svergun DI. Structural characterization of flexible proteins using small-angle X-ray scattering. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5656–5664. doi: 10.1021/ja069124n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehr DD, Nussinov R, Wright PE. The role of dynamic conformational ensembles in biomolecular recognition. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doniach S. Changes in biomolecular conformation seen by small angle X-ray scattering. Chem Rev. 2001;101:1763–1778. doi: 10.1021/cr990071k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epshtein V, Mironov AS, Nudler E. The riboswitch-mediated control of sulfur metabolism in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5052–5056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0531307100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulle S, Gohlke H. Analyzing the flexibility of RNA structures by constraint counting. Biophys J. 2008;94:4202–4219. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.113415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AE, Paschek D. Simulation of the pressure and temperature folding/unfolding equilibrium of a small RNA hairpin. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:815–817. doi: 10.1021/ja074191i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AE, Sanbonmatsu KY. Exploring the energy landscape of a beta hairpin in explicit solvent. Proteins. 2001;42:345–354. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20010215)42:3<345::aid-prot50>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garst AD, Batey RT. A switch in time: detailing the life of a riboswitch. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garst AD, Heroux A, Rambo RP, Batey RT. Crystal structure of the lysine riboswitch regulatory mRNA element. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22347–22351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800120200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherghe CM, Shajani Z, Wilkinson KA, Varani G, Weeks KM. Strong correlation between SHAPE chemistry and the generalized NMR order parameter (S2) in RNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12244–12245. doi: 10.1021/ja804541s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert SD, Stoddard CD, Wise SJ, Batey RT. Thermodynamic and kinetic characterization of ligand binding to the purine riboswitch aptamer domain. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:754–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S, Bateman A, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR. Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:439–441. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy FJ, Henkin TM. The S box regulon: a new global transcription termination control system for methionine and cysteine biosynthesis genes in gram-positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:737–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henzler-Wildman K, Kern D. Dynamic personalities of proteins. Nature. 2007;450:964–972. doi: 10.1038/nature06522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppell B, Lafontaine DA. Folding of the SAM aptamer is determined by the formation of a K-turn-dependent pseudoknot. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1490–1499. doi: 10.1021/bi701164y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Kim J, Jha S, Aboul-ela F. A mechanism for S-adenosyl methionine assisted formation of a riboswitch conformation: a small molecule with a strong arm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:6528–6539. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hura GL, Menon AL, Hammel M, Rambo RP, Poole FL, Tsutakawa SE, Jenney FE, Classen S, Frankel KA, Hopkins RC, et al. Robust proteomic-scale solution structure analyses determined efficiently by X-ray scattering (SAXS) Nat Methods. 2009;285:1414–1423. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M, Peterson R, Feigon J. Structural Insights into riboswitch control of the biosynthesis of queuosine, a modified nucleotide found in the anticodon of tRNA. Mol Cell. 2009;33:784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konarev PV, Volkov VV, Sokolova AV, Koch MHJ, Svergun DI. PRIMUS: a Windows PC-based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. J Appl Crystallogr. 2003;36:1277–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Leulliot N, Varani G. Current topics in RNA-protein recognition: Control of specificity and biological function through induced fit and conformational capture. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7947–7956. doi: 10.1021/bi010680y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipfert J, Doniach S. Small-angle X-ray scattering from RNA, proteins, and protein complexes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2007;36:307–327. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh E, Dussurget O, Gripenland J, Vaitkevicius K, Tiensuu T, Mandin P, Repoila F, Buchrieser C, Cossart P, Johansson J. A trans-Acting Riboswitch Controls Expression of the Virulence Regulator PrfA in Listeria monocytogenes. Cell. 2009;139:770–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel BA, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM. A tertiary structural element in S box leader RNAs is required for S-adenosylmethionine-directed transcription termination. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:1008–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino EJ, Wilkinson KA, Coughlan JL, Weeks KM. RNA structure analysis at single nucleotide resolution by selective 2'-hydroxyl acylation and primer extension (SHAPE) J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4223–4231. doi: 10.1021/ja043822v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsutake A, Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Generalized-ensemble algorithms for molecular simulations of biopolymers. Biopolymers. 2001;60:96–123. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:2<96::AID-BIP1007>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montange RK, Batey RT. Structure of the S-adenosylmethionine riboswitch regulatory mRNA element. Nature. 2006;441:1172–1175. doi: 10.1038/nature04819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montange RK, Batey RT. Riboswitches: emerging themes in RNA structure and function. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:117–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.130000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montange RK, Mondragon E, van Tyne D, Garst AD, Ceres P, Batey RT. Discrimination between Closely Related Cellular Metabolites by the SAM-I Riboswitch. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro JB, Sanbonmatsu KY, Spahn CM, Blanchard SC. Navigating the ribosome's metastable energy landscape. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottink OM, Rampersad SM, Tessari M, Zaman GJ, Heus HA, Wijmenga SS. Ligand-induced folding of the guanine-sensing riboswitch is controlled by a combined predetermined induced fit mechanism. RNA. 2007;13:2202–2212. doi: 10.1261/rna.635307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflugrath JW. The finer things in X-ray diffraction data collection. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:1718–1725. doi: 10.1107/s090744499900935x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popenda L, Adamiak RW, Gdaniec Z. Bulged adenosine influence on the RNA duplex conformation in solution. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5059–5067. doi: 10.1021/bi7024904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priyakumar UD, Mackerell AD., Jr Role of the Adenine Ligand on the Stabilization of the Secondary and Tertiary Interactions in the Adenine Riboswitch. J Mol Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam CD, Hammel M, Hura GL, Tainer JA. X-ray solution scattering (SAXS) combined with crystallography and computation: defining accurate macromolecular structures, conformations and assemblies in solution. Q Rev Biophys. 2007;40:191–285. doi: 10.1017/S0033583507004635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambo RP, Tainer JA. Improving small-angle X-ray scattering data for structural analyses of the RNA world. RNA. 2010;16:638–646. doi: 10.1261/rna.1946310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A, Breaker RR. The structural and functional diversity of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:305–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070507.135656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder SP, Ortoleva-Donnelly L, Kosek AB, Strobel SA. Chemical probing of RNA by nucleotide analog interference mapping. Methods Enzymol. 2000;317:92–109. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)17008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder SP, Strobel SA. Nucleotide analog interference mapping. Methods. 1999;18:38–50. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanbonmatsu KY. Energy landscape of the ribosomal decoding center. Biochimie. 2006;88:1053–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serganov A, Huang L, Patel DJ. Structural insights into amino acid binding and gene control by a lysine riboswitch. Nature. 2008;455:1263–1267. doi: 10.1038/nature07326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Bulusu G, Mitra A. MD simulations of ligand-bound and ligand-free aptamer: molecular level insights into the binding and switching mechanism of the add A-riboswitch. RNA. 2009;15:1673–1692. doi: 10.1261/rna.1675809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard CD, Batey RT. Mix-and-match riboswitches. ACS Chemical Biology. 2006;1:751–754. doi: 10.1021/cb600458w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard CD, Gilbert SD, Batey RT. Ligand-dependent folding of the three-way junction in the purine riboswitch. RNA. 2008;14:675–684. doi: 10.1261/rna.736908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel SA. A chemogenetic approach to RNA function/structure analysis. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:346–352. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)80046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarsan N, Wickiser JK, Nakamura S, Ebert MS, Breaker RR. An mRNA structure in bacteria that controls gene expression by binding lysine. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2688–2697. doi: 10.1101/gad.1140003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svergun D, Barberato C, Koch MHJ. CRYSOL - A program to evaluate x-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. J Appl Crystallogr. 1995;28:768–773. [Google Scholar]

- Svergun DI, Semenyuk AV, Feigin LA. Small-Angle-Scattering-Data Treatment by the Regularization Method. Acta Crystallogr A. 1988;44:244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Theobald DL, Wuttke DS. Accurate structural correlations from maximum likelihood superpositions. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e43. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0040043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomsic J, McDaniel BA, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM. Natural variability in S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-dependent riboswitches: S-box elements in bacillus subtilis exhibit differential sensitivity to SAM In vivo and in vitro. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:823–833. doi: 10.1128/JB.01034-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaiana AC, Sanbonmatsu KY. Stochastic gating and drug-ribosome interactions. J Mol Biol. 2009;386:648–661. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa A, Wohnert J, Stock G. Molecular dynamics simulation study of the binding of purine bases to the aptamer domain of the guanine sensing riboswitch. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4774–4786. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickiser JK, Winkler WC, Breaker RR, Crothers DM. The speed of RNA transcription and metabolite binding kinetics operate an FMN riboswitch. Mol Cell. 2005;18:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson KA, Merino EJ, Weeks KM. Selective 2'-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE): quantitative RNA structure analysis at single nucleotide resolution. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1610–1616. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson JR. Induced fit in RNA-protein recognition. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:834–837. doi: 10.1038/79575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler WC, Nahvi A, Sudarsan N, Barrick JE, Breaker RR. An mRNA structure that controls gene expression by binding S-adenosylmethionine. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:701–707. doi: 10.1038/nsb967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Stelzer AC, Fisher CK, Al-Hashimi HM. Visualizing spatially correlated dynamics that directs RNA conformational transitions. Nature. 2007;450:1263–1267. doi: 10.1038/nature06389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.