Abstract

Background

Some authors have suggested that a posterior fixation suture on the lateral rectus muscle is ineffective, due to the muscle's long arc of contact with the globe. We report a small case series of patients successfully treated using a lateral rectus posterior fixation suture.

Methods

The surgical database of one surgeon (JMH) was reviewed for all cases undergoing lateral rectus posterior fixation surgery for mechanical or paretic strabismus. In all cases, the lateral rectus muscle was disinserted from the sclera and a Mersilene posterior fixation suture was placed 17 mm to 19 mm back from the insertion. The lateral rectus muscle was simultaneously recessed in all cases using a novel approach to allow adjustment of the recession if needed, while maintaining the posterior fixation suture. Outcome was assessed at least one year following surgery.

Results

Three patients were identified. Adduction deficit of the affected eye was caused by previous sinus surgery in two cases and scleral buckle surgery in one case. The lateral rectus posterior fixation suture on the unaffected eye induced the planned matching −1 limitation of abduction, with resulting improvement in incomitance of the exotropia and reduced angle of exodeviation on prism cover testing.

Conclusions

In this case series, a lateral rectus posterior fixation suture was useful in addressing incomitant exodeviations. It is unknown whether this technique is superior to alternative surgical approaches.

Introduction

In strabismus surgery, posterior fixation sutures are used to reduce the action of a muscle in its field of gaze. Posterior fixation sutures are particularly useful in cases of incomitant strabismus to reduce the duction of the yoke muscle of the unaffected (contralateral) eye and balance it with the underacting muscle in the affected eye.1-5 Using a posterior fixation suture has also been called the “Faden” operation.5 The most common uses of posterior fixation sutures include the contralateral medial rectus muscle for abducens (sixth) nerve palsy, both medial rectus muscles for convergence excess esotropia, the superior rectus muscle for dissociated vertical deviation, and the contralateral inferior rectus muscle for a depression deficit.6

Although using a posterior fixation suture on the lateral rectus muscle has been reported previously,4,6-8 some authors have recently suggested that a posterior fixation suture on the lateral rectus muscle is ineffective, due to the muscle's long arc of contact with the globe.9 We report a series of cases where a posterior fixation suture was successfully used on the lateral rectus muscle, using a surgical technique that allows simultaneous postoperative adjustment of the amount of recession.

Patients and Methods

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained and all data were collected in a manner compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The surgical database of one surgeon (JMH) was searched from May 2002 to April 2009 to identify all patients who had undergone a posterior fixation suture on the lateral rectus muscle in the context of mechanical or paretic strabismus.

Surgical Procedure

The lateral rectus muscle was isolated through an inferotemporal fornix conjunctiva incision and was imbricated at the insertion with a single double armed 6-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl; Ethicon Inc, Somerville, NJ) suture on an S-29 spatulated needle (J555G, Ethicon Inc), as described by Del Monte and Archer,10 after cleaning the muscle of the Tenon's capsule and intermuscular septum. The muscle was then cut from the sclera and the globe retracted medially.

The lateral aspect of the globe was explored, lifting the belly of the lateral rectus muscle up, and the inferior oblique insertion was identified. A double armed 6-0 nonabsorbable Mersilene suture (Ethicon Inc) on a spatulated S-14 needle (1722G, Ethicon Inc) was then used for posterior fixation, taking a 3 mm partial scleral thickness bite 17–19 mm from the insertion as shown in Figure 1A, measured using a flexible plastic ruler which followed the curve of the globe. The Mersilene suture was then passed through the belly of the lateral rectus muscle, holding the muscle on stretch (Figure 1A), at a distance of one third from the superior and inferior edges of the muscle, at the desired distance from the cut end of the muscle, as described by Del Monte11 for a posterior fixation suture with fixed recession. (Figure 1A) For example, if a 7 mm recession was planned and the posterior fixation suture could be placed at 18 mm from the insertion, then the sutures were passed 11 mm from the end of the muscle (Figure 1A).

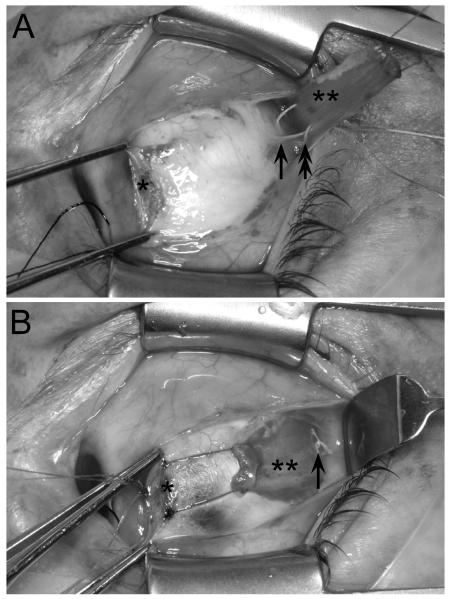

FIG 1.

Right eye, surgeon's view. A, Lateral rectus posterior fixation: 3 mm scleral bite (arrow) taken 18 mm from original insertion. Each arm of a double-armed Mersilene suture passed through the muscle belly, one third muscle width from superior and inferior edge (double arrow). B, The Mersilene suture is then tied over the middle third of the muscle (arrow). * indicates the original insertion of the lateral rectus muscle and ** indicates the lateral rectus muscle. This case shows a simultaneous recession of 7 mm on an adjustable suture.

If an adjustable recession was planned (2 cases), the muscle was reattached to the sclera at the insertion, taking partial thickness scleral bites in a cross-swords fashion.10 The sutures were then tied together, and a separate piece of 6-0 Vicryl suture was tied around the two sutures in the form of a sliding noose10 to initially set the desired recession. The posterior fixation Mersilene sutures were then slid anterior–posterior to create two slits in the muscle, parallel with the muscle fibers. These slits allow the muscle to slide forward or backward at the time of adjustment. We are unaware of a previous description of such slits to allow adjustment of the recession while maintaining a posterior fixation suture. The Mersilene suture was then tied but not so tight that the muscle would not slide if needed at adjustment of the recession (Figure 1B). The superior edge of the conjunctiva was then gently pulled back into the inferotemporal fornix. The adjustable suture ends were then secured loosely to the lateral canthal area using a Steri-Strip (3M Healthcare, St. Paul, MN). Assessment for adjustment was performed later the same day.

Results

Three patients were identified who underwent a lateral rectus posterior fixation suture on the unaffected eye for mechanical or paretic strabismus. Indications for the lateral rectus posterior fixation suture were medial rectus weakness of the affected eye from previous sinus surgery (n = 2) and adduction deficit of the affected eye from previous scleral buckle surgery (n = 1). All patients were adults, ages ranging from 51 to 71 years. Pre- and postoperative alignment was measured using prism and alternating cover tests (PACT), and duction deficits were assessed on a 0 to −5 scale.12 The area of diplopia was quantified by one or more of the following previously described methods: Goldmann test, cervical range of motion method, or Diplopia Questionnaire,13-16 scoring diplopia from 0 (no diplopia) to 100 (diplopia everywhere).

Case 1

A 68-year-old man underwent endoscopic sinus surgery and awoke with horizontal diplopia. He had single vision only in extreme right gaze and therefore adopted a large left face turn. On examination, 16 months after sinus surgery, he had a −3 limitation of right eye adduction (Figure 2A). In primary position at distance fixation, the exotropia measured 30Δ, with 52Δ exotropia, 7Δ right hypertropia in left gaze and 15Δ exotropia in right gaze. His diplopia scores were 100 (constant diplopia) on the Goldmann test, 92 using the cervical range of motion method, and 84 on the Diplopia Questionnaire.

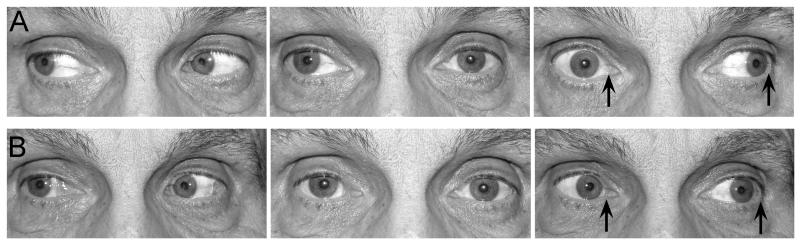

FIG 2.

A, Case 1, showing marked lag of adduction in the affected right eye preoperatively, caused by a weak right medial rectus muscle after endoscopic sinus surgery with imbalance of right eye adduction and left eye abduction (arrows), creating the incomitant exotropia. B, 6 weeks postoperatively, the lateral rectus recession with lateral rectus posterior fixation suture on the unaffected left eye has induced a matching −1 lag of abduction of the left eye, now balanced with the improved adduction of the right eye after medial rectus resection (arrows).

The patient underwent exploration of the right medial rectus muscle, which was found to be intact. Forced ductions to adduction were negative for restriction at the start of the procedure, indicating no leash phenomenon from a scarred medial rectus muscle and no tightness of the lateral rectus muscle. There were many adhesions medially from the muscle belly to the pulley structures and surrounding tissues. These adhesions were carefully cut to fully mobilize the muscle. Then the medial rectus muscle was resected 8 mm and hung back 1 mm on an adjustable suture using a sliding noose for an effective resection of 7 mm, to allow later adjustment of the resection if needed. Then the left lateral rectus muscle was recessed 7 mm on an adjustable suture, placing a posterior fixation suture 18 mm back from the original insertion, as described above.

At adjustment, the patient had a 2Δ esotropia at distance and a 4Δ exophoria at near. These measurements were considered close enough to the planned 4Δ to 6Δ esotropic alignment at distance, and so the sutures were tied off.

Six weeks postoperatively, the patient was orthotropic at distance and near fixation and in lateral gaze positions, with 2Δ esophoria in primary at distance fixation, 6Δ esophoria in right gaze, 4Δ exophoria in left gaze, and 2Δ exophoria at near fixation (Figure 2B). He had a normal head position and his ductions were now well matched into left gaze (Figure 2B), with mild residual −1 weakness of right eye adduction matched by t he −1 limitation of left eye abduction induced by the posterior fixation suture on the lateral rectus muscle.

Thirteen months postoperatively, there was no deterioration subjectively, with a persistent −1 limitation of right eye adduction and a matching −1 limitation of left eye abduction created by the lateral rectus posterior fixation suture. In primary position at distance fixation there was a 4Δ exophoria, with minimal recurrence of exotropia in left gaze (10Δ ) and 4Δ of esophoria on right gaze. Diplopia scores were much improved; from 100 to 24 using the Goldmann test, from 92 to 12 by cervical range of motion evaluation, and from 84 to 20 on the Diplopia Questionnaire. When asked to rate his improvement from 0 (no improvement) to 100 (complete cure), he gave a score of 90%.

Case 2

A 71-year-old man presented with horizontal diplopia following scleral buckle surgery for retinal detachment 6 years previously and had been managed with base in prisms. On examination there was a −1 limitation of adduction in the affected ri ght eye (Figure 3A). In primary position at distance fixation there was an intermittent exotropia measuring 16Δ with a 3Δ right hypophoria. The exotropia was similar in left gaze but reduced to 2Δ of exophoria in right gaze. Diplopia scores were 68 on the Diplopia Questionnaire but only 20 using the cervical range of motion method. The relatively low score using the cervical range of motion method was noted to be the result of intermittent fusion. Quantification of diplopia by Goldmann was not performed.

FIG 3.

A, Case 2, showing lag of adduction of the affected right eye preoperatively caused by restriction due to previous scleral buckle surgery. The adduction of the right eye is unbalanced with the abduction of the left eye (arrows), creating the incomitant exotropia. B, 6 weeks postoperatively, the recession of the left lateral rectus muscle with lateral rectus posterior fixation suture has induced the matching lag of abduction of the left eye, now balanced with the continued limited adduction of the right eye (arrows).

The left lateral rectus muscle was recessed 9 mm on an adjustable suture, placing a posterior fixation suture 17 mm back from the original insertion, as described above. At adjustment, the patient had a 4Δ esotropia in the distance and a 4Δ exophoria at near and so the sutures were tied off.

Six weeks postoperatively, the patient was orthotropic at distance and near fixation and in lateral gaze positions. The horizontal phoria measured 3Δ exophoria in primary position, zero in right gaze, and 3Δ esophoria in left gaze. The small right hypophoria persisted, ranging from 2Δ to 6Δ, but this could be fused easily. Ductions were well matched into left gaze, with the −1 limitation of adduction in the affected right eye now matched by a −1 limitation of abduction in the left eye induced by the lateral rectus posterior fixation suture (Figure 3B). The patient no longer needed prism glasses.

Thirteen months following surgery, the patient had no symptoms of diplopia. In primary position at distance fixation there was 1Δ of exophoria with no deviation on right gaze. The −1 limitation of left eye abduction induced by the posterior fixation suture was still present. Diplopia scores had improved from 68 to 20 on the Diplopia Questionnaire and remained stable and low on the cervical range of motion method (20 vs 24).

Case 3

A 51-year-old woman underwent endoscopic sinus surgery and developed horizontal diplopia in right gaze. She subsequently underwent medial orbital wall repair but without improvement in her diplopia. On examination she had a −2 limitatio n of adduction in the affected left eye. In primary position there was 6Δ exophoria at distance fixation, but there was no manifest exotropia. The patient had a 16Δ exotropia in right gaze and 2Δ of esodeviation in left gaze. Quantification of diplopia was not performed preoperatively in part because the preoperative visit predated the development of Cervical Range of Motion and Diplopia Questionnaire methods. Goldmann testing was not performed on this patient. The patient reported no diplopia in primary or reading, but became aware of diplopia approximately 20 degrees into right gaze.

The right lateral rectus muscle was recessed 4 mm using a fixed absorbable suture. The lateral rectus posterior fixation suture was placed 19 mm back from the original insertion, as described above, without creating the slits because adjustment was not planned. This case predated cases 1 and 2 and was performed before our adjustable technique was developed.

Six weeks postoperatively, the patient was orthophoric at distance and near and in lateral gaze positions, except for 4Δ exophoria in right gaze. Ductions were well matched into right gaze, with the −2 limitation of adduction in the le ft eye matched by the −1 limitation of abduction in the right eye induced by the lateral rectus posterior fixation suture.

Eight months following surgery, the patient reported no symptoms of diplopia in daily activities. On examination, the −1 limitation of ab duction in the right eye induced by the lateral rectus posterior fixation suture was maintained, matching the −2 limitation of abduction of the affected left eye. There had been no deterioration 22 months following surgery, with diplopia scores of 0 on both cervical range of motion method and the Diplopia Questionnaire. Her diplopia in right gaze had completely resolved.

Discussion

We have described a series of 3 cases where a posterior fixation suture on the lateral rectus muscle was used to address an incomitant exodeviation. In 2 of these cases, an adjustable recession was incorporated into the technique, although adjustment was not needed in these particular cases. In all cases, the lateral rectus posterior fixation suture induced the matching −1 limitation of abduction, with resulting improvement in incomitance of the exotropia. There were improvements in head posture and improved fields of single binocular vision.

The use of a posterior fixation suture on the lateral rectus muscle has only rarely been described previously.4,6-8,17 Previous clinical indications have included medial rectus weakness,8 nystagmus with head position,7 and dissociated horizontal deviation (DHD).17,18 We are unaware of a previous description of an adjustable suture technique for recessing the lateral rectus muscle with simultaneous posterior fixation suture. We have also successfully performed this technique of lateral rectus posterior fixation suture with adjustable recession in cases of DHD and plan to report these results separately.

Using a posterior fixation suture on the lateral rectus muscle is particularly appealing when the deviation is small in primary position because larger recessions to address lateral gaze deviation may result in overcorrection of primary gaze. Case 3 illustrates how a small recession can be combined with a posterior fixation suture to achieve minimal change in alignment in primary position and marked changes in lateral gaze, without creating an overcorrection in primary position.

Hoover19 has described an adjustable recession of the inferior rectus muscle with posterior fixation suture, but his technique requires untying the posterior fixation suture at the time of adjustment to allow adjustment of the recession, whereas our technique allows adjustment of the recession directly without untying the posterior fixation suture. We have also applied our adjustable recession with a posterior fixation suture to the medial rectus, inferior rectus and superior rectus.

An alternative approach to the posterior fixation suture with adjustable recession is the combined resection-recession procedure on the same muscle, where the resected muscle is reattached to the eye using an adjustable hang-back approach.9,20,21 One reason we prefer the adjustable recession with posterior fixation technique is that it likely minimizes the risk of late slippage, particularly for the inferior rectus. Indeed, Dawson and colleagues9 reported one slipped inferior rectus using the resection-recession adjustable method and Bock and colleagues20 did not apply the adjustable component of the technique to any inferior rectus muscle.

The weaknesses of our study include the small number of cases and the lack of a control group, making it difficult to conclude whether or not the posterior fixation suture technique we describe is truly superior to alternative surgical procedures such as a recession-resection procedure.9,20,21 The novel technique we describe of placing a posterior fixation suture through the middle third of the muscle and tying the posterior fixation suture not so tight to preclude postoperative adjustment of the recession may be less effective than suturing the superior and inferior borders of the muscle to the sclera, but our results suggest that the approach we describe was effective. In conclusion, a posterior fixation suture on the lateral rectus muscle, with an adjustable recession, is useful in addressing incomitant exodeviations.

Literature Search

PubMed was searched, without date restrictions, using the following terms and combinations: posterior fixation suture AND adjustable recession; faden AND adjustable recession; posterior fixation suture AND adjustable; faden AND adjustable; lateral rectus posterior fixation suture; and lateral rectus faden.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY015799 and EY018810 (JMH), Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, NY (JMH as Olga Keith Weiss Scholar and an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology, Mayo Clinic), and Mayo Foundation, Rochester, Minnesota.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.de Decker W. The Faden operation: When and how to do it. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK. 1981;101:264–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guyton DL. The posterior fixation procedure: Mechanism and indications. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1985;25:79–88. doi: 10.1097/00004397-198502540-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckley EG, Meekins BB. Fadenoperation for the management of complicated incomitant vertical strabismus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;105:304–12. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harcourt B. Faden operation (posterior fixation sutures) Eye. 1988;2:36–40. doi: 10.1038/eye.1988.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott AB. The Faden operation: Mechanical effects. Am Orthopt J. 1977;27:44–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyons CJ, Fells P, Lee JP, McIntyre A. Chorioretinal scarring following the Faden operation. A retrospective study of 100 procedures. Eye. 1989;3:401–3. doi: 10.1038/eye.1989.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark RA, Isenberg SJ, Rosenbaum AL, Demer JL. Posterior fixation sutures: A revised mechanical explanation for the Faden operation based on rectus extraocular muscle pulleys. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:702–14. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00356-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mojon DS. Minimally invasive strabismus surgery for rectus muscle posterior fixation. Ophthalmologica. 2009;223:111–15. doi: 10.1159/000180279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson E, Boyle N, Taherian K, Lee JP. Use of the combined recession and resection of a rectus muscle procedure in the management of incomitant strabismus. J AAPOS. 2007;11:131–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Del Monte MA. Adjustable Suture Strabismus Techniques. In: Del Monte MA, Archer SM, editors. Atlas of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus Surgery. Churchill Livingstone; New York, New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Monte MA. Special Muscle Procedures. In: Del Monte MA, Archer SM, editors. Atlas of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus Surgery. Churchill Livingstone; New York, New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott AB, Kraft SP. Botulinum toxin injection in the management of lateral rectus paresis. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:676–83. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)33982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams WE, Hatt SR, Leske DA, Holmes JM. Comparison of a diplopia questionnaire to the Goldmann diplopia field. J AAPOS. 2008;12:247–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodruff G, O'Reilly C, Kraft SP. Functional scoring of the field of binocular single vision in patients with diplopia. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:1554–61. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)33247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes JM, Leske DA, Kupersmith MJ. New methods for quantifying diplopia. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:2035–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatt SR, Leske DA, Holmes JM. Comparing methods of quantifying diplopia. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:2316–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero-Apis D, Castellanos-Bracamontes A. Dissociated horizontal deviation: Clinical findings and surgical results in 20 patients. Binocul Vis Quart. 1992;7:173–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson ME, Hutchinson AK, Saunders RA. Outcomes from surgical treatment for dissociated horizontal deviation. J AAPOS. 2000;4:94–101. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2000.103437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoover DL. Results of a combined adjustable recession and posterior fixation suture of the same vertical rectus muscle for incomitant vertical strabismus. J AAPOS. 1998;2:336–9. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(98)90030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bock CJ, Jr., Buckley EG, Freedman SF. Combined resection and recession of a single rectus muscle for the treatment of incomitant strabismus. J AAPOS. 1999;3:263–8. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(99)70020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott AB. Posterior fixation: Adjustable and without posterior sutures. In: Lennerstrand G, editor. Proceedings VIIth Congress International Strabismological Association. CRC Press, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]