Abstract

Objective

Bipolar disorder is highly comorbid with substance use disorders, and this comorbidity may be associated with a more severe course of illness, but the impact of comorbid substance abuse on recovery from major depressive episodes in these patients has not been adequately examined. The authors hypothesized that comorbid drug and alcohol use disorders would be associated with longer time to recovery in patients with bipolar disorder.

Method

Subjects (N=3,750) with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder enrolled in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) were followed prospectively for up to 2 years. Prospectively observed depressive episodes were identified for this analysis. Subjects with a past or current drug or alcohol use disorder were compared with those with no history of drug or alcohol use disorders on time to recovery from depression and time until switch to a manic, hypomanic, or mixed episode.

Results

During follow up, 2,154 subjects developed a new-onset major depressive episode; of these, 457 subjects switched to a manic, hypomanic, or mixed episode prior to recovery. Past or current substance use disorder did not predict time to recovery from a depressive episode relative to no substance use comorbidity. However, those with current or past substance use disorder were more likely to experience switch from depression directly to a manic, hypomanic, or mixed state.

Conclusions

Current or past substance use disorders were not associated with longer time to recovery from depression but may contribute to greater risk of switch into manic, mixed, or hypomanic states. The mechanism conferring this increased risk merits further study.

People with bipolar disorder are at extraordinarily high risk for co-occurring substance use disorders. The lifetime prevalence of substance use disorder is higher in bipolar disorder than in any other psychiatric illness, with lifetime rates in epidemiological and clinical samples ranging from 40%–60% (1–3). This association is of great clinical significance, as it has generally been thought that co-occurring substance abuse worsens the course of illness. More recently, however, reports have suggested that some people with bipolar disorder and substance abuse may do as well—or sometimes better—than those with no substance abuse history (4–6).

Several reports have suggested that comorbid bipolar disorder and substance use disorder are marked by more severe symptoms, more frequent mood episodes, more suicide attempts, medical comorbidity, lower functioning, and lower life satisfaction (7–14). Even low levels of alcohol use have been associated with more symptoms in bipolar disorder, suggesting that any drinking among patients with bipolar disorder—not merely in those with substance use disorders—may be associated with a more severe course of illness (4). It is not known, however, whether substance use disorders are the cause of this increased morbidity or rather that substance use disorders are prevalent in patients with a different or more severe form of bipolar disorder. Moreover, it remains unclear whether there is a causal relationship between the substance use disorder and worse outcome in patients with bipolar disorder, since several studies suggest that the relationship between the clinical course of both mood disorders and the substance use disorder is somewhat complex. For example, patients with bipolar disorder who develop substance use disorder prior to the onset of their first mood episode (sometimes called secondary bipolar disorder) may have a less severe course of illness than those whose substance use disorder develops after the onset of their mood disorder (5, 6).

In a study of subjects admitted to an inpatient unit for a first manic or mixed episode who were followed prospectively for up to 5 years, subjects for whom bipolar disorder onset was later than their substance use disorder were more likely to recover from their initial episode of mania than those for whom bipolar disorder manifest first, and this was found both in those with alcohol dependence and those with cannabis dependence (5). Similarly, in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD), a longitudinal, observational study of bipolar disorder, subjects with secondary bipolar disorder also had a less severe course of illness, but when the age of onset of the mood disorder was controlled there were no differences in severity (15). This finding suggests that while comorbidity is more common in early onset bipolar disorder, differences in illness course are perhaps more related to the severity of the underlying illness than to the underlying substance use disorder comorbidity.

Some findings suggest that the propensity for individuals with bipolar disorder to develop a substance use disorder might be associated with differences in outcome. A past but not current history of substance use disorder, for example, appears to be associated with more morbidity in co-occurring bipolar disorder, suggesting that morbidity may not be due to the direct temporal effects of intoxication. In a study of the first 1,000 subjects enrolled in STEP-BD, those with a past history of substance use disorder (i.e., not meeting criteria for a substance use disorder) reported more symptoms of depression and lower life satisfaction than those with no history of substance use disorder (10). In the same vein, Goldberg et al. (16) reported that subjects admitted to an inpatient unit with mania and past or recent (but not current) substance abuse were less likely to achieve remission of their episodes, suggesting that those with comorbid substance use disorder histories had a more severe form of bipolar disorder. These data suggest, perhaps, that people with bipolar disorder who are prone to develop substance use disorder may have a more severe form of bipolar disorder than do people who never develop them.

The impact of drug and alcohol use disorders on the prospective course of depressive episodes in bipolar disorder is not well studied, and outcomes specifically examining the relationship between substance use disorder and depression in bipolar disorder are lacking. While people with bipolar disorder may be more likely to be depressed if they have a current or past history of substance use disorder, it is not known whether this comorbidity leads to worse outcomes in treatment. In this large, longitudinal, prospective study of subjects with bipolar disorder, we hypothesized that subjects with bipolar disorder with current alcohol or drug use disorders would be less likely to recover from a new-onset episode of major depression than would subjects with no alcohol or drug use disorder history, and that subjects with past (but not current) alcohol or drug use disorders would also be less likely to recover from a new-onset episode of major depression.

Method

Study Overview

STEP-BD was a multicenter “effectiveness” study conducted in the United States between 1999 and 2005 that evaluated prospective outcomes among individuals with bipolar disorder. Methods for the STEP-BD study as a whole are detailed elsewhere (17).

Participants

Study participation was offered to all patients with bipolar disorder seeking outpatient treatment at one of the participating study sites. Entry criteria included meeting DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified, cyclothymia, or schizoaffective disorder bipolar type and ability to provide written informed consent. For individuals age 15–17, written assent was also required from parent or guardian. Hospitalized individuals were eligible to enter following discharge.

Assessments

Bipolar disorder diagnosis was determined using mood and psychosis modules from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) as incorporated in the Affective Disorders Evaluation, and confirmed by a second clinical rater using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (18). Comorbid axis I diagnoses, including current and past alcohol use disorders and drug use disorders, were also determined by using the MINI. At each visit, clinicians assigned current mood status based upon a clinical monitoring form (19) that assesses DSM-IV criteria for depressive, manic, hypomanic, or mixed states in the prior 14 days. Each criterion is scored on a 0–2 scale, in which 1 represents “threshold” by DSM-IV mood episode criteria; fractional scores are used to indicate subthresh-old symptoms. For example, a patient with insomnia less than half the time would receive a “0.5” rather than a “1” on the sleep item.

Additional details of patient retrospective course on entering STEP-BD were collected by the clinician with the Affective Disorders Evaluation, including proportion of time in the preceding year with depressive, manic, and anxious symptoms as well as number of episodes of each type.

Intervention

Study clinicians in STEP-BD were trained to use model practice procedures, which included published pharmacotherapy guidelines (17), but they could prescribe any treatment that they felt to be indicated. Elsewhere, we have reported high concordance between treatment selection and guideline recommendations, indicating that patients received standard-of-care treatment when entering STEP-BD (20). At trial entry, however, few subjects were receiving pharmacologic treatment for substance use disorder (21).

Outcomes

Because STEP-BD was intended to approximate clinical practice, participants were seen as frequently as clinically indicated. Clinical status, assessed at each follow-up visit with a clinical monitoring form, was used to define the mood states that represent the primary outcome measure. Remission (defined in other STEP-BD reports as recovery or durable recovery) was defined as no more than two syndromal features of mania, hypomania, or depression for at least 8 weeks, consistent with standard DSM-IV criteria for partial or full remission and with criteria used in the prior NIMH Collaborative Study of Depression (22). Switch was defined as meeting full DSM-IV criteria for a manic, hypomanic, or mixed episode on any one follow-up visit.

Statistical Analysis

In total, 4,107 subjects entered STEP-BD, including 3,750 with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder. From these 3,750, we identified those who experienced a prospective depressive episode and examined time until recovery (i.e., remission). Data were right-censored for subjects lost to follow-up prior to recovery and those who experienced a switch into a manic, hypomanic, or mixed state prior to recovery. (To examine the impact of censoring at time of switch, a secondary analysis examined time-to-switch directly, with results censored at dropout or recovery from depression). A post hoc analysis of time to recovery regardless of switch in mood states was also performed. Cox regression models were used to examine the association between substance use status and time to recovery, with the Efron method for resolving tied failures. Proportional hazards assumption was examined using visual inspection of hazard plots as well as formally tested by incorporating a term for covariate-by-time interaction into the Cox models. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated for illustrative purposes.

All analyses used Stata 10.0 (College Station, Tex.).

Results

Baseline evaluation was completed on 4,107 subjects. Of these, 3,750 had a diagnosis of bipolar I or bipolar II disorder, and 3,376 completed at least one follow-up visit. Major depressive episodes were observed in 2,234 subjects during the follow-up period, of whom 2,154 completed at least one follow-up visit after becoming depressed and formed the primary risk cohort examined here. A total of 1,207 subjects (56.0%) had no history of an alcohol use disorder, 693 (32.2%) had a past alcohol use disorder, and 254 (11.8%) had a current alcohol use disorder. A total of 1,528 subjects (70.9%) had no history of a drug use disorder, 468 (21.7%) had a past drug use disorder, and 158 (7.3%) had a current drug use disorder. The median age at onset of an alcohol use disorder was 18 years (interquartile range=15–20) with a mean of 18.6 years (SD=7.5). The median age of onset of a drug use disorder was 18 years (interquartile range=15–20) with a mean of 19.0 years (SD=6.3). Demographic characteristics of each group (alcohol and drug use disorder in past versus current versus never) are described in Table 1 and Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Bipolar Disorder Patients Participating in STEP-BD Who Experienced a New-Onset Depressive Episode, by Alcohol Use Disorder History

| Variable | Alcohol Use Disorder History |

Analysis |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never (N=1,207) | Past (N=693) | Current (N=254) | All (N=2,154) | χ2 | p | |||||||||

| Total N | N | % | Total N | N | % | Total N | N | % | Total N | N | % | |||

| Gender | 1,207 | 693 | 254 | 2,154 | 21.88 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Male | 451 | 37.4 | 295 | 42.6 | 134 | 52.8 | 880 | 40.9 | ||||||

| Female | 756 | 62.6 | 398 | 57.4 | 120 | 47.2 | 1,274 | 59.1 | ||||||

| Bipolar type | 1,207 | 693 | 254 | 2,154 | 2.96 | 0.23 | ||||||||

| Bipolar I disorder | 816 | 67.6 | 493 | 71.1 | 180 | 70.9 | 1,489 | 69.1 | ||||||

| Bipolar II disorder | 391 | 32.4 | 200 | 28.9 | 74 | 29.1 | 665 | 30.9 | ||||||

| Race | 1,207 | 693 | 254 | 2,154 | 17.90 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| White | 1,074 | 89.0 | 650 | 93.8 | 242 | 95.3 | 1,966 | 91.3 | ||||||

| Non-white | 133 | 11.0 | 43 | 6.2 | 12 | 4.7 | 188 | 8.7 | ||||||

| Married | 1,116 | 684 | 250 | 2,050 | 10.73 | 0.005 | ||||||||

| Yes | 436 | 39.1 | 266 | 38.9 | 72 | 28.8 | 774 | 37.8 | ||||||

| No | 680 | 60.9 | 418 | 61.1 | 178 | 71.2 | 1,276 | 62.2 | ||||||

| Employed | 1,116 | 684 | 250 | 2,050 | 6.27 | 0.043 | ||||||||

| Yes | 464 | 41.6 | 307 | 44.9 | 125 | 50 | 896 | 43.7 | ||||||

| No | 652 | 58.4 | 377 | 55.1 | 125 | 50 | 1,154 | 56.3 | ||||||

| Current anxiety | 1,207 | 693 | 254 | 2,154 | 67.64 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 401 | 33.2 | 335 | 48.3 | 140 | 55.1 | 876 | 40.7 | ||||||

| No | 806 | 66.8 | 358 | 51.7 | 114 | 44.9 | 1,278 | 59.3 | ||||||

| Rapid cycling in past year | 1,207 | 693 | 254 | 2,154 | 12.19 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| Yes | 585 | 48.5 | 324 | 46.8 | 149 | 58.7 | 1,058 | 49.1 | ||||||

| No | 622 | 51.5 | 369 | 53.2 | 105 | 41.3 | 1,096 | 50.9 | ||||||

| History of suicide attempt | 1,160 | 683 | 245 | 2,088 | 18.26 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 423 | 36.5 | 305 | 44.7 | 117 | 47.8 | 845 | 40.5 | ||||||

| No | 737 | 63.5 | 378 | 55.3 | 128 | 52.2 | 1,243 | 59.5 | ||||||

| Total N | Mean | SD | Total N | Mean | SD | Total N | Mean | SD | Total N | Mean | SD | F | p | |

| Age | 1,207 | 40.35 | 12.84 | 693 | 41.82 | 11.32 | 254 | 35.29 | 10.90 | 2,154 | 40.23 | 12.30 | 27.22 | <0.0001 |

| Age at onset | 1,177 | 17.86 | 9.26 | 683 | 15.68 | 7.61 | 249 | 14.79 | 6.52 | 2,109 | 16.79 | 8.55 | 22.94 | <0.0001 |

| Age at onset of mania | 1,145 | 22.55 | 10.50 | 657 | 20.22 | 9.42 | 239 | 18.66 | 8.36 | 2,041 | 21.34 | 10.03 | 21.96 | <0.0001 |

| Age at onset of depression | 1,117 | 18.69 | 9.77 | 654 | 16.68 | 8.27 | 236 | 15.54 | 7.14 | 2,007 | 17.67 | 9.10 | 18.64 | <0.0001 |

| Depressed days/year | 1,181 | 50.70 | 28.48 | 675 | 51.03 | 28.45 | 247 | 56.10 | 27.78 | 2,103 | 51.44 | 28.43 | 4.25 | 0.014 |

| Anxious days/year | 1167 | 38.71 | 34.17 | 665 | 40.94 | 33.70 | 244 | 47.40 | 34.56 | 2076 | 40.44 | 34.16 | 7.73 | 0.0005 |

| Irritable days/year | 1170 | 34.33 | 31.08 | 670 | 35.65 | 30.32 | 243 | 43.69 | 32.78 | 2083 | 35.85 | 31.16 | 9.79 | 0.0001 |

| Elevated days/year | 1167 | 18.59 | 20.59 | 669 | 19.16 | 19.49 | 246 | 24.28 | 21.73 | 2082 | 19.45 | 20.45 | 8.98 | 0.0001 |

TABLE 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Bipolar Disorder Patients Participating in STEP-BD Who Experienced a New-Onset Depressive Episode, by Drug Use Disorder History

| Variable | Drug Use Disorder History |

Analysis |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never (N=1,528) | Past (N=468) | Current (N=158) | All (N=2,154) | χ2 | p | |||||||||

| Total N | N | % | Total N | N | % | Total N | N | % | Total N | N | % | |||

| Gender | 1,528 | 468 | 158 | 2,154 | 13.10 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Male | 595 | 38.9 | 201 | 42.9 | 84 | 53.2 | 880 | 40.9 | ||||||

| Female | 933 | 61.1 | 267 | 57.1 | 74 | 46.8 | 1,274 | 59.1 | ||||||

| Bipolar type | 1,528 | 468 | 158 | 2,154 | 7.14 | 0.028 | ||||||||

| Bipolar I disorder | 1,036 | 67.8 | 331 | 70.7 | 122 | 77.2 | 1,489 | 69.1 | ||||||

| Bipolar II disorder | 492 | 32.2 | 137 | 29.3 | 36 | 22.8 | 665 | 30.9 | ||||||

| Race | 1,528 | 468 | 158 | 2,154 | 10.16 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| White | 1,378 | 90.2 | 445 | 95.1 | 143 | 90.5 | 1,966 | 91.3 | ||||||

| Non-white | 150 | 9.8 | 23 | 4.9 | 15 | 9.5 | 188 | 8.7 | ||||||

| Married | 1,434 | 459 | 157 | 2,050 | 12.94 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| Yes | 569 | 39.7 | 164 | 35.7 | 41 | 26.1 | 774 | 37.8 | ||||||

| No | 865 | 60.3 | 295 | 64.3 | 116 | 73.9 | 1,276 | 62.2 | ||||||

| Employed | 1,434 | 459 | 157 | 2,050 | 0.15 | 0.930 | ||||||||

| Yes | 624 | 43.5 | 204 | 44.4 | 68 | 43.3 | 896 | 43.7 | ||||||

| No | 810 | 56.5 | 255 | 55.6 | 89 | 56.7 | 1,154 | 56.3 | ||||||

| Current anxiety | 1,528 | 468 | 158 | 2,154 | 51.56 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 550 | 36.0 | 235 | 50.2 | 91 | 57.6 | 876 | 40.7 | ||||||

| No | 978 | 64.0 | 233 | 49.8 | 67 | 42.4 | 1,278 | 59.3 | ||||||

| Rapid cycling in past year | 1,528 | 468 | 158 | 2,154 | 7.71 | 0.021 | ||||||||

| Yes | 723 | 47.3 | 252 | 53.8 | 83 | 52.5 | 1,058 | 49.1 | ||||||

| No | 805 | 52.7 | 216 | 46.2 | 75 | 47.5 | 1,096 | 50.9 | ||||||

| History of suicide attempt | 1,473 | 459 | 156 | 2,088 | 24.82 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 546 | 37.1 | 223 | 48.6 | 76 | 48.7 | 845 | 40.5 | ||||||

| No | 927 | 62.9 | 236 | 51.4 | 80 | 51.3 | 1,243 | 59.5 | ||||||

| Total N | Mean | SD | Total N | Mean | SD | Total N | Mean | SD | Total N | Mean | SD | F | p | |

| Age | 1,528 | 41.08 | 12.77 | 468 | 39.42 | 10.49 | 158 | 34.37 | 10.73 | 2,154 | 40.23 | 12.30 | 23.34 | <0.0001 |

| Age at onset | 1,488 | 17.72 | 9.05 | 465 | 14.48 | 6.54 | 156 | 14.81 | 7.23 | 2,109 | 16.79 | 8.55 | 30.83 | <0.0001 |

| Age at onset of mania | 1,445 | 22.56 | 10.52 | 444 | 18.32 | 7.97 | 152 | 18.65 | 8.12 | 2,041 | 21.34 | 10.03 | 37.78 | <0.0001 |

| Age at onset of depression | 1,415 | 18.55 | 9.61 | 442 | 15.56 | 7.29 | 150 | 15.55 | 7.43 | 2,007 | 17.67 | 9.10 | 23.21 | <0.0001 |

| Depressed days/year | 1,492 | 51.01 | 28.58 | 461 | 52.92 | 28.68 | 150 | 51.20 | 26.11 | 2,103 | 51.44 | 28.42 | 0.79 | 0.452 |

| Anxious days/year | 1,468 | 39.37 | 34.10 | 459 | 42.43 | 34.17 | 149 | 44.93 | 34.27 | 2,076 | 40.44 | 34.16 | 3.33 | 0.036 |

| Irritable days/year | 1,475 | 34.62 | 31.04 | 458 | 38.09 | 30.89 | 150 | 41.10 | 32.49 | 2,083 | 35.85 | 31.16 | 4.80 | 0.008 |

| Elevated days/year | 1,474 | 18.00 | 19.97 | 458 | 22.46 | 21.12 | 150 | 24.48 | 21.39 | 2,082 | 19.45 | 20.45 | 14.14 | <0.0001 |

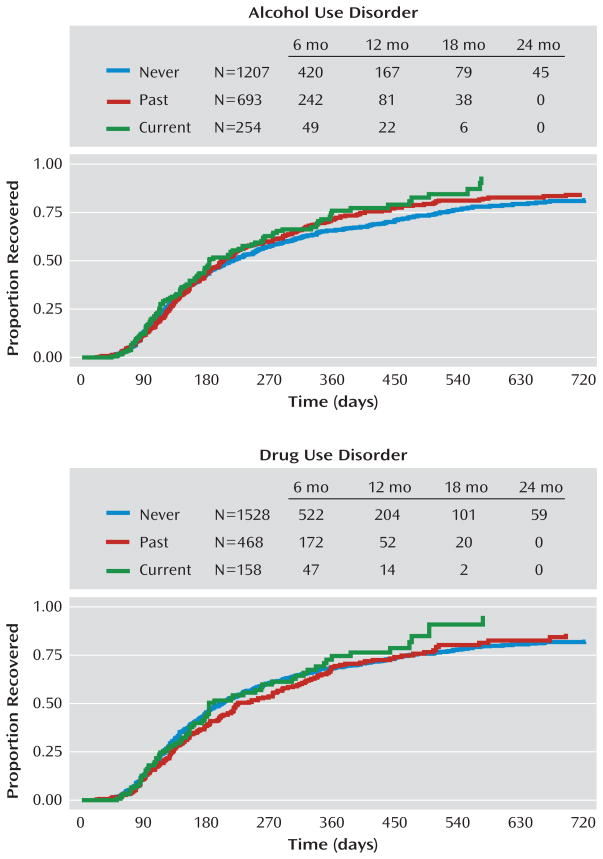

Survival analysis was used to examine the time to recovery for each group, with alcohol use disorders examined separately from drug use disorders. Median time to recovery was 182 days for those with a current alcohol use disorder, 201 days for a past alcohol use disorder, and 215 days for those with no history of alcohol use disorders. These differences were not significant, with no difference between those with current versus no history of alcohol use disorder (χ2=3.40, p=0.065), past versus no history of alcohol use disorder (χ2=1.08, p=0.299), or current versus past alcohol use disorder (χ2=1.18, p=0.278). Median time to recovery was 184 days for those with current drug use disorder, 224 days for past drug use disorder, and 200 days for no history of drug use disorder, with no significant difference in time to recovery between those with current versus no history of drug use disorder (χ2=0.59, p=0.442), past versus no history of drug use disorder (χ2=1.21, p=0.271), or current versus past drug use disorder (χ2=2.20, p=0.138). Survival curves are found in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Time to Recovery From a Prospectively Observed Depressive Episode in Bipolar Disorder Patients Participating in STEP-BD, by Substance Use Disorder History

Switch to a manic, hypomanic, or mixed state prior to recovery from the index episode of depression was prospectively observed in 457 (21.2%) of the subjects. Likelihood of switch prior to recovery was significantly associated with current and past alcohol use disorder compared to no history (p=0.001 and p=0.01, respectively). Likelihood of switch was significantly associated with current and past drug use disorder compared to no history (p=0.005 and p=0.05, respectively). Survival curves for time to switch are found in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Time Until Switch From a Prospectively Observed Depressive Episode to a Manic, Hypomanic, or Mixed Episode in Bipolar Disorder Patients Participating in STEP-BD, by Substance Use Disorder History

Rapid cycling (≥4 mood episodes) in the past year was significantly associated with past and current alcohol use disorders (p=0.001 and p=0.009, respectively) but not with past or current drug use disorders (p=0.206 and p=0.141, respectively). When rapid cycling was added to the Cox regression model as a covariate, there was minimal change (<10%) in the hazard ratios for all of these groups; therefore, rapid cycling does not appear to be a confounder of the relationship between past and current substance use disorder and increased likelihood of switch. A post hoc analysis of time to recovery not censoring subjects who switched mood states (e.g., including subjects who switched to mania prior to achieving recovery) did not find a significant difference between groups (results not shown.) There were no differences between groups in the use of lithium, valproate, or antipsychotic medications. Lamotrigine use was somewhat lower in those with current drug use disorder (p=0.028) with a tendency toward lower use in those with current alcohol use disorder (p=0.097). Antidepressant use was somewhat lower in those with current drug use disorder (p=0.038) with a tendency toward lower use in those with current alcohol use disorder (p=0.062). These results should be interpreted with caution, as we did not correct for multiple comparisons.

Results did not appear to be confounded by sociode-mographic or clinical features, including current DSM-IV anxiety disorder, age at onset, age at study entry, sex, education, or marital status. Incorporating these terms in the Cox regression models yielded change in the resulting hazard ratio of less than 10%.

Discussion

Time to recovery from a new-onset major depressive episode did not differ significantly for subjects with current or past alcohol or drug use disorders in this prospective, observational multisite study. This surprising finding is in contrast to the prevailing view that substance use disorders impair the ability to recover from depression. The lack of a difference is consistent, however, with findings from the NIMH Collaborative Depression Study, which reported similar outcomes for subjects with bipolar disorder and comorbid alcohol use disorders (Ostacher et al., unpublished). Lower use of antidepressants and lamotrigine in subjects with drug use disorders (and to a lesser extent alcohol use disorders) would be expected to bias those groups toward longer time to recovery, but this did not appear to be the case in this cohort.

Current and past alcohol use disorder and drug use disorder, however, were associated with an increased likelihood of switch to mania, hypomania, or mixed states prior to recovery from a major depressive episode. It is reasonable to expect that those with current alcohol use disorder or drug use disorder would be more likely to switch relative to those with a past history, but we found that current or past history conveyed a similar risk of switch. This raises the question of whether patients with any substance use disorder history may be more prone to mood instability, or, conversely, whether patients with more mood instability may be more likely to develop a substance use disorder. A post hoc analysis examining time to recovery including (rather than censoring) those who switched to a manic, hypomanic, or mixed state (and perhaps back to depression) prior to recovery, however, did not show a significant difference between groups with and without substance use disorder; overall episode length in spite of increased rates of switch was not longer in subjects with substance use disorder histories compared to those without.

The finding that the presence of substance use disorders in patients with bipolar disorder does not directly affect the length of depressive episodes in bipolar disorder are consistent with the findings of Strakowski et al. (5, 6) that some patients with bipolar disorder and co-occurring substance use disorders have a course of illness that is less severe than that of some patients with bipolar disorder and no substance use disorder comorbidity. Our results further suggest that patients with bipolar disorder and lifetime substance use disorder comorbidity—whether current or in the past—have inherent characteristics that may differentiate them from those without substance use disorder, including the propensity to switch from depression to manic, hypomanic, or mixed states. Similar switch rates prior to recovery from the index episode of depression in subjects with past and current substance use disorders suggests that the factors inherent in patients with bipolar disorder at risk for substance use disorders may also confer greater likelihood of switching; our data suggest that switching is not likely to occur as the direct result of current drug or alcohol use. Adding variables typically associated with both substance use disorder and worse outcome, including DSM-IV anxiety disorder, age at onset, age at study entry, sex, education, marital status, and rapid cycling in the past 12 months did not alter the results.

This study did not examine the relationship between the amount of substance use and outcome, and this is an important limitation of the study. Substance use disorders in DSM-IV are 12-month diagnoses; that is, they do not directly reflect the level of use at the time of diagnosis, and they do not account for the severity of use. Our study did not include measures of substance use severity, such as the Addiction Severity Index. It may be the case that level of alcohol and drug use present in this cohort may have been within a limited range and severity, with insufficient magnitude to interfere with recovery. It is also possible that subjects with current substance use disorder decreased their use during treatment, and this may in part explain their similarity to those with past substance use disorder. In addition, it is difficult to know whether the increased anxiety found in subjects with current substance use disorder is a result of drug or alcohol use or is a consequence of it.

The MINI is well validated and was chosen as the diagnostic tool in the study instead of the SCID to improve the feasibility of the study. It does not have a field for specific drug of abuse, however, and this is a limitation. Because of this, these data cannot be extrapolated to determine whether specific types of drug abuse are associated with the outcome we found.

Another aspect of the study worth noting is that this is a population of patients willing and able to comply with follow-up in a research study, and this may be a marker for treatment adherence and persistence. Substance use disorders in bipolar disorder are associated with lower adherence, but this may be mitigated overall in this group of treatment-seeking subjects who are able to comply with study protocol (23). These subjects were followed primarily in academic medical centers and may not be representative of the general population of patients with bipolar disorder. It is possible that patients with bipolar disorder and severe drug use disorder and alcohol use disorder were either not enrolled in the study after evaluation or were never referred.

It remains important to try to explain the lack of difference for depression outcomes. Patients with bipolar disorder are frequently complex in their presentation, with high rates of anxiety disorder, ADHD, substance abuse, and medical comorbidity. Multiple factors have been found to be associated with poor outcome in patients with bipolar disorder—most notably anxiety disorders—so it is quite important that clinicians be aware of prognostic indicators to best approach their patients (24). Drug and alcohol use is perceived to be a modifiable risk factor for poor outcome (unlike anxiety disorder comorbidity or family history, for example), so it is understandable that clinicians might focus on changing drug and alcohol use in an effort to improve treatment outcome. What these data suggest, however, is that alcohol and drug history, past or present, may not be a reliable indicator of outcome for recovery from major depressive episodes in bipolar disorder, and that a singular focus on substance use might be less useful, perhaps, than aggressive treatment of anxiety, a specific intervention to improve treatment adherence, or the implementation of an evidence-based psychosocial treatment for bipolar depression.

Most importantly, these findings suggest that treatment for bipolar depression should not be withheld from patients with co-occurring alcohol or drug use disorders, especially given that the prognosis for an episode of bipolar depression is no worse than for those with bipolar depression and no alcohol or drug use disorder, and that engaging them in treatment is important because of their overall severity. Further understanding of subgroup characteristics associated with outcomes in bipolar disorder is needed to direct patient care. In summary, a comorbid substance use disorder was not related to recovery from depression but was associated with increased risk of switch from depression into manic/hypomanic/mixed states. Current or lifetime substance use disorder conveyed similar risks. Even in the presence of a substance use disorder, it may be possible to help these bipolar patients with appropriate treatment of their acute bipolar state.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Ostacher has received research support from Pfizer; he has served on the advisory/consulting boards of Pfizer, Schering-Plough, and Concordant Rater Systems; he has received speaking fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Pfizer, and Massachusetts General Psychiatry Academy (w hose talks were supported in 2008 through independent medical education grants from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and Janssen). Dr. Perlis has received honoraria or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer. Dr. Nierenberg receives research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cederroth, Cyberonics, Eli Lilly, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Lichtwer, the National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression, NIMH, PamLabs, Pfizer, the Stanley Foundation, and Wyeth; he serves as an advisor or consultant to AstraZeneca, Basilea, Brain Cells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dainippon Sumitomo, Eli Lilly, EpiQ, Genaissance, GlaxoSmithKline, Innapharma, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Neuronetics, Novartis, Pfizer, PGx Health, Sepracor, Shire, Targacept, and Takeda; he receives speaking fees from Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Organon, Wyeth, and Massachusetts General Psychiatry Academy (w hose talks were supported in 2008 through independent medical education grants from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and Janssen); and he holds shares in Appliance Computing. Dr. Calabrese receives federal funding from the Department of Defense, Health Resources Services Administration, and NIMH; he receives research funding or grants from the following private industries or nonprofit funds: Cleveland Foundation, NARSAD, and Stanley Medical Research Institute; he receives research grants from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Cephalon, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Eli Lilly, and Lundbeck; he serves on the advisory boards of Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Forest, France Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, NeuroSearch, OrthoMcNeil, Repligen, Schering-Plough, Servier, Solvay/Wyeth, Takeda, and Supernus Pharmaceuticals; and he reports CME activities with AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, France Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Schering-Plough, and Solvay/Wyeth. Mr. Stange reports no financial relationships with commercial interests. Dr. Salloum has received research support from AstraZeneca, Abbott Laboratories, Ortho McNeil Pharm, Drug Abuse Sciences, Inc., Alkermese, Inc., Oy Contral Pharma, and Lipha Pharma; he has acted as a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Forest Laboratories, Cephalon, and AstraZeneca; and he has been an invited speaker by Abbott Laboratories and Sanofi Aventis. Dr. Weiss has received research support from Eli Lilly and company and has consulted to Titan Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Sachs serves on the speakers bureaus of Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Memory Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Wyeth; he serves as an advisory board member or consultant for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, CNS Response, Concordant Rater Systems, Elan Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Memory Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Novartis, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Repligen, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering Plough, Sepracor, Shire, Sigma-Tau, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth; and his spouse holds shares in Concordant Rater Systems.

This study was supported by grant K23AA016340-01A1 from the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (Dr. Ostacher), NIMH grant N01MH8001 (Dr. Sachs), and grants DA022288 and DA15968 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Dr. Weiss). STEP-BD was funded with Federal funds from NIMH under Contract N01MH80001. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIMH.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Rubinow DR, Holmes C, Abelson JM, Zhao S. The epidemiology of DSM-III-R bipolar I disorder in a general population survey. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1079–1089. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suppes T, Leverich GS, Keck PE, Nolen WA, Denicoff KD, Altshuler LL, McElroy SL, Rush AJ, Kupka R, Frye MA, Bickel M, Post RM. The Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network, II: demographics and illness characteristics of the first 261 patients. J Affect Disord. 2001;67:45–59. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00432-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Suppes T, Keck PE, Jr, Frye MA, Denicoff KD, Nolen WA, Kupka RW, Leverich GS, Rochussen JR, Rush AJ, Post RM. Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:420–426. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein BI, Velyvis VP, Parikh SV. The association between moderate alcohol use and illness severity in bipolar disorder: a preliminary report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:102–106. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Fleck DE, Adler CM, Anthenelli RM, Keck PE, Jr, Arnold LM, Amicone J. Effects of co-occurring cannabis use disorders on the course of bipolar disorder after a first hospitalization for mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:57–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Fleck DE, Adler CM, Anthenelli RM, Keck PE, Jr, Arnold LM, Amicone J. Effects of co-occurring alcohol abuse on the course of bipolar disorder following a first hospitalization for mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:851–858. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kemp DE, Gao K, Ganocy SJ, Caldes E, Feldman K, Chan PK, Conroy C, Bilali S, Findling RL, Calabrese JR. Medical and substance use comorbidity in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2009;116:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassidy F, Ahearn EP, Carroll BJ. Substance abuse in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:181–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salloum IM, Thase ME. Impact of substance abuse on the course and treatment of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2(3 pt 2):269–280. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.20308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss RD, Ostacher MJ, Otto MW, Calabrese JR, Fossey M, Wisniewski SR, Bowden CL, Nierenberg AA, Pollack MH, Salloum IM, Simon NM, Thase ME, Sachs GS. For STEP-BD investigators: does recovery from substance use disorder matter in patients with bipolar disorder? J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:730–735. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marangell LB, Bauer MS, Dennehy EB, Wisniewski SR, Allen MH, Miklowitz DJ, Oquendo MA, Frank E, Perlis RH, Martinez JM, Fagiolini A, Otto MW, Chessick CA, Zboyan HA, Miyahara S, Sachs G, Thase ME. Prospective predictors of suicide and suicide attempts in 1,556 patients with bipolar disorders followed for up to 2 years. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(5 pt 2):566–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaffee WB, Griffin ML, Gallop R, Meade CS, Graff F, Bender RE, Weiss RD. Depression precipitated by alcohol use in patients with co-occurring bipolar and substance use disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:171–176. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sajatovic M, Ignacio RV, West JA, Cassidy KA, Safavi R, Kilbourne AM, Blow FC. Predictors of nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder receiving treatment in a community mental health clinic. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fossey MD, Otto MW, Yates WR, Wisniewski SR, Gyulai L, Allen MH, Miklowitz DJ, Coon KA, Ostacher MJ, Neel JL, Thase ME, Sachs GS, Weiss RD STEP-BD Investigators. Validity of the distinction between primary and secondary substance use disorder in patients with bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 STEP-BD participants. Am J Addict. 2006;15:138–143. doi: 10.1080/10550490500528423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg JF, Garno JL, Leon AC, Kocsis JH, Portera L. A history of substance abuse complicates remission from acute mania in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:733–740. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, Bauer M, Miklowitz D, Wisniewski SR, Lavori P, Lebowitz B, Rudorfer M, Frank E, Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Bowden C, Ketter T, Marangell L, Calabrese J, Kupfer D, Rosenbaum JF. Rationale, design, and methods of the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD) Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:1028–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sachs GS, Guille C, McMurrich SL. A clinical monitoring form for mood disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4:323–327. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dennehy EB, Bauer MS, Perlis RH, Kogan JN, Sachs GS. Concordance with treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder: data from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2007;40:72–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon NM, Otto MW, Weiss RD, Bauer MS, Miyahara S, Wisniewski SR, Thase ME, Kogan J, Frank E, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, Sachs GS, Pollack MH STEP-BD Investigators. Pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder and comorbid conditions: baseline data from STEP-BD. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:512–520. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000138772.40515.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Coryell W, Endicott J, Mueller TI. Bipolar I: a five-year prospective follow-up. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181:238–245. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldessarini RJ, Perry R, Pike J. Factors associated with treatment nonadherence among US bipolar disorder patients. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23:95–105. doi: 10.1002/hup.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otto MW, Simon NM, Wisniewski SR, Miklowitz DJ, Kogan JN, Reilly-Harrington NA, Frank E, Nierenberg AA, Marangell LB, Sagduyu K, Weiss RD, Miyahara S, Thase ME, Sachs GS, Pollack MH STEP-BD Investigators. Prospective 12-month course of bipolar disorder in out-patients with and without comorbid anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:20–25. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]