Abstract

Tobacco dependence is the leading cause of death in persons with psychiatric and substance use disorders. This has lead to interest in the development of pharmacological and behavioral treatments for tobacco dependence in this subset of smokers. However, there has been little attention paid to the development of tobacco-free environments in psychiatric institutions despite the creation of smoke-free psychiatric hospitals mandated by the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Health Organizations (JCAHO) in 1992. This review article addresses the reasons why tobacco should be excluded from psychiatric and addictions treatment settings, and strategies that can be employed to initiate and maintain tobacco-free psychiatric settings. Finally, questions for further research in this field are delineated. This Tobacco Reconceptualization in Psychiatry (TRIP) is long overdue, given the clear and compelling benefits of tobacco-free environments in psychiatric institutions.

Introduction

Since the rise of the cigarette at the beginning of the 20th century,1 there has been growing interest in the use of tobacco by persons with mental health and addictive (MHA) disorders. However, despite the increasing appreciation of the higher rates of tobacco smoking in MHA populations, there has been less success in smoking cessation and increased health risks of tobacco use in this subset of smokers compared to the general population. Moreover, there have been only scattered attempts to effect tobacco-free institutional treatment environments for these persons with mental health and addictions co-morbidity. This review is a critical attempt to bring together the tobacco treatment and policy literature, and make recommendations for the implementation of integrated treatment and regulatory environments in mental health and addictions settings such that the institutions that serve these clients can achieve a tobacco-free status. We hope that this consideration of a Tobacco Reconceptualization in Psychiatry (TRIP) will raise awareness of the scope of the tobacco problem in psychiatry, and practical ways that serve the best interests of our patients, such that we can address this most serious preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in our patients with co-morbid psychiatric illness.

Why is tobacco use and dependence problematic for people with mental illness?

Higher Rates of Tobacco Smoking

The prevalence of smoking among individuals with MHA disorders exceeds those in the general population by 2–4 fold.2–5 In patients with depressive and anxiety disorders, smoking rates range from 40 – 50%, and as high as 70–90% in patients with chronic schizophrenia.6,7 Individuals with MHA disorders account for a substantial proportion (up to 50%) of cigarettes sold in the United States, which is estimated to be approximately $180 billion in tobacco industry sales annually.8–11 In addition to high rates of smoking, those with MHA disorders tend to smoke more heavily, smoke for a greater number of years, and prefer the taste of higher tar cigarettes compared to smokers in the general population.2,12

Risk for Tobacco-Related Illness

Cigarette smoking is a significant public health problem due to the strong link between smoking and diseases. Tobacco is responsible for 3–5 million deaths yearly worldwide and this rate is expected to grow to 10 million per year between 2020 and 2030.2,13 Individuals with MHA disorders are at higher risk for many tobacco-related diseases when compared with the general population including cardiovascular illness, respiratory disease, and cancer.3,14,15 These tobacco-related illnesses have been suggested to be the leading cause of death among smokers with MHA disorders.4,14 Among individuals with schizophrenia, the majority of deaths, excluding suicide and accidents, are related to cigarette smoking.16 In fact, it has been estimated that schizophrenia and other serious and persistent mental illness (SPMIs) are associated with 20–25 years less life expectancy compared to the general population,4,5 and tobacco dependence is estimated to contribute to 12–13 years of this shortened life expectancy.17

Barriers to quitting

Smokers with MHA disorders have more trouble with smoking cessation than other smokers. Quit rates for alcohol use disorders (16.9%), bipolar disorder (25.9%), major depression (26.0%), and post-traumatic stress disorder (23.2%), are significantly lower than for smokers without MHA disorders (42.5%).3,10 Smokers with MHA disorders may find it difficult to quit because a range of psychosocial reasons such social and cognitive function impairments,18 high prevalence of smoking amongst peers and in supported housing environments, problems related to anxiety, boredom, loneliness, smoker’s identity, low motivation and/or low self-efficacy to make change, medication side-effects and lack of alternative coping resources. In addition, smokers with MHA disorders often do not have access to supports that help to promote quitting and sustained smoking abstinence.19

Considerable progress has been made in the treatment of tobacco use and dependence in smokers with co-morbid MHA illnesses. While there has been an increase in the efficacy of smoking cessation treatments with the development of tailored interventions for individuals with co-morbid tobacco use and MHA disorders, long-term smoking quit rates remain significantly lower than rates of smokers without mental illness. One barrier to smoking cessation treatment in persons with MHA disorders has been the misconception that successful smoking cessation will undermine MHA disorder treatment efforts, while at the same time removing a source of enjoyment for MHA patients. In actual fact, neither smoking reduction or abstinence adversely affect psychiatric functioning; in some cases it has been found to improve MHA symptoms.19

Explanations for Co-morbidity of Tobacco Dependence in PD and SUDs

Several explanations have been proposed for the high prevalence of tobacco dependence in people with MHA disorders.4 First, there may be intrinsic factors (e.g., shared genes) that predispose people with MHA disorders to initiation and maintenance of smoking behaviors. Second, nicotine may be used by MHA patients to self-medicate psychiatric symptoms and psychotropic drug side effects.20–22 Third, there may be common social and environmental determinants of this co-morbidity (e.g., easy access and availability, poverty, and stressful living situations). Not surprisingly, the co-occurring presentation of psychiatric and addictive disorders is strongly associated with cigarette smoking.3

Nicotine modulates several neurotransmitter systems that are involved in the pathogenesis of MHA, including dopamine (DA).22,23 The reinforcing effects of nicotine are mediated through activation of presynaptic nAChRs located on mesolimbic DA neurons.24,25 The role of mesolimbic DA neurons in mediating the reinforcing effects of nicotine is suggested by rodent studies demonstrating that lesions of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) reduce nicotine self-administration, as well as local infusions of the nAChR antagonist mecamylamine into the VTA.26,27 Nicotine promotes the release of other neurotransmitters including acetylcholine, endogenous opioid peptides, GABA, Glu, norepinephrine, and serotonin, which are also involved in the pathogenesis of MHA.25 These pre-clinical findings provide a heuristic link between the high prevalence of cigarette smoking and the pathophysiology underlying MHA disorders.

Should Mental Health and Addictions Treatment Facilities be Tobacco-Free?

Effects of Tobacco Bans

See Table 1 for a review of studies examining the outcomes of smoking bans on inpatient units. In addition to details about the type of ban, measures used to assess ban outcomes, and specific ban outcomes, each study was rated by two of the authors (TGM, AHW) and classified as follows: 1) positive outcomes, 2) mixed outcomes (or no change in outcome variables), or 3) negative outcomes. Overall, the literature on tobacco bans suggests that smoke-free units would be beneficial for both patients and staff. Although many staff members are skeptical of the ban initially, about one-third of the studies report that staff anticipated more problems than actually occurred.28–36 Overall, a tobacco ban does not significantly increase the occurrence of conflicts, violence, or disruptive events,33,35,37–40 and some studies even report a decrease in aggressive behavior.39,41 Moreover, for the majority of studies, there were no significant increases in the usage of as needed medications (e.g., PRNs).31,33,37,38,42 Although some studies do report problems including increased use of seclusion and restraint, high demands on staff, adjustment problems among patients,29 surreptitious smoking and staff conflicts,43 verbal assaults, and the increased use of PRN medications,44 many of these problems could be avoided if the ban is appropriately planned and is consistently enforced (see Section D), or if a full versus partial ban is implemented. A summary of the advantages and disadvantages of tobacco bans is presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Summary of Studies Describing Institutional Tobacco Bans in Mental Health and Addictions Facilities

| Type of Ban |

Summary of Smoking Ban Outcome |

Author (Year) |

Setting | Sample size of patients and staff |

Details of Smoking Ban |

Smoking Intervention Offered |

Methods Used to Assess Ban Outcomes |

Outcomes of the Smoking Ban |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Partial Ban |

1 | Anderson and Larrabee (2006)39 |

Psychiatric hospital, United States |

38 patients‡ | Permitted to smoke outside of the hospital. |

Smoking cessation education and NRT for patients. Education groups for staff. |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

Positive Outcomes: Decrease in anger and aggression, increase in patient satisfaction with areas of the program (support, order and organization, program clarity), staff and patients anticipated more problems than occurred. |

| 33 staff‡ | ||||||||

| 2 | Dingman et al. (1988)28 |

12-bed, acute inpatient locked unit at the University hospital, United States. |

60 patients, 73% smokers |

Permitted to smoke outside of the building. |

None reported. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

Positive Outcomes: Decrease in conflict over cigarettes, staff anticipated more problems than occurred. No Change: No significant changes in aggression, medication doses |

|

| 23 staff, 20% smokers | ||||||||

| 2 | Resnick and Bosworth (1989a)108 |

12-bed, acute inpatient unit at the University hospital, United States. |

165 patients completed a survey, 60 patient charts reviewed, 100% smokers |

Permitted to smoke outside of the building. |

NRT & education groups |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

No Change: No significant changes in medication doses, PRN medication, seclusion, restraints |

|

| 25 staff pre ban and 20 staff post ban‡ | ||||||||

| 2 | Thorward and Birnbaun (1989)42 |

17-bed, general psychiatry, acute care inpatient unit, United States. |

152 patients, ∼60% smokers |

Permitted to smoke outside of the hospital but during organized activities with unit staff. |

NRT | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

No Change: No significant changes in use of PRN medications, patients smoking behavior post- admission. Negative Outcomes: Violations of ban were significant. |

|

| § | ||||||||

| 2 | Smith and Grant (1989)30 |

42-bed, inpatient open unit, United States. |

32 patients, 41% smokers |

Permitted to smoke outside of the building. |

NRT, stress management, and staff education. |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

Positive Outcomes: Staff anticipated more problems than occurred Negative Outcomes: Many problems (e.g., verbal threats) decreased after the ban except for the 6th week post-ban. |

|

| 22 staff, 18% smokers | ||||||||

| 2 | Erwin and Biordi (1991)32 |

Two 21-bed acute open units, Veterans’ hospital, United States. |

§ | Permitted to smoke outside of the hospital. |

Education groups, stress management, and self-help materials provided. |

1, 2, 4 |

Positive Outcomes: 70–75% of the staff felt the ban was a success. |

|

| 29 staff‡ | ||||||||

| 2 | Cooke (1991)38 |

20-bed acute unit, Canada. |

§ | Permitted to smoke outside of the hospital. |

Education groups and self-help materials |

6, 7 |

Positive Outcomes: Several patients reduced amount of cigarettes smoked per day. No Change: No significant increase in aggressive behaviour, use of PRN medications |

|

| 2 | Parks and Devine (1993)34 |

41 state-operated extended care units in 17 states, United States. |

§ | Permitted to smoke outside of the hospital. |

NRT and clonodine patches. |

2, 6 |

Positive Outcomes: Staff anticipated more problems than occurred. No Change: 95% reported no change or decrease in violence and aggression; 98% reported no change in use of as-needed medication; 98% reported no change or decrease in use of seclusion or restraints. No change in sneaking cigarettes. |

|

| § | ||||||||

| 2 | Rauter et al. (1997)109 |

145-bed acute open unit, United States. |

∼128 patients’ per day - double check |

Locked ward inpatients escorted to smoke outside of the hospital, and free access for those permitted to leave the ward. |

NRT, educations groups and staff education. |

1, 2, 3 |

Positive Outcomes: Patient’s complaints decreased post-ban. No Change: No increase in assaults, incidents of contraband post- ban |

|

| § | ||||||||

| 2 | Etter and Etter (2007)110 |

Two inpatient psychiatric units; an admission unit (16 beds) and a medium-stay unit (16 beds), Switzerland |

103 patients, ∼70% smokers |

Smoking was banned inside, other than two dedicated smoking rooms in each unit. Permitted to smoke outside of the hospital. |

NRT and education booklets. Staff trained to treat tobacco dependence. |

1, 2, 4, 5 |

Positive Outcomes: Partial smoking ban was accepted by both patients and staff. No Change: No change in TSE, conflicts |

|

| 111 staff ∼26% smokers | ||||||||

| 2 | Etter, Khan, and Etter (2008)†54 |

Two inpatient psychiatric units; an admission unit (16 beds) and a medium-stay unit (16 beds), Switzerland |

49–77 patients at each of 4 time points ‡ |

First a partial ban of indoor smoking (Etter and Etter, 2007). Then a ban of all smoking inside the building (smoking still permitted outside of the hospital). |

NRT and education booklets. Staff trained to treat tobacco dependence. |

1, 2, 4, 5 |

Positive Outcomes: Smoking cessation rates increased compared to the partial ban. No Change: No change in TSE, Conflicts |

|

| 53–57 staff at each of 4 time points ‡ | ||||||||

| 3 | Richardson (1994)111 |

Acute open unit, United States. |

§ | Permitted to smoke outside of the hospital |

NRT, staff and patient education groups. |

2, 8 |

Negative Outcomes: Conflict over smoking escort privileges, inconsistent limit setting. Note: Problems decreased once staff demonstrated uniform commitment to the ban. |

|

| § | ||||||||

| 3 | Greeman and McClellan (1991)29 |

60-bed acute open unit Veterans’ hospital, United States. |

1796 patients, more than 50% were smokers |

Permitted to smoke outside of the hospital. Total ban for inpatients. |

NRT & education groups. |

Not reported |

Positive Outcomes: Staff anticipated more problems than occurred Negative Outcomes: Problems arose in 20–25% of patients: Increased use of seclusion and demands on staff, adjustment problems among patients (even two years after the ban). |

|

| § | ||||||||

| 3 | Hoffman and Eryavec (1992)43 |

18-bed acute open unit, Canada. |

§ | Permitted to smoke outside of the hospital and passes handed out to leave the hospital to smoke. |

NRT, patient and staff education. |

2, 8 |

Positive Outcomes: Patients reported the ban prevented them from relapsing to smoking once admitted to the hospital. Negative Outcomes: Problems due to inconsistency resulted in surreptitious smoking and staff conflicts. |

|

| § | ||||||||

|

Total Ban |

1 | Quinn et al. (2000)41 |

190-bed acute unit, United States. |

∼190 patients per day pre ban, ∼188 patients per day post-ban‡ |

Smoking prohibited for all patients. |

NRT and education groups. |

1, 2, 3 |

Positive Outcomes: Significant decrease in verbal acts of aggression, physical acts of aggression. Staff anticipated more problems than occurred. |

| § | ||||||||

| 1 | Hempel et al. (2002)63 |

Maximum security psychiatric hospital, United States |

140 patients, 79% smokers |

Smoking prohibited for all patients. |

NRT and education groups. |

1, 2, 3 |

Positive Outcomes: Decreases in disruptive behaviors and sick call in moderate and heavy smokers, Staff anticipated more problems than occurred. |

|

| § | ||||||||

| 2 | Beemer (1993)31 |

Open psychiatric unit of hospital, Canada. |

§ | Smoking prohibited for all patients. |

NRT and clonodine patches. |

1, 2, 8 |

Positive Outcomes: Less problems than anticipated by staff, even improvements were noted in workplace conditions. No Change: No significant increase in use of PRN medications or physical restraints |

|

| § | ||||||||

| 2 | Taylor et al. (1993)112 |

Two 26-bed locked units of 934-bed g general hospital, United States. |

232 patients, 37% smokers |

Smoking prohibited for all patients. |

NRT and hard candies. |

1, 2, 3, 4 |

No Change: No significant increase in disruptive events or smoking behavior post ban |

|

| 50 staff ‡ | ||||||||

| 2 | Patten et al. (1995)113 |

28-bed locked unit, United States. |

362 patients (184 patients pre-ban, 178 patients post- ban), 36.7% smokers |

Smoking prohibited for all patients. |

NRT, staff and patient education groups. |

1, 2, 3, 4 | Positive Outcome: Decrease in use of seclusion No Change: No change in medication use or use of restraints Negative Increase in smoking in room, nursing assistance |

|

| 126 staff, 7% smokers | ||||||||

| 2 | Haller et al. (1996)33 |

16-bed locked unit, United States). |

114 patients (21 patients pre-ban and 93 patients post-ban)‡ |

Smoking prohibited for all patients. |

NRT, educational materials, and staff education. |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | Positive Outcome: Staff anticipated more problems than occurred. No change: No significant increase in disruptive events/conflicts, use of PRN medications |

|

| 120 staff (67 staff pre-ban pre and 53 post-ban)‡ | ||||||||

| 2 | Velasco et al. (1996)*37 |

25-bed locked psychiatry unit, United States |

194 patients from Ryabik et al., 1995 plus 96 patients at 2 year follow- up‡ |

Smoking prohibited for all patients. |

NRT | 1, 2, 3 |

No change: No significant increase (2 years post-ban) in verbal assaults, use of PRN medications Negative Outcomes: Significant increase in use of soft restraints |

|

| § | ||||||||

| 2 | Matthews et al. (2005)35 |

18-bed acute crisis stabilization unit for men, United States. |

3000 patients in the psychiatric hospital‡ |

Smoking prohibited for all patients. |

NRT and education. |

1, 2, 3, 4 |

Positive Outcomes: Staff anticipated more problems than occurred. No Change: No significant changes in physical restraints or seclusions, episodes of assault or self-harm, incidence of contraband |

|

| 24 staff‡ | ||||||||

| 2 | Harris et al. (2007)36 |

296-bed diverse psychiatric facility, Canada |

119 patients‡ | Smoking prohibited for all patients. |

Not reported. | 2, 3 |

Positive Outcomes: Staff anticipated more problems than occurred. No Change: No change in psychiatric symptomatology, overall psychological well-being. Negative Outcomes: Increase in patient and staff physical aggression (returned to normal 1 year post-ban). |

|

| § | ||||||||

| 2 | Ryabik et al. (1995)44 |

25-bed locked psychiatry unit, United States. |

194 patients‡ | Smoking prohibited for all patients. |

NRT | 1, 2, 3 |

No change: No changes in security calls, seclusion, restraints, assaults Negative Outcomes: Significant increase in verbal assaults (1st week post-ban only), use of PRN medications for agitation |

|

| § | ||||||||

| 3 | Bronaugh and Frances (1990)114 |

Acute inpatient university hospital unit, United States. |

94 patients, 62% smokers |

Smoking prohibited for all patients. |

None reported. | 2, 3, 7 |

Negative Outcomes: Problems reported of patients’ secretly smoking, increased patient-staff tension. Patients with high levels of addiction were least compliant with smoke-free policy. |

|

| § |

Abbreviations: NRT, nicotine replacement therapy; PRN, as needed medications; TSE, environmental tobacco smoke exposure

Two-year follow-up to Ryabik et al. (1995)

Follow-up to Etter and Etter (2007)

% of smokers not reported

Sample size of patients and/or staff not reported

Rating Categories for “Summary of Smoking Ban Outcome”:

1=Positive outcomes

2=Mixed outcomes (positive and minor negative outcomes) or no change in outcomes

3=Negative outcomes

Rating Categories for “Methods Used to Assess Ban Outcomes”:

1=Pre-Ban Assessment

2=Post-Ban Assessment

3=Review of Records

4=Survey of Staff

5=Survey of Patients

6=Interviews with Staff

7=Interviews with Patients

8=Observations of authors

Table 2.

The Advantages and Disadvantages of Tobacco Bans in Psychiatric and Addiction Treatment Facilities

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Excellent opportunity to provide motivational interventions for those not initially motivated to attempt smoking cessation. |

Low inpatient interest in quitting. This is low on their hierarchy of needs. |

| Effects of interventions can be monitored in a controlled therapeutic setting by staff and physicians. |

Staff and administration are often reluctant as they may perceive this to be a distraction to treatment plan and a critical “positive” reinforcer. This is more often the case for staff and administration who are themselves smokers. |

| Reduction in episode of seclusion and restraint, PRN use and decreased length of stay. |

Lack of training of unit staff or other qualified people to conduct smoking cessation counseling. |

| Smoke-free work environment goals are promoted, and consistent with wellness interventions that being implemented in most inpatient settings. |

Unmotivated inpatients pose a barrier to success of any patients who are motivated to quit. |

Ethics of Tobacco Bans – The Client Rights Issue

The question has been raised of whether it is a violation of patients’ rights for institutions to prohibit smoking in an effort to promote and protect the health and safety of smoking and nonsmoking patients (and staff). Although there is little legal precedent in favor of tobacco smoking as a right instead of a privilege, this question continues to be debated in several state courts in the United States through lawsuits raised by patients or patient advocacy groups attempting to prevent restrictions on smoking at treatment facilities.45 It has been argued that patients make a free and informed choice to smoke, fully aware of the harms of smoking, and some staff view smoking as an insignificant problem in comparison to the immediate problems faced by these patients and therefore condone smoking behaviors. Others feel that treatment for acute symptoms of MHA disorders should outweigh long-term wellness plans that may include tobacco cessation46 or report concerns about an increase in negative patient behaviors when bans are put into effect (see Obstacles to Implementing Tobacco-Free Psychiatric Facilities Section).

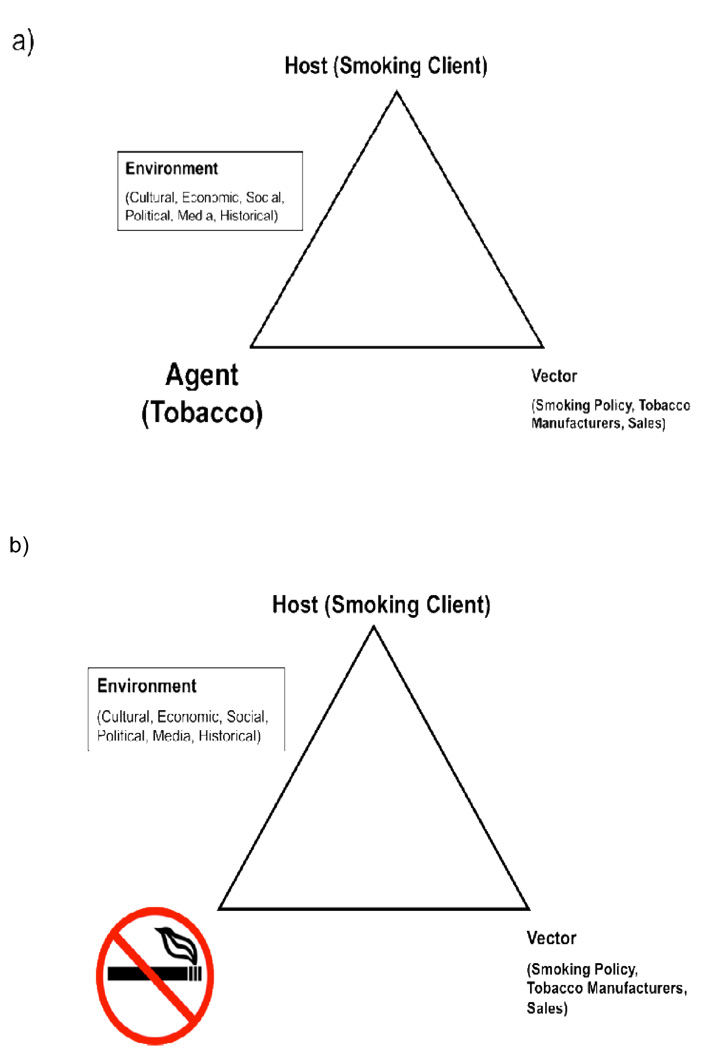

However, nicotine is a highly addictive substance25,47 with severe health consequences for these adults.3,4,14,15 Allowing patients to smoke is harmful to their health and undermines their treatment, especially treatment of substance dependence. Smoking in psychiatric hospitals are restricted to a small, set number of smoke breaks that are managed by staff which may have negative consequences for both patients and staff.45 For example, patients who are limited to fewer cigarettes then they smoke on a regular basis may experience significant and persistent nicotine withdrawal. Staff must spent a significant amount of time distributing and gathering smoking materials before and after each smoke break and supervising breaks during which they are exposed to the dangers of second-hand smoke. It is further argued that once admitted to a hospital, all patients should be required to follow institutional rules, schedules, and restrictions (e.g., medications, sleep schedules, and freedom) and that restricting smoking is a necessary part of a hospital’s mission statement to enhance the health of their patients and staff. Figure 1 illustrates the Public Health model as applied to tobacco in psychiatric facilities (Fig.1a), with the ultimate goal being the restriction of tobacco from the institution (Fig.1b).

Figure 1. Tobacco Control – Public Health Model for Mental Health and Addictions Settings.

Panel A – The Agent/Host/Vector Model Applied to Tobacco use; Panel B – Annotated with the Goal of Banning Tobacco from Institutions.

Obstacles to Implementing Tobacco-Free Psychiatric Facilities

Although numerous mental health and addiction facilities have attempted to restrict or ban the use of tobacco products on their property, various obstacles, related to or in addition to the question of clients’ rights, have been faced during this process.48 First, smoking is perceived to be part of the culture in these settings,2 and change is faced with resistance from patients and their families, staff, and physicians as some support the patients right to choose.48,49 Second, some staff and psychiatrists may feel that the advantages of smoking outweigh the disadvantages, as smoking provides social and psychiatric benefits (facilitates socializations, reduces boredom, medication side effects3) and is used as part of the “token economy.”48 With the recent push to implement tobacco bans in public buildings, excepting these chronic institutional treatment settings (nursing homes, psychiatric hospitals, and drug treatment facilities) may send a mixed message, and perpetuate a “double stigma” since these patients are already victims of stigma because of a mental illness and/or addiction.48 Both institutions and governments need to acknowledge the risks of tobacco dependence/addictions in MHA populations,48 and that ultimately tobacco bans would be beneficial for the health and well-being of these highly vulnerable patients and their non-smoking peers.

A significant obstacle to implementing the ban is concern about the potential of negative behavioral responses from patients. A common fear among staff is that patients would not cope well with a ban; however, the literature (see Table 1) suggests that there is little evidence for an increase in aggression, increased use of restraints, discharge against medical advice, or use of as-needed medications.2,50 One study has found that episodes of physical and verbal aggression actually decreased after the tobacco ban was implemented.41 Generally, staff members tend to anticipate more problems than actually occurred,2 demonstrating that the ban will not negatively affect the patient’s behavior, and should be seen as an obstacle to implementing a tobacco ban.

Many studies have suggested that staff members (often nurses) feel that smoking plays a therapeutic role,51,52 as some nurses and other allied health professionals smoke cigarettes with the patients in order to establish a therapeutic relationship with them.53 This could be viewed as another obstacle, as staff may fear they will not be able to develop a relationship with patients if smoking is prohibited. However, Etter and colleagues54 demonstrated that a smoking ban did not harm the staff-patient relationship. Staff should not rely on cigarettes to in order to facilitate a therapeutic relationship with patients, especially given the health risks engendered by tobacco use (another mixed message).

Another obstacle is motivating patients and staff to support a tobacco ban. If patients were enthusiastic about quitting smoking, and staff encouraged this behavior change, the process of instituting a tobacco ban would proceed more smoothly. When staff and administration are resistant to the idea of a tobacco ban, this tends to undercut the process of implementation. This may be especially true amongst staff and administration that are smokers themselves. Importantly, one recent survey found that smoking staff were significantly less likely to identify tobacco use as a problem and initiate referrals to tobacco treatment as compared to non-smoking staff; quitting smoking by staff was found to be associated with a level of identification and referral related to tobacco use at rates comparable to non-smoking staff.55 Smoking staff are also affected by the rules instituted by the ban and may be resistant toward changing their behavior although some studies have found decreases in staff smoking rates after bans as staff members use this opportunity to quit smoking.2 There may also be a lack of trained unit staff or other qualified people to conduct smoking cessation counseling and support, a critical ingredient to supporting a successful ban. Finally, implementing a ban will require additional funding, as money will be required to hire and train staff, as well as pay for pharmacological agents for treatment such as nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs). Although there are some obstacles to a tobacco ban, all change comes at a cost, but with the appropriate investment of financial resources and staff training, this change could have significant long-term health benefits for both smoking and non-smoking patients and staff.

In addition to the obstacles already mentioned, the use of contraband cigarettes in psychiatric and addiction treatment facilities is another barrier. In an effort to control tobacco use, the government has raised the price of tobacco products by increasing the taxes. Unfortunately, this has resulted in an increase in the availability of contraband cigarettes, which are sold at a discounted rate in comparison to legal cigarettes.56 Cheap contraband cigarettes may diminish motivation for smoking cessation57 and increase rates of relapse.58 Callaghan and colleagues59 investigated the use of contraband cigarettes among patients at a psychiatric hospital and found that 54% of cigarettes smoked by chronic psychiatric patients in Toronto, Canada were unbranded (contraband) cigarettes. The proclivity to the initiation and maintenance of tobacco dependence among those with serious mental illness, the low cost of contraband cigarettes and the high availability of these tobacco products (which are unregulated insofar as tar and toxin content) may explain the high rates of use of contraband cigarettes in psychiatric and addictions treatment facilities.

Can we achieve tobacco-free institutional settings, and how should we do this?

Type of Tobacco Bans

In order to implement a tobacco-free hospital setting, administrators in mental health and addictions treatment facilities must decide on what type of ban to implement. The options include a full ban, in which no smoking is permitted on units and the grounds of the hospital, or partial bans which designate certain areas and/or times when smoking is permitted. Although a partial ban may seem more attractive because of its less restrictive nature, partial bans can lead to patients trying to negotiate their cigarette smoking privileges with staff, which can result in an increased perceived value of cigarettes in the hospital setting.60 While some examples of complaints and verbal aggression have been associated with both partial and full bans, inconsistent enforcement of bans are a more common problems with partial bans,61 may lead to negative outcomes that could otherwise be avoided by the implementation of a full ban.61,62 In their review of twenty-six international studies reporting the effectiveness of smoking bans in psychiatric settings, Lawn and Pols2 concluded that inconsistent applications of bans across patient populations resulted in more damage and disruption for those hospitals that implemented partial bans as compared to full bans.

A full ban promotes consistency, as there is no confusion involved with this type of ban (“no ifs, ands or butts”; see Table 3). Several studies have suggested that although staff, patients, and visitors may initially oppose a total tobacco ban, their attitudes changed to favor a smoke-free environment following the implementation of the ban.2,50,63 These findings suggest that implementing a total ban for all tobacco products provides the most positive results in a psychiatric setting. Therefore, this approach should be the long-term goal of all tobacco-free initiatives, with the caveat that implementation of partial bans may be used as a transitional step towards achievement of complete tobacco bans.

Table 3.

Evidence-Based Guidelines for Successful Implementation of Tobacco Bans in Inpatient Psychiatric and Addictions Treatment Settings

| Strict enforcement of the total smoking ban – no smoking can be tolerated (“no ifs, and or butts”!) |

| Staff and physicians need adequate training to deal with the consequences of the smoking ban. |

| To enforce a tobacco-free environment, patients need to be provided with behavioral support and pharmacotherapies (to manage tobacco withdrawal and cravings on the unit). |

| Encourage patients to maintain tobacco-free status once they are discharged – develop outpatient tobacco treatment plans. |

The New Token Economy: Increasing On-Unit Activities

Traditionally, psychiatric facilities have inadvertently promoted tobacco use, by deploying cigarettes as a means to modify behavior through the use of token economies.53,64 Token economies can facilitate clients to learn and perform desired behaviors. These types of economies have been explained as treatment delivery systems and as a means of providing learning principles in an attempt to focus on particular problems. LePage65 demonstrated that token economies may decrease the number of staff and patient injuries, and the improved safety environment allows staff members to focus their attention on treatment, rather than creating a dynamic of conflict which is ultimately counterproductive.

Since token economies are a useful means of modifying potentially disruptive behavior in a psychiatric setting, it might be reasoned that it would be beneficial to keep these economies in use. However, if a tobacco ban is implemented, administrators can introduce incentives other than cigarettes to motivate patients to follow the rules implemented on the ward and to reward good behavior. Such incentives could include privileges to leave the premises, movies, television, healthy food, internet and phone access, or increased visitors time, and other positive reinforcement approaches (e.g., draws for prizes of value once compliance with tobacco-free regulations are demonstrated). This would allow staff to use positive reinforcement techniques to modify disruptive and unwanted patient behaviors, without providing them with a harmful substance such as tobacco.

Patients in psychiatric hospitals may find themselves with extra time, and little activities to occupy this time, which can lead to boredom. Cigarette smoking provides an opportunity to temporarily leave the ward and facilitates socialization for psychiatric patients.66 Non-smokers are at risk for initiating cigarette smoking if admitted into a psychiatric ward where smoking is permitted, as a result of peer-pressure and boredom.6 When tobacco bans are put into place, the concern is that they may prevent the patients from connecting with one another, and increase boredom and inactivity. In fact, most studies (see Table 1) suggest that the opposite occurs.

In an effort to decrease boredom and enhance other means of socialization, increased ward activities (programming) may offer the most viable solution. These activities could include entertainment options, such as books, television and movies, or providing access to the internet. In an effort to increase socialization, ward outings to local museums, parks, and the community would provide a change of scenery that could promote communication among the patients. Educational courses are another alternative to keeping the patients occupied, while at the same time stimulating their minds. Lastly, providing the patients with physical activities, such as sports and exercise classes may promote socialization, and a healthy lifestyle. All of these various activities can provide the patients with an alternative to smoking, and could be used a part of the token economy, as these activities could be considered privileges and offer a healthy option to cigarettes as the token economy item.

Consistency (“No ifs, ands or Butts”)

Although a total tobacco ban is the ultimate goal, in order to align values, policies and changes in clinical practice it may sometimes be beneficial to work with both advocacy and policy stakeholders in the treatment settings. For example, in a hospital with a deeply entrenched pro-tobacco culture, a multi-pronged approach emphasizing policy, advocacy, staff training and program development is needed to produce the required change management to implement such bans. To this end, it is imperative that the rules are strictly and consistently enforced across the board. This consistency approach must be followed at all levels of staff, ranging from management to clinical staff support.2,61 In the review by Lawn and Pols,1 one of their key findings to a successful ban was consistency, coordination, and full administrative support. One hospital that noted an increase in problems following the implementation of the ban, including aggression, discharge against medical advice or increased use of medication, may have been a result of the lack of the administrative process to provide consistent enforcement of the ban.29 The staff in this hospital did not comply with the ban, as unauthorized patients were permitted access to cigarettes.63 It is necessary for staff to comply with and enforce the tobacco ban, and failure to so will result in negative consequences.

Provision of Pharmacotherapies

Educating the patients on, and providing them with, pharmacotherapies is essential in helping them refrain from smoking. These include NRTs (e.g., transdermal nicotine patch (TNP), gum, spray, inhaler, and lozenge), sustained-release bupropion (Zyban®), and varenicline (Chantix® in USA; Champix® in Canada and Europe), which have all been found to increase likelihood of quitting in psychiatric populations.19,67 All these therapies are convenient for nurses to distribute to inpatients with other daily (psychotropic) medications (with bupropion SR and varenicline needing a prescription).

Prophylactic NRT is recommended for inpatient in psychiatric and addictions settings, as it may reduce rates of discharge against medical advice where smoking is forbidden.6,68 TNP may be the best option because it is only administered once a day which may increase compliance.69 In addition, TNP delivers a fixed dose of nicotine continuously,70 which provides partial replacement of plasma nicotine levels6 and can target the acute nicotine withdrawal syndrome,19,71 a frequent determinant of smoking relapse.23,72

Sustained-release bupropion SR is a weak catecholamine reuptake inhibitor and non-competitive ion channel site antagonist at the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR),73 which has been proven to be an effective medication for smoking cessation in psychiatric population,73 especially if used in conjunction with behavioural therapy.74,75 Bupropion is currently the best studied treatment option for tobacco cessation in smokers with MHA disorders.40,73,74,76,77

Varenicline, an α4β2 nAChR partial agonist, has recently been added to the USPHS guidelines as a recommended first-line therapy19 and has also been shown to be a highly effective smoking cessation aid;76,78 comparative studies with bupropion SR have shown its superiority to this agent and placebo.79,80 While the typical side effects of varenicline are nausea and insomnia, severe adverse events have been reported, which include treatment-emergent psychosis, mania, impulsivity, agitation and suicidality.19 Physicians are advised to monitor their patients taking varenicline on a regular basis for the emergence of such neuropsychiatric symptoms.81 There are several on-going studies examining the safety and efficacy of varenicline in psychiatric smokers.19 Treatment with NRT, varenicline, and bupropion SR, are all possible strategies to alleviate the withdrawal symptoms commonly associated with smoking cessation once a ban is implemented, and such early treatment promotes self-efficacy in tobacco cessation efforts.19

Provision of Behavioral Support

While pharmacotherapies target the neurochemistry of tobacco addiction, concurrent behavioral support is required in order to teach coping strategies which can optimize cessation outcomes during the implementation of the ban, and increase the likelihood of long-term smoking cessation. Behavioral support can come in the form of self-help programs (increase motivation and improve readiness to quit, manage withdrawal symptoms, and preventative relapse measures),19 cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT),40,82–84 contingency management (CM),85,86 and motivational interviewing (MI).87 It has been suggested that the estimated four hours per day it takes staff to provide cigarettes, should be reallocated to the delivery of cessation counseling services.6,68

MI is a standard behavioral treatment that can be utilized successfully in smokers with co-morbid mental illness.88 MI would be beneficial for this specific population, as their low readiness to quit may be a significant barrier to smoking cessation.19 While MI has demonstrated that it is an effective smoking cessation treatment,73,87,89 it may also influence smoking treatment-seeking behavior.19,88 In light of these findings, MI should be frequently employed to encourage smoking reduction and cessation in psychiatric and addiction hospitals.88,90

CBT should be delivered by a trained clinician, as opposed to staff member trying to incorporate the therapy into his or her regular duties.91 CBT involves individual and/or group counseling, and can range in length from brief (10 – 15 minutes) to intensive (50 – 60 minutes), conducted once to several times per week. CBT has been demonstrated to be an effective behavioral therapy for smoking cessation, as a strong positive correlation exists between amount of counseling and smoking abstinence.92 CBT has been modified for smoking cessation in individuals with co-morbid mental illness,7,87,93 and would have suitable applications in a psychiatric hospital.

CM is an alternative behavioral intervention that could be applied when implementing a smoking ban. The goal of CM is to utilize reinforcement procedures systematically in order to modify smoking behaviors in a positive and supportive manner.94 This treatment has been found to reduce smoking,86,95–97 but must be used with caution as smoking relapse is high once the contingencies are withdrawn.19 CM can be applied when the ban is initially implemented, but other treatments must be employed in order to maintain smoking cessation (e.g. CBT and relapse-prevention skills).

Monitoring of psychotropic medications during inpatient and outpatient treatment

Cigarette smoking can decrease the blood concentrations of several psychiatric medications.98–101 This is an important consideration when prohibiting cigarette smoking within psychiatric hospitals. Smoking increases hepatic enzyme activity (primarily the CYP 1A2 and, to a lesser extent the 3A4 isoenzyme systems), which accelerates the metabolism of psychiatric medications,99–101 and can lower plasma psychotropic drug concentrations.50 Examples of psychotropic medication affected in this manner include clozapine, haloperidol, olanzapine, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), valproate and caffeine.4 As a result of this smoking interaction with psychiatric medication, patients who smoke tend to take considerably higher doses of antipsychotic drugs.50,99–102 This effect is the result of the tar in cigarettes, rather than the nicotine itself.50,102

A tobacco ban may have significant implications for patients taking antipsychotics once they alter their smoking habits on the ward, or after they are discharged.6 There have been several reports of adverse reactions as a result of high concentrations of clozapine or olanzapine following smoking cessation.103,104 As a result, a stepwise daily dose reduction of about 10% until the fourth day since the last cigarette is recommended, in combination with therapeutic drug monitoring since each patient will react differently to smoking abstinence.6,105 In order to prevent problems, it is imperative to adjust the patient’s medication dosage accordingly and monitor them, in order to ensure these medications are working. Also, if these patients begin smoking after discharge, their medication dosage should be adjusted accordingly so continued monitoring of smoking status and medication response is extremely important.

Provision of Outpatient Services

While psychiatric wards with a tobacco ban provide an opportunity to initiate smoking cessation because of the policies directed against smoking and the increased awareness and availability of medications and behavioral therapies, most programs at this time focus on smoking cessation during hospitalization with less emphasis on long-term abstinence. In order to increase long-term smoking cessation success among psychiatric patients, it is imperative to work with patients while they are hospitalized and to monitor and treat these patients when they return back to the community. The risk of relapse is high; Olivier and colleagues6 have reported that the majority of patients return to smoking within five weeks of discharge. During hospitalization, staff can work with patients on enhancing motivation for long-term abstinence, developing skills to deal with triggers, cravings, and stress after release from the hospital, and examining benefits of not smoking that are experienced while in psychiatric units (e.g., more money, an easier time breathing). In order to prevent tobacco use relapse after release, improvements must be made both in discharge planning and linking clients to appropriate outpatient community resources so that adequate treatment support is continued post-discharge.6 Support should involve regular outpatient follow-up smoking cessation/relapse-prevention sessions and standard pharmacotherapy (e.g. NRT, bupropion SR, varenicline) of both brief and extended treatment based on the clinical situation.19 Thus, if the patients are sufficiently monitored after hospital discharge, the high rates of tobacco relapse associated with inpatient discharge in mental health and addictions treatment settings could be reduced.

Recommendations and Conclusions

This call to action is a dramatic cultural shift in institutional attitudes, policy, and practice considering the fact that historically psychiatric and addiction treatment facilities in the North America have, to varying degrees, been buying, dispensing, and facilitating tobacco consumption for their patients. Often this practice has been justified and related to in terms of cultural norms, therapeutic effectiveness, and/or clients’ rights. However, the consumption of tobacco products as an everyday clinical practice in psychiatric institutions must transcend this dominant ideology and take a progressive leap of faith to create mental health and addiction treatment environments structured on the concept of wellness and recovery, so that the health and well-being of patients is the foremost priority.

The achievement of tobacco-free inpatient and outpatient treatment environments in psychiatric and addictions facilities is clearly a noble goal (Figure 1), for which this review documents clear and beneficial outcomes for patients, staff and institutions. Based on our review and discussion, the following conclusions and recommendations can be made:

Tobacco-free mental health and addictions settings can be achieved by an integration of policy and treatment measures, which have the goals of promoting a healthy workplace and tobacco cessation for all patients and staff.

During the institution of tobacco-free environments in MHA treatment settings, the rights of smokers should be respected, but at the same time the rights of non-smoking clients and staff need to be promoted. The process of taking an institution tobacco-free needs to be well-considered by the senior management of an institution, which must take the lead in promoting the goals and objectives of the smoke-free environment to the hospital staff, patients and their families (e.g. the “top down” management approach). The key to success is a clear communication strategy and extensive preparatory efforts prior to initiating the smoke-free hospital grounds, with the initial goal of achieving staff and patient buy-in to the process.

In service of creating tobacco-free grounds, a “bottom up” process should be developed for staff, patients and families to ensure a transparent process where the views and concerns of all parties are heard, discussed and debated. Ultimately, senior leadership is responsible for the success of the process, and needs to take ownership for the successes (and failures) of the implementation strategy. The identification and promotion of staff “champions” for the tobacco ban needs to be initiated early on in the process as these individuals can provide support and facilitate education, training, and tobacco change program development for staff peers, and educational efforts to ultimately support the ban. Further, concerns from staff members who are smokers should be addressed and smoking cessation support and services should be offered to staff members who are interested in quitting.

A critical determinant of the process is the requirement that staff receiving training on how to initiate and enforce tobacco-free psychiatric inpatient units and outpatient programs, through the development (prior to the tobacco ban) of unit programming geared to psychoeducation on the risks of continued smoking, and support for smoking cessation programs for both patients and staff. There should be an initial emphasis on increasing the skills of staff in motivational interviewing, given that engagement and persuasion of the MHA smoker is paramount. The involvement and support of hospital security services is critical to the enforcement aspect of tobacco bans.

Physicians (including psychiatrists) and nurses need continuing education and support by senior leadership on the importance of identifying tobacco use,106,107 and on the state of the art implementation of integrated behavioral and pharmacological treatments.

-

Further research on the safety and process of initiating and maintaining tobacco-free inpatient and outpatient settings is necessary, especially in terms of understanding the impact on psychiatric and addiction outcomes (e.g. risk of exacerbation or relapse of the co-morbid MHA condition in patients admitted to smoke-free versus smoking units), and effects of such smoking bans on the achievement of short- and long-term cessation and reduction outcomes. Moreover, the systematic study of such bans on quality of care and administrative health outcomes (e.g., frequency and duration of seclusion and restraint, episodes of agitation and violence, PRN psychotropic medication use, frequency of elopement and against medical advice (AMA) discharge) using prospective designs is warranted, as are the study of patient, staff, and institutional variables associated with more and less successful ban implementation (e.g., length of preparation time and education, duration of hospital stay (acute versus longer term), type of alternative reinforcers and activities provided). Finally, research is needed examining the cost-effectiveness and quality of life impact of tobacco-free policy changes in psychiatric hospitals.

Accordingly, there is much work that needs to be done before we can make the wide dissemination of tobacco-free treatment settings in mental health and addictions facilities a reality. Nonetheless, this Tobacco Reconceptualization in Psychiatry (TRIP) provides a theoretical and practical framework for achieving these important goals. We can make this a “good” TRIP or a “bad” TRIP – the choice is ours!

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants R01-DA-15757, R01-DA-13672 and K02-DA-16611 (Dr. George) and K12-DA-000167 (Dr. Weinberger) from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, Md; a Young Investigator Award from NARSAD, Great Neck, NY (Dr. Weinberger); a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (Dr. George); and the Endowed Chair in Addiction Psychiatry at the University of Toronto (Dr. George).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests:

Dr. Weinberger reports grant support from Sepracor, Inc., the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Dr. Selby reports grant support from Health Canada, the Canadian Institutes on Health Research (CIHR), Canadian Tobacco Control Research Initiative (CTCRI), the Ontario Ministry of Health, Smoke Free Ontario (SFO), Alberta Health Services (formerly Alberta Cancer Board), Vancouver Coastal Authority and Pfizer, Inc., and consulting income in the past two years from Johnson & Johnson Consumer Health Care Canada, Pfizer Inc. Canada, Pfizer Global, Sanofi-Synthelabo Canada, GSK Canada, Genpharm, Prempharm, Evolution Health Systems Inc.(V-CC Systems Inc.) and eHealth Behaviour Change Software Co. Dr. George reports grant support from NIDA, NARSAD, CIHR, the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), CTCRI, Pfizer, Inc. and Sepracor, Inc., and consulting income in the past two years from Pfizer, Janssen-Ortho International, Astra-Zeneca, GenPharm, Prempharm, Eli Lilly, Memory Pharmaceuticals, CME LLC, the Calgary Health Region, the National Institutes of Health, the University of Manchester (Australia), the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP) of the State of California and the Donaghue Medical Research Foundation, West Hartford, Conn.. Taryn Moss, Jennifer Vessicchio, Vincenza Mancuso, Sandra Cushing, Michael Pett, and Kate Kitchen have no disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Brandt AM. The Cigarette Century. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawn S, Pols R. Smoking bans in psychiatric inpatient settings? A review of the research. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:866–885. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalman D, Morissette SB, George TP. Co-morbidity of smoking in patients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Addict. 2005;14:106–123. doi: 10.1080/10550490590924728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morisano D, Bacher I, Audrain-McGovern J, George TP. Mechanisms underlying the co-morbidity of tobacco use in mental health and addictive disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:356–367. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, et al. Tobacco use cessation in psychiatric disorders: National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Report. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1691–1715. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olivier D, Lubman DI, Fraser R. Tobacco smoking within psychiatric inpatient settings: biopsychosocial perspective. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41:572–580. doi: 10.1080/00048670701392809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziedonis D, George TP. Schizophrenia and nicotine use: report of a pilot smoking cessation program and review of neurobiological and clinical issues. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23:247–254. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Federal Trade Commission. Federal trade commission cigarette report for 2003. Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, Stinson FS, Dawson DA. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1107–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prochaska JJ, Hall SM, Bero LA. Tobacco use among individuals with schizophrenia: what role has the tobacco industry played? Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:555–567. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goff DC, Henderson DC, Amico E. Cigarette smoking in schizophrenia: relationship to psychopathology and medication side effects. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1189–1194. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Guidelines for controlling and monitoring the tobacco epidemic. Geneva: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, et al. Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment. Role of tobacco use in a community-based cohort. JAMA. 1996;275:1097–1103. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.14.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lichtermann D, Ekelund J, Pukkala E, Tanskanen A, Lonnqvist J. Incidence of cancer among persons with schizophrenia and their relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:573–578. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212–217. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.3.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziedonis DM, Zammarelli L, Seward G, et al. Addressing tobacco use through organizational change: a case study of an addiction treatment organization. J Psychoact Drugs. 2007;39:451–459. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McChargue DE, Gulliver SB, Hitsman B. Would smokers with schizophrenia benefit from a more flexible approach to smoking treatment? Addiction. 2002;97:785–793. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hitsman B, Moss TG, Montoya ID, George TP. Treatment of tobacco dependence in mental health and addictive disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:368–378. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalman D, Kahler CW, Tirch D, Kaschb C, Penk W, Monti PM. Twelve-week outcomes from an investigation of high-dose nicotine patch therapy for heavy smokers with a past history of alcohol dependence. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:78–82. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sacco KA, Bannon KL, George TP. Nicotinic receptor mechanisms and cognition in normal states and neuropsychiatric disorders. J Psychopharmacol. 2004;18:457–474. doi: 10.1177/0269881104047273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalack GW, Healy DJ, Meador-Woodruff JH. Nicotine dependence in schizophrenia: clinical phenomena and laboratory findings. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1490–1501. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.George TP, O'Malley SS. Current pharmacological treatments for nicotine dependence. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke PB, Fu DS, Jakubovic A, Fibiger HC. Evidence that mesolimbic dopaminergic activation underlies the locomotor stimulant action of nicotine in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 1988;246:701–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Picciotto MR. Nicotine as a modulator of behavior: beyond the inverted U. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:493–499. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00230-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corrigall WA, Coen KM. Nicotine maintains robust self-administration in rats on a limited-access schedule. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1989;99:473–478. doi: 10.1007/BF00589894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corrigall WA, Franklin KB, Coen KM, Clarke PB. The mesolimbic dopaminergic system is implicated in the reinforcing effects of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;107:285–289. doi: 10.1007/BF02245149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dingman P, Resnick M, Bosworth E, Kamada D. A non-smoking policy on an acute psychiatric unit. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1988;26:11–14. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19881201-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greeman M, McClellan TA. Negative effects of a smoking ban on an inpatient psychiatry service. Hosp Commun Psychiatry. 1991;42:408–412. doi: 10.1176/ps.42.4.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith WR, Grant BL. Effects of a smoking ban on a general hospital psychiatric service. Hosp Commun Psychiatry. 1989;40:497–502. doi: 10.1176/ps.40.5.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beemer BR. Hospital psychiatric units. Nonsmoking policies. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1993;31:12–14. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19930401-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erwin S, Biordi D. A smoke-free environment: psychiatric nurses respond. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1991;29:12–18. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19910501-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haller E, McNeil DE, Binder RL. Impact of a smoking ban on a locked psychiatric unit. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57:329–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parks JJ, Devine D. The effects of smoking bans on extended care units at state psychiatric hospitals. Hosp Commun Psychiatry. 1993;44:885–886. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.9.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matthews LS, Diaz B, Bird P, et al. Implementing a smoking ban in an acute psychiatric admissions unit. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2005;43:33–36. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20051101-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris GT, Parle D, Gagne J. Effects of a tobacco ban on long-term psychiatric patients. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2007;34:43–55. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Velasco J, Eells TD, Anderson R, et al. A two-year follow-up on the effects of a smoking ban in an inpatient psychiatric service. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:869–871. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.8.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooke A. Maintaining a smoke-free psychiatric ward. Dimens Health Serv. 1991;68:14–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson KL, Larrabee JH. Tobacco ban within a psychiatric hospital. J Nurs Care Qual. 2006;21:24–29. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evins AE, Cather C, Culhane MA, et al. A 12-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study of bupropion sr added to high-dose dual nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation or reduction in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:380–386. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0b013e3180ca86fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quinn J, Inman JD, Fadow P. Results of the conversion to a tobacco-free environment in a state psychiatric hospital. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2000;27:451–453. doi: 10.1023/a:1021398427332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thorward SR, Birnbaum R. Effects of a smoking ban on a general hospital psychiatric unit. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1989;11:63–67. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(89)90028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffman BF, Eryavec G. Implementation of a no smoking policy on a psychiatric unit. Can J Psychiatry. 1992;37:74–75. doi: 10.1177/070674379203700122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryabik BM, Lippmann SB, Mount R. Implementation of a smoking ban on a locked psychiatric unit. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1994;16:200–204. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(94)90102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams JM. Eliminating tobacco use in mental health facilities: patients' rights, public health, and policy issues. J Am Med Assoc. 2008;299:571–573. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lawn S, Condon J. Psychiatric nurses' ethical stance on cigarette smoking by patients: determinants and dilemmas in their role in supporting cessation. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2006;15:111–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2006.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dani JA, Harris RA. Nicotine addiction and comorbidity with alcohol abuse and mental illness. Nature Neurosci. 2005;8:1465–1470. doi: 10.1038/nn1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.George TP, Ziedonis DM. Addressing tobacco dependence in psychiatric practice: Promises and pitfalls. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:353–355. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Appelbaum PS. Do hospitalized psychiatric patients have a right to smoke? Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:653–654. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.7.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.El-Guebaly N, Cathcart J, Currie S, Brown D, Gloster S. Public health and therapeutic aspects of smoking bans in mental health and addiction settings. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1617–1622. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bloor RN, Meeson L, Crome IB. The effects of a non-smoking policy on nursing staff smoking behaviour and attitudes in a psychiatric hospital. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2006;13:188–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jochelson K. Smoke-free legislation and mental health units: the challenges ahead. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:479–480. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.029942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lawn SJ. Systemic barriers to quitting smoking among institutionalised public mental health service populations: a comparison of two Australian sites. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2004;50:204–215. doi: 10.1177/0020764004043129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Etter M, Khan AN, Etter JF. Acceptability and impact of a partial smoking ban followed by a total smoking ban in a psychiatric hospital. Prev Med. 2008;46:572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weinberger AH, Krishnan-Sarin S, Mazure CM, McKee SA. Relationship of perceived risks of smoking cessation to symptoms of withdrawal, craving, and depression during short-term smoking abstinence. Addict Behav. 2008;33:960–963. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luk R, Cohen JE, Ferrence R, McDonald PW, Schwartz R, Bondy SJ. Prevalence and correlates of purchasing contraband cigarettes on First Nations reserves in Ontario, Canada. Addiction. 2009;104:488–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hyland A, Higbee C, Li Q, et al. Access to low-taxed cigarettes deters smoking cessation attempts. Am J Pub Health. 2005;95:994–995. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Joossens L. From public health to international law: possible protocols for inclusion in the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:930–937. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Callaghan RC, Tavares J, Taylor L. Another example of an illicit cigarette market: a study of psychiatric patients in Toronto, Ontario. Am J Pub Health. 2008;98:4–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.121954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lawn SJ, Pols RG, Barber JG. Smoking and quitting: a qualitative study with community-living psychiatric clients. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:93–104. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Campion J, Lawn S, Brownlie A, Hunter E, Gynther B, Pols R. Implementing smoke-free policies in mental health inpatient units: learning from unsuccessful experience. Austral Psychiatry. 2008;16:92–97. doi: 10.1080/10398560701851976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leavell NR, Muggli ME, Hurt RD, Repace J. Blowing smoke: British American Tobacco's air filtration scheme. Br Med J. 2006;332:227–229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7535.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hempel AG, Kownacki R, Malin DH, et al. Effect of a total smoking ban in a maximum security psychiatric hospital. Behav Sci Law. 2002;20:507–522. doi: 10.1002/bsl.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Solty H, Crockford D, White WD, Currie S. Cigarette smoking, nicotine dependence, and motivation for smoking cessation in psychiatric inpatients. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:36–45. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.LePage JP. The impact of a token economy on injuries and negative events on an acute psychiatric unit. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:941–944. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.7.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Green MA, Hawranik PG. Smoke-free policies in the psychiatric population on the ward and beyond: a discussion paper. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45:1543–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schnoll RA, Lerman C. Current and emerging pharmacotherapies for treating tobacco dependence. Exp Opin Emerg Drugs. 2006;11:429–444. doi: 10.1517/14728214.11.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Prochaska JJ, Gill P, Hall SM. Treatment of tobacco use in an inpatient psychiatric setting. Psychiat Serv. 2004;55:1265–1270. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hughes JR. Possible effects of smoke-free inpatient units on psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:109–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.D'Mello DA, Bandlamudi GR, Colenda CC. Nicotine replacement methods on a psychiatric unit. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27:525–529. doi: 10.1081/ada-100104516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tiffany ST, Drobes DJ. The development and initial validation of a questionnaire on smoking urges. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1467–1476. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hughes JR, Hatsukami DK. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.George TP, Vessicchio JC, Weinberger AH, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of bupropion combined with nicotine patch for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:1092–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Evins AE, Mays VK, Rigotti NA, Tisdale T, Cather C, Goff DC. A pilot trial of bupropion added to cognitive behavioral therapy for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:397–403. doi: 10.1080/14622200110073920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weiner E, Ball MP, Summerfelt A, Gold J, Buchanan RW. Effects of sustained-release bupropion and supportive group therapy on cigarette consumption in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:635–637. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Evins AE, Goff DC. Varenicline treatment for smokers with schizophrenia: a case series. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1016. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0620a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.George TP, Vessicchio JC, Termine A, et al. A placebo controlled trial of bupropion for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oncken C, Gonzales D, Nides M, et al. Efficacy and safety of the novel selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, varenicline, for smoking cessation. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1571–1577. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, et al. Varenicline, an alpha4 beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs. sustained release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation. JAMA. 2006;296:47–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, et al. Efficacy of Varenicline, an Alpha4 Beta2 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Partial Agonist, vs. Placebo or Sustained Release Bupropion for Smoking Cessation. JAMA. 2006;296:56–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Public Health Advisory. [cited March, 2009];Important information on Chantix (varenicline): U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2008 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/advisory/varenicline.htm.

- 82.Addington J, el-Guebaly N. Group treatment for substance abuse in schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1998;43:843–845. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.George TP, Ziedonis DM, Feingold A, et al. Nicotine transdermal patch and atypical antipsychotic medications for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1835–1842. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Horst WD, Klein MW, Williams D, Werder SF. Extended use of nicotine replacement therapy to maintain smoking cessation in persons with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2005;1:349–355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, Roll J. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2006;101:1546–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tidey JW, O'Neill SC, Higgins ST. Contingent monetary reinforcement of smoking reductions, with and without transdermal nicotine, in outpatients with schizophrenia. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;10:241–247. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hall SM, Tsoh JY, Prochaska JJ, et al. Treatment for cigarette smoking among depressed mental health outpatients: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1808–1814. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Steinberg ML, Ziedonis DM, Krejci J, Brandon TH. Motivational interviewing with personalized feedback: a brief intervention for motivating smokers with schizophrenia to seek treatment for tobacco dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;77:723–728. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Baker A, Richmond R, Haile M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a smoking cessation intervention among people with a psychotic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1934–1942. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Swanson AJ, Pantalon MV, Cohen KR. Motivational interviewing and treatment adherence among psychiatric and dually diagnosed patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187:630–635. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.West R. Helping patients in hospital to quit smoking. Dedicated counselling services are effective--others are not. BMJ. 2002:324–364. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brown RA, Kahler CW, Niaura R, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:471–480. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Petry NM. A comprehensive guide to the application of contingency management procedures in clinical settings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58:9–25. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Roll JM, Chermack ST, Chudzynski JE. Investigating the use of contingency management in the treatment of cocaine abuse among individuals with schizophrenia: a feasibility study. Psychiatry Res. 2004;125:61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Heil SH, Tidey JW, Holmes HW, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A contingent payment model of smoking cessation: effects on abstinence and withdrawal. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:205–213. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000074864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gallagher SM, Penn PE, Schindler E, Layne W. A comparison of smoking cessation treatments for persons with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses. J Psychoact Drugs. 2007;39:487–497. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Desai HD, Seabolt J, Jann MW. Smoking in patients receiving psychotropic medications: a pharmacokinetic perspective. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:469–494. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lyon ER. A review of the effects of nicotine on schizophrenia and antipsychotic medications. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:1346–1350. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.10.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vinarova E, Vinar O, Kalvach Z. Smokers need higher doses of neuroleptic drugs. Biol Psychiatry. 1984;19:1265–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Blumberg D, Safran M. Effects of smoking cessation on serum neuroleptic levels. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1269. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.9.1269a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ziedonis DM, Kosten TR, Glazer WM, Frances RJ. Nicotine dependence and schizophrenia. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45:204–206. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.3.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]