Abstract

Aspartate decarboxylase, which is translated as a pro-protein, undergoes intramolecular self-cleavage at Gly24–Ser25. We have determined the crystal structures of an unprocessed native precursor, in addition to Ala24 insertion, Ala26 insertion and Gly24→Ser, His11→Ala, Ser25→Ala, Ser25→Cys and Ser25→Thr mutants. Comparative analyses of the cleavage site reveal specific conformational constraints that govern self-processing and demonstrate that considerable rearrangement must occur. We suggest that Thr57 Oγ and a water molecule form an ‘oxyanion hole’ that likely stabilizes the proposed oxyoxazolidine intermediate. Thr57 and this water molecule are probable catalytic residues able to support acid–base catalysis. The conformational freedom in the loop preceding the cleavage site appears to play a determining role in the reaction. The molecular mechanism of self-processing, presented here, emphasizes the importance of stabilization of the oxyoxazolidine intermediate. Comparison of the structural features shows significant similarity to those in other self-processing systems, and suggests that models of the cleavage site of such enzymes based on Ser→Ala or Ser→Thr mutants alone may lead to erroneous interpretations of the mechanism.

Keywords: l-aspartate-α-decarboxylase/oxyanion hole/pyruvoyl-dependent enzymes/self-processing

Introduction

l-aspartate-α-decarboxylase (ADC) converts l-aspartate to β-alanine and provides the major route of β-alanine production in bacteria (Cronan, 1980). β-alanine is essential for the biosynthesis of pantothenate (vitamin B5), which occurs in bacteria, fungi and plants only.

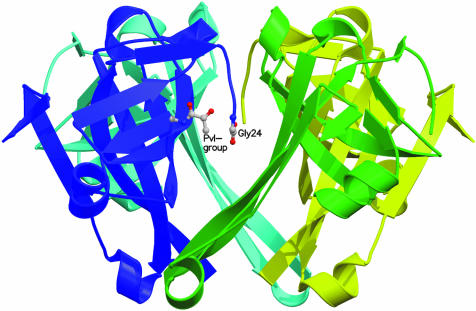

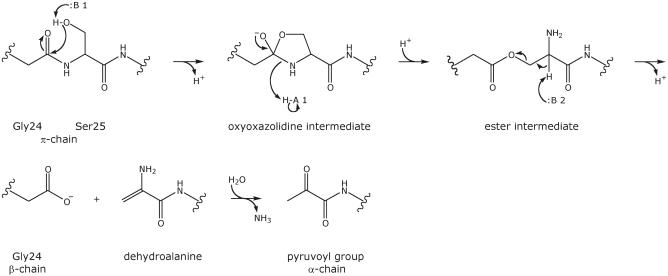

Escherichia coli ADC is a homotetramer, with a tertiary structure comprised of a six-stranded β-barrel (Albert et al., 1998) (pdb code: 1aw8) (Figure 1). In common with a group of mechanistically related pyruvoyl-dependent enzymes (van Poelje and Snell, 1990), it is translated as an inactive pro-enzyme (π-chain), which self-processes to create its own covalently bound prosthetic group, a pyruvoyl cofactor. The latter is formed by intramolecular, non-hydrolytic serinolysis, in which the side-chain oxygen of Ser25 attacks the carbonyl carbon of Gly24 (Figure 2). The reaction, which is also known as an N→O acyl shift, results in the formation of an ester in processing (Recsei et al., 1983), for which the crystal structures of processed, active ADC (Albert et al., 1998) and human S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (AdometDC) His242→Ala mutant (Ekstrom et al., 2001) have provided direct evidence. β-elimination of the ester produces dehydroalanine, which hydrolyses to form the pyruvoyl group. This process yields an α-chain of 11 kDa with the pyruvoyl group at the N-terminus and a β-chain of 2.8 kDa with Gly24 at the C-terminus (Ramjee et al., 1997). The overall mechanism is assumed to be essentially the same as in other pyruvoyl-dependent enzymes, the processed structures of three of which have been reported, namely Lactobacillus 30a histidine decarboxylase (HisDC) (Gallagher et al., 1993), human AdometDC (Ekstrom et al., 1999) and Methanococcus jannaschii arginine decarboxylase (ArgDC) (Tolbert et al., 2003a). Although all have their cleavage site located in a loop region between two β-strands, only ArgDC and HisDC are homologous to each other.

Fig. 1. The ADC tetramer, viewed with the internal four-fold axis in the plane of the paper, with the secondary structure of each subunit coloured differently. The pyruvoyl group (Pvl-group) and Gly24 of one subunit protomer in the foreground are shown in ball and stick representation (colour scheme as in Figure 4). Figures 1 and 6 were prepared with Molscript (Kraulis, 1991) and rendered in Raster3D (Merritt and Bacon, 1997).

Fig. 2. Schematic representation of the self-processing reaction, as it is currently understood, applied to ADC. Base 1, acid 1 and base 2 are designated as :B 1, H-A 1 and :B 2, respectively.

The mechanism of ADC processing is thought to be characteristic of self-catalysed backbone rearrangements in general, an important post-translational modification for protein maturation that is observed in a number of often evolutionarily and structurally unrelated proteins. Based on the fate of the ester intermediate, these can be classified into four systems (reviewed in Paulus, 2000): hedgehog proteins, inteins, N-terminal nucleophile (Ntn) hydrolases and pyruvoyl-dependent enzymes. An initial N→S or N→O acyl shift with a Cys, Ser or Thr nucleophile, resulting in a thioester or ester intermediate, respectively, is common to all four groups. The following step differs, but always results in breakdown of the activated ester. In Ntn hydrolases the ester is hydrolysed, generating a prosthetic N-terminal residue. In the hedgehog protein an intermolecular attack by cholesterol occurs, whereas in inteins the ester is intramolecularly attacked by a nucleophile from a spatially different region, which splices out the intein and ligates the two exteins together. Structural information for the processed form of the enzyme is available for the hedgehog protein (Hall et al., 1997), inteins (Duan et al., 1997), the proteasome (Lowe et al., 1995) and for several other Ntn hydrolases (Smith et al., 1994; Brannigan et al., 1995; Duggleby et al., 1995; Oinonen et al., 1995; Isupov et al., 1996; Kim et al., 2000). In contrast, structural information about unprocessed precursors of self-processing enzymes is relatively sparse. Structure solution of a native precursor has so far proved impossible and no unprocessed cleavage site from a self-processing enzyme that has not been mutated has been reported. Consequently, it is not known to what extent the cleavage site structures of mutants that have their nucleophilic Cys, Ser or Thr substituted resemble that of the native, unprocessed cleavage site. More structural data of self-processing enzymes in a pre-processed state are clearly necessary to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying molecular mechanism.

A general scheme of self-processing is shown in Figure 2. The main objective of this study was to investigate the roles of the evolutionarily conserved Gly24 and Ser25 in self-processing and to attempt to identify residues designated base 1, acid 1 and base 2 in the mechanistic scheme. First, we have been able to both prepare and crystallize a fraction of unprocessed native ADC, which is nonetheless competent for processing. We generated seven site-directed mutants. Four of these have a substitution at the cleavage site: Gly24→Ser (G24S), Ser25→Ala (S25A), Ser25→Thr (S25T) and Ser25→Cys (S25C). Two are insertion mutants, one with an Ala inserted between Glu23 and Gly24 (A24a-G24b) and one with an Ala inserted between Ser25 and Cys26 (S25a-A25b), in order to analyse the effect of the loop size. One, a His11→Ala (H11A) mutation, was made to investigate the possible role of this residue from an adjacent subunit in Hα proton abstraction from the ester intermediate.

Here we report the crystal structures of the unprocessed ADC pro-enzyme (pro-ADC) together with these seven mutants solved to between 1.29 and 2.00 Å minimum Bragg spacing. We present the structure of a native, unprocessed cleavage site, and a comparative structural investigation of it with the mutant structures. We suggest that this has implications for the interpretation of both mechanisms and precursor mutant structures in other self-processing systems.

Results and discussion

Protein preparation

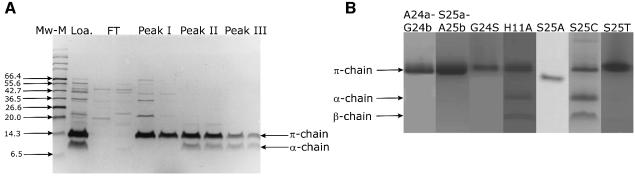

Native ADC on initial purification comprises a mixture of pro-enzyme (π-chain) and processed α- and β-chains (Ramjee et al., 1997). Further chromatography of this purified protein on MonoQ anion-exchange resin yielded three peaks (Supplementary data), the second and third of which again comprised a mixture of π-, α- and β-chains, as seen on SDS–PAGE (Figure 3A, lanes 7, 8 and 9, 10). In contrast, the first peak (peak I) was essentially unprocessed (Figure 3A, lanes 5 and 6), although western blotting revealed a trace amount of α-chain (Supplementary data). Re-chromatography of peak I on MonoQ resin again resulted in the three peaks, showing that the unprocessed enzyme from peak I, over time, converts into the processed enzyme of peaks II and III. This fractionation of ADC was possible because ADC processes significantly more slowly (Ramjee et al., 1997) than other self-processing enzymes. However, as observed previously for recombinant ADC (Ramjee et al., 1997), after storage at 4°C, the peak I fraction processed further, demonstrating that it was active and not merely a denatured fraction. This fraction (pro-ADC) therefore provided us with the opportunity to determine the structure of unprocessed ADC, which was nevertheless competent for processing.

Fig. 3. (A) SDS–PAGE of native ADC. Lane 1, molecular weight markers in kDa (Mw-M; the values are shown on the left); lane 2, native ADC before purification with anion-exchange chromatography (Loa.); lanes 3 and 4, flow-through (FT) of the MonoQ anion-exchange chromotography; lanes 5 and 6, peak I with the π-chain of pro-ADC; lanes 7 and 8, peak II with a mixture of π- and α-chain; lanes 9 and 10, peak III with a mixture of π- and α-chain. In the latter two the β-chain is present, but cannot be detected on SDS–PAGE. (B) PAGE of purified samples of ADC mutants. All proteins were histidine tagged, except S25A. All samples were analysed with tricine-PAGE, except A24a-G24b and S25a-A25b, which were analysed with SDS–PAGE. The band for S25A is lower, because of the missing histidine tag. The three bands in H11A and S25C represent π-chain, α-chain and β-chain, respectively.

The seven site-directed mutants A24a-G24b, S25a-A25b, G24S, H11A, S25A, S25C and S25T were generated as described in Materials and methods. Unlike S25A, which was purified similarly to native ADC, the other six mutants were purified as N-terminal histidine-tagged fusion proteins. Of the seven ADC mutants, only H11A and S25C were capable of forming significant amounts of α and β-chains in solution, within the time-span of the purification (Figure 3B). However, faint bands, corresponding to trace amounts of α- and β-chains were detected for all mutants in solution, except S25a-A25b and S25A, on prolonged storage and incubation (M.E.Webb, unpublished results).

As soon as possible after purification, pro-ADC and the seven mutants were crystallized. (NH4)2SO4 was used successfully as precipitant to give crystals, for pro-ADC at pH 5.5 and for all mutants, with the exception of S25A, at pH 4.0. The latter condition was closest to pH 4.6 under which processed ADC was crystallized (Albert et al., 1998). Crystals were in the same space group, P6122 (Table I), with two subunits in the asymmetric unit, which were related by the crystallographic two-fold axis to form the tetramer. S25A gave better crystals at pH 8.0 in tetragonal space group I422 (Table I), with the crystallographic four-fold axis coinciding with the internal four-fold axis of the tetramer. All structures were virtually isomorphous to the one from the processed ADC structure (Albert et al., 1998) (Table III), apart from the significant differences at the active site and its environment (see below). However, since only His11 is likely to have a pKa between 4 and 8 of the residues around the cleavage site, we would not expect major pH-dependent conformational changes in this region, in the pH range in which we crystallized the eight enzymes. Apart from S25T, which was cryo-protected with sodium malonate, all mutant crystals as well as pro-ADC crystals were cryo-protected with glycerol.

Table I. Crystallographic data statistics.

| Pro-ADC | A24a-G24b | G24S | H11A | S25a-A25b | S25A | S25C | S25T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||||||

| Space group | P6122 | P6122 | P6122 | P6122 | P6122 | I422 | P6122 | P6122 |

| Unit cell parameters (Å) a = b | 71.0 | 70.9 | 71.4 | 70.9 | 70.9 | 73.1 | 70.9 | 70.5 |

| c | 216.4 | 218.7 | 219.1 | 217.1 | 217.7 | 111.1 | 217.1 | 215.3 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 62–1.95 | 25–1.9 | 25–2.0 | 25–1.90 | 25–2.0 | 25–1.95 | 30–1.90 | 60–1.29 |

| highest resolution shell | 2.01–1.95 | 1.94–1.90 | 2.05–2.00 | 1.94–1.90 | 2.05–2.00 | 2.02–1.95 | 1.92–1.90 | 1.30–1.29 |

| No. of unique reflections | 24 605 | 26 749 | 23 414 | 26 557 | 23 013 | 11 321 | 26 469 | 81 391 |

| multiplicity | 17.9 | 29.3 | 30.9 | 33.5 | 28.7 | 9.3 | 29.8 | 52.5 |

| Rsyma | 5.9 | 5.1 | 7.8 | 8.7 | 6.4 | 4.0 | 8.2 | 9.7 |

| highest resolution | 29.0 | 29.8 | 34.5 | 26.0 | 19.1 | 32.8 | 32.3 | 77.0 |

| Average I/σ(I) | 24.5 | 45.8 | 33.8 | 31.2 | 37.5 | 36.6 | 28.3 | 25.7 |

| highest resolution | 3.2 | 9.6 | 5.0 | 9.8 | 10.7 | 4.2 | 3.0 | 4.4 |

| % completeness | 96.4 | 99.4 | 98.6 | 100 | 99.7 | 95.2 | 98.9 | 99 |

| highest resolution | 89.3 | 100 | 90.5 | 100 | 99.3 | 92.7 | 88.3 | 97.9 |

| Wilson B (Å2) |

24.8 |

24.6 |

24.9 |

16.1 |

23.4 |

26.7 |

31.7 |

15.3 |

| Refinement | ||||||||

| Rcrystb | 15.9 | 17.4 | 16.3 | 15.0 | 17.4 | 16.1 | 17.4 | 15.4 |

| highest resolution | 19.6 | 19.6 | 18.5 | 16.8 | 17.2 | 17.7 | 23.2 | 23.4 |

| Rfreec | 20.2 | 18.3 | 18.2 | 17.2 | 19.1 | 20.4 | 19.5 | 16.7 |

| highest resolution | 23.0 | 26.8 | 22.7 | 20.4 | 18.9 | 20.6 | 26.8 | 24.7 |

| No. of reflections: working/test | 22 229/1183 | 25 184/1337 | 21 839/1180 | 24 507/1928 | 21 139/1169 | 10 244/518 | 24 377/1325 | 76 434/4045 |

| No. of non-H atoms | ||||||||

| protein | 1793 | 1793 | 1876 | 1779 | 1755 | 902 | 1793 | 1865 |

| water | 274 | 166 | 237 | 240 | 170 | 141 | 183 | 387 |

| ligand |

5 |

20 |

10 |

20 |

5 |

0 |

10 |

22 |

| Model quality | ||||||||

| Estimated coordinate error (Å)d | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| R.m.s. deviation bonds (Å)e | 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.011 |

| R.m.s. deviation angles (°)e | 1.60 | 1.56 | 1.57 | 1.44 | 1.59 | 1.56 | 1.56 | 1.45 |

| No. of residuesf | ||||||||

| in most favoured region | 221 | 225 | 232 | 220 | 219 | 110 | 220 | 224 |

| in generously allowed region | 6 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 6 |

| in disallowed region | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

aRsym = ΣhΣi|Ihi–Ih| / ΣhΣiIhi, where Ihi are symmetry-related intensities and Ih is the mean intensity of the reflection with unique index h.

bRcryst = Σ||Fobs|–|Fcalc||/Σ|Fobs|; Fobs and Fcalc: observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes.

cRfree: cross-validation of Rcryst (Brunger, 1992).

dEstimated coordinate error of the structure based on the R-value as calculated by Refmac (Murshudov et al., 1997).

eR.m.s. (root mean square) deviation as calculated with WHATCHECK (Hooft et al., 1996).

fφ/ψ angles calculated and evaluated with RAMPAGE (Lovell et al., 2003).

Table III. Data from the comparative structural analysis.

| Pro-ADC | A24a-G24b | G24S | H11A | S25a-A25b | S25A | S25C | S25T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average B-factor (Å2)a | ||||||||

| protein (all non-H atoms) | 35 | 33 | 33 | 19 | 31 | 35 | 39 | 19 |

| water | 44 | 42 | 38 | 32 | 38 | 45 | 48 | 35 |

| Average B-factor for His21 | 71 | 87 | 86 | 42 | 75 | 79 | 90 | 54 |

| (Å2)a (all non-H atoms) | 112 | 80 | 99 | 62 | 92 | 58 | 56 | |

| Average B-factor for Tyr22 | 45 | 95 | 74 | 35 | 60 | 95 | 114 | 63 |

| (Å2)a (all non-H atoms) | 94 | 56 | 69 | 62 | 75 | 63 | 72 | |

| Average B-factor for Glu23 | 59 | 95 | 56 | 29 | 56 | 75 | 129 | 37 |

| (Å2)a (all non-H atoms) | 90 | 56 | 49 | 52 | 76 | 53 | 54 | |

| Main-chain r.m.s. difference for residues 1–16, 26–71, 77–115 with protomer B of pro-ADC (Å)b | 0.300 | 0.250.31 | 0.360.33 | 0.310.23 | 0.280.21 | 0.30 | 0.280.26 | 0.360.29 |

| Main-chain r.m.s. difference for residue 24 (Å)b,c | 0.29 (0.44) | 0.83 (0.92) | 0.60 | 0.98 (1.61) | 2.14 | 2.15 (2.93) | 8.04 | 3.53 (3.55) |

| (all-atom r.m.s. difference) | 0 | 1.06 (1.02) | 0.57 | 0.97 (1.43) | 0.38 | 7.41 | 3.66 (3.66) | |

| Main-chain r.m.s. difference for residue 25 (Å)b,c | 0.08 (0.15) | 0.20 (0.31) | 0.39 (0.44) | 0.30 (0.50) | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.47 | 3.00 |

| (all-atom r.m.s. difference) | 0 | 0.30 (0.39) | 0.23 (0.25) | 0.17 (0.17) | 0.43 | 0.40 | 3.04 | |

| φ/ψ angles of Thr57 (°) | –148/–145 | –148/–146 | –151/–152 | –150/–152 | –157/–146 | –154/–149 | –151/–148 | –156/–155 |

| –152/–148 | –154/–152 | –156/–154 | –146/–151 | –153/–148 | –151/–151 | –154/–155 | ||

| Distance Gly24 O to Thr57 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 8.6 | 6.2 | 9.8 | 6.1 |

| Oγ (Å) | 2.7 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 7.5 | 9.4 | 6.1 | |

| Distance Oγ of residue 25 to | 4.3 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.7 | – | – | 3.7 |

| C of residue 24 (Å) | 4.1 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 3.7 | ||

Two values in the column indicate values for protomers A and B, respectively.

aAverage B-factor includes contribution from the TLS group.

bSuperposition of main-chain atoms of residues 1–16, 26–71, 77–115 with the respective residues of protomer B of pro-ADC.

cResidues used for the superposition as in footnote b. Where possible (where the residue identity is the same and in the same position) an all-atom r.m.s. difference was calculated. The latter value is shown in parentheses.

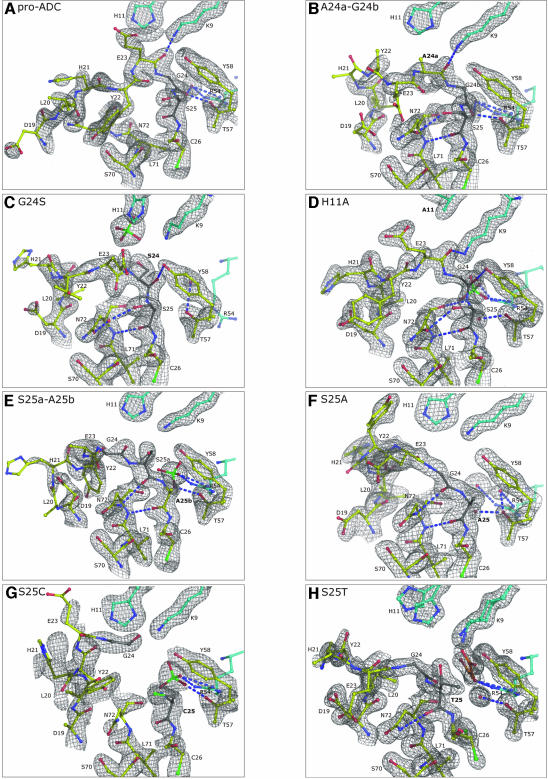

A summary of the crystallographic data statistics for the final models is shown in Table I. Table II comprises the relevant structural features of the cleavage site in each of the ADC structures together with information about processing activity, whereas Table III contains more detailed comparative data of the structural differences.

Table II. Summary of processing activity (in solution) and structural features of the various enzymes.

| Enzyme | Processing activity | Structural features |

|---|---|---|

| Pro-ADC | Yes | Apart from differences in residues 17–25 and 72–77 the structure is essentially identical to the processed ADC structure (Albert et al., 1998). Gly24 has φ/ψ angles of 97/13° and 92/6° in subunits A and B. Residues 21–23 in the ψ-loop preceding Gly24 are disordered. There are conformational differences in this region in the two subunits and also for the highly conserved 310 helical region between Asn72 and Ala76, which lies adjacent to the loop. We use subunit B for comparison with other mutant structures, because the 310 helix superposes better with that in processed ADC. |

| A24a-G24b | Traces | The conformation of the Gly24b–Ser25 peptide bond is very similar to that in pro-ADC. However, there are significant differences in the ψ-loop. |

| G24S | Traces | The conformations of Glu23–Ser24 and Ser24–Ser25 peptide bonds are different from those in pro-ADC. The Gly24 carbonyl does not H-bond to Thr57. |

| H11A | Yes | The protein that crystallized was essentially the π-chain. The unprocessed cleavage site is shifted towards Ala11. Apart from the difference of the Gly24 carbonyl the structure is very similar to pro-ADC. |

| S25a-A25b | No | S25a carbonyl in subunit A is rotated by ∼180° from its position in pro-ADC. Ala25b is in the same conformation and position as Ser25 in pro-ADC and Ala25 in S25A. |

| S25A | No | Gly24 carbonyl is rotated by ∼180° from its position in pro-ADC. Conformation and position of Ala25 are identical to that of Ser25 in pro-ADC. |

| S25C | Yes | The protein that crystallized was essentially the α- and β-chains. There is a free Cys25, instead of the pyruvoyl group, at the N-terminus of the α-chain. Additional electron density adjacent to the Cys could be the result of the unprocessed cleavage site at low occupancy. |

| S25T | Traces | The Gly24–Thr25 peptide bond is in a different position and conformation from that in the cleavage site in pro-ADC. No H-bonds between Gly24 carbonyl and Thr57 nor between Thr25 O and Asn72 N. |

Interactions at the cleavage site

Specific interactions at the cleavage site have been identified in mutated precursors of the proteasome (Ditzel et al., 1998) and glycoslyasparaginase (Xu et al., 1999). These were assumed to guarantee optimal conformation of the cleavage site and assist the self-processing catalysis by stabilization of reaction intermediates. In this study, comparative analysis of the various ADC structures shows that residues in positions 24 and 25 in the two subunits in the asymmetric unit superpose very well, with the exception of those in S25a-A25b, where two conformations are seen for the Ser25a carbonyl. However, this coincidence in position of residues 24 and 25 in the two subunits is in contrast to residues 21–23 in the ψ-loop preceding the cleavage site. The rigidity of Gly24 and Ser25 appears to result from the following interactions (Figure 4A): (i) strong H-bonds of the Gly24 carbonyl to the Oγ of the invariant Thr57 and to a water molecule; (ii) a H-bond between the Ser25 carbonyl and the main-chain nitrogen of Asn72: Asn72 is almost completely conserved (Figure 5) and only in a thermophilic bacterium is it a Tyr; (iii) a H-bond between the Glu23 main-chain carbonyl oxygen and the Nζ of the invariant Lys9 from an adjacent subunit.

Fig. 4. Electron density maps of the 2Fo–Fc type, of the self-cleavage site and its environment, contoured at 1.2σ. Colour scheme: carbon atom of the protein, yellow; carbon of the self-cleavage site, dark grey; carbon of the protein from an adjacent subunit, cyan; carbon atom of non-protein, orange; nitrogen, blue; oxygen, red; sulfur, green; H-bonds, light blue dashed lines. Arg54 is shown without electron density. All figures are from subunit A, except S25C, in a similar orientation and show Asp19–Cys26, Ser70–Asn72, Thr57 and Tyr58 as well as Lys9, His11 and Arg54 from an adjacent subunit. The mutations are shown in bold letters. (A) Pro-ADC. Side chains of residues 21–23 in the ψ-loop are disordered. In contrast to subunit B, Asn72 is below rather than between the loop and Tyr22 lies in between Asn72 and Ser25. (B) A24a-G24b. Residues 21 and 22 were modelled as Ala. (C) G24S, (D) H11A. Glu23 is occupying the space of the removed imidazole ring. Gly24 is H-bonding to the Tyr58 (2.97 Å). A sulfate and a water molecule are occupying the space between Gly24 and Thr57. (E) S25a-A25b. Gly24 H-bonds to Asn72. A sulfate is H-bonding to Thr57 and Arg54. Note the more extended conformation of Ser25a. (F) S25A. The carbonyl group of Gly24 H-bonds to the Oδ of Asn72. Note the similarity of the extended conformation of Gly24 to Ser25a in S25a-A25b (G) S25C, (H) S25T. A malonic acid residue and a water, H-bonding to Arg54 and Thr57, respectively, lie in between Thr25 and Thr57. Tyr22 is modelled as Ala. Figures 4 and 7 were prepared with PyMOL (DeLano, 2002).

Fig. 5. Structure-annotated (Mizuguchi et al., 1998) sequence of ADC. Invariant residues in the environment of the self-cleavage site are indicated with a *, conserved residues are indicated with a +. A key to JOY format can be found at: http://www-cryst.bioc.cam.ac.uk/~joy/fig1.pdf.

The H-bond to the Thr57 Oγ, appears to be important for orienting the carbonyl, and additionally may polarize the Gly24 carbonyl bond. Together with the well-ordered water molecule (Figure 4A), Thr57 forms an ‘oxyanion hole’ that is likely to stabilize the developing negative charge on the exo-cyclic oxygen (Figure 2). The water molecule, whose position is stabilized by two H-bonds to the Nη1 and Nη2 of the invariant Arg54, is at a distance of 2.6 Å from the Gly24 carbonyl oxygen in the pro-ADC structure and is in the same position in the processed ADC structure. In all structures Thr57 is in the same, generously allowed, region of the Ramachandran plot (Table III), implying a functional role. Its conformation and position is maintained before and after self-processing. Asn72 is followed by a sequence of highly conserved residues forming a 310 helix (Figure 5), whose role appears to be mainly structural and could serve to restrict the conformations of the ψ-loop.

Conformational constraints

Detailed knowledge of the differences in the conformations of the cleavage site in the various structures can be helpful in understanding the relevance of the conformation for self-processing. In pro-ADC, Gly24 of the unprocessed cleavage site has a positive φ (Table II) and is in a left-handed α-helical conformation. Any other residue in this position with the same conformation as this Gly would almost certainly introduce steric clashes. Consequently, in the structure of the inactive G24S mutant, the Ser24 carbonyl is in a different conformation (Figure 6A), positioned away from Thr57 (Figure 4C). However, introducing a residue before Gly24, as in A24a-G24b, does not alter the conformation of the cleavage site (Figure 4B) and leaves the geometry (Figure 6B) as well as the interactions of the cleavage site, observed in pro-ADC, intact. Nevertheless this mutant interestingly does not process. Consequently, in addition to the interactions and geometry of the cleavage site other factors appear to be influential for processing. Strain in the loop has been assumed to contribute to the self-processing reaction in pyruvoyl-dependent HisDC (Gallagher et al., 1993), intein splicing (Klabunde et al., 1998) and glycosylasparaginase (Xu et al., 1999). In pro-ADC we could not find evidence for strain in the form of significant deviations in ω and τ angles or unusual peptide conformations in the peptide bonds of Glu23-Gly24 and Gly24-Ser25. However, in the eight structures of ADC presented here, side chains of His21, Tyr22 and Glu23 in the ψ-loop are disordered (Figure 4A–H) and/or found in different conformations in the two subunits, even though the position of Gly24–Ser25 is constrained. Making the loop longer as in A24a-G24b and also in S25a-A25b leads to increased conformational heterogeneity, as shown by the very different conformations the loop adopts in the two subunits. Presumably, the added residue in A24a-G24b renders the loop incapable of stabilizing reaction intermediates of the self-processing reaction. Whereas a single defined conformation of the loop itself does not seem to be essential, we suggest that a certain degree of conformational flexibility may be an important factor in allowing the processing to proceed.

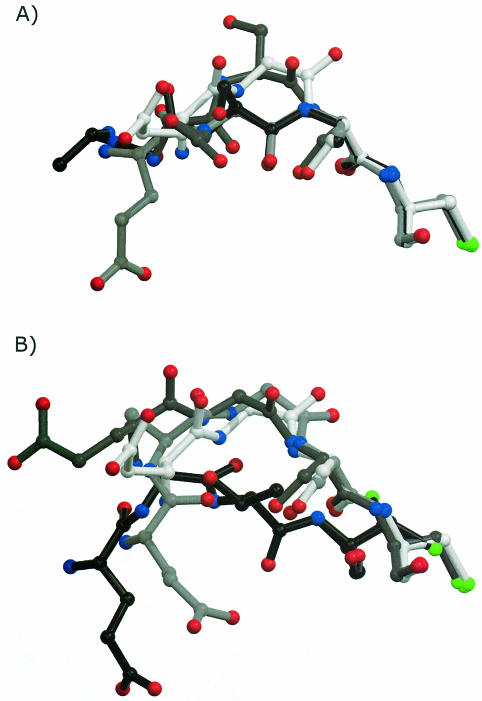

Fig. 6. Superposition of Glu23 (left) to Cys26 (right) with the procedure described in the legend to Table III. From all structures subunit A was used, except in pro-ADC. Colour scheme as in Figure 4. (A) Carbon: pro-ADC, white; G24S, dark grey; S25a-A25b, black; S25A, light grey. Note the almost identical position of the Gly24 carbonyl in S25a-A25b and S25A. (B) Carbon: pro-ADC, white; A24a-G24b, light grey; H11A, dark grey; S25T, black. Note the shift in the cleavage site in H11A, relative to pro-ADC.

The second insertion mutant S25a-A25b, like A24a-G24b, is also inactive. However, in this mutant the cleavage site is moved out of its normal environment. Ala25b is in exactly the same place as Ser25 in pro-ADC and Ala25 in S25A (Figure 6A). Significantly, removal of the side-chain hydroxyl of Ser25, as in both the inactive S25A mutant and, effectively, S25a-A25b, causes a change in the conformation of the Gly24 carbonyl. It is rotated by ∼180° from its position in pro-ADC, H-bonding to Asn72 instead of Thr57 (Figure 4E and F). This conformational change results in a more extended conformation of Gly24. When the Ser25 hydroxyl was present, as in pro-ADC, steric hindrance with the Gly24 carbonyl would most likely prevent such a conformation. However, the bulkier side chain of a Thr in the position of Ser25, as in the inactive S25T, appears to force Gly24, Thr25 and Cys26 out of their normal environment (further to the left, from the perspective in Figure 4). There are no H-bonds between the Gly24 carbonyl and the Thr57 Oγ (Figure 4H). The structural differences in this mutant represent the most pronounced change in the position of the cleavage site in all mutant structures (Figure 6B). In the structure of the active, but unprocessed, H11A mutant the conformation of the cleavage site is similar to that of pro-ADC, with the exception of the Gly24 carbonyl, which H-bonds to Tyr58 instead of Thr57. The removal of the imidazole group created a cavity that is occupied by Glu23, whose Cα position is 1.75 Å further towards residue 11 compared with the position in pro-ADC. The transition state for processing of this mutant apparently can nevertheless be similar to that for pro-ADC with the carbonyl of Gly24 H-bonded to Thr57. Such a conformation is readily accessible from the observed ground state structure without major rearrangement.

This analysis clearly demonstrates that deducing the conformation and geometry of the cleavage site from the structures of the inactive S25A and S25T mutants, by computationally modelling a Ser in place of Ala or Thr, would have led to incorrect models for the native, unprocessed peptide bond. As a consequence, the putative oxyanion hole would not have been identified. Even very modest changes in the active site, as in H11A, can result in a different observed ground state of the protein. The differences in the structures indicate that small but important changes apparently account for the loss of processing activity. Tight conformational constraints, including H-bonds and steric effects, define the optimal geometry of the cleavage site. Seemingly conservative substitutions can lead to significant conformational changes, to which self-processing in ADC is very sensitive.

Molecular mechanism of self-processing in ADC

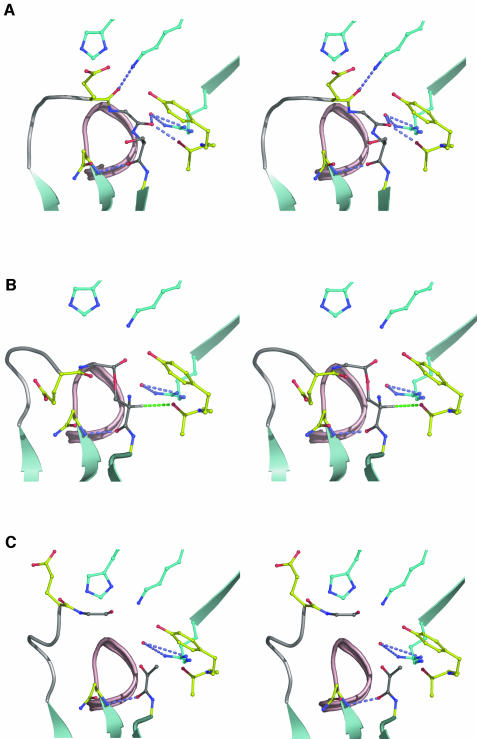

Based on the structure of the native cleavage site and knowledge of the coordinates for the ester as well as the pyruvoyl group (Albert et al., 1998), we can propose a mechanism for the cleavage reaction. The N→O acyl shift is initiated by a nucleophilic attack of the Ser25 Oγ on the carbonyl carbon of Gly24 (Figure 2). The Gly24 carbonyl bond is held in the specific conformation observed in the pro-ADC structure in which it forms H-bonds to both the Oγ of Thr57 and the water residue (Figure 7A). The optimal trajectory for nucleophilic attack by the Ser25 hydroxyl requires the angle between the Gly24–Ser25 peptide plane and the O=C–Oγ plane (O=C of the Gly24 carbonyl and Ser25 Oγ) to be approximately orthogonal. However, in pro-ADC this angle between the Gly24–Ser25 peptide plane and the O=C–Oγ plane is <11°, and in addition the Ser25 Oγ is >4 Å away from the Gly24 carbonyl carbon (Table III). Consequently, considerable rearrangement of Ser25 towards Gly24 is necessary, in order to allow attack on the carbon and for the cleavage reaction to occur. Furthermore, a certain degree of conformational flexibility, described above, of the preceding loop appears to be required.

Fig. 7. Stereo figures of the structures of the three states of processing in ADC. Colour scheme as in Figure 4. Additional colour scheme: hydrogen, white; ψ-loop, light grey; 310 helix, light-red; β-strand, light-blue. (A) The unprocessed cleavage site of pro-ADC (subunit B). (B) The ester intermediate observed at half occupancy in the processed ADC structure (Albert et al., 1998); indicated by a green dashed line is a possible line of the Hα proton abstraction by the Thr57 Oγ. (C) The processed ADC structure with the pyruvoyl group (Albert et al., 1998). The Cα atom of Gly24 is now ∼8 Å away from its position in pro-ADC.

It has been assumed that a specific residue, base 1 of Figure 2, would act as a general base to enhance the nucleophilicity of the Ser25 Oγ. However, the residues in close vicinity that could directly or indirectly mediate this effect, Tyr58 and Asn72, have each been shown by mutagenesis to phenylalanine and alanine, respectively, not to be vital for processing (M.E.Webb et al., in preparation). The Oη of Tyr22 seems to be too far away in the structures, although a major conformational change in this loop cannot be excluded. Consequently, it is possible that in the hydrophilic environment of Ser25 Oγ there is no specific residue for a general base.

As we have seen, the Gly24 carbonyl forms H-bonds to both the Oγ of Thr57 and the water residue, which may help processing by polarizing it and making the carbonyl more susceptible to a nucleophilic attack. Subsequent to the initial nucleophilic attack, a transient oxyoxazolidine intermediate with a tetrahedral Gly24 carbon must be formed. In ADC the resulting negative charge on the oxygen (Figure 2) could be stabilized by the H-bonds to Thr57 Oγ and the water molecule, which together effectively form the oxyanion hole. Assuming that the oxygen anion is in a position similar to that of the Gly24 carbonyl oxygen in pro-ADC (Figure 7A), the oxyanion hole is ideally positioned to provide stabilization. Subsequent breakdown of the oxyoxazolidine intermediate necessitates protonation of the nitrogen, by acid 1 (Figure 2), which may come from the water molecule or the Thr57 Oγ. The Thr57 Oγ could then act as base 2 (Figure 2), for the subsequent Hα abstraction of the ester intermediate (Figure 7B). Thr57→Ala and Thr57→Val mutants were unable to self-process (M.E.Webb et al., in preparation), consistent with its central role. Apart from the main-chain H-bond between Asn72 and residue 25, none of the interactions identifiable in the cleavage site prior to processing are present anymore in the structure of the ester intermediate in processed ADC (Albert et al., 1998). This indicates the conformational rearrangements that have taken place. Upon breakdown of the ester, the Gly24 carboxyl end moves away (Figure 7C) and the loop residues become more ordered (Albert et al., 1998).

This model of the molecular mechanism provides a rationale for why S25A, G24S, S25T, A24a-G24b and S25a-A25b do not process and why H11A and S25C do. The S25A mutant lacks the Oγ and so cannot process. In G24S the conformation of the Gly24 carbonyl is altered significantly. In addition the H-bonds between the Gly24 carbonyl and Thr57 and the water molecule are not present. The same applies to S25T, where the Gly24 carbonyl oxygen is >5.8 Å away from the Thr57 Oγ. The insertion mutants A24a-G24b and S25a-A25b do not process because of the altered conformational freedom of the loop. Additionally, in S25a-A25b Gly24 is too far away to interact with Thr57. The H11A structure appears to be able to access a similar transition state to pro-ADC, in order to process. S25C does process in solution and the fraction that crystallized contained predominantly the processed α- and β-chains. The free Cys at the N-terminus of the α-chain of processed S25C, observed in the structure (Figure 4G), presumably arises by non-productive hydrolysis of the more reactive thioester intermediate. The latter may be especially susceptible to hydrolysis under the acidic crystallization conditions around pH 4.

Comparison with other self-processing systems and implications

Protein self-processing occurs as a protein maturation event in evolutionarily unrelated eukaryotic and prokaryotic enzymes. The cleavage site is comprised of Glu–Ser in pyruvoyl-dependent AdometDC and Ser–Ser in both pyruvoyl-dependent ArgDC and HisDC. In pyruvoyl-dependent phosphatidylserine decarboxylase (PsDC) the cleavage site is formed by Gly–Ser, whereas in subunits of pyruvoyl-dependent glycine-, proline- and sarcosine reductase, it consists of Asn/Thr–Cys (van Poelje and Snell, 1990; Bednarski et al., 2001). Ser→Cys and Ser→Thr mutants of the cleavage site Ser in HisDC, AdometDC and PsDC were able to process at significantly reduced rates (Vanderslice et al., 1988; Xiong et al., 1997). Abortive chain cleavage without pyruvoyl formation, which occurred in these mutants in HisDC, was most likely the result of hydrolysis of the ester, similar to S25C ADC.

In the unprocessed structure of the Ser53→Ala mutant of precursor ArgDC the modelled Ser53 side chain was positioned to attack the si-face of the Ser52 carbonyl (Tolbert et al., 2003a). It was proposed that the Ser52 side chain could function as part of an oxyanion hole. Based on our work, an alternative conformation of this carbonyl in the native cleavage site H-bonding to the Oδ of the invariant Asn47 seems plausible. In order to H-bond to Asn47 the carbonyl would have to adopt a conformation pointing in an almost opposite direction to that in the S53A mutant structure. This would provide a role for Asn47, which is one of only three invariant residues in ArgDC (Tolbert et al., 2003a), in the self-processing mechanism.

In AdometDC, the side-chain amine of a His is assumed to be base 2 for the Hα proton abstraction (Ekstrom et al., 2001), but no oxyanion hole could be identified. In the precursor Ser68→Ala mutant structure the Glu carbonyl of the Glu–Ser cleavage site is H-bonding to the Sγ of the variant Cys82 (Tolbert et al., 2003b). Based on our work and on comparison with other systems we consider that this conformation may not be representative of the native cleavage site and led us to a different interpretation. A conformation with the carbonyl pointing in the opposite direction would provide a role for the Oγ of the invariant Ser229 as part of an oxyanion hole. In contrast to Cys82 (Xiong et al., 1999), the hydroxyl group of Ser229 was shown by mutagenesis to be essential for processing (Xiong and Pegg, 1999).

The Oγ of an invariant Ser (Ser129) forms part of an oxyanion hole in the β-subunit of the proteasome (Ditzel et al., 1998) and polarizes the Gly carbonyl. The Ser129→Ala mutation completely abolished processing (Seemuller et al., 1996). The Gly of the conserved Gly–Thr cleavage site makes a kink in the Thr1→Ala precursor mutant structure, similar to that in pro-ADC.

Interestingly, a conserved Thr, whose Oγ can form part of an oxyanion hole as in ADC, was also identified in the hedgehog protein (Hall et al., 1997), in inteins (Klabunde et al., 1998) as well as in the Ntn glycosylasparaginase (Xu et al., 1999). The Oγ of this Thr H-bonds to the carbonyl, which is attacked by the nucleophile in the GyrA intein structure (Klabunde et al., 1998) and is in a similar position both in the structures of the VMA29 intein Cys1→Ala mutant (Poland et al., 2000) and in the VMA1-derived intein precursor quadruple mutant (Mizutani et al., 2002). However, again extrapolating from ADC, the carbonyl in the latter two may not be in its native conformation, since it either lacks any close H-bonding donors or points away from the side chains of the conserved Thr and His, which could contribute to an oxyanion hole. In the unprocessed Thr152→Cys mutant structure of glycosylasparaginase (Xu et al., 1999) the Thr170 Oγ and a water residue H-bond to the carbonyl oxygen of the cleavage site and form an oxyanion hole. Mutagenesis studies of Thr170 confirmed its key role (Guo et al., 1998). The relative position of the Thr, the carbonyl and the oxyanion hole are strikingly similar to ADC. Asp151 in the conserved Asp151–Thr152 cleavage site makes a kink that has some similarity to that of Gly24 in ADC. A Thr152→Ser mutant was able to process, whereas Asp151 is essential for processing (Guan et al., 1996).

The structures of Ser→Ala mutants of the Gly–Ser cleavage site in the Ntn cephalosporin acylase (CA) (Kim et al., 2002) and the Ntn glutaryl-7-aminocephalosporanic acid acylase (GCA) (Kim et al., 2003) indicated that a water molecule could function as the base to increase the nucleophilicity of the Ser Oγ. In both enzymes the main-chain nitrogen of a His could stabilize a developing negative charge.

Only in GCA, CA and in glycosylasparaginase, but not in any of the other self-processing enzymes could a specific residue for a general base, base 1, be identified. This suggests that general base catalysis by a specific residue may not be a requirement for the initial nucleophilic attack. However, there does appear to be a preference for the location of the self-cleavage site in between two β-strands or at the beginning of a β-strand. Although no single structural motif is used for the cleavage site, Gly is the most common residue preceding the nucleophile in self-processing systems, presumably due to its conformational adaptability. In contrast to glycosylasparaginase and the GyrA intein, we have not found evidence for the role of strain in processing in ADC. Comparison with other self-processing systems implies that the oxyanion hole is a crucial, general requirement for self-processing. Thus, stabilization of the oxyoxazolidine intermediate could be the important step to drive the reaction. Interestingly, this stabilization in most of the self-processing systems is different from the oxyanion hole identified in serine proteases, which is formed mainly by hydrogens from main-chain nitrogens. This could be a consequence of the multiple roles the stabilizing groups have in self-processing systems, to both polarize the carbonyl bond in the first step in the reaction and stabilize the resulting negative charge in the second step. Our results also sound a cautionary note about both the interpretation and the relevance of models and mechanisms, based solely on the structure of Ser→Ala or Ser→Thr mutants, in other self-processing systems.

The results of our study on E.coli ADC are relevant to ADCs from pathogenic bacteria (Kwon et al., 2002), which are potential drug targets, since the key residues are invariant throughout all sequences. Further structural information on the cleavage reaction is useful in understanding the respective biochemistry and can aid in producing drugs to prevent protein maturation. The molecular mechanism of ADC is likely to have significant parallels in other self-processing systems.

Materials and methods

General methods

Chemicals used were purchased from Sigma or Fluka, unless stated otherwise. Standard molecular methods were as described (Sambrook et al., 1989). DNA sequencing and electrospray mass spectrometry were carried out by the PNAC facility, Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge. The latter and MWG Biotech provided primers. Restriction enzymes and DNA polymerase were from New England Biolabs.

Mutagenesis and plasmid construction

All primer information is given in the Supplementary data. Plasmid pDKS1 with an ADC coding sequence (Ramjee et al., 1997) was used as a template in a divergent PCR to create a S25A mutation. The purified PCR product was digested with KasI, religated and transformed into E.coli XL1-B. A24a-G24b, G24S, H11A, S25a-A25b, S25C and S25T mutations were constructed by double-PCR. A24a-G24b, G24S, H11A, S25a-A25b, S25C and S25T were then cloned into pRSETA vector (Invitrogen) with a coding sequence for an N-terminal histidine tag. After amplification with Pfu DNA polymerase, the purified (Qiagen) PCR product was cloned into pRSETA plasmid using NcoI and BamHI sites.

Overexpression and purification

S25A and pro-ADC were overexpressed as described previously (Ramjee et al., 1997). ADC mutants with an N-terminal histidine tag were overexpressed in E.coli C41 (DE3) cells. Cells were grown in LB or 2YT medium (DIFCO) containing ampicillin (100 µg/ml), at 37°C. At an OD600 of 0.3–0.4 expression was induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (1 mM). Cells were then grown for 3–4 h and centrifuged for 30 min at 4300 r.p.m. (Beckmann 1059G).

Purification of ADC and analysis of the protein samples were carried out as described previously (Ramjee et al., 1997). Further purification with anion exchange chromatography (MonoQ, Pharmacia), with a 200 mM K2HPO4/KH2PO4 buffer gradient yielded three peaks for ADC, which by tricine–PAGE (Schagger and Von Jagow, 1987) and western blotting were shown to contain ADC in varying degrees of processing. The first peak, eluting at 50 mM K2HPO4/KH2PO4 concentration, contained the unprocessed form (pro-ADC) and was dialysed with 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA. The second and third peaks contained π-, α- and β-chains in different proportions. S25A was purified as for processed ADC (Ramjee et al., 1997). For all other mutants the cell pellet was resuspended in a buffer of 50 mM Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl (buffer A) and 10 mM imidazole. After sonication on ice and centrifugation at 19 000 r.p.m. (Sigma 12150), the supernatant was filtered (0.22 µm filter, Millipore) and loaded on a Ni-NTA column (Qiagen). Protein was eluted with buffer A containing 250 mM imidazole. Concentrated protein fractions were loaded on a Superdex200 (Pharmacia) size exclusion chromatography column and eluted with 25 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid/NaOH pH 7.4 or 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.0. Protein samples were assessed by PAGE and electrospray mass spectrometry.

Crystallization

Crystallization trials were carried out at 19°C, in hanging drops by vapour diffusion (linbro-plates), with a 1:1 ratio of protein (concentration: 5–9 mg/ml) to precipitant. After purification, pro-ADC was subjected to crystallization in 1.6 M (NH4)2SO4. S25A crystallized in 1.5 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.15 M Tris–HCl pH 8.0, A24a-G24b, G24S, H11A, S25a-A25b, and S25C crystallized in 1.4–1.6 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 M citric acid pH 4.0. Crystals grew within 7 days, up to a size of 0.6 × 0.6 × 1 mm, and were successively incubated for 3–5 min in mother liquor solutions with 1, 5, 10 15, 20 and 25% (v/v) glycerol. S25T was crystallized in 2.4 M sodium malonate, NaOH pH 4.0 and cryo-protected by gradually increasing the sodium malonate concentration to 3.2 M.

Data collection and data processing

Crystals were mounted in cryo-loops (Hampton Research) and frozen in liquid N2. Diffraction data for pro-ADC, S25A, S25C and A24a-G24b, S25a-A25b, G24S, H11A and S25T were collected in house with a Cu rotating anode generator and RAXIS IV image plate (Rigaku MSC) and at Daresbury SRS stations 14.1 and 14.2 with a Q4 ADSC-CCD, respectively. Diffraction data were indexed with DENZOv1.97.2 (Otwinowski, 1991) and intensities scaled with SCALEPACKv.1.97.2 (Otwinowski, 1991). Data conversion into structure factor amplitudes and all data manipulation were performed with programs of the CCP4-suitev4.2.1 (Collaborative Computational Project, 1994).

Structure solution and refinement

Pro-ADC and all ADC mutants, except S25A, crystallized in space group P6122 as observed previously (Albert et al., 1998). S25A formed crystals in space group I422. The structures were solved by isomorphous replacement and molecular replacement with AMORE (Navaza, 2001) with the processed ADC structure as a search model. Rigid-body refinement and simulated annealing in CNSv1.1 (Brunger et al., 1998) were followed by restrained, isotropic refinement with REFMACv5.1.24 (Murshudov et al., 1999). A 5% test set of randomly selected reflections was used for calculation of Rfree (Brunger, 1992). Manual rebuilding cycles were performed in O (Jones et al., 1991) and Xfit (McRee, 1999). Residues 19–25 were omitted from initial refinement and built into σA weighted mFo–DFc maps. Parameters for malonate, sulfate and sodium ion were retrieved from the Uppsala HIC-Up server (Kleywegt and Jones, 1998). In the last refinement stages TLS refinement (Winn et al., 2001) was applied to improve the data fit. The TLS groups were defined according to secondary structure, the number varying depending on the diffraction data quality, and TLS parameters evaluated with TLSANL (Howlin et al., 1993). Refinement was continued until convergence of the Rfree.

Model analysis

Protein models were evaluated with RAMPAGE (Lovell et al., 2003) and WHATCHECK (Hooft et al., 1996). Structural superposition and r.m.s.d. calculations were carried out with LSQMAN (Kleywegt and Jones, 1994).

Accession numbers

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the ID codes 1ppy (pro-ADC), 1pyq (A24a-G24b), 1pqf (G24S), 1pt1 (H11A), 1pt0 (S25a-A25b), 1pqe (S25A), 1pyu (S25C) and 1pqh (S25T).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Paul de Bakker for helpful advice and Martyn Symmons for critical reading of the manuscript. Funding from the University of Vienna, the Cambridge European Trust, CCT, ORS, the Skye Foundation, the University of Cape Town, BBSRC, Astex Technology and the EPSRC is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Albert A. et al. (1998) Crystal structure of aspartate decarboxylase at 2.2 Å resolution provides evidence for an ester in protein self-processing. Nat. Struct. Biol., 5, 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarski B., Andreesen,J.R. and Pich,A. (2001) In vitro processing of the proproteins GrdE of protein B of glycine reductase and PrdA of d-proline reductase from Clostridium sticklandii: formation of a pyruvoyl group from a cysteine residue. Eur. J. Biochem., 268, 3538–3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannigan J.A., Dodson,G., Duggleby,H.J., Moody,P.C., Smith,J.L., Tomchick,D.R. and Murzin,A.G. (1995) A protein catalytic framework with an N-terminal nucleophile is capable of self-activation. Nature, 378, 416–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger A.T. (1992) The R-free value: a novel statistical quality for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature, 335, 472–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger A.T. et al. (1998) Crystallography and NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D, 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project. (1994) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D, 50, 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan J.E. Jr (1980) β-Alanine synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 141, 1291–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano W.L. (2002) The PyMOL molecular graphics system. http://www.pymol.org.

- Ditzel L., Huber,R., Mann,K., Heinemeyer,W., Wolf,D.H. and Groll,M. (1998) Conformational constraints for protein self-cleavage in the proteasome. J. Mol. Biol., 279, 1187–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X., Gimble,F.S. and Quiocho,F.A. (1997) Crystal structure of PI-SceI, a homing endonuclease with protein splicing activity. Cell, 89, 555–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggleby H.J., Tolley,S.P., Hill,C.P., Dodson,E.J., Dodson,G. and Moody,P.C. (1995) Penicillin acylase has a single-amino-acid catalytic centre. Nature, 373, 264–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom J.L., Mathews,I.I., Stanley,B.A., Pegg,A.E. and Ealick,S.E. (1999) The crystal structure of human S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase at 2.25 Å resolution reveals a novel fold. Structure Fold. Des., 7, 583–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom J.L., Tolbert,W.D., Xiong,H., Pegg,A.E. and Ealick,S.E. (2001) Structure of a human S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase self-processing ester intermediate and mechanism of putrescine stimulation of processing as revealed by the H243A mutant. Biochemistry, 40, 9495–9504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher T., Rozwarski,D.A., Ernst,S.R. and Hackert,M.L. (1993) Refined structure of the pyruvoyl-dependent histidine decarboxylase from Lactobacillus 30a. J. Mol. Biol., 230, 516–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan C., Cui,T., Rao,V., Liao,W., Benner,J., Lin,C.L. and Comb,D. (1996) Activation of glycosylasparaginase. Formation of active N-terminal threonine by intramolecular autoproteolysis. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 1732–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H.C., Xu,Q., Buckley,D. and Guan,C. (1998) Crystal structures of Flavobacterium glycosylasparaginase. An N-terminal nucleophile hydrolase activated by intramolecular proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 20205–20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T.M., Porter,J.A., Young,K.E., Koonin,E.V., Beachy,P.A. and Leahy,D.J. (1997) Crystal structure of a Hedgehog autoprocessing domain: homology between Hedgehog and self-splicing proteins. Cell, 91, 85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooft R.W., Vriend,G., Sander,C. and Abola,E.E. (1996) Errors in protein structures. Nature, 381, 272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin B., Moss,D.S., Harris,G.W. and Driessen,H.P.C. (1993) TLSANL:TLS parameter-analysis program for segmented anisotropic refinement of macromolecular structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 26, 622–624. [Google Scholar]

- Isupov M.N., Obmolova,G., Butterworth,S., Badet-Denisot,M.A., Badet,B., Polikarpov,I., Littlechild,J.A. and Teplyakov,A. (1996) Substrate binding is required for assembly of the active conformation of the catalytic site in Ntn amidotransferases: evidence from the 1.8 Å crystal structure of the glutaminase domain of glucosamine 6-phosphate synthase. Structure, 4, 801–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zou,J.Y., Cowan,S.W. and Kjeldgaard. (1991) Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A, 47, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.K., Yang,I.S., Rhee,S., Dauter,Z., Lee,Y.S., Park,S.S. and Kim,K.H. (2003) Crystal structures of glutaryl 7-aminocephalosporanic acid acylase: insight into autoproteolytic activation. Biochemistry, 42, 4084–4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Yoon,K., Khang,Y., Turley,S. and Hol,W.G. (2000) The 2.0 Å crystal structure of cephalosporin acylase. Structure Fold. Des., 8, 1059–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Kim,S., Earnest,T.N. and Hol,W.G. (2002) Precursor structure of cephalosporin acylase. Insights into autoproteolytic activation in a new N-terminal hydrolase family. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 2823–2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klabunde T., Sharma,S., Telenti,A., Jacobs,W.R.,Jr and Sacchettini,J.C. (1998) Crystal structure of GyrA intein from Mycobacterium xenopi reveals structural basis of protein splicing. Nat. Struct. Biol., 5, 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt G.J. and Jones,T.A. (1994) A super position. CCP4/ESF-EACBM Newsletter on Protein Crystallography, 31, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt G.J. and Jones,T.A. (1998) Databases in protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D, 54, 1119–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis P.J. (1991) MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 24, 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon A., Lee,B., Han,B.W., Ahn,H.J., Yang,J.K., Yoon,H. and Suh,S.W. (2002) Crystallization and preliminary x-ray crystallographic analysis of aspartate 1-decarboxylase from Helicobacter pylori. Acta Crystallogr. D, 58, 861–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell S.C., Davis,I.W., Arendall,W.B.,3rd, De Bakker,P.I., Word,J.M., Prisant,M.G., Richardson,J.S. and Richardson,D.C. (2003) Structure validation by Cα geometry: φ, ψ and Cβ deviation. Proteins, 50, 437–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J., Stock,D., Jap,B., Zwickl,P., Baumeister,W. and Huber,R. (1995) Crystal structure of the 20S proteasome from the archaeon T. acidophilum at 3.4 Å resolution. Science, 268, 533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRee D.E. (1999) A versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density. J. Struct. Biol., 125, 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt E.A. and Bacon,D.J. (1997) Raster3D: Photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol., 277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi K., Deane,C.M., Blundell,T.L., Johnson,M.S. and Overington,J.P. (1998) JOY: protein sequence–structure representation and analysis. Bioinformatics, 14, 617–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani R., Nogami,S., Kawasaki,M., Ohya,Y., Anraku,Y. and Satow,Y. (2002) Protein-splicing reaction via a thiazolidine intermediate: crystal structure of the VMA1-derived endonuclease bearing the N and C-terminal propeptides. J. Mol. Biol., 316, 919–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G.N., Vagin,A.A. and Dodson,E.J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D, 53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G.N., Vagin,A.A., Lebedev,A., Wilson,K.S. and Dodson,E.J. (1999) Efficient anisotropic refinement of macromolecular structures using FFT. Acta Crystallogr. D, 55, 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaza J. (2001) Implementation of molecular replacement in AMoRe. Acta Crystallogr. D, 57, 1367–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oinonen C., Tikkanen,R., Rouvinen,J. and Peltonen,L. (1995) Three-dimensional structure of human lysosomal aspartylglucosaminidase. Nat. Struct. Biol., 2, 1102–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. (1991) Processing of X-ray diffraction data in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol., 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus H. (2000) Protein splicing and related forms of protein autoprocessing. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 69, 447–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poland B.W., Xu,M.Q. and Quiocho,F.A. (2000) Structural insights into the protein splicing mechanism of PI-SceI. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 16408–16413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramjee M.K., Genschel,U., Abell,C. and Smith,A.G. (1997) Escherichia colil-aspartate-α-decarboxylase: preprotein processing and observation of reaction intermediates by electrospray mass spectrometry. Biochem. J., 323, 661–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recsei P.A., Huynh,Q.K. and Snell,E.E. (1983) Conversion of prohistidine decarboxylase to histidine decarboxylase: peptide chain cleavage by nonhydrolytic serinolysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 80, 973–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Schagger H. and Von Jagow,G. (1987) Tricine–sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem., 166, 368–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemuller E., Lupas,A. and Baumeister,W. (1996) Autocatalytic processing of the 20S proteasome. Nature, 382, 468–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.L., Zaluzec,E.J., Wery,J.P., Niu,L., Switzer,R.L., Zalkin,H. and Satow,Y. (1994) Structure of the allosteric regulatory enzyme of purine biosynthesis. Science, 264, 1427–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert W.D., Graham,D.E., White,R.H. and Ealick,S.E. (2003a) Pyruvoyl-dependent arginine decarboxylase from Methanococcus jannaschii. Crystal structures of the self-cleaved and S53A proenzyme forms. Structure (Camb.), 11, 285–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert W.D., Zhang,Y., Cottet,S.E., Bennett,E.M., Ekstrom,J.L., Pegg,A.E. and Ealick,S.E. (2003b) Mechanism of human S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase proenzyme processing as revealed by the structure of the S68A mutant. Biochemistry, 42, 2386–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Poelje P.D. and Snell,E.E. (1990) Pyruvoyl-dependent enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 59, 29–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderslice P., Copeland,W.C. and Robertus,J.D. (1988) Site-directed alteration of serine 82 causes nonproductive chain cleavage in prohistidine decarboxylase. J. Biol. Chem., 263, 10583–10586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn M.D., Isupov,M.N. and Murshudov,G.N. (2001) Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D, 57, 122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H. and Pegg,A.E. (1999) Mechanistic studies of the processing of human S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase proenzyme. Isolation of an ester intermediate. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 35059–35066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H., Stanley,B.A., Tekwani,B.L. and Pegg,A.E. (1997) Processing of mammalian and plant S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase proenzymes. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 28342–28348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H., Stanley,B.A. and Pegg,A.E. (1999) Role of cysteine-82 in the catalytic mechanism of human S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase. Biochemistry, 38, 2462–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q., Buckley,D., Guan,C. and Guo,H.C. (1999) Structural insights into the mechanism of intramolecular proteolysis. Cell, 98, 651–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]