Abstract

Obesity and smoking represent the leading preventable causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States. This study compared the prevalence of obesity among smokers seeking cessation treatment (n = 1428) versus a general population (n = 4081) of never smokers, former smoker, and current smokers. Data from treatment-seeking smokers in the Wisconsin Smokers’ Health Study (WSHS) and individuals who completed the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005-06 were pooled and obesity rates and other health characteristics were compared. The prevalence of obesity was significantly higher among WSHS treatment-seeking smokers (36.8%) versus NHANES current smokers (29.6%), but the obesity rates of WSHS treatment-seeking smokers did not differ from NHANES former smokers (36.5%) or never smokers (36.5%). Treatment-seeking smokers were more likely to be female and to have higher educational attainment compared to NHANES participants. Analysis of health characteristics revealed treatment-seeking smokers had higher levels of dietary fiber and vitamin C and lower blood levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting glucose compared to NHANES current smokers. Results suggest that treatment-seeking smokers may have a different health profile than current smokers in the general population. Health care providers should be aware of underlying heath issues, particularly obesity, in patients seeking smoking cessation treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity and smoking are the leading preventable causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States (1). In fact, an overweight smoker’s life expectancy is, on average, 13 years shorter than a normal weight nonsmoker’s life expectancy (2). The associations between obesity and smoking are complex. In general, smoking is associated with lower body weight (3–6). It is hypothesized that smoking lowers body weight set point (7), which leads to increased energy expenditure until the nicotine-induced set-point is achieved (8). In addition, smoking generally extends satiety, which may decrease between-meal snacking and caloric intake (7). An alternative hypothesis is that smoking delays the usual age-related weight gain (9, 10). Smokers’ body weight also may vary depending on frequency of smoking and socioeconomic status. It has been shown that individuals who smoke heavily are typically more overweight than light smokers (11–13) and lower socioeconomic status is associated with increased likelihood of being overweight (14). Finally, while on-going smoking may be related to lower body weight, smoking cessation is often followed by weight gain (3, 15).

To our knowledge, this is the first report to compare the prevalence of obesity in smokers seeking treatment as part of a smoking cessation trial with a general population sample of never smokers, former smokers, and current smokers. This will illuminate whether the most at-risk smokers, those with comorbid obesity, are especially likely, or unlikely, to volunteer for cessation treatment. In addition, it is important to characterize the nature of the risk posed by the concurrent risk factors of obesity and smoking. Therefore, the purpose of this report is to compare the prevalence of obesity and other health characteristics among treatment-seeking smokers using participants in the Wisconsin Smokers’ Health Study (WSHS), with a general population of smokers participating in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005-06.

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

1,428 subjects with complete baseline body mass index (BMI), smoking, and demographic characteristics from the WSHS were selected from the study’s total sample of 1,504 smokers. These individuals, ages 20 to 85, are currently completing the follow-up segment of a smoking cessation clinical trial conducted in Madison and Milwaukee, WI, that began in 2005. Adult smokers were recruited via TV, radio and newspaper advertisements, flyers, earned media including press conferences, and TV and radio news interviews. Inclusion criteria included smoking greater than 9 cigarettes per day on average for at least the past 6 months and being motivated to quit smoking. Exclusion criteria included using any non-cigarette form of tobacco, currently taking bupropion, medical contraindications for any of the study medications (Bupropion, Nicotine Patch, or Nicotine Lozenge), high alcohol consumption (6 drinks per day on 6 or 7 days of the week), history of seizure, schizophrenia, psychosis, bipolar disorder, an eating disorder, a recent cardiac event, or allergies to the medications. For additional details, see Piper et al (under review) (16).

To compare treatment-seeking smokers with a general population of smokers, we selected participants, age 20 or older, from the NHANES 2005-06 dataset. The NHANES 2005-06 is a complex, multistage probability sample of the non-institutionalized population of the United States. Certain population sub-groups were oversampled, including adolescents aged 12–19 years, African Americans, and Mexican Americans, to allow for precise estimates from each group. From the NHANES sample with complete data for BMI, smoking, and demographic characteristics (n = 4,081), we identified three classes of smokers: never smokers (n = 2,371), former smokers (n = 1,122) and current smokers (n = 588, defined as smoking greater than 10 cigarettes per day). Thus the combined NHANES and WSHS final sample (n = 5,509) included 4,081 individuals (never, former, and current smokers) from the NHANES sample and 1,428 treatment-seeking smokers from the WSHS sample.

For both the WSHS and the NHANES samples, BMI was calculated using participants’ clinically measured weight and height (kg/m2). A BMI of < 18.5 was classified as underweight, a BMI of 18.5–24.9 was classified as normal weight, a BMI of 25.0–29.9 as overweight, and a BMI of 30.0 or greater as obese (17). Seventy-seven participants were classified as underweight. Because these individuals made up a small proportion of the total sample (1.4%), we combined these individuals with the normal weight category.

In addition to BMI, we used demographic, dietary, blood lipids and glucose, and smoking behavior variables collected from the WSHS and NHANES to further compare health characteristics among the groups of smokers.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), where standard descriptive statistics (mean or %) were used to describe demographic, physical and lifestyle variables. For significance testing, chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables and general linear models were used for continuous variables. An α of 0.05 was used to identify significant differences between treatment-seeking smokers, current smokers, former smokers, and never smokers. This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Human Subjects Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

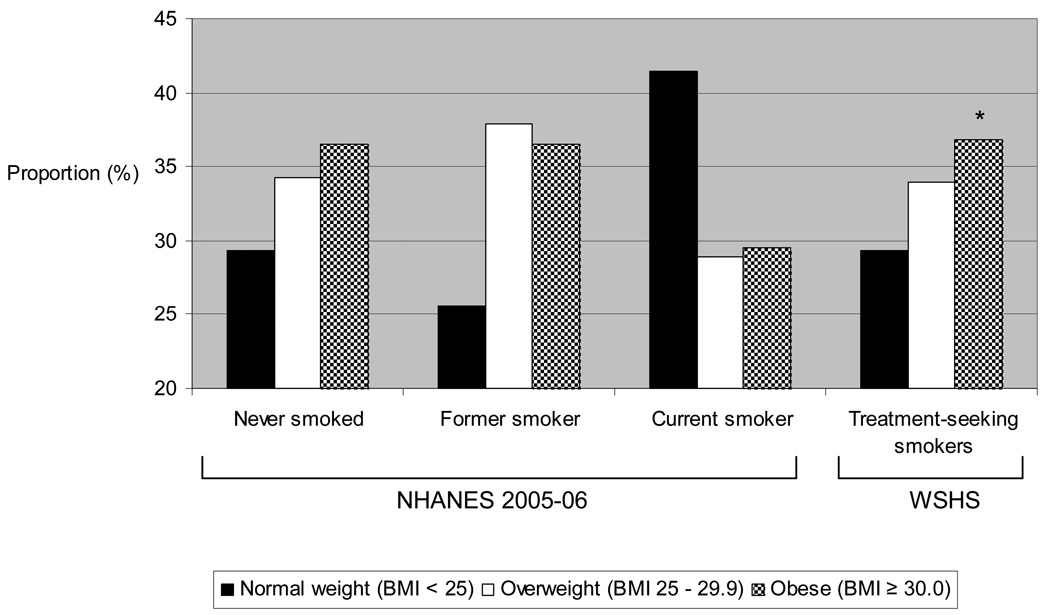

Figure 1 shows that obesity was significantly more prevalent among treatment-seeking smokers in the WSHS than current smokers in the general population (36.8% vs. 29.6%, p < 0.0001). Combined overweight/obesity rates in treatment-seeking smokers were similar to NHANES never smokers (70.7% and 70.8% respectively), while NHANES former smokers had the highest rates (74.4%) and NHANES current smokers had the lowest rates (58.5%).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of overweight and obesity in never, former, and current smokers among participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005-06 and treatment-seeking smokers in the Wisconsin Smokers’ Health Study (WSHS). Obesity was significantly more common among higher WSHS treatment-seeking smokers than among NHANES current smokers (p < 0.0001).

Table 1 shows selected demographic, smoking, diet, and biochemical characteristics among smokers in the WSHS and NHANES samples. The majority of treatment-seeking smokers was white/Caucasian (84%) and had a higher educational attainment than the NHANES sample. Data on smoking behaviors revealed that treatment-seeking smokers were similar to current smokers in their time to first cigarette after waking, but tended to smoke more heavily than current smokers in the NHANES sample (> 21 cigarettes/day: 39.7% vs. 22.5%, p < 0.0001). Current smokers in the NHANES sample, compared to treatment-seeking smokers, had lower intakes of dietary fiber (13.1 mg/day vs. 15.9 mg/day, p < 0.05) and vitamin C (70.2 mg/day vs. 87.5 mg/day, p < 0.05), both markers of fruit and vegetable intake, and higher blood levels of total cholesterol (202.5 mg/dL vs. 183.8 mg/dL, p < 0.05) and triglycerides (158.0 mg/dL vs. 142.2 mg/dL, p < 0.05). Treatment-seeking smokers had lower fasting glucose levels and HDL cholesterol levels than any of the groups in the NHANES sample.

Table 1.

Selected demographic, smoking, and health characteristics by smoking status in adults participating in the NHANES 2005-06 and WSHS.

| NHANES 2005-06 | WSHS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Never smokers (n=2,371) |

Former smokers (n=1,122) |

Current smokers (n=588) |

Treatment- seeking smokers (n=1,428) |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 45.1 ± 18.52 | 55.8 ± 18.6 1 | 44.5 ± 15.3 2 | 44.8 ± 11.0 2 |

| Gender (% female) | 61.7 | 41.3 | 43.2 | 58.41 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 42.8 | 61.8 | 66.7 | 84.01 |

| African American | 24.7 | 16.7 | 20.2 | 13.6 |

| Hispanic and Other | 32.5 | 21.7 | 13.1 | 2.5 |

| Education (%) | ||||

| < 12 years | 25.3 | 24.9 | 31.3 | 28.81 |

| 12 years | 21.8 | 23.9 | 32.1 | 23.2 |

| ≥ 12 years | 52.9 | 51.2 | 36.6 | 71.2 |

| Smoking Behaviors | ||||

| Time to smoke after waking (%) |

||||

| ≤ 5 minutes | -- | -- | 38.3 | 30.1 |

| 6–30 minutes | -- | -- | 34.5 | 46.7 |

| 31–60 minutes | -- | -- | 17.8 | 16.3 |

| > 60 minutes | -- | -- | 9.7 | 6.8 |

| Cigarettes smoke/day (%) | ||||

| ≤ 10 | -- | -- | 24.9 | 5.91 |

| 11–20 | -- | -- | 53.1 | 54.3 |

| 21–30 | -- | -- | 12.6 | 27.8 |

| > 30 | -- | -- | 9.9 | 11.9 |

| Diet Behaviors (mean ± SD) | ||||

| Energy (kcals) | 2021 ± 8162 | 2082 ± 807 2 | 2301 ± 977 1 | 1997 ± 879 2 |

| Fat (% energy) | 32.8 ± 7.52 | 34.0 ± 7.5 1 | 33.8 ± 8.0 1 | 34.4 ± 6.8 1 |

| Saturated fat (% energy) | 10.7 ± 3.23 | 11.2 ± 3.2 2 | 11.6 ± 3.5 1 | 11.8 ± 2.6 1 |

| Fiber (mg) | 16.4 ± 8.6 1 | 16.8 ± 8.1 1 | 13.1 ± 7.8 2 | 15.9 ± 8.3 1 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 98.2 ± 84.6 1 | 95.8 ± 78.0 1,2 | 70.2 ± 78.2 3 | 87.5 ± 65.8 2 |

| Alcohol (g) | 4.9 ± 14.5 3 | 8.7 ± 18.3 2 | 16.8 ± 32.1 1 | 8.5 ± 13.4 2 |

| Biochemical (mean ± SD) | ||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 200.3 ± 42.61,2 | 197.7 ± 44.3 2 | 202.5 ± 46.41 | 183.8 ± 35.53 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 135.6 ± 96.8 3 | 152.1 ± 110.21,2 | 158.0 ± 153.31 | 142.2 ± 98.02,3 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 56.1 ± 16.9 1 | 54.9 ± 16.21 | 52.8 ± 17.8 2 | 42.1 ± 13.5 3 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 115.9 ± 35.61,2 | 112.5 ± 37.32 | 118.4 ± 39.51 | 118.7 ± 30.41 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 103.4 ± 33.3 2 | 108.3 ± 33.1 1 | 102.3 ± 31.32 | 94.9 ± 17.9 3 |

NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; WSHS, Wisconsin Smokers’ Health Study; SD, standard deviation.

For continuous variables, values in the same row with different superscript numbers are significantly different, p <0.05 (Tukey-Kramer adjustment for multiple comparisons). For categorical variables, superscript number 1 represents significance of p <0.0001 on basis of chi-square comparisons.

DISCUSSION

We found that treatment-seeking smokers were significantly more likely to be obese than current smokers in a general population sample. In addition, these treatment-seeking smokers reported healthier dietary behavior and lower-risk lipid and glucose profiles than current smokers in the NHANES general population sample of smokers. Finally, current smokers in the NHANES general population sample had the lowest combined rates of overweight/obesity compared to never smokers, former smokers and treatment-seeking smokers. Data from current smokers in the NHANES sample support the finding that smokers tend to have lower body weight than nonsmokers, possibly due to differences in body weight set points (3–7). We had originally anticipated a similar finding among treatment-seeking smokers, but this was not the case. One possible explanation for why the sample of treatment-seeking smokers was actually more obese than the sample of current smokers is that the treatment-seeking sample was drawn from smokers living in Wisconsin. This regional sample may have higher obesity rates in general than national estimates. However, this explanation is unlikely because the 2005 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) found that obesity rates for Wisconsin are similar to the national rates (24.4%)(18).

One last possible explanation involves the current study’s finding that the treatment-seeking smokers smoked at a heavier rate than the current smokers in the general population. It may be that individuals who smoke at a higher rate (i.e. smoke more cigarettes per day) are more likely to seek cessation treatment due to their inability to quit (19, 20). In addition, individuals who smoke more may be more overweight (11–13), possibly due to weight cycling (21–23) from previous quit attempts (24).

In the present study, current NHANES smokers appeared to have poorer lifestyle behaviors than never smokers, former smokers and treatment-seeking smokers. This finding was expected, as risk behaviors (low intake of fruits and vegetables, low physical activity, and high alcohol consumption) typically cluster together in smokers (25). However, this trend was not found in treatment-seeking smokers who appeared to have healthier diet habits than current smokers. Treatment-seeking smokers may not only be motivated to quit smoking, but may also be more likely to adopt other healthy behaviors. This possibility is supported from our data which show that treatment-seeking smokers have higher intakes of vitamin C and fiber, and lower levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting glucose compared to current smokers in the general population, which may reflect healthier eating.

This study should be interpreted with certain caveats. First, we compared a national sample (the NHANES) with a regional sample (the WSHS), and differences in the ethnic composition of the two samples may have affected our results. The representation of African Americans, Hispanics and other ethnicities was lower in the WSHS sample than in the NHANES sample, and therefore, care should be taken in extrapolating the findings for the WSHS sample, beyond white treatment-seeking smokers. Second, this study only examined dependent smokers who smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day. This inclusion criteria may have resulted in an under-representation of African-American smokers in both samples because African-American smokers often smoke relatively few cigarettes per day (26, 27). Finally, the higher prevalence of obesity among the WSHS treatment-seeking smokers, than among the NHANES current smokers could reflect that smokers willing to participate in cessation trials, in which they are compensated for their time, may have certain characteristics (such as low socioeconomic status) associated with negative health outcomes, such as obesity. However, in a recent study, lifetime characteristics such as socioeconomic status, education, and ethnicity were similar between smokers who participated in a smoking cessation trial and those who did not (28).

In conclusion, we found that treatment-seeking smokers are more likely to be obese compared to a general population of smokers. Our data further revealed that despite the increased health risks due to obesity, treatment-seeking smokers had healthier dietary habits and better blood lipid profiles and blood glucose control than current smokers in the general population, possibly due to making other lifestyle changes, in addition to seeking smoking cessation treatment. Health care professionals should be aware that patients seeking smoking cessation treatments may be at particular risk for obesity related outcomes and providing patients with weight management or interventions after cessation treatment may be important.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is supported by an NIH Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center Grant #5P50DA019706. Dr. LaRowe was supported by an NIH National Research Service Award #T32-HP-10010-10 and Dr. Piper was supported by an Institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award (UW-Madison; KL2 Grant # 1KL2RR025012-01).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

TL LaRowe, ME Piper, TR Schlam, MC Fiore and TB Baker declared no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

TL LaRowe, School of Medicine and Public Health and Department of Family Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

ME Piper, School of Medicine and Public Health and Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

TR Schlam, School of Medicine and Public Health and Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

MC Fiore, School of Medicine and Public Health and Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

TB Baker, School of Medicine and Public Health and Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual Causes of Death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, et al. Obesity in Adulthood and Its Consequences for Life Expectancy: A Life-Table Analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:24–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson D, Madans J, Anda R, Kleinman J, Giovino G, Byers T. Smoking cessation and severity of weight gain in a national cohort. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:739–745. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103143241106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimokata H, Muller D, Andres R. Studies in the distribution of body fat. III. Effects of cigarette smoking. JAMA. 1989;261:1169–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flegal KM, Troiano RP, Pamuk ER, Kuczmarski RJ, Campbell SM. The Influence of Smoking Cessation on the Prevalence of Overweight in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1165–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huot I, Paradis G, Ledoux M. Factors associated with overweight and obesity in Quebec adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:766–774. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkins-Porras L, Cappuccio FP, Rink E, Hilton S, McKay C, Steptoe A. Does the effect of behavioral counseling on fruit and vegetable intake vary with stage of readiness to change? Preventive Medicine. 2005;40:314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofstetter A, Schutz Y, Jequier E, Wahren J. Increased 24-hour energy expenditure in cigarette smokers. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:79–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198601093140204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasmussen F, Tynelius P, Kark M. Importance of smoking habits for longitudinal and age-matched changes in body mass index: a cohort study of Swedish men and women. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klesges RC, Ray JW, Jacobs DR, Cutter G, Wagenknecht LE. The prospective relationships between smoking and weight in a young, biracial cohort: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:987–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bamia C, Trichopoulou A, Lenas D, Trichopoulos D. Tobacco smoking in relation to body fat mass and distribution in a general population sample. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1091–1096. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.John U, Hanke M, Rumpf HJ, Thyrian JR. Smoking status, cigarettes per day, and their relationship to overweight and obesity among former and current smokers in a national adult general population sample. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2005;29:1289–1294. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiolero A, Jacot-Sadowski I, Faeh D, Paccaud F, Cornuz J. Association of Cigarettes Smoked Daily with Obesity in a General Adult Population[ast] Obesity. 2007;15:1311–1318. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wild SH, Byrne CD. Risk factors for diabetes and coronary heart disease. BMJ. 2006;333:1009–1011. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39024.568738.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward K, Klesges R, Vander Wag M. Cessation of smoking and body weight. In: Bjorntop P, editor. International textbook of obesity. Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2001. pp. 323–336. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piper ME, Smith SS, Schlam TR, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of five smoking cessation pharmacotherapies. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.142. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Geneva: World Health Organization; WHO Technical Report Series 854. 1995 [PubMed]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of Smoking-Cessation Treatments in the United States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Twardella D, Loew M, Rothenbacher D, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. The impact of body weight on smoking cessation in German adults. Preventive Medicine. 2006;42:109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lissner L, Odell P, D'Agostino R, et al. Variability of body weight and health outcomes in the Framingham population. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1839–1844. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106273242602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroke A, Liese A, Schulz M, et al. Recent weight changes and weight cycling as predictors of subsequent two year weight change in a middle-aged cohort. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:403–409. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saarni SE, Rissanen A, Sarna S, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J. Weight cycling of athletes and subsequent weight gain in middleage. Int J Obes. 2006;30:1639–1644. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filozof C, Fernández Pinilla M, Fernández-Cruz A. Smoking cessation and weight gain. Obesity Reviews. 2004;5:95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiolero A, Wietlisbach V, Ruffieux C, Paccaud F, Cornuz J. Clustering of risk behaviors with cigarette consumption: A population-based survey. Preventive Medicine. 2006;42:348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giovino G, Schooley M, Zhu B, et al. Surveillance for selected tobacco-use behaviors--United States, 1900–1994. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1994;43:1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kabat GC, Morabia A, Wynder EL. Comparison of smoking habits of blacks and whites in a case-control study. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:1483–1486. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graham A, Papandonatos G, DePue J, et al. Lifetime characteristics of participants and non-participants in a smoking cessation trial: implications for external validity and public health impact. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:295–307. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9031-1. Epub 2008 Apr 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]