Abstract

There is evidence that HMGB proteins facilitate, while linker histones inhibit chromatin remodelling, respectively. We have examined the effects of HMG-D and histone H1/H5 on accessibility of nucleosomal DNA. Using the 601.2 nucleosome positioning sequence designed by Widom and colleagues we assembled nucleosomes in vitro and probed DNA accessibility with restriction enzymes in the presence or absence of HMG-D and histone H1/H5. For HMG-D our results show increased digestion at two spatially adjacent sites, the dyad and one terminus of nucleosomal DNA. Elsewhere varying degrees of protection from digestion were observed. The C-terminal acidic tail of HMG-D is essential for this pattern of accessibility. Neither the HMG domain by itself nor in combination with the adjacent basic region is sufficient. Histone H1/H5 binding produces two sites of increased digestion on opposite faces of the nucleosome and decreased digestion at all other sites. Our results provide the first evidence of local changes in the accessibility of nucleosomal DNA upon separate interaction with two linker binding proteins.

INTRODUCTION

It is becoming increasingly clear that the organisation of chromatin has important roles in transcriptional regulation, replication and repair. The fundamental unit of chromatin, the nucleosome, consists of 147 bp of DNA, wrapped in 1.65 turns, around a core of histones (1). The addition of linker histones and non-histone chromosomal proteins, which bind to DNA between nucleosomes, provides further degrees of organisation.

Both the binding of transcription factors to wrapped nucleosomal DNA and the mobilisation of nucleosomes require that the histone–DNA contacts be at least transiently broken. Two possible mechanisms, not necessarily mutually exclusive, could account for the resulting increase in accessibility to DNA-binding proteins and remodelling enzymes. Widom and colleagues have proposed a model of ‘transient unwrapping’ of DNA from the surface of the nucleosome from either end, allowing a proportion of internal sites to be exposed for binding at any one time (2–5). This same model has been used to explain the mechanism of intrinsic nucleosome mobility (3). An alternative model proposes that local changes in histone–DNA contacts on the nucleosome would allow access to internal DNA sites, without the need for unwrapping. The binding of the NFκB protein to internal sites on the nucleosome would be consistent with such a mechanism (6).

Transient unwrapping provides a consistent explanation for the association of transcription factors with binding sites close to one of the ends of nucleosomal DNA (for example the binding of TFIIIA to the nucleosome formed on the Xenopus borealis somatic 5S rRNA gene) (7). However the major impediments to transcription factor binding are the histone–DNA contacts in the vicinity of the dyad (8). The disruption of these contacts by transient unwrapping would require the initial ordered disruption of all the contacts between the terminal contact and the central contacts. It might therefore be anticipated that any proteins that altered the accessibility of wrapped nucleosomal DNA would affect this parameter at or close to one or both DNA termini and also at the dyad. Two classes of abundant chromosomal proteins, the HMGB proteins and the linker histones, could fulfil these criteria. HMGB1 binds close to one edge of the nucleosome (9). The globular domain of one linker histone (H5) has been shown to bind to both one end of nucleosomal DNA and to the DNA at the dyad (10) while the basic C-terminus binds to both the entering and leaving linker DNA (11,12).

The HMGB proteins are a subclass of HMG proteins that contain a highly conserved domain, the HMG-box; examples include vertebrate HMGB1 and 2, Drosophila HMG-D and Z and yeast Nhp6a and b (13). The HMG-box is a DNA binding domain capable of introducing sharp bends in DNA. Proteins, including HMGB1, containing this domain have recently been linked to nucleosome remodelling. Thus HMG-box containing proteins are components of chromatin remodelling complexes (BAP111 in Drosophila Brahma, BAP57 in mammalian SWI/SNF) or are associated with such complexes (SSRP1 in FACT) (14–16). In addition HMGB1 has been shown to increase the rate of nucleosome sliding by the ISWI containing remodelling factor CHRAC and increase the affinity of ACF for nucleosomes (17). These complexes have been proposed to generate a loop of DNA at the edge of the nucleosome, which is propagated round the octamer surface, resulting in nucleosome sliding. HMGB proteins could lower the activation energy required to produce the DNA loop, by pre-bending DNA at the edge of the nucleosome (17,18). Furthermore, recent studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have found genetic interactions between Nhp6 and members of the SAGA histone acetyltransferase complex (19), the RSC chromatin remodelling complex (20) and yFACT (21). At high concentrations of Nhp6, yFACT has been shown to alter the accessibility of nucleosomal DNA to DNase I (22).

Studies on the role of linker binding proteins have been mostly biochemical. Histone H1 is thought to stabilise higher order folding of nucleosomal arrays; which is repressive to transcription (23–25). However H1 also inhibits enzymatically driven nucleosome mobility (26,27).

A clue to the role of HMGB proteins is found in the chromatin of preblastoderm embryos of Drosophila and Xenopus (28,29). During embryogenesis, one of the Drosophila counterparts of HMGB1/2, HMG-D, is highly abundant while H1 levels are undetectable. As development progresses H1 is produced and displaces HMG-D. This property is observable in vivo and in vitro (30). It is proposed that HMG-D competes with H1 for binding to chromatin substrates. A similar role has been postulated for Xenopus HMGB1 (31,32). In Drosophila embryogenesis this abundance of HMG-D correlates with rapid nuclear division cycles, a situation which could require high nucleosome mobility. In contrast, H1 association with chromatin is correlated with global transcriptional competence.

In this paper we have used an assay developed by Widom and colleagues (2,5) to examine the effect of HMG-D and H1 binding on exposure of nucleosomal DNA. We show that HMG-D binding induces local changes in DNA accessibility, resulting in a specific domain of exposed sites. These are located on one face of the nucleosome and encompass the entry point of DNA as well as the dyad. We find that the acidic C-terminal tail of HMG-D is required for this pattern of accessibility. H1 binding, however, results in the opposite pattern of accessibility to HMG-D, with the majority of sites becoming less accessible to restriction enzyme digestion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA fragments

The 174 bp fragment of 601.2 sequence was derived from plasmid pGEM-3Z and has been described (5). ClaI and EcoRI sites were introduced at the 5′ and 3′ end, respectively, using PCR. The 183 bp fragment was cloned into the pBlueScript® II SK– vector. The fragment was 32P-labelled with [α-32P]CTP at the 3′ end of the non-coding strand or [α-32P]ATP at the 3′ end of the coding strand using Klenow fragment. The 207 bp AvaI fragment, containing one copy of the sea urchin 5S rDNA sequence, was derived from p5S207-18 (33) and was labelled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase.

Protein expression and purification

Recombinant HMG-D, HMG-D100 and HMG-D74 were expressed and purified as previously described (34,35). Native chicken H1/H5 was a gift of Philip Robinson and recombinant HMGB1 was a gift of Jean Thomas. Histone octamers were purified from chicken erythrocyte nuclei as previously described (36).

Nucleosome reconstitution

Nucleosomes were reconstituted at 4°C by gradual salt dialysis (37). Chicken erythrocyte core DNA and radiolabelled specific DNA were mixed at a molar ratio of 0.8:1 to purified histone octamer, in 2 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) and dialysed into a final buffer of 10 mM Tris–HCl, 0.1% NP-40. Reconstitutions were monitored by electrophoresis in 5% native polyacrylamide gels in 0.2× TBE. Gels were dried and exposed on phosphorimager screens.

Binding reactions and DNA accessibility assay

Aliquots of 40–50 fmol reconstituted nucleosomes (5–10 ng radiolabelled DNA) were incubated in 50 µl of binding buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 70 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM MgCl2). Final concentrations of protein required for stoichiometric binding to nucleosomes were: 0.05 µM for HMG-D, 0.025 µM for HMG-D100 and 0.5 µM for HMG-D74. Due to problems with aggregation, binding of H1 was performed at a final concentration of 20 nM, which resulted in half occupancy of nucleosomes. Binding reactions were incubated at 22°C for 15 min before digestion with restriction enzymes.

The restriction enzyme assay was conducted as described (2,5) with the following modifications. At various time points 10 µl aliquots were removed and quenched, on ice, by addition of an equal volume of stop buffer (7 M urea, 50 mM EDTA pH 7.4, 50% formamide). Samples were boiled for 5 min before being resolved on denaturing polyacrylamide gels, dried and quantified using a phosphorimager.

Two-dimensional gel experiments

The assays were conducted as previously described (32,33) with modifications. Labelled nucleosomes, reconstituted on the sea urchin 5S positioning sequence, in the absence or presence of 0.5 µM HMG-D, 40 nM H1/H5 or 0.4 µM HMGB1, were run on 8% native polyacrylamide gels in 0.2× TBE at 4°C. Gel lanes were excised, halved lengthwise, with half a lane incubated at 4°C and half at 37°C for 1 h, before electrophoresis in the second dimension at 4°C.

RESULTS

HMG-D causes local changes in restriction enzyme accessibility on the nucleosome

HMG-D is one of two abundant Drosophila HMGB proteins, containing a single HMG-box domain, followed by a stretch of basic residues and a highly acidic C-terminal tail. It binds with little sequence specificity, but has a preference for distorted DNA structures such as DNA bulges, cruciforms and pre-bent DNA (34,38). To determine whether HMG-D increases the accessibility of nucleosomal DNA on binding, we made use of the assay developed by Widom and colleagues (5). In this assay, the kinetics of restriction enzyme digestion are used to determine the accessibility of the DNA on positioned nucleosomes in vitro. Nucleosomes are reconstituted on the 601.2 sequence, a strong positioning sequence with unique restriction enzyme sites engineered at points along the sequence, to allow reproducible quantitation of the rate of digestion at individual sites (2). The output of the assay is a time course with the degree of digestion visible as uncut substrate and cleaved product. Widom et al. calculate equilibrium constants describing the ‘site exposure’ of the site by the ratio of the rate of digestion of nucleosomes to naked DNA. Anderson and Widom (2) showed that DNA at the ends of the nucleosome was more accessible than sites closer to the dyad. We have been unable to use this model directly, as the protein bound to certain restriction sites on naked DNA, inhibiting digestion. We assume that HMG-D is recognising intrinsic flexible DNA regions in the 601.2 sequence.

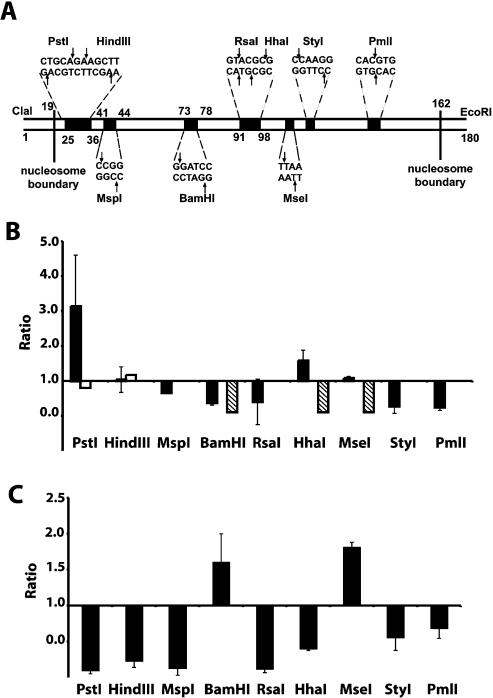

We modified the 601.2 sequence by adding ClaI and EcoRI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, increasing its size to 180 from 174 bp. The addition of these extra sites did not affect the positioning of the nucleosome but allowed the unique labelling of either strand, which was useful for DNase I and hydroxyl radical footprinting as well as decreasing the error in the restriction assay due to random end labelling. The positions of the restriction enzyme sites are shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

HMG-D and histone H1/H5 binding to nucleosomes induces changes in nucleosome structure. (A) Schematic of the restriction enzyme sites on nucleosomes reconstituted on the 601.2 sequence [adapted with permission from fig. 1A in Anderson et al. (3)]. (B) Means and standard deviations for the ratio of the rate of digestion of protein-bound nucleosomes to unbound nucleosomes are plotted as a function of the location on the nucleosome. Means are results of a least three independent assays. Full-length HMG-D, black bars; histone H1/H5, grey bars; HMG-D100, open bars and hatched bars. The hatched bars indicate sites at which HMG-D100 inhibits restriction enzyme digestion to the extent that no significant rate could be calculated. HMG-D74 (data not shown) has little or no effect on digestion. (C) Means and standard deviations as in (B) for H1/H5 bound versus unbound nucleosomes.

Reconstituted nucleosomes were digested with various restriction enzymes along the length of the 601.2 sequence. Parallel digests of nucleosomes in the absence or presence of HMG-D were also conducted. Before starting the digestion 30–50 fmol of nucleosomes were incubated at 22°C for 15 min with sufficient HMG-D to form a nucleosome–HMG-D complex. The necessary amount of HMG-D (2.5 pmol/assay or 0.05 µM) was determined empirically by band shift. However identical changes in DNA accessibility were also seen with the sub-saturating concentration of 0.025 µM HMG-D (data not shown).

The initial rates of digestion were obtained from exponential fits to plots of fraction uncut substrate versus time. Differences in the rates of digestion, due to HMG-D binding, are illustrated, in Figure 1B, as the ratio of rate of digestion of HMG-D bound versus unbound nucleosomes. We take an increased rate of digestion to be correlated with increased accessibility at a given site, which is illustrated as a ratio greater than 1.

HMG-D binding results in changes to DNA accessibility at all sites examined. There is an increased rate of digestion at one end of the nucleosome, at the PstI site (e.g. 7.41 × 10–5 to 3.28 × 10–4 s–1). Located at the dyad (Supplementary Material) the HhaI site is also exposed (e.g. 4.80 × 10–5 to 1.04 × 10–4 s–1) and to a lesser extent the MseI site (1.13 × 10–4 to 1.23 × 10–4 s–1) located further downstream. Interestingly the RsaI site, almost immediately adjacent to the HhaI site, has a decreased rate of digestion. HMG-D binding also results in decreased rates of digestion at other sites, notably the other end of the nucleosome, at the StyI and PmlI sites. This suggests that HMG-D binding induces local changes rather than an overall/global increase or decrease on the whole of the nucleosome. The pattern of accessibility is such that DNA is accessible at one end of the nucleosome and becomes progressively less accessible towards the dyad. There is a local area of exposure at the dyad, lost again at the furthest edge of the nucleosome.

To visualise the changes in accessibility in the context of the nucleosome, we have mapped the changes in accessibility to the crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle (Supplementary Material). This clearly shows the boundaries of the exposed domain. Restriction enzyme sites were mapped using positions assigned relative to the dyad and according to the pattern of hydroxyl radical cleavage (Supplementary Material).

The C-terminus of HMG-D is necessary for pattern of accessibility

HMG-D consists of three structural domains, the HMG-box DNA binding domain, the basic region adjacent to the box and a C-terminal acidic tail. Previous studies have examined the effects of truncation mutations on HMG-D binding affinity for DNA substrates. These mutants lack either the C-terminal tail (HMG-D100) or the both the tail and basic region (HMG-D74). In vitro studies found that removal of the tail of HMG-D has little effect on binding to DNA nor does it affect the nucleosome repeat length when reconstituted onto chromatin (30,34).

We have investigated whether the truncation mutants affected the pattern of accessibility observed with the full-length protein. In binding to nucleosomes the HMG-D74 mutant has the lowest affinity while HMG-D100 binds with higher affinity than the full-length protein (Materials and Methods). The effect of the HMG-D100 mutant on site accessibility was dramatically different from HMG-D (Fig. 1B). At sites close to the dyad digestion was completely inhibited, while other sites showed a decrease in rates of digestion. These are the same sites that were more exposed upon binding of the full-length protein. The HMG-D74 mutant, consisting only of the DNA binding domain, did not cause any changes in DNA accessibility at the sites examined (data not shown). We conclude that the HMG-box domain of HMG-D is not sufficient to induce the observed changes in accessibility and that the C-terminal tail is required to produce the specific pattern of accessibility seen upon HMG-D binding.

HMG-D does not move the 601.2 nucleosome

The increase in accessibility of certain restriction sites induced by HMG-D could in principle be a consequence of the nucleosome moving to a different translational position(s). To ask whether this was the case we first used hydroxyl radical and DNase I footprinting in the presence and absence of HMG-D. In agreement with previous findings (31), we observed that HMG-D did not affect the pattern of either hydroxyl radical or DNase I cleavage of 601.2 nucleosomal DNA (Supplementary Material). In addition, on HMG-D binding the dyad position remained the same, indicating that the nucleosome retained its original translational position during the cleavage reaction.

We also wished to test whether HMG-D could induce a shift in position over time periods comparable to the restriction assay. Nucleosomes have been shown to possess intrinsic mobility in vitro, moving through several translational positions when incubated at 37°C (39). This property has been exploited in assays studying the effect of histone H1 and HMGB1 binding to nucleosomes. It has been established that histone H1 inhibits mobility on mono- and dinucleosome substrates and HMGB1 has been shown to inhibit mobility on dinucleosomes (32,33,40).

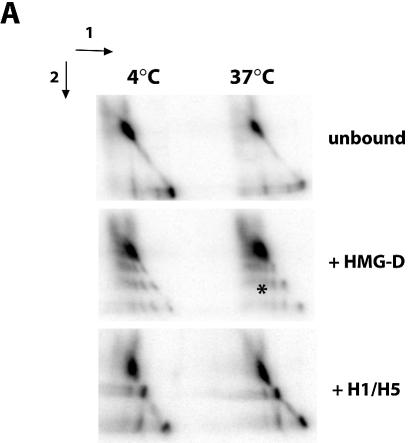

We asked whether the nucleosome containing the 601.2 positioning sequence was intrinsically mobile. Using the two-dimensional gel assay developed by Meerssemann et al. (39), in which nucleosomes were run on 8% polyacrylamide gels in one dimension at 4°C, incubated at 37°C, and run in the second dimension, we observed that this nucleosome remained in a single translational position, i.e. on the diagonal (Fig. 2A). Similarly, in the presence of H1/H5 or HMG-D, nucleosomes remained fixed in a single translational position. This is important for the restriction assay as it proves that nucleosomes reconstituted on the 601.2 sequence remain stable for the duration of the experiment.

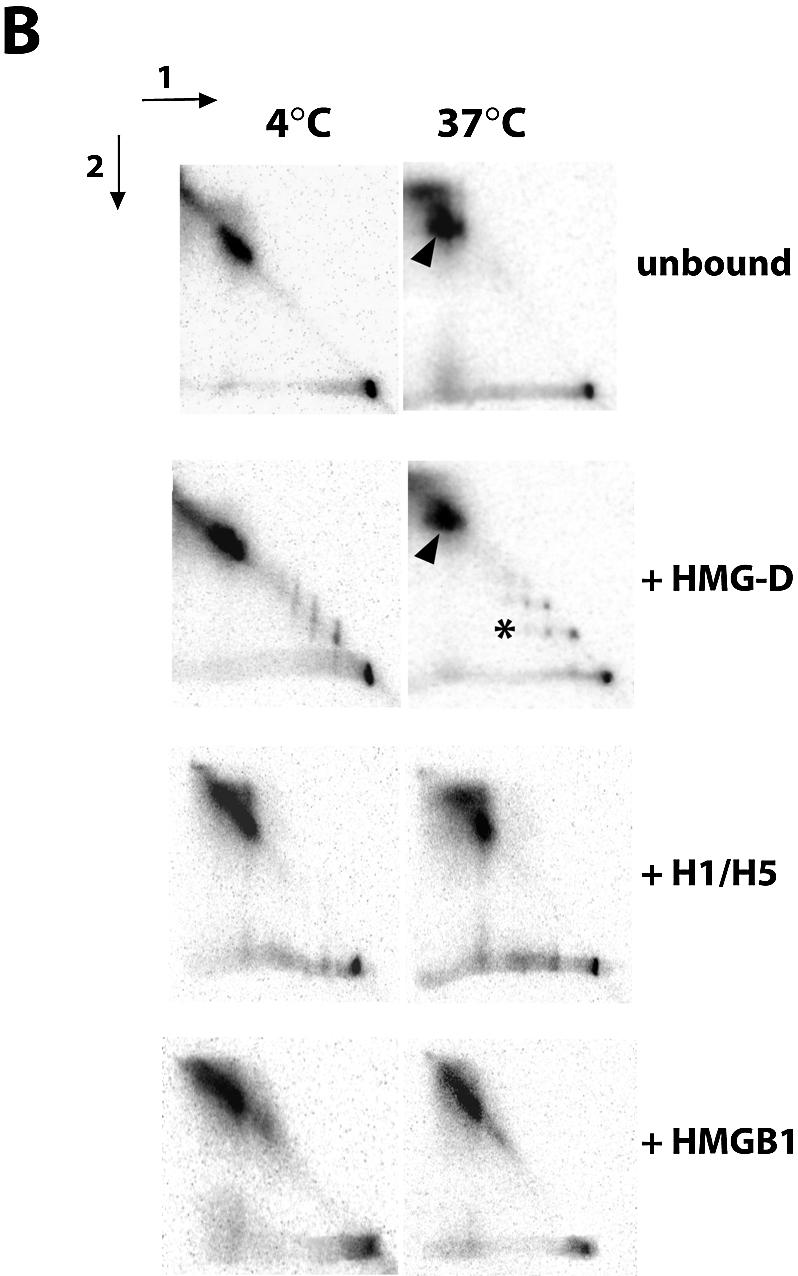

Figure 2.

(A) Nucleosomes reconstituted on the 601.2 positioning sequence do not have intrinsic mobility. Aliquots of 50 fmol of nucleosomes, reconstituted on the 601.2 sequence positioning sequence in the presence of 0.5 µM HMG-D, 40 nM histone H1/H5 or 0.4 µM HMGB1, were resolved on native 8% polyacrylamide gels at 4°C before incubation of half gel slices at 4 or 37°C for 1 h as indicated, followed by second dimension electrophoresis. Arrows indicate the directions of electrophoresis. Nucleosome mobility would be observed as nucleoprotein complexes migrating away from the diagonal, illustrated by the arrowheads. The asterisk indicates complexes of HMG-D with naked DNA. (B) The influence of HMG-D, histone H1/H5 and HMGB1 on nucleosome mobility. The assay was conducted as described above, with 50 fmol of nucleosomes reconstituted on the sea urchin 5S positioning sequence. Arrowheads indicate nucleosomes that have moved away from the diagonal and hence are mobile. Unlike H1/H5 and HMGB1, HMG-D does not restrict the intrinsic mobility of nucleosomes.

HMG-D does not inhibit the intrinsic mobility of nucleosomes

To test whether the lack of mobility of the 601.2 nucleosome in the presence of HMG-D was determined by the properties of the nucleosome or the protein we assayed the effect of HMG-D and histone H1/H5 on the mobility of nucleosomes reconstituted on the 207 bp sea urchin 5S rDNA positioning sequence, using HMGB1 as a control. On this fragment nucleosomes can occupy up to three translational positions and at high temperatures can move and reach equilibrium, with the majority of nucleosomes in the most energetically favourable position. Nucleosomes which migrate have a different mobility in the second dimension to that in the first and therefore are no longer located on the diagonal mobility (arrowheads in Fig. 2B). The migration of protein–DNA complexes is also observed (asterisk in Fig. 2). We confirmed that this nucleosome is intrinsically mobile and found that unlike HMGB1 and histone H1/H5, HMG-D does not inhibit mobility. This is evident from the appearance of nucleosomes with a higher mobility in the second dimension of electrophoresis. The migration of complexes of HMG-D and naked DNA was also altered, suggesting that HMG-D binding is transient.

H1 binding produces opposite effect to HMG-D

Along with HMGB proteins, linker histones H1, H5 and further variants are the major proteins bound to linker DNA. HMG-D is able to compete off H1 bound to chromatin in vitro (30). Early in Drosophila development the opposite is thought to occur (29). Furthermore, there is evidence that the linker histones bind to both the exiting and entering linker DNA (12). We were therefore curious to know what changes H1 would have on accessibility of DNA on reconstituted chromatosomes.

We used a mixture of native purified histone H1 and H5 from chicken erythrocytes. We recognize that this is not a homogeneous sample, with both H1a and H1b present, as well as a variety of post-translational modifications. H1 binding and digests were initially conducted under identical conditions to the HMG-D experiments, which resulted in problems with aggregation at stoichiometric binding concentrations, due to the presence of 2 mM MgCl2 in the binding buffer. To solve this problem we incubated nucleosomes with sub-stoichiometric concentrations of H1. Nucleosomes (30–50 fmol) were incubated with 20 nM H1/H5. As also observed with HMG-D, changes in rates of digestion are observed at protein concentrations well below full nucleosome occupancy.

Histone H1/H5 binding resulted in decreased accessibility at the majority of sites, with the exception of the MseI and BamHI sites (Fig. 1C). This pattern of accessibility is the opposite of that observed with HMG-D, especially at the PstI end of the nucleosome. Interestingly, we note that there is decreased accessibility at the sites near both the exit and entry points of the nucleosome. We observe, as with HMG-D, local changes to accessibility rather than an overall decrease in the rate of digestion at all sites.

DISCUSSION

The main conclusion of this paper is that HMG-D induces distinct changes in DNA accessibility on mononucleosomes. These changes involve increases at sites at the dyad and one end of the nucleosome and decreases in accessibility at all other sites examined. The pattern of accessibility suggests that HMG-D causes local changes in DNA binding rather than an increase or decrease in accessibility extending from one end of nucleosomal DNA, as would be predicted by the transient unwrapping model of Widom and colleagues.

We have verified that these changes are not due to sliding of nucleosomes upon binding. Nucleosomes reconstituted on the 601.2 positioning sequence remain at a single translational position at high temperatures. DNase I and hydroxyl radical footprinting also confirm that the pattern of accessibility is not due to sliding, as the dyad position remains the same in the presence or absence of HMG-D. This exceptional stability of nucleosomes containing the 601.2 positioning sequence may also account for the low rates of digestion, and thereby exposure of the different restriction sites. Indeed, the equilibrium constants for site exposure on the more mobile sea urchin 5S sequence are between one to two orders of magnitude greater than values for the 601.2 sequence (2). We would also expect the 601.2 nucleosome to be more stable to dissociation under the conditions of the restriction enzyme assay than other nucleosomes containing lower affinity binding sites (41).

Previous attempts at mapping H1 and HMGB1 binding on mononucleosomes have not revealed any changes in DNase I digestion patterns on the Xenopus 5S positioning sequence (31), although sites of protection in the linker between dinucleosomes was seen upon H1 binding (32). Bonaldi et al. (17) detected changes on mononucleosomes reconstituted on a fragment of the mouse rDNA promoter in the presence of HMGB1 (17). However, these nucleosomes occupy several translational positions on this sequence, making it difficult to locate precisely the sites of the observed changes in cleavage patterns. The restriction enzyme accessibility assay thus provides the first evidence of changes on nucleosomal DNA for HMG-D and H1 bound to a singly positioned nucleosome.

The formation of a spatial domain of accessibility encompassing the dyad and end of the nucleosome is in agreement with a proposed mechanism for HMGB proteins in remodelling (18). It has been suggested that HMGB proteins would bind to the edge of nucleosomes and bend DNA, creating a stabilized loop, which can be propagated by remodellers such as ACF and CHRAC (17).

A yeast HMGB protein, Nhp6, has recently been shown to increase the accessibility of certain internal sites to DNase I on mononucleosomes formed on the Lytechinus 5S rRNA gene (22). These experiments differ in major respects from ours. At least 10-fold higher protein:nucleosome ratios were required for this effect of Nhp6. The authors also argue that exposure of the sites requires the binding of multiple Nhp6 proteins. Similar results have been reported on the binding of multiple copies of GATA-1 to nucleosomes (8). The pattern of accessibility seen with HMG-D occurs at much lower protein:nucleosome ratios and is unlikely to be the result of binding by multiple proteins. Further, Nhp6 lacks the acidic tail that is required for the increase in accessibility induced by HMG-D. It is therefore possible that the mechanisms responsible for the changes in nucleosome structure observed in the presence of Nhp6 or HMG-D are distinct.

The creation of a domain of exposed DNA could also facilitate the binding of transcription factors to sites occluded by the nucleosome, thereby promoting the recruitment of higher order complexes. Bonaldi et al. found that a HMGB1 mutant lacking the C-terminal tail had a higher affinity for nucleosomes and inhibited sliding by ACF. They attribute this to the lower on/off rate of the mutant (42). Our results show that the C-terminal tail of HMG-D is necessary to produce the pattern of accessibility seen with the full-length protein. We can speculate that perhaps the negative residues in the tail are required to maintain the structure of the DNA within a topological domain, by binding to exposed histone residues (18). A combination of high affinity binding and the inability to stabilise the domain would both be contributing factors for the mutant’s ability to inhibit remodelling by ACF or CHRAC. Further studies are needed to establish whether the HMG-D tail contacts core histones.

In addition, Bonaldi et al. (17) observed that HMGB1 lacking the C-terminal tail has increased activity in transactivation assays. However Yoshida and colleagues found that the same mutant causes repression of transcription of a reporter, with the presence of the acidic tail required for activation of transcription (43,44). We observe a decrease in or inhibition of accessibility with the tail mutant. Taken together, the observations of decreased DNA accessibility, inhibition of remodelling and repression of transcription provide more evidence that the tail is important for functions relating to increased access to chromatin and transcriptional activation.

Histone H1 binding to mononucleosomes and nucleosomal arrays has been shown to inhibit chromatin remodelling by SWI/SNF (26), ACF and Mi-2 complexes (27). Association of histone H1 to chromatin also promotes higher order folding and restricts transcription factor accessibility (23–25). The restriction assay shows that nucleosomes incorporating H1/H5 become less accessible to digestion at most sites, with the exception of an increased accessibility at the MseI and BamHI sites. Rather than a global decrease in accessibility, varying degrees of inhibition are seen at different sites. Decreases at the end and centre of nucleosomal DNA can be explained by steric occlusion by the primary binding of H1/H5 on one face of the nucleosome (10,12), but this does not explain the decrease in accessibility on the opposite face. Possibly this is attributable to a structural change in the wrapped DNA. Overall the data indicate that H1/H5 binding, like HMG-D, causes local changes in DNA accessibility. Importantly, the DNA at the ends of the nucleosome is less accessible in the presence of H1/H5, consistent with the electron microscopy studies of Hamiche et al. (12).

The implications

Previous studies have shown that H1 and HMGB1, when assembled onto chromatin, promote the formation of regularly spaced nucleosomal arrays. Binding of both proteins has also been shown to inhibit the intrinsic mobility of nucleosomes. Our results confirm this property, but show that HMG-D does not inhibit intrinsic mobility under our assay conditions. This suggests that structures found in HMGB1 but lacking in HMG-D contribute to this behaviour.

Ner et al. (29) have shown that HMG-D is associated with early embryonic chromatin, and is diluted as histone H1 is produced during later stages. It was subsequently shown that HMG-D competes with H1 for binding to chromatin in vitro (29,30). The binding of HMG-D during early development may lead to a chromatin structure that facilitates rapid DNA replication cycles, and so requires nucleosome mobility, while H1 binding forms transcriptionally regulated chromatin. HMGB proteins may perform additional roles depending on the context. In the context of chromatin remodelling HMGB1 has been shown to increase both the rate of nucleosome sliding by the CHRAC complex and the affinity of recombinant ACF for nucleosomes (17). As suggested by the authors, HMGB1 binding could generate a loop of DNA or aid in its formation by ACF. Our results demonstrate the formation of a region of increased accessibility at the site where ACF binding might occur. One consequence of increased accessibility even on one side of the dyad would be to loosen one of the strongest histone–DNA contacts that occur in this region (8). In contrast, histone H1 has an inhibitory effect on remodelling by CHRAC and other remodelling complexes (27). We observe that nucleosome accessibility is decreased at most sites upon H1/H5 binding.

Evidence that H1 restricts the mobility of nucleosomes and DNA accessibility while HMG-D has the opposite effect supports the hypothesis of their competition in vivo. Histone H1 binding would ‘lock’ nucleosomes in position on chromatin, restricting transcription factor access and preventing remodelling. HMG-D binding to nucleosomes would result in increased mobility, facilitation of remodelling and increased transactivation through transcription factor binding. Chromatin accessibility would therefore be dependent on association with HMG-D, and active remodelling at nucleosomes that had been ‘primed’ by HMG-D.

In the context of transcription there would be a competition between H1 and HMGB proteins. H1 and HMGB1 both have very high on/off rates on chromatin and their binding affinity is regulated through post-translational modification. Competition between these proteins would result in the opening and closing of accessible domains on specific nucleosomes, while maintaining overall chromatin structure.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at NAR Online.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Philip Robinson and Jean Thomas for providing reagents, Jonathan Widom and Peggy Lowary for the gift of the plasmid pGEM-3Z-601.2 and Sari Pennings for the gift of the plasmid p5S207-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Luger K., Mader,A.W., Richmond,R.K., Sargent,D.F. and Richmond,T.J. (1997) Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature, 389, 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson J.D. and Widom,J. (2000) Sequence and position-dependence of the equilibrium accessibility of nucleosomal DNA target sites. J. Mol. Biol., 296, 979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson J.D., Thåström,A. and Widom,J. (2002) Spontaneous access of proteins to buried nucleosomal DNA target sites occurs via a mechanism that is distinct from nucleosome translocation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 22, 7147–7157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller J.A. and Widom,J. (2003) Collaborative competition mechanism for gene activation in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol., 23, 1623–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polach K.J. and Widom,J. (1995) Mechanism of protein access to specific DNA sequences in chromatin: a dynamic equilibrium model for gene regulation. J. Mol. Biol., 254, 130–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angelov D., Molla,A., Perche,P.Y., Hans,F., Côté,J., Khochbin,S., Bouvet,P. and Dimitrov,S. (2003) The histone variant macroH2A interferes with transcription factor binding and SWI/SNF nucleosome remodeling. Mol. Cell, 11, 1033–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhodes D. (1985) Structural analysis of a triple complex between the histone octamer, a Xenopus gene for 5S RNA and transcription factor IIIA. EMBO J., 4, 3473–3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyes J., Omichinski,J., Clark,D., Pikaart,M. and Felsenfeld,G. (1998) Perturbation of nucleosome structure by the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1. J. Mol. Biol., 279, 529–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An W., van Holde,K. and Zlatanova,J. (1998) The non-histone chromatin protein HMG1 protects linker DNA on the side opposite to that protected by linker histones. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 26289–26291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Y.B., Gerchman,S.E., Ramakrishnan,V., Travers,A. and Muyldermans,S. (1998) Position and orientation of the globular domain of linker histone H5 on the nucleosome. Nature, 395, 402–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas J.O. (1999) Histone H1: location and role. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 11, 312–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamiche A., Schultz,P., Ramakrishnan,V., Oudet,P. and Prunell,A. (1996) Linker histone-dependent DNA structure in linear mononucleosomes. J. Mol. Biol., 257, 30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas J.O. and Travers,A.A. (2001) HMG1 and 2 and related ‘architectural’ DNA-binding proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci., 26, 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang W., Chi,T., Xue,Y., Zhou,S., Kuo,A. and Crabtree,G.R. (1998) Architectural DNA binding by a high-mobility-group/kinesin-like subunit in mammalian SWI/SNF-related complexes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 492–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papoulas O., Daubresse,G., Armstrong,J.A., Jin,J., Scott,M.P. and Tamkun,J.W. (2001) The HMG-domain protein BAP111 is important for the function of the BRM chromatin-remodeling complex in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 5728–5733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orphanides G., Wu,W.H., Lane,W.S., Hampsey,M. and Reinberg,D. (1999) The chromatin-specific transcription elongation factor FACT comprises human SPT16 and SSRP1 proteins. Nature, 400, 284–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonaldi T., Längst,G., Strohner,R., Becker,P.B. and Bianchi,M.E. (2002) The DNA chaperone HMGB1 facilitates ACF/CHRAC-dependent nucleosome sliding. EMBO J., 21, 6865–6873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Travers A.A. (2003) Priming the nucleosome: a role for HMGB proteins? EMBO Rep., 4, 131–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu Y., Eriksson,P., Bhoite,L.T. and Stillman,D.J. (2003) Regulation of TATA-binding protein binding by the SAGA complex and the Nhp6 high-mobility group protein. Mol. Cell. Biol., 23, 1910–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szerlong H., Saha,A. and Cairns,B.R. (2003) The nuclear actin-related proteins Arp7 and Arp9: a dimeric module that cooperates with architectural proteins for chromatin remodeling. EMBO J., 22, 3175–3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Formosa T., Eriksson,P., Wittmeyer,J., Ginn,J., Yu,Y. and Stillman,D.J. (2001) Spt16-Pob3 and the HMG protein Nhp6 combine to form the nucleosome-binding factor SPN. EMBO J., 20, 3506–3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruone S., Rhoades,A.R. and Formosa,T. (2003) Multiple Nhp6 molecules are required to recruit Spt16-Pob3 to form yFACT complexes and to reorganize nucleosomes. J. Biol. Chem., 10.1074/jbc.M307291200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sera T. and Wolffe,A.P. (1998) Role of histone H1 as an architectural determinant of chromatin structure and as a specific repressor of transcription on Xenopus oocyte 5S rRNA genes. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 3668–3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carruthers L.M., Bednar,J., Woodcock,C.L. and Hansen,J.C. (1998) Linker histones stabilize the intrinsic salt-dependent folding of nucleosomal arrays: mechanistic ramifications for higher-order chromatin folding. Biochemistry, 37, 14776–14787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juan L.J., Utley,R.T., Vignali,M., Bohm,L. and Workman,J.L. (1997) H1-mediated repression of transcription factor binding to a stably positioned nucleosome. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 3635–3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill D.A. and Imbalzano,A.N. (2000) Human SWI/SNF nucleosome remodeling activity is partially inhibited by linker histone H1. Biochemistry, 39, 11649–11656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horn P.J., Carruthers,L.M., Logie,C., Hill,D.A., Solomon,M.J., Wade,P.A., Imbalzano,A.N., Hansen,J.C. and Peterson,C.L. (2002) Phosphorylation of linker histones regulates ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling enzymes. Nature Struct. Biol., 9, 263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dimitrov S., Almouzni,G., Dasso,M. and Wolffe,A.P. (1993) Chromatin transitions during early Xenopus embryogenesis: changes in histone H4 acetylation and in linker histone type. Dev. Biol., 160, 214–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ner S.S. and Travers,A.A. (1994) HMG-D, the Drosophila melanogaster homologue of HMG 1 protein is associated with early embryonic chromatin in the absence of histone H1. EMBO J., 13, 1817–1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ner S.S., Blank,T., Perez-Paralle,M.L., Grigliatti,T.A., Becker,P.B. and Travers,A.A. (2001) HMG-D and histone H1 interplay during chromatin assembly and early embryogenesis. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 37569–37576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nightingale K., Dimitrov,S., Reeves,R. and Wolffe,A.P. (1996) Evidence for a shared structural role for HMG1 and linker histones B4 and H1 in organizing chromatin. EMBO J., 15, 548–561. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ura K., Nightingale,K. and Wolffe,A.P. (1996) Differential association of HMG1 and linker histones B4 and H1 with dinucleosomal DNA: structural transitions and transcriptional repression. EMBO J., 15, 4959–4969. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pennings S., Meersseman,G. and Bradbury,E.M. (1994) Linker histones H1 and H5 prevent the mobility of positioned nucleosomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 10275–10279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Payet D. and Travers,A. (1997) The acidic tail of the high mobility group protein HMG-D modulates the structural selectivity of DNA binding. J. Mol. Biol., 266, 66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones D.N.M., Searles,M.A, Shaw,G.L., Churchill,M.E.A., Ner,S.S, Keeler,J., Travers,A.A and Neuhaus,D. (1994) The solution structure and dynamics of the DNA-binding domain of HMG-D from Drosophila melanogaster. Structure, 2, 609–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas J.O. (1998) Isolation and fractionation of chromatin and linker histones. In Gould,H.G. (ed.), Chromatin: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tatchell K. and Van Holde,K.E. (1977) Reconstitution of chromatin core particles. Biochemistry, 16, 5295–5303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Webb M., Payet,D., Lee,K.B., Travers,A.A. and Thomas,J.O. (2001) Structural requirements for cooperative binding of HMG1 to DNA minicircles. J. Mol. Biol., 309, 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meersseman G., Pennings,S. and Bradbury,E.M. (1992) Mobile nucleosomes—a general behavior. EMBO J., 11, 2951–2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ura K., Hayes,J.J. and Wolffe,A.P. (1995) A positive role for nucleosome mobility in the transcriptional activity of chromatin templates: restriction by linker histones. EMBO J., 14, 3752–3765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gottesfeld J.M. and Luger,K. (2001) Energetics and affinity of the histone octamer for defined DNA sequences. Biochemistry, 40, 10927–10933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bianchi M.E. and Beltrame,M. (2000) Upwardly mobile proteins. Workshop: the role of HMG proteins in chromatin structure, gene expression and neoplasia. EMBO Rep., 1, 109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aizawa S., Nishino,H., Saito,K., Kimura,K., Shirakawa,H. and Yoshida,M. (1994) Stimulation of transcription in cultured cells by high mobility group protein 1: essential role of the acidic carboxyl-terminal region. Biochemistry, 33, 14690–14695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogawa Y., Aizawa,S., Shirakawa,H. and Yoshida,M. (1995) Stimulation of transcription accompanying relaxation of chromatin structure in cells overexpressing high mobility group 1 protein. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 9272–9280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.